Scenes of Boone County

Online ExhibitThe area which is now Boone County was once home to Native Americans like the Osage. Spanish and French explorers later came through, followed by settlers from Tennessee, Kentucky, and other southern states. The land was heavily forested and hilly, so new arrivals came by river until roads could be built for wagons. In December 1818 explorer Henry R. Schoolcraft stopped at Sugarloaf Prairie near Lead Hill and said this of the inhabitants:

They raise corn for bread, and for feeding their horses previous to the commencement of long journeys in the woods, but none for exportation. No cabbages, beets, onions, potatoes, turnips, or other garden vegetables are raised. Gardens are unknown. Corn and other wild meats, chiefly bear’s meat, are the staple articles of food. In manners, morals, customs, dress, contempt for labor and hospitality, the state of society is not essentially different from that which exists among the savages.

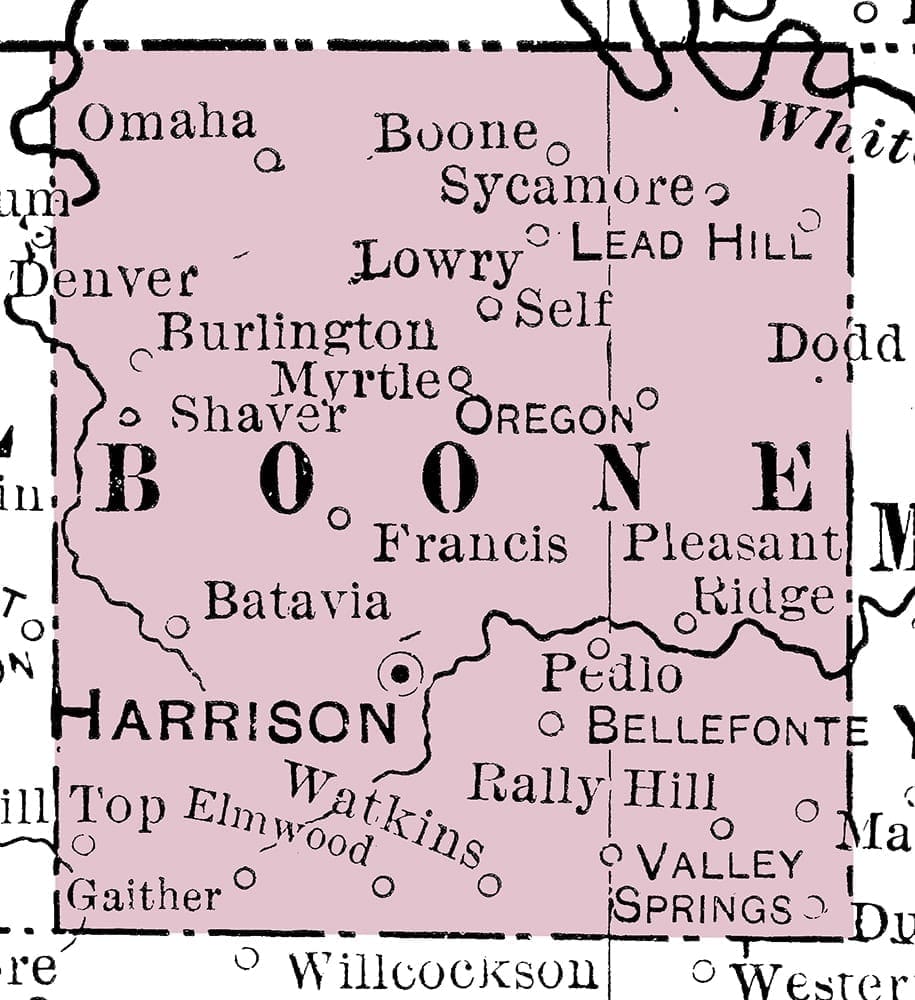

An east-west military road, also known as the Washington Road, was built in the days when the area was part of a much larger Carroll County. Boone County was created in 1869 from a large chunk of Carroll County; a few years later a small portion of Marion County was added. The county wasn’t named after Daniel Boone, as some have claimed. Rather, its beautiful land was said to be a boon (a gift) to its settlers.

Farmers found prairies and other land suitable for grazing livestock and planting such crops as cotton, corn, and fruit. Zinc and lead were mined and forests were heavily logged for such products as railroad ties, lumber, barrel staves, and tool handles. The coming of the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad in 1901 meant that more of Boone County’s products could be shipped to market. In 1905 the Harrison Times wrote:

“There is stamped upon our people the signet of enterprise and broad-gauged public spirit; we are moving steadily onward in wealth, material prosperity and advances of culture with the courage of self-assertion. . . . Enterprise is planning new forms; labor a new impetus; brain and brawn are at work and we are moving steadily onward and upward in progress and advancement.”

Some of this progress was seen in the several health resorts that opened in the 1880s to promote the medicinal benefits of the county’s springs. Private academies flourished as did businesses, especially in the county seat of Harrison. But Boone County had its troubles over the years. During the Civil War bushwhackers and armies tore through the land, destroying homes, businesses, and families. In the early 1900s race riots drove out most of Harrison’s African American population and a railroad strike led to vandalism and a hanging.

A County is Born

In the 1830s and 1840s, homesteaders looking for free land came by river and military road to the area then known as Carroll County. They built log cabins, hunted and farmed, established post offices, and started businesses such as general stores and a bear-grease rendering plant (for lamp oil).

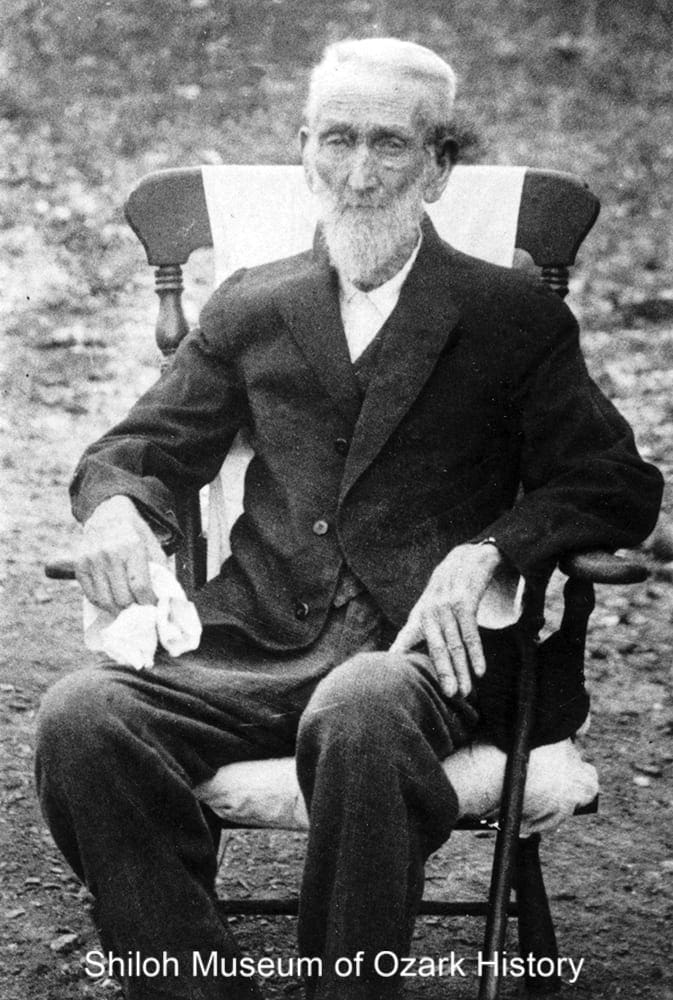

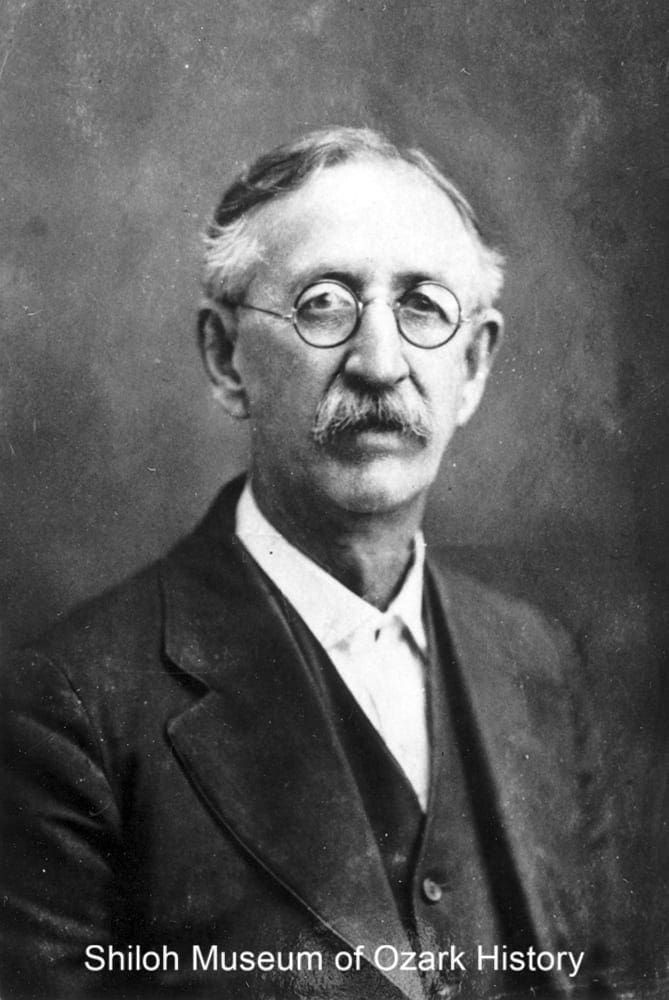

Senator James Townsend “Town” Hopper, sponsor of legislation to create Boone County, early 1900s. Jessalee Nash/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-127-69)

After the strife of the Civil War, Union and Confederate forces fought once again, but this time for positions of leadership. James Townsend Hopper, a former Union soldier, was elected to the state Senate. There he sponsored legislation to create a new county, since local government was controlled by ex-Confederates. In April 1869, with the help of a Republican legislature, land from the east side of Carroll County was taken and Boone County was born.

The County Seat

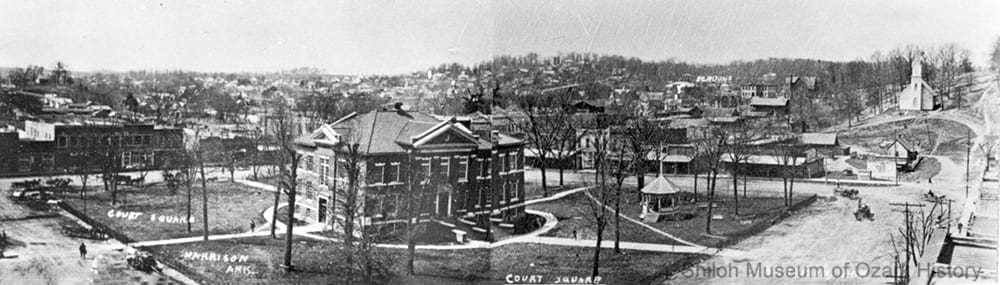

Looking southwest at Harrison, with the courthouse in the center, about 1910. Mrs. F. L. Coffman/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-23)

When Boone County was created in 1869, Harrison became the county seat. Originally called Crooked Creek, the name was changed when Captain Henry W. Fick asked civil engineer M. LaRue Harrison, both former Union soldiers, to survey the town. Fick was Harrison’s postmaster and developed many business interests in the pro-Union, pro-Republican town.

A few years later folks petitioned to move the county seat to Bellefonte, a long-established community that had supported the Confederacy. Worried about losing business in Harrison, Fick found like-minded former Confederates to help him campaign. It was a close vote, but the seat stayed in Harrison. Residents’ fears of violence from the losing side came to nothing.

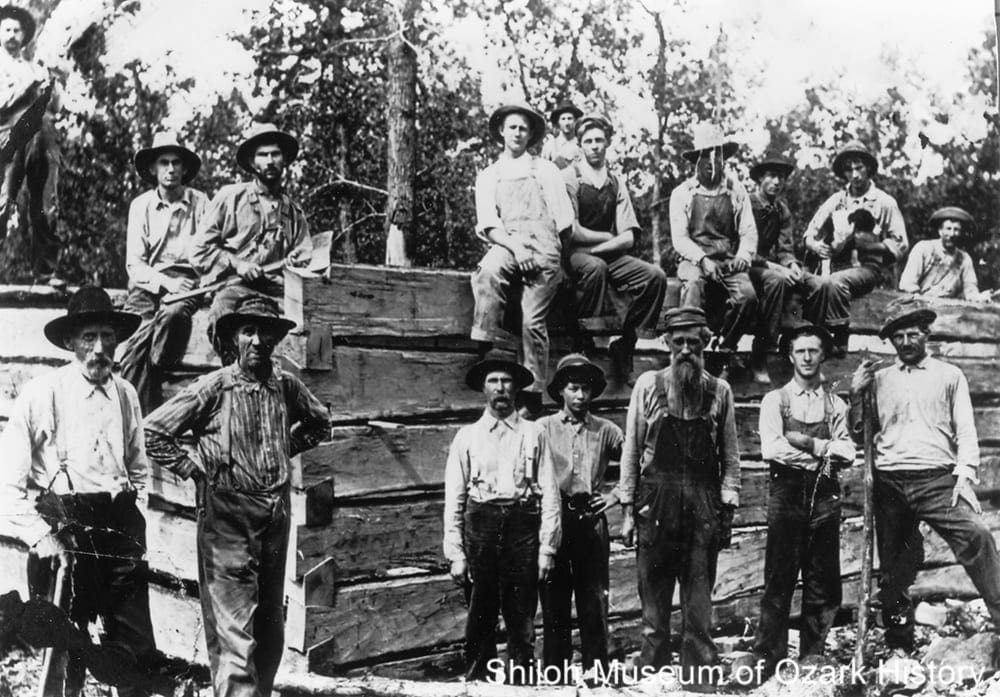

Courthouse construction crew, Harrison, about 1907. The previous courthouse burned down in 1906. Robert Flippo/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-50)

For many years the county seat of Harrison looked like the Old West with dirt streets, roaming livestock, and the dangerous “Dead Man’s Corner,” scene of many a fight and shooting.

Harrison grew dramatically in population with the coming of the railroad in 1901. More people meant more businesses, homes, and infrastructure—things like sewers, roads, and utilities.

The town’s first street improvement district was created in 1924. Streets in the business district were paved and a sewer system was built. But by 1936 only 10 percent of the town’s streets were surfaced. Believing Harrison couldn’t continue to grow without improvement, downtown merchant Layton Coffman successfully led a campaign to pave streets citywide.

Springs and Creeks

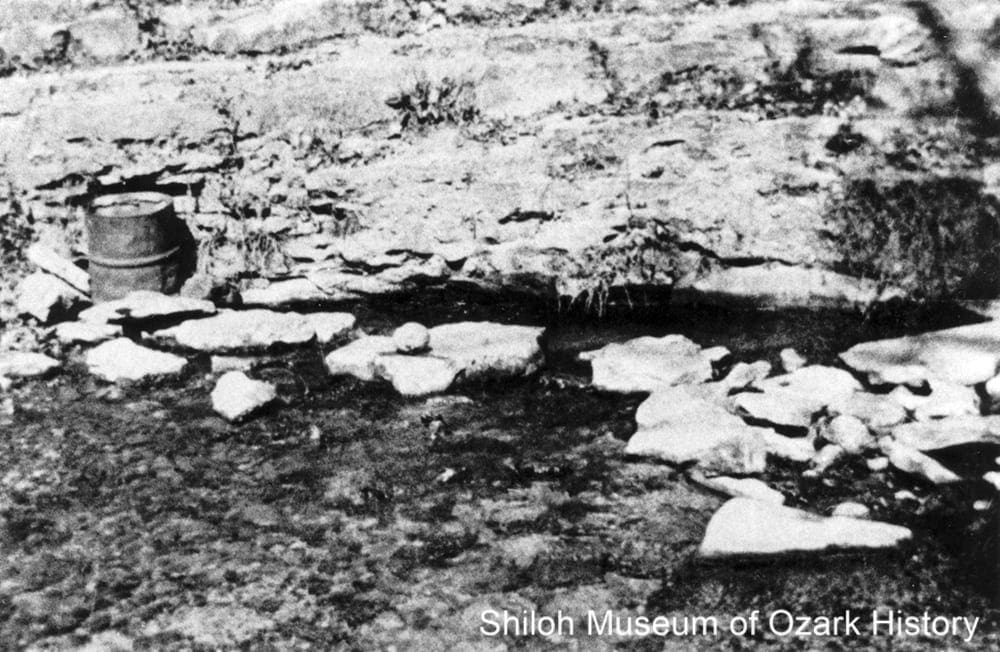

Bellefonte Spring, about 1912. Bellefonte (“beautiful fountain”) was one of many communities founded around a spring. Eula Albright/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-127-58)

Springs and creeks were important to settlers. Creeks provided energy for grist mills and cotton gins. Springs offered medicinal and business opportunities. In the 1880s, Eureka Springs in nearby Carroll County became a prosperous health resort as people flocked to “take the waters” and cure their ailments.

Boone County had three resorts. The most popular was in the town of Elixir Springs, where the spring’s water was said to cure rheumatism and blood diseases. About 1,000 people lived and worked in the town in the early 1880s. But the resort and the town’s life were short lived. By 1892 it and another resort at Tom Thumb Springs were long gone.

Mountain Meadows Massacre

Milum Spring, south of Harrison, early 1900s. Roger V. Logan Jr./Boone County Library Collection (S-87-129-59)

In April 1857, under the leadership of Captain Alexander Fancher, a large company of County residents and others formed a caravan at Milum Spring and headed for new opportunities in California.

In September they stopped at Mountain Meadows, a valley in the Utah Territory. There they were attacked by Mormons and Native Americans. They battled several days, after which the survivors where allowed to leave, only to be brutally attacked one more time. Seventeen children deemed too young to tell the tale were allowed to live.

The reasons for this terrible massacre and the actions taken by the various parties is still hotly debated by historians, descendents, and church leaders. After many years of denial, a small monument to the victims now stands in the valley.

Civil War

In the hills of Northern Arkansas, where slavery wasn’t as common as it was in the Delta, most folks weren’t interested in leaving the Union. After much legislative debate and voting, Arkansas seceded in May 1861. County residents were forced to choose sides—Union or Confederate.

Most of the county’s men formed companies and went off to fight. Some saw action at the Battles of Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove. Those left behind faced hardships, too. Armies destroyed a gunpowder mill on Crooked Creek and a niter works (explosives) at Dubuque and they took livestock, food, and grain. Violent bushwhackers took what was left and often burned homes when they weren’t satisfied.

Homes and Farms

The first settlers built hand-hewn log cabins and lived a simple, hard life. As communities and towns grew, roads and a railroad were built. New architectural styles and fancy construction materials made their way into the county, allowing prosperous businessmen to build large, showy homes.

By the early 1900s many in the African American community in Harrison owned their own homes. They were often located in the less desirable parts of the town, although a few families lived in white neighborhoods.

Threshing on the Vol Denton farm, Alpena, June 30, 1911. As a stream-driven thresher moved its way through the fields, the top rails of a split-rail fence were often fed as fuel into the firebox; the rails were later replaced. Steve Erwin Collection (S-97-144-49)

Boone County’s prairies and cleared lands offered farmers a good place to plant crops and feed their livestock. An 1883 newspaper article declared that county soil was “well adapted to the production of corn, wheat, cotton, tobacco, grass, sorghum, oats, barley, etc., etc.”

Early settlers grew vegetables and grains to feed themselves. It was only later that crops were grown for market. In 1905 the Lead Hill area shipped out about 5,000 bales of cotton. In 1913 “Black Ben Davis” apples were shipped from the Hickory Grove farm near Harrison.

Businesses

Soon after settlers first arrived in the county, businesses like general stores began to spring up. By 1885 Harrison had a number of stores that sold food, medicine, clothing, furniture, saddles, and hardware. Specialized shops included a bakery, ice cream and candy makers, and a man who made tinware. Residents from neighboring communities flocked to town on Saturdays to shop and socialize.

The coming of the railroad in 1901 meant that more goods were brought into the county and farm products and natural resources like lumber and ores were sent to market. In the 1910s fresh eggs were shipped to Memphis in railroad cars cooled with ice.

By 1847 four legal, tax-paying distilleries operated in Carroll County. Many more illegal stills were likely hidden in the hills by folks who refused to pay the alcohol tax. The manufacture of moonshine grew in the 1890s when the government raised alcohol taxes, and from 1915 to 1935 during Prohibition, when alcohol was severely limited nationwide.

After World War II, returning veterans found their county overrun with bootleggers. They re-sold alcohol illegally at a premium to folks who lived in a “dry” county like Boone which didn’t allow alcohol sales. Determined to put an end to the lawbreakers, one group pushed for the legalization of alcohol sales while another tried to rid local government of do-nothing officials.

In the end, it took a double murder on the Harrison square in 1946 before the town’s sheriff and city administration finally dealt with the lawlessness.

Education

Early county schools were one-room log buildings, with one teacher for all grades. Rural students tended to complete fewer grades and had shorter terms than students in town. This was due in part to community funding problems and the students’ need to work at home and on the farm.

In the 1870s academies were established in Bellefonte, Rally Hill, and Valley Springs. The Harrison College and Normal Institute (a training school for teachers) was later established for females. These schools provided a comprehensive education for those who could afford the fees. Big towns like Harrison built impressive public schools.

During the 20th century consolidation reduced the number of school districts from 99 to six. By 1935 every student had access to a high school education.

The Railroad

In 1883 a railway line was built into Carroll County, spurring economic growth and tourism. Boone County wanted an extension of the line, but the expense and difficulty of building in the mountains kept financial backers away.

For 20 years folks made do with a daily stagecoach run between Eureka Springs and Harrison. Eventually backers were found and residents gave land and cash to smooth the way. In March 1901 the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad steamed into Harrison where it was greeted with band music and speeches. Later the line pushed eastward into the county and became the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad.

The railroad brought goods and people into the county and sent produce, livestock, and natural resources like timber and mineral ores all over the nation.

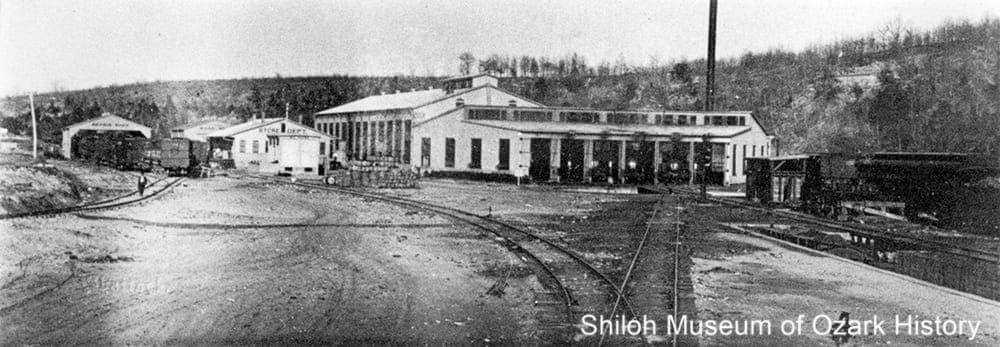

Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad shops, looking northwest, Harrison, about 1915. Mrs. F. L. Coffman/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-129-47)

The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad had a troubled existence. By 1921 financial problems led to a major wage cut. Union workers went on strike and the line closed down, causing hardship for many families and businesses. Although a group of investors bought the railroad and resumed operations, the workers remained on strike.

Tensions increased in Harrison as strike-breakers crossed the picket line and vandalism occurred. On January 14, 1923, hundreds of armed men arrived by train and car. They searched homes for union literature and firearms, threatened strikers, and burned the Union Hall. The violence grew. Before it was over one man was hanged from a railroad bridge. Fearing for their lives, strikers and their families fled. The union was busted.

Another strike in 1946 effectively ended the railroad line.

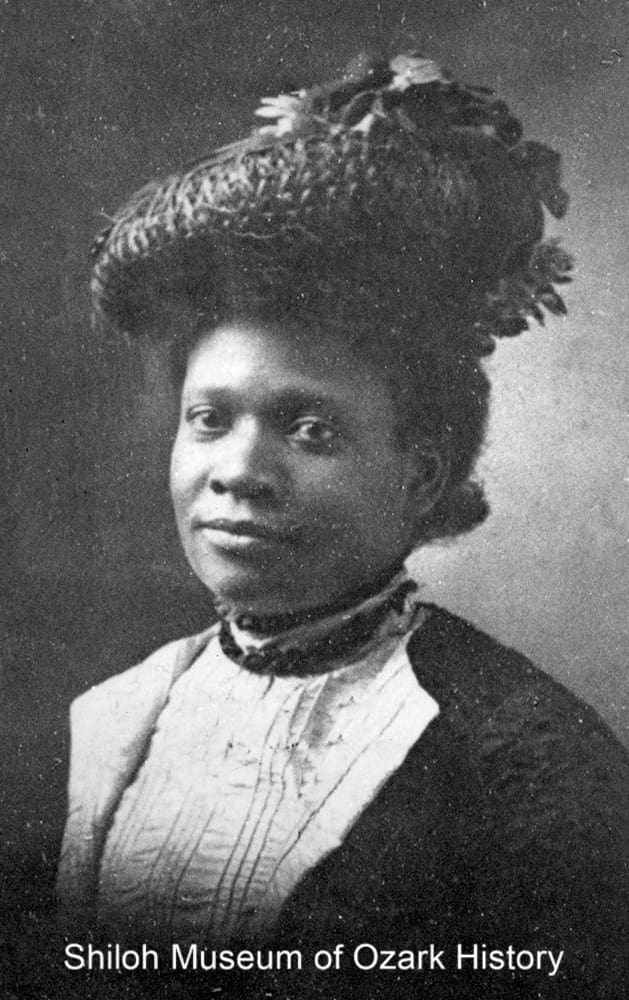

African Americans

In 1900 just over 100 African Americans lived in Harrison, which had a total population of more than 1,500. Many had been in the area for a long time and had established churches, a school, and businesses. A division existed along race lines but, for the most part, life was peaceful. Things changed as racial intolerance spread across the country and “justice” increasingly meant the use of violence.

Tensions increased in Harrison when a number of homeless, unemployed African-American railroad laborers came to town. In 1905 a black man was jailed for breaking into a home. Mob violence erupted and blacks were beaten and their homes burned. Many fled for their lives, never to return. Three years later a youth was accused of robbery and rape. Once again the black community feared mob violence and fled. By 1910 “Aunt Vine” Smith was the only African American left in Harrison.

The 2010 census listed a few dozen blacks in Boone County, home to the Arkansas faction of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Mining and Timber

Town names such as Lead Hill and Zinc attest to the importance of mining in Boone County. In the1850s small mines near Dubuque and Lead Hill used crude smelters to extract lead from rock.

Mining began in earnest in the 1870s and it was hard work. Hand tools were used to dig pits in the ground or shafts into the sides of mountain. Tons of ore-bearing rock were processed on site or sent to distant smelters. In 1886, 33 wagon-loads of ore (34,320 pounds) were shipped from the Bonanza Mine near Lead Hill down the White River to Batesville, and then on to St. Louis by rail.

A zinc “rush” began around 1899. Zinc was used as a pigment in paints, for battery electrodes, and for galvanizing iron. During World War I zinc prices soared only to fall at war’s end. Many mines were abandoned and towns shrank or disappeared.

Cutting staves, Richland Creek, early 1900s. Earl Henry/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-34)

Early settlers found large stands of oak, hickory, cedar, walnut, cherry, and pine. Railroads headed for Northwest Arkansas in the 1880s in part to take advantage of its vast timber reserves. Logging became a major industry, creating jobs and boom towns along the line.

Once saws and axes felled the giant trees, teams of mules hauled the logs to sawmills and factories where the timber was turned into barrel staves, railroad ties, lumber, fence posts, and tool handles. When the trees were gone in one area, operations moved to the next. New settlers farmed the cleared land.

A circa-1883 forestry report predicted a 300-year supply of timber. By the 1920s the forests were largely gone. The timber boom was over.

Gatherings

Methodist Sunday School group enjoying dinner on the ground, Wilson Spring, early 1900s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-71)

People came together in a variety of ways. Picnics on the Fourth of July were common, as were “dinners on the ground,” often organized by churches. On Decoration Day families tidied up cemeteries and placed flowers on graves. Log-raisings to build barns and homes were held when a new family moved into the neighborhood. The Boone County fair started in 1887 and offered livestock contests, mule racing, and arts and crafts exhibitions.

Traveling preachers held meetings and sometimes debated one another. Fiddle music and dancing were popular but some churches frowned on this pastime. “Play parties” were a way to get around this. Rather than use instruments to make music, songs were sung and participants did a type of square dance.

In all of these activities, folks had a chance to get together to strengthen community and social bonds and meet eligible partners.

Independence Day celebration, Hill Top, 1910s. The women may be students of the Hill Top Mission School. Steve Erwin Collection (S-97-144-86)

For many decades Independence Day was a time for communities to come together and have a good time.

The town of Harrison was incorporated in March 1876. In celebration, city fathers planned a grand event for the Fourth of July which, that year, fell on the Centennial of the nation’s founding. Over 3,000 folks listened to bands, picnicked, heard readings of the Declaration of Independence and other patriotic speeches, and watched fireworks.

A joust was held at the race track. Men riding horses and holding pointed sticks raced towards posts that held rings suspended by wire. The winner was the first to spear the ring with his stick. First prize was $20.

Riverside baptism at Omaha, 1909. Brother Voiles, minister. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-125)

Early settlers brought their religion with them, often worshipping in their homes. One of the first churches was Crooked Creek Primitive Baptist Church, founded in 1834. Churches formed and split frequently as communities changed or members differed on church teachings.

Traveling preachers and circuit riders (pastors on horseback who visited the several churches in their care every few weeks) held services where they could—in homes, fields, and even the county courthouse. A revival meeting at Harrison led to several baptisms and the 1890 formation of the First Baptist Church.

A mission school was founded in Hill Top. In Harrison the Methodists built a college, only to have it burn down before school started.

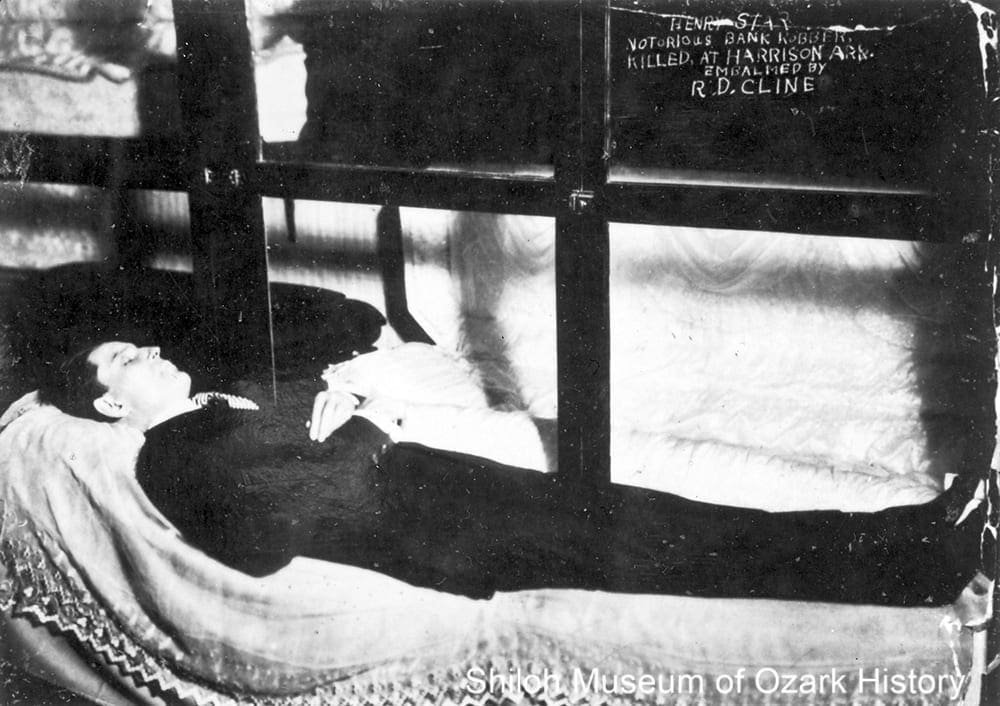

1921 Bank Robbery

In February 1921 notorious outlaw Henry Starr was one of several men who tried to rob the Peoples National Bank on Harrison’s square. Before the robbery they cut telephone lines and surveyed the bank and square.

The bank’s former president, William J. Meyers, happened to be in the bank that day. Once the cashier opened the safe the thieves began grabbing money. A distraction caused by an uncooperative patron turned their attention away from the safe, allowing Meyers a chance to grab the .38 caliber Winchester rifle stored in the vault. He shot and wounded Starr. Starr told his men to flee; eventually they were caught and tried. Starr died a few days after the robbery.

The area which is now Boone County was once home to Native Americans like the Osage. Spanish and French explorers later came through, followed by settlers from Tennessee, Kentucky, and other southern states. The land was heavily forested and hilly, so new arrivals came by river until roads could be built for wagons. In December 1818 explorer Henry R. Schoolcraft stopped at Sugarloaf Prairie near Lead Hill and said this of the inhabitants:

The area which is now Boone County was once home to Native Americans like the Osage. Spanish and French explorers later came through, followed by settlers from Tennessee, Kentucky, and other southern states. The land was heavily forested and hilly, so new arrivals came by river until roads could be built for wagons. In December 1818 explorer Henry R. Schoolcraft stopped at Sugarloaf Prairie near Lead Hill and said this of the inhabitants:

They raise corn for bread, and for feeding their horses previous to the commencement of long journeys in the woods, but none for exportation. No cabbages, beets, onions, potatoes, turnips, or other garden vegetables are raised. Gardens are unknown. Corn and other wild meats, chiefly bear’s meat, are the staple articles of food. In manners, morals, customs, dress, contempt for labor and hospitality, the state of society is not essentially different from that which exists among the savages.

An east-west military road, also known as the Washington Road, was built in the days when the area was part of a much larger Carroll County. Boone County was created in 1869 from a large chunk of Carroll County; a few years later a small portion of Marion County was added. The county wasn’t named after Daniel Boone, as some have claimed. Rather, its beautiful land was said to be a boon (a gift) to its settlers.

Farmers found prairies and other land suitable for grazing livestock and planting such crops as cotton, corn, and fruit. Zinc and lead were mined and forests were heavily logged for such products as railroad ties, lumber, barrel staves, and tool handles. The coming of the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad in 1901 meant that more of Boone County’s products could be shipped to market. In 1905 the Harrison Times wrote:

“There is stamped upon our people the signet of enterprise and broad-gauged public spirit; we are moving steadily onward in wealth, material prosperity and advances of culture with the courage of self-assertion. . . . Enterprise is planning new forms; labor a new impetus; brain and brawn are at work and we are moving steadily onward and upward in progress and advancement.”

Some of this progress was seen in the several health resorts that opened in the 1880s to promote the medicinal benefits of the county’s springs. Private academies flourished as did businesses, especially in the county seat of Harrison. But Boone County had its troubles over the years. During the Civil War bushwhackers and armies tore through the land, destroying homes, businesses, and families. In the early 1900s race riots drove out most of Harrison’s African American population and a railroad strike led to vandalism and a hanging.

A County is Born

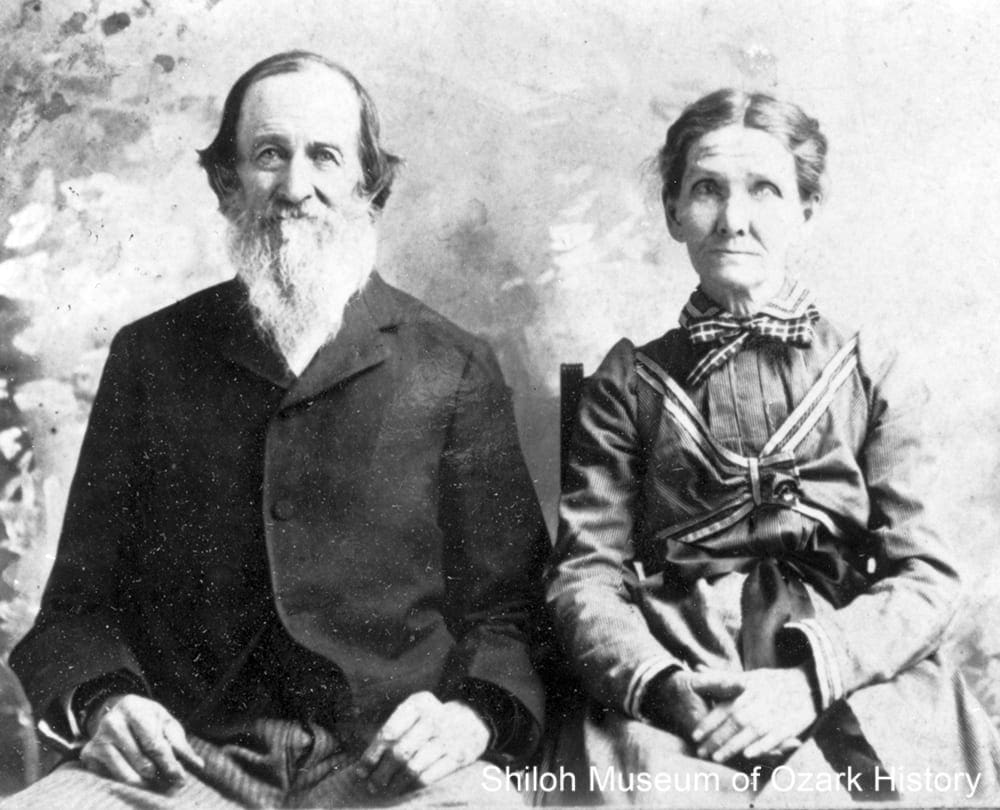

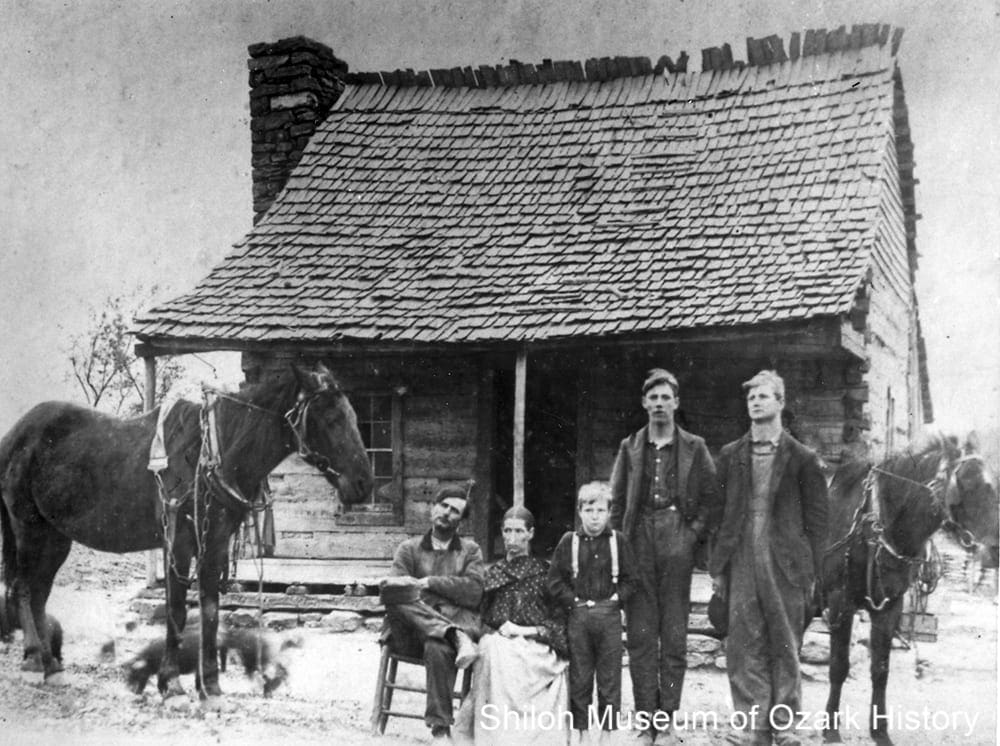

James O. and Mary Snelson Nicholson, early pioneers, about 1900. J. W. Nicholson/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-38-7)

In the 1830s and 1840s, homesteaders looking for free land came by river and military road to the area then known as Carroll County. They built log cabins, hunted and farmed, established post offices, and started businesses such as general stores and a bear-grease rendering plant (for lamp oil).

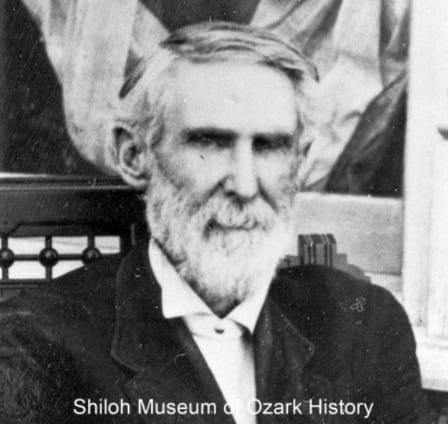

Senator James Townsend “Town” Hopper, sponsor of legislation to create Boone County, early 1900s. Jessalee Nash/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-127-69)

After the strife of the Civil War, Union and Confederate forces fought once again, but this time for positions of leadership. James Townsend Hopper, a former Union soldier, was elected to the state Senate. There he sponsored legislation to create a new county, since local government was controlled by ex-Confederates. In April 1869, with the help of a Republican legislature, land from the east side of Carroll County was taken and Boone County was born.

The County Seat

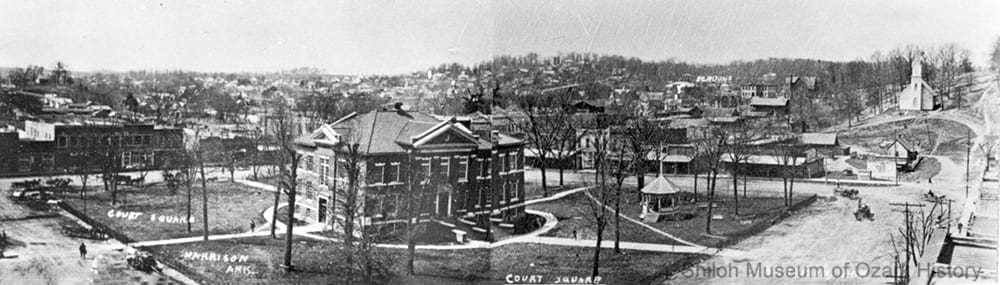

Looking southwest at Harrison, with the courthouse in the center, about 1910. Mrs. F. L. Coffman/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-23)

When Boone County was created in 1869, Harrison became the county seat. Originally called Crooked Creek, the name was changed when Captain Henry W. Fick asked civil engineer M. LaRue Harrison, both former Union soldiers, to survey the town. Fick was Harrison’s postmaster and developed many business interests in the pro-Union, pro-Republican town.

A few years later folks petitioned to move the county seat to Bellefonte, a long-established community that had supported the Confederacy. Worried about losing business in Harrison, Fick found like-minded former Confederates to help him campaign. It was a close vote, but the seat stayed in Harrison. Residents’ fears of violence from the losing side came to nothing.

Courthouse construction crew, Harrison, about 1907. The previous courthouse burned down in 1906. Robert Flippo/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-50)

For many years the county seat of Harrison looked like the Old West with dirt streets, roaming livestock, and the dangerous “Dead Man’s Corner,” scene of many a fight and shooting.

Harrison grew dramatically in population with the coming of the railroad in 1901. More people meant more businesses, homes, and infrastructure—things like sewers, roads, and utilities.

The town’s first street improvement district was created in 1924. Streets in the business district were paved and a sewer system was built. But by 1936 only 10 percent of the town’s streets were surfaced. Believing Harrison couldn’t continue to grow without improvement, downtown merchant Layton Coffman successfully led a campaign to pave streets citywide.

Springs and Creeks

Bellefonte Spring, about 1912. Bellefonte (“beautiful fountain”) was one of many communities founded around a spring. Eula Albright/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-127-58)

Springs and creeks were important to settlers. Creeks provided energy for grist mills and cotton gins. Springs offered medicinal and business opportunities. In the 1880s, Eureka Springs in nearby Carroll County became a prosperous health resort as people flocked to “take the waters” and cure their ailments.

Boone County had three resorts. The most popular was in the town of Elixir Springs, where the spring’s water was said to cure rheumatism and blood diseases. About 1,000 people lived and worked in the town in the early 1880s. But the resort and the town’s life were short lived. By 1892 it and another resort at Tom Thumb Springs were long gone.

Mountain Meadows Massacre

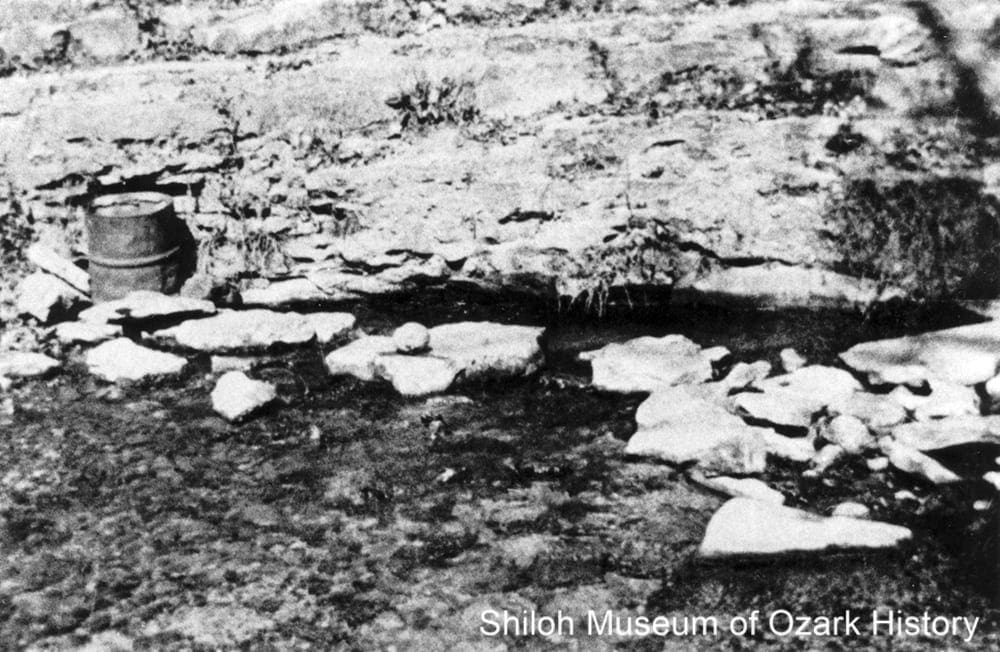

Milum Spring, south of Harrison, early 1900s. Roger V. Logan Jr./Boone County Library Collection (S-87-129-59)

In April 1857, under the leadership of Captain Alexander Fancher, a large company of County residents and others formed a caravan at Milum Spring and headed for new opportunities in California.

In September they stopped at Mountain Meadows, a valley in the Utah Territory. There they were attacked by Mormons and Native Americans. They battled several days, after which the survivors where allowed to leave, only to be brutally attacked one more time. Seventeen children deemed too young to tell the tale were allowed to live.

The reasons for this terrible massacre and the actions taken by the various parties is still hotly debated by historians, descendents, and church leaders. After many years of denial, a small monument to the victims now stands in the valley.

Civil War

Richard R. and Nancy A. Hopper Capps, near Hopewell, early 1900s. Capps first served in Co. H, 2nd Regiment Missouri Light Artillery (a Union force). Roger V. Logan, Jr./Boone County Library Collection (S-87-129-44)

In the hills of Northern Arkansas, where slavery wasn’t as common as it was in the Delta, most folks weren’t interested in leaving the Union. After much legislative debate and voting, Arkansas seceded in May 1861. County residents were forced to choose sides—Union or Confederate.

Most of the county’s men formed companies and went off to fight. Some saw action at the Battles of Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove. Those left behind faced hardships, too. Armies destroyed a gunpowder mill on Crooked Creek and a niter works (explosives) at Dubuque and they took livestock, food, and grain. Violent bushwhackers took what was left and often burned homes when they weren’t satisfied.

Homes and Farms

Reverend W.R. “Buck” Burnett family, Hill Top, 1908. Burnett was a Freewill Baptist minister who preached without pay. His daughter-in-law, who was ashamed of this house with its pigs in the yard, hid this photo for many years. Steve Erwin Collection (S-97-144-132)

The first settlers built hand-hewn log cabins and lived a simple, hard life. As communities and towns grew, roads and a railroad were built. New architectural styles and fancy construction materials made their way into the county, allowing prosperous businessmen to build large, showy homes.

By the early 1900s many in the African American community in Harrison owned their own homes. They were often located in the less desirable parts of the town, although a few families lived in white neighborhoods.

Charles W. Czech home on South Pine Street, Harrison, early 1900s. Czech owned the Jersey Roller Mill which was known for its quality flours and meals (coarse-ground grains). Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-28)

Boone County’s prairies and cleared lands offered farmers a good place to plant crops and feed their livestock. An 1883 newspaper article declared that county soil was “well adapted to the production of corn, wheat, cotton, tobacco, grass, sorghum, oats, barley, etc., etc.”

Early settlers grew vegetables and grains to feed themselves. It was only later that crops were grown for market. In 1905 the Lead Hill area shipped out about 5,000 bales of cotton. In 1913 “Black Ben Davis” apples were shipped from the Hickory Grove farm near Harrison.

Businesses

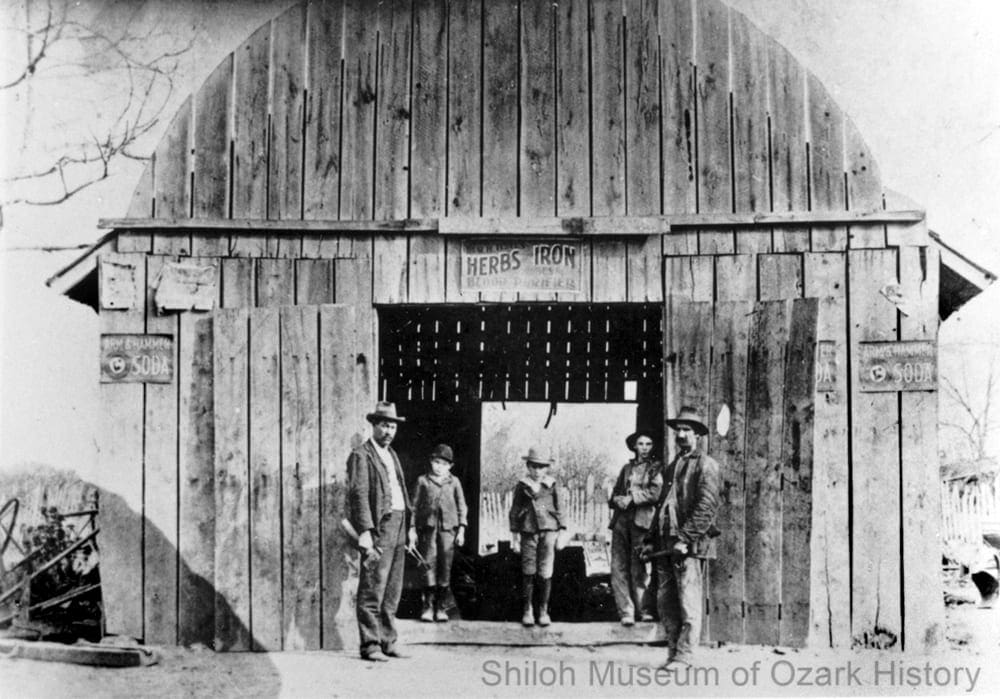

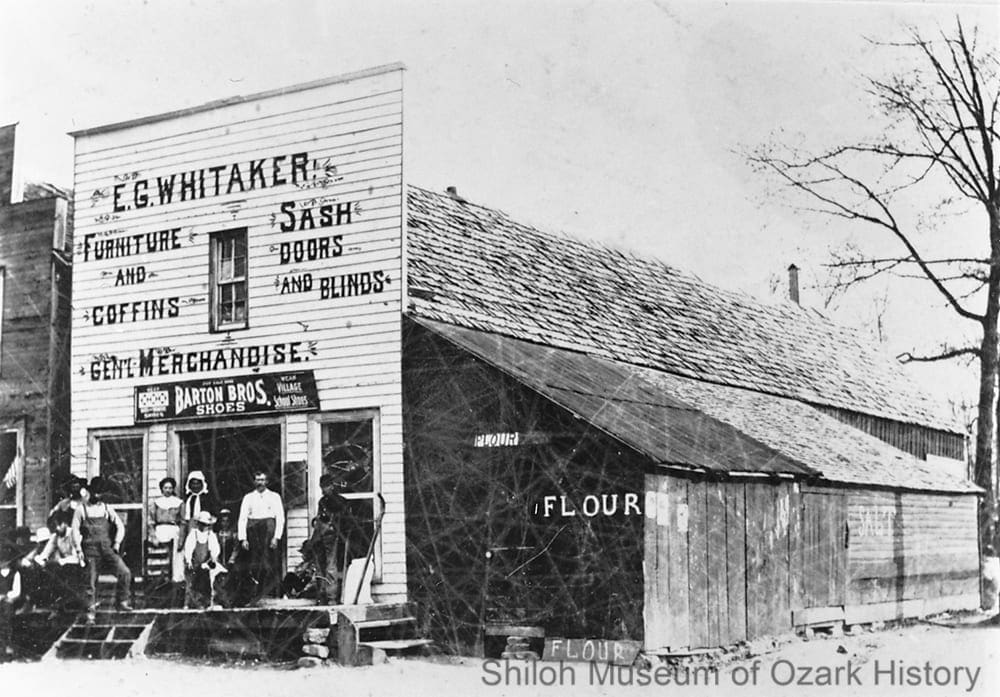

E. G. Whitaker General Store, Alpena, about 1909. Nancy Barron/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-44)

Soon after settlers first arrived in the county, businesses like general stores began to spring up. By 1885 Harrison had a number of stores that sold food, medicine, clothing, furniture, saddles, and hardware. Specialized shops included a bakery, ice cream and candy makers, and a man who made tinware. Residents from neighboring communities flocked to town on Saturdays to shop and socialize.

The coming of the railroad in 1901 meant that more goods were brought into the county and farm products and natural resources like lumber and ores were sent to market. In the 1910s fresh eggs were shipped to Memphis in railroad cars cooled with ice.

By 1847 four legal, tax-paying distilleries operated in Carroll County. Many more illegal stills were likely hidden in the hills by folks who refused to pay the alcohol tax. The manufacture of moonshine grew in the 1890s when the government raised alcohol taxes, and from 1915 to 1935 during Prohibition, when alcohol was severely limited nationwide.

After World War II, returning veterans found their county overrun with bootleggers. They re-sold alcohol illegally at a premium to folks who lived in a “dry” county like Boone which didn’t allow alcohol sales. Determined to put an end to the lawbreakers, one group pushed for the legalization of alcohol sales while another tried to rid local government of do-nothing officials.

In the end, it took a double murder on the Harrison square in 1946 before the town’s sheriff and city administration finally dealt with the lawlessness.

Education

Early county schools were one-room log buildings, with one teacher for all grades. Rural students tended to complete fewer grades and had shorter terms than students in town. This was due in part to community funding problems and the students’ need to work at home and on the farm.

In the 1870s academies were established in Bellefonte, Rally Hill, and Valley Springs. The Harrison College and Normal Institute (a training school for teachers) was later established for females. These schools provided a comprehensive education for those who could afford the fees. Big towns like Harrison built impressive public schools.

During the 20th century consolidation reduced the number of school districts from 99 to six. By 1935 every student had access to a high school education.

The Railroad

St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad train on Long Creek trestle, Alpena, April 15, 1901. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-94)

In 1883 a railway line was built into Carroll County, spurring economic growth and tourism. Boone County wanted an extension of the line, but the expense and difficulty of building in the mountains kept financial backers away.

For 20 years folks made do with a daily stagecoach run between Eureka Springs and Harrison. Eventually backers were found and residents gave land and cash to smooth the way. In March 1901 the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad steamed into Harrison where it was greeted with band music and speeches. Later the line pushed eastward into the county and became the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad.

The railroad brought goods and people into the county and sent produce, livestock, and natural resources like timber and mineral ores all over the nation.

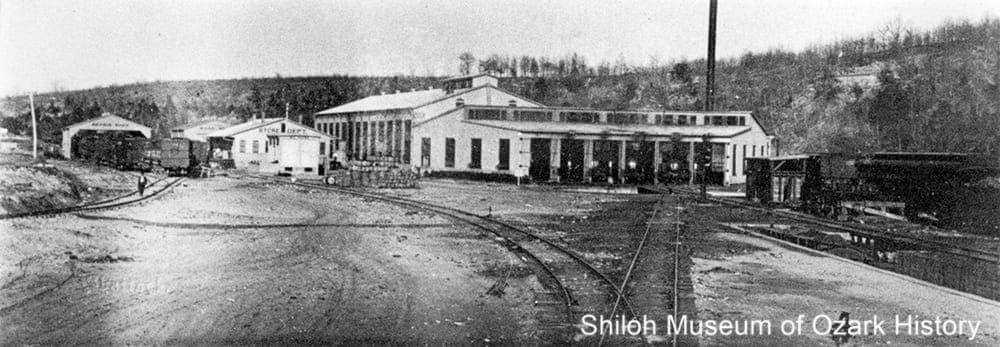

Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad shops, looking northwest, Harrison, about 1915. Mrs. F. L. Coffman/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-129-47)

The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad had a troubled existence. By 1921 financial problems led to a major wage cut. Union workers went on strike and the line closed down, causing hardship for many families and businesses. Although a group of investors bought the railroad and resumed operations, the workers remained on strike.

Tensions increased in Harrison as strike-breakers crossed the picket line and vandalism occurred. On January 14, 1923, hundreds of armed men arrived by train and car. They searched homes for union literature and firearms, threatened strikers, and burned the Union Hall. The violence grew. Before it was over one man was hanged from a railroad bridge. Fearing for their lives, strikers and their families fled. The union was busted.

Another strike in 1946 effectively ended the railroad line.

African Americans

In 1900 just over 100 African Americans lived in Harrison, which had a total population of more than 1,500. Many had been in the area for a long time and had established churches, a school, and businesses. A division existed along race lines but, for the most part, life was peaceful. Things changed as racial intolerance spread across the country and “justice” increasingly meant the use of violence.

Tensions increased in Harrison when a number of homeless, unemployed African-American railroad laborers came to town. In 1905 a black man was jailed for breaking into a home. Mob violence erupted and blacks were beaten and their homes burned. Many fled for their lives, never to return. Three years later a youth was accused of robbery and rape. Once again the black community feared mob violence and fled. By 1910 “Aunt Vine” Smith was the only African American left in Harrison.

The 2010 census listed a few dozen blacks in Boone County, home to the Arkansas faction of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Mining and Timber

Town names such as Lead Hill and Zinc attest to the importance of mining in Boone County. In the1850s small mines near Dubuque and Lead Hill used crude smelters to extract lead from rock.

Mining began in earnest in the 1870s and it was hard work. Hand tools were used to dig pits in the ground or shafts into the sides of mountain. Tons of ore-bearing rock were processed on site or sent to distant smelters. In 1886, 33 wagon-loads of ore (34,320 pounds) were shipped from the Bonanza Mine near Lead Hill down the White River to Batesville, and then on to St. Louis by rail.

A zinc “rush” began around 1899. Zinc was used as a pigment in paints, for battery electrodes, and for galvanizing iron. During World War I zinc prices soared only to fall at war’s end. Many mines were abandoned and towns shrank or disappeared.

Cutting staves, Richland Creek, early 1900s. Earl Henry/Boone County Library Collection (S-87-128-34)

Early settlers found large stands of oak, hickory, cedar, walnut, cherry, and pine. Railroads headed for Northwest Arkansas in the 1880s in part to take advantage of its vast timber reserves. Logging became a major industry, creating jobs and boom towns along the line.

Once saws and axes felled the giant trees, teams of mules hauled the logs to sawmills and factories where the timber was turned into barrel staves, railroad ties, lumber, fence posts, and tool handles. When the trees were gone in one area, operations moved to the next. New settlers farmed the cleared land.

A circa-1883 forestry report predicted a 300-year supply of timber. By the 1920s the forests were largely gone. The timber boom was over.

Gatherings

Methodist Sunday School group enjoying dinner on the ground, Wilson Spring, early 1900s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-71)

People came together in a variety of ways. Picnics on the Fourth of July were common, as were “dinners on the ground,” often organized by churches. On Decoration Day families tidied up cemeteries and placed flowers on graves. Log-raisings to build barns and homes were held when a new family moved into the neighborhood. The Boone County fair started in 1887 and offered livestock contests, mule racing, and arts and crafts exhibitions.

Traveling preachers held meetings and sometimes debated one another. Fiddle music and dancing were popular but some churches frowned on this pastime. “Play parties” were a way to get around this. Rather than use instruments to make music, songs were sung and participants did a type of square dance.

In all of these activities, folks had a chance to get together to strengthen community and social bonds and meet eligible partners.

Independence Day celebration, Hill Top, 1910s. The women may be students of the Hill Top Mission School. Steve Erwin Collection (S-97-144-86)

For many decades Independence Day was a time for communities to come together and have a good time.

The town of Harrison was incorporated in March 1876. In celebration, city fathers planned a grand event for the Fourth of July which, that year, fell on the Centennial of the nation’s founding. Over 3,000 folks listened to bands, picnicked, heard readings of the Declaration of Independence and other patriotic speeches, and watched fireworks.

A joust was held at the race track. Men riding horses and holding pointed sticks raced towards posts that held rings suspended by wire. The winner was the first to spear the ring with his stick. First prize was $20.

Riverside baptism at Omaha, 1909. Brother Voiles, minister. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-125)

Early settlers brought their religion with them, often worshipping in their homes. One of the first churches was Crooked Creek Primitive Baptist Church, founded in 1834. Churches formed and split frequently as communities changed or members differed on church teachings.

Traveling preachers and circuit riders (pastors on horseback who visited the several churches in their care every few weeks) held services where they could—in homes, fields, and even the county courthouse. A revival meeting at Harrison led to several baptisms and the 1890 formation of the First Baptist Church.

A mission school was founded in Hill Top. In Harrison the Methodists built a college, only to have it burn down before school started.

1921 Bank Robbery

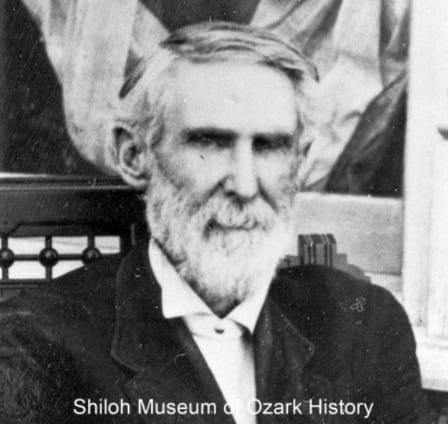

In February 1921 notorious outlaw Henry Starr was one of several men who tried to rob the Peoples National Bank on Harrison’s square. Before the robbery they cut telephone lines and surveyed the bank and square.

The bank’s former president, William J. Meyers, happened to be in the bank that day. Once the cashier opened the safe the thieves began grabbing money. A distraction caused by an uncooperative patron turned their attention away from the safe, allowing Meyers a chance to grab the .38 caliber Winchester rifle stored in the vault. He shot and wounded Starr. Starr told his men to flee; eventually they were caught and tried. Starr died a few days after the robbery.