Scenes of Newton County

Online Exhibit19th-Century Settlement

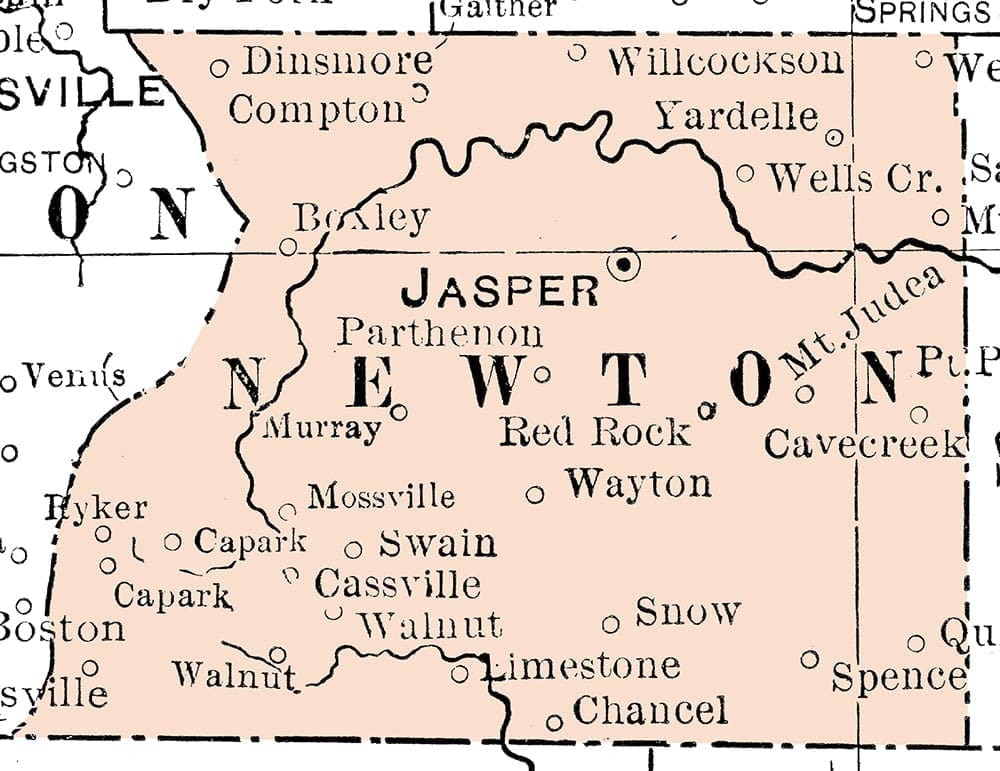

Native Americans once lived in, farmed, and hunted throughout what’s now Newton County. In Boxley Valley, archeologists have found prehistoric home and work sites dating back almost 7,000 years. An 1817 treaty with the U.S. government brought Cherokee settlers to Northwest Arkansas and present-day Newton County. Most of them moved to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in 1828, the result of another treaty with the government. Arkansas became a state in 1836. When Newton County was carved out of Carroll County in 1842, it was named for Thomas Willoughby Newton, then U.S. Marshal for Arkansas. One year later Jasper became the county seat. The first whites entering the area prior to statehood were hunters, trappers, and a few eager homesteaders. Some had Cherokee spouses and came with the first migration of Cherokee. They stayed in the area when the tribe was forced further west. Settlers used the forest to build their homes and selected rich bottomland to grow their crops. By 1850 there were 288 families in the county, numbering 1,711 people. Most were small-time farmers, without economic reason for holding enslaved workers. At the beginning of the Civil War there were about 25 African-Americans in the county, just a fraction of the overall population. Like much of Northwest Arkansas, loyalties were divided within communities and families—some sympathized with the Union while others were for the Confederacy. The county suffered its share of privation from bushwhackers, guerrilla bands, and skirmishes. Its valuable chemical and mineral resources were used for making gunpowder and bullets. After the war, the economy grew due to increased zinc and lead mining in the northern half of the county. Mines with colorful names like “Belle of Wichita” popped up everywhere, leading to boomtowns that flourished for a time. The rough terrain and remote location caused early railway planners to bypass the county entirely, making it the only county in Arkansas never to have a railroad.

20th-Century Growth

Logging truck, Newton County, 1970s-1980s. Carl P. Hitt, photographer. Shiloh Museum Collection (S-2016-24-32)

By 1900 the population had swelled to 12,538, due in part to land speculators and new, out-of-state homesteaders. Timber harvesting joined mining as a major economic force. Large lumber companies and many local individuals bought thousands of acres of timber land. Numerous sawmills and logging camps were set up to harvest and process logs into railroad ties, mine props, barrel staves, pencils, dimensional lumber, equipment handles, furniture, and the like. It wasn’t long before the county’s extensive virgin forests were cut-over.

At the turn of the 20th century, cotton was a primary source of income for area farmers, but boll weevils decimated this cash crop. Other important agricultural products included livestock, wheat, corn, oats, and fruit. But without reliable and inexpensive transportation, these industries failed to thrive as long-term sources of revenue.

Newton County experienced a brief industry boom during World War I, fueled by the need for metals in the manufacture of cartridge and shell casings. Land rich in zinc and lead fostered the establishment of mines in Ponca, Pruitt, and Bald Hill. But a drop in prices and the inability to easily export these resources after war’s end lead to their demise.

The population of Newton County dropped steadily from 1900 to 1960, with an all time low of around 5,700 residents. It began a slow recovery beginning in the 1960s with the influx of newcomers arriving with the back-to-the-land movement. This growth continued in the 1980s.

21st-Century Future

The county’s rugged geography has had a significant impact on its history and people. The progressive changes brought about in the past 100 years for most of the U.S. were late to arrive. Rural electrification was introduced as late as 1937; the first high-power lines weren’t installed until 1949. The first modern roads did not come until the 1950s, preventing sustained growth in manufacturing and industry.

However, it is the very nature of Newton County’s geographic seclusion which is largely responsible for the preservation of the natural beauty which attracts visitors from all over the world. Today tourism is the county’s major industry. Attractions include dude ranches and the Buffalo River which draws over 800,000 visitors each year. Ecotourism activities like hiking, camping, caving, outdoor cookouts, rock-climbing, and zip-lining in the Ozark National Forest and Lost Valley are popular. Many retirees come to the county to enjoy an easy-going lifestyle and beautiful scenery.

Timber continues to play an important economic role. While production has dramatically decreased over the decades, small-scale sawmills and other wood-product companies are still found amongst the hillsides.

The 2010 census reflects the relative isolation of Newton County. With 8,330 residents it is the 7th least-populated county in the state. Its population density is just 10 people per square mile. The largest city is the county seat of Jasper, with 466 people. Countywide, the median income is about $17,000 per person. More than 8,000 people self-identify as white, 9 as African-American, 90 as Native American, 25 as Asian, and 141 as having Hispanic origin.

Newton County’s rural past is still evident in the small, isolated communities tucked amongst its hillsides and valleys. This way of life is recognized and treasured in many ways, from the designation of the Buffalo as the country’s first National River in 1972 to the creation of the Big Buffalo Valley Historic District at Boxley in 1987. Fayetteville author Donald Harington immortalized the long-gone community of Murray via his mythical and magical “Stay More” novels. In them he blended the speech and manners of rural Newton County with plenty of tall-tales involving six generations of the Ingledew clan.

Newton County Close-Ups

Newton County Courthouse

“Most everyone became panic stricken, rushing down the main aisle for the door, screaming and shouting. . . . All was in wild confusion and the noise was so loud that it was heard a mile or more away.”

J. Town Greenhaw

(Jasper, AR) Informer, February 28, 1948

There have been several courthouses in Newton County over the years. The first was a log structure, burned during the Civil War. After the war, court was held in several places, including a doctor’s office, a school building, and a saloon. Around 1873 Robbie Hobbs was charged with building a courthouse that would “last forever.” He built it out of cobblestone and coated the walls with mortar, polishing them until they were smooth and hard. Supposedly, a woman picked at the finish one day and made a hole. Some townsfolk, unsatisfied with the quality of the builder’s work, are said to have killed Hobbs.

A Christmas Eve party in the mid 1880s was held in the courtroom, even though a few cracks had begun to appear in the building’s walls. As the people awaited their gifts, someone shouted, “The courthouse is falling!” Panic struck. Some ran into the wood stove, knocking down the stove pipe. Many made a dash for the door while others leaped from the windows. Out on the lawn, women screamed for their children as doctors examined the wounded. Eventually the crowd quieted enough to receive their gifts. Apparently the building was strong enough to last another 15 or so years.

In 1902 land was purchased on the town square to build a new, two-story, limestone-veneer structure. In 1938 the courthouse burned to the ground, possibly as a result of arson. Many records were destroyed. A new courthouse, built by the Works Progress Administration, was begun in 1939 and completed three years later. Billed as fireproof, the Art Deco-style building has a concrete foundation and is made of stone quarried from the Little Buffalo River. It cost $42,000. The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

Jasper’s courthouse square has been the scene of many celebrations including the Newton County Fair and the dedication of the paving of Highway 7.

Civil War

Susie Villines with a kettle from the saltpeter works at Bat Cave, Boxley Valley, about 1960. It was used as a wash kettle for many years and first came into the family from Mrs. Villines’ grandfather, Abraham Clark. Courtesy Kenneth L. Smith, photographer.

“The enemy, surprised, barely attempted to form and scattered. …They fled in dismay, a race for life. In the charge and in pursuit for 8 miles, 30 were killed, a number wounded, and 8 taken prisoners. 23 heads of horses captured, and some 25 stand of arms, the larger portion of which was destroyed.”

Col. John E. Phelps

Second Arkansas [Union] Cavalry

April 23, 1864

The 1860 census listed 25 enslaved African-Americans for Newton County, less than one percent of the total population. Although there were no major Civil War battles in Newton County, skirmishes, bushwhackers, guerrilla bands, and divided families took their toll. Like the rest of Northwest Arkansas, some residents allied with the Union while others joined the Confederacy. The area’s many caves and isolated valleys hid men and supplied cover for military activities.

Malinda Newberry Logan lived on Kenner Creek near the Hopewell Community. During the war bushwhackers came to her home to steal food. They also ripped open the feather mattresses and rode their horses over them. The bedding was re-stuffed with dried leaves, causing a later band of marauding bushwhackers to remark, “Look here at this damn hog bed.” Malinda heard about a neighboring family who tried to hide their cured meat within a wall. The meat was discovered when grease stains penetrated the wood during warm weather.

The area’s natural resources were vital to regional war efforts. Lead deposits were mined to make bullets. Confederate forces established a saltpeter works at Bat Cave, near the headwaters of the Buffalo River. Saltpeter (potassium nitrate) is used to make gunpowder. It’s often found in the soil of caves heavy with bat and bird droppings. The soil was dug out and removed to wood vats. Water was filtered through and then boiled in large, iron kettles for hours, causing the formation of nitrate crystals. In January 1863 the First Iowa Cavalry destroyed the works, burning and smashing the equipment. The kettles were rescued by locals and put to use for washing clothes and scalding hogs, well into the 20th century. A few still sit in yards today.

The county’s biggest skirmishes occurred in April 1864. During the battle of Whiteley’s Mill (now Boxley), Confederate guerrilla bands, including one lead by Captain John Cecil, fought a scout patrol lead by Captain William Orr of the Second Arkansas (US) Cavalry. Cecil, a Confederate, was Newton County’s former sheriff; his brothers fought for the Union. After two hours of fighting, the Union side withdrew due to lack of ammunition.

A few days later Orr joined with Major Melton and others to search for Confederates whose mission was to disrupt Union supply trains passing through the county from southern Missouri. The Union forces tried to sneak up on the Confederates, who were camped in Limestone Valley, but were spotted by a scout. Still, the Confederate camp was in disarray when it was attacked on either side by Union soldiers, who pursued the fleeing Confederates for eight miles through wooded mountains.

Foodways

Workers possibly threshing oats, with a cornfield in the background, Western Grove, 1910s. Boone County Library/Edith Welburn Collection (S-87-127-88)

“The only obstacle in raising turkeys in those days was that the woods was full of wild turkey, and my turkeys would mix with them and refuse to return to their home.”

James Villines

History of Newton County, 1950

Early settlers generally raised enough food and livestock to meet their immediate needs. Most farms were small, given the steep and heavily forested hills. Farmers grew clover, sorghum, corn, peas, and beans in the river bottoms and along the mountain “benches,” narrow shelves of land. Larger farms existed in the northeast section of the county and along the river bottoms, where fields of barley, oats, rye, corn, alfalfa, and wheat grew well. Around the turn of the 20th century cotton was the principal crop, but boll weevils took their toll.

Families ground their corn into cornmeal at home or, more likely, took it to their local grist mill, such as the Whiteley Mill in Boxley Valley. Hogs were fattened up and slaughtered in the fall. The dead hog was scalded in a vat of hot water and hung up by its back legs. The hair was scraped off, the blood drained out, and the entrails removed. Then the carcass was butchered. The meat was salted down and hung in the smokehouse for curing. The fat was rendered into lard, the skin fried into cracklings, and the remaining bits turned into sausage and head cheese. “Hog-killing time” was often a time for neighbor to help neighbor. They’d share both work and meat. Children enjoyed playing with the “balloon” made from the hog’s bladder.

In the late 1800s, James “Beaver Jim” Villines grew corn in the rich bottomland of Boxley Valley. But first he had to clear the land of a thick growth of river cane. It was hard work because, after the cane had been dug out, it had to be burned. But the soil was rich and Villines could get 50 bushels of corn or more per acre. He raised turkeys, grew sweet potatoes, and sold seed and plants to his neighbors. Villines was a successful hunter, trapping otter, mink, and beaver. Beaver skins sold for $3 each while high-quality otter pelts went for $20.

Over in Low Gap, Isaac Whishon grew fruit trees and berries on a hillside bench. He was so good at it that he had excess fruit. He purchased an evaporator and began drying fresh apples and peaches. Sometimes he would spread cut fruit to dry on the roof of his home. His wife Cynthia turned the fruit into preserves and fruit butters.

Some farmers ran small-scale beef operations for the cash it would bring. In the early 1900s there were concerns about southern cattle being infected by ticks carrying Texas fever, a contagious and deadly disease. While local cattle might have some immunity, midwestern and northern cattle did not. It was feared that cattle shipped north for slaughter might bring the disease. In 1906 the federal government began a tick eradication program, asking farmers to dip their cattle biweekly in vats of pesticide. While some farmers welcomed the effort, many were against the program, angry about the government’s intervention. In Newton County, tick inspectors met resistance. One inspector noted, “Some trouble here at first, as many refused to dip cattle.” But in 1914 the county was considered free from Texas fever.

Religion

“This little church [at Walnut Grove, in the Boxley Valley] has been the scene of worship and weddings, revivals, and funerals for many years. . . . Near the church is a cemetery where our babies, our spouses, our parents, and our grandparents rest in peace.”

Orphea Duty (1969)

Old Folks Talking, 2006

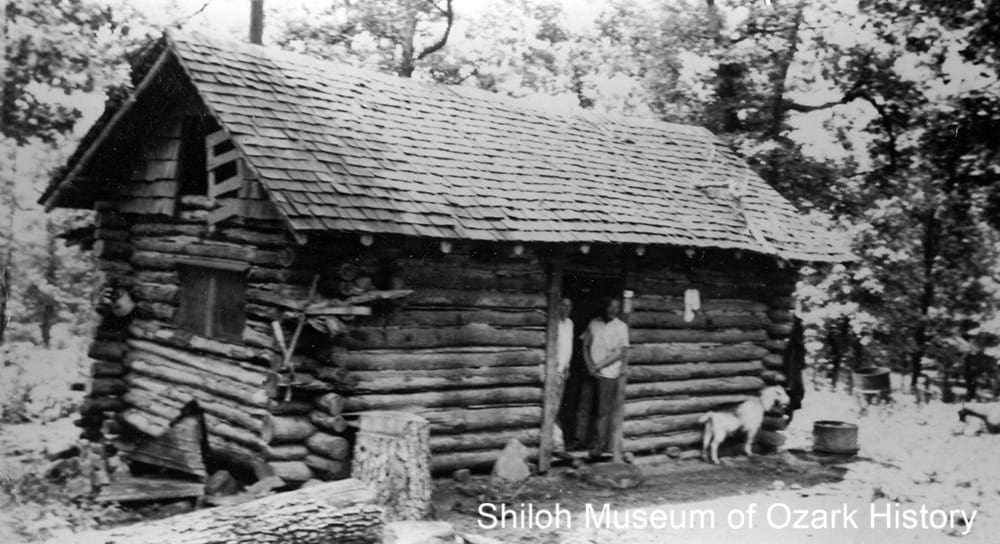

The first churches were small, log structures. As communities prospered, larger, wood-frame buildings were built. These buildings were often shared by churches, schools, and fraternal organizations. They were places where the community gathered for all kinds of events, from revivals to school pageants to fund-raising pie suppers.

Religious activities occurred outdoors as well. Baptisms were held in the Buffalo River and other county streams. In the summer and fall, brush arbor revivals were held under a rough wood structure roofed with brush and leaves. Participants often sat on wood benches to sing, testify, and listen to sermons. Dinners on the ground were social affairs held by the members of a congregation. Sheets and blankets laid on the ground in a long row held all kinds of wonderful food.

Circuit-riding preachers traveled by horseback from one country church to another, preaching to and praying with the locals. Families fed and housed the preachers whenever they passed through their community.

In Lurton, Uncle Dan Hefley tended to his flock at the Lurton Assembly for over 20 years, beginning in 1944. He could baptize up to 40 people a day. When she was young, Hefley’s daughter Lillie often traveled with him by foot or horseback to participate in revivals at Hasty, Low Gap, Jasper, Mt. Judea, and Gum Springs. Some revivals lasted over two weeks. Lillie remembered a few Sundays when her father couldn’t preach because the church’s altar, where he stood, would be filled with people seeking the Lord, wanting to be saved.

Timber

Jim Tate driving a log wagon, William Armer’s place, Osage Township, 1910s-1920s. Eva Taylor and Wally Waits Collection (S-85-51-6)

“The breaking of the log jam [on the Buffalo River] became a risk for the floaters. . . . As long as the logs are in a jammed stage, a person can run across them with ease, but when they begin to separate, stepping on them causes the logs to turn. This is what happened to my brother [Craft J. Lackey]. When he finally made it to the bank, he lost no time in locating the foreman to tell him that he had no further desire to float logs.”

Daniel Boone Lackey

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1960

Early settlers in Newton County found virgin forests full of ancient oak, ash, walnut, pine, and hickory. Red cedars lined the banks of the Buffalo River. One amazing cedar tree near Pruitt was about 42 inches in diameter at the ground and around 85 feet tall.

Besides using timber for building homes and barns, wood had commercial value. Local farmers could cut logs or barrel stave bolts for a much-needed infusion of cash. In the Low Gap area, Amos B. Lackey cut cedar trees during the winter in the 1880s. One year he was able to buy luxuries for his family including a metal washboard and clothes wringer for his wife, a set of harnesses for himself, and a “Hot Springs” diamond ring (quartz) for his daughter.

Logging was hard work and held many risks. Portable sawmills and stave mills were set up throughout the county, moving from section to section. Without a railroad line running through the county, transporting logs to market was difficult. Mule teams were used to snake logs out of the woods and haul log wagons over rough roads to neighboring counties and their railroad depots. Beginning in the early 1900s, tens of thousands of red cedar logs were floated down the Buffalo River to be turned into pencils.

The timber woods were soon depleted. After operating out of Boxley Valley for over two decades, the Malnar brothers of Austria left around 1940 once they could no longer find white oaks big enough to turn into barrel staves. By the 1950s most of the first- and second-growth trees were gone. Without reliable timber sales, the local economy faltered. Today many county farmers still use their timber woods to supplement their income, whether by cutting firewood or selling logs to manufacturers.

In 1989 several local environmental groups opposed a large-scale logging operation east of Jasper by Mountain Pine Timber. They were concerned about its impact on water quality, wildlife, and soil conservation. But some residents were in favor of the logging, both for the work the industry would bring and to protect property rights.

The southern half of Newton County is part of the much larger Ozark-St. Francis National Forests. When it was created in 1908, what was then the Ozark National Forest was, for a time, the nation’s only major hardwood timber land protected by the government. Purchasing cut-over land where virgin timber once stood, the U.S. Forest Service aimed to provide a renewable hardwood source for the area’s wood-based industries. Under today’s multiple-use management system, the forests’ 1.2 million acres are used for timber harvesting, recreational activities, grazing, and protection of wilderness and wildlife management areas. Counties receive 25% of revenues from use of resources. Much of these funds come from timber sales.

The Great Depression

Mrs. Garrett Jones and children at their home, Newton County, 1933-1935. Opal and Ernest Nicholson, photographers. Katie McCoy Collection (S-95-181-31)

“We heard a lot about the depression on the radio and in the newspapers, how it was so hard on everybody across the country. But we weren’t bothered by it that much. . . . Maybe out in the eastern part of the county people might have been on welfare, but here in Boxley we had our good farms, and we raised about everything that we needed.”

Orphea Duty (April 1, 1996)

Old Folks Talking, 2006

In the 1930s timber was playing out, jobs were becoming scarce, and a regional drought affected farming severely. In some ways, the Great Depression hurt city folks more than country folks. The latter were used to being self-sufficient, producing their own food and making or repairing much of what they needed.

Cash might be earned by selling animal skins, stave bolts (used in barrel making), or goldenseal roots and ginseng, medicinal plants which grew in the wild. ‘Seal was used as an antiseptic and to stop bleeding while ‘seng was prized in Asia for its believed ability to restore and prolong youth.

But for some, their farms were too poor or their luck too rotten to make things work. They left the county, seeking employment elsewhere. Over in Boxley Valley, Tom and Gracie Fults moved to Ohio while the children of Tim Villines, a former enslaved worker, relocated to Oklahoma.

Some county residents received aid from the federal government. Ernest and Opal Nicholson ran a relief program in Newton County. They worked with several caseworkers to administer to the needs of their clients, many of whom were widows or people with disabilities who had no way to earn an income. Help came in many forms. Some clients were issued beef or canned goods, provided with reading material, supplied with clothing and household necessities, or given funds to purchase windows and screening materials.

A few clients were found jobs at sawmills or driving trucks. Clients received encouragement and advice from the case workers. One child was told “how nice she would look with her face washed nice and clean” while a woman was encouraged to plant flowers “because of the social value to [the] home.” Caseworkers were said to have “accomplished some desirable results by mentioning the nice things which the clients had done and suggesting other improvements.”

Through its many programs, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) gave employment to a variety of folks. The Federal Writer’s Project hired people to create travel guides and interview settlers and former slaves. In what was then the Ozark National Forest, the Civilian Conservation Corps created miles of trails. The courthouse at Jasper was built by WPA work crews, as was the gymnasium at the Newton County Academy and the Little Buffalo River Bridge, both in Parthenon. In Boxley the crews built concrete outhouses.

Rural Electrification

Rural Electrification Administration meeting, Newton County courthouse, Jasper, late 1930s. Newton County Times Collection (S-88-234-89)

“My dad [C. V. Burdine] went from house to house almost day and night for several weeks signing up people as members of Carroll Electric Cooperative so that electricity could be brought into our area. . . . One of Dad’s favorite sales pitches and reasons for wanting electricity . . . [was] to have good lights in schools and churches. That reason just about won everyone—even if they weren’t too interested in getting electricity for their home.”

Kathryn Burdine Wheeler

Rural Arkansas, May 1984

In 1940 when the state population stood at 1.95 million, only 112,050 Arkansans had electricity, mostly in larger towns and cities. While there were several power-generating facilities, distribution was a problem. The federal Rural Electrification Act (REA) of 1936 was meant to improve that situation, along with improving the lives and incomes of farmers struggling with flood, drought, and the Great Depression.

Rural electrification was costly. Farms and homes were spread out, sometimes with just a few potential customers per mile. It often wasn’t profitable for privately owned power companies to take on rural customers. But with REA loans electric cooperatives could be formed, sharing the costs amongst their members. One such co-op is Carroll Electric Cooperative Corporation, incorporated November 1937.

In October 1938, 150 Carroll County customers were able to turn on electric lights in their homes for the first time. Seeing the success of the new venture, neighboring counties, including Newton County, petitioned the cooperative for similar service. County extension agents and volunteers went from home to home, explaining the work of the cooperative and signing up members for $5. Local residents were hired to clear brush and trees from right-of-ways, earning a whopping $2.40 a day during a time when the going daily rate for farm work was about 75 cents or $1.00. Soon utility poles and giant spools of wire were being brought in on big trucks.

Early co-op members were wired for one outlet per house with one drop light in each room. Over in Vendor, young Kathryn Burdine and her family waited anxiously for the electricity to be turned on, pulling on the light-bulb chain every now and then to check. When the electricity finally came one August night in 1940, she thought the folks at church seemed a little self conscious in the brightly lit building.

Electricity allowed Kathryn’s mother to use an electric iron for the first time while Kathryn and her siblings could listen to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio without fear of running down the battery. Later on, she and a sister saved money from their jobs and, with their brother’s sale of a pig, the three of them were able to buy a refrigerator for their parents. It was such a luxury for her dad to be able to have a thermos of ice water when he worked his farm fields.

In 1948 the REA began surveying the route for a proposed 33,000-volt high-power line to Jasper.

Highway 7

Jasper mayor A. B. Arbaugh introducing Governor Orval Faubus at the Newton County dedication of Highway 7, Jasper County courthouse, September 7, 1956. Newton County Times Collection (S-88-234-87)

“All this weekend there has been lots of activity around the Town Square when folks have been working like beavers, cleaning up, getting ready for our ‘Big Day.’ . . . Every day we’ve seen folks washing windows, cutting grass . . . and a whole crew, directed by Mayor A.B. Arbaugh were raking leaves on the Court House lawn and sweeping all gutters clean.”

Jessie Lu Abell

(Jasper, AR) Informer, September 1956

Early roads were often maintained by local governments. Able-bodied men armed with shovel, pick, and pry bar were expected to work on their community’s roads four days each year. Those who could afford it hired men to do the job for them. Many of these roads were poorly built, constructed under an elected township road overseer with little engineering or construction experience.

As the automobile gained prominence, road building took on greater importance. The Arkansas State Highway Commission was created in 1913 to address the need for a statewide system of roads. During the first half of the 20th century, Highway 7 was a rough, gravel road. But the need to improve it grew.

Road crews paved the road between Boone County and Jasper first. At the June 1951 dedication of this stretch of highway, onlookers enjoyed a parade and listened to the Harrison High School band. They also heard from speakers such as U.S. Representative J. W. Trimble, U.S. Senator J. W. Fulbright, and Governor Sid McMath and his aide, Orval Faubus. A noon dinner was served complete with “fried chicken, roast pork and roast beef, potato chips, bread, pickles, coffee and cake.” Festivities were paid for by local merchants. Both the Harrison and Russellville chambers of commerce sent car caravans. A similar celebration was held in September 1956 to celebrate the paving work from Jasper on south.

With its completion, Highway 7 became the first paved road to traverse the whole county. It linked Jasper to the larger cities of Harrison in the north and Russellville in the south, with all of their job opportunities, professional services, and shopping choices. The highway wasn’t a boon for all. Small towns like Lurton which once had a booming economy, due in part to the local wood-handle mill, suffered when it was bypassed by the highway.

The road linked Arkansas to Newton County, ushering in many tourism opportunities. Traveling south from Boone County, visitors would have had a chance to visit Dogpatch U.S.A., Paradise Hill with its craft and gift store, the county seat of Jasper, Diamond Cave, Arkansas’ “Grand Canyon,” Lost Valley with its six waterfalls, the Buffalo River and canoe outfitters at Ponca, and the Ozark National Forest. Highway 7 became the state’s first scenic byway in 1993.

Several landslides have damaged the road in recent years. In 2009 an area of highway just south of Jasper collapsed due to heavy rain. A few years later, repair work to fix the earlier damage caused a section of road to collapse again. In 2011 the state proposed changes to enlarge and realign the road and to replace the historic 1931 steel through-truss bridge over the Buffalo near Pruitt. A new bridge is expected to be built, but debate continues regarding the old bridge. While many want it preserved, neither the county nor the National Park Service can afford its maintenance.

Buffalo River

Canoeists at the take-out spot, Buffalo Point, Buffalo River, June 25, 1972. Mary Stockslager, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 6-25-1972)

“Everything you see here, everything except the tops of those bluffs, would have been submerged beneath a reservoir behind one of two dams the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had planned to build. …Wild rivers, I’m afraid, are a vanishing species.”

Neil Compton

National Geographic, March 1977

“Movin’ out o’ here would mean givin’ up all I’ve got, all I’ve ever had. I hope to stay just as long as the Lord and those Government folks allow.”

Eva “Granny” Barnes Henderson

National Geographic, March 1977

Flowing about 150 wiggly miles east from its headwaters near Boxley towards its confluence with the White River, the Buffalo River has been many things to many people. Native Americans and later settlers used the river for food, water, and transportation. Entrepreneurs harnessed the river’s energy to run mills and float raw materials like cotton, minerals, and red cedar logs (for pencils) to market in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As early as 1897 the U.S. Corps of Engineers looked at making the river navigable through a series of locks and dams, but the cost was too high. In 1936 a dam was proposed for power generation and flood control but never materialized because of the Great Depression and World War II. The Corps revised their plan in 1954, proposing two dams and the construction of Lone Rock Lake. While supported by many locals and members of the U.S. Congress, legislation to dam the river failed repeatedly.

In the late 1950s, Kenneth L. Smith, a University of Arkansas student, began a personal campaign extolling the beauty of the Buffalo through newspaper and magazine articles. His work helped popularize the notion that the river was worth saving in its natural state. U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright obtained an appropriation to fund a survey of the river by the National Park Service, which later declared that, as one of the last free-flowing rivers in the country, it should be preserved.

Dam proponents and opponents geared up for battle. Governmental agencies such as the Corps and Park Service opposed one another’s plans. Local organizations were formed, including the pro-dam Buffalo River Improvement Association and anti-dam Ozark Society, lead by Dr. Neil Compton of Bentonville. In Newton County some citizens wanted the dams for the progress and jobs they would bring, while many who lived along the river wanted neither dams nor a National River.

After many years of struggle, in 1972 the U.S. Congress officially designated the Buffalo a National River, the first in the nation. But opposition to a National Park continued. Many river-valley residents were upset with Park Service plans because it meant that they would be forced to sell their land to the federal government, leaving the homes and farms their ancestors had worked so hard to build.

In later years, Compton came to believe that pollution was the river’s greatest threat. In 2013 the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality awarded a permit to build a major hog farm near Mt. Judea. Concerns quickly grew about the potential for damage to the river from accidental runoff of hog waste. After years of protest and litigation, in 2019 the State of Arkansas agreed to a $6.2 million buyout of the company. The land is now protected under a conservation easement.

Business

“No son of mine will ever sit down, fold his hands, and live off the Government. . . . I can’t keep the government from adding taxes and telling me how to run the plant I’ve spent half a lifetime building, but I can teach my sons to get out and hustle for themselves. By golly, the small business is the backbone of America . . .”

I. C. Sutton

Arkansas Gazette, October 16, 1949

Like churches, country stores were the heart of many a community. People collected their mail there and purchased or bartered for goods they couldn’t produce at home. Eggs could be traded for such things as baking powder, sugar, and salt. Store owners also bought animal skins and medicinal plants, selling what they gathered to traveling purchasing agents.

Boxley was named after William Boxley, the merchant who delivered goods to the valley stores and who later operated his own store there. The town of Ponca owes its name to the Ponca City, Oklahoma, Mining Company, which mined lead and zinc ore in the area in the early 1900s. As mining increased in the county, so did blacksmith shops which built and repaired equipment.

In 1929 I. C. Sutton bought a rough turn-handle mill and moved it to Lurton, renaming it the Lurton Furniture Factory. To keep the factory running during the Great Depression, it switched to making barrels and then handles for things like hammers, railroad picks, and axes. World War II bought prosperity to the newly renamed I. C. Sutton Handle Factory, the only war-related business in the county. After the war the business expanded its production to baseball bats, telegraph spade handles, and pike poles used for logging. The business relocated to Harrison in the late 1950s to keep down shipping costs. The move turned Lurton into a ghost town.

The paving of Highway 7 in the 1950s brought some prosperity to the towns along its path. New businesses sprung up. But the highway took away business, too. Some traveled to larger towns in neighboring counties, such as Harrison and Russellville, to conduct their business and do their shopping.

In the 1940s politics was the frequent topic of discussion in Jasper’s two cafés. Pearl’s Café was home to the Democrats while Upton’s Café hosted the Republicans. Today Upton’s is now the Ozark Café, and politics are still discussed.

In 2010 the Jasper Commercial Historic District, including the courthouse, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The simple, rockwork structures were influenced by the availability of the area’s plentiful stone and the town’s relative isolation, free from outside architectural trends. Five of the buildings were built by Gould Jones, a local blacksmith and builder. He constructed a small reservoir in town in the early 1940s to provide water to a tomato-canning factory. The factory was closed by the Arkansas Department of Health when tomato juice was found in local wells.

Camp Orr

“We seek to create a camp where a boy will have opportunity for instruction and practice in woodcraft skills. We seek to develop physical fitness and resourcefulness to adapt himself to his surroundings and to live out of doors.”

L. M. R. Rogers

Scout Executive, Westark Area Council

Ozarks Mountaineer, September 1955

“Being on staff [in the mid 1960s] was kind of a dream for a teenage boy. We’d work for four or five hours, then spend the rest of the day in this wilderness playground.”

Jack Butt

Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, May 25, 2003

Camp Orr was developed in the early 1950s by the Westark Area Council of the Boy Scouts of America, based out of Fort Smith. Located a few miles northwest of Jasper, along the banks of the Buffalo River, the camp is named after Raymond F. Orr, a Fort Smith industrialist and former Council president who was instrumental in the camp’s development.

When it came time to find a camp site, Orr and a few other men are said to have paddled the Buffalo in search of the perfect spot. Orr purchased parcels of land from local landowners and then sold hundreds of acres to the Council for $15,000.

The first organized camp activities were held in the summer of 1955. Early structures included a trading post, a dining hall housed in a large Army tent, and a 34,000-gallon concrete water reservoir. Today the camp hosts a few thousand campers each summer, making it Newton County’s second largest “town” after Jasper. Troops come from Arkansas and across the country to gain skill in such things as knot tying, fire building, and woodworking.

The camp’s natural resources are plentiful—a river for canoeing, forests for camping and backpacking, rocks for climbing and rappelling, and flora and fauna for studying. The camp even has its own haunting legend, that of Smokey Joe, a former scoutmaster who is said to have lost his sanity after being hit in the head with a rock.

When the Buffalo National River Wilderness Area was established in 1972, the camp found itself within the area’s boundaries, the only Boy Scout camp in America in a national park. At first there was concern over whether or not the camp could remain. Negotiations went on for five years. In the end it was decided that as long as the camp followed National Park Service guidelines, like keeping the road into the property unpaved, it could stay. In 2003 the camp celebrated its 50th anniversary in true camp fashion, with food, fun, and stories around the campfire.

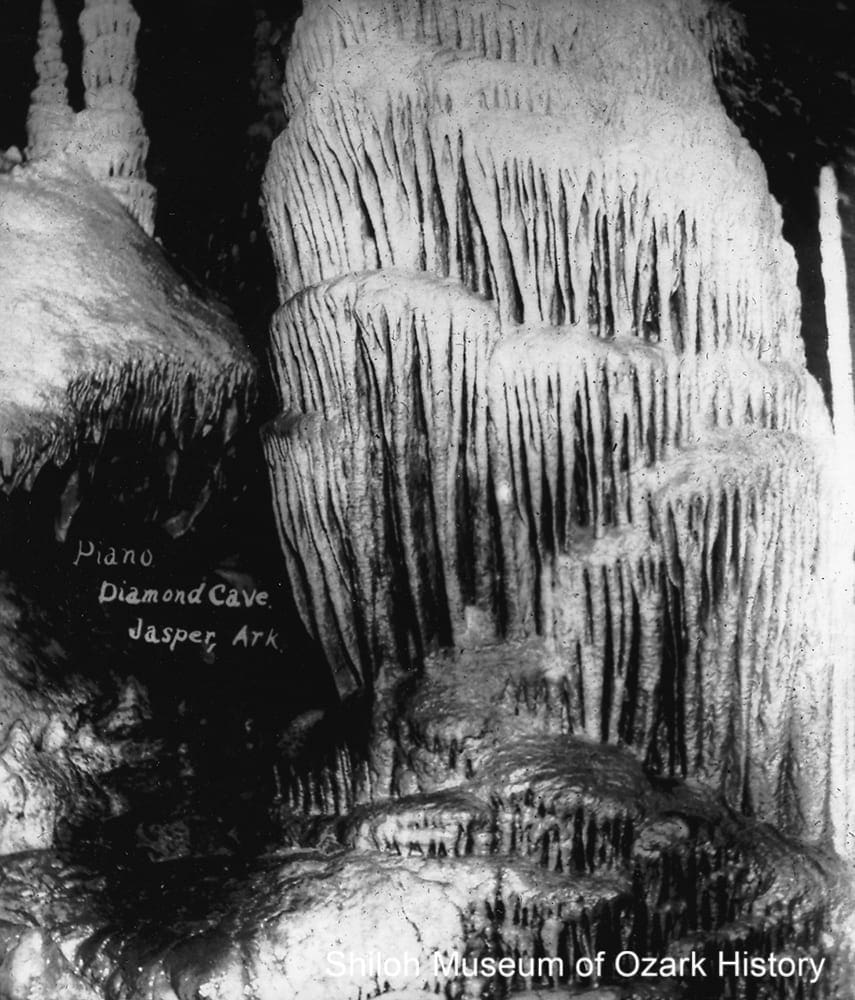

Diamond Cave

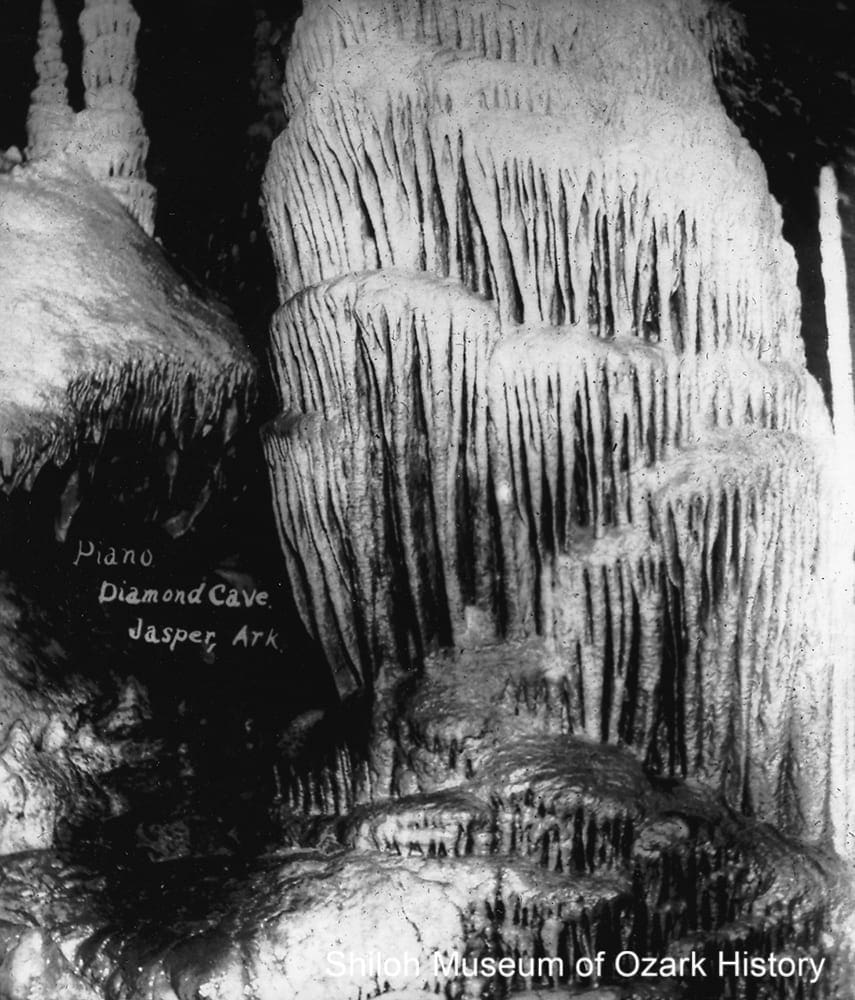

“Piano” formation, Diamond Cave, near Jasper, 1921-1925. Hidy Bouher Eby, Butch Bouher, and Lota Dee Bouher Lagan Collection (S-2001-2-12)

“There is a thrilling slide down Lover’s Leap to a point in the cave where visitors may behold the Pipe Organ . . . The calcite stems, or pipes of the organ, are so tense and delicate that the scale of music can be run by deftly tapping the rigid rock, and the cave is thus made to ring with melody.”

Playgrounds in Arkansas

1920s

Newton County is known for having a significant number of caves: Beauty Cave, Bat Cave, Civil War Cave, Beckham Creek Cave, and Hurricane River Cave. Perhaps the best known is Diamond Cave, located near Jasper. Likely named for the sparkling beauty seen as light glistens off of the cave’s dripping water and many-colored formations, the cavern is thought to have at least 20 miles of passageways.

The cave is said to have been discovered in 1834 by Sam and Andy Hudson, Tennessee migrants who homesteaded nearby. As the story goes, they were out hunting when their dogs disappeared into a hole in a hillside. Venturing into the cave with burning pine knots for torches, they found dogs and bears fighting. After killing the bears the men explored the cave for about three miles and saw its many wonders.

Early visitors explored with the aid of torches. They were guided by the son of one of the discoverers, who charged $2 for a group’s daylong tour. In 1922 W. J. “Jonah” Pruitt bought the cave and made improvements to it and the land. Three years later he sold the property to the Diamond Cave Corporation, maintaining a majority share of the stock. Walkways were created and protective handrails put in place. At first the cave’s electric light came from a gasoline-powered generator. Only one tour group could visit the cave at a time, as there wasn’t enough power to light multiple rooms simultaneously.

The trail through the cave was about two miles long. Fanciful names were given to various passages and formations—Crystal Lane, the Sugar Room, the Auditorium of Rome, the Statue of Liberty, and Fat Man’s Agony (a tight passageway). Baloney Pool owes it name to a tourist who didn’t believe the guide’s word that the water in a pool was deeper than it looked. Crying “Baloney!” he stepped into the pool only to realize the guide spoke the truth.

At various times the park had campgrounds and a bath house, rental cabins, a museum, and the Panther Inn, which sold refreshments and offered a hall for dances and parties. The rollerskating rink, built in 1939, was a popular place for local youngsters, who would often catch a ride to the rink on logging trucks from nearby communities like Deer, Ponca, and Low Gap. At its peak the cave had 10,000 visitors annually. On busy weekends the guides were given hamburgers as they left the cave with one tour group and immediately entered with another, eating on the go.

The cave closed to the public in 1988. In 1995 it was sold to the Mas Suerte Corporation of Texas. At the time the company indicated that it wanted to preserve and protect the cave and the surrounding property. Plans included restoration of native plants and trees and a wildlife refuge. The cave is closed at present.

Dogpatch

Statue of Jubilation T. Cornpone, Dogpatch U.S.A., Marble Falls, June 1968. The fictitious Cornpone was an incompetent Confederate general and founder of Dogpatch. Bob Edmiston, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 6-1968 #1)

“Dogpatch is really something else. People in the East think all the creativity and action is on the coasts, but the Midwest comes up with some fantastic ideas—like Dogpatch. It is a fine thing for Arkansas and it doesn’t hurt me either.”

Al Capp

Baxter (AR) Bulletin, May 16, 1968

Al Capp, creator of the “Li’l Abner” comic strip, was approached by a group of Boone County investors for permission to recreate his imaginary town of Dogpatch in the wilds of Arkansas. In 1966 they purchased a 160-acre trout farm near the town of Marble Falls, north of Jasper.

The first phase of Dogpatch cost over $1.3 million. Opened to the public in May 1968, the park featured buggy rides, a miniature railroad known as the “West Po’k Chop Speshul,” a trout farm, Ozark arts and crafts, a honey shop and apiary for bees, 1800s-era log cabins, and various hillbilly characters. Over 300,000 people visited the first year. Adults were charged $1.50, children 75 cents.

Soon there was a change in leadership; businessman Jess Odom gained controlling interest. New rides were added and a campsite developed. A few years later Odom broke ground on the Marble Falls resort, next to Dogpatch. The resort included a convention center, an indoor ice-skating rink, and—surprisingly—ski runs kept white with machine-made snow. Financial problems and mild winters led to the resort’s closure in 1977, the same year Capp retired his comic strip.

An economic feasibility study of the park in the late 1960s suggested that, by its tenth year of operation, the park would see over one million visitors a year. At best it attracted 200,000 annually. Competition with the nearby Silver Dollar City theme park in Branson, Missouri, didn’t help. Times were changing. In 1980 fiscal debt, changes in leadership, a decrease in tourism, and two money-losing summers forced the owners to file for bankruptcy.

Even as it struggled, the park stayed open. It added new attractions and featured country music stars like Reba McEntire. Owners came and went. In an effort to rebrand itself, in 1991 “Li’l Abner” and the other cartoon characters were replaced with a generic Ozarks theme. Dogpatch closed October 1993. A year later the Carr brothers of Boone County bought the property but didn’t do anything with it. Over the years vandals and souvenir hunters took their toll on the former park. The statue of Jubilation T. Cornpone was taken to Branson and may still be there on the bed of a trailer.

In 2005 a father and his teenage son were riding their four-wheelers on the property when the son ran into a steel cable strung across the road and was hit in the neck. There were questions about whether the property’s caretaker, another Carr brother, knew about trespassers and deliberately put up the cable as a deterrent. In 2011 the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld an earlier jury’s verdict to award money to the injured family. As the Carrs didn’t pay the judgment, the Dogpatch property was transferred to the family and their lawyer. Since then, the land has been in limbo. The current owner is anxious to sell.

Elk

Elk, Boxley Valley, January 24, 1993. Jill Smith, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 1-24-1993)

“They’re mean, wild and stout. . . . A lot of people here would never get a chance to see them if we hadn’t brought them in. I’m just tickled to death with the way they’re doing and with having them here.”

Robert Harrison

Arkansas Gazette, February 11, 1985

Elk once roamed North Arkansas, as evidenced by name of the old Elkhorn Tavern in Benton County, which displayed a pair of elk antlers on its roof. But overhunting in the late 1800s and loss of habitat as prairies were transformed into farmland first reduced, then wiped out, the once-large population.

A century later, hunters petitioned the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission to reestablish the elk. When Hilary Jones joined the Commission in 1980 and saw Oklahoma’s successful elk reintroduction, he figured it could work in Arkansas. The Buffalo National River valley near his home in Pruitt seemed ideal.

In 1981 local volunteers brought the first seven elk from Colorado, where the animal was plentiful. The elk were transported in cattle trailers lined with sheets of plywood in order to reduce stress and minimize injuries. More elk were relocated over the next four years. Soon calves were being born. Today the population stands around 450.

The elk are quite a draw. Tourists often line Highway 43 in Boxley Valley to watch for elk, especially in October during the animals’ mating season. They also visit the new Elk Education Center in Ponca. Each year thousands vie for one of a few dozen permits for two five-day hunting seasons.

But not everyone is happy. Some locals have complained about the growing herd and their impact on cattle-grazing land and the region’s plants. There are also concerns about the danger to roadside tourists. A few worry that Boxley Valley is becoming a kind of zoo.

In 2012 several water, wildlife, and conservation agencies and groups sought to halt the U.S. Forest Service’s expansion of elk habitat into Bearcat Hollow, just east of the Newton County line. They claimed that the clear cutting, road building, and herbicide use needed to thin and manage the forest would be excessive and would endanger lands protected by the Arkansas Wilderness Act of 1984.

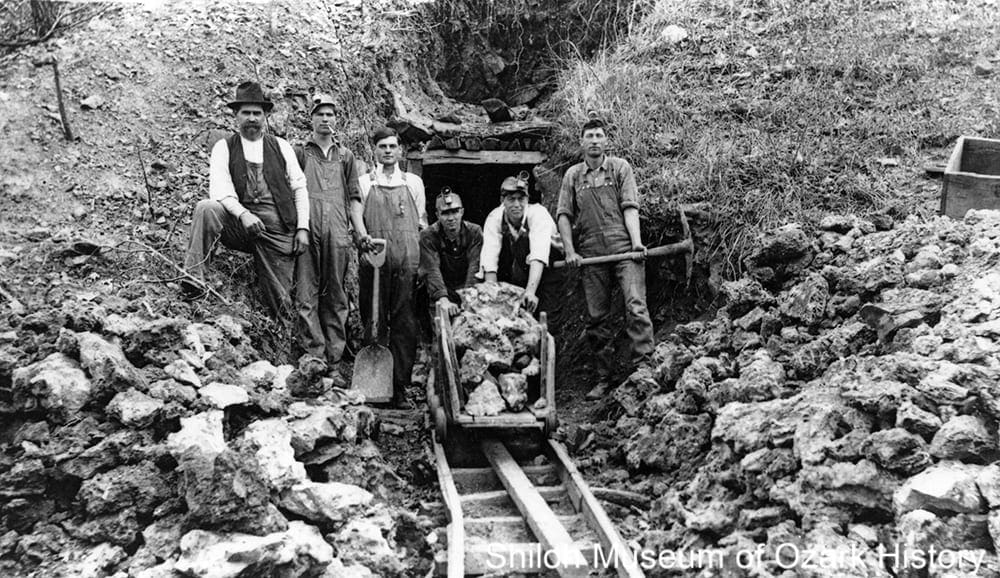

Mining

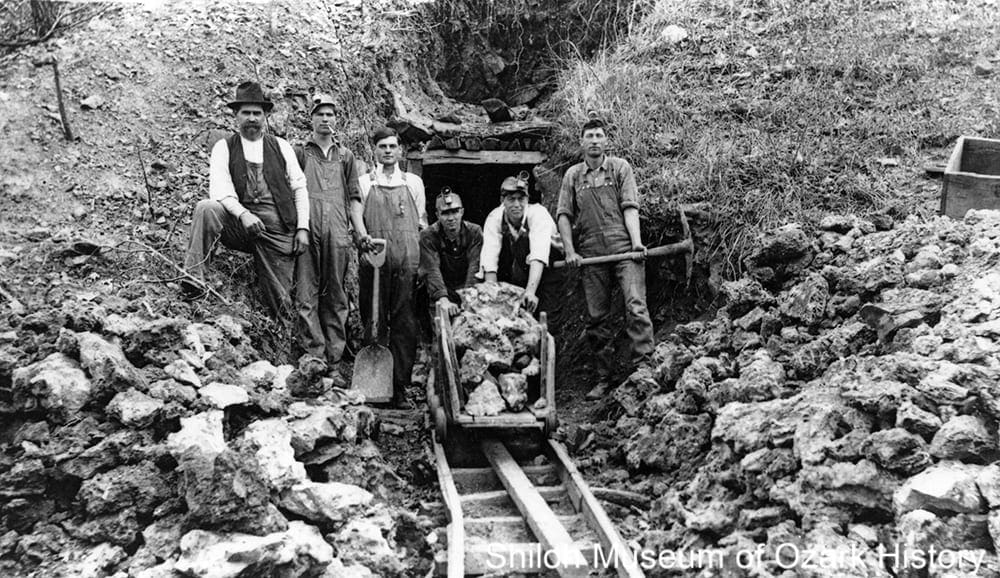

Kilgore Mine, Ponca, 1916. From left: Hope Strong, Lick Greenhaw, Lynn Jones, Hobert Criner, Frank Cheatham, unidentified, and Carol Greenhaw. Willie Bohannan Collection (S-83-82-56)

“Usually only about four men could work in a small tunnel [at the Panther Creek Mine]. One man was engaged in wheeling out the waste and collecting the ore worth saving. . . . From the ‘diggings’ a . . . track capable of supporting a small hand gondola car extended some 300 yards to the ore mill. At the end of the track the mined ore, a combination of dirt, rock, and ore, was dumped in the grill screen grates where it was broken . . . [and] fed to the crusher.”

Walter F. Lackey (1960)

Newton County Times, August 25, 1983

In the late 1850s, lead ore was mined and processed near the mouth of Cave Creek and at the headwaters of the Buffalo River near Ponca and Boxley. Over 18,000 pounds or more of ore was extracted, mainly for making lead bullets for rifles. The process was crude. Ore was dug out by hand from open cuts or shallow shafts. A crude smelter (furnace) made of stone was used to separate the metal from the rock. With the advent of the Civil War came the need for even more lead. The Cave Creek operation was worked by Confederate forces.

Lack of easy transportation limited the growth of mining. In the early days, raw ore and processed minerals were hauled by wagon over rugged terrain and then shipped down the Buffalo River. When railroads came to neighboring counties by the turn of the 20th century, materials were transported by wagon north to Harrison or west to St. Paul for shipment by rail.

By the end of the 19th century zinc mining had surpassed lead mining in importance. Zinc was used as a paint pigment, for battery electrodes, and to galvanize (coat) iron to protect it from corrosion. A 5,200-pound sample of nearly pure zinc from the Panther Creek Mine near Diamond Cave was said to have been sent for display to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, winning first honors in its class.

The need for zinc further increased by 1915, as World War I was underway in Europe. During this time the Panther Creek Mine produced about 3,000 tons of zinc concentrates. Prices began to decrease in 1917 due to a glut of minerals on the market, the high production costs of refining the ore, the area’s poor transportation options, and the loss of an able labor force as young men were recruited to fight. After the war, North Arkansas mines and their adjacent boomtowns were often abandoned.

Lead and zinc mining occurred off and on over the years, mostly small shovel-and-pick operations. In the 1940s miners were back at the old Confederate mine near Cave Creek, extracting large quantities of zinc and lead ore.

While lead and zinc were the primary materials mined or quarried in Newton County, there are also significant deposits of limestone, sand and gravel, and sandstone, as well as some coal and iron. Between 1895 and 1936 1,500 tons of coal were extracted from two mines in the northeastern corner of the county. Perhaps the first recorded instance of quarrying involved a 45-ton limestone block quarried in 1836 near Marble Falls for the Washington Monument in Washington D.C. A century later, a limestone quarry southeast of Jasper produced an estimated 50,000 tons of crushed rock during the construction of Highway 7.

Newton County Academy

Members of the Herculean Society, Newton County Academy, Parthenon, mid 1920s. Formed in 1920 as a literary society, the Herculeans gave programs and performances and participated in debates. Elmer Casey Collection (S-83-115-14)

“We admit we were freshmen, Much greener than the grass, But now we’re glad to say, We’re the sophomore class.”

Thomas Ryker

Newtonian, 1922

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, one-room schools dotted the countryside, serving to educate students in communities and towns. Schools operated for only a few months each year, when the children weren’t needed for farm work. But there wasn’t an avenue for higher learning until October 1920, when the Newton County Academy opened with 144 students. It was part of the Southern Baptist mountain mission school program, dedicated to bringing education and civilizing influences to rural areas. Describing Newton County as “the most destitute field in Arkansas,” the Baptists worked with community leaders to establish the school.

Donations in the form of cash, trees, and sawn lumber were used to build a two-story, native rock building. A girls’ dormitory was built to house out-of-town students as the Academy was, for a time, the only high school in the county. A rockwork gymnasium was built in 1936 as part of the Works Progress Administration program. The stage was paid for in part by area businesses in exchange for advertisements on the curtain.

The school offered coursework in music, mathematics, business, Latin, and the social sciences. Student societies focused on literature and religion. Tuition was staggered, depending on the grade the child attended. Seniors paid $4.50 per month, or $36 for the entire session.

Keeping the school going financially was a struggle. Money was still owed for the main building, so some of the school’s land was sold to help pay the debt. Many individuals and groups stepped up to help. Womens’ Missionary Unions in Arkansas and Texas helped fund tuition fees. The women of the Second Baptist Church in Little Rock assisted with dormitory furnishings and clothing. Baylor University in Texas, which directed the Baptist Mountain School program, provided equipment and maintenance.

The state took over the Academy in 1930, switching it to a public school. School consolidation in the 1940s and 1950s forced many of the local schools to close, moving students to larger, more centralized schools. At the Academy, students were transferred to the Jasper Public School district. The last high school class graduated in Parthenon in 1948; the last year of grade school was 1954.

Over the years the dormitory burned to the ground, the school building was dismantled for its rocks, and the gymnasium lost its roof. In the mid 1990s, Beulah Shelton began a campaign to save the gym. Through the donation of labor and money, including state capital improvement funds, the structure was rebuilt and rededicated October 2005. Today it’s used for community functions. The Academy was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.

Pastimes

James Braswell (far left) with members of the Jasper and Parthenon bands playing at a spring picnic, Diamond Cave, near Jasper, about 1910. Ardella Braswell Vaughan Collection (S-89-81-15)

“ . . . by this time Highway 7 had been upgraded considerably and people came from miles around to shake their shaves, get boozed up, and let their hair down.”

Henry Sutton

Mid-American Folklore, 2000

James T. Braswell was born in Carroll County, but lived in Jasper for about 25 years. A carpenter by trade, he also made furniture and musical instruments such as mandolins and violins. On Saturday afternoons in the summer, he led Jasper’s town band from the bandstand next to the courthouse. Braswell was also a songwriter, penning “In the Land of a Million Smiles” in 1925. The song was written on behalf of the Ozark Playgrounds Association, which used it for many years to boost its tourism efforts in the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks.

Community picnics were a frequent summer event in the early 1900s. Some picnics were quite elaborate with concession rights sold to the highest bidder. The day before the picnic, underbrush was cleared and booths set up for lemonade, ice cream, fruit, hot dogs, souvenirs, and the like. A horse- or mule-powered wooden “swing” gave round-and-round rides for a nickel. “Happy Jack” Moore of Swain was one of the best-known swing operators. He drew customers in with his singing, dancing, and snappy patter.

In Lurton, the picnic lasted for three days, drawing up to 1,000 people. Folks had a chance to catch a greased pig, dance to live music, or look for coins in a giant pile of sawdust. They could also pay for a ride in an airplane. In the 1930s, Lurton was the scene of some rowdy Saturday-night dances, courtesy of the local loggers and the workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps. As the nickelodeon played Western Swing music, couples courted and moonshine flowed.

Shooting matches were popular. In the early 1900s men and boys in the Low Gap community would lie on the ground with their muzzleloaders propped up on a log and take aim at paper targets tacked onto clapboards. Their rifles had names such as “Old Bangum,” “Yellow Jacket,” and “Old Countabore.” Contestants were given seven shots throughout the day, with the winners being declared after much scrutiny of the shot-up targets. Prior to the event, the contestants chipped in to purchase a steer for about $12. During the match, the animal was slaughtered. The winners received certain cuts of beef, depending on their ranking, with some selling their winnings to others.

In Low Gap, Isaac and Cynthia Wishon where known for their keen enjoyment of visiting with friends and neighbors. Cynthia was a good cook. The noon meal might include dried smoked beef and venison, sauerkraut, apple and pumpkin pies, fried chicken, potatoes, and turnip greens, all washed down with coffee, milk, and spicewood or sassafras tea. While the women gathered to quilt, knit, and share neighborhood news, the men played card games (“pitch” and “seven up”) and pitched horseshoes. Often folks tuned up their instruments to play songs such as “Buffalo Gals” and “Arkansas Traveler.”

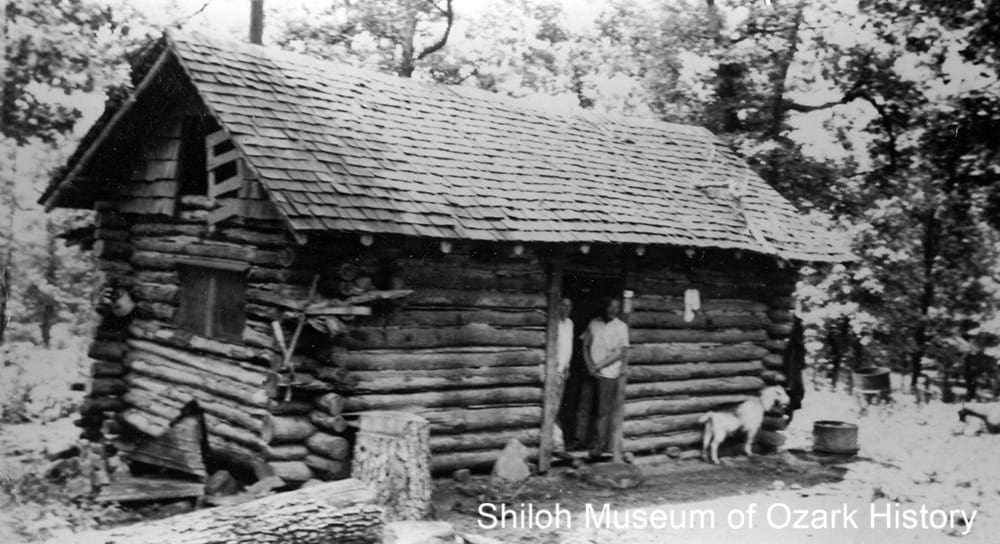

Ted Richmond and the Wilderness Library

Ted Richmond (right) at the Wilderness Library, Mount Sherman, 1940s-1950s. Flossie Smith Collection (S-98-88-525)

“I literally started with a Bible and a prayer. It has not been easy, but I have had the most remarkable answers to prayers. One summer when the drought burned up the gardens, I used nearly all my slender grocery money for the library, and lived on wild roots, wild onions, berries, and the like. But the books kept coming, and that was what I wanted.”

Ted Richmond

Christian Science Monitor, April 5, 1947

Born in Nebraska, James Theodore “Ted” Richmond lived in many places and had several jobs. But he grew tired of living in a fast-paced world, isolated from his neighbors. Eventually he found his way to Mount Sherman, a few miles northwest of Jasper.

With the help of his neighbors, in 1930 or 1931 Richmond cleared some land, built a small log cabin, and started a goat herd. His aim was to establish the Wilderness Library, a place where his neighbors could have access to the knowledge of the world. At first the only book he had to lend was the Bible. But he wrote to friends and publishers and soon books and magazines began arriving.

As word of the library spread, folks made the trek to pay a visit and borrow a book. For those who couldn’t make it, Richmond hauled 60-70 pounds worth of books in a canvas sack along rugged mountain roads and trails. He visited neighbors, sharing books, preaching and praying, and gathering news to bring to the next family on his route. Seeing a need, he began the “Wilderness White Christmas,” gathering and delivering small toys, clothing, medicine, shoes, and other necessities to his neighbors.

The Wilderness Library grew. Shelves of books were placed in schools and churches. A few branch libraries were established, including the Raney Branch further up the mountain from Richmond’s place. In the early 1950s it held about 1,500 volumes, including The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Boy Scout Handbook. Light was provided by oil lamps. Borrowers recorded their loans in a notebook. If someone wanted to contact Richmond, he or she could holler for him using an old phonograph horn, hoping that the wind was blowing in the right direction for him to hear.

Richmond knew the value of a good story. He wrote articles about the library, which he sent to newspaper and magazine editors, and went on publicity tours. A few major publications sent reporters to interview him. A 1952 article in the Saturday Evening Post positively delighted in the tale of a backwoods hermit tending to the literary needs of his hillbilly neighbors. The locals weren’t pleased, going so far as to create the Newton County Betterment Group to fight this unfair portrayal.

Years of rough living and poor diet may have taken their toll, along with the arrival of a regional library system in 1944. In 1953, Richmond married longtime friend Edna Gardner of Texarkana, Texas, whom he had met through the Ozark Artists and Writers Guild. Not long after that, Ted Richmond left his cabin and library and moved to Texarkana. He died there in 1975.

Tourism

Pearl Wilhemina McGowan Holland with a stringer of goggle-eyed perch, largemouth bass, and catfish, by the store at Shady Grove Campground, Pruitt, 1930s. Richard and Melba Holland Collection (S-98-2-340)

“I love it here. . . . You are so close to God you can just see it all around you. The birds sing all the time . . . and you should hear the whippoorwill at night. It’s the most peaceful place in the world.”

Pearl Holland

Tulsa World, June 20, 1965

Today, much of Newton County’s businesses are tourism related. Whether folks are camping in the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests or floating the Buffalo River or riding their motorcycles down scenic Highway 7, tourism dollars are important to the county’s economy.

The area’s rivers, especially the Buffalo, have always drawn anglers. For decades, visitors often stopped at the Shady Grove Campground at Pruitt to fish or swim the Buffalo. The camp was established in 1920 by F. A. Hammons. It offered a bathhouse, bathing suit and towel rentals, campsites, a dance hall, and a well-maintained river sandbar. When the new bridge was built in 1931, Hammons built a few rental cabins on the old bridge. Famous artist Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri was a campground regular. A sign at the camp read, “No hard drinks, shouting or unlawful acts allowed.”

For many years Hammons’ step-daughter Pearl McGowan Holland was the camp’s manager. Pearl’s son, Richard, grew up on the river—swimming, fishing, hunting, and exploring caves. At age 16 he quit school to become a fishing guide for tourists for a time. In 1973 the Holland family made a heartbreaking decision. They sold their land along the Buffalo to the National Park Service. They greatly missed the river and the opportunities the campground gave them to meet new people and visit with old friends.

In Boxley Valley in the late 1930s, Clyde Villines and others worked to clear many years of silt and vegetation out of the millpond which fed his grist and flouring mill. He stocked the revitalized pond with fish and built five small cabins to rent to weekend anglers from Harrison and other nearby towns.

Ponca is the headquarters for folks wanting to float a popular stretch of the Buffalo. On spring and summer weekends the river is lined with canoes and paddlers, many transported to the river by either the Lost Valley Canoe Service or the Buffalo Outdoor Center, the area’s two major outfitters. Locals sometimes see it as an “aluminum stream,” both for the canoes and beer cans that float on by.

In 2004 Randal and Debbie Phillips purchased a few of the buildings at the old Marble Falls ski resort next to Dogpatch, and began transforming them into a motorcycle resort complete with motel and restaurant, convention center, campground, and motorcycle-related shops. The Phillips hope to make Newton County the biker capital of Arkansas.

Whiskey Making

Men with sacks of corn at the Bat House Cave distillery, Wells Creek, near Hasty, 1900s-1910s. Newton County Times Collection (S-88-234-94)

“Several men were lounging around each still, but it was noticeable that none of them were drunk or even drinking. . . . [T]hey probably considered that they were at work, and a man cannot very well get drunk and work at the same time.”

Wayman Hogue

Back Yonder, 1932

For much of the 1800s, making alcohol didn’t require legal permits or taxes. Just the proper equipment, a few sacks of dried corn, and a good supply of water. Aside from the pleasures of home brew, distilling whiskey was a good way to use surplus corn and make some cash.

One of Newton County’s first stills was run by Alfred Carlton at a spring on his father’s homestead near Parthenon. At Henson Creek, John Dale put his still under a rock shelter. For 35 cents a customer could get a large gourd-full of “mountain dew.” Squirrel hunter Tom Reynolds stopped to visit with Dale one day, only to have the stopper from his powder horn pop out as he bent to light his pipe from a cooking fire. After the ignited gunpowder produced a loud bang, Reynolds said, “That White Mule sho do have some kick.”

In 1897 the U.S. government passed the Bottled-in-Bond Act, in part to guarantee that spirits were unadulterated (not diluted or impure). Only legal, government-bonded distilleries were allowed to manufacture and sell alcohol. Revenue stamps were affixed to barrels and bottles to show that the proper taxes had been paid. The taxation caused many distillers to hide their operations from the revenue agents, leading to the rise of moonshining. However, there were two legal distilleries in Newton County. One was Bill McDougal’s distillery near the Big Hurricane Creek.

Over at Bat House Cave at the head of Wells Creek, between Hasty and Yardelle, owners Charles Bethany and Newton Sanders operated their distillery within a natural rock shelter that had a good spring. One way to make whiskey was to soak corn kernels in water for a couple of days and let them sprout. The corn was crushed into bits or “chops” and placed in a wood barrel along with coarse-ground cornmeal to create a mash. After a few days of fermentation the starch in the corn was converted into sugar. The mash was placed in an enclosed metal cooker and heated. The rising steam was trapped in a coiled copper tube or “worm” which was cooled by water. What dripped out as liquid was further cooked and condensed to make whiskey.

The distiller at Bat House was Tom Raney. After fermentation the mash was dumped into a wood trough as hog feed, leading to a few tipsy pigs. Gaugers George Ray and Newt Jones weighed the whisky and placed government stamps on the barrels, proof that the distillery had paid its taxes. The distillery was allowed to make 12 gallons a day.

The distilleries closed in 1917, when Arkansas’ “bone dry” liquor law went into effect, which prohibited the “transportation, delivery, and storage of liquor.” The night Bat House closed, the liquor barrels were stolen from the warehouse. Moonshining continued as national prohibition went into effect in 1920.

Credits

Allen, Eric. “Confederate Powder Cavern Still Looms Above Buffalo.” Southwest Times Record, 11-27-1966.

Arden, Harvey. “America’s Little Mainstream.” National Geographic, Vol. 151, No. 3 (March 1977).

“Arkansas Elk Herd is on the Grow.” Unidentified and undated news clipping (1986). Shiloh Museum research files.

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. “Ponca Elk Education Center.” (accessed 11/2013)

Arkansas Gazette. “Ore in Newton County Spurs Mine Activity.” 12-8-1940.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. “Gould Jones Reservoir, Jasper, Newton County.” (accessed 12/2013)

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. “Jasper Commercial Historic District, Jasper, Newton County.” (accessed 12/2013)

Bethune, Ed. “What price elk? Stop the Bearcat Hollow Project. ” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 8-11-2012.

Blevins, Brooks. “Mountain Mission Schools in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXX, No. 4 (Winter 2011).

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2002.

“Bone Dry” Liquor Law of 1917. FranaWiki. (accessed 11/2013)

Bowden, Bill. “5 environmental groups unite to halt elk habitat expansion.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 8-30-2012.

Bowden, Bill. “Arkansas bridge falling victim to age, upkeep costs.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 12-15-2019. (accessed 3/2020)

Bowden, Bill. “Dogpatch dream dies: Owner of abandoned Arkansas theme park served foreclosure notice.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 12-8-2019. (accessed 3/2020)

Bowden, Bill. “National park working to broaden its diversity.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 6-18-2012.

Branham, Chris. “Section of Arkansas 7 collapses near Jasper.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 8-15-2012.

Braswell, James. “In the Land of a Million Smiles.” Stephen A. Douglas Music Normal Association: Aldrich, MO, 1925.

Buffalo National River, National Park Service. “Whiteley Mill, April 1864.” (accessed 11/2013)

Carroll County Tribune. “Carroll Electric Will Mark Golden Anniversary.” 11-4-1987.

Carroll Electric Cooperative Corporation. “Burdine honored by Electric Cooperatives.” 3-2-2010. (accessed 12/2013; no longer available 3/2020)

Cessna, Ralph. “Library in the Wilderness.” Christian Science Monitor, 4-5-1947.

Charles, Steve. “Ozark Byways.” Ozark Highways, Spring/Summer 1972.

Chestnut. E. F. “Rural Electrification in Arkansas, 1935-1940: The Formative Years.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. XLVI, No. 3 [Autumn 1987].

Christenson, Jeff. “Camp Orr: Summertime Tradition for Scouts.” Harrison Daily Times, 7-28-1988.

Clayton, Joe. “Ted Richmond’s ‘Wilderness Library.'” unidentified and undated news clipping (1950s). Shiloh Museum research files.

Compton, Neil. The Battle for the Buffalo River: A Twentieth-Century Conservation Crisis in the Ozarks. University of Arkansas Press: Fayetteville, 1992.

Craft, Dan. “Boy Scout Camp Turns 50.” Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, 5-25-2003.

Craft, Dan. “Camp Orr Celebrates 50 Years.” Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, 6-20-2003.

Croley, Victor A. “The Battle of Whiteley’s Mill Was Small.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 21, No. 5 (June 1973).

Deane, Ernie. “Multi-Purpose Forests.” Springdale News, 2-25-1981.

Dezort, Jeff. “Camp Orr’s 50th anniversary celebrated.” Newton County Times, 6-26-2003.

Dezort, Jeff. “No. 45: A scenic byway since 1993.” Newton County Times, 4-22-2010.

Dodson, Donna. “Christmas party brought down early courthouse.” Donna Dodson, Newton County Times, 3-18-2010.

“Dogpatch U.S.A.” AbandonedOK. (accessed 11/2013)

“Dogpatch U.S.A.” Arkansas Roadside Travelogue, 4-2-2001.

Edmisten, Bob. “Dogpatch, USA, Growing.” Springdale News, 6-11-1969.

Edson, Arthur. “America the Beautiful: The Ozarks.” Tulsa World, 6-20-1965

Electric Cooperatives of Arkansas. “Our History” [rural electrification]. (accessed 12/2013)

Faris, Ann. “I Didn’t Raise My Family To Live Off Of The Government” [Sutton Handle Factory]. Arkansas Gazette, 10-16-1949.

Faris, Paul. “Ted Richmond.” Ozark Log Cabin Folks. Rose Publishing Co.: Little Rock, 1983.

“Field Report: Skirmish at Whiteley’s Mill.” Major James A. Melton, Second Arkansas Union Cavalry, 4-10-1864, Newton County, Arkansas and the Civil War, Ancestry.com. (accessed 11/2013)

Greenhaw, Clyde. “Exploring a Cave in 1834.” Arkansas Gazette, 2-9-1941.

Haight, Christine. “Sutton Handle Factory: The Beginnings.” Newton County Times, 9-25-1997.

Hanley, Ray and Diane, with the Newton County Historical Society. Images of America: Newton County. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC, 2012.

Hardaway, Billie Touchstone. These Hills, My Home: A Buffalo River Story. Western Printing Co.: Republic, MO, 1980.

Henderson, Shannon. “The Battle of Limestone Valley.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 13, No. 10 (November 1965).

Hogue, Wayman. Back Yonder: An Ozark Chronicle. Minton, Balch and Co.: New York, 1932.

Holland, Richard A. “Ellis & Pearl (McGowan) Holland.” Newton County Family History, Newton County Historical Society: Jasper, 1992.

Holland, Richard A. “Richard Holland.” Newton County Family History. Newton County Historical Society: Jasper, 1992.

Jansma, Harriet. “The Book Man and the Library: A Chapter in Arkansas Library History.” Arkansas Libraries, Vol. 39 (December 1982).

Johnson, Russell T. “Dogpatch USA.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (accessed 11/2013)

Jones, Melissa L. “Patching up Dogpatch.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 2-19-2007.

Lackey, Daniel Boone. “Cutting and Floating Red Cedar Logs in North Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. XIX, No. 4 (Winter 1960).

Lackey, Walter F. “Historical Notes” [lead mining]. Newton County Times, 8-11-1983.

Lackey, Walter F. History of Newton County, Arkansas. S of O Press: Point Lookout, MO, 1950.

Lair, Dwain. “Parthenon Gym Gets New Life From Arkansas.” Harrison Daily Times, undated [1999].

Leith, Sam A. “Diamond Cave—Jasper’s Ace Attraction.” Ozarks Mountaineer, February 1957.

“Logan, Coy. “This I Remember, As It Was Told To Me.” Carroll County Historical Society, Vol. 2, No. 3 (June 1957).

Martin, Meredith. “Three Big Days, Three Big Nights, and One Petrified Indian Baby: Stories from Lurton, Arkansas.” Mid America Folklore, Vol. 28, No. 1-2 (2000).

Mays, Armon. “The Buffalo As A River Of Commerce.” Marshall (AR) Mountain Wave, 1-28-1985.

McCamant, Richard E., and Dwight Pitcaithley. “National Park Service Protects Buffalo River.” Harrison Daily Times, 7-4-1986.

McGeeney, Ryan. “JPs get earful of yeas, nays on hog farm.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 3-6-2013.

McKnight, Edwin T. Zinc and Lead Deposits of Northern Arkansas. U.S. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington D.C., 1935.

Mosby, Joe. “Before the Buffalo Became ‘Aluminum Conveyor Belt.’” Arkansas Gazette, 6-17-1984.

Neal, Joseph C. Mining the Mountains: Pettigrew and Ponca in the Era of Zinc. Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, early 1980s.

Newton County Action Team. Pathways through Newton County, late 1990s.

Newton County Historical Society. “Diamond Cave: A lost Newton County gem.” Newton County Times, 7-21-2010.

Newton County Times. “A Century After Being Pushed West Elk Are Coming Home.” Mid 1980s.

Newton County Times. “Chamber of Commerce holds history of Newton County.” 6-23-2005.

Newton County Times. “Early Stories in the Newton County Times” [REA high-power line]. 12-12-2012.

Newton County Times. “Historic courthouse at center of festival.” 6-26-2003.

Newton County Times. “Historical Notes” [Highway 7]. 6-1-1989.

Newton County Times. “History of Parthenon Academy revisited.” 9-29-2005.

Newton County Times. “Parthenon Preparing to Restore Old Gym.” 2-17-2000.

Newton County Times. “Sale of Diamond Cave to Texas Corporation Announced.” 9-4-1995.

Newton County Times. “Sawmilling, Logging Help Phillips Stay on Farm.” 5-31-1984.

Newtonian. Newton County Academy: Parthenon, 1922.

Ozarks Mountaineer. “Arkansas’ New Parkway—Highway 7 a Scenic Wonder.” Vol. 5, No. 4 (February 1957).

Perkins, J. Blake. “The Arkansas Tick Eradication Murder: Rethinking Yeoman Resistance in the ‘Marginal’ South.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXX, No. 4 (Winter 2011).

Phelps, John E. “Skirmish in Limestone Valley, part 1 and part 2.” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. XXXIV, eHistory, OSU Department of History (accessed 11/2013)

Pierce, Arthur. “Historical Notes” [Newton County Academy]. Newton County Times, 9-1-1988.

Pitcaithly, Dwight. “Zinc and Lead Mining Along the Buffalo River.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXVII, No. 4 (Winter 1978).

Playgrounds in Arkansas. “Diamond Cave, Newton County.” Ozark Playgrounds Association: Joplin, undated [1920s].

Pruitt, Lisa R. “Law and Order in the Ozarks (Part LXXXV): Dogpatch lawsuit finalized.” (accessed 11/2013)

Putthoff, Flip. “Buffalo would be different today without Compton.” Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, 11-8-1999.

Rodman, Mike. “Residents crusade to erase Dogpatch U.S.A.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 2-5-1994.

Rogers, L. M. R. “Orr Scout Camp—Wilderness Paradise in Arkansas.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 4, No. 2, (September 1955).

Rural Arkansas. Untitled article about Kathryn Wheeler [rural electrification]. May 1984.

“S. 2125 (98th): Arkansas Wilderness Act of 1984.” (accessed 11/2013)

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. “Serving Our Clients: Rural Relief in 1930s Newton County.”

Sims, Scarlett. “State seeks to improve Arkansas 7.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 5-31-2011.

Smith, David A. Lead-Zinc Mineralization in the Ponca-Boxley Area, Arkansas. University of Arkansas-Fayetteville, 1978.

Smith, George S. “Capp to Open Dogpatch.” Baxter (Mountain Home, AR) Bulletin, 5-16-1968.

Smith, Kenneth L. “Highest Cliff in All Arkansas.” Arkansas Democrat, 12-6-1959.

Smith, Kenneth L. “The Seven Kettles—Actually There Were Eight—And the Confederates Put Them to Good Use.” Arkansas Gazette, 11-20-1959.

Spence, Hartzell. “Modern Shepherd of the Hills.” Saturday Evening Post, 11-8-1952.

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie. “Cherokee.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas (accessed 3/2020).

Stroud, Raymond B., et al. Mineral Resources and Industries of Arkansas. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington D.C., 1969.

Suter, Mary. “Rural Electrification.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (accessed 12/2013)

Teter, Rhonda. “Newton County Academy.” Newton County Times, 9-7-2011.

Treiber, Peggy. Newton County slide show, produced on behalf of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, 6/2/1989.

“Tumbling Tumbleweeds” thread [re Jubilation T. Cornpone statue]. (accessed 11/2013; no longer available 3/2020)

“Twilight Trail an Eerie Place,” unidentified and undated news clipping (1950s). Shiloh Museum research files.

Walkenhorst, Emily. “C and H Hog Farms takes state buyout; $6.2M deal cut to preserve Buffalo River.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 6-14-2019. (accessed 3/2020)

Wallworth, Adam. “Graze anatomy: Do elk crowd cattle?” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 5-9-2010.

Wallworth, Adam. “Newton County signs in sight.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette 4-5-2012.

Wallworth, Adam. “Residents hear options on cutting elk numbers.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 7-14-2010.

Whayne, Jeannie. “Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (accessed 11/2013)

Wilson, Ruth. “Elk returning to native habitat.” Arkansas Gazette, 2-11-1985.

Wood, Mary. “Ozark-St. Francis National Forests.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (accessed 12/2013)

19th-Century Settlement