Settling the Ozarks

Core ExhibitA large tract of land including what is now Northwest Arkansas was, for a time, the hunting grounds of the Osage Indians. Beginning in the late 1700s, increasing settlement by Euro-Americans in and around the Cherokee homeland in southern Appalachia led some tribal members to look for new land in what would become Arkansas Territory. Over the years additional Indian settlers came and by the 1810s had established farmsteads, orchards, and mills in the northwest quarter of the territory. In an effort to keep the peace between the Cherokees and the Osage, land purchases were made and boundaries redrawn. But the white settlers and politicians of the Arkansas Territory wanted the fertile valleys and timberland for themselves. In 1828 the land was opened officially for settlement.

Those Who Came

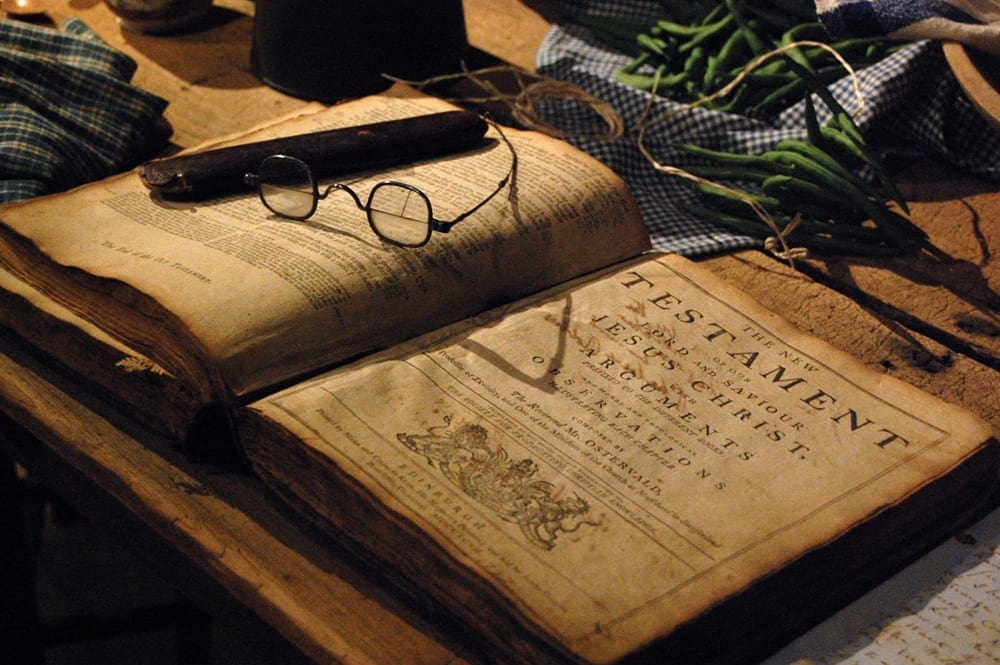

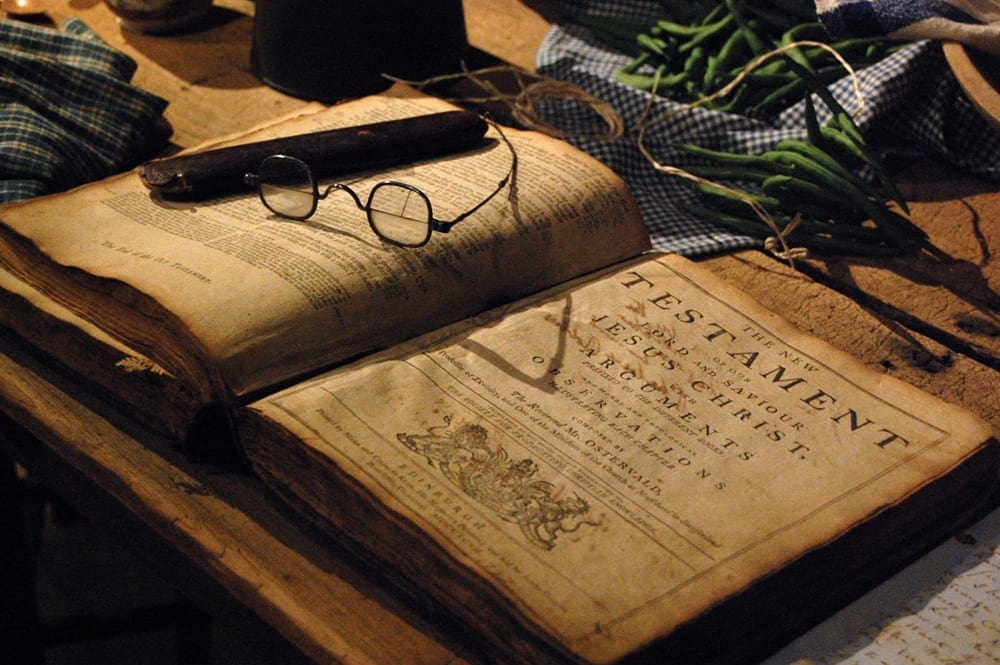

The early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They came in oxen-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a piece of land to call their own.

The early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They came in oxen-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a piece of land to call their own.

The majority of new settlers in the Arkansas Ozarks prior to the Civil War came from Missouri and the Upland South (southern Appalachia) including Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia. Most were native-born Americans of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Not all settlers came of their own free will. Some were enslaved workers. Although slavery wasn’t as widespread in northern Arkansas as it was in the South, many conditions were similar. Children and adults were denied their freedom and forced to work, all for the benefit of their enslavers, often influential citizens made wealthy through the labor of others. Most settlers didn’t enslave workers, not necessarily because they condemned the institution of slavery, but because the cost of such workers was beyond their means. During the 1830s thousands of Cherokees still living in the east, their enslaved people, and members of other eastern tribes endured forced removal to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) on Northwest Arkansas’s western border. Their journey is now known as the “Trail of Tears.”

Living Off the Land

A settler’s first permanent shelter was often made of logs, such as the Lewis-Reed cabin (a portion of which is on exhibit). It was built in 1841 by Hugh Lewis in what was called “Boone’s Grove,” near present-day Elkins. Lewis came to Washington County from Missouri in 1831. By 1840, he and his wife Harriet had five children and 240 acres, including good bottom land for farming. The cabin changed hands twice more before it was bought by Alexander and Elizabeth Reed in 1866. Alexander was born in Tennessee and came to Northwest Arkansas in 1852. Elizabeth’s father William McGarrah came to Arkansas in 1826 from South Carolina and was one of Fayetteville’s first white settlers.

A settler’s first permanent shelter was often made of logs, such as the Lewis-Reed cabin (a portion of which is on exhibit). It was built in 1841 by Hugh Lewis in what was called “Boone’s Grove,” near present-day Elkins. Lewis came to Washington County from Missouri in 1831. By 1840, he and his wife Harriet had five children and 240 acres, including good bottom land for farming. The cabin changed hands twice more before it was bought by Alexander and Elizabeth Reed in 1866. Alexander was born in Tennessee and came to Northwest Arkansas in 1852. Elizabeth’s father William McGarrah came to Arkansas in 1826 from South Carolina and was one of Fayetteville’s first white settlers.

For most settlers, living off the land was hard work, day in and day out. Everyone had a role to play if the family was to survive and prosper. Men and older boys cleared land to plow and plant fields of food crops. They built homes and barns, hunted wild game, slaughtered hogs, repaired fences, chopped firewood, made tools, tanned leather, built furniture, and tended livestock. Women and older girls preserved food and prepared three meals a day. They raised children, spun fiber and wove it into cloth, sewed clothing and household linens, made soap and candles, washed laundry, killed and plucked chickens, tended the vegetable garden, and gathered wild plants for food and medicine. Young children had chores as well. They helped haul water and harvest crops, picked seeds from cotton bolls, weeded the garden, fed livestock, and scraped the hair from scalded hogs. Most importantly, they learned the skills needed for life on the frontier.

The first industries in the area took advantage of the abundant wildlife. Hunters killed deer, raccoon, fox, beaver, and other animals for their pelts. Bears were taken for meat and fur, but more importantly for fat, which was rendered to make fuel for oil lamps, lubricants, and even hair gel. As communities grew, specialty businesses sprung up. Millers ground corn and wheat, tanners cured leather and fashioned shoes, cabinetmakers crafted furniture, and blacksmiths shod horses and made tools.

Making a Community

There were no free, state-sponsored public schools in Arkansas until after the Civil War. While most children did not attend school, some were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic at home. There were a few short-term, fee-based schools scattered about, run by ministers or teachers (usually men, often with limited schooling themselves). For enslaved African Americans, education wasn’t illegal, but it wasn’t encouraged. Those few who were taught to read often learned their letters from the Bible, as a pathway towards Christianity. Well-to-do Cherokee and Choctaw families sent their children to be educated at the Fayetteville Female Seminary, along with the children of well-to-do whites. But the Indians faced prejudice, both from the community and from white parents, some of whom moved their girls to another school.

There were no free, state-sponsored public schools in Arkansas until after the Civil War. While most children did not attend school, some were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic at home. There were a few short-term, fee-based schools scattered about, run by ministers or teachers (usually men, often with limited schooling themselves). For enslaved African Americans, education wasn’t illegal, but it wasn’t encouraged. Those few who were taught to read often learned their letters from the Bible, as a pathway towards Christianity. Well-to-do Cherokee and Choctaw families sent their children to be educated at the Fayetteville Female Seminary, along with the children of well-to-do whites. But the Indians faced prejudice, both from the community and from white parents, some of whom moved their girls to another school.

Churches were great civilizing forces on the frontier. In Northwest Arkansas, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist churches were the earliest and largest groups. Typically, church members first met in homes, then progressed to one-room log buildings and, later, frame churches. In the years before the Civil War, the issue of slavery was debated by all churches. In many churches debate led to division along North-South lines. Some churches accepted African-American members, who were probably segregated in worship from their fellow white congregants.

Early doctors generally received training by studying under a recognized physician. Some attended medical school. Doctors who practiced “eclectic medicine” believed that the medical treatments of the day—bleedings, purgings, and freezing baths—were too harsh. Instead, they relied on plants and other ingredients (including soap, gunpowder, and earthworms!) to treat ailments. “Granny women” and midwives ministered to the people as well. Tea made from the roots of the sassafras tree was drunk in the springtime to thin the blood and dried mullein leaves were smoked in a pipe to cure a cough.

A large tract of land including what is now Northwest Arkansas was, for a time, the hunting grounds of the Osage Indians. Beginning in the late 1700s, increasing settlement by Euro-Americans in and around the Cherokee homeland in southern Appalachia led some tribal members to look for new land in what would become Arkansas Territory. Over the years additional Indian settlers came and by the 1810s had established farmsteads, orchards, and mills in the northwest quarter of the territory. In an effort to keep the peace between the Cherokees and the Osage, land purchases were made and boundaries redrawn. But the white settlers and politicians of the Arkansas Territory wanted the fertile valleys and timberland for themselves. In 1828 the land was opened officially for settlement.

Those Who Came

The early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They came in oxen-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a piece of land to call their own.

The majority of new settlers in the Arkansas Ozarks prior to the Civil War came from Missouri and the Upland South (southern Appalachia) including Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia. Most were native-born Americans of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Not all settlers came of their own free will. Some were enslaved workers. Although slavery wasn’t as widespread in northern Arkansas as it was in the South, many conditions were similar. Children and adults were denied their freedom and forced to work, all for the benefit of their enslavers, often influential citizens made wealthy through the labor of others. Most settlers didn’t enslave workers, not necessarily because they condemned the institution of slavery, but because the cost of such workers was beyond their means. During the 1830s thousands of Cherokees still living in the east, their enslaved people, and members of other eastern tribes endured forced removal to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) on Northwest Arkansas’s western border. Their journey is now known as the “Trail of Tears.”

Living Off the Land

A settler’s first permanent shelter was often made of logs, such as the Lewis-Reed cabin (a portion of which is on exhibit). It was built in 1841 by Hugh Lewis in what was called “Boone’s Grove,” near present-day Elkins. Lewis came to Washington County from Missouri in 1831. By 1840, he and his wife Harriet had five children and 240 acres, including good bottom land for farming. The cabin changed hands twice more before it was bought by Alexander and Elizabeth Reed in 1866. Alexander was born in Tennessee and came to Northwest Arkansas in 1852. Elizabeth’s father William McGarrah came to Arkansas in 1826 from South Carolina and was one of Fayetteville’s first white settlers.

For most settlers, living off the land was hard work, day in and day out. Everyone had a role to play if the family was to survive and prosper. Men and older boys cleared land to plow and plant fields of food crops. They built homes and barns, hunted wild game, slaughtered hogs, repaired fences, chopped firewood, made tools, tanned leather, built furniture, and tended livestock. Women and older girls preserved food and prepared three meals a day. They raised children, spun fiber and wove it into cloth, sewed clothing and household linens, made soap and candles, washed laundry, killed and plucked chickens, tended the vegetable garden, and gathered wild plants for food and medicine. Young children had chores as well. They helped haul water and harvest crops, picked seeds from cotton bolls, weeded the garden, fed livestock, and scraped the hair from scalded hogs. Most importantly, they learned the skills needed for life on the frontier.

The first industries in the area took advantage of the abundant wildlife. Hunters killed deer, raccoon, fox, beaver, and other animals for their pelts. Bears were taken for meat and fur, but more importantly for fat, which was rendered to make fuel for oil lamps, lubricants, and even hair gel. As communities grew, specialty businesses sprung up. Millers ground corn and wheat, tanners cured leather and fashioned shoes, cabinetmakers crafted furniture, and blacksmiths shod horses and made tools.

Making a Community

There were no free, state-sponsored public schools in Arkansas until after the Civil War. While most children did not attend school, some were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic at home. There were a few short-term, fee-based schools scattered about, run by ministers or teachers (usually men, often with limited schooling themselves). For enslaved African Americans, education wasn’t illegal, but it wasn’t encouraged. Those few who were taught to read often learned their letters from the Bible, as a pathway towards Christianity. Well-to-do Cherokee and Choctaw families sent their children to be educated at the Fayetteville Female Seminary, along with the children of well-to-do whites. But the Indians faced prejudice, both from the community and from white parents, some of whom moved their girls to another school.

Churches were great civilizing forces on the frontier. In Northwest Arkansas, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist churches were the earliest and largest groups. Typically, church members first met in homes, then progressed to one-room log buildings and, later, frame churches. In the years before the Civil War, the issue of slavery was debated by all churches. In many churches debate led to division along North-South lines. Some churches accepted African-American members, who were probably segregated in worship from their fellow white congregants.

Early doctors generally received training by studying under a recognized physician. Some attended medical school. Doctors who practiced “eclectic medicine” believed that the medical treatments of the day—bleedings, purgings, and freezing baths—were too harsh. Instead, they relied on plants and other ingredients (including soap, gunpowder, and earthworms!) to treat ailments. “Granny women” and midwives ministered to the people as well. Tea made from the roots of the sassafras tree was drunk in the springtime to thin the blood and dried mullein leaves were smoked in a pipe to cure a cough.