Limelight

Online ExhibitWhat is Lime?

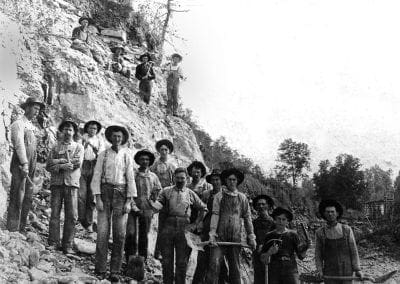

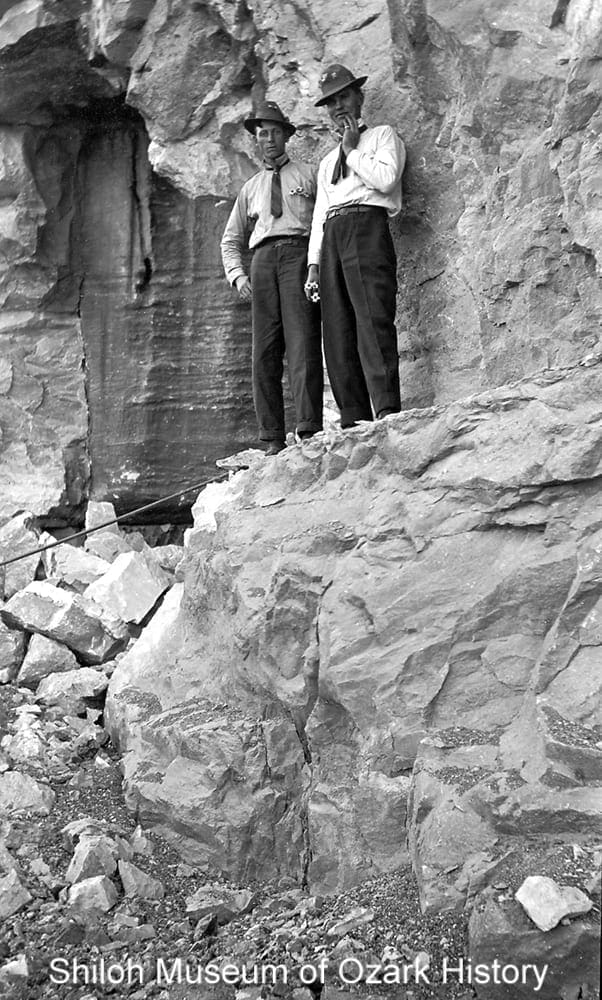

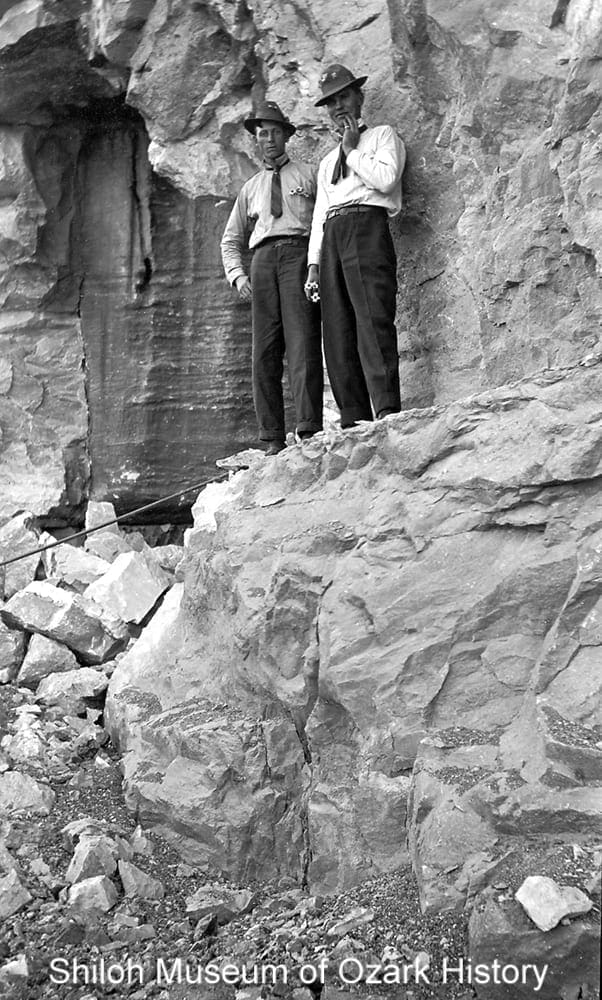

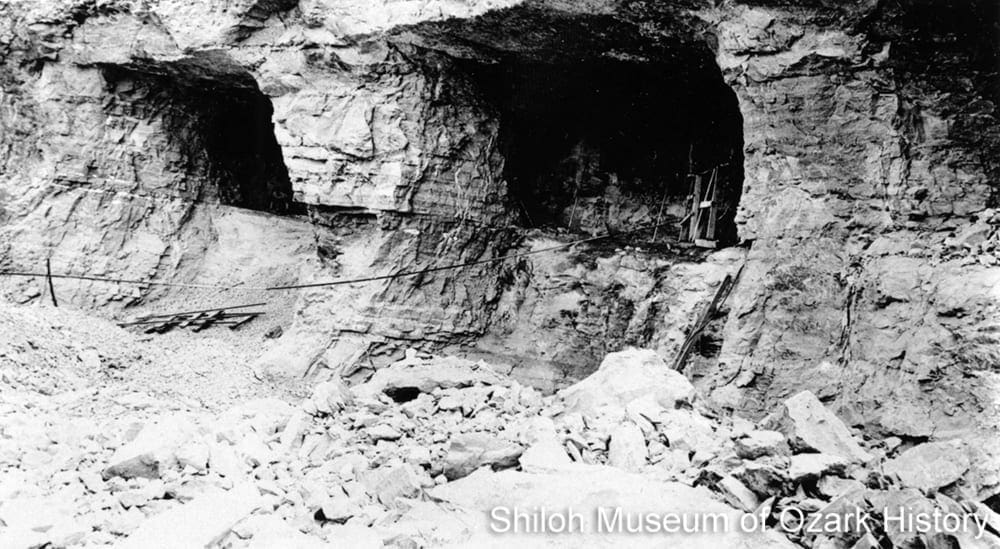

Sightseers at the lime quarry, Johnson, about 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-456)

Limestone (calcium carbonate) is a sedimentary (layered) rock created from the mineralized skeletons and shells of marine animals. One layer of limestone, known as the Boone formation, was deposited over 300 million years ago when a shallow ocean covered what is now Northwest Arkansas. The Boone formation is extensive and composed of high-quality limestone and chert.

At the turn of the 20th century, local lime companies quarried limestone and burned it in a kiln (a big fire pit) to produce a product known as quicklime. The cooked, powdery substance is unstable and must be kept dry, or it can turn back into limestone. By 1923, the Ozark White Lime Company was able to make hydrated lime (slaked lime) by carefully adding water to quicklime. Hydrated lime is more stable and safe to handle than quicklime.

Quicklime was used in the manufacture of mortar, plaster, and cement. In March 1908 Ozark White Lime took on a number of new workers “since the rush of spring building has caused such a demand for . . . [its] lime which is being shipped to a number of states of the great Mississippi valley.” Farmers used both quicklime and hydrated lime as a soil amendment and fertilizer. In the 1930s lime was used to make an insecticide for use on cotton crops.

“The lime kilns . . . are doing a big business again and several cars of the celebrated product of the Clear Creek bluffs go out daily to the markets of the northwest. Folks would be surprised to know the amount of lime shipped from Johnson in the course of a year, for there are eight large kilns located here now.”

Marion Mason

Springdale News, June 1, 1906

Sightseers at the lime quarry, Johnson, about 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-456)

What is Lime?

Limestone (calcium carbonate) is a sedimentary (layered) rock created from the mineralized skeletons and shells of marine animals. One layer of limestone, known as the Boone formation, was deposited over 300 million years ago when a shallow ocean covered what is now Northwest Arkansas. The Boone formation is extensive and composed of high-quality limestone and chert.

At the turn of the 20th century, local lime companies quarried limestone and burned it in a kiln (a big fire pit) to produce a product known as quicklime. The cooked, powdery substance is unstable and must be kept dry, or it can turn back into limestone. By 1923, the Ozark White Lime Company was able to make hydrated lime (slaked lime) by carefully adding water to quicklime. Hydrated lime is more stable and safe to handle than quicklime.

Quicklime was used in the manufacture of mortar, plaster, and cement. In March 1908 Ozark White Lime took on a number of new workers “since the rush of spring building has caused such a demand for . . . [its] lime which is being shipped to a number of states of the great Mississippi valley.” Farmers used both quicklime and hydrated lime as a soil amendment and fertilizer. In the 1930s lime was used to make an insecticide for use on cotton crops.

“The lime kilns . . . are doing a big business again and several cars of the celebrated product of the Clear Creek bluffs go out daily to the markets of the northwest. Folks would be surprised to know the amount of lime shipped from Johnson in the course of a year, for there are eight large kilns located here now.”

Marion Mason

Springdale News, June 1, 1906

The Business of Lime

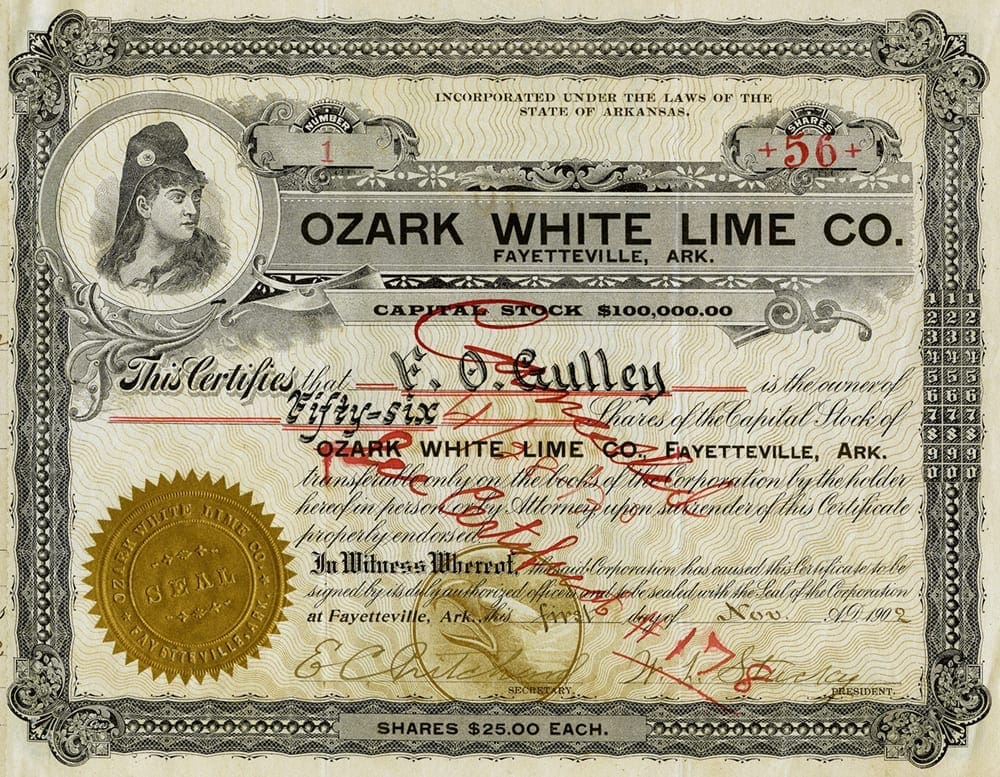

Ozark White Lime Company stock certificate #1, made out to Frank O. Gulley, Ozark White Lime vice-president, November 1, 1902.

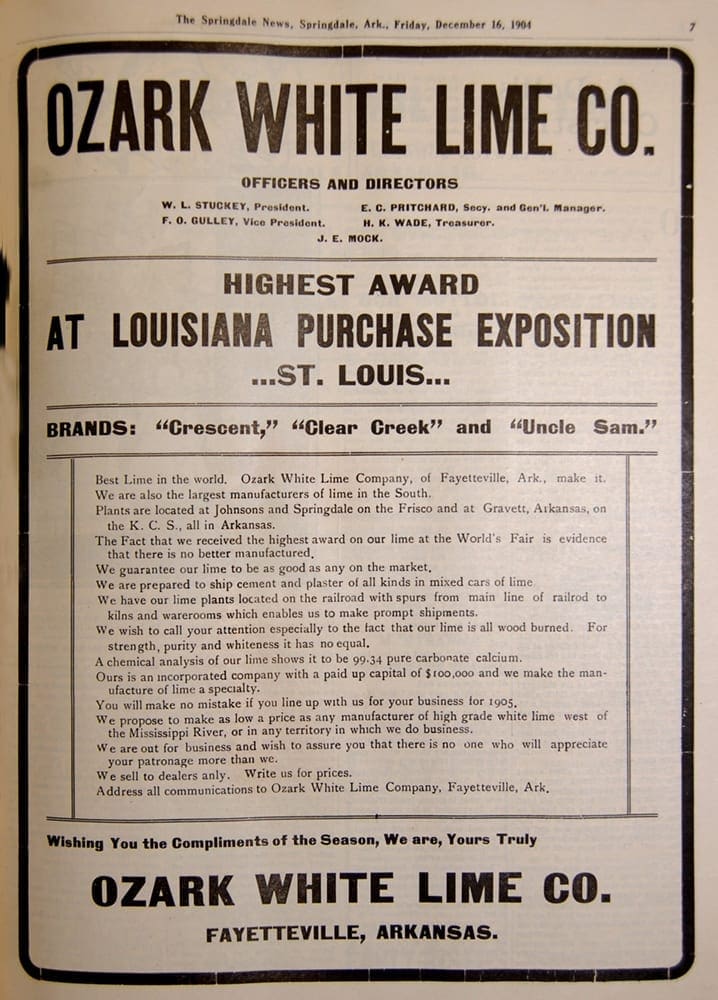

Lime is an inexpensive product. Its weight and bulk made long-distance transportation by wagon unprofitable. Because railroads offered a cost-effective way to move mountains of lime, generally only those limestone deposits located near rail lines were exploited. Over twenty lime companies are known to have been in operation in Northwest Arkansas in the late 1800s and early 1900s, primarily in Benton and Washington counties. The two largest were the Rogers White Lime Company and the Ozark White Lime Company.

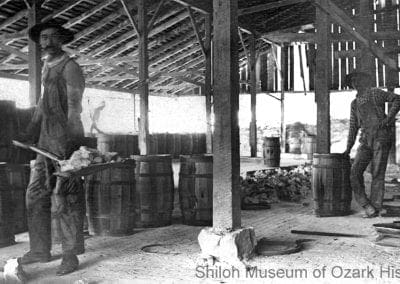

Rogers White Lime—Begun in 1893, fifty men worked the quarry and kiln at Diamond Springs, east of Rogers. Businessman (and later company president) Fleming Fontaine Freeman bought an interest in the company in 1900 and began making improvements, such as purchasing equipment to build shipping barrels in-house. The Diamond Springs plant closed in 1902 when the Cross Hollow plant came online. Cross Hollow had three kilns and a 1,000-feet-long rail siding along the Monte Ne Railway, allowing it to connect to other shipping points via a Rogers-area railroad line. The company marketed its Lily White Lime brand as 99.4% pure. A steam engine was installed in 1905 to operate the heavy cables needed to pull rock-filled tram cars up a tramway to the tops of the kilns. In 1908 the company shipped out 75,000 barrels of lime in 600 rail cars, valued at $55,000; that year the entire output for eastern Benton County was 125,000 barrels. A steam-powered lime crusher was added in 1913 and two years later, two kilns were erected east of the White River, possibly because the lime was running out at Cross Hollow. Freeman was replaced as president in 1915 after a series of financial blows. The company was on shaky ground as the parent company of the Monte Ne Railway was about to abandon the line. Rogers White Lime entered bankruptcy in 1918.

Ozark White Lime—The Crescent White Lime Works was founded by John W. Carter in Johnson around 1891, along a massive limestone bluff flanking Clear Creek. In 1897 Fayetteville investors purchased Carter’s operation for $2,500, at a time when the kiln was producing 100 barrels per day. With W. L. Stuckey as president and Frank O. Gulley as vice-president, the company incorporated two years later with a capital stock of $10,000. They changed the name to Ozark White Lime in 1902 and later purchased a second lime plant nearby. By the 1920s the company produced 50,000 barrels annually. In 1923 the company installed an electric hydrating plant, the first in the state. Ozark White Lime doubled its output, processing 40 tons of lime in a ten-hour period. They sold “Clear Creek” quicklime and “Sunshine” hydrated lime. About 100 men worked at the quarries and kilns throughout the year, more if both plants were operating. Cordwood came from Oklahoma, where Gulley owned timberland; the company switched to cheaper natural gas in the 1930s. The plant made 50,000 barrels a year using shipped-in barrel parts. In 1940 the company had forty to fifty workers and sold lime in twelve states. About 50% of its output went to the chemical trade for use in paper mills, city water plants, and oil companies. By the mid 1940s the lime deposits were depleted and the business closed.

“The new electric hydrating plant [at Ozark White Lime] includes a crusher for powdering burned lime, a separator for eliminating all impurities, a five-foot fan or blower, an 80-ton storage bin for ground lime, and another of same capacity for storage of finished hydrated lime, a patent bagging machine that sacks all lime and automatically seals it ready for shipping, three elevators 40 feet high, [and] a 50-foot dust stack topping the plant, giving it a total height of 85 feet. Two men will be employed for sacking . . .”

Fayetteville Daily Democrat, October 13, 1923

The Business of Lime

Ozark White Lime Company stock certificate #1, made out to Frank O. Gulley Ozark White Lime vice-president, November 1, 1902.

Lime is an inexpensive product. Its weight and bulk made long-distance transportation by wagon unprofitable. Because railroads offered a cost-effective way to move mountains of lime, generally only those limestone deposits located near rail lines were exploited. Over twenty lime companies are known to have been in operation in Northwest Arkansas in the late 1800s and early 1900s, primarily in Benton and Washington counties. The two largest were the Rogers White Lime Company and the Ozark White Lime Company.

Rogers White Lime—Begun in 1893, fifty men worked the quarry and kiln at Diamond Springs, east of Rogers. Businessman (and later company president) Fleming Fontaine Freeman bought an interest in the company in 1900 and began making improvements, such as purchasing equipment to build shipping barrels in-house. The Diamond Springs plant closed in 1902 when the Cross Hollow plant came online. Cross Hollow had three kilns and a 1,000-feet-long rail siding along the Monte Ne Railway, allowing it to connect to other shipping points via a Rogers-area railroad line. The company marketed its Lily White Lime brand as 99.4% pure. A steam engine was installed in 1905 to operate the heavy cables needed to pull rock-filled tram cars up a tramway to the tops of the kilns. In 1908 the company shipped out 75,000 barrels of lime in 600 rail cars, valued at $55,000; that year the entire output for eastern Benton County was 125,000 barrels. A steam-powered lime crusher was added in 1913 and two years later, two kilns were erected east of the White River, possibly because the lime was running out at Cross Hollow. Freeman was replaced as president in 1915 after a series of financial blows. The company was on shaky ground as the parent company of the Monte Ne Railway was about to abandon the line. Rogers White Lime entered bankruptcy in 1918.

Ozark White Lime—The Crescent White Lime Works was founded by John W. Carter in Johnson around 1891, along a massive limestone bluff flanking Clear Creek. In 1897 Fayetteville investors purchased Carter’s operation for $2,500, at a time when the kiln was producing 100 barrels per day. With W. L. Stuckey as president and Frank O. Gulley as vice-president, the company incorporated two years later with a capital stock of $10,000. They changed the name to Ozark White Lime in 1902 and later purchased a second lime plant nearby. By the 1920s the company produced 50,000 barrels annually. In 1923 the company installed an electric hydrating plant, the first in the state. Ozark White Lime doubled its output, processing 40 tons of lime in a ten-hour period. They sold “Clear Creek” quicklime and “Sunshine” hydrated lime. About 100 men worked at the quarries and kilns throughout the year, more if both plants were operating. Cordwood came from Oklahoma, where Gulley owned timberland; the company switched to cheaper natural gas in the 1930s. The plant made 50,000 barrels a year using shipped-in barrel parts. In 1940 the company had forty to fifty workers and sold lime in twelve states. About 50% of its output went to the chemical trade for use in paper mills, city water plants, and oil companies. By the mid 1940s the lime deposits were depleted and the business closed.

“The new electric hydrating plant [at Ozark White Lime] includes a crusher for powdering burned lime, a separator for eliminating all impurities, a five-foot fan or blower, an 80-ton storage bin for ground lime, and another of same capacity for storage of finished hydrated lime, a patent bagging machine that sacks all lime and automatically seals it ready for shipping, three elevators 40 feet high, [and] a 50-foot dust stack topping the plant, giving it a total height of 85 feet. Two men will be employed for sacking . . .”

Fayetteville Daily Democrat, October 13, 1923

The Workers

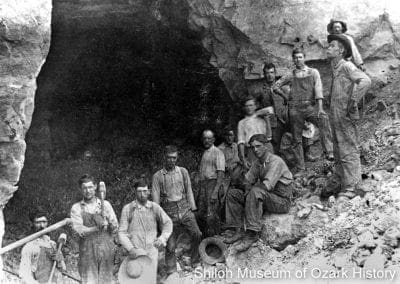

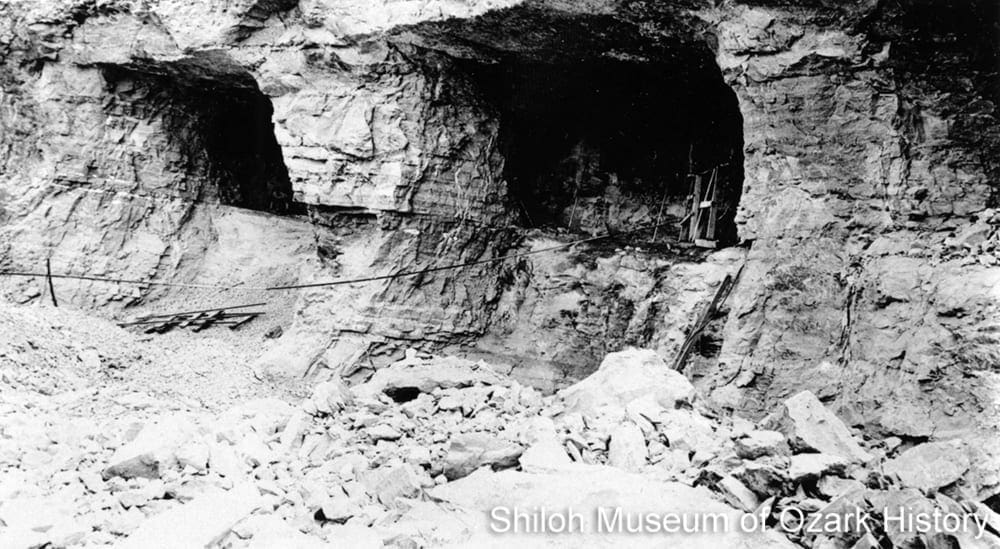

A lime mine in Johnson (Washington County), about 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2015-20-5)

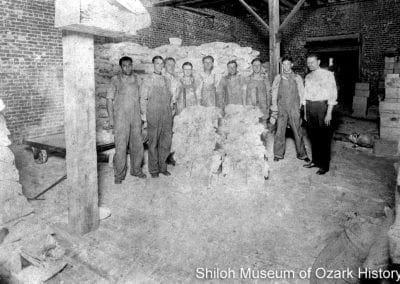

Men were needed to quarry the rock, move it to the kilns, cook the lime, crush it, and shovel it into barrels for shipment. Coopers made barrels, blacksmiths shoed horses and made or repaired equipment, and timber cutters provided cordwood for firing kilns and wood for making barrels. Local farmers earned extra money by selling cordwood from newly cleared land or working at the lime plants and quarries during the winter months.

In Johnson, men worked twelve-hour shifts, one starting at noon, the other at midnight. Workers earned fifteen to twenty cents an hour. Many worked six or seven days a week. Because of their relative isolation and the long working days, the larger lime companies built employee housing and operated company stores. At Cross Hollow, workers could rent a house for $1.25 to $1.50 a month. At the Johnson kilns, there were twenty to thirty two-room houses in “Lime Kiln Hollow.” In 1936, J. D. Cordell worked ten-hour days, fifity-five hours a week, for $5.50. Rent was $3.00 a month and a week’s worth of groceries cost $3.00.

A Dangerous Profession

Rockslides, accidents, and burning lime made for hazardous work. In 1904 Bob Wright fell thirty-five feet from a scaffold at a Johnson quarry. The fall fractured his arm and leg, cut off his lower lip, and caused internal injuries. The doctor gave him “little hope of recovery.” Sometime around 1906, a hole was drilled into the rock face at Ozark White Lime and an explosive charge placed inside. It failed to detonate. The next day the foreman held the drill in the same hole as a seventeen-year-old pounded on it with a hammer. After a few blows the drill hit the explosive, killing the foreman and seriously injuring the youth.

Quicklime was dangerous. It irritated a worker’s skin, sometimes causing burns. Former lime-kiln worker Al Luper once recalled, “It would take the hide right off you.” When mixed with water, quicklime creates a violent chemical reaction. Luper recalled seeing patches of lime burning in Clear Creek, on a day the river had overflowed its banks and swept through the lime plant. The creek often played havoc with the kilns. In 1906, 200 barrels of lime were destroyed at the Crystal kiln. The kiln shed nearly caught on fire from the burning lime.

“Neal Alvis was accidentally hurt while at work at the [Crescent] lime kiln last Wednesday. A hammer flew off the handle and struck him on the head inflicting what may yet prove to be a fatal fracture of the skull.”

Springdale News, September 6, 1895

The Workers

A lime mine in Johnson (Washington County), about 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2015-20-5)

Men were needed to quarry the rock, move it to the kilns, cook the lime, crush it, and shovel it into barrels for shipment. Coopers made barrels, blacksmiths shoed horses and made or repaired equipment, and timber cutters provided cordwood for firing kilns and wood for making barrels. Local farmers earned extra money by selling cordwood from newly cleared land or working at the lime plants and quarries during the winter months.

In Johnson, men worked twelve-hour shifts, one starting at noon, the other at midnight. Workers earned fifteen to twenty cents an hour. Many worked six or seven days a week. Because of their relative isolation and the long working days, the larger lime companies built employee housing and operated company stores. At Cross Hollow, workers could rent a house for $1.25 to $1.50 a month. At the Johnson kilns, there were twenty to thirty two-room houses in “Lime Kiln Hollow.” In 1936, J. D. Cordell worked ten-hour days, fifity-five hours a week, for $5.50. Rent was $3.00 a month and a week’s worth of groceries cost $3.00.

A Dangerous Profession

Rockslides, accidents, and burning lime made for hazardous work. In 1904 Bob Wright fell thirty-five feet from a scaffold at a Johnson quarry. The fall fractured his arm and leg, cut off his lower lip, and caused internal injuries. The doctor gave him “little hope of recovery.” Sometime around 1906, a hole was drilled into the rock face at Ozark White Lime and an explosive charge placed inside. It failed to detonate. The next day the foreman held the drill in the same hole as a seventeen-year-old pounded on it with a hammer. After a few blows the drill hit the explosive, killing the foreman and seriously injuring the youth.

Quicklime was dangerous. It irritated a worker’s skin, sometimes causing burns. Former lime-kiln worker Al Luper once recalled, “It would take the hide right off you.” When mixed with water, quicklime creates a violent chemical reaction. Luper recalled seeing patches of lime burning in Clear Creek, on a day the river had overflowed its banks and swept through the lime plant. The creek often played havoc with the kilns. In 1906, 200 barrels of lime were destroyed at the Crystal kiln. The kiln shed nearly caught on fire from the burning lime.

“Neal Alvis was accidentally hurt while at work at the [Crescent] lime kiln last Wednesday. A hammer flew off the handle and struck him on the head inflicting what may yet prove to be a fatal fracture of the skull.”

Springdale News, September 6, 1895

Today's Lime

The production of quicklime and hydrated lime in Northwest Arkansas started to taper off in Johnson in the 1930s, although the plant remained in operation during World War II. In 1949 Clark and Charles McClinton leased the defunct quarry and operated a rock-crushing plant, producing gravel for road construction. Zero Mountain, Inc., turned the old lime caverns into cold-storage facilities in 1955, which are still in use today. For a time one of the abandoned caverns was the scene of many parties and fraternity initiations.

At Cross Hollow, Bill Branningham built a new plant in 1952 to process agricultural lime, operating the business into the 1960s. Although Rogers White Lime is long gone, the 1905 concrete powerhouse used to power the tram cars still stands. Today the only company in the state still producing quicklime is the Arkansas Lime Company in Batesville.

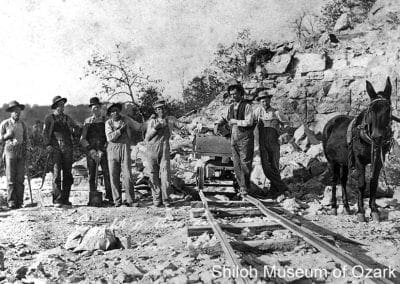

Making Lime in Johnson, Circa 1908

(1) A massive limestone bluff towered over Clear Creek, just south of present-day Johnson. First, the powder gang used dynamite to blast out large sections of rock. (2) Then miners tunneled into the side of the bluff to dig out the lime, (3) creating a cavern with giant pillars. (4) Then the miners used picks, large hammers, and shovels to break up and move the rock. In later years, steam-powered drills were used.

[The quarry is] “. . . a solid mountain of white limestone, now tunneled into until it resembles a mammoth cave. Great upright pillars of white stone, left as supports, more than 30 feet high and 20 feet across support the stone roof above and give the place the appearance of a great marble hall more than 300 feet square . . . An everlasting spring at a depth of more than 200 feet has been found here and supplies the working force with drinking water.”

Fayetteville Daily Democrat, October 13, 1923

“That wasn’t an earthquake last Friday evening, but it was one of the largest blasts ever put off at the lime quarries here [in Johnson]. The charge consisted of several hundred sticks of dynamite all fired at once by means of a battery and rock enough was displaced to furnish work . . . for quite a while. ”

Marion Mason

Springdale News, February 15, 1907

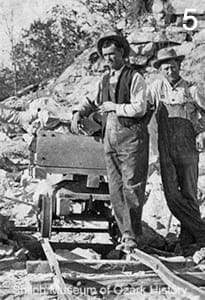

The rock was either shoveled into mule-drawn wagons and hauled to the kilns or (5) it was placed in small, wheeled tram cars and transported along a narrow-gauge rail by way of a pulley system. (6) The cars traveled along a tall wood tramway from the quarry (7) to the top of the kiln. Trees were chopped down and cut into cordwood, which was transported to the kiln by rail or (8) mule-drawn wagons.

“There are 3 kilns at [the Ozark White Lime] plant and 3 at the Crescent, up by the [railroad], both plants are owned and operated by the Ozark Lime Co. The[y] still use wood for fuel, and wood is worth 2.50 to 3- per cord now, and the local supply is short at that, so they ship in many car loads from other points.”

Marion Mason

Springdale News, January 1, 1909

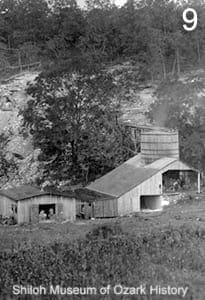

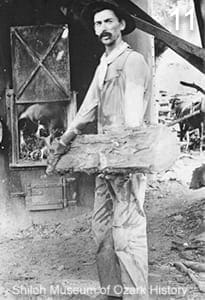

The average kiln used between 4,000 to 6,000 cords of wood each year. (9) The kiln was often part of a larger complex of buildings which housed the cooling floor, the barrel-making shed, storage for wagons and barreled lime, and perhaps a place to stable the mules. (10) The kiln was a wide, steel column, twenty feet high or more. It was lined on the inside with refractory brick, designed to withstand high temperatures. (11) The fireman was in charge of the kiln, heating it to about 2,000° Fahrenheit. He stoked the furnace with cordwood. The kiln ran twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. It was only shut down for repairs or accidents, or when there was reduced demand for lime.

The extreme temperature burned off the carbon dioxide in the limestone and transformed the rock into quicklime. As the bottom layer of rock burned down, more rock was added to the top. The lime had to be cooked just right, taking into account such factors as the rate of combustion, the quality of the fuel, and the direction and force of the wind. If the lime was undercooked or overcooked, it couldn’t be used.

(12) Wood barrels were made by skilled coopers (barrel makers) out of local materials. At some plants, the barrel parts were made elsewhere and shipped to the plant for assembly. Each barrel held about 200 pounds of lime. It needed to be solidly built and reinforced with strong bands.

“The flames that at each firing of six hours had to heat the rock to a temperature of 2200 degrees came from cords and cords of wood, 3,000 a year. Fifteen thousand dollars every year gone up in smoke in those kilns whose flaming bellies squat solidly against the rock face of the mountain they are devouring. Forests about Johnson gone . . .”

Cecil Shuford

August 17, 1928

[Ozark White Lime] “. . . had its own coopers, who manufactured barrels for storing and shipping the processed lime. Because of the demand for barrels, [Al] Luper found the cooper’s trade more lucrative than crushing rock. He sold barrels to the company for 6 cents apiece, and he also manufactured apple barrels for 7 cents apiece . . .”

Bob Edmisten

Springdale News, April 11, 1980

(13) Every five or six hours the firemen used long, metal rods to pull out about thirty to thirty-five barrels worth of quicklime from the draw pits at the bottom of the kiln. (14) The hot, glowing rocks were spread onto a brick-lined floor and allowed to cool for several hours. Then they were broken into smaller pieces using heavy hammers. (15) The lime was shoveled into barrels and (16) shipped out.

PHOTO CREDITS

All images, except for 3 and 4, were taken by Marion Mason in Johnson, circa 1908.

1. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-308)

2. Theresa Eubanks Collection (S-87-256-2)

4. Benton County History Book Collection (S-92-49-64)

5. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-2010-96-22)

6. Ann Lichlyter Davis Collection (S-2005-95-23)

7. Phillip Steele Collection (S-78-34-57)

8. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-2010-96-21)

9. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-307)

10. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-144)

11. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-295)

12. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-325)

13. Don Bailey Collection (S-2015-20-3)

14, 15. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-294)

16. Charlotte Steele Collection (S-2014-68)

Documenting the Johnson Lime Companies

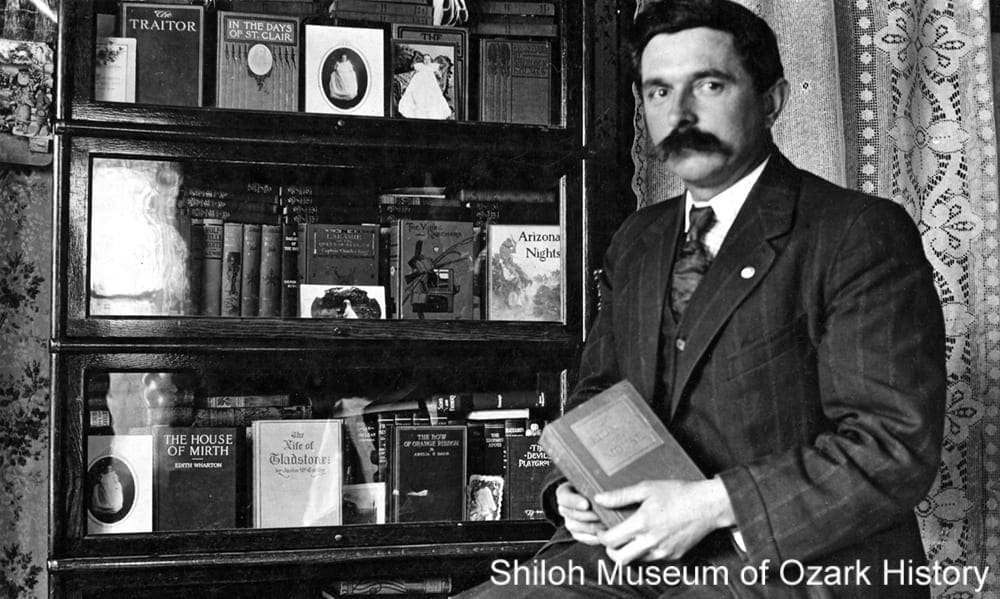

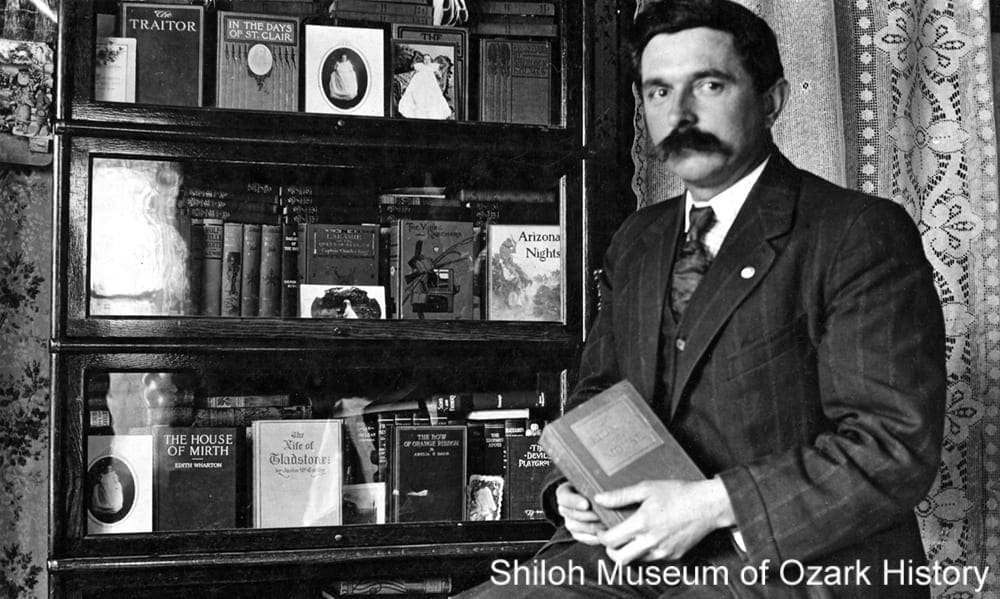

Marion Mason at the Hanks home, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-621)

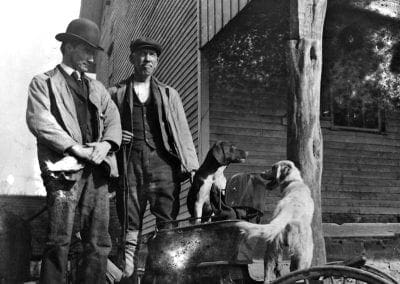

Marion DeKalb Mason (1875–1946) was the long-time Johnson correspondent for the Springdale News. Writing under the penname “Mulkeepmo,” his columns were filled with neighborhood happenings, including news about the lime kilns.

Mason was a prolific and accomplished amateur photographer, shooting images first on glass plate and later on acetate film stock. He delighted in taking photos of family, friends, scenery, and local businesses, often printing the images on postcards and giving them away or mailing them to friends.

Mason lived with his sister and brother-in-law, Maud and Nathan Hanks, and their children in the Hanks home in Johnson, just down the road from the Johnson mill and the lime companies. It’s thanks to his writings and to the many generous folks who have shared his images (including Mason’s relatives) that the Shiloh Museum is able to preserve the rich history of Johnson’s lime industry.

Documenting the Johnson Lime Companies

Marion Mason at the Hanks home, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-621)

Marion DeKalb Mason (1875–1946) was the long-time Johnson correspondent for the Springdale News. Writing under the penname “Mulkeepmo,” his columns were filled with neighborhood happenings, including news about the lime kilns.

Mason was a prolific and accomplished amateur photographer, shooting images first on glass plate and later on acetate film stock. He delighted in taking photos of family, friends, scenery, and local businesses, often printing the images on postcards and giving them away or mailing them to friends.

Mason lived with his sister and brother-in-law, Maud and Nathan Hanks, and their children in the Hanks home in Johnson, just down the road from the Johnson mill and the lime companies. It’s thanks to his writings and to the many generous folks who have shared his images (including Mason’s relatives) that the Shiloh Museum is able to preserve the rich history of Johnson’s lime industry.

Photo Gallery

2010-54-308

Men at the Crescent White Lime Works quarry, Johnson, April 22, 1901. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-308)

97-57-197

Sightseers on a limestone outcropping, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-197)

87-256-2

Miners at the Ozark White Lime quarry, Johnson, circa 1913. Ed Plumlee (4th from right), Ellis Plumlee (3rd from right), and Frank Plumlee (far right). Theresa Eubanks Collection (S-87-256-2)

2010-54-280

Miners at a quarry, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-280)

2010-96-22

Miners with a rock-filled tram car, Johnson, circa 1908. William R. Barnwell (far left). Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-2010-96-22)

78-34-57

Jim, Bert, and Sam on the tramway near the top of a kiln, Johnson, 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Phillip Steele Collection (S-78-34-57)

78-34-24

Hugh Lichlyter near the tramway and kiln, Fayetteville White Lime Company, Johnson, 1908. Ann Lichlyter Collection (S-2005-95-23)

97-57-144

Storm-damaged tramway, Fayetteville White Lime Company, Johnson, January 1909. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-144)

2010-54-299

Storm-damaged kiln and tramway, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, January 1909. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-299)

92-49-64

Miners at the Arkansas Lime Works, Garfield, circa 1910. Will Ross (behind right shoulder of man in center with shovel). Benton County History Book Collection (S-92-49-64)

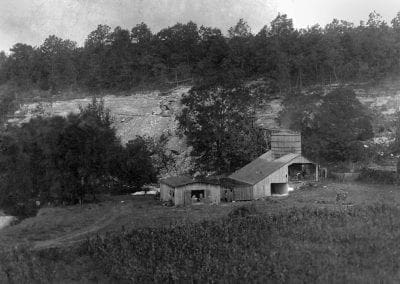

2010-54-307

Lime plant, Johnson, circa 1908. The plant had a kiln, a cooling floor, and a tramway leading from the bluff-side quarry to the top of the kiln. The buildings likely contained a barrel-making shop and a place to store wagons and other equipment. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-307)

2010-96-21

Kiln yard with stacks of cordwood, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-2010-96-21)

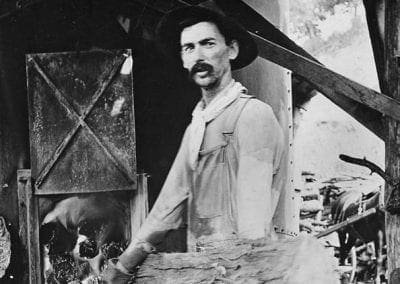

2010-54-295

Fireman stoking the kiln, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-295)

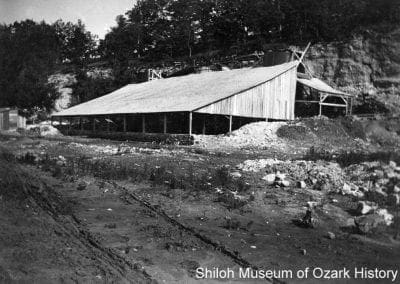

2010-54-278

New shed built to protect three kilns and the processed lime from flood damage, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-278)

2010-54-294

Workers on the cooling floor, shoveling quicklime into barrels, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-294)

78-34-67

Ozark White Lime Company executives at the Johnson Mill, Johnson, circa 1908. Former general manager E.C. Pritchard (left) and president Frank O. Gulley. Marion Mason, photographer. Phillip Steele Collection (S-78-34-67)

2010-54-325

Coopers with their barrels, probably Johnson, circa 1908. Don Bailey Collection (S-2010-54-325)

2012-61-3

Sacking room, Ozark White Lime Company, Johnson, 1920s–1930s. Grover Cordell Collection (S-2012-61-3)

2014-68

View from “Limekiln Bluff” of a Frisco Railroad train crossing the Clear Creek trestle, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Charlotte Steele Collection (S-2014-68)

Lime Companies in Northwest Arkansas

Finding reliable information about area lime plants is difficult. Below are the named plants we know about and the communties in which there were plants for which we have no names. If you have information or images about these or other area lime companies, please email our photo archivist/research librarian, Marie Demeroukas.

Sightseer at the lime quarry, Johnson, circa 1908. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-472)

Named Lime Plants

Alba Lime Company—Farmington

• Stock available July 1904; still in existence February 1909

• Three owners at first; company nearly went bankrupt; two owners left but property owner Alfred “Walter” Shreve stayed on

• Located on Goose Creek

• Employed many Italian immigrants from Tontitown

• Manufactured Eagle Brand Lime

Arkansas Lime Company—Benton County

• Had office in Rogers and short-lived plant in Lowell 1889

Arkansas Lime Works—Garfield

• Said to date to 1884; still in existence 1919

• Owned at one point by Peter McKinley

Brightwater Lime Company—Brightwater

• Investors looking for possible locations for new kiln, January 1907

• In existence April 1908

• J. D. Torbett, president

Crescent White Lime Works—Johnson

• In existence July 1891

• Owned by John W. Carter

• 20,000 bushels produced 1891; 35,000-40,000 bushels 1892; kiln could produce 80–100 barrels every 24 hours

• Lime shipped to various towns in Arkansas and to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma)

• Kiln rebuilt 1895 following fire

• Stone pier supporting tramway failed January 1897

• Purchased by Frank O. Gulley and E. A. Gillett December 1897; incorporated July 1899 with W. L. Stuckey, president; Frank O. Gulley, vice-president

• Renamed Ozark White Lime 1902

Crystal Lime Company—Johnson

• In existence September 1901, when it was said to be planning second kiln

• Still in existence February 1906

Excelsior White Lime Company—Prairie Grove

• In existence March 1907; still in existence October 1937

Fayetteville White Lime Company (a.k.a. Beane Lime Company)—Johnson

• Incorporated 1904 with C. P. Boles, president; S. C. Beane, vice-president

• Sold new kiln 1906 to Hays and Woods, who moved it to Prairie Grove

• Plant leased to “firm down south” October 1907, after being idle

Morrison White Lime Works—Garfield

• A booming business for several years, around 1900

• Absorbed by Ozark White Lime early 1900s

Ozark White Lime Company—Johnson

• Crescent White Lime renamed Ozark White Lime August 1902; bought Springdale Lime and Morrison White Lime around same time

• Operated five or six kilns at two lime plants near Clear Creek

• Opened Arkansas’ first lime-hydrating plant 1923

• Established rock-crushing plant 1938

• Ended production mid-1940s

Rogers Lime and Water-Works Company—Rogers

• Possibly incorporated January 1885

• In existence 1894

Rogers White Lime Company (a.k.a. Southern Lime Company?)—Johnson

• Located on the “Beane farm” (former Fayetteville White Lime plant)

• Started operation January 1908; idled March 1908

• Tramway blown down 1909; company never recovered

Rogers White Lime Company—Rogers

• Operated plant in Diamond Springs area 1893-1902

• Opened Cross Hollow plant (a.k.a. Limedale) 1902, with three kilns

• Product known as Lily White Lime

• Fleming Freeman president early 1900s to about 1917

• Steam-powered rock crusher added 1913

• By 1917 had additional kilns in Gravette and Grove, Oklahoma

• Entered bankruptcy 1918 due to financial woes and looming loss of rail service

Springdale Lime Company—Johnson

• In existence May 1901

• Absorbed by Ozark White Lime early 1900s

Tonti Lime Company—Washington County

• Incorporated November 1907 with Tontitown residents Luigi Tomiello, president; Giuseppe Roso, vice-president

• In existence 1913

Additional Lime Plants (Names Unknown)

Bethel Grove

• Possibly started 1902; lasted about 10 years

Brightwater

• In existence 1892

Garfield

• Possibly predecessor of Morrison White Lime

• Located on tributary of Sugar Creek; kiln on north side, quarry on south

• Tramways used to take stone from quarry to kiln, and from kiln to railway

• Operated by Peel and Benn, February 1884–November 1886

• Produced 86,300 barrels of lime and 50 rail carloads of bulk lime

• H. S. Dean owned business 1887–1888

• Shipped 15,000 barrels of lime and a few bulk carloads to towns in Arkansas and Kansas

• Plant idled Fall 1888

Gravette

• In existence by 1900s

• Lime shipped via Kansas City Southern Railway

• Deposit depleted by Ozark White Lime, 1910s or 1920s

Eureka Springs (north of Dairy Spring Hollow)

• In existence before 1891

• Burned small quantities of lime for Eureka Springs market

Eureka Springs (southwest of town)

• Owned by John Morehouse

• 9,000 bushels of lime burned 1890–1892

• Manufactured lime for Eureka Springs market

Harrison

• East of town on north bank of Crooked Creek

• In existence 1890

Johnson

• Said to be in operation around 1880

• First five years only a few hundred bushels produced for local use

• L. D. Middleton early owner

• Draw kiln built about 1887; over next three years 20,000+ bushels of lime were burned and shipped via Frisco to Ft. Smith, Van Buren, etc.

• Possibly became Crescent White Lime Works 1891 or earlier

Sulphur Springs

• Possibly in existence around 1910

Washington County (northern bluff of Baxter Mountain)

• Long abandoned by 1893

Washington County (W. F. Dowell place)

• Long abandoned by 1893

West Fork

• Possibly in operation 1893