Timber!

Online ExhibitThe Great Forest

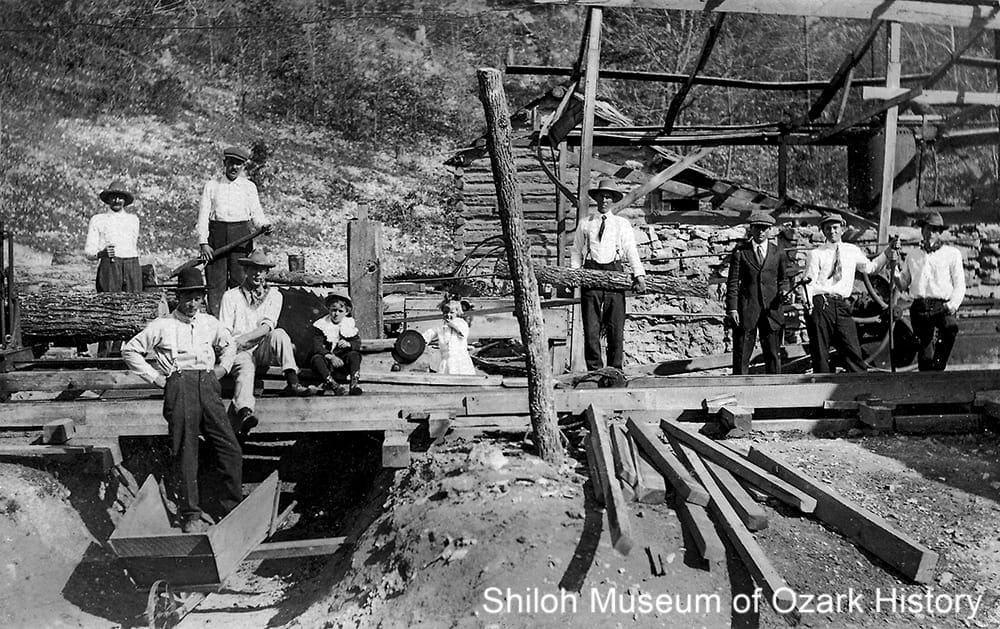

Albright sawmill workers, Red Star (Madison County), 1918–1920. The white-oak logs came from the Fitch place on Reeves Mountain. They were 12 feet long, 44 inches in diameter, and each produced over 1,200 board feet of lumber. The logs were so heavy they had to be brought to the sawmill on a heavy-duty boiler wagon. Back, from left: Nathan Ward, Virgil Holland, and Newt Ward. Front, from left: Squire Eaton, Bill Killian, Demps Ward (barely visible), Dave Samuels, Jim Eaton (seated on ground), and Lewis Samuels. Frank Eaton Collection (S-87-55-20)

To the newly arrived settler, the Arkansas Ozarks offered many resources for building a new life. The area’s vast stands of virgin forest were full of possibilities. Timber was used for building structures and furnishings, for heating homes and cooking food, and as a way to earn cash by making roof shingles and other products for sale. A few entrepreneurs built sawmills, selling lumber and trim to homebuilders.

The timber industry began in earnest around 1881 when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad (the “Frisco”) steamed through Benton and Washington Counties. The line was built in part because of the great demand in other markets for railroad ties and mine props. The rich forests of the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks were the last source of timber this side of the vast western prairies. Eager settlers and expanding railroads needed the wood to build homes and rail lines. With the coming of the Frisco, increased transportation and business opportunities meant new growth for the region. Soon other railroads and branch lines sprung up. Farmers and businessmen rushed to harvest the forests.

Albright sawmill workers, Red Star (Madison County), 1918–1920. The white-oak logs came from the Fitch place on Reeves Mountain. They were 12 feet long, 44 inches in diameter, and each produced over 1,200 board feet of lumber. The logs were so heavy they had to be brought to the sawmill on a heavy-duty boiler wagon. Back, from left: Nathan Ward, Virgil Holland, and Newt Ward. Front, from left: Squire Eaton, Bill Killian, Demps Ward (barely visible), Dave Samuels, Jim Eaton (seated on ground), and Lewis Samuels. Frank Eaton Collection (S-87-55-20)

The Great Forest

To the newly arrived settler, the Arkansas Ozarks offered many resources for building a new life. The area’s vast stands of virgin forest were full of possibilities. Timber was used for building structures and furnishings, for heating homes and cooking food, and as a way to earn cash by making roof shingles and other products for sale. A few entrepreneurs built sawmills, selling lumber and trim to homebuilders.

The timber industry began in earnest around 1881 when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad (the “Frisco”) steamed through Benton and Washington Counties. The line was built in part because of the great demand in other markets for railroad ties and mine props. The rich forests of the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks were the last source of timber this side of the vast western prairies. Eager settlers and expanding railroads needed the wood to build homes and rail lines. With the coming of the Frisco, increased transportation and business opportunities meant new growth for the region. Soon other railroads and branch lines sprung up. Farmers and businessmen rushed to harvest the forests.

Removing the Forest

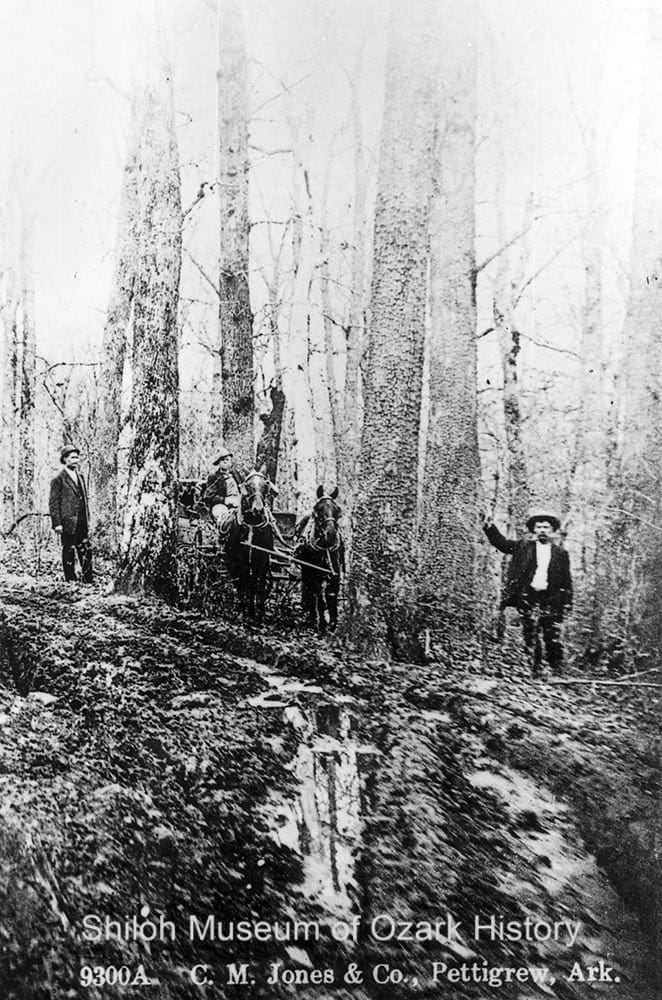

When the first settlers came to Northwest Arkansas, they found forests thick with large, ancient trees—one-hundred-foot-tall white oaks, red cedar trees two to four feet in diameter, huge stands of hickory and walnut flanking the hillsides. The settlers cleared the land for crops and used the timber to build new lives. Then the railroads came, opening new markets for the region’s greatest natural resource.

Hardwoods were the first to be logged, the old-growth timber perfect for railroad ties and mine props. Commercial uses were found for other woods—ash and hickory for making tool handles, locust for making fence posts. In Newton County red cedar trees were virtually ignored until 1903, when the Houston, Ligett and Canada Cedar Company began harvesting them and floating the logs down the Buffalo River to Searcy County, over 50 miles downstream. All that hard and dangerous work to make pencils!

“Many thousands of acres of valuable farm lands [have been opened up] . . . Hence, the removal of our vast forest is merely opening the way for greater possibilities.”

Green Forest Tribune, 1913

Sawmill near the Little Buffalo River, Possum Hollow (Newton County), 1900s–1910s. On the left stands a wagonload of logs waiting to be off-loaded onto the skids (center), before being rolled onto the log carriage. A ramshackle shed offers weather protection to the mill equipment inside. In the foreground boards are loosely stacked for air-drying. Richard and Melba Holland Collection (S-98-2-403)

Once an area had been heavily logged of the first- and second-growth timber, there often wasn’t enough vegetation to hold back erosion. Soil washed down the hillsides, exposing bare rock. Habitat for animals was destroyed and new plant species took over. Some folks tried to farm these areas or use them for grazing animals, but found it difficult. In some places the land was left to heal itself. In others it was burned to clear vegetation after which low-value plants (at least in the lumberman’s eyes) moved in.

Others thought to “reclaim” the land for different purposes. Scientists with the U.S. Soil Conservation Service and other agencies believed that the “low-grade” trees in “much of the so-called Ozark Forest [was] not true forest.” In 1953, at a time when Texas and other southwestern states were experiencing drought, cattlemen looked to the Arkansas Ozarks and neighboring states as possible places to graze their herds. They bought Arkansas land and sprayed chemicals to kill off blackjack and post oaks and other “useless” scrub plants to allow bluestem and other native grasses to grow.

“If trees were planted on this land, and even down in the fertile valleys, the seed would come up and grow. It is too bad the landowners and others did not look to the future of reforesting the cedar brakes.”

Daniel Boone Lackey

Newton County Homestead, April 1960

Boomtowns and Lumber Barons

Stacks of railroad ties, split-rail fencing, and boards await shipment in downtown Pettigrew (Madison County), 1900s–1910s. R. W. Schroll Collection (S-89-51-20)

For a time it seemed that anyone with a saw could turn hard work into a fortune. Near War Eagle (Benton County), Peter Van Winkle and his enslaved workers began a lumber empire in the 1850s, supplying material for many fine area homes. Over in Carroll County in the late 1870s, Franizisca Massman and her logging crews were hurriedly chopping down trees (sometimes without the landowner’s permission) in the fast-growing town of Eureka Springs. By 1887 Hugh F. McDanield of Washington County had exported over $2 million in railroad ties at about 25 cents each. That’s about eight million ties!

McDanield was among the first to exploit the railroad. He bought thousands of acres of land along the Frisco and sent out his loggers. Once he exhausted the resources of southern Washington County he looked east. In 1886 he began building a railroad line from Fayette Junction to Madison County (later the St. Paul branch of the Frisco), sparking a string of lumber boomtowns like Baldwin, Elkins, Durham, Crosses, Delaney, Patrick, Combs, and St. Paul. People flocked to the hills to get in on the action. Towns sprang up overnight with all the amenities of bigger cities. At one time St. Paul had three hotels, a number of businesses and churches, a baseball team, a brass band, and twelve nearby sawmills. Today its population is less than 200.

A few miles east of St. Paul, Pettigrew sprang up virtually overnight because of the logging industry. Although the town’s population was small, a number of businesses were started to meet the needs of the lumber industry and offer amenities to the surrounding population. Since Pettigrew was the end of the line for the Frisco’s St. Paul branch, lumber from the surrounding hills and communities was brought there and piled as closely as possible to the railroad tracks to make loading easier. Lightweight fence posts could be loaded easily by teenage boys but it took strong men to load the heavy railroad ties. At the Frisco tie yard in Rogers in the early 1900s, it was said the African-American workers were able to load ties singlehandedly. Unlike the rest of the local black population, which was sometimes harassed or threatened in those days, these tough men were left alone.

Saturdays were often busy as that was the day many folks hauled their lumber into town to sell. They took their payment vouchers to the bank, cashed them in, purchased food and supplies, and perhaps grabbed a bite to eat at a café. In the morning a bank’s cash reserves were depleted; by evening they had been replenished, thanks to the merchants depositing the day’s take.

“Before noon wagons were lined for from a quarter to a mile along all roads heading into town. At times the timber was stacked so high that only a narrow road remained for wagons to move between.”

Robert G. Winn

Northwest Arkansas Times, March 10, 1986

Boomtowns and Lumber Barons

Stacks of railroad ties, split-rail fencing, and boards await shipment in downtown Pettigrew (Madison County), 1900s–1910s. R. W. Schroll Collection (S-89-51-20)

For a time it seemed that anyone with a saw could turn hard work into a fortune. Near War Eagle (Benton County), Peter Van Winkle and his enslaved workers began a lumber empire in the 1850s, supplying material for many fine area homes. Over in Carroll County in the late 1870s, Franizisca Massman and her logging crews were hurriedly chopping down trees (sometimes without the landowner’s permission) in the fast-growing town of Eureka Springs. By 1887 Hugh F. McDanield of Washington County had exported over $2 million in railroad ties at about 25 cents each. That’s about eight million ties!

McDanield was among the first to exploit the railroad. He bought thousands of acres of land along the Frisco and sent out his loggers. Once he exhausted the resources of southern Washington County he looked east. In 1886 he began building a railroad line from Fayette Junction to Madison County (later the St. Paul branch of the Frisco), sparking a string of lumber boomtowns like Baldwin, Elkins, Durham, Crosses, Delaney, Patrick, Combs, and St. Paul. People flocked to the hills to get in on the action. Towns sprang up overnight with all the amenities of bigger cities. At one time St. Paul had three hotels, a number of businesses and churches, a baseball team, a brass band, and twelve nearby sawmills. Today its population is less than 200.

A few miles east of St. Paul, Pettigrew sprang up virtually overnight because of the logging industry. Although the town’s population was small, a number of businesses were started to meet the needs of the lumber industry and offer amenities to the surrounding population. Since Pettigrew was the end of the line for the Frisco’s St. Paul branch, lumber from the surrounding hills and communities was brought there and piled as closely as possible to the railroad tracks to make loading easier. Lightweight fence posts could be loaded easily by teenage boys but it took strong men to load the heavy railroad ties. At the Frisco tie yard in Rogers in the early 1900s, it was said the African-American workers were able to load ties singlehandedly. Unlike the rest of the local black population, which was sometimes harassed or threatened in those days, these tough men were left alone.

Saturdays were often busy as that was the day many folks hauled their lumber into town to sell. They took their payment vouchers to the bank, cashed them in, purchased food and supplies, and perhaps grabbed a bite to eat at a café. In the morning a bank’s cash reserves were depleted; by evening they had been replenished, thanks to the merchants depositing the day’s take.

“Before noon wagons were lined for from a quarter to a mile along all roads heading into town. At times the timber was stacked so high that only a narrow road remained for wagons to move between.”

Robert G. Winn

Northwest Arkansas Times, March 10, 1986

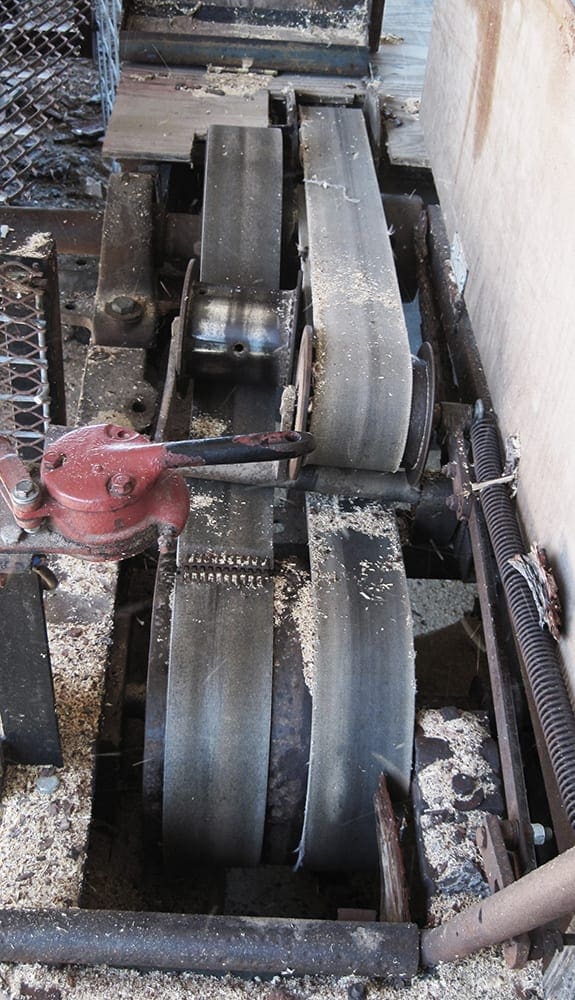

How a Sawmill Works

There are many steps involved in turning a log into boards. An engine [1] turns a mandrel (a kind of spindle) which causes several pulleys and belts [2] to turn. The mandrel operates the circular saw blade [3], the pulley and cables [4] which moves the carriage [5] on its track, and sometimes a dust doodler [6], which is used to remove sawdust from underneath the blade.

The sawyer pulls a lever to operate the rack-and-pinion setworks [7] which move the headblocks [8] (upright supports for the log) on the carriage into place. A log is placed against the headblocks [9] and dogs (sharp metal points) [10] are pushed into the log to keep it secure. A gauge [11] is used to measure the thickness of the cut. The sawyer moves a lever [12] to bring the carriage and log towards the saw blade. The blade cuts into the log [13] and takes off a slab of bark.

The carriage is moved backwards, the log is turned and dogged into place [14], and the setworks are readjusted to bring the log in line with the saw blade. The log is sent through the blade again [15] and the process repeated until the log is square. Then it is cut into boards which are removed by the “off-bearer” [16]. The finished boards and waste slabs [17] are ready to be piled.

"Portable" Sawmills

Moving the Johnson sawmill’s boiler from Red Star (Madison County), about 1920. Oscar Bennett rides the mule nearest the wagon. Rope has been used to help stabilize the heavy, round boiler on the wagon. Jim Bennett Collection (S-96-38-8)

When Northwest Arkansas lumber baron Peter Van Winkle rebuilt his sawmill after the Civil War, the huge steam boilers and other heavy equipment he purchased in St. Louis were shipped down the Mississippi River and then up the Arkansas River to Van Buren. From there they were loaded onto oxcarts and hauled over the Boston Mountains. There were few roads then. The men had to hack their way through the forest and ford dangerous streams. As one worker said, it was “a nightmare every foot of the journey.” In a time before paved roads and gasoline-powered vehicles, horses and mules were used to transport logs, lumber, and sawmill equipment from forest to mill to railroad depot. Sure-footed animals were able to navigate the rocky and hilly mountains. Even after logging trucks began to be used, mules were sometimes needed to pull a stuck vehicle from a muddy rut in the road.

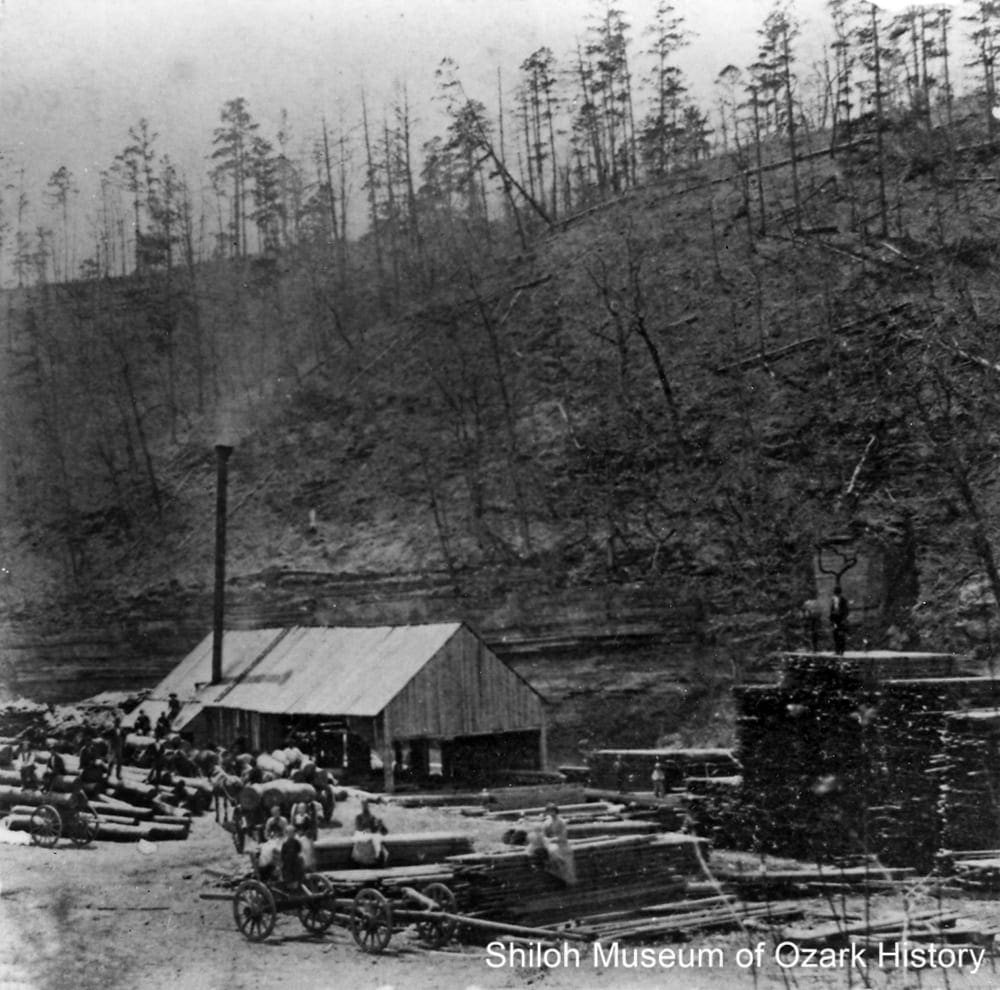

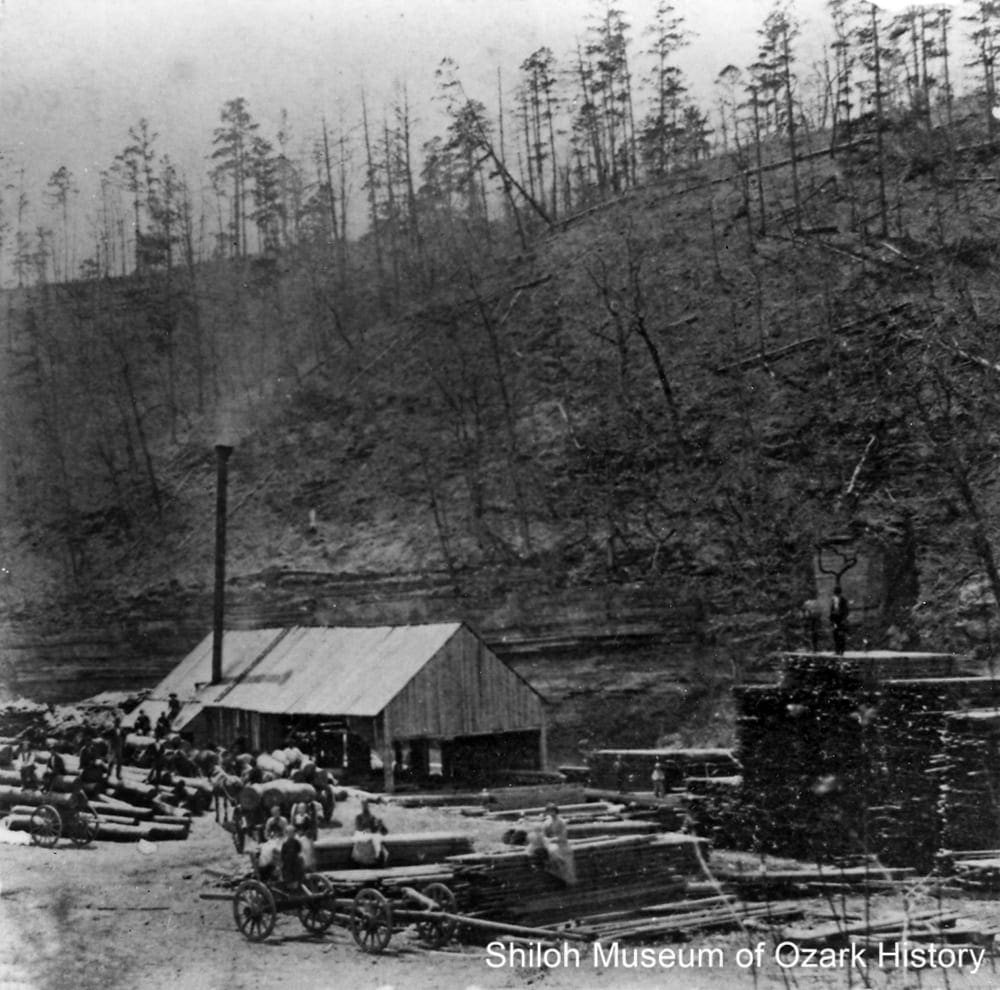

Sawmill, Bentonville/Hiwasse area (Benton County), 1900s-1910s. Wagons loaded with logs and boards wait near the mill set (center) which is powered by a steam engine (right). A large pile of sawdust sits nearby. Monte Harris Collection (S-86-319-80)

Most of the area’s sawmills were temporary. The mill set (the engine, saw blade, tracks, and carriage) were set up where timber and water for the boiler were plentiful. When the trees were depleted, the equipment was packed up and moved to the next location.

“[As a “dust doodler”] I had to keep the sawdust out from under the saw. . . .We would fill a number three washtub with dust, drag it away from the saw, dump it, then go back and fill it again. This went on all day—a pretty tough job for a six-year-old.”

Farrel Henson

White River Valley News, September 7, 2000

Sawyers and Sawmills

Sawmill, Hickory Creek (Benton County), 1910s. The sawyer stands near the edge of the log carriage and saw blade (left). Underneath is a pit where sawdust collects. At center a man holds a slab of wood removed from the log. On the right sits an upright boiler on a long, stone firebox. The engine and flywheel used to operate the machinery can be seen behind the men on the right. Don Reynolds Collection (S-2005-11-5)

A good sawyer worked quickly to keep from wasting time and energy. He constantly evaluated the log he was working, deciding which way to turn it, watching for hidden problems like rot or knotholes. A wrong decision would mean the loss of valuable lumber.

Children often worked in the timber woods and at the sawmill. And just like the men’s work, their work was long, exhausting, and sometimes dangerous. Young boys moved logs around, hauled wood for the boilers, and took care of the mounting pile of sawdust. Sometimes whole families worked at the mill. When she was a young girl in the early 1920s, Ruby Norton Watson of Newton County lived in a stave-bolt camp with her parents. Every morning she had to make the beds in the mill hands’ tents and sweep the floor. For fun she and the other kids in camp would play on the huge pile of staves. The shifting pile of wood was a dangerous place. According to Ruby, if the kids had fallen, “it would have killed them.”

“My dad [Orville Martin] went to work as soon as he was big enough to work—fifteen or sixteen—doing a man’s work every day. Boys that age would be put on one end of a crosscut saw—a “misery whip,” they called it—with an older man on the other end of the saw. . . . The old men took advantage of the boys, working the living God out of them. It made them tough, I guess.”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

Sawmill, Goshen (Washington County), 1900s–1910s. The men in front hold cant hooks (metal hooks on wood poles) to turn the log on the carriage. Attached to the upright headblocks on the carriage are “dogs” which hold the log in place. Ruth Flanagan Collection (S-84-234-6)

“When the sawyer sends the log through the saw you catch the slab that’s been sawed off, throw it in one pile, and turn back in time to grab up each eight-foot section of one-by or two-by and stack ‘em. . . . [Off-bearing is] not only a tough job, it’s a dangerous one. I’ve seen splinters of wood driven two or three inches into a shed wall.”

Farrel Henson

White River Valley News, September 7, 2000

Inside the Sawmill

Firing the boiler at the Albright sawmill, Red Star, (Madison County), 1930s. The round, metal boiler is seen next to the shoulder of the fireman who appears to be wearing a key-operated clock used to record various duties. The engine’s flywheel is seen in the shadows on the right. Otto Bennett Collection (S-99-66-750)

Early sawmills were powered by steam. A round, metal boiler was placed in a stone or brick enclosure or balanced on a few logs. Slabs and other scrap wood were fed into the firebox underneath the water-filled boiler. The resulting heat turned the water into steam. Steam pressure forced pistons to move, which then powered the sawmill blade and other machinery. Exhausted steam left through a tall flue pipe. If the boiler ran out of water the pressure would build quickly, causing the boiler to explode.

The boiler wasn’t the only danger. With a huge quantity of sawdust flying in the air, scrap wood piled everywhere, and a boiler needing constant supervision, fire was a constant danger. Many mills burned down. Sawyers lost fingers, hands, and more due to distraction, stuck pieces of wood, or equipment failure. At the Johnson mill in Madison County, Richmond Johnson lost two fingers at the cutoff table saw while his brother, Will, lost one on the bandsaw. Their father Noah lost a finger to another machine. In Prairie Grove (Washington County), Henry Brotherton was killed in 1915 when he fell against a circular saw while trying to reset the log carriage back on its track. He was cut into three pieces.

“Green Burgess and Luker [Luke] Carter were killed instantly about noon Tuesday near Wharton [Madison County] when the boiler of a sawmill [exploded]. . . . Burgess was blown through the roof of the mill shed and his horrible mangled body fell only a few feet from where he had stood. Both legs were broken, one ear about torn off, and his head and face practically bursted open. Carter was found about fifty yards from the mill, having been hurled over a fence into a potato patch. . . . So terrific was the explosion that the boiler was blown about 25 feet from its base.”

Rogers Democrat, August 26, 1915

First Wagons, Then Trucks

Samuel Arthur “Buddie” Bivens holding the leading reins of a log wagon, possibly Pruitt (Newton County), 1910s–1920s. Richard and Melba Holland Collection (S-98-2-227)

Horses and mules were critical in the logging industry. They “snaked” (dragged) newly cut logs out of the woods, pulled lumber wagons, and moved mill sets from place to place. Out in the timber woods, some mules were accustomed to the sound of falling trees and wouldn’t react, but others would get spooked. Some animals were smart and patiently backed up to the log, ready to be hitched to the sled dog, a tool used to grab hold of the log. It was important for the mule driver to be uphill of the log, just in case the animal decided to bolt forward once it was hitched to the log.

In Carroll County in the 1920s, Darius Quigley was proud of his matched teams of Belgian Red draft horses. Sometimes the horses would get spooked and run away while they were hitched to the wagon, scattering lumber everywhere. On one occasion, the wagon nudged too closely to the team before the brakes could be applied. The animals ran two miles home before they could be stopped.

“The road such as it was went up the creek bed to the foot of the hill, and then up a long steep hill. It was about all those poor mules could do to pull that loaded wagon up the hill . . . After a lot of grunting and pushing and resting . . . we finally got to the cross tie yard at Winslow.”

Raymond L. Jones

Washington County Observer, December 10, 1981

Rufie Martin’s logging truck at the Martin sawmill, Pettigrew, 1928. S. D. Albright bought this and a similar truck in 1919 for use at his sawmill in Red Star. Martin later got both trucks after they had been beaten up while working the timber. He salvaged enough parts to make one truck. Wayne Martin Collection (S-85-322-44)

The gasoline-powered engine transformed the lumber industry. What was once done by man and beast now could be accomplished more quickly with engines. Beginning in the early 1900s trucks replaced mule-driven wagons. Old steam boilers made way for gas or diesel engines. Drag saws (reciprocating power saws) were the forerunners of chain saws. At six-feet long and weighing around 300 pounds they weren’t terribly portable, but they made quick work when bucking (cutting) logs to length. The first mills were steam powered, but later ran on gas.

Rail Transport

Log train at J. H. Phipps Lumber Company, Fayetteville (Washington County), 1912. Burch Grabill, photographer. Robert Saunders Collection (S-96-2-452)

J. H. Phipps started as a railway agent in St. Paul (Madison County) on the newly built Frisco branch line. Watching car after railroad car of lumber being shipped out, he realized he was in the wrong business. He and a partner started their own lumber company, where they would “work up the raw material into what the world wanted.” By 1898 the business was headquartered in Fayetteville. In a 15-year time period 15,000 cars of logs were shipped in, with 6,164 cars of finished product shipped out. At times there were more than 200 workers.

Phipps was just one of the many hardwood milling operations in the Fayette Junction area, southwest of Fayetteville. Others included the Sligo Wagon Wood Company, the Charlesworth Hardwood Lumber Company (handles), Pitkin and Mayes (wagon parts), and the J. P. Bower Walnut Veneer and Lumber Company. When Addie Lee Lister was a little girl in 1922, she used to sneak off to the Bower mill’s “log bath,” even though her mother forbade her to go. Standing on the concrete walk around the open vat, she was fascinated by the giant walnut logs bobbing around in the bubbling hot water. Soaking off the bark was the first step in turning the wood into veneer, thin sheets of wood used in furniture making.

“Those industries which have to do with the manufacture of various articles from hard wood timber are probably among Fayetteville’s most important enterprises. There are four factories devoted to the manufacture of wood wagon materials alone. Their product is shipped to many foreign parts . . . as well as to every large manufacturing center in our own country.”

Fayetteville City Directory, 1904

J. A. C. Blackburn’s planing mill and a Frisco Railroad train, Rogers (Benton County), 1890s. Marilyn Larner Hicks Collection (S-99-66-504)

James Austin Cameron Blackburn succeeded his father-in-law Peter Van Winkle as the “lumber king” of Benton County. He managed the sawmill near War Eagle for many years and also ran a lumberyard and planing mill in Rogers, starting in 1881, when the first train steamed into town.

From her childhood home east of Rogers, Sadie Trimble saw great teams of horses and mules bringing unfinished boards from War Eagle to town. The mill could produce 20,000 board feet of lumber daily. By 1889 annual output was over three million feet. When Blackburn finally moved to Rogers he found that it was cheaper to supply his operations with materials from his other three mills, including one in Madison County. He shut down the old Van Winkle mill just as the timber was becoming depleted.

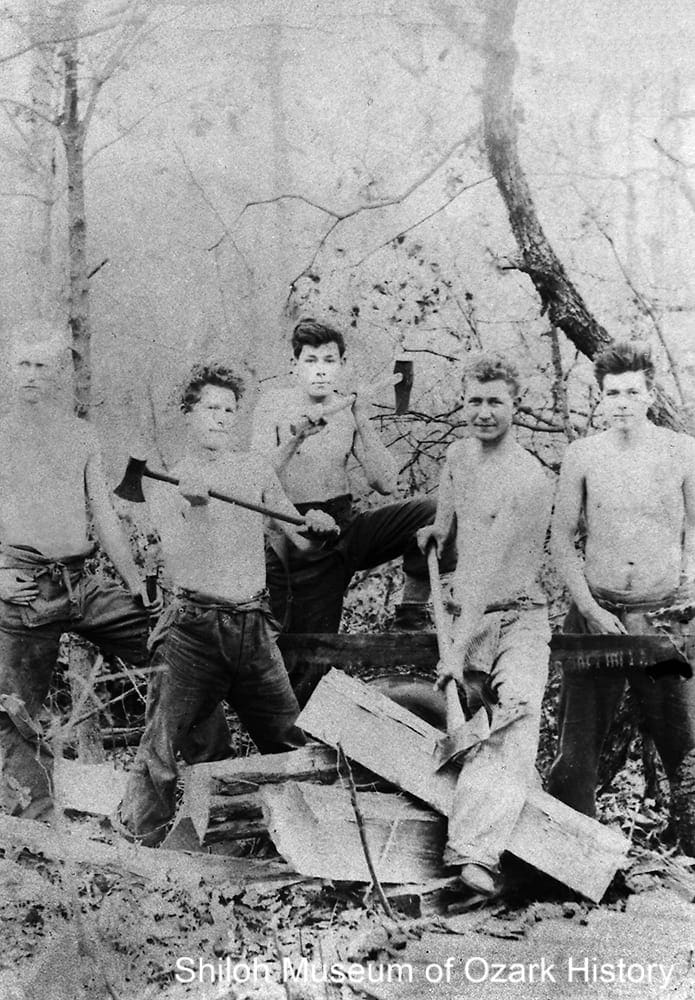

Ties, Staves, and Wagon Bows

Hacking ties, possibly the Combs area (Madison County), mid 1910s. L. A. “Andrew” Nelson, center. To the left a scored log is being hacked into shape. On the right are finished railroad ties. Gov. Orval E. Faubus Collection (S-88-144-29)

Hacking ties provided a welcome source of income to many, but the work was strenuous and dangerous and required much skill. Hackers used a two-man crosscut saw, a broadax, a double-bit ax, and other tools to cut down trees and fashion 300-pound crossties. First the log was placed on two smaller logs to raise it up off the ground. The hacker used a broadax to notch (or score) the length of the log, using the shallow cuts as a guide to “slab off” (chop) large flakes of wood called “chinks” or “juggle chips.” As the round log was shaped into a square tie, the rising pile of soft woodchips minimized damage to the ax as it was swung close to the rocky ground.

Finished ties were dragged out of the forest by mules or placed on mule-drawn wagons. The ties were hauled miles over rough terrain to bring them to a tie buyer, either an independent company or a railroad agent. A good hacker might make from six to twelve ties a day. In the 1930s some ties sold for 35 cents each, as long as they were straight, the proper dimension, and free of rot and knotholes. Some hackers tried to disguise a knothole with a plug of wood and a bit of dirt.

Ties were always in demand as railroads pushed westward. It took about 3,000 crossties to complete a mile of track. In 1900 the average tie lasted four to six years, so replacements were needed frequently. Later on, coal-tar creosote was used as a preservative, adding a few more years to a tie’s lifespan.

“[The Hobart-Lee Tie Company] owned a lot of land in and around Pettigrew, and it was common practice for people to cut trees on Hobart-Lee land, make ties, and then sell the ties [to the company]. They were ties made from trees Hobart-Lee owned to begin with, but the company never objected so long as they got their ties.”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

Stave bolt cutters, Pettigrew area, mid 1910s. Hubert Walker, second from left. The men hold (from left) a steel wedge, a cutting ax, a splitting maul, a double-bit ax, and one end of a crosscut saw. Doris Bryant Denzer and Vaughn Denzer Collection (S-2007-32-3)

Stave bolts are the blanks used for making barrel staves. Barrels were used for storing and shipping fruit, alcohol, agricultural lime, and other products. After a tree was sawn down, it was cut into pieces and split lengthwise into six-inch, curved, wedge-shaped chunks (and sometimes further split into two-inch thick slabs). The wood was stacked loosely and air-dried before being fed into a drum saw fitted with curved knives. The saw trimmed off the top and bottom of the bolt, putting a curve into the stave.

In the early 1900s there was a big stave mill at Mill Camp on Beckham Creek (Newton County). The timber cutters, bolt makers, and teamsters who drove the wagons lived in the “sleep shack,” two large tents joined together. Nearby tents housed families and other workers such as the blacksmith who put shoes on the work animals and maintained the metal parts of the machines and wagons.

Hiram Norton was the mill foreman. His wife Mattie worked as a stave catcher. She’d stand in a pit under the drum saw and catch the finished staves before stacking them on a table for them to be edged (finished). She also helped feed the mill hands. When the whistle blew mid-morning, the mill shut down and the blades were sharpened. That’s when Mattie turned her attention to the biscuits, gravy, and potatoes needed for the two o’clock dinner.

“For the timber cutters and bolt makers and the haulers, Mama [Mattie Norton] would pack their lunches and they would take it with them to the woods. They would have to be real careful where they put their lunch pail. The ants would get in their lunches.”

Ruby Norton Watson

Newton County Times, October 21, 1993

Wagon bow yard at Noah Johnson’s sawmill, Drakes Creek (Madison County), 1908. Richland Handle Company Collection (S-84-166-39)

Much labor went into making wagon bows, arched pieces of wood attached to a wagon bed and covered with a canvas “bonnet” to shelter the wagon’s contents. After the wood was cut into strips, five strips were bundled and tied with tar string to hold them together. The bundle was placed into a big wood steam vat and heated. Once the wood was flexible it was quickly placed on an arched form, bent, secured, and left to dry so the bows would keep their shape.

In its heyday, Noah Johnson’s sawmill made about 40,000 wagon bows a year, most of which were used on wagons in the Texas cotton fields and for sheltering grazing sheep in Montana. The workers also made singletrees (a bar used to help an animal better pull a wagon) and neck yokes for harnessing a team of oxen. In the 1850s Johnson had a lathe brought by oxcart from Springfield, Missouri, for use in turning square stock into round wagon-wheel spokes, singletrees, and neck yokes. The machine was still in use by the company 150 years later.

End of an Era

Burton C. Hull in his blacksmith shop at the B. C. Hull Lumber Company, Eureka Springs (Carroll County), 1967. Tim Garrison Collection (S-2012-76-48)

In 1909 over two billion board feet of lumber were cut in Arkansas. But by the early 1930s the vast stands of old-growth and second-growth forest throughout Northwest Arkansas had been exhausted. In the rush to make money, nearly every usable tree was felled. Boomtowns dwindled, production at sawmills fell, and railroad service on the St. Paul branch ended. The tracks and equipment were removed in 1937.

Some businesses were shuttered for a time. The barrel-stave industry fell victim to Prohibition, when liquor sales were illegal. But with the passage of the Cullen-Harrison Act in 1933 allowing the legal sale of beer, loggers and sawmills in Madison County were back in business. In February 1933 one mill reported an order for three million staves for beer kegs, ranging in price from nine to eleven cents each. In Kingston, D. C. Combs logged a tree which was turned into 1,145 staves. He made $38.50. The demand for staves helped some folks weather the Great Depression.

Some lumbermen did their best to adjust to the times and made a go of it. Burton C. Hull (see photo) of Eureka Springs began milling wood in the 1910s and supplied lumber for many of the town’s buildings, including Quigley Castle. When he lost part of his arm in a sawmill accident in the 1930s, he made his own prosthetic device with a metal hook on the end. Hull continued milling until about 1970.

End of an Era

Burton C. Hull in his blacksmith shop at the B. C. Hull Lumber Company, Eureka Springs (Carroll County), 1967. Tim Garrison Collection (S-2012-76-48)

In 1909 over two billion board feet of lumber were cut in Arkansas. But by the early 1930s the vast stands of old-growth and second-growth forest throughout Northwest Arkansas had been exhausted. In the rush to make money, nearly every usable tree was felled. Boomtowns dwindled, production at sawmills fell, and railroad service on the St. Paul branch ended. The tracks and equipment were removed in 1937.

Some businesses were shuttered for a time. The barrel-stave industry fell victim to Prohibition, when liquor sales were illegal. But with the passage of the Cullen-Harrison Act in 1933 allowing the legal sale of beer, loggers and sawmills in Madison County were back in business. In February 1933 one mill reported an order for three million staves for beer kegs, ranging in price from nine to eleven cents each. In Kingston, D. C. Combs logged a tree which was turned into 1,145 staves. He made $38.50. The demand for staves helped some folks weather the Great Depression.

Some lumbermen did their best to adjust to the times and made a go of it. Burton C. Hull (see photo) of Eureka Springs began milling wood in the 1910s and supplied lumber for many of the town’s buildings, including Quigley Castle. When he lost part of his arm in a sawmill accident in the 1930s, he made his own prosthetic device with a metal hook on the end. Hull continued milling until about 1970.

Manufacturing New Products

Anderson Lumber Company, Pettigrew area (Madison County), 1900s–1910s. The mill equipment was housed in the sheds in back. The yard is full of railroad ties and boards set out to air-dry. Joy Anderson Russell Collection (S-99-1-182)

Although the heyday of the lumber industry was over by the early 1930s, logging continued at a slower pace. In 1953 the lumber industry in and around Harrison had a combined payroll of over $2 million. Men were employed in cutting and milling logs and, increasingly, turning wood into finished products such as gunstocks and furniture.

“[Darius Quigley] was always known for his exact measures and could figure the laden [amount] of lumber quicker than many men around. He had little formal education and was self taught. He often remarked: ‘No one had to stay dumb if they weren’t lazy.’”

Evelyn Johnson

Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Spring 1979

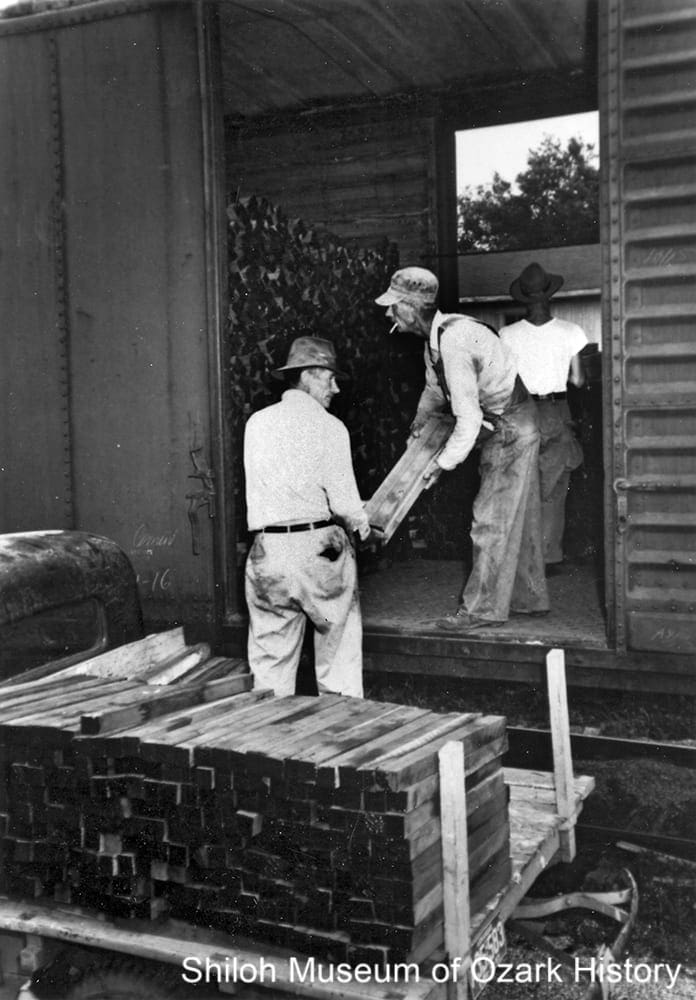

Loading walnut gunstock blanks into a railroad car at the Carl Erwin sawmill, Harrison, about 1950. From left: Ben Walker, unidentified, and Carl Browne Erwin. Steve Erwin Collection (S-97-144-34)

Manufacturing products closer to home—rather than shipping out unfinished or semi-finished wood—increased employment directly (at the mills and factories) and indirectly (workers spent their paycheck in the community). The lack of extensive timberlands didn’t matter. Increased transportation opportunities, such as additional railroad lines and paved highways, made it easier to ship products.

“If you are a young man and want to take out insurance and have no premiums to pay, plant 20 acres of walnut trees. That is the opinion of a timber gang here [at Lead Hill] moving walnut logs from this section of Boone County. . . . Any young man between 15 and 20, who will plant 20 acres of walnut trees, figuring 16 trees to the acre, can cash in for $10,000 at 60 years of age at the price being paid now. In from 40 to 45 years this price will more than double, perhaps triple.”

Arkansas Gazette, December 17, 1925

I. C. Sutton Handle Factory’s display of shovel and hoe handles and baseball bats, Harrison (Boone County), 1950s. Harry Sutton Collection (S-89-140-55)

When I. C. Sutton moved to Newton County he ran a general store in Lurton. He couldn’t help but notice the surrounding trees and thought there must be a way to make money from them. In the 1920s he began making rustic chairs with hickory-bark seats. Sutton bought a small handle mill from a neighbor in 1929. Soon the whole family became involved in making ash and hickory tool handles and baseball bats. By 1949 the company, with its 30 or so workers, was netting about $160,000 a year. The business moved to Harrison in 1952 and shipped products throughout the United States for a number of years.

“The amazing thing about this business is that Arkansas is a leader in manufacturing [implement handles], part of which go out all over the world.”

Neil Johnson

Springdale News, August 30, 1966

Environmental Issues

Probably the Van Winkle sawmill, War Eagle area (Benton County), 1880s–1890s. In the center foreground sits a wagon with its bed removed to make it easier to load logs and decrease the wagon’s weight. Behind are wagons taking logs to the mill. A mountain of boards (about 22 feet tall!) dry to the right. The once-forested hillside boasts a few spindly trees. Dr. William C. Donovan Collection (S-91-6-9)

As the early loggers found out, not only did overharvesting wipe out the trees needed to maintain the industry, it also led to environmental problems such as soil runoff, air and water pollution, and loss of habitat. Today logging can be a hot-button issue, pitting environmental ideals against employment opportunities.

When Mountain Pine Timber began logging near Jasper (Newton County) in the late 1980s, environmental groups called it clear-cutting and feared that it would “irreparably damage” the environment and impact residents and the tourists who came for the natural beauty of the Buffalo River. Some residents didn’t want the logging to continue while others felt that if it didn’t, their livelihoods would be taken away. Others wanted to be sure that landowners’ property rights were upheld.

Environmental Issues

Probably the Van Winkle sawmill, War Eagle area (Benton County), 1880s–1890s. In the center foreground sits a wagon with its bed removed to make it easier to load logs and decrease the wagon’s weight. Behind are wagons taking logs to the mill. A mountain of boards (about 22 feet tall!) dry to the right. The once-forested hillside boasts a few spindly trees. Dr. William C. Donovan Collection (S-91-6-9)

As the early loggers found out, not only did overharvesting wipe out the trees needed to maintain the industry, it also led to environmental problems such as soil runoff, air and water pollution, and loss of habitat. Today logging can be a hot-button issue, pitting environmental ideals against employment opportunities.

When Mountain Pine Timber began logging near Jasper (Newton County) in the late 1980s, environmental groups called it clear-cutting and feared that it would “irreparably damage” the environment and impact residents and the tourists who came for the natural beauty of the Buffalo River. Some residents didn’t want the logging to continue while others felt that if it didn’t, their livelihoods would be taken away. Others wanted to be sure that landowners’ property rights were upheld.

Lumber Industry Today

Logging has continued, but on a much smaller scale. The Martin family of Pettigrew (Madison County) began logging just as the timber was playing out. But because they were a small-scale operation, they didn’t need an inexhaustible number of trees. They were able to log selectively, leaving the smaller specimens for the next generation to harvest. By 1992, when Wayne Martin finally quit the family business, he had likely logged the same hills as his father and grandfather.

Today in Madison County, Willhite Forest Products in St. Paul makes railroad ties, flooring, and slats for wood pallets. In Wesley the Richland Handle Company makes handles for tools and implements such as rakes, shovels, hammers, and picks. J. R. Banks Lumber in Marble (Newton County) has made railroad ties since the 1960s. They’ve also begun producing lumber and pre-cut pallet stock. These are just a few of the companies that continue the long tradition of lumbering in Northwest Arkansas.

“Like my dad, I too was in the woods by the time I was fifteen, but not on a daily basis. I quit in 1992, so I worked in the timber about forty years. . . . The roads were good enough, and the vehicles were good enough. I had a friend who harped at me constantly, saying that I was going to get killed out there. One day I got tired of it. I said, ‘If I do, I’ll die happy.’”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

Lumber Industry Today

Logging has continued, but on a much smaller scale. The Martin family of Pettigrew (Madison County) began logging just as the timber was playing out. But because they were a small-scale operation, they didn’t need an inexhaustible number of trees. They were able to log selectively, leaving the smaller specimens for the next generation to harvest. By 1992, when Wayne Martin finally quit the family business, he had likely logged the same hills as his father and grandfather.

Today in Madison County, Willhite Forest Products in St. Paul makes railroad ties, flooring, and slats for wood pallets. In Wesley the Richland Handle Company makes handles for tools and implements such as rakes, shovels, hammers, and picks. J. R. Banks Lumber in Marble (Newton County) has made railroad ties since the 1960s. They’ve also begun producing lumber and pre-cut pallet stock. These are just a few of the companies that continue the long tradition of lumbering in Northwest Arkansas.

“Like my dad, I too was in the woods by the time I was fifteen, but not on a daily basis. I quit in 1992, so I worked in the timber about forty years. . . . The roads were good enough, and the vehicles were good enough. I had a friend who harped at me constantly, saying that I was going to get killed out there. One day I got tired of it. I said, ‘If I do, I’ll die happy.’”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

Credits

Barnickol, Lynn. “Sleepers Through Time.” Forest History Today, 1997.

“Blackburns Prominent in County’s Heritage.” Rogers Daily News, February 29, 1976.

Blair, William M. “New Grazing Range is ‘Found’ in Ozarks.” New York Times, September 11, 1953.

Bland, Gaye H. “Land of Opportunity: The Riches of Lumbering in Benton County.” Ozark View, Vol. 1, No. 4 (August 1993).

Brotherton, Velda. “The Crop of the Ozarks.” White River Valley News, September 7, 2000.

Campbell, Denele Pitts. “Fayette Junction: Hub of Washington County’s 1885-1935 Timber Boom.” Flashback, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Winter 2005).

Campbell, William S. One Hundred Years of Fayetteville 1828-1928. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1977.

Cox, Tim. “JR Banks Lumber Launches Scragg Mill to Make Pre-Cut Pallet Stock.” Pallet Enterprise, September 1, 2009 (accessed June 13, 2019).

Cutter, Bruce. Circular Sawmill Alignment and Maintenance. University of Missouri Extension Service, 1980.

Deane, Ernie. “Old Industry Thrives.” Springdale News, March 21,1984.

Dillard, Tom W. “Cedar Harvesting for Pencils was Rugged Work.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 14, 2007.

Doyle, Fred. “Logging on Winn Creek in 1920.” Washington County Observer, March 29, 1984.

“Drag Saws.” Mendocino Coast Model Railroad and Historical Society, accessed June 2019.

“Dutton Tie Yard.” Madison County Record, March 20, 2008.

Easley, Barbara P., and Verla P. McAnelley. Obituaries of Benton County, Arkansas. Vol. 3, 1905–1909. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1995.

Easley, Barbara P., and Verla P. McAnelley. Obituaries of Benton County, Arkansas. Vol. 5, 1914–1919. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1995.

Edmisten, Bob. “Johnsons Pioneered Saw Milling Industry.” Springdale News, August 30, 1966.

Edmisten, Bob. “St. Paul Flourishes in History of Timber and Railroad.” Springdale News, December 6, 1966.

Edmisten, Robert. “Family ‘Handles’ Mill: Fifth Generation Operates Historic Business.” Morning News, October 20, 2003.

“Ernie Deane’s Arkansas Photographs.” Old State House Museum (accessed May 2012).

“Frisco Railroad’s St. Paul Branch Line Ends 50 Years Run.” Fayetteville Daily Democrat, July 31, 1937.

“Future of Charcoal Plant to be Discussed May 7.” Madison County Record, April 25, 1985.

Garrison, Tim. Conversation about sawmills. Springdale, Arkansas. April 11, 2012.

Haight, Christine. “Sutton Handle Factory: The Beginnings.” Newton County Times, September 25, 1997.

“J. A. C. Blackburn.” Rogers Historical Museum, accessed June 13, 2019.

Johnson, Evelyn. “Early Sawmills of Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXIV, No. 1 (Spring 1979).

Jones, Raymond L. “Remembrance of Things Past: Cross Ties.” Washington County Observer, December 12, 1981.

Jones, Raymond L. “Remembrance of Things Past: Stave Bolt Mills.” Washington County Observer, January 14, 1982.

Lackey, Daniel Boone. “Red Cedar Cutting.” Newton County Homestead, Vol. 2, No. 1 (April 1960).

Lair, Jim. “The Hanbys: ‘Lumber Kings of Carroll County.’” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (Summer 1985).

Lister, Addie Lee. “Remembering Fayette Junction.” Flashback, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Winter 2006).

“Logging of Large Tract in County Prompts Discussion.” Newton County Times, October 26,1989.

Martin, Orville and Wayne. Interview about tie hacking. Springdale, Arkansas. August 18, 1987.

Martin, Wayne. Conversation about stave bolts. Springdale, Arkansas. June 2007.

Martin, Wayne. Pettigrew, Arkansas: Hardwood Capital of the World. Springdale, AR: Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, 2010.

Massey, Richard. “Mill Owner Rebuilding Days After Fire.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 13, 2009.

McNeil, W. K., and William M. Clements, eds. An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press,1992.

Mesavage, Clement. “Timber—One of Nation’s Greatest Natural Resources.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 2, No. 10 (May 1954).

Neal, Joseph C. “The Oak of the Ozarks.” Grapevine, Vol. XIX, No. 22 (June 15, 1988).

Nehring, Radine Trees. “Treating the Forest Kindly with Pony-Style Logging.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 2, No. 2 (May/June 1992).

“Other Days from the Gazette Files: 50 Years Ago (Lead Hill, December 17, 1925),” Arkansas Gazette, December 1975.

Rafferty, Milton. “The Ozark Forest: Its Exploitation and Restoration.” OzarksWatch, Vol. VI, Nos. 1 and 2 (Summer and Fall 1992).

Rose, F. P. “The Springfield Wagon Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. X, No. 1 (Spring 1951).

Rose, F. P. “Van Winkle Mill Did Yeoman Duty: Pioneer Maker of Lumber in Western Ozarks.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 2, No. 5 (November 1953).

Sherrer, Dwayne. “Sawmilling Process in the Ozarks.” Bittersweet, Vol. IX, No. 3 (Spring 1982).

Smiley, James R. Conversation about sawmills. Gentry, Arkansas. April 22, 2012.

“Stave Market for Beer Barrels.” Madison County Musings, Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (Fall 1999).

Stout, Chuck. Conversation about sawmills. Pettigrew, Arkansas. April 14, 2012.

“Sutton Handle Factory.” RootsWeb, accessed June 2019.

Thompson, Paula. “It Was, ‘One Vast, Trackless Wilderness.’” Arkansas Magazine, March 10, 1985.

“Tricksters Discourage Black Settlers.” [Rogers Daily News?], June 29, 1976. Shiloh Museum research files.

Watson, Ruby. “Hickory Grove.” Newton County Times, October 21, 1993.

Westphal, June, and Catharine Osterhage. A Fame Not Easily Forgotten: An Autobiography of Eureka Springs. Eureka Springs, AR: Boian Books, LLC, 2010.

Winn, Robert G. “Loggers Were Flush and Timber was King.” Northwest Arkansas Times, March 10, 1986.

Winn, Robert G. “Recollections: Timber.” Washington County Observer, March 25, 1982.