CANNED GOLD

Online Exhibit

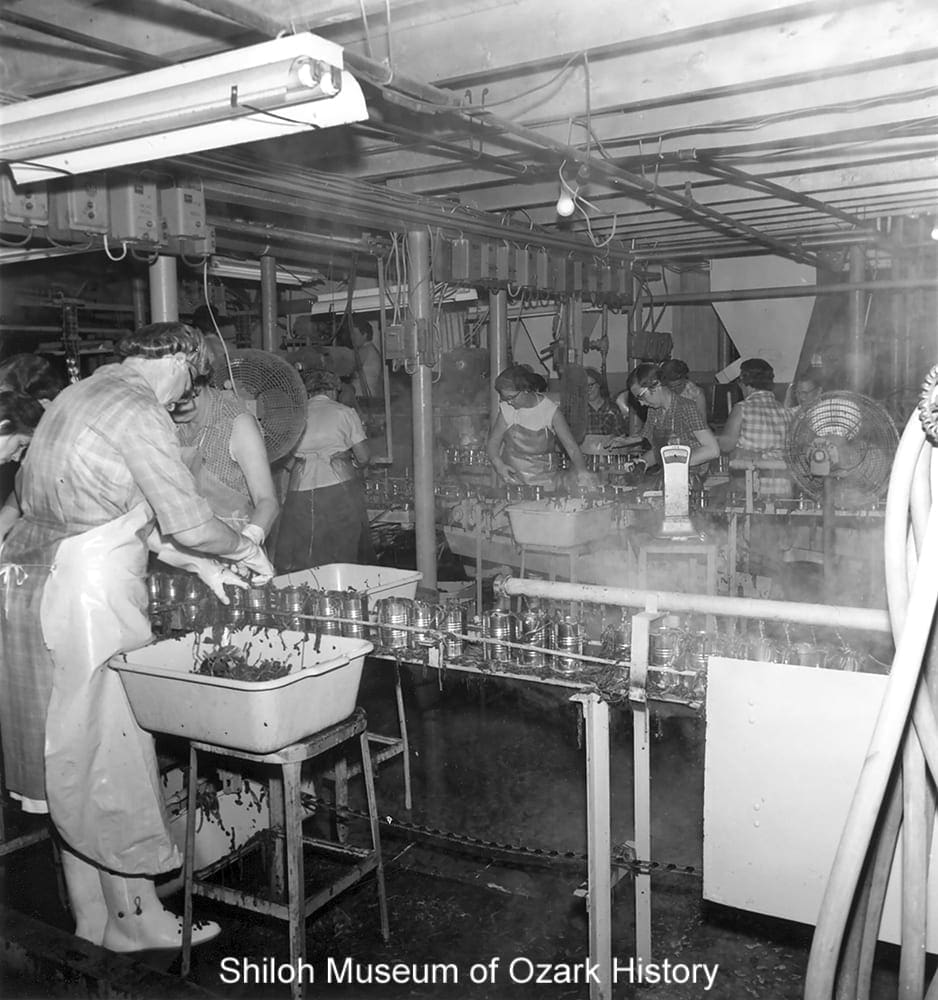

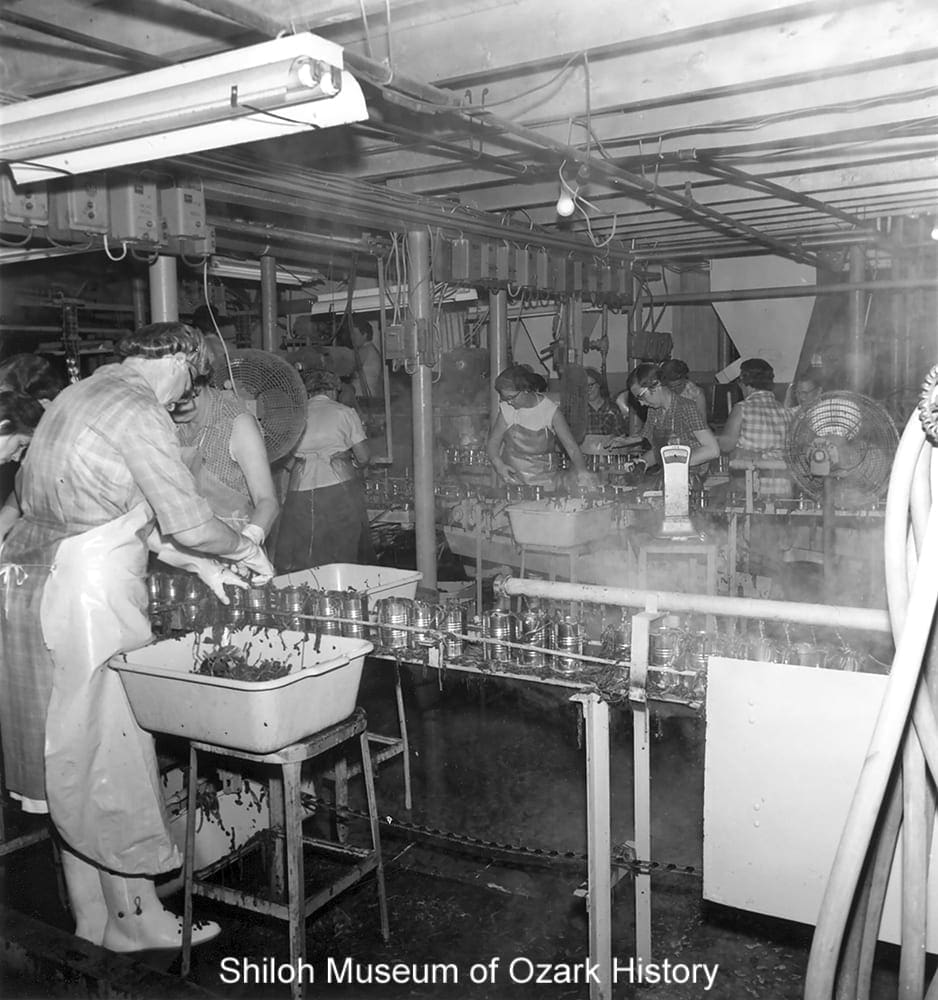

Workers packing spinach, Steele Canning Company, Lowell, April 1969. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-2040)

Commercial canning and the rise of the fruit industry in Northwest Arkansas began soon after the arrival of the Frisco Railroad in 1881. The Springdale Canning Company is believed to have been the first commercial cannery in the area. It was organized by Judge Millard Berry and other investors in 1886. At its peak it processed 10,000 cans daily.

At first workers made the cans themselves. Produce was stuffed through a two-inch-wide hole in a can’s lid, which was then patched with a piece of metal and sealed with solder. The cans were boiled to cook the food and kill harmful bacteria. Tomatoes, peaches, and apples were the first to be commercially canned, as their natural acidity helped prevent the growth of the botulinum bacteria, which causes food poisoning. Still, there was a high rate of spoilage in the early years of canning.

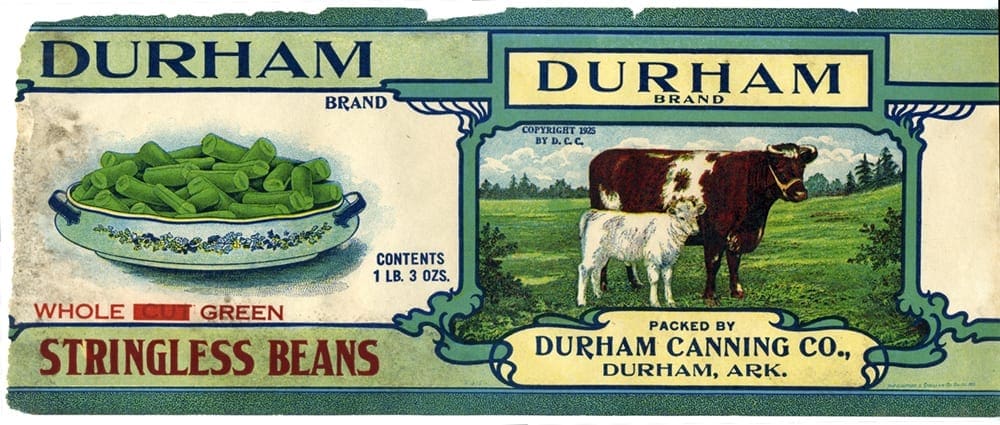

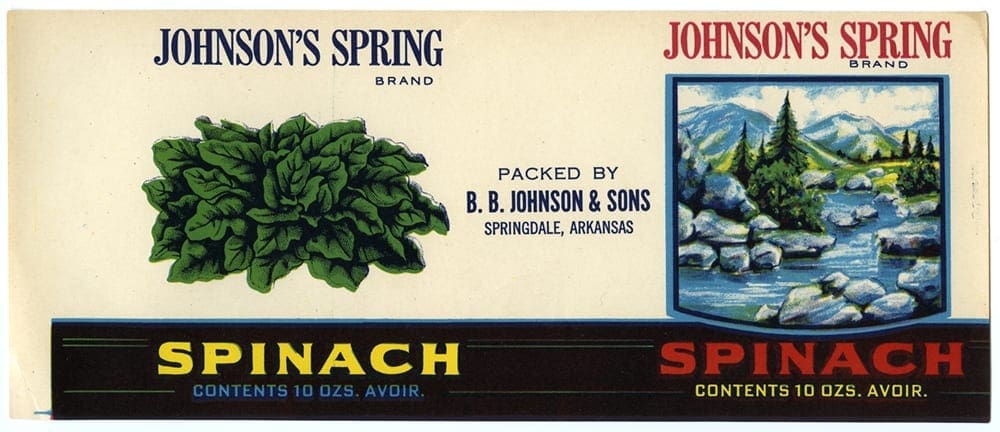

Advances in technology and food science made possible the canning of non-acidic vegetables like spinach and green beans. In the following decades numerous canneries were established, promoted in part by the railroads, which profited from freight fees charged for shipping canning supplies and finished products. From small canning sheds on the family farm to large industrial plants, canning proved to be a money-making business. To maximize their profits, a few canneries used poor-quality produce or filled their cans mostly with water.

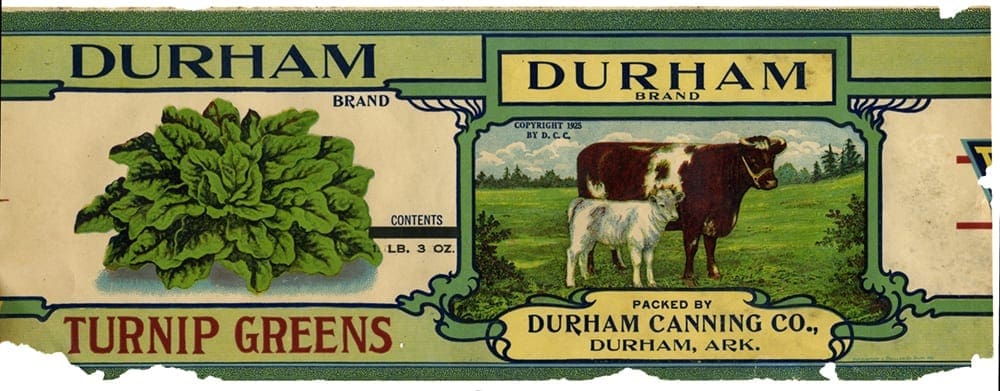

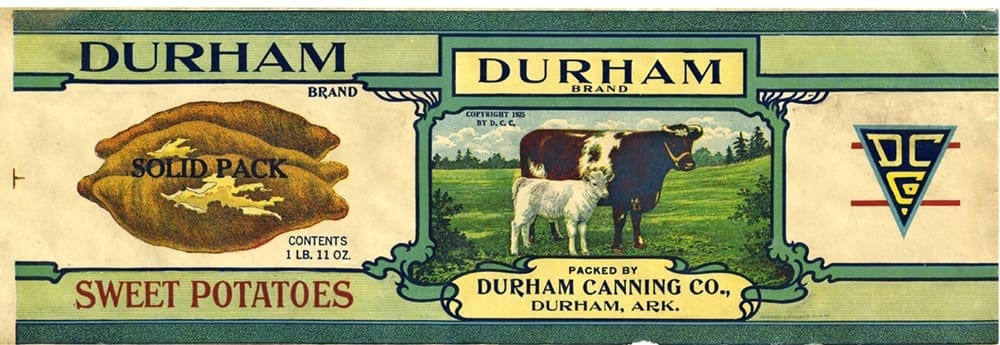

Some canneries provided farmers with seed and fertilizer, the cost of which would be deducted from the payment for their produce. Poke greens and spinach were the first to be packed in the spring, followed by green beans and tomatoes during the summer and turnip greens in the fall. It took fourteen tons (28,000 pounds) of spinach to fill the cans needed to pack one railroad boxcar. By April 1937 the Nelson Canning Company of Springdale had already shipped thirty boxcars of spinach and was expecting 400 more tons of fresh spinach in May.

Nelson’s was one of the largest operations. In addition to its steam engines and boilers, it had “eleven retorts [pressure cookers], three rotary washers, a tomato juice extractor, two pick-up belts, two steam scalders, two grape juice pressures, four cappers, four closing machines, sixteen pumps, a steam hoist, and a supply of copper kettles for the pasteurizing of grape juice.”

At the canning plant, women prepared the fruits and vegetables for processing and filled the cans. Men worked the heavier, more labor-intensive jobs such as operating the machinery and cooking the canned foods. Even though underage workers were illegal, children often lent a hand, adding cored and peeled tomatoes to their mothers’ buckets. The more buckets processed, the more money received. Even at a few cents per bucket, any extra income was helpful.

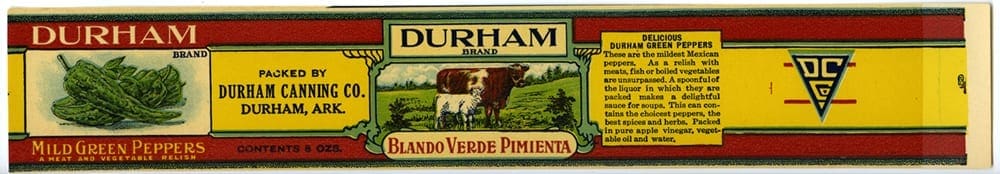

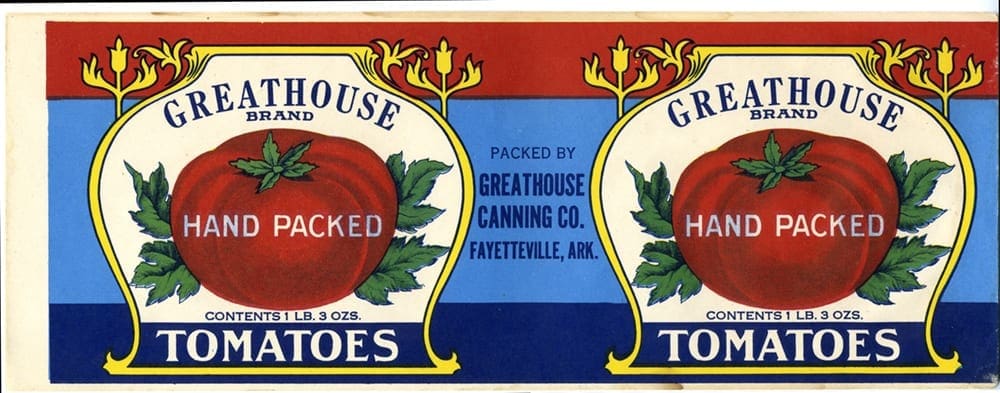

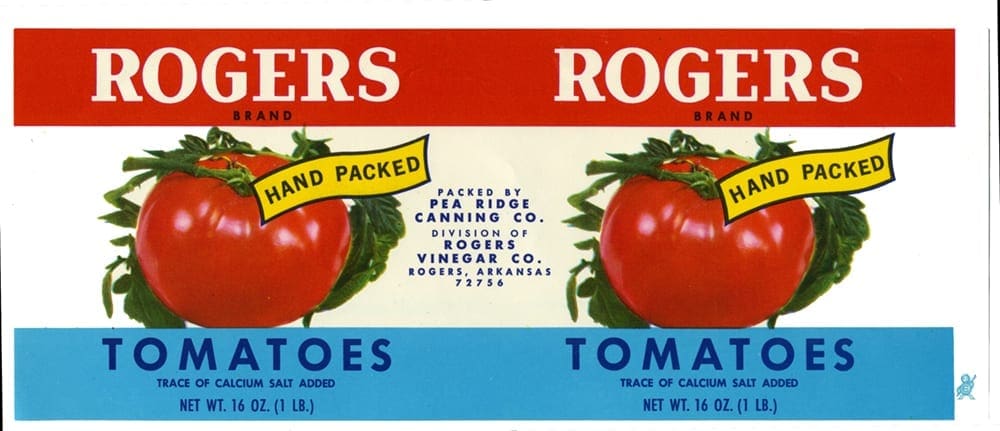

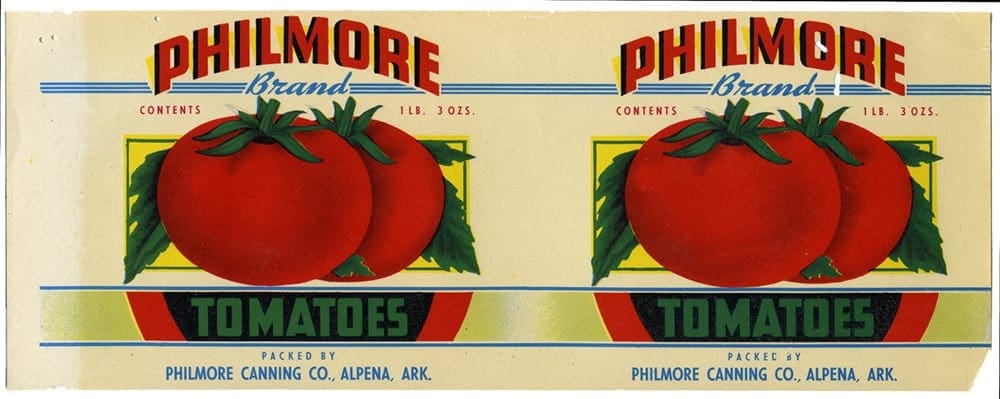

Small canneries canned under their own brand or under a national label such as Del Monte, or sold their product to brokers for resale to food distributors. Increasing mechanization of the canning process helped canneries become more competative. Additional railroad lines and newly built highways meant that produce grown outside the area could be brought in for processing, and canned goods could be shipped nationwide. By the 1940s Springdale was the center of the area’s agricultural and canning industries.

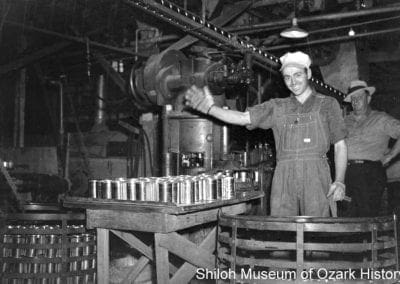

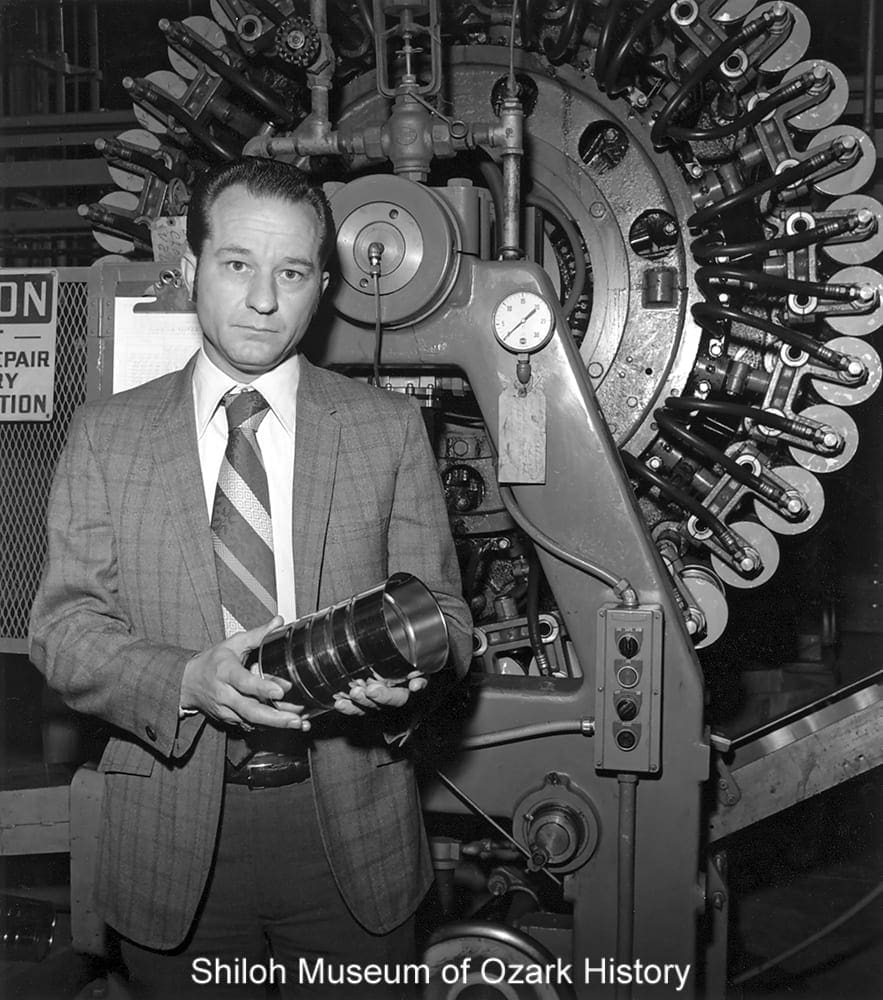

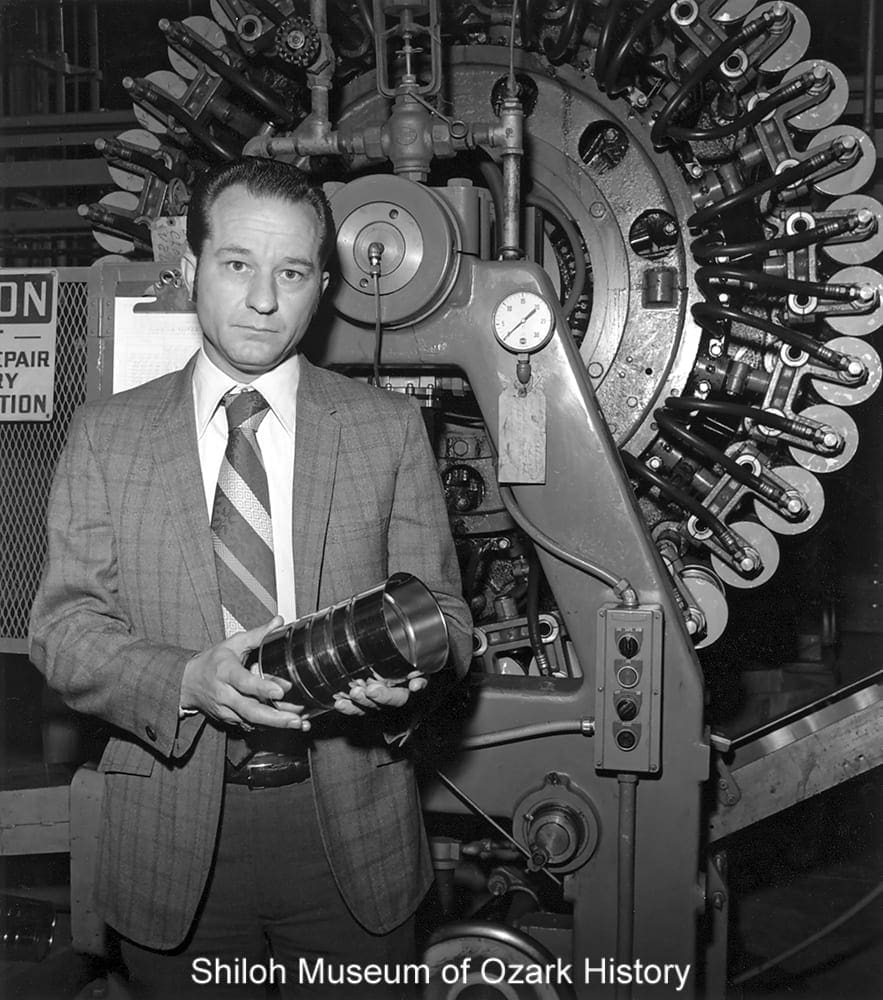

Harold Barron holding a finished can at Heekin Can Company, Springdale, January 1972. Ray Watson, photographer Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-3333)

Northwest Arkansas’ food production output ramped up during World War II. In 1943–1944, 70% of the canned goods produced by the Springdale Canning Company and the Steele Canning Company of Lowell, both co-owned by Joe M. Steele, went to feed the troops. Springdale’s green beans and spinach were found in such faraway places as Alaska, Tunisia, and New Guinea, and even under the ocean in submarines!

Stricter food safety guidelines, rising production and labor costs, and economic hardships such as drought, the Great Depression, and World War II eventually forced many small canneries out of business. But the large canneries found ways to prosper and diversify. New products like frozen cobblers, shoestring potatoes, and other types of convenience foods were introduced to meet changing consumer needs.

As the food-processing business continued to evolve, large companies bought out mid-size canneries, which were struggling to keep up with increased costs and evolving food trends. By the early 2000s Allens, Inc., of Siloam Springs was the only canner in Northwest Arkansas. During the 1970s it purchased several food processing plants in neighboring states, leading it to become, at the time, the largest independent food processor in the nation. It added dozens of new products to its lineup to maintain diversity.

Allens used state-of-the-art equipment to detect blemished produce and run its many plants efficiently. These modern industrial plants are a far cry from the days when neighbors gathered together every summer in a small canning shed to peel scalding-hot tomatoes and lower heavy baskets of canned goods into cauldrons of boiling water.

But improved manufacturing couldn’t save Northwest Arkansas’ canning industry. Consumer preferences for fresh fruits and vegetables in recent years led to expanded produce sections in grocery stores and increased buy-local purchases at farmers’ markets. The company that once was Allens was bought three times in a few short years before going out of business in 2017. Two hundred thirty workers lost their jobs.

Workers packing spinach, Steele Canning Company, Lowell, April 1969. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-2040)

Commercial canning and the rise of the fruit industry in Northwest Arkansas began soon after the arrival of the Frisco Railroad in 1881. The Springdale Canning Company is believed to have been the first commercial cannery in the area. It was organized by Judge Millard Berry and other investors in 1886. At its peak it processed 10,000 cans daily.

At first workers made the cans themselves. Produce was stuffed through a two-inch-wide hole in a can’s lid, which was then patched with a piece of metal and sealed with solder. The cans were boiled to cook the food and kill harmful bacteria. Tomatoes, peaches, and apples were the first to be commercially canned, as their natural acidity helped prevent the growth of the botulinum bacteria, which causes food poisoning. Still, there was a high rate of spoilage in the early years of canning.

Advances in technology and food science made possible the canning of non-acidic vegetables like spinach and green beans. In the following decades numerous canneries were established, promoted in part by the railroads, which profited from freight fees charged for shipping canning supplies and finished products. From small canning sheds on the family farm to large industrial plants, canning proved to be a money-making business. To maximize their profits, a few canneries used poor-quality produce or filled their cans mostly with water.

Some canneries provided farmers with seed and fertilizer, the cost of which would be deducted from the payment for their produce. Poke greens and spinach were the first to be packed in the spring, followed by green beans and tomatoes during the summer and turnip greens in the fall. It took fourteen tons (28,000 pounds) of spinach to fill the cans needed to pack one railroad boxcar. By April 1937 the Nelson Canning Company of Springdale had already shipped thirty boxcars of spinach and was expecting 400 more tons of fresh spinach in May.

Nelson’s was one of the largest operations. In addition to its steam engines and boilers, it had “eleven retorts [pressure cookers], three rotary washers, a tomato juice extractor, two pick-up belts, two steam scalders, two grape juice pressures, four cappers, four closing machines, sixteen pumps, a steam hoist, and a supply of copper kettles for the pasteurizing of grape juice.”

At the canning plant, women prepared the fruits and vegetables for processing and filled the cans. Men worked the heavier, more labor-intensive jobs such as operating the machinery and cooking the canned foods. Even though underage workers were illegal, children often lent a hand, adding cored and peeled tomatoes to their mothers’ buckets. The more buckets processed, the more money received. Even at a few cents per bucket, any extra income was helpful.

Small canneries canned under their own brand or under a national label such as Del Monte, or sold their product to brokers for resale to food distributors. Increasing mechanization of the canning process helped canneries become more competative. Additional railroad lines and newly built highways meant that produce grown outside the area could be brought in for processing, and canned goods could be shipped nationwide. By the 1940s Springdale was the center of the area’s agricultural and canning industries.

Harold Barron holding a finished can at Heekin Can Company, Springdale, January 1972. Ray Watson, photographer Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-3333)

Northwest Arkansas’ food production output ramped up during World War II. In 1943–1944, 70% of the canned goods produced by the Springdale Canning Company and the Steele Canning Company of Lowell, both co-owned by Joe M. Steele, went to feed the troops. Springdale’s green beans and spinach were found in such faraway places as Alaska, Tunisia, and New Guinea, and even under the ocean in submarines!

Stricter food safety guidelines, rising production and labor costs, and economic hardships such as drought, the Great Depression, and World War II eventually forced many small canneries out of business. But the large canneries found ways to prosper and diversify. New products like frozen cobblers, shoestring potatoes, and other types of convenience foods were introduced to meet changing consumer needs.

As the food-processing business continued to evolve, large companies bought out mid-size canneries, which were struggling to keep up with increased costs and evolving food trends. By the early 2000s Allens, Inc., of Siloam Springs was the only canner in Northwest Arkansas. During the 1970s it purchased several food processing plants in neighboring states, leading it to become, at the time, the largest independent food processor in the nation. It added dozens of new products to its lineup to maintain diversity.

Allens used state-of-the-art equipment to detect blemished produce and run its many plants efficiently. These modern industrial plants are a far cry from the days when neighbors gathered together every summer in a small canning shed to peel scalding-hot tomatoes and lower heavy baskets of canned goods into cauldrons of boiling water.

But improved manufacturing couldn’t save Northwest Arkansas’ canning industry. Consumer preferences for fresh fruits and vegetables in recent years led to expanded produce sections in grocery stores and increased buy-local purchases at farmers’ markets. The company that once was Allens was bought three times in a few short years before going out of business in 2017. Two hundred thirty workers lost their jobs.

Photo Gallery

1900s–1930s

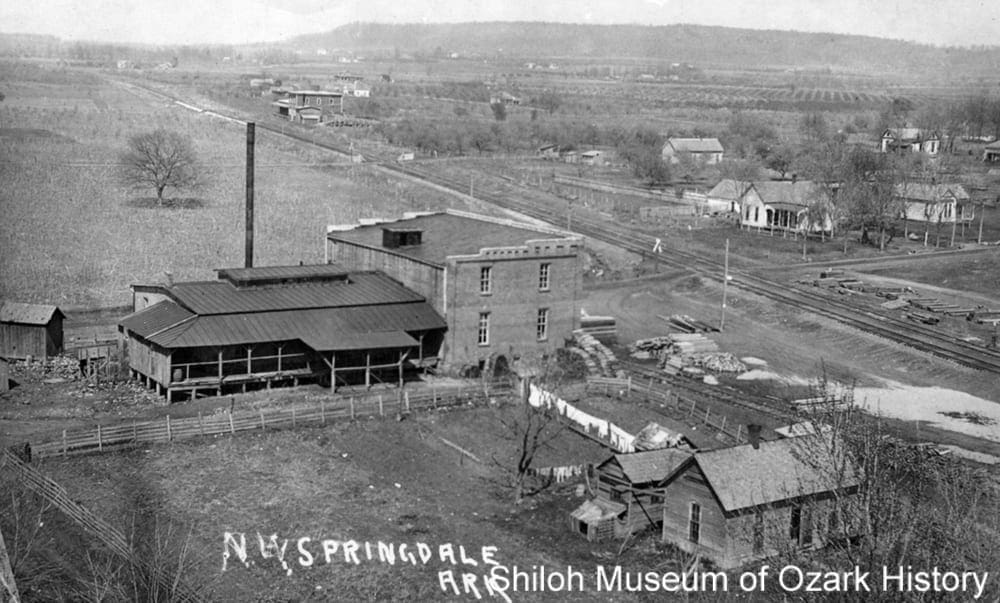

Springdale Canning Company, looking northeast towards the intersection of Huntsville Road and the Frisco Railroad tracks, Springdale, about 1908. Speece and Allen, photographers. Bobbie Byars Lynch Collection (S-77-53-18)

Organized by Judge Millard Berry and others in 1886, Springdale Canning Company is believed to have been the first commercial cannery in Northwest Arkansas. It closed in 1903. The building was used by another cannery before becoming an ice plant. It was torn down in 2007.

” [Springdale Canning] . . . company was organized in 1886 with $3000 invested in the plant and an operating capital of about $7000. They employ over 100 people during their busy season—summer and fall. . . . Fifty cents a bushel was paid for peas in the hull and 20 cents per bushel for tomatoes. One bushel of peas in hull makes 13 pound cans. Three hands are now hired making cans. Four hands can turn out nearly 2000 cans a day. With three or four weeks experience, a country boy can make 600 cans per day—making a dollar.”

Benton County Democrat, April 23, 1887

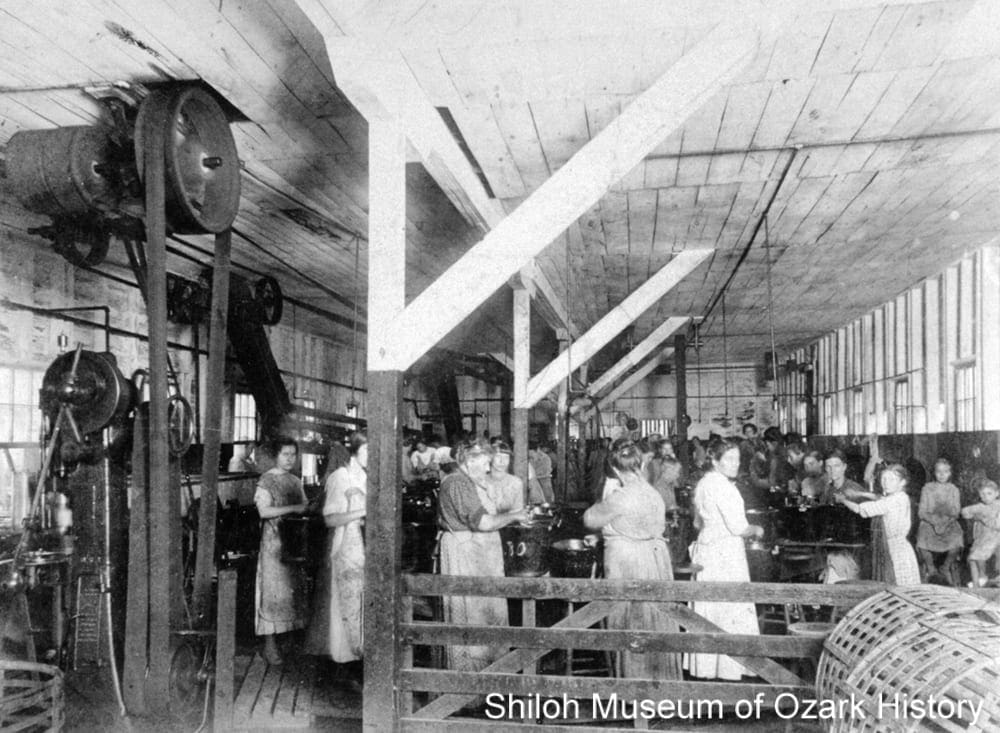

Workers likely processing tomatoes, Prairie Grove Preserves Canning Factory, Prairie Grove, late 1910s. Helen Cook Collection (S-90-20)

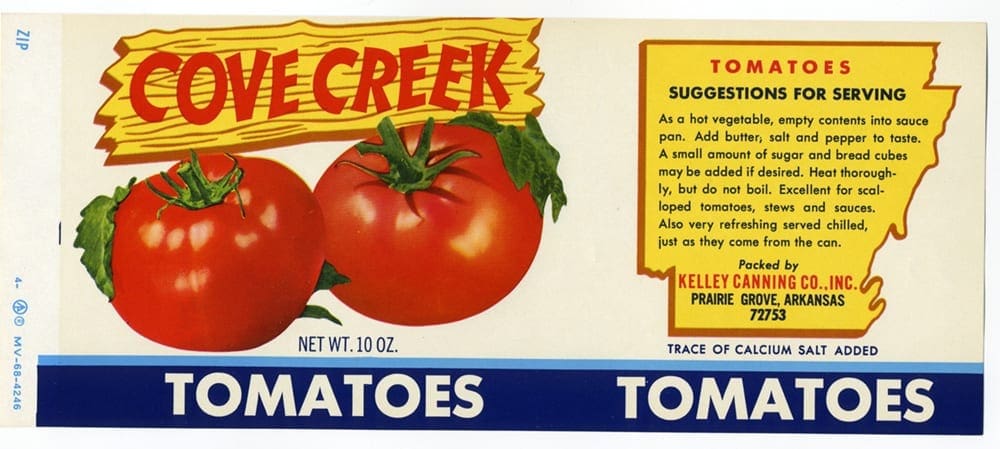

In 1903 a group of people in and around Prairie Grove agreed to give C. J. French land, materials, cash, labor, and crops in exchange for the construction of a $20,000 canning factory. In 1953 the factory became the Kelly Canning Company. As fewer local farmers grew tomatoes the company had to ship tomatoes into the area for canning. The rising cost of shipping ended the business in 1978.

“. . . [W]orkers put in 10 hour days beginning at 7 a.m. and received ten cents per hour. Peelers received three cents per bucket of peeled tomatoes. The buckets were made of red easily cleaned fiber. . . . The tomato garbage (slop) was hauled away by wagon and team, some of it being fed to the hogs. The entire factory crew numbered 114 at the checker case. Miss Effie Bain was first checker of the peeled tomatoes. They were canned in No. 2½, No. 3 and No. 10 cans which were filled by hand.”

Neva Barnes McMurry, recounting the memories of Sarah Fidler, March 1967

Washington County Observer, November 14, 1985

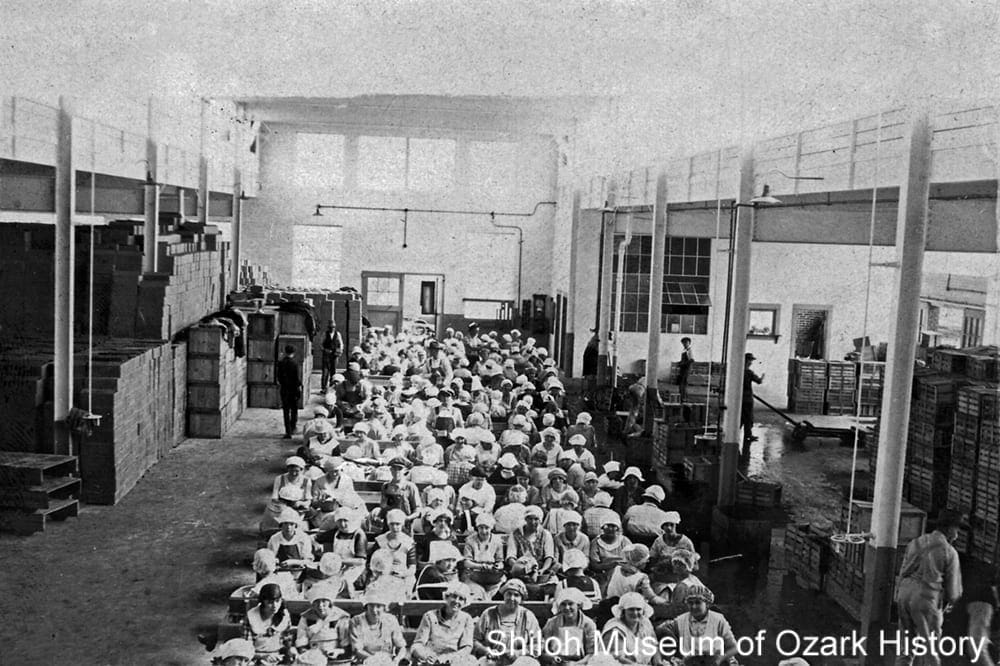

Processing grapes, Welch Grape Juice Company, Springdale, circa 1923. Joanne Paisley Collection (S-2012-63)

Springdale’s Welch Grape Juice factory was built in 1923 to take advantage of nearby grape growers. During World War II, 120 German prisoners of war worked there. At its peak, the plant could process four million cases of juice-related products yearly. The plant closed in 1978 as Welch consolidated its many operations.

[The grapes were] “ . . . weighed and inspected at the receiving platforms, whence the grapes are taken to washers and from there conveyed by machinery to stemming machines. Here the grapes are separated from the stems and dropped though aluminum pipes to aluminum stirring kettles. . . . The kettles heat the grapes and the juice is extracted by hydraulic presses. The juice flows into heating kettles and from there goes to five-gallon glass carboys [bottles] in which it is stored in different cellars. . . . [Later] the juice is siphoned out, placed in automatic filters and then goes to automatic cappers. …the juice is pasteurized and the bottles labeled, packed and shipped away.”

Springdale News, April 29, 1937

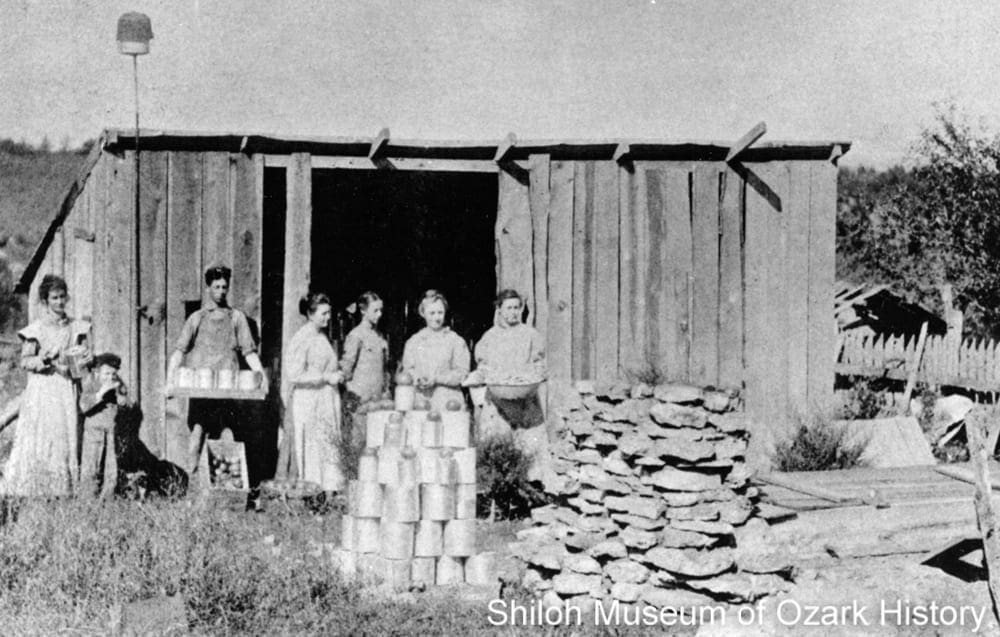

Pettigrew Canning Company workers, Pettigrew, late 1930s–early 1940s. From left: unidentified, Edna Williams Bryant, Nancy Ahart, unidentified, unidentified, and Pap Ahart. Oleta Bryant Collection (S-2008-34-4)08-34-4)

W. Fletcher Keck started the Pettigrew Canning Company (Madison County) in 1935. The cannery was a welcome source of income during the Great Depression, at a time when the local timber industry was slowing down.

“People who worked at the [Pettigrew] canning factory made fifteen cents an hour, or if you were peeling tomatoes, you were paid by the bucket. Basically women did the processing and men ran the heavy equipment. Every time a woman finished peeling a bucket of tomatoes, somebody would bring her another bucket and punch a ticket to show how many buckets she had peeled. My mother [Elva Barker Martin] was very fast with her hands, so she worked at the packing vat. She put a lump of salt in a can with the tomatoes and sent it down to the capper, where the can was sealed.”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

“When I left school, I did a lot of things. I worked out on a farm, I picked cowpeas. We would get maybe half a cent per pound. . . . Frank and Carrie Perona had a canning factory [in Tontitown]. . . . The cannery was just seasonal, but I worked most of the year for them. I did everything in that cannery. I fired the boilers. I cooked the food in the retorts. I hauled all the way to Fort Smith and Oklahoma City. We would work six days a week, ten hours a day, and at the end of the week we got a check for $6—a dollar a day.”

Floyd Maestri, 2002

Memories I Can’t Let Go Of: Life Stories from Tontitown, Arkansas, 2012

“There were several men hired by the Railroad to promote tomato factories. . . . [A] group of businessmen would put up the money as loans to local banks. The banks would then contract with local businessmen to buy the canning equipment. This would include the racks, trays, boilers, etc., as well as putting up a building. The local businessmen would then contract with area farmers to grow tomatoes and guaranteed them a buyer for their crop. The bank would also advance money to the farmers. The Railroad’s part was to send men into towns and make all of the arrangements to get these businesses started, and of course they would guarantee shipping, etc.”

Oak Leaves, Spring 1990

Some of the tomato varieties grown in Northwest Arkansas were Rutgers, Marglobe, and Baltimore. Rutgers was introduced in 1934 and boasted thick, fleshy outer and inner walls with few seeds—perfect for canning. Farmers often received seed and fertilizer from the canneries, the cost of which was deducted from the purchase price of the crop.

“Picking tomatoes was heavy, hot summer work and everybody helped pick. Crates of tomatoes were stacked high all over. . . . We all remember wagon loads of tomatoes leaving a trail of juice in the dust along the graded part of the road leading to Pettigrew [and its cannery]. . . . A wagon load of tomatoes is a very heavy load for a team of horses to pull up hill. On the steepest part of a mountain they could only pull a short distance before resting. . . . The horses would be wet with sweat and gasping for air in the summer heat. I felt sympathy for them, feeling they paid a high price in life for the little they got in return.”

Vernon Eaton

Madison County Record, May 30, 1996

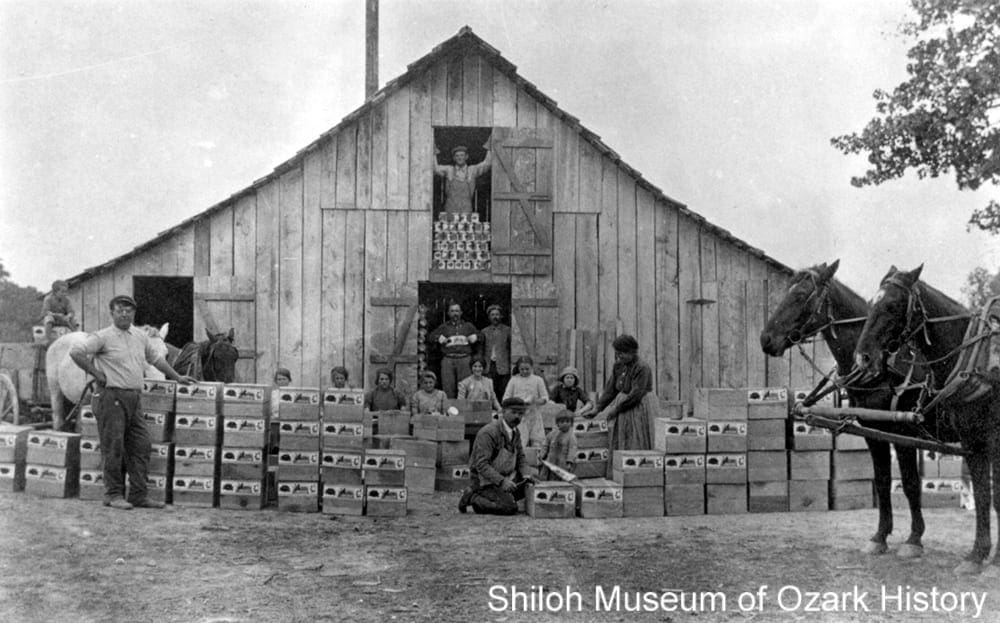

Barrett Canning Factory, Grandview (Carroll County), circa 1910. Mrs. Tracy Barrett Collection (S-90-11-105)

Tracy Barrett (holding tray in photo above) convinced his father George to build Carroll County’s first canning factory in 1910. Tracy hated farm work and saw how the hard work of farming was affecting his father’s health.

Tracy Barrett persuaded “ . . . area farmers to plant tomatoes. . . . [H]e erected a truly commercial canning factory, with his own railroad siding and his own registered label. For several harvest seasons this went full bore, giving the farmers a ready market and providing many temporary jobs as he filled one boxcar after another with canned tomatoes.”

Richard H. Barrett

Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Spring 1985

Robinson Canning Company, Siloam Springs, September 24, 1931. M. Larrick, photographer. Dr. Lloyd Warren Collection (S-92-35-24)

Owned by Burtis A. Rudolph, during Robinson Canning Company’s first year of operation in 1925 it processed twenty-five railroad carloads of tomatoes. The cannery closed in 1935 when the Federal government bought exhausted, eroded farmland for the construction of Lake Wedington. There were few viable fields left for growing vegetables.

After its closing, “The Robinson factory stood empty until it was torn down in the fall of 1937. All that remain today are some cement columns. Boys of the area used the cement water tank . . . as a swimming pond.”

History of Robinson and Kincheloe Communities, 1995

In 1925 at least two libel suits were filed against the Valley Canning Company cannery in Hindsville (Madison County), alleging its string beans failed to meet Federal food production standards.

The U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas “. . . [alleged] that the article [80 cases of canned stringless beans] had been shipped by the Valley Canning Co., from Hindsville, Ark., on or about August 28, 1925 [to Marfa, Texas]. . . . Adulteration of the article was alleged in the libels for the reason that a substance, excess water, had been mixed and packed therewith so as to reduce, lower, and injuriously affect its quality and had been substituted wholly or in part for the said article [string beans]. Adulteration for the further reason that the article consisted in whole or in part of a filthy, decomposed, and putrid vegetable substance.”

W.M. Jardine, Secretary of Agriculture

Service and Regulatory Announcements, Bureau of Chemistry, January 28, 1927

Springdale Canning Company co-owners Luther Johnson (center left) and Joe M. Steele, Springdale, September 25, 1937. William McIntosh, photographer. Philip Steele Collection (S-2005-112-6)

The above photo shows the first complete trainload of canned vegetables ever shipped by one canning factory owner in Springdale, and perhaps the first such shipment from Northwest Arkansas. Cannery co-owner Joe Steele was thirty-two years old at the time and owned or co-owned five canneries.

“Mr. Steele stated that orders enough to fill the 24 cars . . . came in last week, and enough more goods were sold to fill eight more cars, had there been time to label [the cans] and load the cars by the time for the train to leave. . . . The cans were filled with . . . turnip greens, mustard greens, spinach, green beans, and tomatoes. . . . The Springdale plant processed 3,500 cases of beans in ten hours and three of the factories, which can spinach, processed 8,000 cases per day, the latter meaning the same as two and a half cars of empty cans.”

Springdale News, September 30, 1937

1940s–1950s

Alonzo Roberts turning green beans to keep them from overheating while awaiting processing for U.S. armed forces, Springdale Canning Company, Springdale, 1943. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-569)

“For several days all of the boys at our mess had been talking about how good the canned beans have been lately. I remarked that the reason they’re so good is because they were canned in Arkansas [by Springdale Canning Company].

Pfc. John P. Woods, New Caledonia,

Springdale News, August 2, 1945

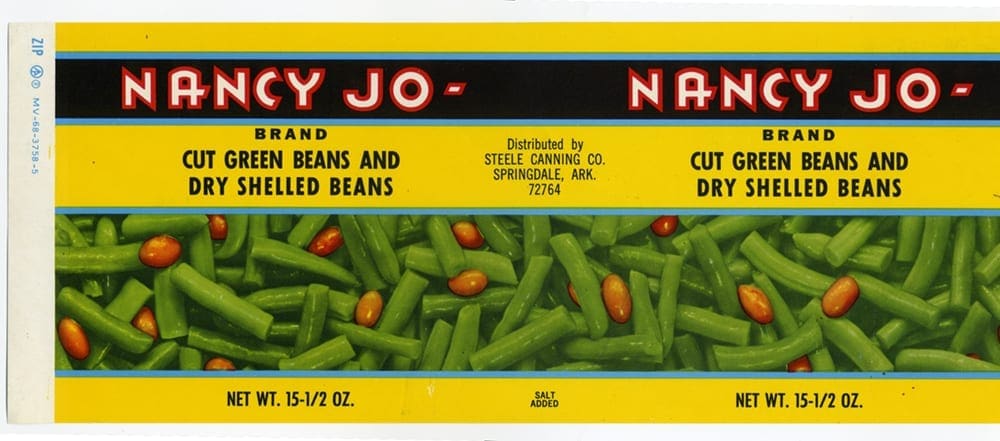

“Today I found a case of your No. 10 cans of Nancy Jo spinach right in our kitchen. Some of the soldiers probably thought I was shell-shocked the way I acted when I saw those labels. I pasted on enough of those labels one summer that I shouldn’t ever forget them. I don’t mind saying it—it was just like a letter from home.”

Lt. Edgar C. Wood, Tunisia, May 13, 1943

Steele and Springdale Canning Companies brochure, 1946

Workers picking and sorting spinach prior to its washing, Steele Canning Company, Springdale, circa 1948. (S-90-11-115)

“Only the choicest spinach is used which is grown in fields under natural weather conditions, harmonizing with the fine composition of the soil to produce the very finest flavored spinach. Careful hand-picked operations permit delivery of only the choicest leaves to the washers and a multitude of washing operations, many of them we have pioneered, assuring a product for the consumer’s table which is entirely free from grit.”

Steele and Springdale Canning Companies brochure, about 1948

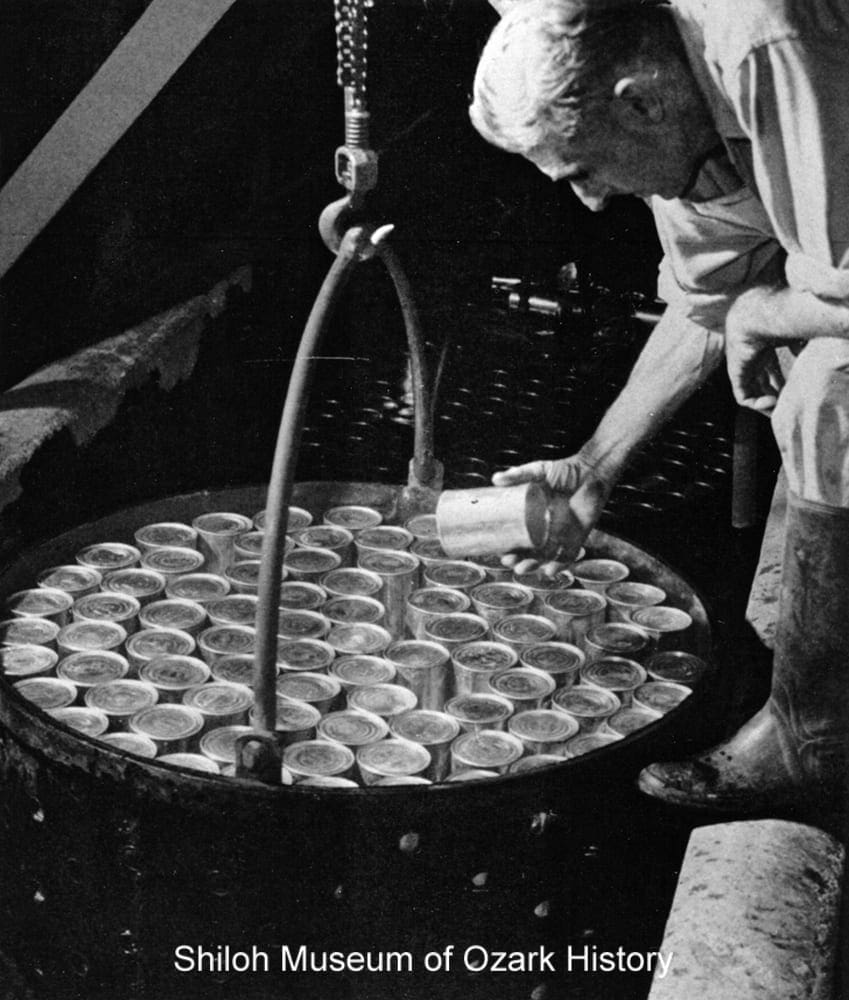

In Steele Canning Company’s cannery, roughly 360 cans would be placed into a large metal basket for cooking. Once cooked, the cans were cooled with flowing water. Smaller operations skipped this step, letting their cans cool in the open air.

“. . . [the] cooling vat with [its] continuous flow of water. . . produces a quick chilled can resulting in a better vacuum. This quick chilling also produces accurate favoring because of temperature control of the finished canned product.”

Steele and Springdale Canning Companies brochure, about 1948

Canning Center, Springdale High School, Springdale, 1943. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-568)

Springdale High School’s Canning Center was one of twenty such facilities throughout Arkansas, furnished and controlled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to aid home canners in the proper methods of food preservation.

The cannery had “. . . three large thirty-three-quart capacity retorts, a small pressure cooker, hot water cookers, three sealers, a dehydrator, bottle cappers, pre-cookers and other minor equipment. . . . The cannery is located in two north basement rooms of the school building and will remain a permanent feature of the school, being open for housewives and home canners of Springdale and neighboring territory . . .”

Springdale News, July 8, 1943

Welch Grape Juice Company, Springdale, June 1944. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-336) Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-336)

An existing railroad spur was extended from the nearby ice plant to serve Springdale’s Welch Grape Juice factory, which relied on the railroad to distribute their products.

“. . . this region thus possesses some focal transportation characteristics, a fact of great value. To the canning industry this has meant that the canned product can be moved out readily. It has also meant that fruits and vegetables destined for the canneries can move in, not only from immediately adjacent areas, but also from contiguous regions north, west, and south.”

Irene A. Moke

Economic Geography, April 1952

Steele Canning Company trucks, Springdale, 1940s–1950s. V. D. McRoberts, photographer. Philip Steele Collection (S-2005-112-5)

Steele Canning Company was started in the Steele community near Tontitown in 1924, when Joe M. Steele needed money to attend college. His business later grew to be the largest canning operation in Washington County.

“The rural and small-urban economy has developed amazingly [in the past ten to fifteen years]. The business districts of the towns are spreading, the highway fairly hums with traffic, and anyone who knew the rather somnolent region in 1935 would scarcely recognize it now. No attempt is made here to credit the canning business alone with this progress. However, there is no doubt that the canneries play a leading role in the economy, and perform a most valuable function for the farm areas of this region and of other districts outside of northwestern Arkansas.”

Irene A. Moke

Economic Geography, April 1952

1960s–1980s

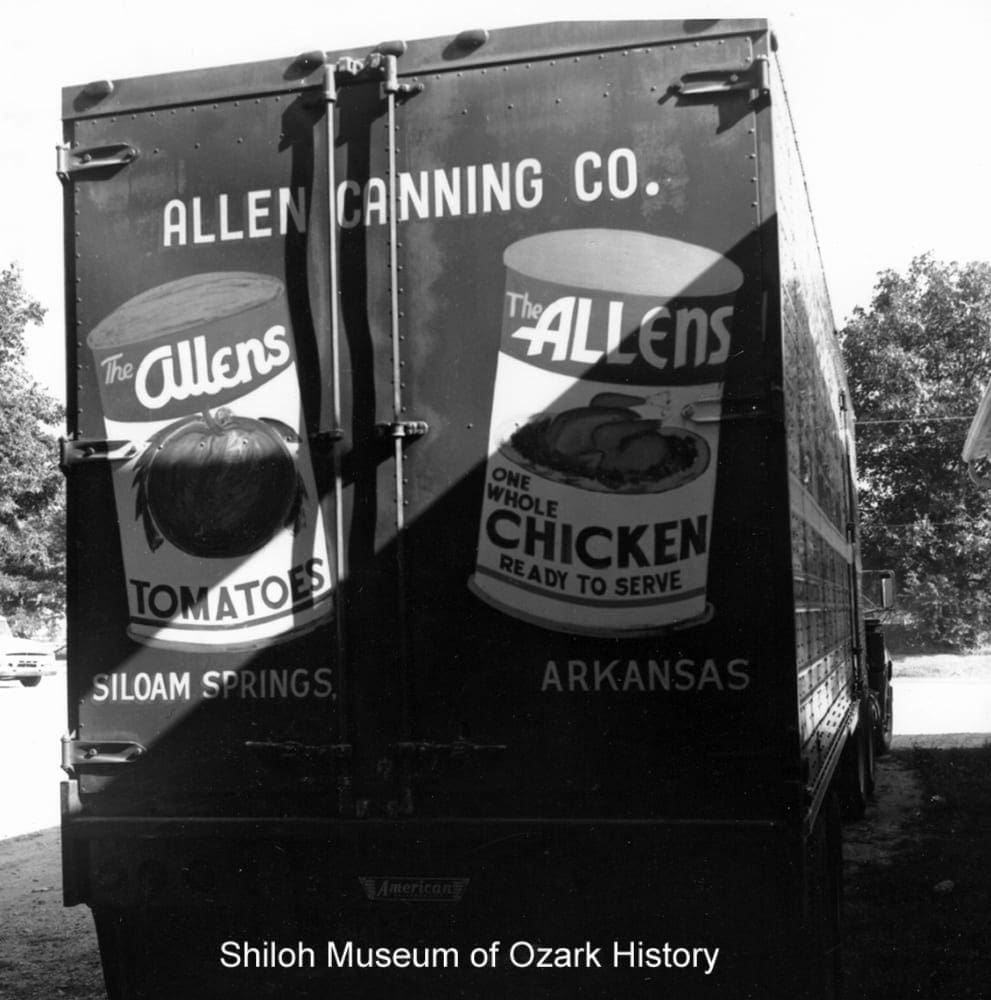

Allen Canning Company truck, Siloam Springs, July 23, 1964. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-1472)

Earl Allen started Allen Canning Company in Siloam Springs in 1926. In his first year he had canned 4,000 cases of tomatoes. A family-owned business, in 1988 Allen’s had fourteen plants and distribution centers in five states and offered over eighty-five different products.

Filling cans with spinach, Steele Canning Company, Springdale, May 1969. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-2074)

“Nothing was screened in [at the Georgetown Cannery near Japton]; flies were very thick, as the waste was just hosed off the floors and tables into a ditch or creek. . . . the women took their children with them to work. . . . My mother would put my younger sister and I on a quilt, then stretch a tent-like cover of mosquito netting up over us to keep the flies off. Most babies just lay in the flies, crawling in the eyes and mouths, no wonder so many had dysentery. Very few workers washed their hands after going to the toilet or diapering a baby. I guess seeing so much unsanitary conditions as a kid is the reason I didn’t want to eat commercially canned food.”

Lena Davis Law, August 1997

Madison County Musings, Fall 2006

“At the end of the day [at John Goucher’s cannery in Madison County], the canning factory was cleaned using scalding water. . . . the factory was sealed overhead with aluminum, the side walls were covered with linoleum, and the floors were concrete so that everything could be washed down. . . . they never had any trouble with contamination. Mr. Jones, who was the inspector that came around to check on the canning process, usually bought five cases of tomatoes each year . . . for his own use after he had watched the process and saw how clean the factory was.”

Joy Russell recounting the history of John Goucher

Fading Memories III: Stories of Madison County People and Places, 1999

Testing lab, Allen Canning Company, Siloam Springs, September 2, 1967. With Deward Bishop (right). Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-1547)

“We have quality control labs in every [Allen] plant and they check the quality on every lot of merchandise that is packed. …When the products are tested, the lab technicians look for factors that affect weight, color, characteristic or texture and they look for the absence of defects. The samples are also analyzed to test the salt content. The grading or sizing of each lot is also double checked to insure the count contained in each can size of the products is accurate.”

Inside Arkansas, Fall 1980

Steele Canning Company products, Springdale, April 3, 1961. Ray Watson, photographer. Marie Steele Collection (S-77-15-14)

“Back in 1924, when [Steele Canning Company] started, we bought the cans in the bulk, in [railroad] car load lots, unloaded them, and transported them, ricked in rows on hay frames on wagons from Johnson to Steele [Community]. There were four loads to a car, and it took one day and night and all the next day to unload the cars, and haul the cans to the plant. . . . Today the cans are bought by the car load in boxed paper bags which hold 210 No. 2 cans. Unloaded, stacked and as needed they are emptied into filling machines.”

Joe M. Steele

Springdale News, August 8, 1945

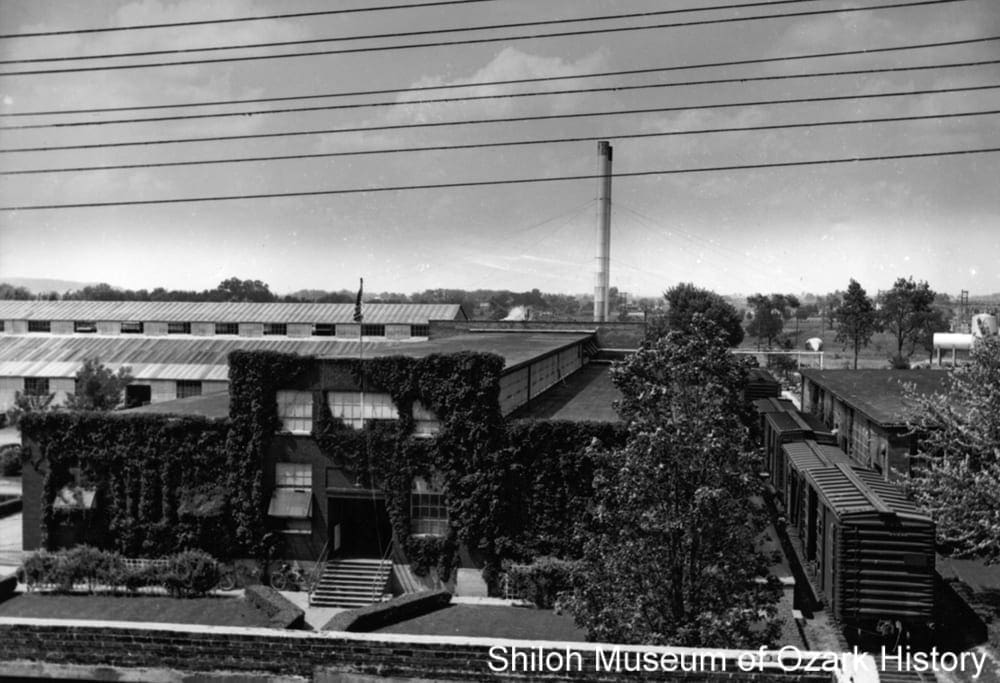

Heekin Can Company, Springdale, February 10, 1982. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-86-31-16)

Heekin Can Company opened a manufacturing plant in Springdale in 1949 to be close to the major canneries. In 1986 Heekin shipped about 430 million cans. Ball Corporation acquired Heekin in 1993. The Springdale plant produced containers for Southern and Midwestern customers until its closing in 2020.

“The pieces of tin . . . are placed in the feed slots on this body maker machine. From there a button is pushed and the body takes off. It is notched, folded, fluxed, expanded, bumped, warmed, soldered, heated again, wiped and cooled. When it gets through with all of this you have a tin can . . . That is, you have everything except the top and bottom. All this folding, bumping, fluxing, etc., takes about half a second.”

Springdale News, June 1, 1949

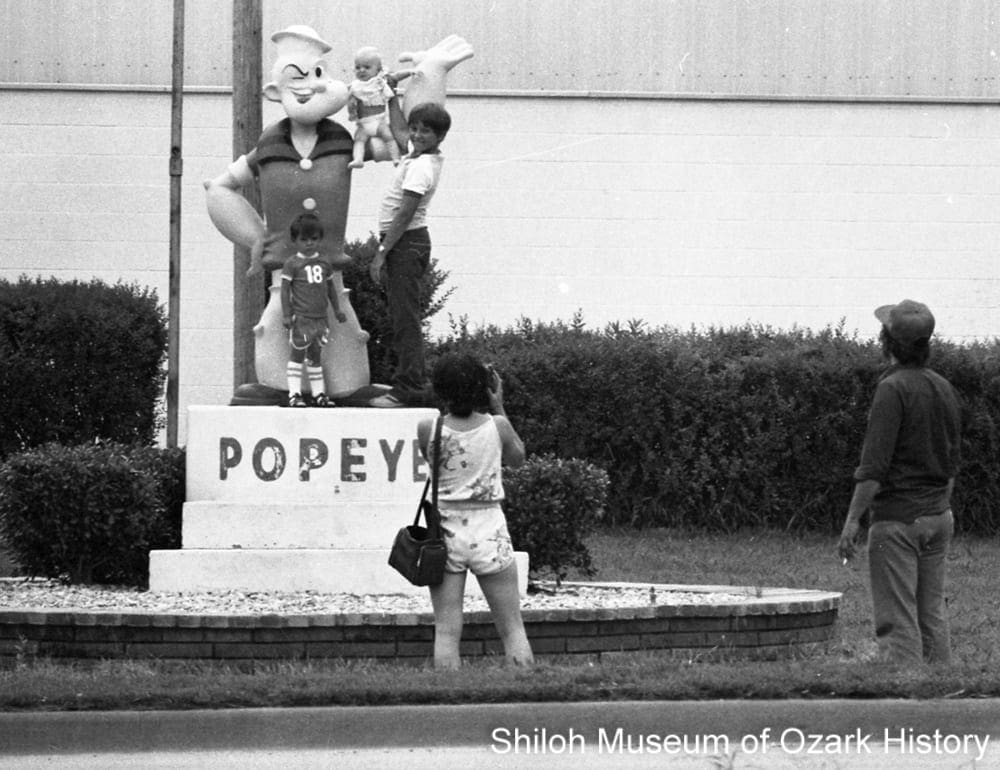

Children pose with the Popeye statue, Allen Canning Company, Springdale, June 18, 1980. Mark Neil, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 6-18-1980)

Allen Canning Company bought the old Steele Canning Company building and the Popeye brand in 1978. The plant closed in 2002 because the property was landlocked; there wasn’t room for growth.

“ . . . [Popeye] caught on with millions of kids and soon became a national hero, much to the delight of spinach marketers. Spinach sales jumped 33 per cent and the vegetable has since enjoyed increasing popularity. . . . The first Popeye spinach label [from Steele Canning] will offer a three-piece Melmac dinnerware set featuring Popeye characters, which will be offered for $2 and [two labels].”

Springdale News, December 6, 1965

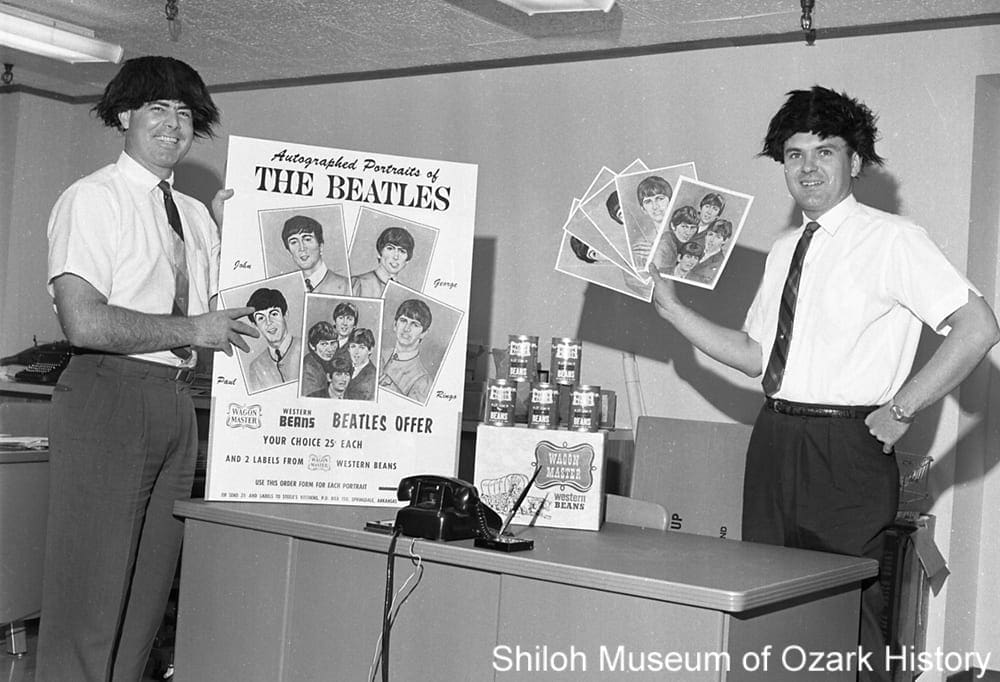

Beatles promotion for Wagon Master beans, Steele Canning Company, Springdale, August 1964. Art Pruett (left) and Phillip Steele. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 8/1964 #3)

Marketers used celebrities to increase brand popularity and consumer purchases.

“The beans were ‘terrific’ and the Beatles were popular, but the campaign didn’t save Wagon Master beans, which died a slow death . . . Consumers wouldn’t buy anything but pork and beans or chili beans.”

Philip Steele

Springdale News, April 10, 1994

A Day in the Life of a Green Bean

Hey, kids! I’m Snappy, a green bean grown on a farm right here in Northwest Arkansas. Did you know that during World War II the Springdale Canning Company packed 12,000 cases of green beans each summer day? That’s a lot of beans! Come with me on a tour of the process from start to finish.

Hey, kids! I’m Snappy, a green bean grown on a farm right here in Northwest Arkansas. Did you know that during World War II the Springdale Canning Company packed 12,000 cases of green beans each summer day? That’s a lot of beans! Come with me on a tour of the process from start to finish.

These photos were all taken at the Springdale Canning Company in 1943. Howard Clark, photographer/Caroline Price Clark Collection.

2002-72-574

1. It all starts here, at the cannery, where farmers unload their truckloads of beans. (S-2002-72-574)

2002-72-578

2. The green beans are put into bushel baskets and carried to one of ten snipping machines. Each machine removes the ends of the beans, about 1,800 to 2,000 pounds every hour. (S-2002-72-578)

2002-72-566

3. Then the beans are inspected by teams of women who make sure each one is snipped. They also remove bad beans. The beans move from one conveyor belt to another. (S-2002-72-566)

2002-72-565

4. Next the beans are washed and cut into 1½-inch pieces. From here on out the beans are processed entirely by machine. (S-2002-72-565)

2002-72-576

5. The cut beans are washed again and again. A sieve shakes out hulls and other waste before the beans move up the conveyer to the blancher, where the beans are cooked in hot water for a few minutes. Blanching helps preserve color. (S-2002-72-576)

2002-72-575

6. The beans go to the filling room where they are placed in cans. A salt tablet is added as a preservative and the cans are filled with water. A machine shakes each can gently to level its contents. From left: Vernal Thomas and Elvin Douthit. (S-2002-72-575)

2002-72-567

7. The closing machine seals lids onto filled cans. The machine can handle 252 cans a minute. That’s 151,200 cans during a 10-hour shift! The man in overalls is Vasco Cude. (S-2002-72-57)

2002-72-570

8. Each metal basket is filled with 360 cans and is placed in one of 10 retorts (pressure cookers) which cook foods quickly. After cooking, the canned beans are chilled in a water bath to help maintain their flavor. From left: Henry Jones and Thurmond Claypool. (S-2002-72-570)

2002-72-579

9. Next, labels are placed on the cans which are then packed for shipping. During the war the cans were a dull olive color. This “camouflage” kept enemy airmen from spotting shiny metal cans and figuring out troop movement. From left: Minnie Smith, Ed Wilkly, Margaret Beasley, and Audrey Ingram. (S-2002-72-579)

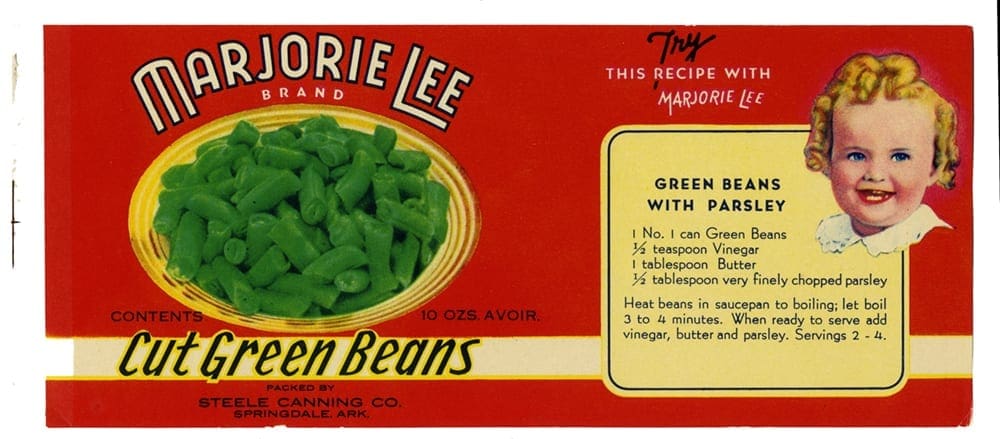

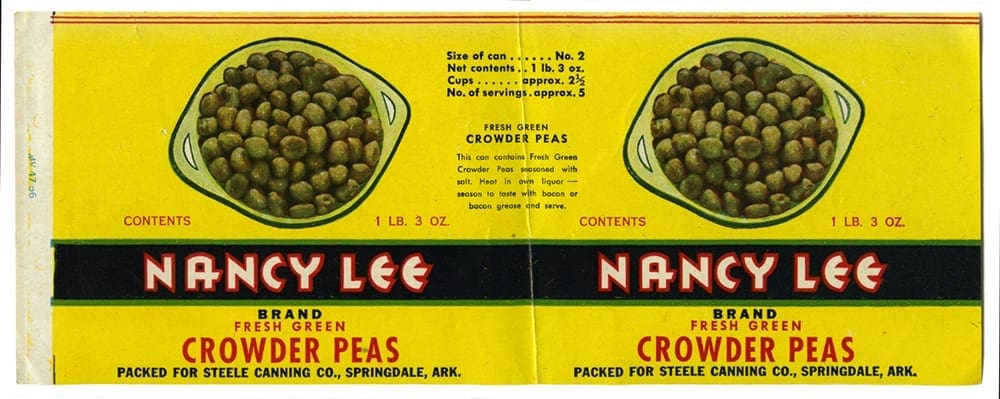

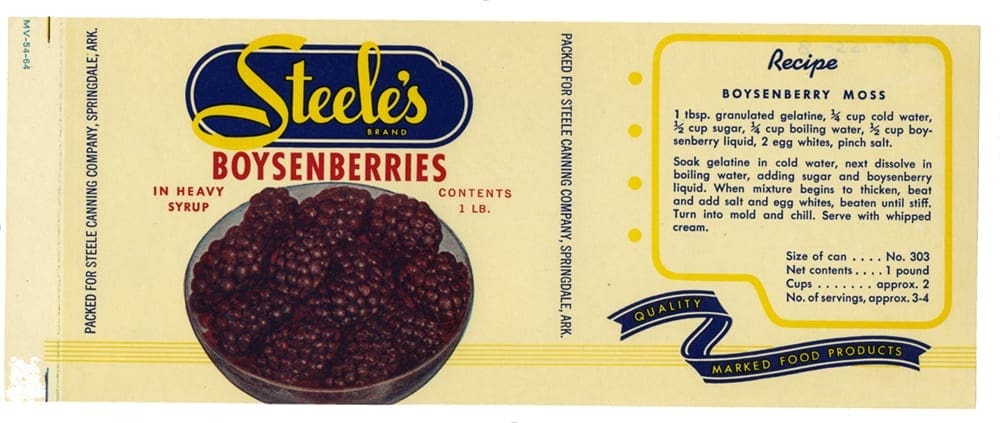

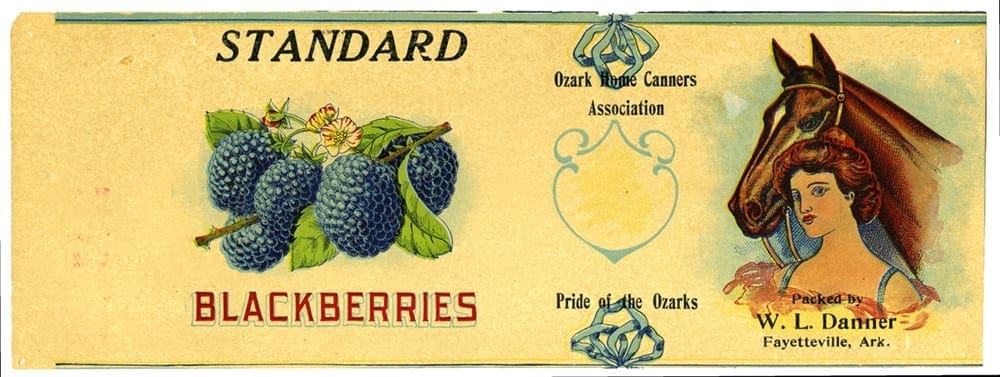

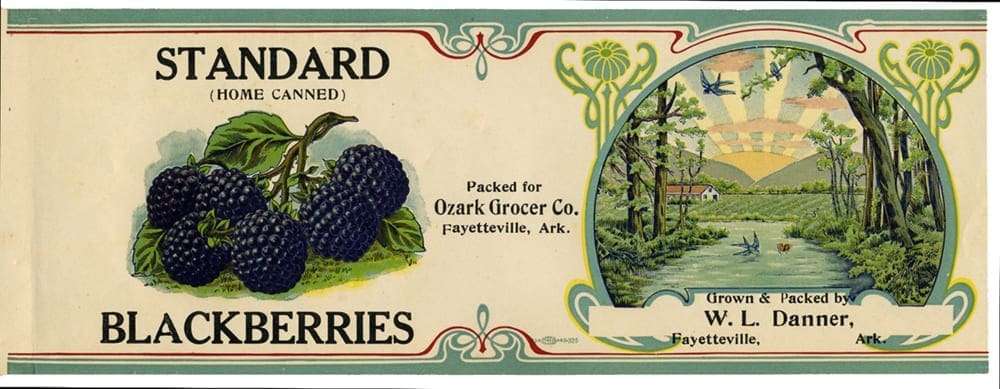

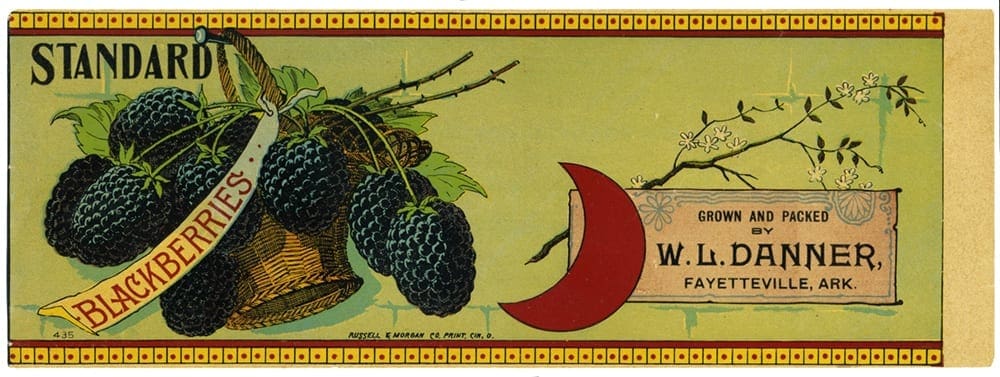

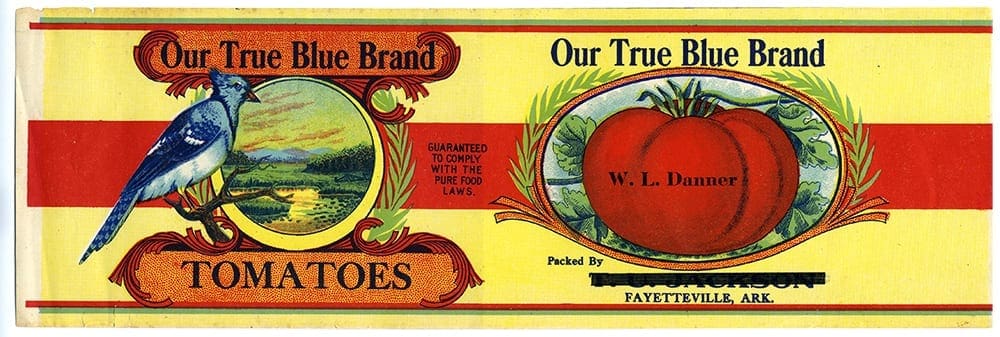

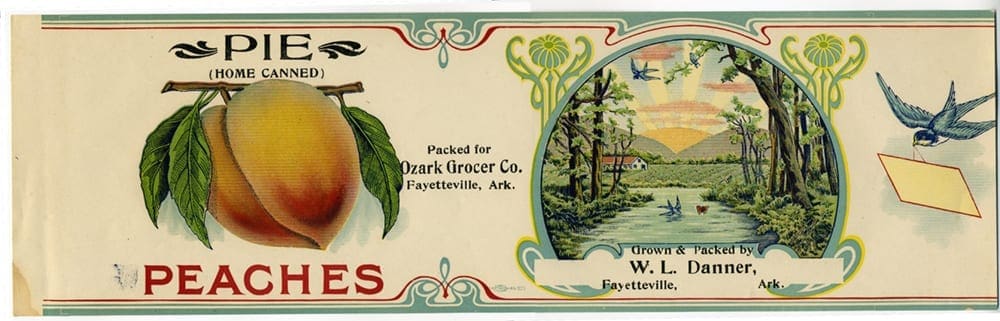

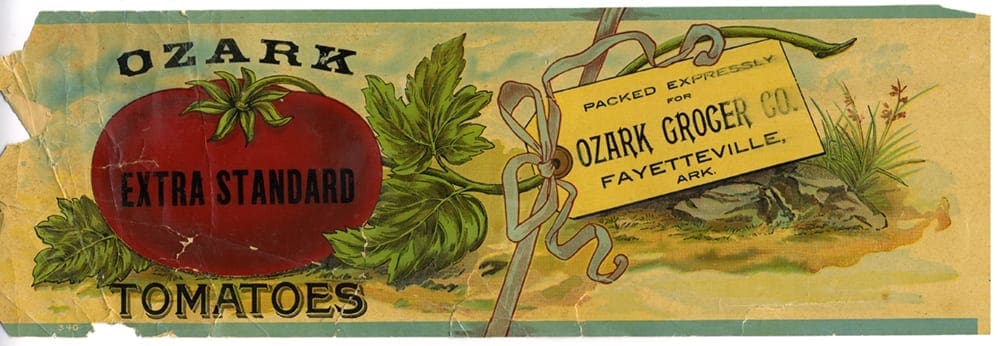

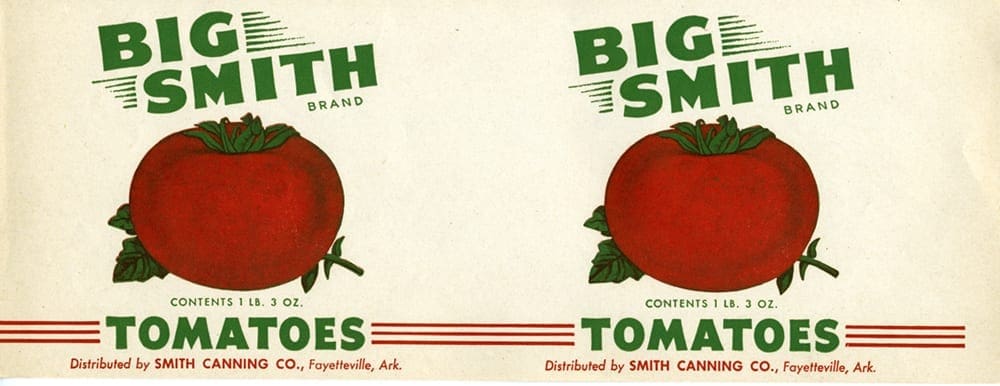

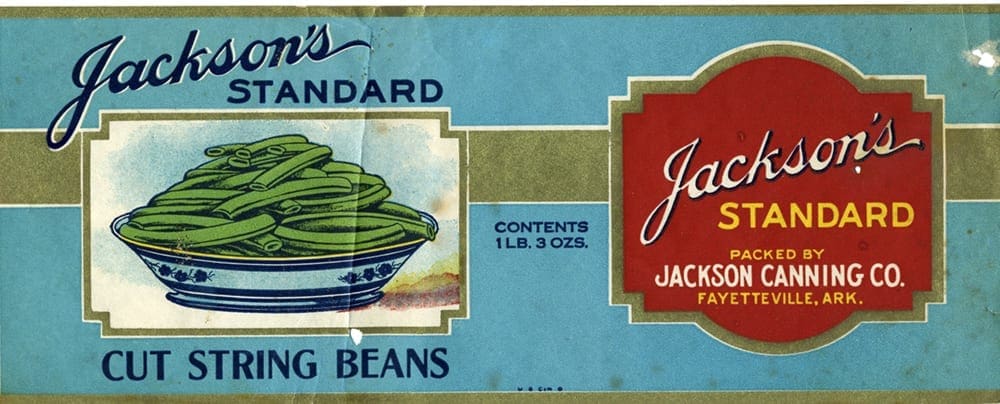

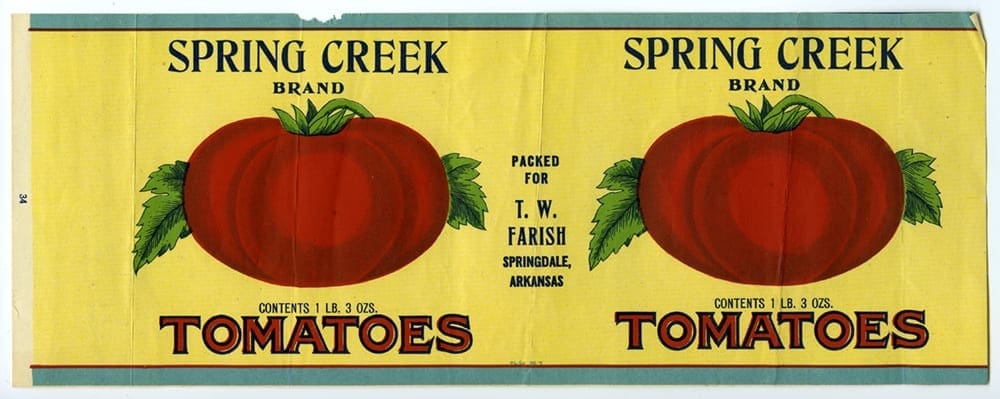

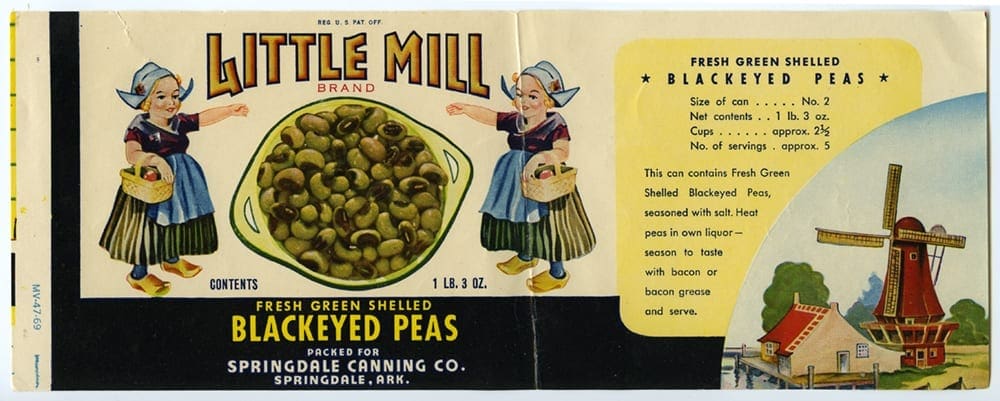

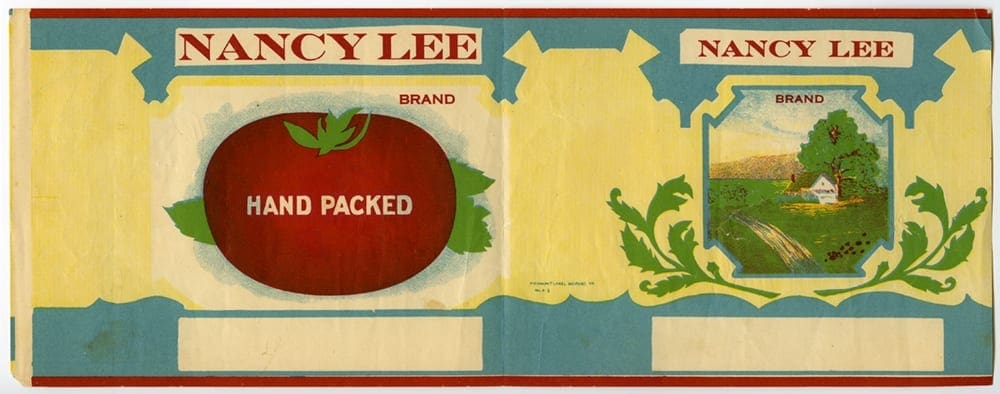

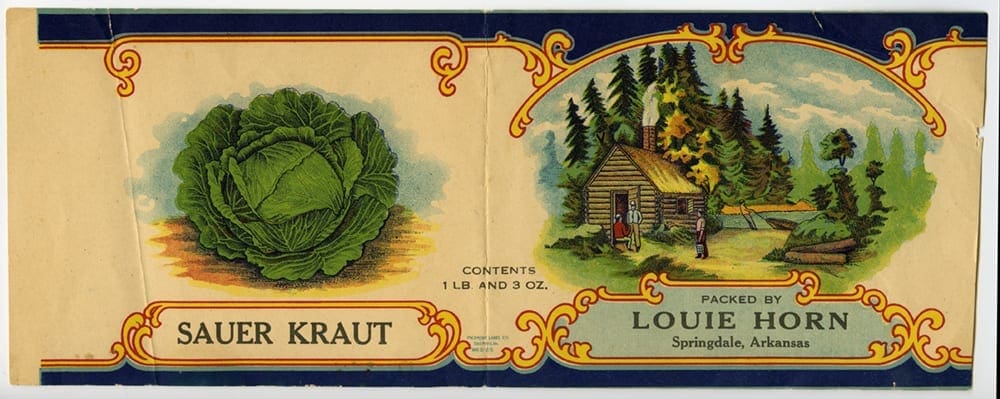

Canning Label Gallery

Listen to the Past

Click on the names below to hear stories about the local canning industry from folks who were involved in it. Some memories are told by the people themselves or by family members. Other recordings are accounts of canning memories, retold and read by Shiloh Museum staff and volunteers.

Otto Bennett

Velma Bennett

Nathan Bowerman

Lloyd Bowling

Charles Brink

Kenny Bryant

Oleta Williams Bryant

Coy Collins

Doris Denzer

Jake Edens

Sophia Estes

Jean Gray

Edna Barnes Henderson

Dan Hendricks

James R. McNally

Jeanie Fultz Miller

Jerry Putman

Waneta Smith Redfern

Ginger Greathouse Roces

Sue Brashears Springer

Margaret Disney Stamps

Truman Stamps

Mary Maestri Vaughan

Credits

Arkansas Gazette. “Allen cans veggies, Popeye spinach.” 3-8-1989.

———. “Madison Tomato Crop Valued at Around $600,000.” 8-4-1939.

Barnes, Guy. “Steele Family Marks 65th Year in Food Processing Business.” Springdale News, 12-17-1989.

Barrett, Richard H. “A Chronicle of Carroll County Barretts.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly Vol. XXXI, No. 1 (Spring 1985).

Benton County Pioneer. “News from Benton County Democrat, Apr. 23, 1887, J.M. Thompson, Publ.” Vol. 4, No. 3 (March 1959).

Caraway, Steve. “Canning Plant to Close.” Springdale News, 9-19-2002.

Eaton, Vernon. “Remembering the Ozarks: Green Beans.” Madison County Record, 8-12-1999.

———. “Remembering the Ozarks: The Tomato Field.” Madison County Record, 5-30-1996.

Hendricks, Dan. Interview by Marie Demeroukas, Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. 3-8-1913.

History of Robinson and Kincheloe Communities, Yell Precinct, Benton County, Arkansas, Robinson Historical Committee: Siloam Springs, 1995.

Inside Arkansas. “Allen Tradition is Built on Can.” Vol. 16, No. 3 (Fall 1980).

Jardine, W. M. Service and Regulatory Announcements, Bureau of Chemistry, Supplement. United States Department of Agriculture, 1-28-1927. http://mdot.nlm.nih.gov/fdanj/bitstream/123456789/46929/4/fdnj14952.pdf (accessed 4/2013; no longer available online).

Law, Lena Davis. “More Cannery Information.” Madison County Musings Vol. XXV, No. 3 (Fall 2006).

Lucas, Margaret M. Ozark Canners and Freezers Association Progress Report. Ozark Canners and Freezers Association, 1963.

Lynch, Bobbie Byars. “The Springdale Canning Industry.” Shiloh Springdale 1878-1978. Springdale [Arkansas] Centennial Committee, 1978.

Martin, Wayne. Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World. Shiloh Museum of Ozark History: Springdale, Arkansas, 2010.

May, Patricia. “From Popeye to the Beatles: Steele Adventures in Food.” Springdale News, 4-10-1994.

McMurry, Neva Barnes. “Factory Workers Remember…” Washington County Observer, 11-14-1985.

Moke, Irene A. “Canning in Northwest Arkansas: Springdale, Arkansas.” Economic Geography Vol. 28, No. 2 (April 1952).

Morelock, T. E. “Washington County Canneries Then and Now.” Flashback (Washington County Historical Society) Vol. 55, No. 3 (Summer 2005).

Oak Leaves. “Canning, Refrigerator Cars, and Fresh Produce.” Missouri and Arkansas Railroad Research Group, Spring 1990.

Prairie Grove Canning Factory Subscription List, 11-24-1903. Shiloh Museum Collection, Manuscript 42, Box 4A, Folder 23 (S-90-67-4).

Rothrock, Thomas. “The Judge Berry Story.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. XV, No. 2 (Summer 1956).

Russell, Joy. “John Goucher.” Fading Memories III: Stories of Madison County People and Places, Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society, 1999.

Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. “What’s in Season from the Garden State: The Historic Rutgers Tomato Gets Re-invented in University’s 250th Anniversary Year” http://www.njfarmfresh.rutgers.edu/WhatabouttheRutgersTomato.htm (accessed 10-23-2020).

Shiloh Museum research files. “The Steele’s 65 Years in the Food Industry, From Canned Tomatoes to Microwave Desserts,” unknown source and author, 12-4-1989.

Siloam Springs Herald Democrat. “Allen Canning Co. continues to grow.” 6-28-1987.

Silva, Rachel. “Walks Through History: Historic Downtown Prairie Grove,” Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=145012 (accessed 10-23-2020)

Springdale News. “‘Springdalia’ Manages for Preview Tour of New Factory…” 6-1-1949.

———. “Almost-Empty Welch Plant Reminder of Another Time.” 6-22-1986.

———. “Canner Ships Train Load of Products.” 9-30-1937.

———. “Canning Industry Has Close Ties to Agriculture.” 2-23-1982.

———. “Canning One of Sections [sic] Important Industries.” 4-29-1937.

———. “Formal Opening of Canning Center to be Held July 14.” 7-8-1943.

———. “Grape Juice and Wine Are Local Products.” 4-29-1937.

———.. “Heekin Can Company Formally Opened With Ceremonies Here Saturday.” 6-6-1949.

———. “Heekin Produces Millions of Cans.” Springdale News, 6-22-1986.

———. “Many Visitors Expected for Award Ceremony.” 8-2-1945.

———. “One of the ‘Big Deals’…” 6-1-1949.

———. “Prison Labor Necessary Says Welch Head.” Springdale News, 11-16-1944.

———. “Springdale Grew Up With the Food Processing.” 4-21-1985.

———. “Steele Canning Co. Gets Help of Beatles in Promoting Beans.” 8-26-1964.

———. “Steele Canning Co. Largest in Arkansas.” 11-30-1962.

———. “Steele Canning Now Has Popeye to Sell Its Spinach.” 12-6-1965.

———. “Tin Cans Hard to Handle in Early Days.” 8-2-1945.

———. “Tour of Plant Sees Beans Off to Armed Forces.” 8-2-1945.

———. “When History Was Made in Springdale.” 10-21-1937.

———.“The Springdale Canning Co. was organized…”5-15-1908.

Steele Canning Company and Springdale Canning Co. brochures, 1946 and circa 1948.

Swanson, Christie. “Allens: 84 Years and Counting.” Northwest Arkansas Newspapers, 10-3-2010.

Van Buskirk, Kathleen. “When the Tomato Was Queen.” Ozarks Mountaineer Vol. 26, No. 3 (April 1978).

Young, Susan, ed. Memories I Can’t Let Go Of: Life Stories from Tontitown, Arkansas. Farther Along Books: Fayetteville, Arkansas, 2012.