Ozarks at Play

Online Exhibit

Clyde Barker pushing Wayne Martin in a wheelbarrow, Pettigrew, circa 1940. Wayne Martin Collection (S-99-32-567)

What is play? Merriam-Webster defines it as “the spontaneous activity of children.” The word comes from plega, an Anglo-Saxon word meaning sport or game. While children’s activities are often described as play, similar activities by adults are termed leisure. Recreation is seen as more purposeful and organized, like playing a sport.

The notion and importance of play has changed over the centuries. When Europeans first settled in the New World, they didn’t have time for play. The average child might have a couple of modest, homemade toys—a carved animal, a rag doll—but chores filled up most of the day. Entire families worked at farming, homemaking, and earning a living. This was mostly a matter of survival, but Puritan belief also held that idleness was wrong.

Things started to change in the mid 1800s with the Industrial Revolution. As cities grew and technology advanced, people left the farm to work in factories and at jobs in town. At the end of the long work week, employees were left with a bit of free time. But what to do with it? Progressive-era social reformers promoted leisure activities as a way for the working class to renew their mental and physical energy and connect with family.

Before the Industrial Revolution, children were treated as little adults, wearing similar fashions, working strenuous chores, and being exposed to the same unpleasant realities as grown-ups. As industrialization progressed and affected society, children came to be viewed as innocents needing protection, instruction, and nurturing. Childhood was recognized as a separate phase of life, and toys, fashion, and attitudes changed accordingly.

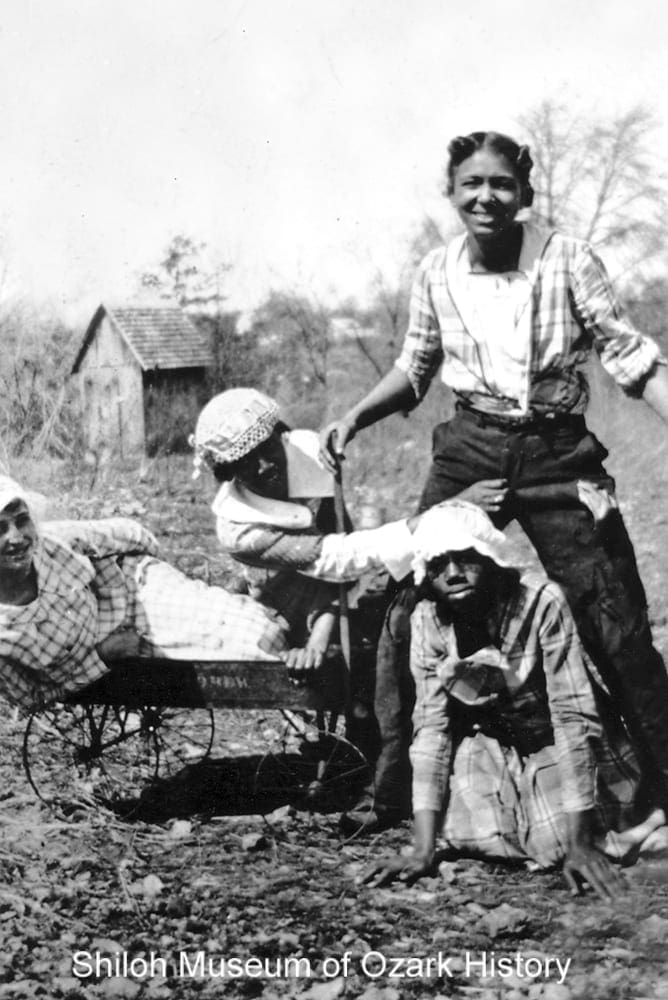

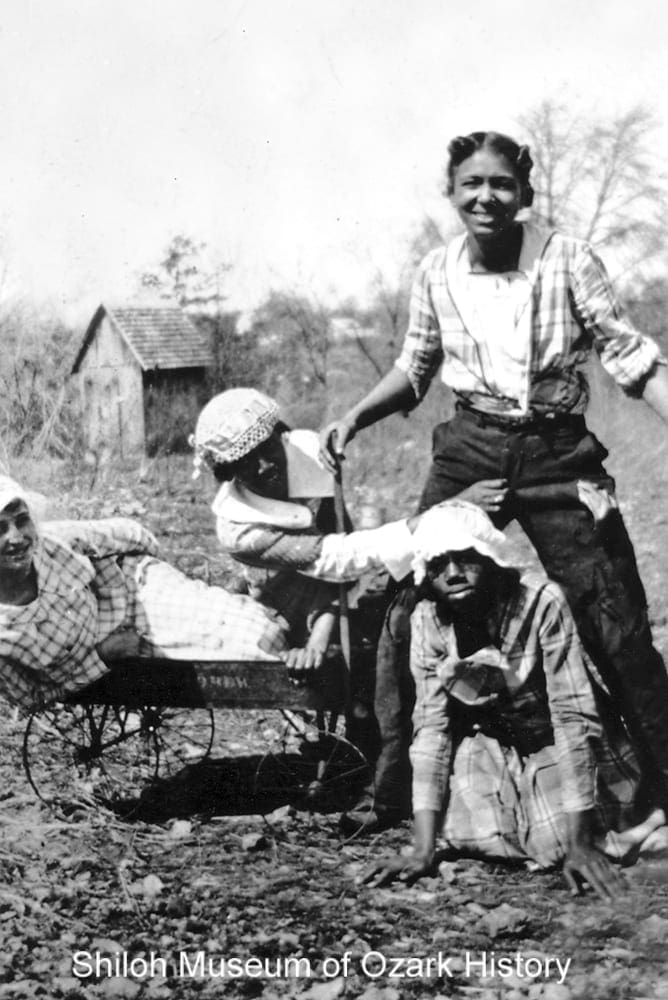

Girls clowning around, Bentonville. From left: Dorothy Love, unidentified, Hattie Finney (standing), and Ora Crawley, 1920s. Jo Hall Collection (S-96-2-64)

At the beginning of the 19th century, adults believed that children’s toys and games should both educate and teach morals. America’s move towards industrialization made toys more plentiful and affordable for the expanding middle class. More toys meant more marketing. Products were designed and sold on an annual cycle, with Christmas as the focal point. By the late 1800s, it was okay for toys to be fun.

The growth of the business world changed society as well, bringing ideas of teamwork and competition to activities such as sports. Leagues were formed, rules were refined, and the strenuous, manly life was promoted. The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was founded in England in 1844 to build character through a variety of means, including athletics. The notion of “muscular Christianity” furthered this idea by equating physical fitness with good morals and a strong nation.

Attitudes towards play changed even further in the 20th century. After World War I adults started participating in their children’s play. Youth culture came into force in the 1950s as television shows and products were marketed to children. By the 1980s scholars started wondering what toys say about us. Do beautiful, shapely dolls make us feel inadequate? Do toy guns and war play decrease our sensitivity to violence?

In many ways, today’s play seems different from earlier generations. Safety concerns keep children nestled safely at home or at sanctioned events, rather than roaming neighborhoods on their own. Activities are highly structured. There are play dates for youngsters, specialty camps for all sorts of pastimes, and numerous after-school activities. Technology and an emphasis on early education have brought computer games that teach toddlers their ABCs.

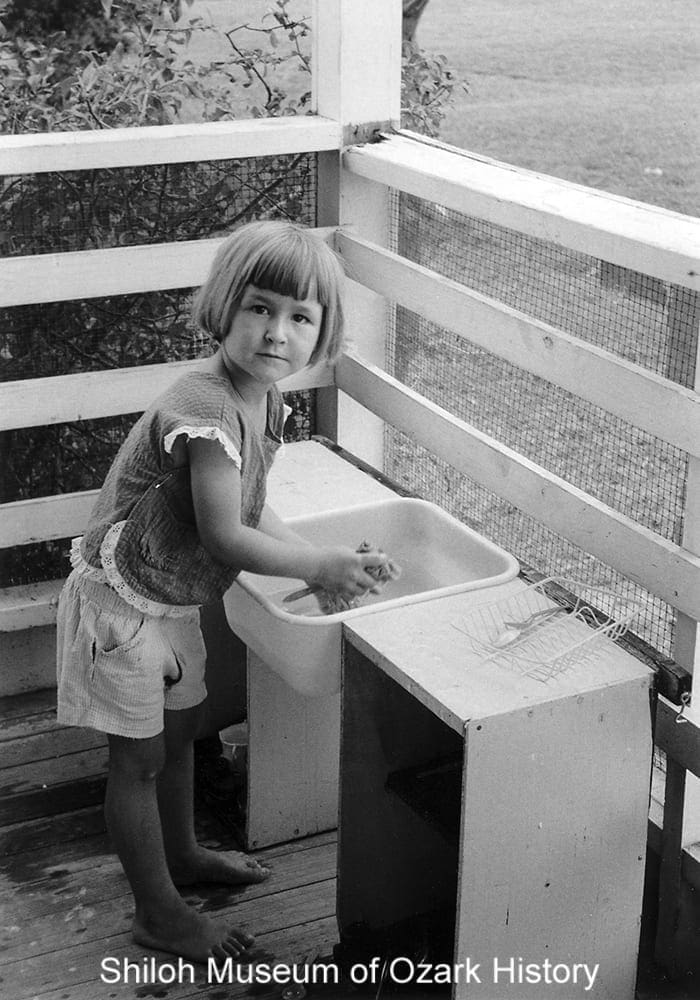

Unidentified girl with dolls, Northwest Arkansas, circa 1910. J. D. Johnson Collection (S-86-122-12)

More and more, children and adults are scheduling play, turning it into a job rather than free-spirited fun. Even dogs have their own play parks and doggie day-care activities. A 2007 study found that one in three American workers don’t take all of their allotted vacation days. And when they do travel, many engage in goal-oriented activities while juggling work-related emails.

So what does the future of play hold? Will we overschedule ourselves, making play a chore rather than a pleasure? Will businesses marketing must-have gear and lifestyles make play too expensive? Will we be harmed by violent, addictive, or dangerous games and sports? Perhaps we’ll once again find time to relax and enjoy a favorite activity, free from stressful competition and the need to get something done.

Clyde Barker pushing Wayne Martin in a wheelbarrow, Pettigrew, circa 1940. Wayne Martin Collection (S-99-32-567)

What is play? Merriam-Webster defines it as “the spontaneous activity of children.” The word comes from plega, an Anglo-Saxon word meaning sport or game. While children’s activities are often described as play, similar activities by adults are termed leisure. Recreation is seen as more purposeful and organized, like playing a sport.

The notion and importance of play has changed over the centuries. When Europeans first settled in the New World, they didn’t have time for play. The average child might have a couple of modest, homemade toys—a carved animal, a rag doll—but chores filled up most of the day. Entire families worked at farming, homemaking, and earning a living. This was mostly a matter of survival, but Puritan belief also held that idleness was wrong.

Things started to change in the mid 1800s with the Industrial Revolution. As cities grew and technology advanced, people left the farm to work in factories and at jobs in town. At the end of the long work week, employees were left with a bit of free time. But what to do with it? Progressive-era social reformers promoted leisure activities as a way for the working class to renew their mental and physical energy and connect with family.

Before the Industrial Revolution, children were treated as little adults, wearing similar fashions, working strenuous chores, and being exposed to the same unpleasant realities as grown-ups. As industrialization progressed and affected society, children came to be viewed as innocents needing protection, instruction, and nurturing. Childhood was recognized as a separate phase of life, and toys, fashion, and attitudes changed accordingly.

Girls clowning around, Bentonville. From left: Dorothy Love, unidentified, Hattie Finney (standing), and Ora Crawley, 1920s. Jo Hall Collection (S-96-2-64)

At the beginning of the 19th century, adults believed that children’s toys and games should both educate and teach morals. America’s move towards industrialization made toys more plentiful and affordable for the expanding middle class. More toys meant more marketing. Products were designed and sold on an annual cycle, with Christmas as the focal point. By the late 1800s, it was okay for toys to be fun.

The growth of the business world changed society as well, bringing ideas of teamwork and competition to activities such as sports. Leagues were formed, rules were refined, and the strenuous, manly life was promoted. The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was founded in England in 1844 to build character through a variety of means, including athletics. The notion of “muscular Christianity” furthered this idea by equating physical fitness with good morals and a strong nation.

Attitudes towards play changed even further in the 20th century. After World War I adults started participating in their children’s play. Youth culture came into force in the 1950s as television shows and products were marketed to children. By the 1980s scholars started wondering what toys say about us. Do beautiful, shapely dolls make us feel inadequate? Do toy guns and war play decrease our sensitivity to violence?

In many ways, today’s play seems different from earlier generations. Safety concerns keep children nestled safely at home or at sanctioned events, rather than roaming neighborhoods on their own. Activities are highly structured. There are play dates for youngsters, specialty camps for all sorts of pastimes, and numerous after-school activities. Technology and an emphasis on early education have brought computer games that teach toddlers their ABCs.

Unidentified girl with dolls, Northwest Arkansas, circa 1910. J. D. Johnson Collection (S-86-122-12)

More and more, children and adults are scheduling play, turning it into a job rather than free-spirited fun. Even dogs have their own play parks and doggie day-care activities. A 2007 study found that one in three American workers don’t take all of their allotted vacation days. And when they do travel, many engage in goal-oriented activities while juggling work-related emails.

So what does the future of play hold? Will we overschedule ourselves, making play a chore rather than a pleasure? Will businesses marketing must-have gear and lifestyles make play too expensive? Will we be harmed by violent, addictive, or dangerous games and sports? Perhaps we’ll once again find time to relax and enjoy a favorite activity, free from stressful competition and the need to get something done.

Toys

Ada Lee Smith with her Christmas presents, Fayetteville, December 25, 1931. Carl Smith, photographer. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-98-85-192)

Prior to the Industrial Revolution of the mid 1800s, most children had just a toy or two. But with the advent of mechanization, the growth of the middle class, the emerging concept of leisure time, and the mass-marketing of toys at Christmas time, playthings took on greater importance and children had more of them. Toys became even more plentiful following World War II as consumerism grew and the baby boom emphasized youth culture. Today’s parents may stand in line for days—and occasionally get into brawls—so that their child can find the latest toy under the tree on Christmas morning.

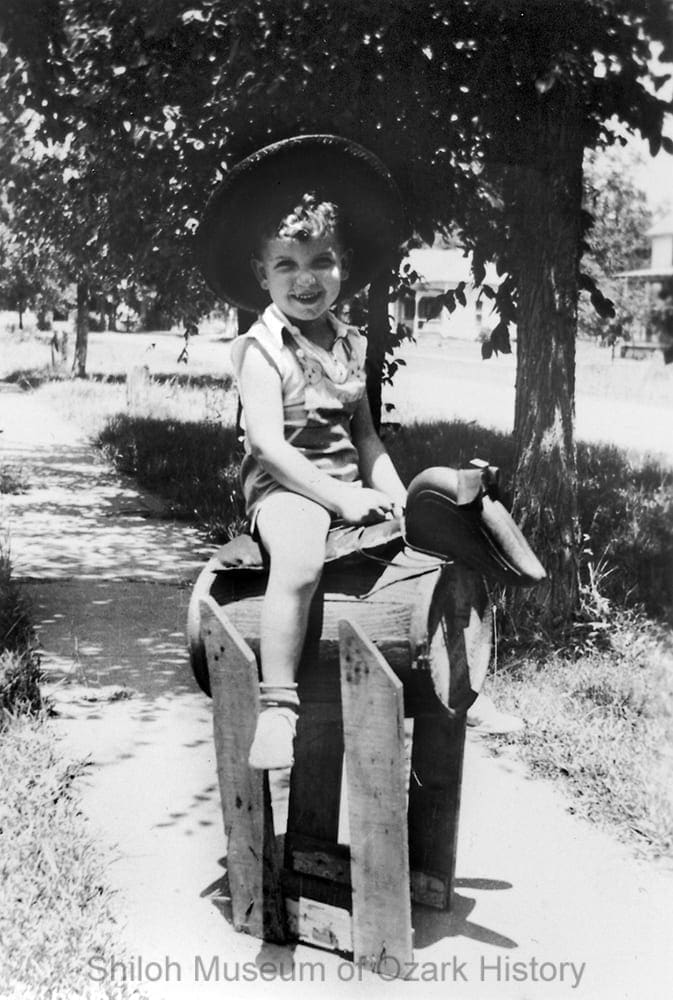

Railey Steele on a homemade barrel pony, Gravette, July 4, 1938. Sally Kirby Hartman Collection (S-95-43-151)

Toys can be simple or complex, store-bought or homemade. Long ago in the Ozarks, girls played with dolls made from fabric scraps, corn husks, or empty spools of thread. Boys had stick horses and slingshots made from tree branches.

The coming of the railroad to Northwest Arkansas in 1881 allowed stores to carry a large variety of manufactured toys, some of which were imported from Germany. National mail-order businesses like Sears, Roebuck and Co., which offered its first catalog in 1888, made toys even easier for children to dream of, and more affordable for parents to purchase.

Unidentified boy in a pedal car, Fayetteville, circa 1923. Carl Smith, photographer. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-98-85-1808)

Unidentified girl with her mammy doll, probably Northwest Arkansas, circa 1900. Ron Hoskins Collection (S-99-2-784)

Toys often reflect society’s values and cultural attitudes, for good or for bad. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, African Americans were frequently depicted by toy manufacturers in child-like, comical, and certainly derogatory ways.

Minority and immigrant groups were often portrayed with exaggerated physical features or character traits. Scholars believe that such ethnic stereotypes were a way for the dominant white society to portray itself as superior, especially in the face of increasing non-Protestant immigration and rapid social change. Massive immigration was brought to an end in 1924 with the passage of restrictive laws. Toys gradually became less stereotypical; instead, assimilation and tolerance were emphasized, although there is still far to go.

Bess, Blanche, and Bernice Hanks with their baby dolls, probably Northwest Arkansas, circa 1900. Marion Mason, photographer. Phillip Steele Collection (S-78-34-3B)

For centuries, toys were designed to teach adult roles and skills to children and instill moral values. For instance, by pretending to dress and feed their dolls, girls were thought to learn how to be good mothers. Boys picked up building skills while playing with their construction sets. Learning through play was even more important during the latter half of the 1800s due to the growth of the middle class. The luxury of leisure time meant that children had less practical knowledge of life skills such as caring for siblings or helping on the farm or in the family trade.

Sports

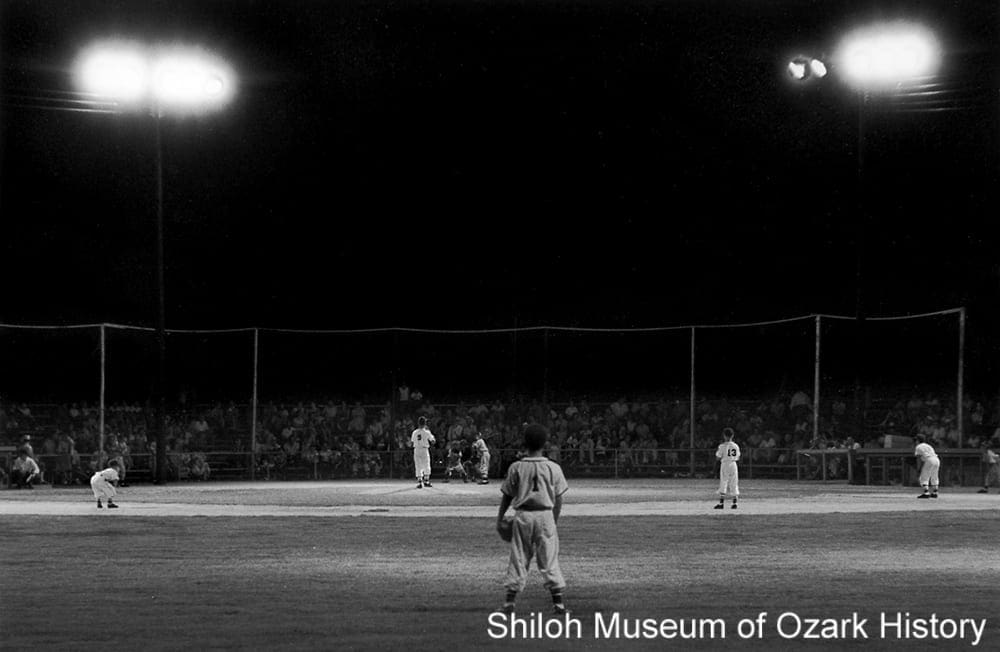

Little League game, Springdale, July 1956. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-463)

Ball games have been around for a long time, but baseball stemmed from a game played in New York in the 1840s. The growth of sports and the desire to organize into teams and leagues began after the Civil War, as people felt the urge to create their own communities within busy, isolating cities. Leagues for adults soon formed after the birth of baseball in the 1840s, but children were often left to play ball in the street. In the 1920s teenage leagues began, but boys had to wait until 1938 when Carl Stotz organized ball games for youngsters in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He hoped Little League would create good citizens by teaching fair play, teamwork, and sportsmanship.

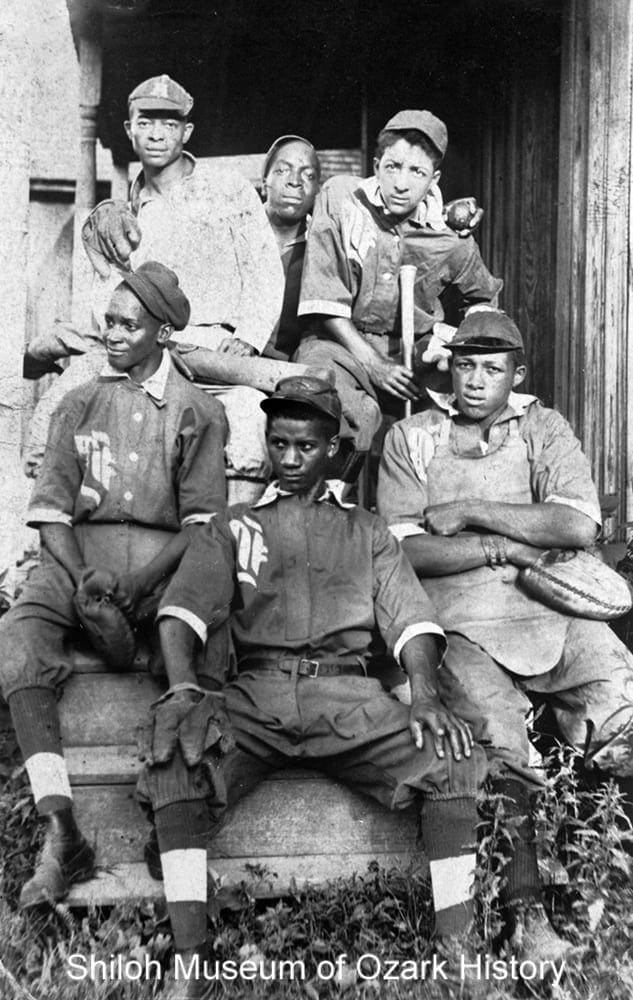

Bentonville baseball team, circa 1912. The team was part of a regional African-American league ranging from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Joplin, Missouri. Back, from left: Thad Wayne, Marion “Sonny” Finney, and Lloyd Trout. Front, from left: Yates Claypool, Virge Black, and John Barker. Elizabeth Robertson Collection (S-95-7-42)

At the turn of the 20th century, team sports were considered a good way for immigrants to assimilate into mainstream culture. Prevailing social attitudes kept African Americans segregated, forcing them to create their own teams and leagues in order to play competitive baseball. Segregation in American sports started breaking down when Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color line in 1947.

Berryville girls’ basketball team versus Eureka Springs, Carroll County, 1913. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-236-27)

In the latter half of the 19th century, the YMCA, President Theodore Roosevelt, and others promoted the notion of “muscular Christianity.” A commitment to manliness and health was important to overcome what was considered to be an increasingly sedentary, urbanized, and feminized lifestyle. Strenuous and aggressive sports were emphasized.

One way to continue exercising during the winter was by playing basketball, which was invented for this reason in 1891 by YMCA instructor James A. Naismith. Using a soccer ball and peach baskets for nets, the game quickly spread. Soon schools began fielding teams for boys and girls, making basketball the first strenuous, competitive, team sport which was acceptable for women to play.

The ancient game of golf first became popular in America among the upper class in the late 1800s, when advances like the rubber-centered ball made the game livelier. As was often the case, the middle class followed the lead of the wealthy, with cities building public golf courses. By the 1920s golf was seen as an informal way for professional men to advance their business interests.

Northwest Arkansas had several golf courses by the 1920s, including ones at Monte Ne and Bella Vista. As the century progressed, developers recognized the power of sport. When the old summer resort of Bella Vista was transformed into a vacation and retirement destination in 1960, golf was the main attraction. Then as now, folks could indulge their love of the game by building homes overlooking the golf course.

Recreation

Mary Parker and her bicycle, Rogers, 1890s. Mrs. Beaton, photographer. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-87-258-53)

With the introduction of a comfortable, easy-to-handle bicycle in the late 1800s, America went crazy for wheels. In 1890 150,000 people had a bike; by 1894 that number had jumped to four million.

Cycling was considered a respectable activity for women because it wasn’t strenuous or competitive. Young women probably enjoyed cycling even more than their parents suspected because it brought them a newfound sense of freedom. Not only could girls travel from home on their own, but by the mid-1890s bloomers and divided skirts, garments which were once frowned upon, were a necessary fashion for female cyclists.

The bicycle’s popularity lost ground when the automobile came on the scene in the United States. By the early 1900s, bikes were considered children’s toys.

Soap box derby, Fayetteville, July 1940. Northwest Arkansas Times photographer. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2525C)

At the turn of the 20th century, social reformers promoted the building of playgrounds and parks as prime places for recreation. The playground movement was a way to give children, especially those in cities, a structured and supervised place to learn play skills. At home, parents were encouraged to build sandboxes.

The jungle gym was born in Winnetka, Illinois, in 1920 when a mathematician’s son remembered a three-dimensional framework (used for teaching math concepts) on which he played as a child. Hearing the tale, the school’s headmaster thought such a structure would be perfect for children, so a mock-up was made out of iron pipe. The jungle gym was a hit!

Swings at Murphy Park, Springdale, Arkansas, August 1961. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-232)

Unidentified women with their snowman, Northwest Arkansas, 1930s. Washington County History Book Collection (S-90-32-202)

The great outdoors have always provided wonderful opportunities for people to play, whether by having a snowball fight, jumping into a pile of autumn leaves, or splashing around in a river.

As automobiles became more affordable in the early 20th century, families explored the countryside. Camping was a popular activity which allowed city dwellers a chance to reconnect with their pioneer roots by “roughing it.”

Unidentified girl at a hula hoop contest, Springdale, October 1958. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-23)

Every now and then a toy becomes a fad. This happened with bicycles in the 1890s and Cabbage Patch Kids® in the 1980s. During the late 1950s, the hula hoop captured the world’s attention.

Twirling a hoop around one’s waist wasn’t a new idea, but a small toy company called Wham-O® used colorful plastic to make their product fun and exciting. In 1958 the company heavily promoted the hula hoop on California playgrounds, sparking a fad that saw 100 million hoops sold in the first year.

Skateboarders on the University of Arkansas campus, Fayetteville, January 1990. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 52, P-23)

Skateboarding began in the 1950s when Californian surfers took to the streets on roller skate wheels attached to planks of wood. Skateboards allowed the rider to travel around town in a fun, but relatively sedate manner.

Public skate parks were introduced in the 1970s; in the 1980s kids built elaborate ramps at home to practice revolutionary tricks like the “ollie,” where both they and their board would pop into the air. Skate-boarders moved back to the street in the 1990s where they practiced tricks using whatever was at hand, such as curbs, railings, and benches.

Today skateboarding both influences and is influenced by music, language, fashion, and youth culture.

Imagination

Dressing up is appealing to young and old alike. Playing cowboys and Indians was a favorite pastime for many a youngster, who wasn’t concerned about stereotypes. Wearing costumes for Halloween and school plays was another way to have fun.

At home and in community halls, adults dressed up for theatricals, charades, and parties. “Mock weddings” were popular among single-gender groups. Members of an all-women’s literary society or a male fraternity would dress in wedding finery and portray both male and female roles.

Participants of a mock wedding at the Ozark Theater, Berryville, about 1936. Macy, photographer. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-136)

Hugh Jett and Tillman McKenzie playing house, Brentwood, December 1913. Mrs. William B. Poe Collection (S-91-84-37)

Children have long been able to create worlds with their imagination. Buy a young child a fancy toy, and often the box it came in holds more long-term appeal than the toy itself.

By the 1900s researchers recognized childhood as a distinct phase in life, one which required a new way of interacting with children. Many theories were developed on how best to raise and educate children and schools were created based on these ideas.

After World War I, the growing field of child psychology influenced the way children played. Certain kinds of toys and play behavior were suggested for particular ages. Play was appreciated for the enjoyment it gave to children and its ability to help them learn about themselves and what they were capable of. Parents were also encouraged to involve themselves in their youngster’s play, advice that continues to be given today. In recent years child psychologists have advocated imaginative play as a way for kids to relax and have time away from stressful, competitive, goal-oriented activities.

Games

Upper Wharton School students playing “London Bridge is Falling Down,” southeast of Huntsville, circa 1943. Vernon Williams Collection (S-96-1-161)

Many games that children play today have old roots. “London Bridge” has been around since the Middle Ages while “Blind Man’s Bluff” (a corruption of “buff,” a small push) dates back to Tudor times in the 14th and 15th centuries. Hopscotch began in Britain centuries ago as a training exercise for Roman soldiers.

The stories behind some games have been embroidered through the years. “Ring Around the Rosie” is an old rhyme that took on new meaning in the 1960s, when a researcher decided that its verses referred to the Bubonic Plague of the mid 1300s. Trouble is, there isn’t any evidence of the rhyme existing before the 1880s.

Northwest Arkansas Girl Scouts play tinikling, a game based on a folk dance from the Philippines, Bull Shoals State Park, Mountain Home, 1966. NOARK Girl Scout Council Collection (S-97-2-769)

A ball-toss game at the Tontitown picnic, circa 1910. Gloria Mae Maestri Sallis Collection (S-2006-150-11)

Informal, community-based fun has a long tradition in the Ozarks. Churches held dinners-on-the-ground (picnics), singing schools taught people to sing using shape notes (a simple form of musical notation), and play parties were a chance for youngsters to square dance without music, so as not to offend church leaders. In all of these activities, folks had a chance to get together as a group to strengthen community and social bonds and meet eligible partners.

The first picnic in the Italian community of Tontitown was in 1898. It was an event where the new settlers could socialize, have fun, and give thanks for their blessings. The tradition continues today. The Tontitown Grape Festival draws thousands of folks who enjoy a big meal of pasta and fried chicken, amusement rides, bingo, performances, and the Queen Concordia pageant.

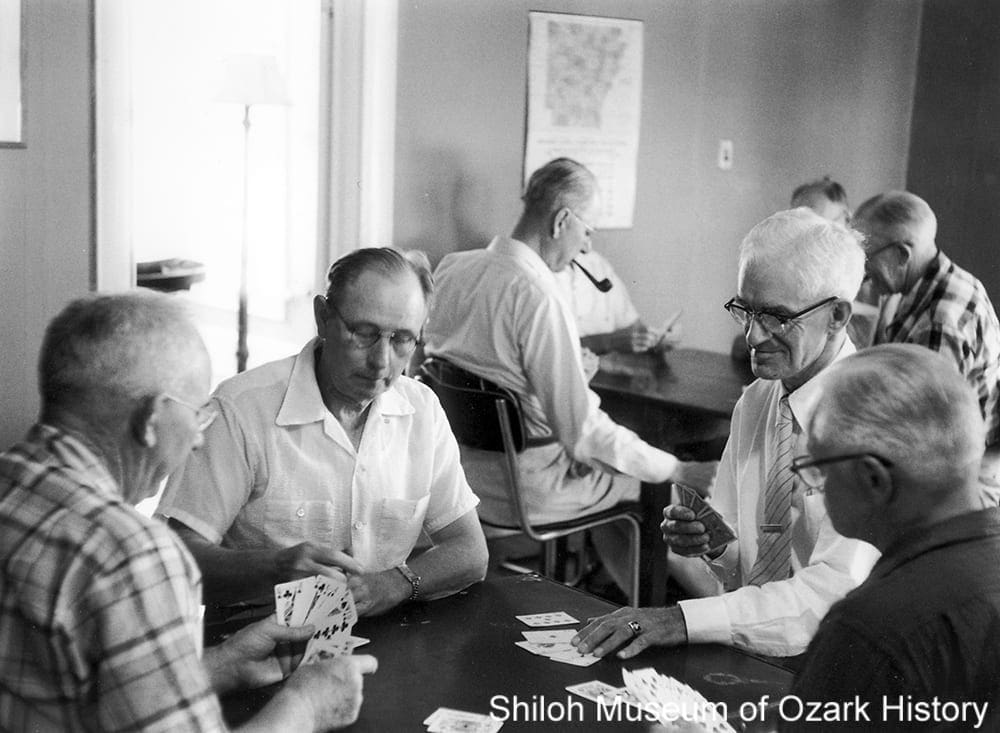

Men’s Recreation Club, Rogers, September 1956. From left: Lloyd Thomas, Bob Keegin, C. F. Shawley (with pipe), and Mr. Detloff. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-406)

For most of the 19th century, adults believed that games should be moral and educational. By the late 1800s, this attitude shifted and games were often played purely for fun. Although some religious denominations disapproved of card playing, families were encouraged to play card and board games at home in the belief that the family that played together would stay together.

The first reference to playing cards in western culture dates back to 1377, but it is believed that cards go back even earlier, originating in Asia. Card games have gone in and out of fashion over the years. Contract bridge was popular in the 1920s and 1930s and poker is now a televised sport.

Pinball players and videogamers at Hog Heaven, Springdale, December 30, 1982. Springdale News Collection (SMN 12-30-1982)

Changing technology has always had an effect on toys and games. Pinball began in the mid 1800s as bagatelle, in which a small stick was used to shoot a ball through raised pins into holes. Pinball’s popularity grew as the game became coin-operated and challenging flippers and plungers were added.

About the time that pinball was reaching its peak, a new game was on the horizon. Scientists used giant mainframe computers to develop games in the 1950s. Ralph Baer went one step further and demonstrated the first playable video games in 1966. Six years later “Pong,” a video tennis game, was in arcades and the “Odyssey” gaming system allowed folks to play such games as basketball and ping-pong at home.

Today video games are usually played at home or on handheld devices. Online gaming offers elaborate—and some would say addictive—multiplayer competitions. Some gamers get ahead by buying “virtual” goods with real money!

Credits

“History of Little League.” littleleague.org (accessed 6/2020)

“Pong-Story: The Site of the First Video Game.” pongstory.com

“2007 International Vacation Deprivation™ Survey Results.” Expedia.com.

Bellis, Mary. “The History of Pinball.” thoughtco.com (accessed 6/2020)

Braden, Donna R. Leisure and Entertainment in America. Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, 1988.

Cape Cod Toy Library. “Why Play Matters.” (accessed 6/2020)

Cave, Steve. “A Brief History of Skateboarding.” liveabout.com

Duran, Shelia. “’J’ is for Jungle Gym.” Winnetka (Illinois) Historical Society.

“History of Playing Cards.” The International Playing-Card Society.

Jackson, Kathy Merlock. “From Control to Adaptation: America’s Toy Story.” The Journal of American & Comparative Cultures; Vol. 24, No. 1/2, 4-1-2001

Marchavitch, Aaron. “A Definition of Play, Leisure, and Recreation.” Marchavitch.com (accessed 6/2020)

Nelson, Pamela B. “Toys as History: Ethnic Images and Cultural Change.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, Big Rapids, MI

Putney, Clifford. “Muscular Christanity.” The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education.

“Ring Around the Rosie.” snopes.com

Scott, Alec. “The Iconic Hula Hoop Keeps Rolling.” Smithsonian, July 2018.