The Changing Face of Emma

Online ExhibitBruce Vaughan’s Emma Avenue

Bruce Vaughan (1922-2013) was born in Spring Valley (Washington County), east of Springdale. He began his love affair with Emma Avenue in 1938 when his family moved to town. During his stint in the Air Force during World War II he maintained military communications equipment. He met Mary Frances Maestri at Dodson’s lunch counter on Emma. They married in 1947 and had three children—Michael, Patrick, and Sandy.

Both Mary and Bruce had a long business history on Emma. Bruce had several stores including Bruce’s Electric Shop, Bruce’s Radio, and Bruce’s Radio and TV. He pioneered television sales and installations in Arkansas, selling Springdale’s first TV set in 1949—on Emma, of course. Mary worked as a bookkeeper at First National Bank and as operator of Image One Studio, an art gallery, frame shop, and photo studio. Both Bruce and Mary were accomplished photographers. Bruce also enjoyed writing and authored several books. The following excerpts come from his 1994 publication, Emma, We Love You, a memoir of the street he knew so well. The book is still available for purchase and contains more photos and memories from Bruce Vaughn’s life on Emma Avenue.

I was the Saturday delivery boy [for the Corner Grocery in the late 1930s] . . . “Dressed” chickens were one of our big Saturday sellers . . . [My first chore] was to pick up three dozen live chickens at a produce [company] across the tracks. As soon as I unloaded the coops, Ann [McDonald and her sister Georgia Needham] started to work in the back room wringing the chicken necks . . . For the next hour chicken feathers flew so fast that it looked like a snow storm in the foul (no pun intended) smelling room.

Penrod’s Café, without question, was one of Springdale’s most loved institutions . . . The breakfast rush was over by 9:00. Then tables and booths filled quickly with businessmen and workers from the downtown area. The Wurlitzer juke box and pinball machines became quiet for a while, as conversation, and sometimes heated arguments, dominated the dining room. Sports and politics were favored topics, but often a group surrounding a table might be found discussing automobiles, aviation, religion, or even the latest movie with Betty Grable or Lana Turner, then playing at the Concord.

The Palace Barber Shop was a center of practical jokes. One favorite . . . was to whittle a potato into the shape of a piece of shaving soap, then slip it in the barber’s shaving mug. Everyone would sit around waiting for someone to . . . ask for a shave . . . With his brush [the barber] would start whipping the “soap,” trying to work up a thick lather. Even though the joke was old, it was always good for a laugh . . .

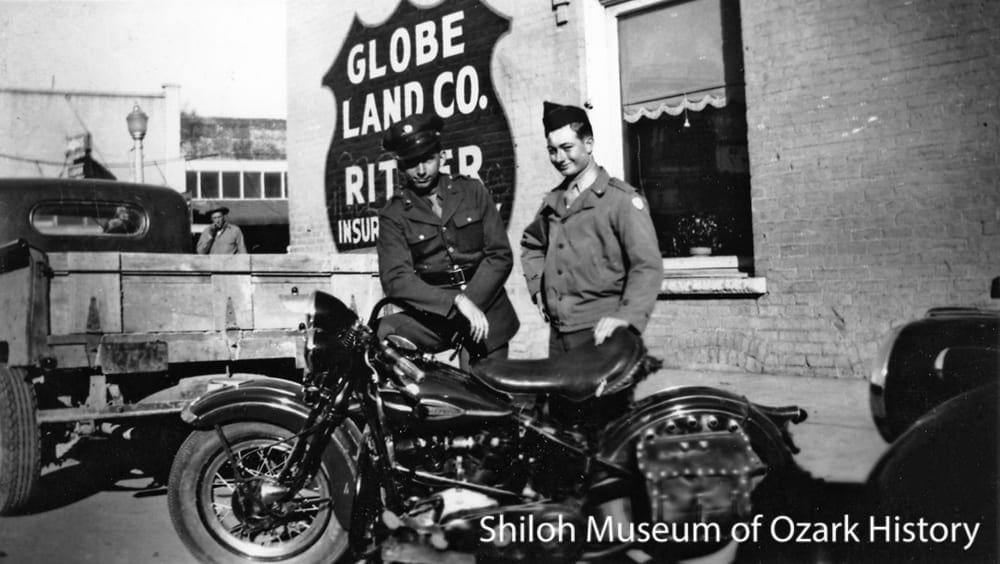

Bruce Vaughan (left) and Jim Ritter at the corner of Holcomb and Emma, January 1944. Bruce Vaughan Collection (S-96-2-1451)

The date was September 9 [1945] . . . I was now a civilian . . . My civilian clothes no longer fit. I weighed 165 pounds, some 36 pounds more than I did when I last wore them . . . A trip to Wilson’s and Lichlyter’s [department stores on Emma] that afternoon took most of my three hundred bucks mustering-out pay. I overcame my uncomfortable feeling of wearing “civvies” very quickly.

Semaphore (center) at the Frisco Depot, about 1927. R. L. Morgan, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-2001-93-25)

In 1939 I took the job of climbing the thirty-foot ladder of the semaphore [at the railroad depot] to replace the empty kerosene lantern with a full one. For this small effort they paid two dollars a month. It seemed like a good deal—until winter came, and the metal ladder became covered with ice. After a couple of trips up the icy ladder I resigned my position. [A semaphore is a type of signpost used to communicate instructions to a train’s engineer. The lantern let him see the semaphore message at night.]

Pioneer Lumber shed, 1950. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-2051)

Sliding doors on each end of the [Pioneer Lumber Co.] shed were open from 7:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. Customers could drive their trucks through the north or Emma Avenue door, pick up a load of lumber, and depart through the south door . . . This cool, shady old building was a favorite rendezvous for the town “winos,” and there were many. What could be more ideal? The liquor store was directly across the street. To the west . . . was the Blue Castle beer joint; a few doors east was the old Concord Tavern.

Though I did not realize it at the time, I was among the fortunate few who would witness, at very close range, the death of radio, the coming of television, and the invention of the transistor. In 1945, tape recorders, LP records, pocket radios, stereo, video recorders, and computers were only daydreams in the minds of a few inventors and scientists. Few today realize the social and economic changes wrought by the explosion of technology in electronics.

Liquor stores and beer joints near the railroad tracks, about 1939. Natalie Henry, photographer. Martha Hall Collection (S-96-112-21)

Those who wished to avoid the sight of violence and bloodshed knew it was wise to avoid . . . the north side of Emma between Spring Street and the Frisco tracks. Few Saturdays passed without one or more angry confrontations. Often these differences of opinion lead to a fistfight among some of our “hell raisers.” I would not say that all of Springdale’s sin was concentrated in this one block. However, a number of earthly pleasures—both legal and illegal, available in other sections of our fair city—were found here in abundance.

Michael (left) and Patrick Vaughan at the Frisco depot, about 1958. Bruce Vaughan, photographer. Mary Maestri Vaughan Collection (S-2015-98)

Beyond the semaphore [at the Frisco depot] . . . was an unused, locked, dark green door. A sign above the door read “Colored Waiting Room.” In my months working for Western Union, I never knew of a “colored” person to use the room . . . ”Civil rights” was a term as yet unfamiliar to us. One of our better restaurants, in 1950, had a short history of the city on the back of its menu. The menu proudly proclaimed: “Springdale is a city of 1,800 citizens—all white.”