Healing Waters

Online ExhibitWhere Do Springs Come From?

In Northwest Arkansas, the geologic layer known as the Springfield Plateau contains large areas of porous soil and rock. Rain passes through easily, down to a level called the “zone of saturation.” The zone is a place where water completely fills every opening in and around rock and soil, much like water fills the empty spaces in a bowl full of marbles. The upper surface of this zone is the water table. Below are aquifers, bodies of saturated rock through which water passes easily.

Springs can form on hillsides where a water table, an aquifer, or a water-filled underground passageway intersects with the slope of the land. Gravity causes the water to flow out and down the hillside. Springs can also form when pressure from the earth forces groundwater up to the surface, like when water is pushed out of a soft plastic bottle as it is squeezed.

Many springs produce fresh water, perfect for drinking. Some springs have a high mineral content, a result of the water dissolving the rock it passes through. For instance, limestone dissolves into calcium carbonate while dolomite dissolves into calcium magnesium carbonate. Minerals can color and flavor the water or, like sulphur, make it smell bad. Some minerals create carbon dioxide bubbles, making the water fizzy.

The Rise of Health Resorts and Mineral Springs

The belief in the healing properties of mineral water has been around since ancient times. Although there were spas in colonial America, they gained in popularity before and after the Civil War, when nationwide prosperity filled many with the desire to travel. A growing interest in the healing arts and faith cures, coupled with increasingly affordable railway fares, caused people, especially the well-to-do, to flock to natural, healthful settings like mountains and mineral springs.

As with patent-medicine advertising, mineral-water promoters made fantastic, sweeping claims. Springs were said to alleviate a host of illnesses including rheumatism, catarrh (inflammation of mucus membranes), tuberculosis, hay fever, diabetes, dyspepsia (indigestion), asthma, jaundice, malaria, paralysis, neuralgia (intense nerve pain), gout, cancer, dropsy (excess fluid in tissues or body cavities), and “female troubles.”

Health resorts latched onto new scientific and technological advancements as a way to promote their offerings. As the wonder of electricity became available commercially during the late 19th century, electrotherapy and electromagnetism treatments came into vogue. Some springs were deemed “electric” for their supposed ability to magnetize metal. When chemist Marie Curie discovered the element of radium in 1898 and coined the word “radioactivity,” radioactive water became fashionable and was purportedly found in spring after spring.

While many physicians and the public shared a belief in the healing powers of mineral waters, there were naysayers. Some felt that cures were often the result of the rest and recreation received during treatment. The earliest, most popular health resort in America was at Saratoga Springs, New York, beginning in the early 1800s. In Arkansas, the first bathhouse at Hot Springs was built in 1830. It wasn’t until the 1880s that health resorts began operating in the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks.

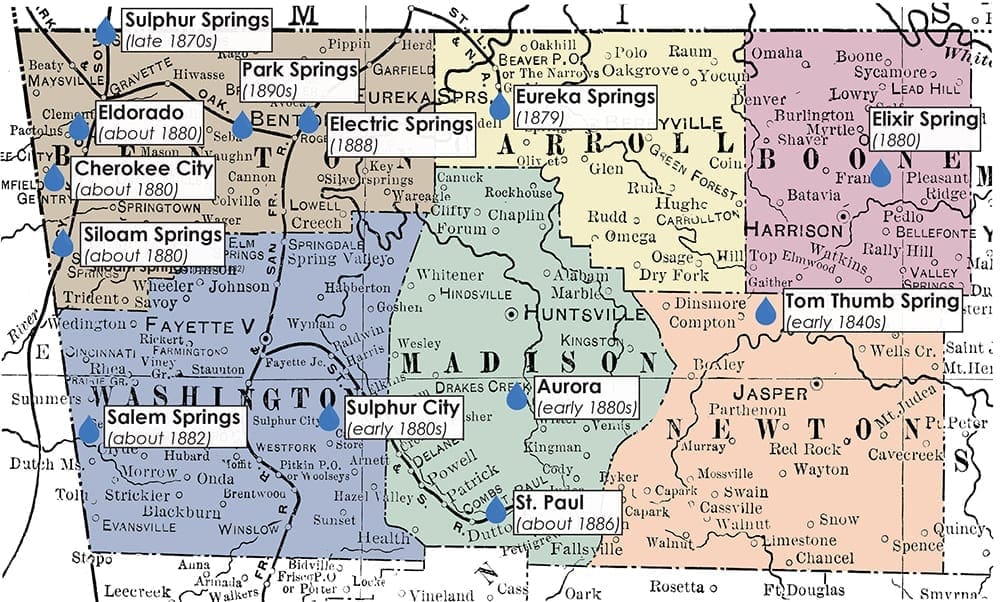

Healing Waters in the Arkansas Ozarks

In 1879 tales of miracle cures at what would become Eureka Springs spread like wildfire. Eureka’s immediate fame and fast-paced prosperity caught the eye of several area communities blessed with mineral springs. Health resorts began springing up in the early 1880s, touting their healing waters in hopes of attracting travelers—and their pocketbooks. Medicinal springs were big business. Over in western Benton County, speculators in Cherokee City moved to nearby Eldorado after Cherokee City’s prospects went bust after 1882. And when much of Eldorado washed away during a flood a year or two later, many of the same entrepreneurs moved to the newly booming town of Siloam Springs.

The success of these communities depended on transportation. For instance, when Siloam Springs began touting its waters and building hotels in the early 1880s, it was banking on the likelihood of a railroad coming through. The town’s population quickly swelled, only to drop when no railroad came. After the Kansas City, Pittsburgh & Gulf Railroad finally steamed into town in 1893, the population rose once more.

To help convince the public of a spring’s health benefits, a water sample was analyzed and the results advertised, with the claim that certain springs would cure specific ailments. Town boosters promoted the springs through newspaper stories, advertisements, and souvenir photographs. Testimonials from satisfied patients were sent to newspapers throughout the country in an effort to lure health seekers.

There was some rivalry between spring communities. For example, an 1880 letter in the Fayetteville Democrat noted that the countryside around Siloam Springs was more attractive than other area springs. There was also backlash over all the hype. In an 1882 edition of The [Harrison] Times, one wit quipped, “The water in the Court House well is either developing remarkable medicinal qualities, or else there is a dead cat in it.”

The End of an Era

Unfortunately, the rise of Northwest Arkansas health resorts coincided with the end of the nation’s interest in “taking the waters.” Many factors contributed to bring this about. By the 1890s the scientific method of systematic observation and experimentation was being applied to all sorts of scientific and social issues, leading people to question the folk wisdom of “healing waters.” The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was designed to protect consumers from dangerous ingredients and false advertising. It included regulations regarding how mineral water could be promoted.

The 1910s saw major advances in the science and standards of medical care, leading to the professionalism of medicine. Reliance on natural cures faded by the end of World War I, when the cause and treatment of diseases were better understood and new medicines were being developed. With the increasing affordability of the automobile came a desire to travel to new places, without having to rely on the railroads’ set destinations or timetables. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, financial difficulties faced by would-be travelers helped end the era of healing waters.

Still, the allure of the waters continued. In the 1940s, visitors to patients at John Brown University Hospital in Siloam Springs would sometimes bring a jug of spring water, believing it better for the patient than city tap water. In 1957 Sulphur Springs leadership was considering a $100,000 project to build a modern hotel and bathhouse to fill the needs of health seekers and tourists. Nothing came of it. In later years the town received requests to send bottles of lithia mineral water far and wide, to folks hoping to cure their ailments.

Springs Today

Today, water quality throughout the Ozarks is threatened. Water sources are being contaminated with pollutants from farms, industries, and residences. The Giardia parasite, which causes intestinal problems, is also a problem. Signs warning against drinking the water are posted at several public springs.

Area mineral springs are also threatened by fading memories of their whereabouts or lack of resources to protect and restore them to their glory. However, in the tourist town of Eureka Springs, many springs are well-maintained and easily accessible to visitors.

Where Do Springs Come From?

In Northwest Arkansas, the geologic layer known as the Springfield Plateau contains large areas of porous soil and rock. Rain passes through easily, down to a level called the “zone of saturation.” The zone is a place where water completely fills every opening in and around rock and soil, much like water fills the empty spaces in a bowl full of marbles. The upper surface of this zone is the water table. Below are aquifers, bodies of saturated rock through which water passes easily.

Springs can form on hillsides where a water table, an aquifer, or a water-filled underground passageway intersects with the slope of the land. Gravity causes the water to flow out and down the hillside. Springs can also form when pressure from the earth forces groundwater up to the surface, like when water is pushed out of a soft plastic bottle as it is squeezed.

Many springs produce fresh water, perfect for drinking. Some springs have a high mineral content, a result of the water dissolving the rock it passes through. For instance, limestone dissolves into calcium carbonate while dolomite dissolves into calcium magnesium carbonate. Minerals can color and flavor the water or, like sulphur, make it smell bad. Some minerals create carbon dioxide bubbles, making the water fizzy.

The Rise of Health Resorts and Mineral Springs

The belief in the healing properties of mineral water has been around since ancient times. Although there were spas in colonial America, they gained in popularity before and after the Civil War, when nationwide prosperity filled many with the desire to travel. A growing interest in the healing arts and faith cures, coupled with increasingly affordable railway fares, caused people, especially the well-to-do, to flock to natural, healthful settings like mountains and mineral springs.

As with patent-medicine advertising, mineral-water promoters made fantastic, sweeping claims. Springs were said to alleviate a host of illnesses including rheumatism, catarrh (inflammation of mucus membranes), tuberculosis, hay fever, diabetes, dyspepsia (indigestion), asthma, jaundice, malaria, paralysis, neuralgia (intense nerve pain), gout, cancer, dropsy (excess fluid in tissues or body cavities), and “female troubles.”

Health resorts latched onto new scientific and technological advancements as a way to promote their offerings. As the wonder of electricity became available commercially during the late 19th century, electrotherapy and electromagnetism treatments came into vogue. Some springs were deemed “electric” for their supposed ability to magnetize metal. When chemist Marie Curie discovered the element of radium in 1898 and coined the word “radioactivity,” radioactive water became fashionable and was purportedly found in spring after spring.

While many physicians and the public shared a belief in the healing powers of mineral waters, there were naysayers. Some felt that cures were often the result of the rest and recreation received during treatment. The earliest, most popular health resort in America was at Saratoga Springs, New York, beginning in the early 1800s. In Arkansas, the first bathhouse at Hot Springs was built in 1830. It wasn’t until the 1880s that health resorts began operating in the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks.

Healing Waters in the Arkansas Ozarks

In 1879 tales of miracle cures at what would become Eureka Springs spread like wildfire. Eureka’s immediate fame and fast-paced prosperity caught the eye of several area communities blessed with mineral springs. Health resorts began springing up in the early 1880s, touting their healing waters in hopes of attracting travelers—and their pocketbooks. Medicinal springs were big business. Over in western Benton County, speculators in Cherokee City moved to nearby Eldorado after Cherokee City’s prospects went bust after 1882. And when much of Eldorado washed away during a flood a year or two later, many of the same entrepreneurs moved to the newly booming town of Siloam Springs.

The success of these communities depended on transportation. For instance, when Siloam Springs began touting its waters and building hotels in the early 1880s, it was banking on the likelihood of a railroad coming through. The town’s population quickly swelled, only to drop when no railroad came. After the Kansas City, Pittsburgh & Gulf Railroad finally steamed into town in 1893, the population rose once more.

To help convince the public of a spring’s health benefits, a water sample was analyzed and the results advertised, with the claim that certain springs would cure specific ailments. Town boosters promoted the springs through newspaper stories, advertisements, and souvenir photographs. Testimonials from satisfied patients were sent to newspapers throughout the country in an effort to lure health seekers.

There was some rivalry between spring communities. For example, an 1880 letter in the Fayetteville Democrat noted that the countryside around Siloam Springs was more attractive than other area springs. There was also backlash over all the hype. In an 1882 edition of The [Harrison] Times, one wit quipped, “The water in the Court House well is either developing remarkable medicinal qualities, or else there is a dead cat in it.”

The End of an Era

Unfortunately, the rise of Northwest Arkansas health resorts coincided with the end of the nation’s interest in “taking the waters.” Many factors contributed to bring this about. By the 1890s the scientific method of systematic observation and experimentation was being applied to all sorts of scientific and social issues, leading people to question the folk wisdom of “healing waters.” The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was designed to protect consumers from dangerous ingredients and false advertising. It included regulations regarding how mineral water could be promoted.

The 1910s saw major advances in the science and standards of medical care, leading to the professionalism of medicine. Reliance on natural cures faded by the end of World War I, when the cause and treatment of diseases were better understood and new medicines were being developed. With the increasing affordability of the automobile came a desire to travel to new places, without having to rely on the railroads’ set destinations or timetables. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, financial difficulties faced by would-be travelers helped end the era of healing waters.

Still, the allure of the waters continued. In the 1940s, visitors to patients at John Brown University Hospital in Siloam Springs would sometimes bring a jug of spring water, believing it better for the patient than city tap water. In 1957 Sulphur Springs leadership was considering a $100,000 project to build a modern hotel and bathhouse to fill the needs of health seekers and tourists. Nothing came of it. In later years the town received requests to send bottles of lithia mineral water far and wide, to folks hoping to cure their ailments.

Springs Today

Today, water quality throughout the Ozarks is threatened. Water sources are being contaminated with pollutants from farms, industries, and residences. The Giardia parasite, which causes intestinal problems, is also a problem. Signs warning against drinking the water are posted at several public springs.

Area mineral springs are also threatened by fading memories of their whereabouts or lack of resources to protect and restore them to their glory. However, in the tourist town of Eureka Springs, many springs are well-maintained and easily accessible to visitors.

Major Springs and Health Resorts

Eureka Springs — Carroll County

“Our facilities enable us to give expert electrical treatment . . . and massage, in all their forms. . . . We also give the radiant bath, which has proven so efficient an improvement upon the Turkish and Russian baths; also, in connection with our treatment, all forms of tub baths—needle, sitz, leg, etc., with or without massage, as indicated.”

Eureka Sanitarium Company

1897

According to sworn testimony, in 1856 Dr. Alva Jackson was out in the woods, recovering a wounded hunting dog, when he came upon a trickle of water. Jackson’s son, who had sore eyes, was told to bathe them with spring water and was cured. Thinking he had found a fabled spring which “performed great cures,” Jackson dug out gravel and mud and discovered a smooth stone basin. Soon he began treating patients with this miracle liquid.

In May 1879 Judge Levi Saunders of Berryville used the Basin Spring’s water in hopes of curing his erysipelas, a bacterial disease which causes fever and inflamed patches on the skin. Within five weeks his health was improved. News of his amazing cure spread quickly. By the Fourth of July, twenty or so families had come seeking treatment. Sensing a town in the making, Saunder’s son suggested the name “Eureka,” from the ancient Greek word meaning “I have found it!” Soon hotels, bathhouses, businesses, and homes were rising from the hillsides. By the 1880 census, the resident population was listed as 3,000. More springs were found and named, including Arsenic, Dairy, East Mountain, Catalpa, Magnetic, Harding, Oil, Crescent, Sweet, and Iron. Some provided fresh water; others were believed to have healing properties.

In L. J. Kalklosch’s lengthy 1881 history of the town, he included “A Few Hints to Visitors.” He recommended they purchase walking sticks and cups to carry in their pockets, to watch for confidence men, to drink from each spring, and to visit all places of interest, while remembering, “there are places you should not visit” (saloons). Most importantly, visitors were not to condemn the springs if they weren’t cured.

The first health seekers came by horse or carriage, but town leaders knew a railroad would ensure growth and prosperity. In 1883 the Eureka Springs Railway came to town, connecting with the Frisco Railway at Seligman, Missouri, 18.5 miles away. The track was expensive, costing around $25,000 per mile. One-way fares were grossly inflated at $1.75.

The town flourished. The springs were enhanced with elaborate masonry enclosures. Expensive, multistory hotels catered to the wealthy while others found lodging in boarding houses. Bathhouses offered massages and various kinds of water and steam baths. Private doctors and sanitariums treated the infirm. The Magnetic College and Sanitarium opened in 1900 near Magnetic Spring, where the water was said to cure addiction to patent medicines, which contained alcohol and narcotics like cocaine, heroin, and morphine.

By 1904 the town’s water was bottled under the Ozarka label. Each month 25 to 30 railcars of water and flavored beverages were shipped out. In 1956 the Eureka Springs Water Company, which owned the Ozarka brand, shipped over 300 million gallons of water, with only half coming from Eureka; the rest came from Hot Springs. The company changed hands in 1967 and operations were moved out of state. Now Ozarka water comes from Texas.

Protection of the town’s water and its reputation was important. An ordinance passed around 1880 warned that “all persons washing their person or clothes in or above the basins of all public springs shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.” In 1920 several people were diagnosed with typhoid fever. Tests proved the water to be unsafe. Seeing the need to reassure the public, a tax was levied to improve and protect the town’s water. Several electronic water-treatment towers were installed at area springs at a total cost of $17,000.

Eureka’s importance as a spa town faded in the 1910s. Many of the grand buildings were repurposed or fell vacant for a time. Over the next few decades artists and writers began trickling in; many more came in the 1970s and 1980s. Eurekans came to realize that they had something special. In 1970 the Eureka Springs Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Eleven years later a city commission was established to maintain city-owned parks and springs. Tourism is the town’s main business today. Art galleries, music festivals, spa retreats, outdoor recreation, Victorian architecture, religious and historical attractions, wedding venues, and beautiful springs draw a diverse crowd.

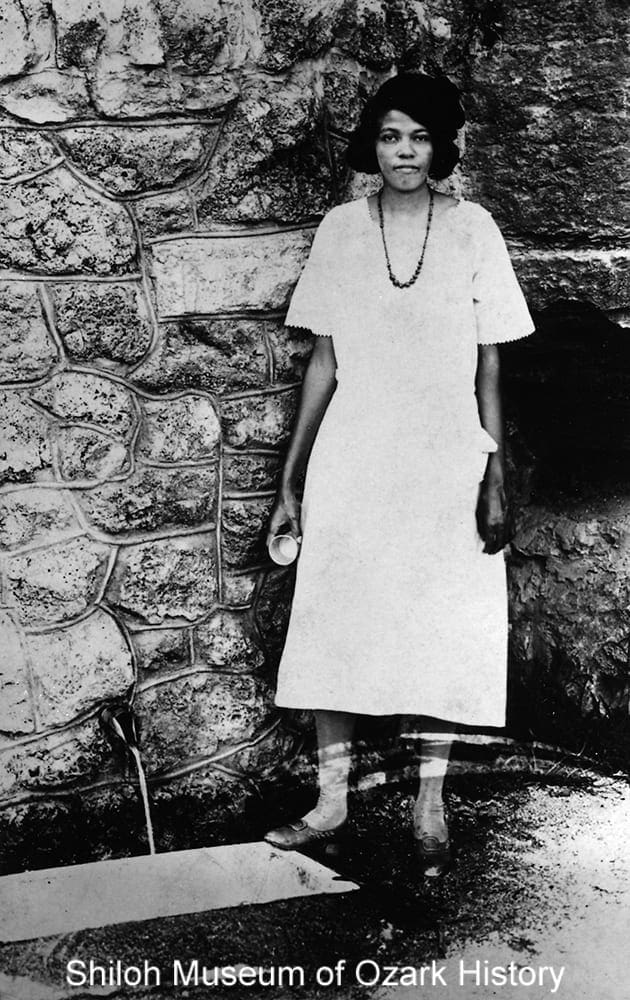

“When people came here in the summer time, quite often they would bring their servants. They all would meet at Harding Spring—the Negro Spring—drink the water, and have songfests. It was beautiful music. . . . Most people in town were afraid of the blacks. That’s just how it was in the South.”

Virginia Tyler

January 6, 1997

Arkansas Historical Quarterly

Summer 1997

77-66-24

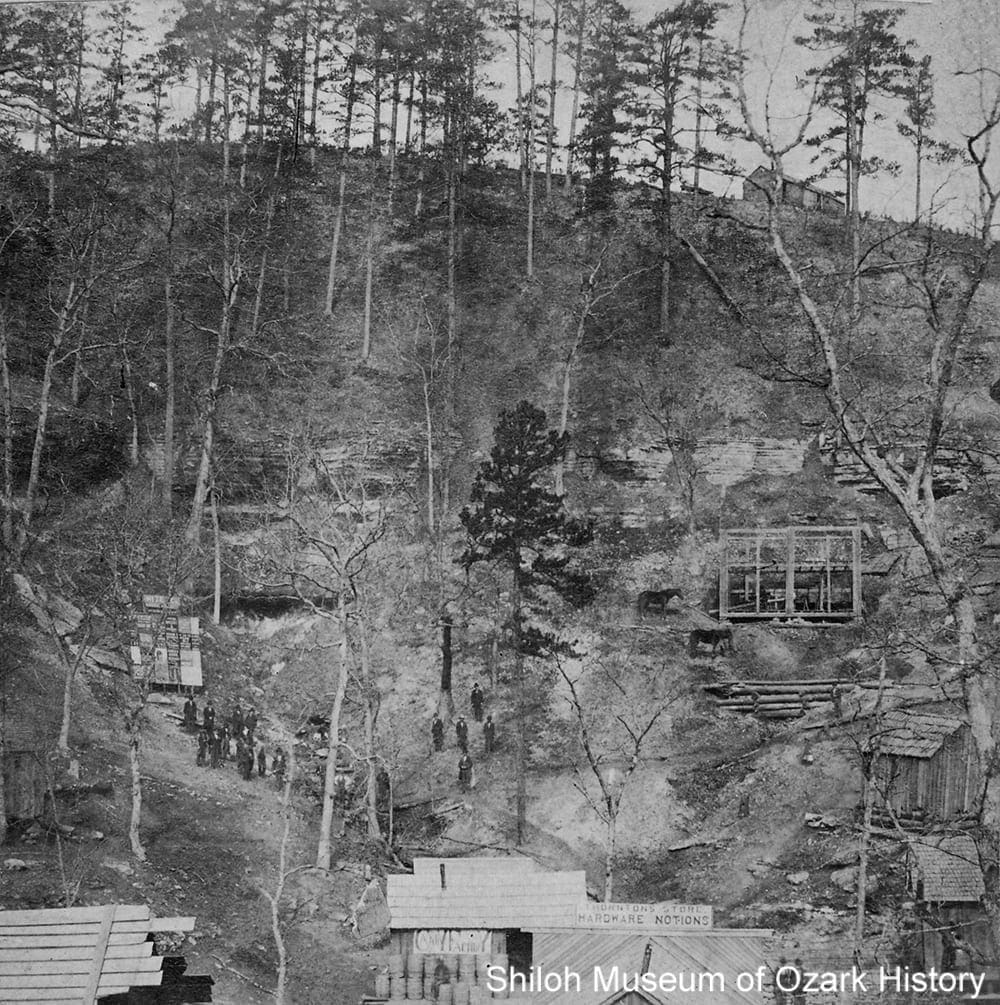

Basin Spring with billboard, candy factory, Thornton’s store, and a building under construction, circa 1880. A town quickly formed around Basin and the other springs. Sensing a business opportunity, O. D. Thornton became the town’s first merchant in July 1879, offering groceries, hardware, and notions like calico cloth, which he cut with a pocketknife. Lockwood W. Searcy Collection (S-77-66-24)

83-325-38

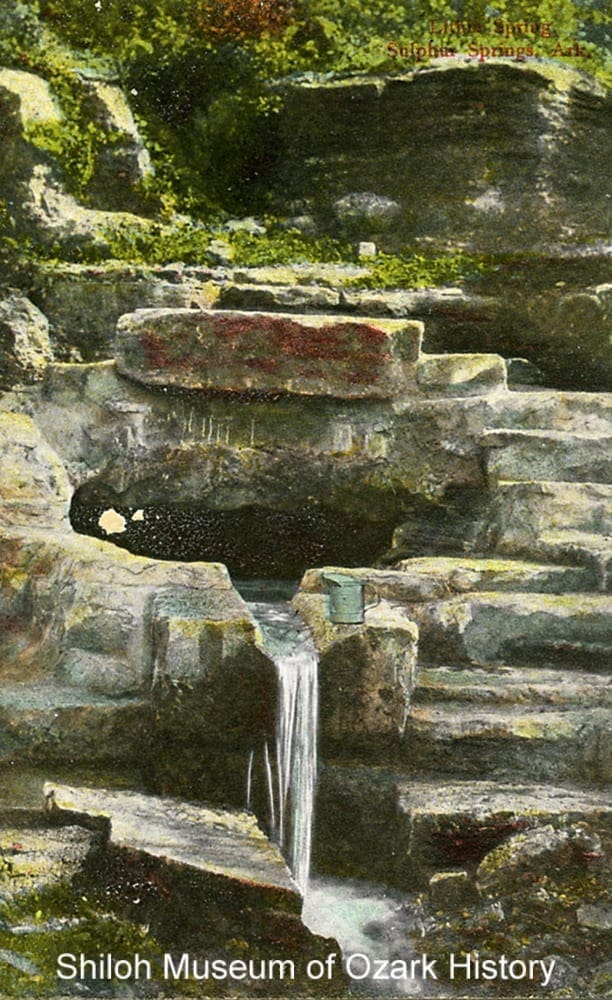

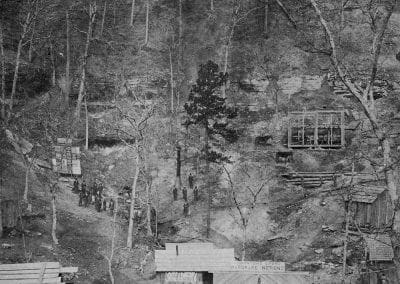

Arsenic Spring with wood water trough, early 1880s. Early health seekers would have found the springs in their most natural state—small flows of water coming through the hillside. Visitors navigated the steep, rugged terrain as best they could. In the 1880s and 1890s elaborate rockwork or wood structures were added to many springs to improve access and beautify the town. F. F. Fyler, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-38)

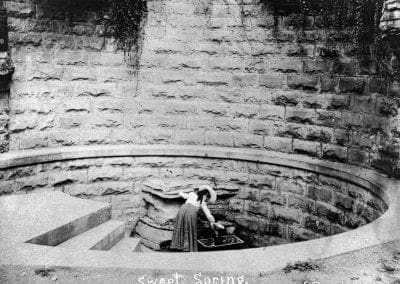

83-325-106

Sweet Spring (formerly Spout Spring), 1895. Spout spring was once used for baptisms. The Waldrip brothers built the masonry wall around the spring in 1885. The water was used for drinking as well as for a laundry and bathhouse. Gray’s Studio, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-106)

83-325-40

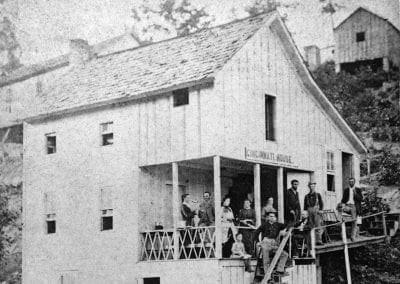

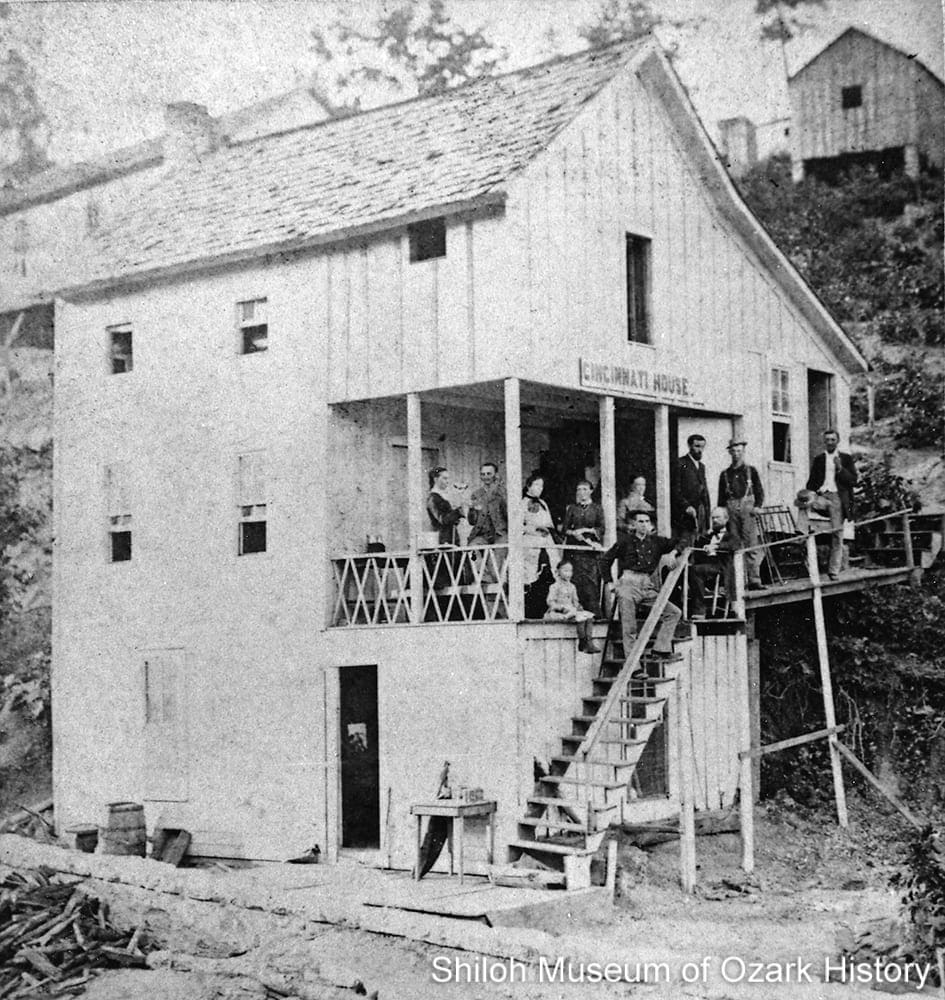

Cincinnati House, early 1880s. Visitors stayed in hotels, boarding houses, or in private homes, depending on their desired level of service and price. Like many of Eureka’s buildings, the Cincinnati, a small boarding house managed by J. T. Alexander, was built into the steep hillside. It was in operation in 1881 but by 1884 it was either renamed or no longer in business. F. F. Fyler, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-40)

83-325-105

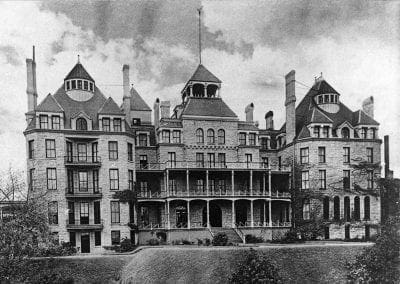

Crescent Hotel, late 1880s. Built by the Frisco Railroad and wealthy investors of the Eureka Springs Improvement Company, the $294,000 luxury hotel opened in 1886. After the decline of tourism in the early 1900s, the building was home to a girl’s school and later a bogus cancer clinic. Today the newly restored Crescent markets itself as “America’s Most Haunted Hotel.” Gray’s Studio, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-105)

83-325-133

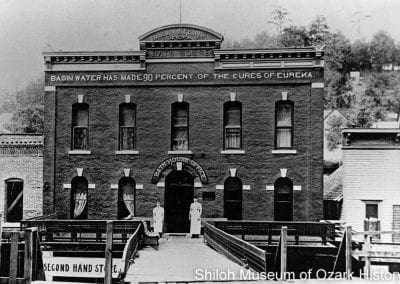

Sign for Eureka Springs Water Condensing Company, Basin Spring, early 1880s. Owned by John Tibbs, an 1881 ad for the company noted that it shipped water in paraffin-lined barrels and kegs and glass bottles. It also sold “Concentrated Eureka Springs Eye Water,” 35 cents per vial, and concentrated Eureka Soap, which possessed “excellent medicinal qualities.” George R. Calohan, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-133)

86-122-44

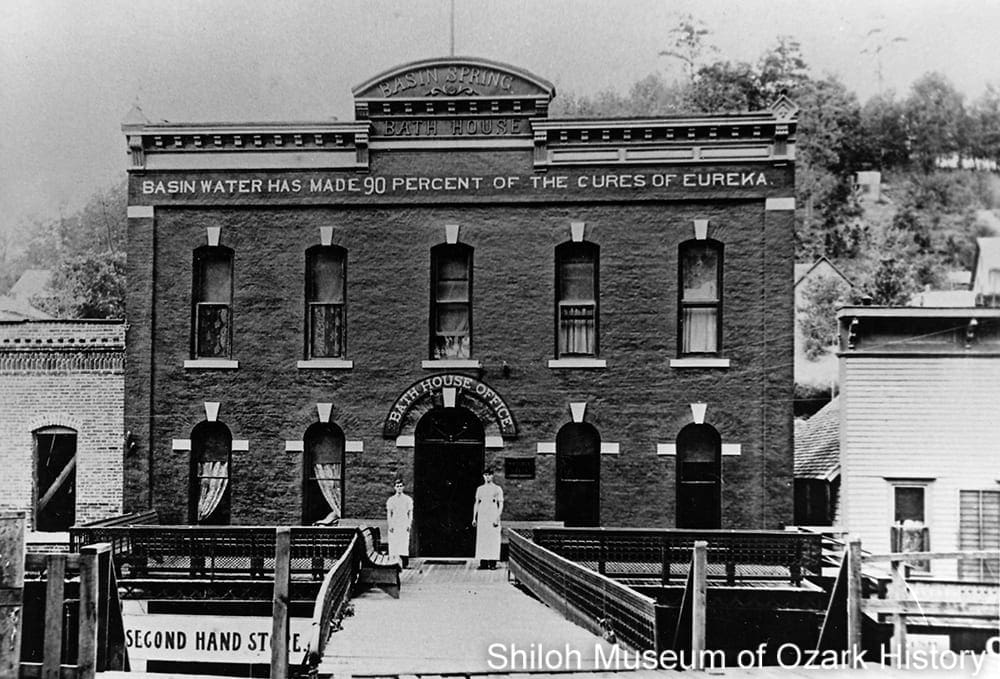

Basin Spring Bath House with attendants, 1903. The Eureka Springs Water Company of St. Louis began shipping Basin Spring water in 1880, running pipes down the hillside. The company filled their barrels at night to allow for daytime use by the spring’s health seekers. It also ran the Basin Spring Bathhouse. Eugene Smith, photographer. (S-86-122-44)

86-122-43

Bathing room, Palace Hotel and Bath House, 1910s–1920s. Built for George T. Williams in 1901, the Palace Bath House offered water baths and showers, Turkish steam baths, and massages. It had a cafe, laundry, and barbershop and, for a time, operated as a brothel. Customers at today’s spa can enjoy a steam or a massage. Eugene Smith, photographer. (S-86-122-43)

99-66-372

Mrs. O. W. Coleman at Harding Spring, 1920s. There was a small African-American presence in Eureka in its early years, including residents who worked as barbers, brick masons, and Crescent Hotel maids. While some African Americans came for health reasons, others came as the servants of white health seekers. Racial segregation led to separate churches, hotels, schools, neighborhoods, and even springs. For a time, Harding was the only spring African Americans were allowed to visit. The rock wall to Mrs. Coleman’s right was part of an electronic ultraviolet water treatment system. It was added in 1921, after water from the town’s springs was deemed unsafe for drinking. Eureka Springs Historical Museum Collection (S-99-66-372)

Eureka Springs Photo Gallery

Basin Spring with billboard, candy factory, Thornton’s store, and a building under construction, circa 1880. A town quickly formed around Basin and the other springs. Sensing a business opportunity, O. D. Thornton became the town’s first merchant in July 1879, offering groceries, hardware, and notions like calico cloth, which he cut with a pocketknife. Lockwood W. Searcy Collection (S-77-66-24)

Arsenic Spring with wood water trough, early 1880s. Early health seekers would have found the springs in their most natural state—small flows of water coming through the hillside. Visitors navigated the steep, rugged terrain as best they could. In the 1880s and 1890s elaborate rockwork or wood structures were added to many springs to improve access and beautify the town. F. F. Fyler, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-38)

Sweet Spring (formerly Spout Spring), 1895. Spout spring was once used for baptisms. The Waldrip brothers built the masonry wall around the spring in 1885. The water was used for drinking as well as for a laundry and bathhouse. Gray’s Studio, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-106)

Cincinnati House, early 1880s. Visitors stayed in hotels, boarding houses, or in private homes, depending on their desired level of service and price. Like many of Eureka’s buildings, the Cincinnati, a small boarding house managed by J. T. Alexander, was built into the steep hillside. It was in operation in 1881 but by 1884 it was either renamed or no longer in business. F. F. Fyler, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-40)

Crescent Hotel, late 1880s. Built by the Frisco Railroad and wealthy investors of the Eureka Springs Improvement Company, the $294,000 luxury hotel opened in 1886. After the decline of tourism in the early 1900s, the building was home to a girl’s school and later a bogus cancer clinic. Today the newly restored Crescent markets itself as “America’s Most Haunted Hotel.” Gray’s Studio, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-105)

Basin Spring Bath House with attendants, 1903. The Eureka Springs Water Company of St. Louis began shipping Basin Spring water in 1880, running pipes down the hillside. The company filled their barrels at night to allow for daytime use by the spring’s health seekers. It also ran the Basin Spring Bathhouse. Eugene Smith, photographer. (S-86-122-44)

Bathing room, Palace Hotel and Bath House, 1910s–1920s. Built for George T. Williams in 1901, the Palace Bath House offered water baths and showers, Turkish steam baths, and massages. It had a cafe, laundry, and barbershop and, for a time, operated as a brothel. Customers at today’s spa can enjoy a steam or a massage. Eugene Smith, photographer. (S-86-122-43)

Mrs. O. W. Coleman at Harding Spring, 1920s. There was a small African-American presence in Eureka in its early years, including residents who worked as barbers, brick masons, and Crescent Hotel maids. While some African Americans came for health reasons, others came as the servants of white health seekers. Racial segregation led to separate churches, hotels, schools, neighborhoods, and even springs. For a time, Harding was the only spring African Americans were allowed to visit. The rock wall to Mrs. Coleman’s right was part of an electronic ultraviolet water treatment system. It was added in 1921, after water from the town’s springs was deemed unsafe for drinking. Eureka Springs Historical Museum Collection (S-99-66-372)

Siloam Springs — Benton County

“The most renowned spring gushes from a limestone bluff…and of the curative powers of its waters we do not want any better evidence than we have, while within a few feet we have one of the finest Chalybeate [iron] springs in the state, and further up the valley . . . we have an oil spring . . . Now we do not expect to rival (in numbers) Eureka . . . But we think we are able to exhibit some as remarkable cures as any of them, and besides we have a much more attractive surrounding county than any of the springs named.”

Fayetteville Democrat

May 29, 1880

Eureka Springs’ instant success as a health resort must have factored into John Valentine Hargroves’ plan in 1880 to capitalize on the many springs found in the little community of Hico, on the western border of Arkansas. Soon a town site was laid out, plots of land were sold, and eager folks moved into the area. About that time Dr. H. Perry recommended to a patient that he drink the water of a certain spring to ease the pain he felt while eating and drinking. Perry named the water source “Siloam Spring” after a Bible verse instructing a man to “wash in the pool of Siloam” to heal his eyes.

The town of Siloam Springs was incorporated in 1881, with every expectation that a railroad would soon be built to it. But the railroad didn’t come. In 1881 the population was over 2,200; by 1890 it had dropped to 821. Business leaders labored hard to get the needed railroad. Working with the Kansas City, Pittsburgh & Gulf Railroad, they donated land for the depot and track right-of-way and promised $20,000. December 1893 saw the first rail passengers into town. Like its neighbor Sulphur Springs, Siloam offered many amenities for visitors including several city parks, paths for strolling, band concerts, hotels and restaurants, and an active Chautauqua hall.

Over twenty springs were said to be located within town. An 1898 newspaper article proclaimed the health benefits of the town’s waters and climate as helping those who suffered from a variety of ailments, including jaundice, chronic skin diseases, rheumatism, constipation, paralysis, hay fever, asthma, and malaria. Springs such as Twin, Siloam, Seven, and Spout offered fresh, pure water, said to be good for flushing the disease-causing impurities from a person’s body. Iron Spring was the only mineral spring, although one of the Twin springs was said to contain trace amounts of arsenic. When Helen “Johnnie” Johnson worked as a nurse at John Brown University Hospital in the 1940s, visitors would sometimes bring a jug of spring water to aid a patient’s recovery.

Although Dr. S. T. Carl argued the need for a sanitarium, one was never built. Nor was there a bathhouse in town. Siloam’s water was for drinking, not for medicinal bathing. Even as “taking the waters” fell out of fashion in the 1910s, the town continued to attract visitors. Tourism finally slowed during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Today the springs and their parks are part of a revitalizing downtown. The annual Dogwood Festival is held at City Park, while both parks are favorite photo-taking destinations for high school seniors and prom-goers.

“I came here fifteen years ago suffering with dropsy and heart trouble. Couldn’t walk a hundred yards without sitting down and panting like a lizard. When I came, I was just a ‘witchy old woman’. . . In a month’s time I was very much improved, and in two months I was climbing all over the mountains with my gun, hunting.”

G. Salisbury

Siloam Springs Democrat

December 23, 1898

83-302-80

Siloam Spring, mid 1880s. In 1882 a stone wall was built to house the pipework needed to channel the spring’s water into three spouts. The wall was redesigned by 1897 and remains today, although little water flows from the spring. J. E. Suttle, photographer. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-302-80)

83-302-79

Twin Springs, early 1890s. The sign on the tree warns of a $5 fine for a person washing their hands or face in the water. Clean water was important to combat the spread of disease and protect the town’s health-based industry. Protective reservations restricting development were often placed around springs. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-302-79)

82-193-30

Twin Springs, 1900s. Rockwork from the 1880s may still form a portion of the spring’s enclosure, which was redesigned into an arc shape around 1900. The low wall in front kept Sager Creek from flooding Twin Springs. Little water flows from the springs today. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-193-30)

83-145-6

Band concert, City Park, circa 1910. Sunday afternoons were a time of rest and relaxation, which included strolls through the parks and carriage rides in the country, including day trips to nearby Dripping Springs and its 77-feet tall waterfall (now part of Natural Falls State Park, Oklahoma). Bernice Freeze Collection (S-83-145-6)

83-115-33

Twin Springs Park, late 1910s. The park was once called the “Isle of Patmos” after the Greek island where the apostle John received a vision. The garden and a nearby vine-covered rockwork fountain were installed around 1913. The garden still exists, as does a newer fountain. Maggie Smith Collection (S-83-115-33)

Siloam Springs Photo Gallery

Siloam Spring, mid 1880s. In 1882 a stone wall was built to house the pipework needed to channel the spring’s water into three spouts. The wall was redesigned by 1897 and remains today, although little water flows from the spring. J. E. Suttle, photographer. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-302-80)

Twin Springs, early 1890s. The sign on the tree warns of a $5 fine for a person washing their hands or face in the water. Clean water was important to combat the spread of disease and protect the town’s health-based industry. Protective reservations restricting development were often placed around springs. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-302-79)

Twin Springs, early 1900s. Rockwork from the 1880s may still form a portion of the spring’s enclosure, which was redesigned into an arc shape around 1900. The low wall in front kept Sager Creek from flooding Twin Springs. Little water flows from the springs today. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-193-30)

Band concert, City Park, circa 1910. Sunday afternoons were a time of rest and relaxation, which included strolls through the parks and carriage rides in the country, including day trips to nearby Dripping Springs and its 77-feet tall waterfall (now part of Natural Falls State Park, Oklahoma). Bernice Freeze Collection (S-83-145-6)

Twin Springs Park, late 1910s. The park was once called the “Isle of Patmos” after the Greek island where the apostle John received a vision. The garden and a nearby vine-covered rockwork fountain were installed around 1913. The garden still exists, as does a newer fountain. Maggie Smith Collection (S-83-115-33)

Sulphur Springs — Benton County

“There was a time in the history of this section when the people drank more whisky than water. Now they drink more water than whisky.”

Sulphur Springs Journal

August 28, 1908

In the late 1870s, a few cabins were built to house health seekers visiting the Limestone (later called Iron, Nitre, and Lithia) and White Sulphur Springs located on the Whinnery family farm. When Charles H. Hibler of Missouri saw the valley in 1884, he decided to build a health resort. Using his father’s money he bought the property, sought investors, laid out the town site, and built the Park Hotel and bathhouse. Additional mineral springs were found and Hibler built a park to showcase the waters. According to local advertising, white sulphur water was good for liver problems and black sulphur for malaria, while lithium soothed the nerves and alkaline magnesium helped with intestinal issues.

What would eventually become the Kansas City Southern Railroad arrived in 1891. For a time Sulphur Springs was the end of the line; when the railroad built further south a few years later, visitors followed the line to Siloam Springs and its health offerings. In the 1899 Dun Rating Book, which assessed business and financial information, the town was proclaimed the “neatest, most cleanly kept town in Benton County.” Sulphur Springs was the third most popular resort in Arkansas, after Eureka Springs and, further south, Hot Springs.

Advertisements proclaimed the town as “The Jordan River of Arkansas” and its waters as “Fountains of Youth.” Excursion trains were a weekly event, delivering thousands of visitors each summer. There were many amusements for guests, including assemblies held as part of the national Chautauqua movement, aimed to educate and entertain adult audiences. In the early 1900s the town had eleven hotels, three sanitariums, and numerous doctors.

Working-class coal and lead miners from southwest Missouri came to Sulphur Springs for day excursions. Wealthy investors sought a more exclusive clientele, one which would stay for a longer time. In 1909 Oscar Kihlberg and the other the organizers of the Sulphur Springs Resort and Bath Company opened the grand, five-story, 100-room Kihlberg Hotel with a gala banquet and formal ball.

As the health era faded in the 1910s, the town rebranded itself. The Ozark Colony was formed in 1921 as a self-supporting home colony. Folks were encouraged to build homes, plant fruit crops for income, and engage in various cultural endeavors. The Burger Bathhouse with its hot sulphur water baths was a draw in the 1930s. But the town’s population continued to decline. The springs and many of the original downtown buildings, including the Kihlberg, still stand today. The Burger Bathhouse now houses the Sulphur Springs Community Museum.

[The] “medicinal waters of Sulphur Springs are unexcelled, the place is essentially a health resort and will be such when its several less favorite sisters [other resorts] cease even to lay claim to the honor.”

Sulphur Springs Record

July 16, 1910

86-121-26

Entrance to the city park, 1900s. The park held three of the town’s four mineral springs. Visitors could enjoy the plunge (swimming pool), a baseball lawn and tennis grounds, bathhouses, and promenade grounds. The park is still used today for play, barbeques, and impromptu yard sales. Mrs. Bobbie Kennard Collection (S-86-121-26)

82-170-64

Pavilions for the black sulphur, white sulphur, and magnesia springs, circa 1912. A lithia spring, said to strengthen the muscular and nervous systems, is located on the north end of the park, across Butler Creek. The construction of a nearby water tower in the 1970s has impacted the spring’s water flow. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-170-64)

82-213-61

Mountain View Hotel (formerly the Kihlberg Hotel), mid 1910s. The Kihlberg changed hands several times before John E. Brown bought it and opened a Christian school. A fire in 1940 destroyed the top half of the building. In later years the structure housed the Wycliffe Bible Translators and was part of the campus of the Shiloh Farms Community, a self-sustaining, non-denominational Christian organization. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-213-61)

83-116-81

Boating on Lake LaBalladine, circa 1910. Butler Creek was dammed to form a small lake. A boathouse was built and folks liked to dive off the dam. The high ground at the center of the lake was known as Amusement Island and included a roller skating and dancing pavilion. Benton County Historical Society Collection (S-83-116-81)

86-121-25

Griffin Drug Store and sanitarium, circa 1910. In 1909 Dr. John Morse Griffin and his wife Emma formed the Sulphur Spring Sanitarium Company to treat the infirm. They also formed the Sulphur Springs Mineral Water Company to bottle and ship mineral and carbonated water. Mrs. Bobbie Kennard Collection (S-86-121-25)

96-80-281

Burger Bathhouse sign, with intentional misspellings for “tubbed” and “rubbed,” 1930s–1940s. Frank and Ann Burger built their bathhouse in the 1920s, offering hot and cold black sulphur-water baths, salt rubs, massages, and electric treatments. Frank attended the men while Ann helped with the women. Hazel McGowen Stotler Collection (S-96-80-281)

86-192-1

Visitors at the magnesia and white sulphur springs, 1920s. In 1924 evangelist John E. Brown of Siloam Springs bought most of Sulphur Springs, including the city park, to form a campus for John Brown University, a four-year vocational college. Two years later it was reorganized as a women’s college, but closed in 1928. Jim Buckley Family Collection (S-86-192-1)

Sulphur Springs Photo Gallery

Entrance to the city park, 1900s. The park held three of the town’s four mineral springs. Visitors could enjoy the plunge (swimming pool), a baseball lawn and tennis grounds, bathhouses, and promenade grounds. The park is still used today for play, barbeques, and impromptu yard sales. Mrs. Bobbie Kennard Collection (S-86-121-26)

Pavilions for the black sulphur, white sulphur, and magnesia springs, circa 1912. A lithia spring, said to strengthen the muscular and nervous systems, is located on the north end of the park, across Butler Creek. The construction of a nearby water tower in the 1970s has impacted the spring’s water flow. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-170-64)

Mountain View Hotel (formerly the Kihlberg Hotel), mid 1910s. The Kihlberg changed hands several times before John E. Brown bought it and opened a Christian school. A fire in 1940 destroyed the top half of the building. In later years the structure housed the Wycliffe Bible Translators and was part of the campus of the Shiloh Farms Community, a self-sustaining, non-denominational Christian organization. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-213-61)

Boating on Lake LaBalladine, circa 1910. Butler Creek was dammed to form a small lake. A boathouse was built and folks liked to dive off the dam. The high ground at the center of the lake was known as Amusement Island and included a roller skating and dancing pavilion. Benton County Historical Society Collection (S-83-116-81)

Griffin Drug Store and sanitarium, circa 1910. In 1909 Dr. John Morse Griffin and his wife Emma formed the Sulphur Spring Sanitarium Company to treat the infirm. They also formed the Sulphur Springs Mineral Water Company to bottle and ship mineral and carbonated water. Mrs. Bobbie Kennard Collection (S-86-121-25)

Burger Bathhouse sign, with intentional misspellings for “tubbed” and “rubbed,” 1930s–1940s. Frank and Ann Burger built their bathhouse in the 1920s, offering hot and cold black sulphur-water baths, salt rubs, massages, and electric treatments. Frank attended the men while Ann helped with the women. Hazel McGowen Stotler Collection (S-96-80-281)

Visitors at the magnesia and white sulphur springs, 1920s. In 1924 evangelist John E. Brown of Siloam Springs bought most of Sulphur Springs, including the city park, to form a campus for John Brown University, a four-year vocational college. Two years later it was reorganized as a women’s college, but closed in 1928. Jim Buckley Family Collection (S-86-192-1)

Other Notable Springs

Benton County

Cherokee City

Cherokee City lies along the western border of Benton County, next to what was Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The town site was surveyed in 1880 and over the next two years the area boomed as a summer resort, based on its springs. A hotel was erected, as were small, quickly built structures to meet the lodging needs of health seekers.

In 1882 resident John D. Hood described Cherokee City as thriving, with a population of around 300 to 400. “People visit [the medicinal spring] from all parts of the United States for their health.” Of the area, he said, “The people all look healthy and the society is good.”

For whatever reason, Cherokee City’s health industry quickly went from boom to bust. The town survived for a time as a frontier trading post and as a supplier of whisky to the neighboring Indian tribes. Just a few dozen folks live there today.

“. . . we turned our course south taking the line road for Cherokee City, another of the watering places of Benton county. Eight miles over a fine road and some nice country brought us to the Cherokee City springs, where we found plenty of water and forty or fifty campers. This is a pleasant place. Mr. Rich is the owner of the land and general proprietor of the place. Lots were to be laid off on the following Monday and put on the market.”

Fayetteville Democrat

July 24, 1880

Eldorado

In 1879 Ambrose T. Hedges homesteaded a number of acres in what would become Eldorado. He transferred the property to the Eldorado Spring Town Company in 1880. It seems likely the investors were hoping to mimic the success of Eureka Springs. And naming the place after the legendary Spanish city of gold was sure to impress. Company president Dr. C. F. Baker had the spring’s water tested. A trace amount of arsenic was found which, at the time, was thought to have healing properties.

Land was platted and lots were sold. Various businesses and several doctors moved to town. A six-room boarding house was built and, as the town grew, a multistory hotel was added to the hillside. Water was bottled and shipped out. New springs were dug at the base of the hills and walled with stone. Advertisements were sent to large newspapers on the East Coast. A post office was established under the name Pactolus, as Arkansas already had a town called El Dorado. The population grew to 1,500 in 1883. In 1883 or 1884, water from Spavinaw Creek flooded the valley town, destroying most of the buildings and causing many residents to move away. In the early 1900s the post office closed and the large hotel was torn down. Today only a few fragments remain of Eldorado.

“There are fifty two houses completed, ten in course of construction, about fifteen or twenty tents and a population of about three hundred and fifty. . . . The place gives many evidences of success.”

Fayetteville Democrat

July 24, 1880

Electric Springs

Electric Springs Hotel, circa 1890. The hotel was built in 1888 by the Frisco to encourage passenger traffic to Rogers. Guests were driven from the depot in carriages to “Horsely’s Hotel,” run by William Horsely. The building was torn down in the early 1940s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4812)

Electric Springs was laid out in 1881, with over 550 lots for building, just northeast of the new town of Rogers. In 1888 the San Francisco-St. Louis Railway Company (the “Frisco”) saw the commercial potential of a spring located near its Rogers railroad depot. In hopes of providing business for the railroad, the Frisco built a large hotel. Several cottages were also erected.

As the wonder of commercial electricity became available during the late 19th century, electrotherapy and electromagnetism treatments came into vogue. The spring may have been named to cash in on the popularity of electric medicine or because of its reputed ability to magnetize metal. In 1897 a St. Louis chemist analyzed the water and declared it good for “sties [inflamed swelling of the eyelid], carbuncles [a severe boil in the skin], boils, internal abscess, glands, liver diseases, scrofula [glandular swelling], rheumatism, indigestion and constipation.”

Electric Springs, circa 1910. N. B. Morton was known as the “Mayor of Electric Springs.” He sold spring water to the citizens of Rogers. His belief in its curative properties was so strong that he said that if the water didn’t cure a body, “something else must be lacking.” Tom P. Morgan, photographer. Bonnie Hanks Collection (S-2000-40-2)

For a time the resort was so popular that visitors came year after year. A horse-drawn carriage ran daily from downtown to the spring. In 1903 the Cottage Hotel was built. Two years later Lena Fuller, a nurse, and Dr. W. L. Leister opened the Electric Springs Sanitarium, conducting it “as a resort for the scientific treatment of diseases.” Leister was an Eclectic physician and medical author. Eclectic medicine developed in the late 19th century as a reaction to traditional medicine’s “barbaric” use of such treatments as purging and bloodletting. It used botanical remedies and other substances to treat patients, along with physical therapy.

While the hotel and sanitarium are long gone, the springs’ stone wall and concrete basins can still be seen along the south side of Highway 12, near Lake Atalanta, about one mile northeast of downtown Rogers.

[The Electric Springs Sanitarium] “ . . . is located in a wooded valley surround by mountains, whose sides are covered with beautiful forestry. It is isolated, yet hard-by electric springs—three phenomenal streams of medicinal cold water spurting from the base of West Mountain. An ideal retreat, all in the heart of the Ozark Mountains, in a climate cooler in summer than a hundred of miles further north, and warmer in winter than western Texas.”

Dr. W. L. Leister

The Eclectic Medical Journal

May 1905

Park Springs

Field Bohart with friend, early 1900s. The rock-covered spring is seen at top center. A metal pipe discharges water near the end of the bridge. In later years, a sign proudly announced the spring’s radioactivity. Monte Harris Collection (S-86-319-10)

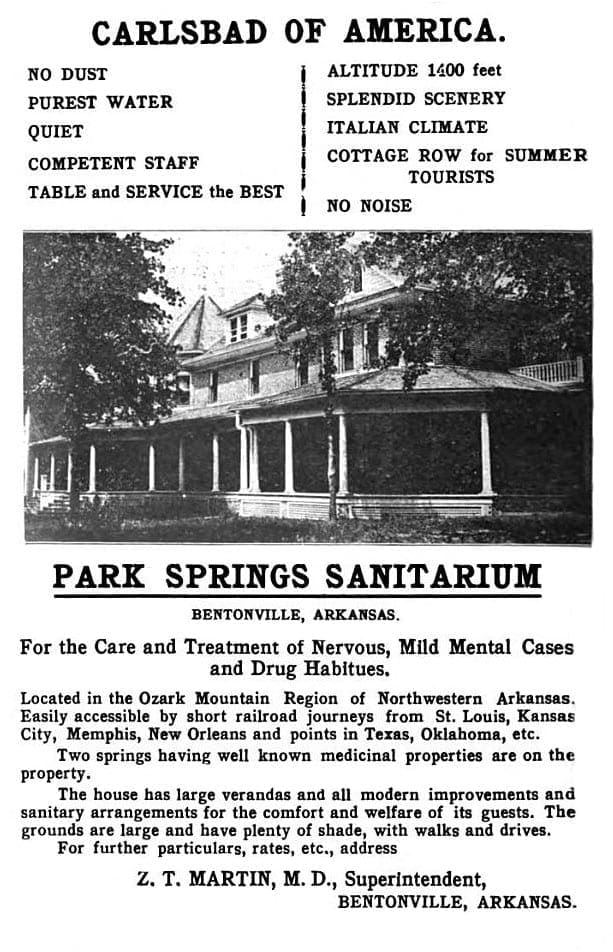

Two small “therapeutic” springs were discovered near downtown Bentonville in the 1890s. In 1910 A. T. Still opened the 42-room Park Springs Sanitarium. An ad in a psychiatric medical journal touted the sanitarium as the “Carlsbad of America,” offering to treat “nervous, mild, mental cases and drug habitués.”

J. D. Southerland purchased the building in 1913 and turned it into the Park Springs Hotel, a summer resort where families could “escape the hot weather in the cities.” Southerland also owned the short-lived interurban, a type of streetcar that provided passenger service from the Frisco depot in Rogers to downtown Bentonville and the hotel.

Park Springs was promoted as having radioactive water which could treat diabetes, rheumatism, and diseases of the stomach, kidney, and bladder. Treatment involved “drinking, inhalation of steam or vapors, douches, irrigation of accessible organs” and external application by shower, water pack, or bathing. A 1920s advertisement promoted the water’s combination of radium and lithium, describing the taste as “simply delicious” and that “one can drink all one wants without injury.” It goes on to say that radium “is conceded by the medical profession to be one of the greatest curative elements ever discovered.”

Rendering of the Park Springs Sanitarium by the St. Louis architecture firm of Matthews & Clarke, circa 1910. A. O. Clarke designed many notable area buildings including Missouri Row, a log hotel at Monte Ne. Although the resort included springs named Elixir and Lithia, it rarely advertised itself as a health destination. Tom Duggan Collection (S-2008-5-1)

Southerland experienced financial troubles and sold the property to George and Clara Crowder, who operated the resort until 1924. Over the years the building was used for nursing homes and Christian colleges. It was torn down in the 1960s or 1970s. Park Springs Park is located at 300 NW 10th Street. The 18-acre park includes the springs, a playground, a small pavilion for gatherings, and the Burns Arboretum/Nature Trail.

Boone County

Elixir Spring

“The town at present contains 100 neat, commodious and comfortable business houses and residences, all of which are filled by a sturdy and moral people, most of whom are receiving lasting benefits from the many health-giving springs. The main springs are well protected by large reservations or parks, all of which are covered with a dense growth of native timber and are guarded with the jealous eyes of the citizens.”

Elixir Bugle

March 24, 1883

Elixir Spring lies in the pine-covered hills of Elixir Valley. It was discovered high up on the mountainside under a large bluff, by a farmer looking for stray cattle. He drank the water, found it soft and sweet tasting, and continued to drink, day after day. Much to his surprise, he was cured of a stomach ailment. Sharing the news of his discovery in Harrison, several men decided to invest in a health resort.

In 1880 the town was laid out into 129 blocks with roughly 1,000 lots. Homes and businesses were erected, including three large, three-story hotels built into the hillsides—the Singletary, the Ladd, and the Stillwell. Within a few years the town boasted hundreds of residents. The Elixir Bugle newspaper was established and the Elixir Institute began holding classes in September 1882. Additional springs were discovered and named, including Medica, Sulphur, and Tonic.

To ensure its success, Elixir leaders worked to bring a railroad to town. Surveying parties came and marked right-of-ways, building up residents’ hopes, but nothing came of it. The town was too far off the beaten path. Folks began to move away and the school closed. By 1892 Elixir Springs was nearly a ghost town.

“I was brought to the Springs in a helpless condition with heart disease. My treatment was Elixir water. In three months I could walk and my health was restored.”

Rachel Willis of Oregon, Arkansas

Elixir Bugle

May 5, 1883

Madison County

Aurora

In the early 1880s, the chalybeate (iron) springs on Grand Mountain were found to have medicinal properties. A two-story hotel was built, along with a few small log homes. During the summer, tents were erected beneath the trees. Stone steps were laid around the spring to afford health seekers a place to sit while they took the water.

In the late 1920s Jim Parker, whose family owned the spring, wrote that “Pure mountain air and rest beneath the shade of the trees gave relief from chills and malaria fever, and many lame-backed old men insisted that the water was a sovereign remedy for kidney troubles.” It’s unclear how long the hotel lasted, but the Parker family retained their old house near the spring, saying, “Who knows but this place may again have value as a health resort?”

Today the hotel is long gone but the spring remains. It’s located on private property on the side of a steep hill, protected by a small, stacked rock enclosure. Stone steps, now buried under years of soil and leaves, once gave visitors access to the water. For many years a dipper was kept at the spring for passersby. Just below the spring is a concrete-block trough. Water from the spring drips into it, depositing dissolved iron, seen as a reddish-brown substance.

St. Paul

In 1886 Hugh F. McDanield began building a railroad east from Fayetteville to St. Paul, to take advantage of the area’s vast timber resources. On a mountaintop south of town stood a tall sandstone rock formation called “Chimney Rock.” Three springs were found near the outcropping, at the base of several large boulders.

When McDanield learned of the springs he had the water tested and was told they had medicinal qualities. He decided to build a hotel like the Crescent Hotel in Eureka Springs, hoping to turn St. Paul into a tourist destination. Such an elegant hotel “would add a touch of polish to the rawness and clamor of the busy new town.” Bluegrass seed was sown, a thirteen-acre game preserve was set aside, a road was begun, and blueprints for the hotel were drawn by a St. Louis architect. Three railroad carloads of pipe meant to carry water from the springs were delivered to the foot of the mountain, but McDanield’s death in 1888 ended the venture. The pipe lay there for years, rusting away. Remnants of it could still be seen in the 1960s.

“Oh! how all blossoming things would revel if planted and cared for here! What hanging gardens of delight could be made on this mountain side! . . . I hope and wish that every word I have heard of Mr. McDanield’s plans for this mountain may be true, and that they may perfectly succeed. I think that it is not only well calculated for a summer resort from the crowded cities, but for a winter resort for invalids and others wishing to escape northern winters, and for a resting place for the over-worked and world-weary.”

St. Paul Republican

November 12, 1887

Newton County

Tom Thumb Spring

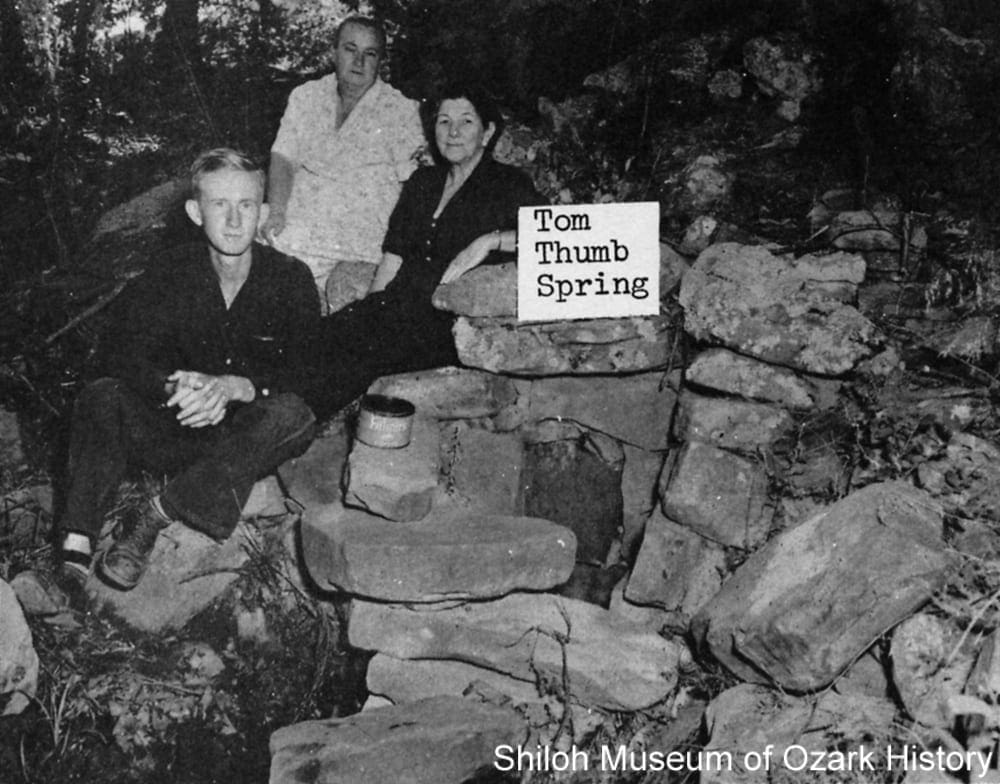

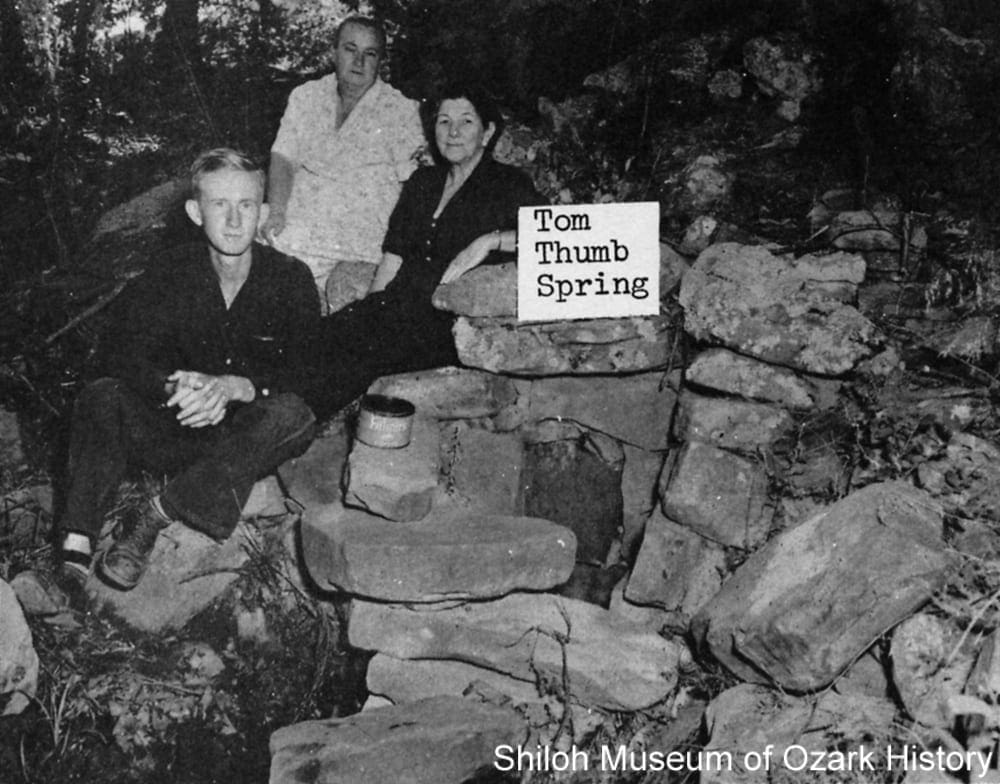

Hackler or Hatfield family at Tom Thumb Spring, 1950s. During the 20th century the Hackler family got their water supply from the spring; the Hatfields lived nearby. In 1961 Rev. C. H. Hatfield wrote, “This spring is not as bold as it used to be, but its mineral content is great.” Benton County Pioneer, November 1962.

David Wilbur Beck’s ambition was to be a physician and to have a health resort. In the early 1840s he learned of a group of explorers from the Gaither Cove community in Boone County who had traveled to a remote spring just over the Newton County line to collect water to treat an outbreak of malaria. While there they met a small man who went by the name of Tom Thumb, who was taking the waters for an ailment.

Sensing an opportunity, Beck hired men at 25 cents per day to build a dormitory near the spring for summer visitors. Beck also built a dog-trot log building; one side was for his family, the other for his doctor’s office. The Becks lived as squatters, hoping to eventually claim the land from the government. One summer Beck’s wife became ill and died of malaria. Beck remarried but his second wife was not enthusiastic about the resort, telling him that “she would not be part of bathing dirty old men for them to try to regain their youth.” Sometime during or after the Civil War bushwhackers raided the property, burning 70 cottages, yet sparing two open-roofed bathhouses and the dormitory. The Becks then abandoned their land.

In the mid 1870s Dr. Thomas Jayland of New York began squatting near the spring. A botanist and a Quaker, Jayland administered his herbal medicines for free. At its peak the population at the spring reached around 400 to 500 folks, with most camping for a short time while they took the waters. He told visitors they were welcome to build houses and that he would give them their home site, once he received his land patent. Several cabins belonged to doctors and preachers.

Although Jayland was said to be adverse to money, in 1880 he sold his homestead near the spring to a Mr. Brisco, whose brother ran the health spa. Jayland went back on his promise to deed the land to the homebuilders, claiming that God wouldn’t like his gift to the world to be commercialized. This angered folks and many left. One night Jayland’s cabin was doused with oil and set on fire. The doctor escaped and moved away. By 1883 only a few souls lived at the spring. Today the spring is enclosed, serving as a water supply for the owners of the property.

Tom Thumb Spring

Hackler or Hatfield family at Tom Thumb Spring, 1950s. During the 20th century the Hackler family got their water supply from the spring; the Hatfields lived nearby. In 1961 Rev. C. H. Hatfield wrote, “This spring is not as bold as it used to be, but its mineral content is great.” Benton County Pioneer, November 1962.

David Wilbur Beck’s ambition was to be a physician and to have a health resort. In the early 1840s he learned of a group of explorers from the Gaither Cove community in Boone County who had traveled to a remote spring just over the Newton County line to collect water to treat an outbreak of malaria. While there they met a small man who went by the name of Tom Thumb, who was taking the waters for an ailment.

Sensing an opportunity, Beck hired men at 25 cents per day to build a dormitory near the spring for summer visitors. Beck also built a dog-trot log building; one side was for his family, the other for his doctor’s office. The Becks lived as squatters, hoping to eventually claim the land from the government. One summer Beck’s wife became ill and died of malaria. Beck remarried but his second wife was not enthusiastic about the resort, telling him that “she would not be part of bathing dirty old men for them to try to regain their youth.” Sometime during or after the Civil War bushwhackers raided the property, burning 70 cottages, yet sparing two open-roofed bathhouses and the dormitory. The Becks then abandoned their land.

In the mid 1870s Dr. Thomas Jayland of New York began squatting near the spring. A botanist and a Quaker, Jayland administered his herbal medicines for free. At its peak the population at the spring reached around 400 to 500 folks, with most camping for a short time while they took the waters. He told visitors they were welcome to build houses and that he would give them their home site, once he received his land patent. Several cabins belonged to doctors and preachers.

Although Jayland was said to be adverse to money, in 1880 he sold his homestead near the spring to a Mr. Brisco, whose brother ran the health spa. Jayland went back on his promise to deed the land to the homebuilders, claiming that God wouldn’t like his gift to the world to be commercialized. This angered folks and many left. One night Jayland’s cabin was doused with oil and set on fire. The doctor escaped and moved away. By 1883 only a few souls lived at the spring. Today the spring is enclosed, serving as a water supply for the owners of the property.

Washington County

Salem Springs

Salem Springs was first settled in the early 1830s, before Arkansas statehood. Located along the border of then Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), it served as a trading post for many years. It was renamed Sexton in 1882 with the establishment of a post office. At that time promoters boasted about the healing powers of the town’s three springs which emerged from a bluff and were channeled ten feet down to the valley floor via a wood trough. The water from each spring was said to have been a different temperature, although they were all within a few feet of one another.

Boosters claimed that the springs were equal or superior to other medicinal springs and that Sexton’s location was better in many ways than that of Eureka Springs and Siloam Springs. The springs were said to help cure “scrofula, rheumatism, scald head, dyspepsia, liver complaint and cancerous affectation.” According to an 1882 news article, Mrs. Deal of Humboldt, Kansas, ” . . . commenced using the water in September last, and a few weeks ago the cancer all came out and is rapidly healing up.”

At first, health-seekers camped near the spring in the summertime. Then Russell Bates built a two-story hotel for those taking the waters and enjoying the “invigorating Ozark Mountain air.” He later sold the hotel to Ben Fields. The town, which had hopes of being the next Eureka Springs or Siloam Springs, began to fade away in the early 1900s after being bypassed by two railroads. Today the spring still flows down the bluff into a plastic trough, but all that’s left of Sexton is one old home.

“Reverend Gamaliel Bryant of Goshen . . . could hardly walk when he went to Salem . . . and to convince us that he had been greatly benefitted he jumped up and cracked his heels together like a lad of 16, although he is some 65 years of age.”

Fayetteville Democrat

June 21, 1883

Sulphur City

Springhouse at Sulphur City, 1922. The sulphur spring was located on the bottom level of the structure, within an open-air pavilion. This configuration likely helped vent the water’s strong smell. Over the years the springhouse was used as a community building. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-721)

Located near the Middle Fork of the White River, the Sulphur City community was first called Mankins after a local family. Hearing the news of Eureka Springs’ prosperity, entrepreneurs renamed the town Sulphur Springs, only to change it to Sulphur City when they discovered the former name was taken. Promoters said the spring was good for gout, dyspepsia (indigestion), cancer, rheumatism, and other ailments.

Expecting prosperity, a springhouse and guest cottages where built in the early 1880s. North of the spring the land was sectioned into 24 blocks, each with 12 lots. Dr. John C. Carter prepared to administer bloodletting and other treatments to patients at his nearby office. A “large and beautiful park” and a hotel to be supplied with spring water was planned for, but never built. Remarking on the lack of progress, George Van Hoose, the Sulphur City correspondent for a Fayetteville newspaper, wrote, “The timbers of the hotel remain growing in the forest.”

At the spring, water first trickled into a triangular basin which was so small, that only one foot could be bathed at a time. The basin was eventually enlarged to hold about five gallons of water, taking an hour or so to fill. Below, a bathing “tub” was carved from rock.

The resort never took off. Patients would have had to travel ten or more miles by horse from Fayetteville or Elkins over rough country roads. The spring produced little water, perhaps another reason for the resort’s failure.

Today a tumbled stone wall and scattered rockwork can be found in the woods along County Road 57, just east of the Whitehouse Road intersection, across from the Sulphur City Baptist Church. Water still seeps from the spring, leaving a whitish residue on the ground and a strong, sulphurous smell in the air. Dr. Carter’s office has been relocated to the grounds of the Shiloh Museum.

“The spring is of the kind generally known as the ‘white sulphur’ because of the white deposit left by the water upon any surface over which it flows. The water is very strongly impregnated with gas, as is evidence by the marked odor perceived on approaching the spring . . . About a quarter mile [away] . . . is located what has been known as the ‘Selzer Spring,’ which is reported to be valuable, especially in cases of female trouble.”

Fayetteville Democrat

January 19, 1882

Sulphur City—Washington County

Springhouse at Sulphur City, 1922. The sulphur spring was located on the bottom level of the structure, within an open-air pavilion. This configuration likely helped vent the water’s strong smell. Over the years the springhouse was used as a community building. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-721)

Located near the Middle Fork of the White River, the Sulphur City community was first called Mankins after a local family. Hearing the news of Eureka Springs’ prosperity, entrepreneurs renamed the town Sulphur Springs, only to change it to Sulphur City when they discovered the former name was taken. Promoters said the spring was good for gout, dyspepsia (indigestion), cancer, rheumatism, and other ailments.

Expecting prosperity, a springhouse and guest cottages where built in the early 1880s. North of the spring the land was sectioned into 24 blocks, each with 12 lots. Dr. John C. Carter prepared to administer bloodletting and other treatments to patients at his nearby office. A “large and beautiful park” and a hotel to be supplied with spring water was planned for, but never built. Remarking on the lack of progress, George Van Hoose, the Sulphur City correspondent for a Fayetteville newspaper, wrote, “The timbers of the hotel remain growing in the forest.”

At the spring, water first trickled into a triangular basin which was so small, that only one foot could be bathed at a time. The basin was eventually enlarged to hold about five gallons of water, taking an hour or so to fill. Below, a bathing “tub” was carved from rock.

The resort never took off. Patients would have had to travel ten or more miles by horse from Fayetteville or Elkins over rough country roads. The spring produced little water, perhaps another reason for the resort’s failure.

Today a tumbled stone wall and scattered rockwork can be found in the woods along County Road 57, just east of the Whitehouse Road intersection, across from the Sulphur City Baptist Church. Water still seeps from the spring, leaving a whitish residue on the ground and a strong, sulphurous smell in the air. Dr. Carter’s office has been relocated to the grounds of the Shiloh Museum.

“The spring is of the kind generally known as the ‘white sulphur’ because of the white deposit left by the water upon any surface over which it flows. The water is very strongly impregnated with gas, as is evidence by the marked odor perceived on approaching the spring . . . About a quarter mile [away] . . . is located what has been known as the ‘Selzer Spring,’ which is reported to be valuable, especially in cases of female trouble.”

Fayetteville Democrat

January 19, 1882

Sights and Sounds from Area Springs

Credits

Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission. “Karst Topography in the Arkansas Ozarks.” https://www.naturalheritage.com/_literature_128222/Karst_in_the_Arkansas_Ozarks (accessed 10-4-2020)

Arkansas Gazette. “Siloam Springs: The Range and Possibilities of These Famous Northwestern Waters—The Population of the Place next to Hot Springs and Eureka.” 12-8-1881, as reprinted in Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 20, No. III (Summer 1975).

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. “Coon Creek Bridge, Cherokee City, Benton County.” http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/national-register-listings/coon-creek-bridge (accessed 10-4-2020)

Arkansaw (a pen name). Letter to the editor. Fayetteville Daily Democrat, 2-23-1882.

———. “From Salem Springs.” Fayetteville Daily Democrat, 3-16-1882.

Benton County Heritage Committee. History of Benton County, Arkansas. Curtis Media Corp.: Dallas, 1991.

Benton County Pioneer. “Springs in Rogers History.” Vol. 29, No. 2 (Summer 1984).

———. “Sulphur Springs Known as National Health Resort.” Vol. 36, No. 2 (Summer 1991).

Black, J. Dickson. History of Benton County. International Graphics Industries: Little Rock, 1975.

Bowden, Bill. “Controversy dams fix to town’s main spring.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 9-8-2011.

Bullard, Loring. Healing Waters: Missouri’s Historic Mineral Springs and Spas. University of Missouri Press: Columbia & London, 2004.

Carter, Nancy. “New chapter for a storybook hotel.” Green Forest Tribune, 6-6-1983.

Craig, Charlie. “One more time, Sulphur Springs.” Benton County Democrat, 7-3-1988.

———. “Two pools and a hotel.” Benton County Daily Democrat, 8-17-1986.

Crescent Hotel and Spa. “Crescent Hotel History.” http://www.crescent-hotel.com/history.shtml (accessed 10-4-2020)

Eclectic Medical Journal. “The Electric Springs Sanitarium.” Vol. LXV., No. 5 (May 1905).

Feroe, Nancy. (Benton County Historical Society). Conversations and email correspondence with Marie Demeroukas (Shiloh Museum research librarian), April 2014.

Froelich, Jacqueline. “Eureka Springs in Black and White: The Lost History of an African-American Neighborhood.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LVII, No. 2 (Summer 1997).

Garza, Midge. “Springs bring tourism.” Rogers Daily News, 5-28-1981.

Goodspeed’s 1889 History of Benton County. Goodspeed Publishing Co.: Chicago, 1889.

Gravette News Herald. “The Death of a Spring.” 7-15-2009.

Guccione, Margaret J. “Geologic History of Arkansas Through Time and Space.” Arkansas Geological Survey, 1993. https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/docs/pdf/education/geologic-history-of-arkansas-through-time-and-space-gray-scale.pdf (accessed 10-4-2020)

Hadley, Marge. Di-Goh-Doo-Nah-I, West of the Tracks, Northwest Benton County. Print Shop Press: Gravette, AR, 1990.

Hardaway, Billie Touchstone. These Hills, My Home—A Buffalo River Story. Western Printing Co.: Republic, MO, 1980.

Harington, Donald. Let Us Build Us a City. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich: New York, 1986.

Harris, Monte. “Calahan’s Station.” Rogers Historical Museum. https://rogersar.gov/DocumentCenter/View/339/Callahans-Station-PDF (accessed 10-4-2020)

———. Email correspondence with Marie Demeroukas (Shiloh Museum research librarian), April 2014.

Hilton, Burline. “Old Salem Springs (Sexton).” Flashback, Vol. XIX, No. 1 (February 1969).

Historic Washington County Arkansas. “Salem Springs. ” http://www.historicwashingtoncounty.org/salemsprings.html (accessed 10-4-2020)

Hood, John D. “A Letter from Arkansas.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Winter 1977).

Huff, J. Roger, compiler. “The Lost Town of Eldorado.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Winter 1982).

Hughes, Charles H., ed. The Alienist and Neurologist—A Journal of Scientific, Clinical and Forensic Neurology and Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuriatry. Vol. XXXII, No. 2 (May 1910).

Idaho Museum of Natural History. “What is an Aquifer?” http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/hydr/concepts/gwater/aquifer.htm (accessed 10-4-2020)

John Brown University. “Timeline: JBU through the Years.” http://www.jbu.edu/archives/timeline/ (accessed 10-4-2020).

Kalklosch, L. J. The Healing Fountain, Eureka Springs, Ark., A Complete History. Eureka Springs, 1881.

Lancaster, Guy. “Sulphur Springs. ” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=6176 (accessed 10-4-2020)

Logan, Roger V. Jr., editor. “Elixir Springs, Arkansas,” Mountain Heritage: Some Glimpses into Boone County’s Past After One Hundred Years. Times Publishing Co.: Harrison (Arkansas), 1969.

Palace Hotel and Bath House Spa. “Hotel History.” http://www.palacehotelbathhouse.com/hotel_history.html (accessed 10-4-2020).

Plank, Will. “The Sulphur Springs Record.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 2, No. 5 (July 1957).

Precht, Marla. “Lithia’s Lament.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 30, Nos. 2 & 3 (Mar-Apr 1982).

Rafferty, Milton. “Ozarks Health Spas and Springs. ” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 27, No. 1(Jan-Feb 1979).

Reece, Randy. “Multitude of towns came and went.” Benton County Daily Record, 1-26-1986.

Rogers Daily News. “Sulphur Springs’ Water Attracts Many Tourists. 7-24-1966.

Rose, Sammie, and Pat Wood. “Tom Thumb Spring and the Needle’s Eye.” Boone County Historian, Vol. XIV, No. III (July-September 1991).

Rose, Terry. “Where’s Salem?” Westville (Oklahoma) Reporter, 12-15-2005.

Russell, Conrad. “History of Sexton or Salem Springs.” Prairie Grove Enterprise, 10-22-1987 or 1989.

Russell, Joy (Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society). Conversations and email correspondence with Marie Demeroukas (Shiloh Museum research librarian) April/May 2014.

———. Stepping Back Into Time: St. Paul, Arkansas, 1886-1937. Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society: Huntsville, Arkansas, 2005.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. Water, Water Everywhere. July 1990.

Siloam Springs Democrat. Untitled news clipping, 12-23-1898.

Silva, Rachel. “Walks through History: Siloam Springs Downtown Historic District,” Rachel Silva, Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 5-14-2011. http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=170861 (accessed 10-4-2020)

Smith, Maggie Aldridge. Hico, A Heritage: Siloam Springs History. Siloam Springs Bicentennial Committee: Siloam Springs (Arkansas), 1976.

Smith, Maggie. Simon Sager Celebration. Cabincraft Book/Simon Sager Press: Siloam Springs (Arkansas), 1986.

St. Paul Republican. “The South Mountain.” 11-12-1887.

Sulphur Springs Centennial Committee. Sulphur Springs, Ark.—1890-1990. Bell Books: Rich Hill, MO, 1990.

United States Geological Survey. “Springs and the Water Cycle.” http://water.usgs.gov/edu/watercyclesprings.html (accessed 10-4-2-2020)

Walker, Leeanna. “Region’s many springs proved drawing card in early part of century.” Rogers Morning News, 6-28-1999.

Warden, Don (Siloam Springs Museum). Conversations and email correspondence with Marie Demeroukas (Shiloh Museum research librarian), April 2014.

Westphal, June, and Kate Cooper. Eureka Springs: City of Healing Waters. The History Press: Charleston, SC, 2012.

Williams, Bill. “Ballyhoo for Salem Springs.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 3-13-1982.

Woods, S. Dee. “Reminiscences of Early Sulphur Springs and Its People.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 5, No. 9 (July 1957).

Young, Aubrey, ed. Sulphur Springs, An Introduction to the Heritage of Our Town. Sulphur Springs Community Museum, 2007.

Zodrow, David. “An Old Town Remembers Its Past. “Northwest Arkansas Times, 9-7-1975.