The Changing Face of Emma

Online ExhibitEmma Avenue has been the heart of Springdale’s downtown district for over 130 years. Springdale’s first mayor, Joseph Holcomb, named the thoroughfare after his stepdaughter, Emma Dupree Deaver.

Like many of Northwest Arkansas’ main streets, at one time Emma was all things to all people. It was a destination, both for citizens and rural folk who came to town to shop, conduct business, and socialize. It was an agricultural hub, where farmers and businessmen sold and shipped huge quantities of produce and poultry. And it was a gathering place, uniting the community through parades, festivals, and events.

As Springdale grew, new roads and commercial districts were developed. Retailers followed the traffic, moving their businesses away from Emma. Agricultural businesses left as well when the produce industry declined and poultry companies expanded to larger operations outside the town’s core. Emma’s prosperity and importance faded. Many attempts were made to revitalize downtown, with limited success. But today Emma is once again becoming a destination and community center with the arrival of new merchants, recreational activities, and diverse events. Emma has been reborn.

Emma Avenue has been the heart of Springdale’s downtown district for over 130 years. Springdale’s first mayor, Joseph Holcomb, named the thoroughfare after his stepdaughter, Emma Dupree Deaver.

Like many of Northwest Arkansas’ main streets, at one time Emma was all things to all people. It was a destination, both for citizens and rural folk who came to town to shop, conduct business, and socialize. It was an agricultural hub, where farmers and businessmen sold and shipped huge quantities of produce and poultry. And it was a gathering place, uniting the community through parades, festivals, and events.

As Springdale grew, new roads and commercial districts were developed. Retailers followed the traffic, moving their businesses away from Emma. Agricultural businesses left as well when the produce industry declined and poultry companies expanded to larger operations outside the town’s core. Emma’s prosperity and importance faded. Many attempts were made to revitalize downtown, with limited success. But today Emma is once again becoming a destination and community center with the arrival of new merchants, recreational activities, and diverse events. Emma has been reborn.

Emma Avenue through the Decades

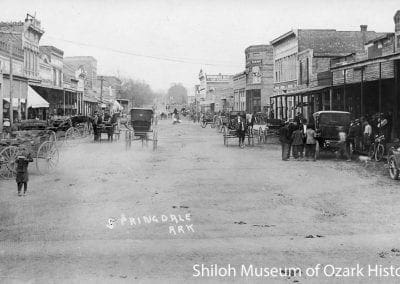

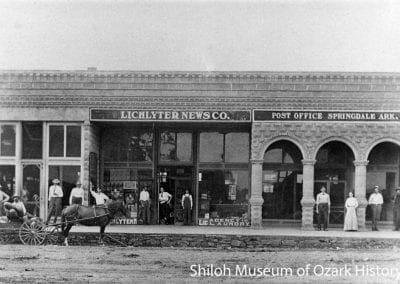

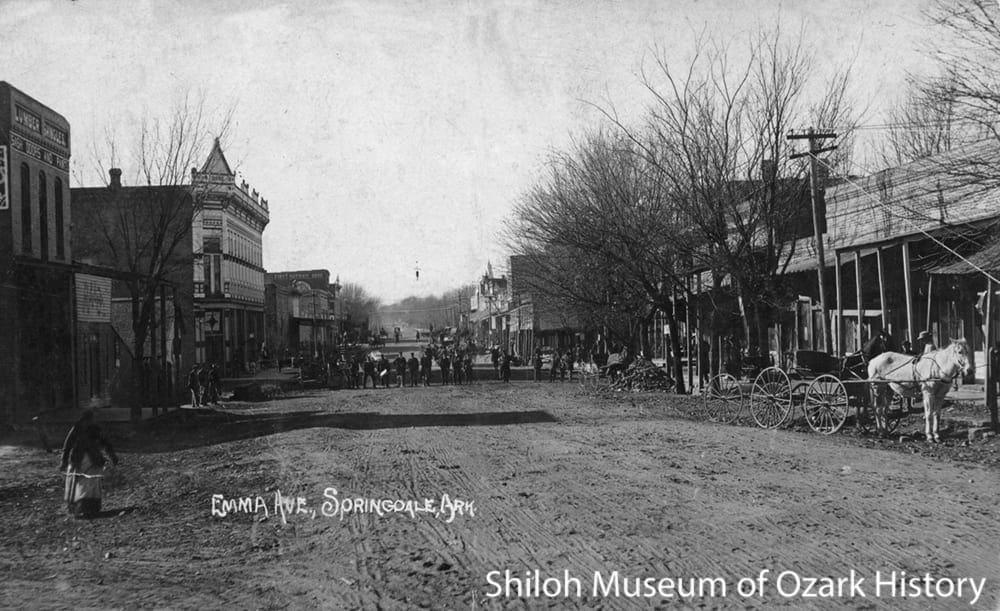

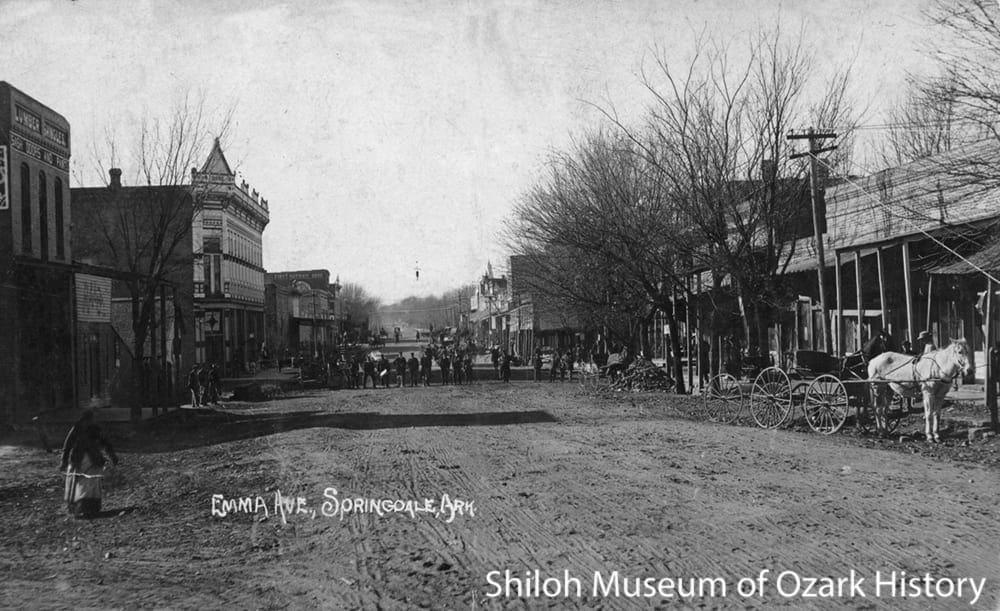

Looking east on Emma Avenue, near the intersection of Main and Emma, early 1900s. Shiloh Museum Purchase (S-92-136-13)

Beginnings

Looking west on Emma Avenue, from near the railroad tracks, early 1900s. D. D. Deaver Collection (S-78-18)

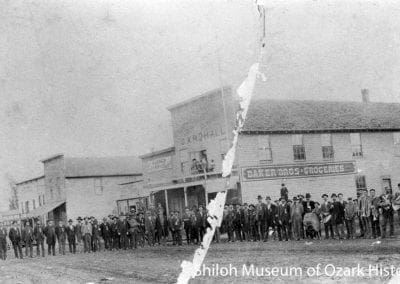

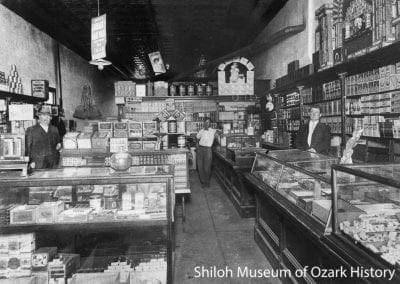

When Springdale was incorporated in 1878, the land where the Shiloh Museum now stands was the center of town. It was surrounded by homes, businesses, churches, and farms. In the early 1880s Mayor Jo Holcomb encouraged merchants to move to his property a few blocks southeast by offering land at low or no cost. Why? Because that’s where the St. Louis & San Francisco (Frisco) Railroad built a depot in 1881 as it steamed its way through Northwest Arkansas. A commercial district formed on the new street named for Holcomb’s stepdaughter, Emma Dupree Deaver.

Some of the earliest buildings were made of wood, making them quick to build but also quick to burn down. When fire wiped out a block of wood buildings near the depot, more permanent brick structures were built in their place. In 1897 the core of the business district was from Main Street east to the railroad tracks. Emma was home to produce companies, banks, livery stables, barbershops, apple evaporators, and hotels, along with stores which sold food, clothing, hardware, and household supplies.

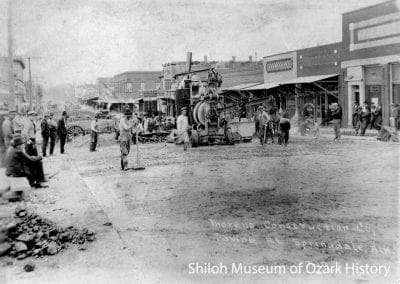

Spring Creek ran north through Emma, roughly along Spring Street. Flooding was a continual problem. Ditches and drains helped channel some of the water, but not all. A bridge of sorts was built over the creek to contain it, with structures built atop. But whenever there was a heavy rain, merchants reluctantly opened their doors to let the water flow through their buildings. Emma’s dirt roadbed turned into a muddy mess. The street was paved in 1925, making it popular both with merchants and roller skaters.

Beginnings

Looking west on Emma Avenue, from near the railroad tracks, early 1900s. D. D. Deaver Collection (S-78-18)

When Springdale was incorporated in 1878, the land where the Shiloh Museum now stands was the center of town. It was surrounded by homes, businesses, churches, and farms. In the early 1880s Mayor Jo Holcomb encouraged merchants to move to his property a few blocks southeast by offering land at low or no cost. Why? Because that’s where the St. Louis & San Francisco (Frisco) Railroad built a depot in 1881 as it steamed its way through Northwest Arkansas. A commercial district formed on the new street named for Holcomb’s stepdaughter, Emma Dupree Deaver.

Some of the earliest buildings were made of wood, making them quick to build but also quick to burn down. When fire wiped out a block of wood buildings near the depot, more permanent brick structures were built in their place. In 1897 the core of the business district was from Main Street east to the railroad tracks. Emma was home to produce companies, banks, livery stables, barbershops, apple evaporators, and hotels, along with stores which sold food, clothing, hardware, and household supplies.

Spring Creek ran north through Emma, roughly along Spring Street. Flooding was a continual problem. Ditches and drains helped channel some of the water, but not all. A bridge of sorts was built over the creek to contain it, with structures built atop. But whenever there was a heavy rain, merchants reluctantly opened their doors to let the water flow through their buildings. Emma’s dirt roadbed turned into a muddy mess. The street was paved in 1925, making it popular both with merchants and roller skaters.

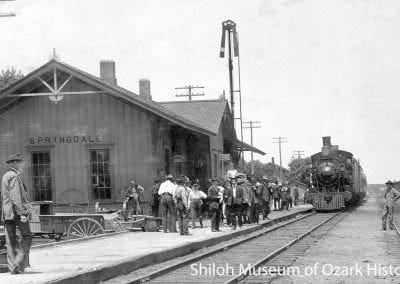

Frisco depot, circa 1910. This is the second depot, built in 1901. Speece and Aaron, photographers. Mildred Sisco Collection (S-78-49)

Grand Army of the Republic members and hall, early 1890s. These buildings burned down in 1901. Marion S. Warner Collection (S-92-157-68)

Concrete block building, circa 1910. Built to replace buildings lost to fire. Dr. Charles Sisco Collection (S-2003-2-1111)

Kimmons-Walker apple evaporator, circa 1910. Austin Cravens and W. Fay Atkisson Collection (S-82-97-4A)

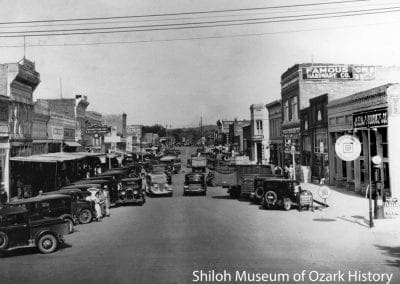

Growth

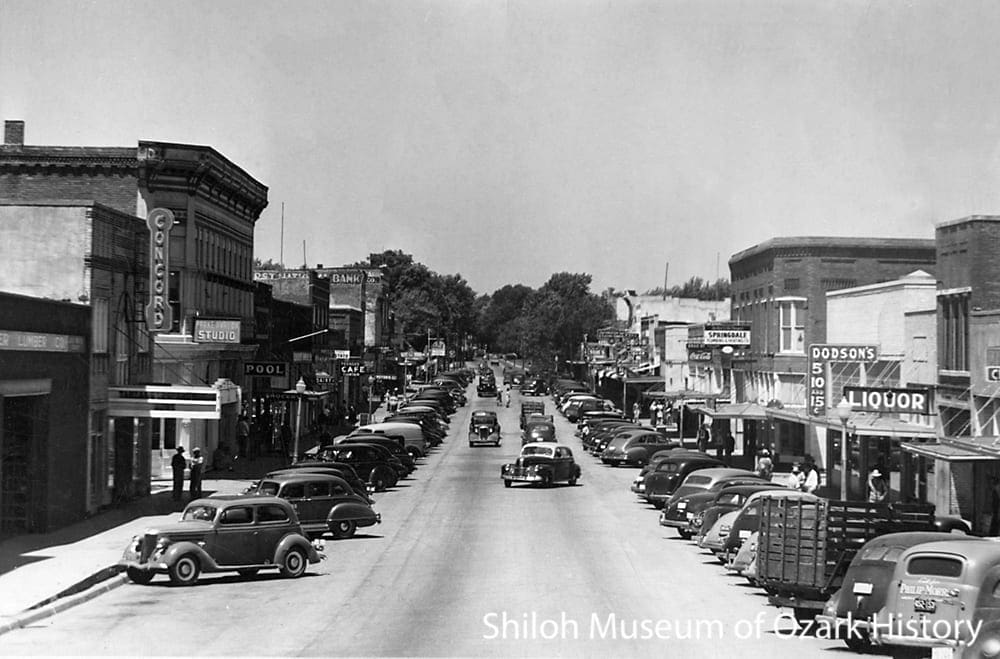

Back in its heyday Emma was a busy, thriving street. By the late 1800s Springdale’s main industry was agriculture, thanks to the railroad which gave farmers a chance to ship their produce beyond Northwest Arkansas. Thousands of railroad cars of apples, strawberries, grapes, and other produce were shipped from the depot on Emma. Each spring trucks filled the street as buyers came to examine, select, and purchase strawberries.

Beginning in the 1920s produce-businesses moved to the east side of the tracks. They were joined by poultry suppliers and growers in the 1930s and 1940s, among them Jeff Brown, C.L. George, and John Tyson. Further down the street Harvey Jones’ trucking company hauled such freight as lumber and fruit throughout the region. These men, who all got their start on Emma, turned their small companies into corporate giants, bringing wealth and prosperity to the area.

Growth

Back in its heyday Emma was a busy, thriving street. By the late 1800s Springdale’s main industry was agriculture, thanks to the railroad which gave farmers a chance to ship their produce beyond Northwest Arkansas. Thousands of railroad cars of apples, strawberries, grapes, and other produce were shipped from the depot on Emma. Each spring trucks filled the street as buyers came to examine, select, and purchase strawberries.

Beginning in the 1920s produce-businesses moved to the east side of the tracks. They were joined by poultry suppliers and growers in the 1930s and 1940s, among them Jeff Brown, C.L. George, and John Tyson. Further down the street Harvey Jones’ trucking company hauled such freight as lumber and fruit throughout the region. These men, who all got their start on Emma, turned their small companies into corporate giants, bringing wealth and prosperity to the area.

Strawberry market, late 1930s. Dr. J. Lawrence Charlton, photographer. Dr. J. Lawrence Charlton Collection (S-86-15-9)

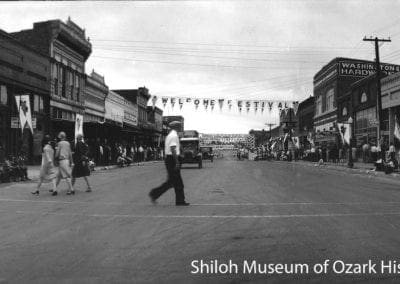

Community

Emma was the “town square” of Springdale, the place were high school students met for sodas, where hunters showed off their trophy bucks, and where crowds gathered to watch traveling medicine shows. Politicians like Governors Orval Faubus and Bill Clinton often visited the street to glad-hand voters and wave from parade cars. Springdale is famous for its parades. Early on, Fourth of July festivities honored Civil War veterans and welcomed back World War I soldiers and nurses. During the mid-1920s the Ozark Grape Festival parades celebrated the area’s grape industry.

The first official Rodeo of the Ozarks parade was held in 1946 and featured riding clubs, marching bands, and floats and cars decorated by local businesses. As the rodeo grew, so did community involvement. During Western Week merchants decorated their store windows with a rodeo theme. Folks caught not wearing western clothing on Emma were sometimes subject to a good-natured fine or a dunking in a large tub of water. The rodeo also sponsored an annual Christmas parade.

Community

Emma was the “town square” of Springdale, the place were high school students met for sodas, where hunters showed off their trophy bucks, and where crowds gathered to watch traveling medicine shows. Politicians like Governors Orval Faubus and Bill Clinton often visited the street to glad-hand voters and wave from parade cars. Springdale is famous for its parades. Early on, Fourth of July festivities honored Civil War veterans and welcomed back World War I soldiers and nurses. During the mid-1920s the Ozark Grape Festival parades celebrated the area’s grape industry.

The first official Rodeo of the Ozarks parade was held in 1946 and featured riding clubs, marching bands, and floats and cars decorated by local businesses. As the rodeo grew, so did community involvement. During Western Week merchants decorated their store windows with a rodeo theme. Folks caught not wearing western clothing on Emma were sometimes subject to a good-natured fine or a dunking in a large tub of water. The rodeo also sponsored an annual Christmas parade.

Downtown business owners Espen and Lois Walters with Gov. Orval Faubus (right), circa 1964. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-93-36-803)

Revitalization

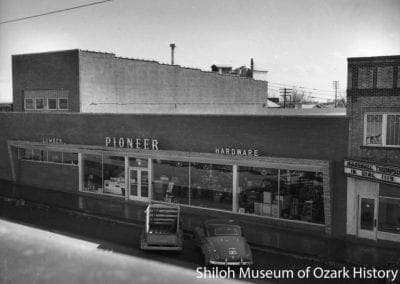

Over the years Emma’s buildings were updated to reflect a fresh, modern look. Old-fashioned tin ceilings were covered and stucco and metal siding hid old brick walls. Around 1950 Pioneer Lumber unified its odd mix of buildings into one storefront with plate-glass windows and a streamlined brick exterior. Later renovations have all but hidden the original 1895-era two-story building.

Floods changed the look of Emma too. On May 29, 1950, heavy rains caused Spring Creek to rise quickly. Water surged through downtown, washing debris towards the Meadow Street bridge. The debris jammed, causing the water to back up on Emma. Items began floating away, some through smashed plate-glass windows—chairs and a showcase at Penrod’s Café, boards at Pioneer Lumber, and the organ console at the Apollo Theater. The next day Wilson’s held what may have been Emma’s first sidewalk sale, selling flood-damaged clothing to buyers eager for a discount.

Although Springdale leaders wanted a better drainage system, they didn’t have the funds. That began to change in the 1960s when the city underwent urban renewal, a federal program meant to revitalize the nation’s downtowns. The multimillion-dollar project addressed several Emma-related issues including increased parking for shoppers and employees, the channelization of Spring Creek with concrete culverts to eliminate flooding, and the demolition or modernization of several historic buildings.

New structures went up in some of the holes left behind, including San Jose Manor, a business mall built by businessmen Sandy Boone and Joe Steele, and Shiloh Square, a community pavilion built over a Spring Creek drainage culvert. Events such as fried-chicken dinners, arts and crafts shows, and high school pep rallies were held there. Years later the space was fenced off because of damage done by skateboarders and graffiti artists.

Other attempts to revitalize Springdale’s downtown included redevelopment studies, landscaping, parking meter removal, and changes to on-street parking spaces.

Revitalization

Over the years Emma’s buildings were updated to reflect a fresh, modern look. Old-fashioned tin ceilings were covered and stucco and metal siding hid old brick walls. Around 1950 Pioneer Lumber unified its odd mix of buildings into one storefront with plate-glass windows and a streamlined brick exterior. Later renovations have all but hidden the original 1895-era two-story building.

Floods changed the look of Emma too. On May 29, 1950, heavy rains caused Spring Creek to rise quickly. Water surged through downtown, washing debris towards the Meadow Street bridge. The debris jammed, causing the water to back up on Emma. Items began floating away, some through smashed plate-glass windows—chairs and a showcase at Penrod’s Café, boards at Pioneer Lumber, and the organ console at the Apollo Theater. The next day Wilson’s held what may have been Emma’s first sidewalk sale, selling flood-damaged clothing to buyers eager for a discount.

Although Springdale leaders wanted a better drainage system, they didn’t have the funds. That began to change in the 1960s when the city underwent urban renewal, a federal program meant to revitalize the nation’s downtowns. The multimillion-dollar project addressed several Emma-related issues including increased parking for shoppers and employees, the channelization of Spring Creek with concrete culverts to eliminate flooding, and the demolition or modernization of several historic buildings.

New structures went up in some of the holes left behind, including San Jose Manor, a business mall built by businessmen Sandy Boone and Joe Steele, and Shiloh Square, a community pavilion built over a Spring Creek drainage culvert. Events such as fried-chicken dinners, arts and crafts shows, and high school pep rallies were held there. Years later the space was fenced off because of damage done by skateboarders and graffiti artists.

Other attempts to revitalize Springdale’s downtown included redevelopment studies, landscaping, parking meter removal, and changes to on-street parking spaces.

Pioneer Lumber Co. building, 1950. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-2053)

Pioneer Lumber Co. building, 1979. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-113-139)

Pioneer Lumber Co. building, 1993. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 8-2-1993)

Flooding on Emma Avenue, looking west from Shiloh Street, June 1965. Jim Morriss, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 6/1965 #2)

Tearing down the First State Bank vault, part of urban renewal, February 16, 1971. Jim Morriss, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 2-16-1971)

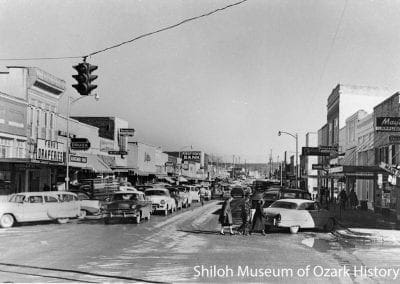

Decline

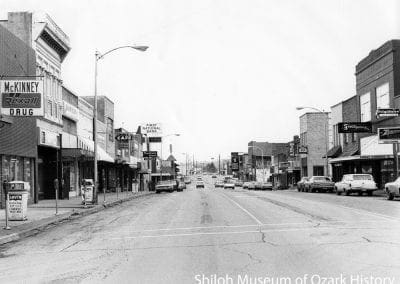

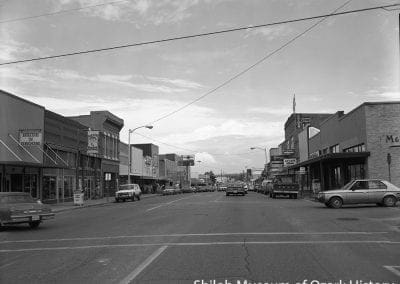

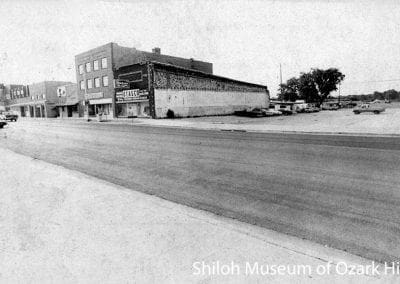

Looking east, February 1, 1973. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-13-94A)

Emma’s landscape and energy was changing. In 1965 the Frisco ended passenger service in Northwest Arkansas, reducing activity at the depot. During urban renewal buildings were torn down and replaced with parking lots. Some thought the changes helpful, others didn’t. While Emma still had merchants, shoppers were drifting away. Highway 71’s high volume of traffic beckoned as a place for downtown store owners to relocate. As the years passed, buildings on Emma emptied and longtime mainstays closed their doors. The Springdale News, Tyson Foods, and Famous Hardware buildings became a farm-supply store, a grocery, and an antique store, respectively.

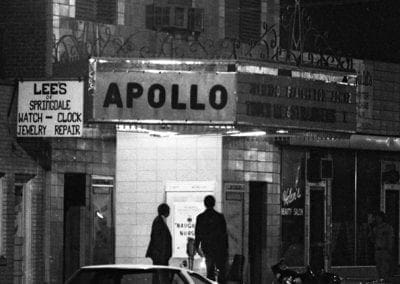

When Bill Sonneman opened the Apollo Theater in 1949 it was a showplace with velvet seats, a pipe organ, and a handsome marble statue of the Greek god Apollo. In the early 1970s the theater’s new owners hoped to turn a profit by showing X-rated movies. After opposition by citizens and the Springdale City Council, authorities took action in 1975. Police raided the theater and seized the film, Touch Me. The Apollo closed for several years before reopening as a music venue. By 2002 the building was once again shuttered and later condemned.

Decline

Looking east, February 1, 1973. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-13-94A)

Emma’s landscape and energy was changing. In 1965 the Frisco ended passenger service in Northwest Arkansas, reducing activity at the depot. During urban renewal buildings were torn down and replaced with parking lots. Some thought the changes helpful, others didn’t. While Emma still had merchants, shoppers were drifting away. Highway 71’s high volume of traffic beckoned as a place for downtown store owners to relocate. As the years passed, buildings on Emma emptied and longtime mainstays closed their doors. The Springdale News, Tyson Foods, and Famous Hardware buildings became a farm-supply store, a grocery, and an antique store, respectively.

When Bill Sonneman opened the Apollo Theater in 1949 it was a showplace with velvet seats, a pipe organ, and a handsome marble statue of the Greek god Apollo. In the early 1970s the theater’s new owners hoped to turn a profit by showing X-rated movies. After opposition by citizens and the Springdale City Council, authorities took action in 1975. Police raided the theater and seized the film, Touch Me. The Apollo closed for several years before reopening as a music venue. By 2002 the building was once again shuttered and later condemned.

Highway 71 in 1965, looking north from Sunset Avenue, April 9, 1965. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-24-68)

Urban renewal, looking southeast from the corner of Emma and Spring at a new parking lot created by Urban Renewal, May 30, 1974. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-24-47)

Rebirth

Outdoor street dinner sponsored by Downtown Springdale Alliance, May 21, 2016. Courtesy Kim Christie, photographer.

Today Springdale is involved in a different kind of urban renewal, one which is drawing people and businesses back downtown. Perhaps the event that triggered this latest round of activity was the coming of the Razorback Greenway, an extensive system of trails throughout Northwest Arkansas. The Greenway cuts through downtown Emma next to a remodeled Shiloh Square and newly built Walter Turnbow Park, which exposes the long-buried waters of Spring Creek. What was once a problem is now an asset.

A land rush of sorts is occurring on Emma. Merchants are refurbishing buildings and opening new businesses. The interest in craft spirits has led to brew pubs, bars, and an apple cidery. The old Apollo Theater has been renovated and is now an event space. And Tyson Foods returned to its original home in what is now the Springdale Poultry Industry Historic District. An increasingly diverse population is putting its own stamp on the street with Latino-owned businesses and Marshallese-community events.

Emma’s recent improvements are due to the efforts and investments of many. City- and citizen-based initiatives are developing building codes, promoting Emma on social media, and hosting events like outdoor street dinners and the Hogeye Marathon. Large players like Tyson Foods and the family of Walmart founder Sam Walton have purchased buildings for development. They, along with the Care Foundation and the Springdale Chamber of Commerce, have donated money towards the construction of the Greenway and Turnbow Park. Tyson’s has also given $1 million to the Downtown Springdale Alliance, a nonprofit group working to rejuvenate downtown.

While old-timers will find a different street from days gone by, they’re sure to appreciate seeing the old buildings brought back to life and people once again enjoying Emma Avenue.

Rebirth

Outdoor street dinner sponsored by Downtown Springdale Alliance, May 21, 2016. Courtesy Kim Christie, photographer.

Today Springdale is involved in a different kind of urban renewal, one which is drawing people and businesses back downtown. Perhaps the event that triggered this latest round of activity was the coming of the Razorback Greenway, an extensive system of trails throughout Northwest Arkansas. The Greenway cuts through downtown Emma next to a remodeled Shiloh Square and newly built Walter Turnbow Park, which exposes the long-buried waters of Spring Creek. What was once a problem is now an asset.

A land rush of sorts is occurring on Emma. Merchants are refurbishing buildings and opening new businesses. The interest in craft spirits has led to brew pubs, bars, and an apple cidery. The old Apollo Theater is undergoing renovation for future use as an event space. And Tyson Foods will return to its original home in what is now the Springdale Poultry Industry Historic District. An increasingly diverse population is putting its own stamp on the street with Latino-owned businesses and Marshallese-community events.

Emma’s recent improvements are due to the efforts and investments of many. City- and citizen-based initiatives are developing building codes, promoting Emma on social media, and hosting events like outdoor street dinners and the Hogeye Marathon. Large players like Tyson Foods and the family of Walmart founder Sam Walton have purchased buildings for development. They, along with the Care Foundation and the Springdale Chamber of Commerce, have donated money towards the construction of the Greenway and Turnbow Park. Tyson’s has also given $1 million to the Downtown Springdale Alliance, a nonprofit group working to rejuvenate downtown.

While old-timers will find a different street from days gone by, they’re sure to appreciate seeing the old buildings brought back to life and people once again enjoying Emma Avenue.

Tyson’s Feed and Hatchery, 1957. From left: Ralph Blythe, Roy Grimsley, Don Tyson, and Hiron “Poke” Knight. Tyson Foods Collection (S-86-109-78)

Jemenei Day celebration, also known as Marshall Islands Constitution Day, Shiloh Square, May 27, 2016. Consulate General Carmen Chong-Gum is dressed in red.