Good Eats

Online Exhibit

Community fundraising dinner at Elm Springs, 1952. Identified in the photo, from right: Sue McCamey, Goldie Routh, Ronnie Routh, Nolan McCamey, Tom Bain. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection/McRoberts, photographer (S-85-20-64)

In the early 1800s folks living in Northwest Arkansas produced and prepared nearly all of their own food. Settlers hunted game animals like deer and turkey, gathered wild fruits and honey, raised chickens and pigs, and grew such vegetables as corn and greens for the family table. Food preparation was an all-day event over a fire. There wasn’t a lot of variety in the homesteader’s diet, especially in wintertime. The “three M’s” in the Ozarks were meat, meal (corn meal), and molasses.

During the 1870s G. B. Jones made “maple sugar cakes.” A camp was set up near a stand of sugar maple trees on the family homestead west of Sulphur Springs. The sap was collected in early spring and boiled down in a big iron kettle until thick, then poured into molds to cool. Most of the finished cakes were taken to Neosho, Missouri, and sold. But a couple of the nicely browned cakes found their way into Jones’ pocket as a treat for his girlfriend.

With large food processors such as Pillsbury and Campbell’s soups beginning to produce quality, low-cost products, by 1900 half of the food eaten by most Americans came from the store. Further time-savers were soon introduced including self-service grocery stores, quick-frozen foods, packaged mixes, and frozen dinners. Eating out became popular as well. As roads opened up it became easier to ship luxury goods such as sugar and coffee to the frontier. Convenience items like tinned food began arriving mid century as canning technology improved. Further variety was possible in 1881 when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad began steaming through the Ozarks. Refrigerated railroad cars allowed perishable meat, fruits, and vegetables to be shipped nationwide. The rise of convenience food meant that traditional foodways declined. By the 1970s local newspapers were featuring articles about old-timers making apple butter or molasses the old-fashioned way. Preserving food for home use was no longer commonplace.

Today we purchase “home-cooked” meals in grocery stores, have pizzas delivered, and eat fast food in our cars. But the popularity of home cooking is increasing. Julia Child helped start the trend in the 1960s with her cooking show, “The French Chef.” Now there are many food-related magazines, television shows, and specialty stores to tempt our taste buds. Americans are rediscovering good food.

Coming Together

Think food is used only to nourish our bodies? Think again! We use food to celebrate, to stereotype people, to express love or compassion, to treat ourselves, to compete or make money, to remember our roots, to garner compliments, and to come together as a community. Our tastes in food have changed over time depending on where we live, what we can afford, and what’s in fashion.

Church members often gathered for “dinners on the ground.” Blankets were laid on the grass and then piled with a bounty of delicious foods. Lucile Dees McVay attended such dinners during the late 1920s and 1930s at the annual Decoration Day at Wedington Cemetery. Every woman brought her specialty, whether it was homemade bread, deviled eggs, or candied sweet potatoes. Young Lucile waited patiently by her mother’s salmon cakes until the blessing was said–then she helped herself! Canned salmon was so expensive that these treats were rarely made at home.

There’s something about food that has made us come together over the years. Neighbors gathered for community events such as house raisings, funerals, and school functions. During John Quincy Wolf’s youth in the 1870s Ozarks, women came together to prepare food for the men building a house. When the dinner horn was sounded promptly at noon everyone came running to partake of the fried ham, preserves, pumpkin pie, hog jowls, biscuits and cornbread, cabbage, sausage, turnips, coffee, and greens.

Families gathered for celebrations such as holidays, birthdays, and weddings. When Wayman Hogue was growing up in the late 1800s, a wedding was held at his home in the Ozarks. A dozen chickens were fattened with corn and lots of cakes, custards, pies, and light [white] bread were made. Tables placed end-to-end in the yard held three boiled hams. The hams’ skin had been removed and large round dots of black pepper added as decoration. Coffee was expensive so sassafras tea was served.

Picnics were fun occasions for friends and family. Betty Greathouse of the Greathouse Springs community southwest of Springdale liked having big picnics in her yard. Sawhorses were placed under the old sycamore tree and outfitted with wide boards and overlapping tablecloths. Family members fried chicken and guests brought covered dishes of food. One of the community elders said the blessing, “usually profound and well spoken.”

Tidbits

Members of the Springdale Women’s Civic Club, February 1953. McRoberts, photographer. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-77-9-22)

Every region of the country has dishes that it’s known for. When Charles Morrow Wilson grew up in Fayetteville in the early 1900s, typical Ozark fare included Johnny cakes, home-cured pork, Injun spareribs (a stew made with salt pork, sweet potatoes, green peppers, and corn), sweet potato puddings, hog jowls with cowpeas, and turnip greens with “pot likker,” the juice left behind after the greens and salt porkwere cooked in water.

During Wayman Hogue’s childhood in the Ozarks, “old man Adams” was the local barbeque expert. Families contributed sheep, goats, hogs, and calves to the annual Fourth of July celebration. Ditches were dug about 20 feet long and filled with oak and hickory. The evening before the big day Adams and his crew hung the carcasses from long poles and began cooking the meat.

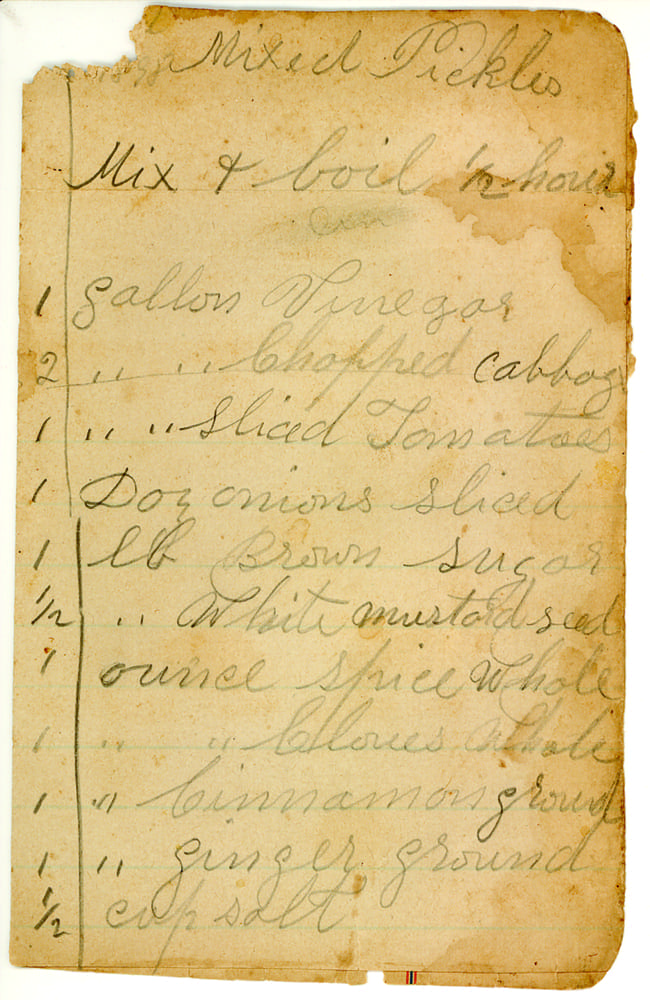

Cooking techniques and recipes were often passed from mother to daughter. In the 1910s county extension offices formed to bring “practical demonstrations” in agriculture and home economics to rural communities. Home Demonstration clubs hosted university specialists who taught scientific canning techniques, nutrition, and other homemaking skills. Canned goods not only provided food for the family, it was a good way to earn extra income.

Food was used for charitable purposes such as raising money for schools and community buildings. At box suppers and pie suppers men vied with one another to bid on the food prepared by the prettiest girl or the best cook. Bringing gifts of food to a new or struggling family was common. In Alpena a “pounding” was held for the preacher and his family. Church members brought eggs, fruit, coffee, canned goods, garden produce, sugar—whatever they wished—often in one-pound amounts.

Food can identify people in many ways. In Tontitown, the community’s early Italian roots are proudly expressed in the spaghetti served at the annual Grape Festival. But food is offensively used by some to stereotype people, such as linking traditional Ozarkers to possum or African Americans to watermelon.

Community fundraising dinner at Elm Springs, 1952. Identified in the photo, from right: Sue McCamey, Goldie Routh, Ronnie Routh, Nolan McCamey, Tom Bain. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection/McRoberts, photographer (S-85-20-64)

In the early 1800s folks living in Northwest Arkansas produced and prepared nearly all of their own food. Settlers hunted game animals like deer and turkey, gathered wild fruits and honey, raised chickens and pigs, and grew such vegetables as corn and greens for the family table. Food preparation was an all-day event over a fire. There wasn’t a lot of variety in the homesteader’s diet, especially in wintertime. The “three M’s” in the Ozarks were meat, meal (corn meal), and molasses.

During the 1870s G.B. Jones made “maple sugar cakes.” A camp was set up near a stand of sugar maple trees on the family homestead west of Sulphur Springs. The sap was collected in early spring and boiled down in a big iron kettle until thick, then poured into molds to cool. Most of the finished cakes were taken to Neosho, Missouri, and sold. But a couple of the nicely browned cakes found their way into Jones’ pocket as a treat for his girlfriend.

With large food processors such as Pillsbury and Campbell’s soups beginning to produce quality, low-cost products, by 1900 half of the food eaten by most Americans came from the store. Further time-savers were soon introduced including self-service grocery stores, quick-frozen foods, packaged mixes, and frozen dinners. Eating out became popular as well. As roads opened up it became easier to ship luxury goods such as sugar and coffee to the frontier. Convenience items like tinned food began arriving mid century as canning technology improved. Further variety was possible in 1881 when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad began steaming through the Ozarks. Refrigerated railroad cars allowed perishable meat, fruits, and vegetables to be shipped nationwide. The rise of convenience food meant that traditional foodways declined. By the 1970s local newspapers were featuring articles about old-timers making apple butter or molasses the old-fashioned way. Preserving food for home use was no longer commonplace.

Today we purchase “home-cooked” meals in grocery stores, have pizzas delivered, and eat fast food in our cars. But the popularity of home cooking is increasing. Julia Child helped start the trend in the 1960s with her cooking show, “The French Chef.” Now there are many food-related magazines, television shows, and specialty stores to tempt our taste buds. Americans are rediscovering good food.

Coming Together

Think food is used only to nourish our bodies? Think again! We use food to celebrate, to stereotype people, to express love or compassion, to treat ourselves, to compete or make money, to remember our roots, to garner compliments, and to come together as a community. Our tastes in food have changed over time depending on where we live, what we can afford, and what’s in fashion.

Church members often gathered for “dinners on the ground.” Blankets were laid on the grass and then piled with a bounty of delicious foods. Lucile Dees McVay attended such dinners during the late 1920s and 1930s at the annual Decoration Day at Wedington Cemetery. Every woman brought her specialty, whether it was homemade bread, deviled eggs, or candied sweet potatoes. Young Lucile waited patiently by her mother’s salmon cakes until the blessing was said–then she helped herself! Canned salmon was so expensive that these treats were rarely made at home.

There’s something about food that has made us come together over the years. Neighbors gathered for community events such as house raisings, funerals, and school functions. During John Quincy Wolf’s youth in the 1870s Ozarks, women came together to prepare food for the men building a house. When the dinner horn was sounded promptly at noon everyone came running to partake of the fried ham, preserves, pumpkin pie, hog jowls, biscuits and cornbread, cabbage, sausage, turnips, coffee, and greens.

Families gathered for celebrations such as holidays, birthdays, and weddings. When Wayman Hogue was growing up in the late 1800s, a wedding was held at his home in the Ozarks. A dozen chickens were fattened with corn and lots of cakes, custards, pies, and light [white] bread were made. Tables placed end-to-end in the yard held three boiled hams. The hams’ skin had been removed and large round dots of black pepper added as decoration. Coffee was expensive so sassafras tea was served.

Picnics were fun occasions for friends and family. Betty Greathouse of the Greathouse Springs community southwest of Springdale liked having big picnics in her yard. Sawhorses were placed under the old sycamore tree and outfitted with wide boards and overlapping tablecloths. Family members fried chicken and guests brought covered dishes of food. One of the community elders said the blessing, “usually profound and well spoken.”

Tidbits

Members of the Springdale Woman’s Civic Club, February 1953. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection/McRoberts, photographer (S-77-9-22)

Every region of the country has dishes that it’s known for. When Charles Morrow Wilson grew up in Fayetteville in the early 1900s, typical Ozark fare included Johnny cakes, home-cured pork, Injun spareribs (a stew made with salt pork, sweet potatoes, green peppers, and corn), sweet potato puddings, hog jowls with cowpeas, and turnip greens with “pot likker,” the juice left behind after the greens and salt porkwere cooked in water.

During Wayman Hogue’s childhood in the Ozarks, “old man Adams” was the local barbeque expert. Families contributed sheep, goats, hogs, and calves to the annual Fourth of July celebration. Ditches were dug about 20 feet long and filled with oak and hickory. The evening before the big day Adams and his crew hung the carcasses from long poles and began cooking the meat.

Cooking techniques and recipes were often passed from mother to daughter. In the 1910s county extension offices formed to bring “practical demonstrations” in agriculture and home economics to rural communities. Home Demonstration clubs hosted university specialists who taught scientific canning techniques, nutrition, and other homemaking skills. Canned goods not only provided food for the family, it was a good way to earn extra income.

Food was used for charitable purposes such as raising money for schools and community buildings. At box suppers and pie suppers men vied with one another to bid on the food prepared by the prettiest girl or the best cook. Bringing gifts of food to a new or struggling family was common. In Alpena a “pounding” was held for the preacher and his family. Church members brought eggs, fruit, coffee, canned goods, garden produce, sugar—whatever they wished—often in one-pound amounts.

Food can identify people in many ways. In Tontitown, the community’s early Italian roots are proudly expressed in the spaghetti served at the annual Grape Festival. But food is offensively used by some to stereotype people, such as linking traditional Ozarkers to possum or African Americans to watermelon.

Photo Gallery

Lunch ladies, Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Youth Camp near Springdale, June 1970. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-2000-2-75)

Dinner on the ground, Joseph H. Moore residence, Cane Hill, circa 1910. Martha Moore Collection (S-85-277-46)

Community supper, Springdale, 1950s. Calvin Mulkey, photographer. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-77-9-35)

Bonnie Harold competing in a pie-eating contest, Springdale High School, May 1974. Morris White, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 5-1974 #14)

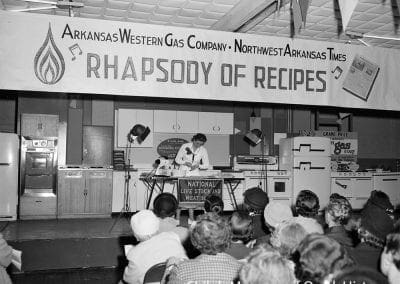

Cooking school, Fayetteville, February 1957. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 5 56.8-46)

Gov. Orval Faubus (center) and Alta Faubus, Northwest Arkansas Livestock and Poultry Show barbeque, Springdale, 1955. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-77-9-37)

Preparing cheese bread, Rogers Riding Club, Northwest Arkansas Cavalcade trail ride, 1950s. From left: Gene Thrasher, Hubert Lock, unidentified, Newt Hailey, Elmer Hatfield. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-92-64-7)

Arlene Kelly Stewart, Jug Wheeler’s Drive-In, Dickson Street, Fayetteville, 1959. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 4 4×5.74)

Pancake breakfast, Central Fire Station, Fayetteville, October 1973. Ken Good, photographer. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 28 73.17)

Poor Boy Market, Springdale, June 1972. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-4397)

Chili Cookoff contestants, Springdale, October 1984. Barry Thomas, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 10-27-1984)

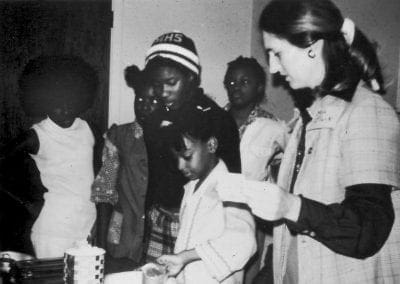

Cub Scouts preparing baskets for the needy, Jones Elementary School, Springdale, December 1973. From left: Davon Bookout, Stanley Murray, Randy Appleby, Dewayne Stamps. Morris White, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 12-1973-7)

Eating popcorn, Washington County Fair, September 1957. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-456)

Dishing up spaghetti, 68th annual Grape Festival, Tontitown, August 1966. From left: Rosie Finn, Esther Marendo Pianalto, Mary “Pete” Tessaro. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 8-11-1966)

Rolling tamales, La Familia Restaurant, Fayetteville, November 1995. Rusty Garrett, photographer. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT 11-15-1995)

Cooking demonstration, Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, Fayetteville, 1970s. Mary Gilbert Collection (S-85-173-7)

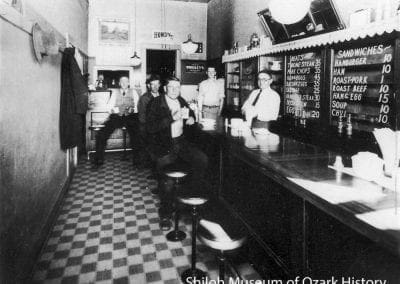

King Chicken restaurant, Fayetteville, January 1959. Ray Watson, photographer. Ray Watson Collection (S-2002-50-806)

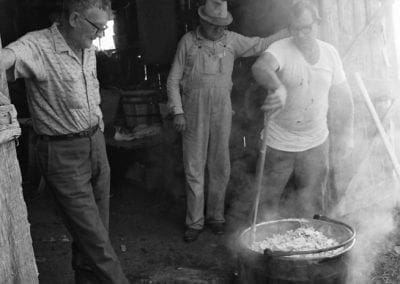

Making apple butter, Henry Tabor farm, Springdale, September 1972. From left: Henry Tabor, Ray Tabor, Ed Tabor. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 9-27-1972)

Making apple butter, Henry Tabor farm, Springdale, September 1972. From left: Faye Tabor, Elizabeth Martin. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 9-27-1972)

Thanksgiving celebration, Fayetteville, November 1962. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 106 D 62-1)

Springdale Bakery, Springdale, about 1927. From left: Jim Pennington, Harvey Baker, Nell Baker. LaJoice Atkins Collection (S-93-84-109)

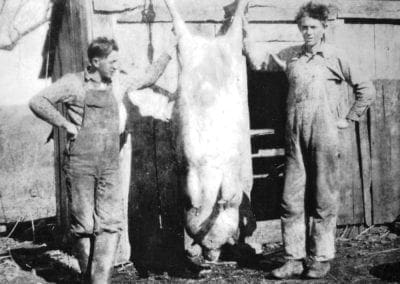

Butchered hog, Slow Tom Mountain, Madison County, 1936. From left: Ernest Anderson, James S. “Jim” Burnett. Joy Russell Collection (S-96-38-22)

Kendrick and/or Cardwell family picnic, Springdale area, 1910s. Tommy and Darlette Kendrick Collection (S-2006-24-19)

Table set in honor of Mary “Mate” Kelly Phillip’s 50th birthday, near Hindsville, April 1909. From left: Mate Phillips, Cynthia E. Kelly Bedingfield. Willie Bohannan Collection (S-83-82-6)

Credits

Arnold, Eleanor, editor. Voices of American Homemakers: An Oral History Project of the National Extension Homemakers Council. Metropolitan Printing Service, Inc., 1985.

Hill, Ethel D. “Women’s Cash from Canning.” Arkansas Countryman [Fayetteville, AR], April 12, 1928.

Jones, W. G. “Sugar Cookies.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 5, No. 5 (July 1960).

Hogue, Wayman. Back Yonder. New Rochelle, NY: Knickerbocker Press, 1932.

McNeil, W. K. and William M. Clements, editors. An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

McVay, Lucile Dees. “Dinner on the Ground.” March 1999. Shiloh Museum research files.

White, T. A. Jr. “Memories of Greathouse Springs.” Ozarks Mountaineer, March-April 1985.

Wilson, Charles Morrow. The Bodacious Ozarks: True Tales of the Backhills. New York: Hastings House Publishers, 1959.

Wolf, John Quincy. Life in the Leatherwoods: An Ozark Boyhood Remembered. Little Rock: August House, 1988.