A Better Bird

Online ExhibitWhich Came First?

Chickens going to market in G. A. Stroud Produce truck, Cave Springs, 1920s–1930s. Erline Littrell and Pat Simpson Collection (S-87-11-2)

Early settlers raised chickens primarily for their eggs. With the coming of the railroads in the 1880s, a few enterprising farmers and businessmen began shipping out fresh eggs and live chickens to distant markets. In 1893 Judge Millard Berry of Springdale purchased an incubator with a 200-egg capacity. This piece of equipment mimicked the hen’s ability to keep her eggs warm while the chicks grew slowly inside their shells.

At the time, Northwest Arkansas was home to a thriving commercial fruit industry. But problems with disease, changing weather patterns, crop failures, and an economic depression in the 1930s led some to seek other sources of income. The area’s largely hilly terrain and poor soil weren’t suitable for large-scale crop farming. Poultry production offered farmers a way to put their land and skills to work. They began raising broilers (young chickens), turkeys, and laying hens, the latter for their eggs.

Chickens going to market in G. A. Stroud Produce truck, Cave Springs, 1920s–1930s. Erline Littrell and Pat Simpson Collection (S-87-11-2)

Early settlers raised chickens primarily for their eggs. With the coming of the railroads in the 1880s, a few enterprising farmers and businessmen began shipping out fresh eggs and live chickens to distant markets. In 1893 Judge Millard Berry of Springdale purchased an incubator with a 200-egg capacity. This piece of equipment mimicked the hen’s ability to keep her eggs warm while the chicks grew slowly inside their shells.

At the time, Northwest Arkansas was home to a thriving commercial fruit industry. But problems with disease, changing weather patterns, crop failures, and an economic depression in the 1930s led some to seek other sources of income. The area’s largely hilly terrain and poor soil weren’t suitable for large-scale crop farming. Poultry production offered farmers a way to put their land and skills to work. They began raising broilers (young chickens), turkeys, and laying hens, the latter for their eggs.

What Led to a Successful Industry?

Boxed chicks at Brown’s LedBrest, Inc., Springdale, circa 1970. Robert Osburn Collection (S-2004-60-113)

As the poultry industry took off, others saw business opportunities in trucking, feed mills, equipment supply, and hatcheries (where eggs are hatched under artificial conditions). Centrally located railroads and highways allowed shipment to distant markets. Area banks were willing to make loans in order to fuel growth. Chief among them was the First State Bank of Springdale and its president Shelby Ford, the “Chicken Banker.” The building of Beaver Lake in the early 1960s provided a large-scale, sustainable source of water for the area’s ever-expanding chicken houses and processing plants. Low-cost labor from a largely non-union workforce helped keep overall costs down, then and now.

The early poultrymen knew the value of hard work and were willing to take chances. By investing in automation and making science-based improvements in such areas as genetic stock, disease control, and feed formulation, they were able to grow better birds while growing their businesses. Beginning in the 1950s vertical integration—the strategy of owning or controlling all aspects of a business in-house, from breeding stock to production and processing to transport and marketing—allowed large companies to grow even larger by trimming costs and managing the supply chain. Over time, Tyson Foods of Springdale transformed itself into a giant agribusinesses, in part by purchasing its competitors, expanding into the beef and pork industries, creating value-added products like pre-cooked meals, and establishing global markets.

For a time Springdale was known as “Chickendale,” because it was home to so many poultry businesses. Indeed, Washington and Benton Counties have always been the main engine of the area’s poultry industry and economy. A few of the big companies branched out in the mid-1980s, establishing grower, feed mill, and processing operations in neighboring Madison, Carroll, and Boone Counties.

What Led to a Successful Industry?

Boxed chicks at Brown’s LedBrest, Inc., Springdale, circa 1970. Robert Osburn Collection (S-2004-60-113)

As the poultry industry took off, others saw business opportunities in trucking, feed mills, equipment supply, and hatcheries (where eggs are hatched under artificial conditions). Centrally located railroads and highways allowed shipment to distant markets. Area banks were willing to make loans in order to fuel growth. Chief among them was the First State Bank of Springdale and its president Shelby Ford, the “Chicken Banker.” The building of Beaver Lake in the early 1960s provided a large-scale, sustainable source of water for the area’s ever-expanding chicken houses and processing plants. Low-cost labor from a largely non-union workforce helped keep overall costs down, then and now.

The early poultrymen knew the value of hard work and were willing to take chances. By investing in automation and making science-based improvements in such areas as genetic stock, disease control, and feed formulation, they were able to grow better birds while growing their businesses. Beginning in the 1950s vertical integration—the strategy of owning or controlling all aspects of a business in-house, from breeding stock to production and processing to transport and marketing—allowed large companies to grow even larger by trimming costs and managing the supply chain. Over time, Tyson Foods of Springdale transformed itself into a giant agribusinesses, in part by purchasing its competitors, expanding into the beef and pork industries, creating value-added products like pre-cooked meals, and establishing global markets.

For a time Springdale was known as “Chickendale,” because it was home to so many poultry businesses. Indeed, Washington and Benton Counties have always been the main engine of the area’s poultry industry and economy. A few of the big companies branched out in the mid-1980s, establishing grower, feed mill, and processing operations in neighboring Madison, Carroll, and Boone Counties.

A New Sense of Professionalism

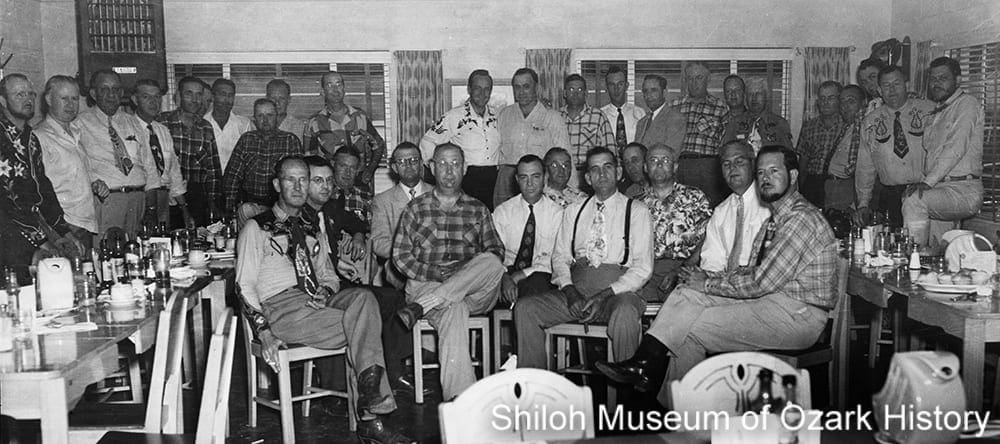

Arkansas Poultry Federation meeting, Springdale, early 1950s. Back row: Thurman “Shorty Parsons” (7th from left), Joe Steele (9th from left), Governor Sid McMath (10th from left), Roy Ritter (11th from left), Joe Robinson (12th from left), Governor Orval E. Faubus (9th from right), and Jeff Brown 6th from right. Front row: John Tyson (far left), Shelby Ford (5th from left), Elmer Johnson (5th from right), and Paul Condra (far right). LeAnn Ritter Underwood Collection (S-2012-31-19)

As poultry grew to prominence in Arkansas’ economy, the poultrymen looked to promote and professionalize their industry. In 1937 Bob Sharp held the first Northwest Arkansas Broiler Roundup at his farm near Lowell, offering over 2,000 farmers a chance to examine the newest production equipment. A year later, the first Northwest Arkansas Live Broiler Show was held in Rogers. An audience of roughly 15,000 viewed 900 birds from Arkansas and nearby states. Prizes were awarded to the top birds.

The Arkansas Poultry Federation was organized in 1954 with the initial goals of improving “the quality of poultry and eggs through research” and increasing the state’s consumption of broilers, turkeys, and eggs. The group tackled several issues, including exempting feed from state taxes and passing an egg-labeling law to maintain quality standards. Other poultry-related organizations like the Arkansas Turkey Federation, Arkansas Egg Council, Arkansas Poultry Producers Association, and Arkansas Allied Industries promoted and protected their interests. Not only were area poultrymen members of these organizations, they were their leaders, serving as board members and presidents.

A Changing Northwest Arkansas

There’s no doubt that Northwest Arkansas’ healthy economy and sizable population growth derives, in part, from the poultry industry, whether from the producers or the allied businesses which offer products and supplies. Thousands of jobs, both on the farm and in town, are tied directly to its success.

The industry’s need for a large workforce has fueled an influx of first- and second-generation migrants from other parts of the U.S. and the world, such as Latin America and the Marshall Islands. Indeed, this region is home to the world’s largest population of Marshallese outside of the islands thanks to John Moody, who joined Tyson Foods in the mid-1980s and spread the word back home about the need for workers. While some Northwest Arkansans are unhappy with the changes stemming from an increasingly diverse population, others embrace the traditions and cultural richness they bring.

A Changing Northwest Arkansas

There’s no doubt that Northwest Arkansas’ healthy economy and sizable population growth derives, in part, from the poultry industry, whether from the producers or the allied businesses which offer products and supplies. Thousands of jobs, both on the farm and in town, are tied directly to its success.

The industry’s need for a large workforce has fueled an influx of first- and second-generation migrants from other parts of the U.S. and the world, such as Latin America and the Marshall Islands. Indeed, this region is home to the world’s largest population of Marshallese outside of the islands thanks to John Moody, who joined Tyson Foods in the mid-1980s and spread the word back home about the need for workers. While some Northwest Arkansans are unhappy with the changes stemming from an increasingly diverse population, others embrace the traditions and cultural richness they bring.

Poultry Then and Now

Birth of an Industry

When Melvin L. Price formed the Ozark Poultry and Egg Co. in Fayetteville in 1915, he realized that the quality of local poultry and eggs was poor. He worked to improve breeding stock by swapping out his suppliers’ inferior roosters and turkeys with new, better birds. At first he shipped live birds to market by rail, later adding processed birds—chickens which had been killed, cleaned, and made ready for consumers.

About the same time a few farmers in Cave Springs used their slow winter months to grow broilers, young birds weighing two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half pounds. Their interest was spurred by Edith Glover Bagby, who hatched a few eggs in an incubator. After raising the birds she sold them at a profit. In 1919 Edith’s husband Earl Bagby, her father J. J. Glover, and Dave Boyd shipped a railroad carload of live birds to Chicago, receiving about $1.04 per bird. Area farmers took note of their success.

When Jeff Brown of Springdale had trouble with his fruit crop, he turned to raising broilers in 1921. Over the next few years he perfected his hatching and feeding techniques. In 1929 he convinced First National Bank of Springdale to lend him the money to start the Springdale Electric Hatchery, complete with an electrically heated, 10,000-egg-capacity commercial incubator. To ensure quality chicks, he became a licensed poultry inspector, which allowed him to blood-test his flocks for infection and disease.

“We shipped in young roosters from the North and exchanged them, pound for pound, for the scrub stock that was brought in [by the farmers]. The same procedure applied to turkeys, as we brought in fancy toms [male turkeys] and put them out to increase the quality of the flocks.”

Melvin L. Price, Ozark Poultry and Egg Co.

Flashback, November 1968

Birth of an Industry

When Melvin L. Price formed the Ozark Poultry and Egg Co. in Fayetteville in 1915, he realized that the quality of local poultry and eggs was poor. He worked to improve breeding stock by swapping out his suppliers’ inferior roosters and turkeys with new, better birds. At first he shipped live birds to market by rail, later adding processed birds—chickens which had been killed, cleaned, and made ready for consumers.

About the same time a few farmers in Cave Springs used their slow winter months to grow broilers, young birds weighing two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half pounds. Their interest was spurred by Edith Glover Bagby, who hatched a few eggs in an incubator. After raising the birds she sold them at a profit. In 1919 Edith’s husband Earl Bagby, her father J. J. Glover, and Dave Boyd shipped a railroad carload of live birds to Chicago, receiving about $1.04 per bird. Area farmers took note of their success.

When Jeff Brown of Springdale had trouble with his fruit crop, he turned to raising broilers in 1921. Over the next few years he perfected his hatching and feeding techniques. In 1929 he convinced First National Bank of Springdale to lend him the money to start the Springdale Electric Hatchery, complete with an electrically heated, 10,000-egg-capacity commercial incubator. To ensure quality chicks, he became a licensed poultry inspector, which allowed him to blood-test his flocks for infection and disease.

“We shipped in young roosters from the North and exchanged them, pound for pound, for the scrub stock that was brought in [by the farmers]. The same procedure applied to turkeys, as we brought in fancy toms [male turkeys] and put them out to increase the quality of the flocks.”

Melvin L. Price, Ozark Poultry and Egg Co.

Flashback, November 1968

Rise of the Poultrymen

John Tyson (left) and son Don Tyson at the Northwest Arkansas Poultry and Livestock Show, Springdale, 1955. V. D. McRoberts, photographer. Tyson Foods Collection (S-77-80-2)

Seeking new business opportunities, independent truckers and produce suppliers bought live birds to ship to distant markets. As the poultry industry grew, so did allied businesses—feed mills and feed stores, processing plants, equipment suppliers, and construction companies. Envisioning growth and progress, some businessmen diversified. In the 1930s John Tyson of Springdale used his truck to haul fruit in the summer and broilers in the winter, eventually saving up enough to buy a few hatcheries in 1942. From there he built a feed mill and then a processing plant. His son Don joined the business in the 1950s and helped take Tyson Foods to new heights.

As Northwest Arkansas’ reputation as a chicken capital grew, national companies like Campbell Soup, Ralston-Purina, Ocoma, and Armour established branch plants in Fayetteville, Springdale, Berryville, and Bentonville, respectively. But there were plenty of homegrown companies like George’s Inc. and Roy Ritter’s AQ Farm in Springdale, Simmons Industries in Siloam Springs, and Peterson Industries in Decatur. By 1950 Arkansas was the nation’s fourth-largest producer of commercial broilers. It was the third by 1955, the second in 1960, and the first-largest in 1970.

“Due to the economic value, the poultry industry has contributed an improvement to the level of Arkansas’ standard of living and it has been enjoyable to see a lot of people pull themselves up by the bootstraps to a good life. It has furnished many, many opportunities to people who would not have been otherwise so fortunate.”

Roy Ritter

Arkansas Poultry Times, October 29, 1976

Rise of the Poultrymen

John Tyson (left) and son Don Tyson at the Northwest Arkansas Poultry and Livestock Show, Springdale, 1955. V. D. McRoberts, photographer. Tyson Foods Collection (S-77-80-2)

Seeking new business opportunities, independent truckers and produce suppliers bought live birds to ship to distant markets. As the poultry industry grew, so did allied businesses—feed mills and feed stores, processing plants, equipment suppliers, and construction companies. Envisioning growth and progress, some businessmen diversified. In the 1930s John Tyson of Springdale used his truck to haul fruit in the summer and broilers in the winter, eventually saving up enough to buy a few hatcheries in 1942. From there he built a feed mill and then a processing plant. His son Don joined the business in the 1950s and helped take Tyson Foods to new heights.

As Northwest Arkansas’ reputation as a chicken capital grew, national companies like Campbell Soup, Ralston-Purina, Ocoma, and Armour established branch plants in Fayetteville, Springdale, Berryville, and Bentonville, respectively. But there were plenty of homegrown companies like George’s Inc. and Roy Ritter’s AQ Farm in Springdale, Simmons Industries in Siloam Springs, and Peterson Industries in Decatur. By 1950 Arkansas was the nation’s fourth-largest producer of commercial broilers. It was the third by 1955, the second in 1960, and the first-largest in 1970.

“Due to the economic value, the poultry industry has contributed an improvement to the level of Arkansas’ standard of living and it has been enjoyable to see a lot of people pull themselves up by the bootstraps to a good life. It has furnished many, many opportunities to people who would not have been otherwise so fortunate.”

Roy Ritter

Arkansas Poultry Times, October 29, 1976

Modern Growth

Len Yingst notes test results from Tyson Food’s new microwavable frozen-dinner product line, Springdale, March 1985. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 3/1985 #1)

In the early 1950s independent dealers bought broilers directly from farmers. But rising taxes and supply costs, coupled with market-price swings and too many poultry producers, led to uncertain profits for all. One way to boost profits was through mechanization. Instead of hand-feeding birds, machines like an auger feeder delivered feed automatically, allowing growers to switch from hauling heavy feed sacks to receiving bulk-feed shipments trucked in by the mills. Over the decades much of the work in processing plants was mechanized, including machines that kill the bird before opening and eviscerating it (removing its organs and intestines).

By the 1960s most broilers were produced under contract as part of a move towards vertical integration, a system which reduced a company’s costs by owning or controlling all aspects of production—research, breeding stock, hatcheries, feed mills, grower operations, processing plants, marketing programs, and distribution. Big producers like Tyson Foods grew larger, buying out its competitors. It also diversified by buying food-manufacturing companies and beef and pork producers, and developing value-added products like spicy “Buffalo Wings” for restaurants and home consumers. Tyson opened sales offices throughout the world, creating market-specific products such as bilingual packaging, custom seasoning blends, and specialty items prepared according to religious and government standards. Today Tyson is one of the largest protein producers on the planet.

“In the 1940s the success of the chicken broiler industry in Northwest Arkansas had attracted so much notice, that county agents and community representatives from all over the country came to this Ozarks Arkansas section to learn about the successful methods that had produced such substantial income to the local farmers.”

Ozarks Mountaineer, December 1953

Modern Growth

Len Yingst notes test results from Tyson Food’s new microwavable frozen-dinner product line, Springdale, March 1985. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 3/1985 #1)

In the early 1950s independent dealers bought broilers directly from farmers. But rising taxes and supply costs, coupled with market-price swings and too many poultry producers, led to uncertain profits for all. One way to boost profits was through mechanization. Instead of hand-feeding birds, machines like an auger feeder delivered feed automatically, allowing growers to switch from hauling heavy feed sacks to receiving bulk-feed shipments trucked in by the mills. Over the decades much of the work in processing plants was mechanized, including machines that kill the bird before opening and eviscerating it (removing its organs and intestines).

By the 1960s most broilers were produced under contract as part of a move towards vertical integration, a system which reduced a company’s costs by owning or controlling all aspects of production—research, breeding stock, hatcheries, feed mills, grower operations, processing plants, marketing programs, and distribution. Big producers like Tyson Foods grew larger, buying out its competitors. It also diversified by buying food-manufacturing companies and beef and pork producers, and developing value-added products like spicy “Buffalo Wings” for restaurants and home consumers. Tyson opened sales offices throughout the world, creating market-specific products such as bilingual packaging, custom seasoning blends, and specialty items prepared according to religious and government standards. Today Tyson is one of the largest protein producers on the planet.

“In the 1940s the success of the chicken broiler industry in Northwest Arkansas had attracted so much notice, that county agents and community representatives from all over the country came to this Ozarks Arkansas section to learn about the successful methods that had produced such substantial income to the local farmers.”

Ozarks Mountaineer, December 1953

Chickens of Today and Tomorrow

Jane Maginot tends her Freedom Ranger laying hens at Beyond Organics Farm near West Fork, December 4, 2020. With son Patrick and the chickens’ Great Pyrenees guard dog, Rusty.

Great strides have been made in the quest for better, faster-growing, healthier birds. Today they are increasingly raised in state-of-the-art grow-out houses (where a chick grows into a mature bird). Sensors and computers control temperature, feed, humidity, and light levels, which the grower can track and adjust by smartphone. As the poultry industry has grown, so too have concerns about the use of steroids (growth hormones) and antibiotics, the danger of food-borne illnesses like salmonella, the well-being of animals packed into massive grow-out houses, the effect of poultry waste on the environment, and the health, safety, and wages of workers. In 2011 the Cargill plant in Springdale recalled 36 million pounds of ground turkey, when it was linked to over seventy illnesses and one death from salmonella. While activists and industry leaders are working towards solutions to many of these issues, a new movement is on the rise, led by consumers and a few farmers and commercial producers.

Growing consumer interest in organic food, sustainability, and local agriculture has led to a rise in small-scale producers and farmers’ markets. In 2007 Little Portion Hermitage, a Catholic monastery near Eureka Springs, began raising chickens. Costing several-dollars-a-pound more than commercial birds, buyers appreciate that the free-range, steroid- and antibiotic-free chickens aren’t fed animal byproducts like ground-up feathers and bone meal. At Beyond Organics Farm near West Fork, James and Jane Maginot raise unconfined, open-pasture birds for meat and eggs, relying on their Pyrenees guard dogs to watch over their flocks of Rhode Island Reds, Freedom Rangers, and Ameraucana chickens. Because they approach agriculture holistically—as a set of interconnected systems—they pay attention to such things as soil health, seasonality, and the suitability of different livestock breeds for their area and farming style.

Mid-States Specialty Eggs, which opened a plant in Berryville in 2016, is a certified organic/humane company which contracts with independent growers to buy eggs from antibiotic-free hens that are either cage-free (birds roam around the layer house) or free-range (birds have outside access). Today Tyson Foods has reduced the amount of antibiotics it uses in its flocks. It also offers organic, antibiotic-free chicken through its NatureRaised Farms® brand.

“When you choose these birds over confinement birds [raised] by large growers, you are choosing to enhance your health. You also contribute to encouraging biodiversity, improving soil fertility and eliminating waste-management problems associated with confinement-feeding operations.”

From the Little Portion Hermitage website

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 13, 2008

Chickens of Today and Tomorrow

Jane Maginot tends her Freedom Ranger laying hens at Beyond Organics Farm near West Fork, December 4, 2020. With son Patrick and the chickens’ Great Pyrenees guard dog, Rusty.

Great strides have been made in the quest for better, faster-growing, healthier birds. Today they are increasingly raised in state-of-the-art grow-out houses (where a chick grows into a mature bird). Sensors and computers control temperature, feed, humidity, and light levels, which the grower can track and adjust by smartphone. As the poultry industry has grown, so too have concerns about the use of steroids (growth hormones) and antibiotics, the danger of food-borne illnesses like salmonella, the well-being of animals packed into massive grow-out houses, the effect of poultry waste on the environment, and the health, safety, and wages of workers. In 2011 the Cargill plant in Springdale recalled 36 million pounds of ground turkey, when it was linked to over seventy illnesses and one death from salmonella. While activists and industry leaders are working towards solutions to many of these issues, a new movement is on the rise, led by consumers and a few farmers and commercial producers.

Growing consumer interest in organic food, sustainability, and local agriculture has led to a rise in small-scale producers and farmers’ markets. In 2007 Little Portion Hermitage, a Catholic monastery near Eureka Springs, began raising chickens. Costing several-dollars-a-pound more than commercial birds, buyers appreciate that the free-range, steroid- and antibiotic-free chickens aren’t fed animal byproducts like ground-up feathers and bone meal. At Beyond Organics Farm near West Fork, James and Jane Maginot raise unconfined, open-pasture birds for meat and eggs, relying on their Pyrenees guard dogs to watch over their flocks of Rhode Island Reds, Freedom Rangers, and Ameraucana chickens. Because they approach agriculture holistically—as a set of interconnected systems—they pay attention to such things as soil health, seasonality, and the suitability of different livestock breeds for their area and farming style.

Mid-States Specialty Eggs, which opened a plant in Berryville in 2016, is a certified organic/humane company which contracts with independent growers to buy eggs from antibiotic-free hens that are either cage-free (birds roam around the layer house) or free-range (birds have outside access). Today Tyson Foods has reduced the amount of antibiotics it uses in its flocks. It also offers organic, antibiotic-free chicken through its NatureRaised Farms® brand.

“When you choose these birds over confinement birds [raised] by large growers, you are choosing to enhance your health. You also contribute to encouraging biodiversity, improving soil fertility and eliminating waste-management problems associated with confinement-feeding operations.”

From the Little Portion Hermitage website

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 13, 2008

Growing a Better Bird

Good Breeding

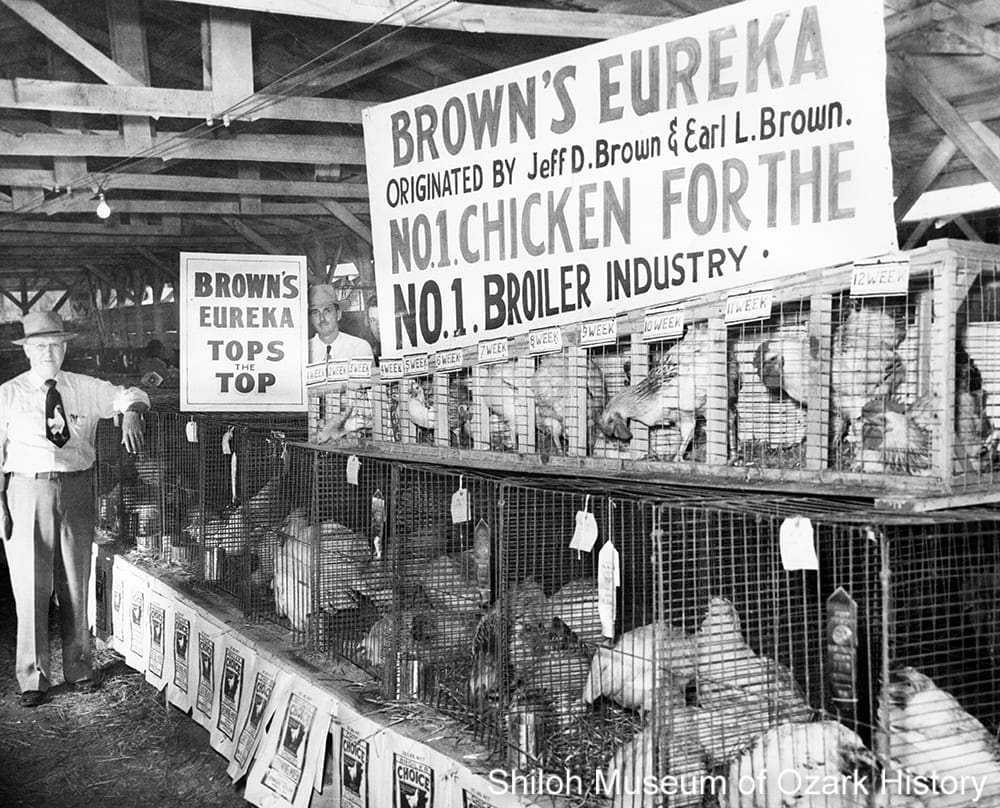

Jeff Brown with his Brown’s Eureka Broadbreast line of breeding stock at the Washington County Fair, Fayetteville, 1951. Howard Fowler, photographer. Anna Guest Brown Collection (S-82-60-33)

Early growers raised pure-bred birds like the White Wyandotte, White Plymouth Rock, and Barred Plymouth Rock. This preference continued into the early 1950s even though processors liked cross-bred birds better, such as the New Hampshire Cross (White Wyandotte male and New Hampshire female), because they had more white meat and were easier to prepare for the consumer. Careful breeding produced birds with bigger, meatier breasts which would grow at a faster rate, meaning that the farmer spent less on feed and was able to raise several flocks a year. In the 1940s it took fourteen to sixteen weeks to bring a flock to maturity. By the 1950s the growing period was reduced to ten to twelve weeks. Today’s broilers are ready in four to six weeks.

Birds were bred to be disease resistant and to produce white-feathered chickens, which consumers preferred over red-feathered birds, as the latter’s coloring gave a spotty appearance to the skin. Careful observation and record keeping allowed Springdale hatchery man Jeff Brown to develop Brown’s Eureka Broadbreast in 1946, a white-and-brown chicken with rapid growth. After ten years of research his son Gail introduced a better bird in 1958, the LedBrest Cockerel, one of the leading males in the 1960s. Other industry leaders included Arbor Acres, whose Tontitown facility could grow 50,000 White Rock females, and Peterson Industries of Decatur, which developed the Peterson Male in 1954. The company’s male line of birds had 70% of the U.S. market in the 1970s. Blake Evans of Decatur, founder Lloyd Peterson’s grandson, bred the Peterson Male with old-style birds in the late 2000s to develop the Crystal Lake Free Ranger, a rugged chicken with a strong immune system, which aimed to eliminate the need for antibiotics.

“As a boy . . . it became my responsibility to feed the farm poultry flock, gather the eggs, etc., and I soon learned the personality of each old hen and the characteristics of the different breeds. I remembered from year to year which hen set and hatched a brood of chicks first the previous year, and how many broods each hen raised.”

Jeff Brown, in an unpublished memoir, March 1951

The Science of Poultry

Taking a blood sample to test for disease, Springdale, 1960s. Guy Loyd, photographer. Lois J. Loyd Collection (S-99-125-290)

As the early poultrymen worked to breed a better bird and improve the health of their flock, some experimented with feed formulations, growing conditions, and hatching techniques, making detailed records of their results. In the early 1900s poultry diseases weren’t well understood. Young chickens died if they caught pullorum, which caused diarrhea. A program developed in cooperation with the Poultry Department of the University of Arkansas led to large-scale testing in the early 1930s, prompting Jeff Brown of Springdale to market his birds as pullorum-free, to reassure his customers. Later, as birds were crowded into giant broiler houses, they became more prone to disease. Researchers began experimenting with antibiotics as a way to treat them.

Competition from poultry producers in Maryland and Georgia caused researchers at the University of Arkansas to look for ways to produce a low-cost broiler which grew at a faster rate yet offered high nutritional value, as a way to revitalize the state’s rural areas. To that end the Agricultural Experiment Station studied poultry genetics, disease, feed formulation, and energy-efficient housing. In 1992 the College of Agriculture opened the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science, featuring classrooms, laboratories, a feed mill, and poultry-production facilities. As part of her work with the USDA-ARS Poultry Production and Product Safety Research Unit, in the early 2000s Dr. Annie Donoghue looked into the effect of probiotics (beneficial bacteria) on young turkeys. She tested whether probiotics could protect birds from pathogens (viruses and bacteria) which cause foodborne illness in humans.

“Oh, the poultry industry had several [diseases]. . . . They will have a coccidia problem [an intestinal parasite] and there will be some chemicals and compounds come along that will control it. And then a few years they lose their effectiveness and then a new [treatment] has to be developed. . . .Then we had Marek’s disease which is a skin tumor. . . .One thing that will always be with us—if we get one disease under control . . . there will always be a new one. We will never be without.”

Dr. Edward Stephenson, Department of Animal Industry and Veterinary Science, University of Arkansas

The Poultry Industry in Arkansas: An Oral History, 1989

Hatcheries

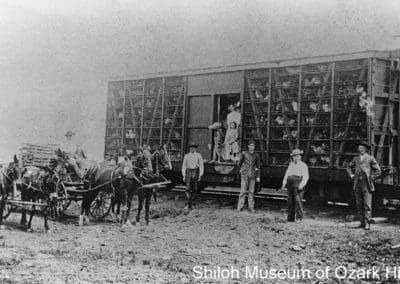

Inspecting eggs housed in an incubator at Tyson’s Feed and Hatchery, Springdale, June 1961. (S-94-179-118)

When a hen sits on her eggs, she stops laying additional eggs until her chicks can fend for themselves. An incubator acts like a mother hen, keeping an egg warm and turned so that the growing chick won’t stick to its shell. It can hold hundreds and even thousands of eggs all at once. In the early years incubators were heated by coal- or kerosene-burning stoves. Jeff Brown installed an electrically heated, 10,000-egg-capacity commercial incubator in his Springdale Electric Hatchery in 1929, the first of its kind in Arkansas. Soon other hatcheries opened, including the Johnson and Steele Hatchery in Springdale in 1935. Within one year they increased their hatching capacity fourfold, from 20,000 eggs to 80,000. Charles Vantress of California, the 1951 winner of the National Chicken-of-Tomorrow Contest, built a hatchery in Springdale in 1958.

In the mid-1980s eggs were incubated for nineteen days at 85% humidity and 99.5 degrees temperature while being turned automatically once an hour at Peterson Industries’ hatchery in Decatur. After two days in the incubator, the emerging chicks had their gender determined, their heath checked, and their beaks debeaked (blunted) and toenails clipped to prevent injuries or death to other birds. While the process is much the same today, new innovations have led to increased automation, greater biosecurity procedures to prevent the introduction of disease, and the need for fewer workers. Tyson Foods opened its $31 million Incubation Technology Center in Springdale in 2017, replacing two older hatcheries built in the 1960s and reducing staff needs from 55 to 35.

“Inside [Tyson’s new Incubation Technology Center], the processing line has updated technology including incubation hoods, injection stations, sanitation zones, sustainable ventilation, and six yellow robotic arms that handle repetitive tasks previously done by hatchery workers. The end result is the same: Eggs hatch into chicks in 21 days.”

Nathan Owens

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 24, 2017

From Farm to Table

Economics of Growing

Quality Feed Store and Hatchery, possibly Rogers, mid-1950s. Hubert L. Musteen, photographer. LeAnn Ritter Underwood Collection (S-2012-31-61)

At first farmers raised chickens on their own dime, purchasing feed and sending the birds to market. As the industry grew, a new business model arose. Area bankers like Shelby Ford of First State Bank in Springdale made significant loans to farmers for equipment and poultry houses, and to feed dealers and hatcheries who in turn gave credit to growers purchasing feed and chicks. The loans were repaid when the broilers were sent to market. But the growers took all the risks—from disease to adverse weather to low prices in weak markets. By the late 1940s the credit system had been adjusted. Farmers provided land, poultry houses, and labor while creditors provided chicks, feed, medicine, and transportation. Growers were paid a flat fee for each chicken produced, giving them a stable income. While credit allowed more farmers to grow bigger flocks, some didn’t like the terms of their contracts or their loss of independence. They were obligated to use the dealers’ feed—whether or not they liked it—at the dealer’s price. Also, they didn’t have control of processing or marketing costs. To even the playing field, farmers cooperatives were organized in Fayetteville in 1942 and later in Bentonville, Rogers, Gravette, and Siloam Springs. Co-ops offered its farmer members such services as financing, breeding stock, marketing, processing, and trucks to haul birds to market or to the processor. The need for co-ops started to fade as independent growers where edged out of the marketplace through the poultry companies’ move towards vertical integration.

“The FLOCK OWNER owns a flock of chickens, but takes little interest in working with the flock to get top results. . . .The POULTRYMAN . . . takes great interest in his flock . . . practices scientific methods . . . takes out all sick birds . . . Your hen is a partner with you in the ‘chicken business.’ Make her comfortable and she will prove her economic value to you in dollars and cents.”

Jeff Brown

Arkansas Poultry Improvement Association yearbook, 1949

Grower Operations

In the early 1900s broilers were a seasonal product, largely raised in the winter months for purchase from March to June. As the care and feeding of the birds became better understood, the industry took off. Following World War II many returning veterans began growing chickens, banking on cheap land and low start-up costs funded by loans. They often failed because of poor-quality chicks, lack of record keeping, and inadequate finances. Good growers worked hard to keep their birds healthy and growing. They hand-fed chicks until they learned about automatic feeders, doctored the birds, hosed them down with water to keep them cool in the summer, and dealt with equipment problems. The contract-growing system was developed in the 1950s. Poultry companies supplied growers with chicks and feed, contracting with them to raise the birds. Growers were paid by a “feed-conversion ratio,” meaning that they earned more if their birds gained weight quickly while eating less feed. Although this system helped reduce the grower’s risks, some felt the companies had too much power over them. Today’s companies require growers to continually invest in improved equipment and larger grow-out houses. In 2019, when Ed Milliken couldn’t afford to make the necessary changes to the outdated houses on his farm near Bella Vista, George’s Inc. paid him to drop out of the business. They weren’t obligated to do so, but Milliken appreciated the “gracious gesture.”

“I just can’t recommend [raising chickens] to anybody thinking about going into it. There isn’t a future in it—the cost of everything you put into it far outweighs what you’re paid. . . . They want the growers to change the [equipment] constantly. You can’t get one piece of equipment paid for before they want you to buy something else.”

Jewell Proctor of Lincoln Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 17, 1993

Grow-out Operations

Chicken farm, Springdale, 1940s. Gene H. Thompson, photographer. Gene H. Thompson Collection (S-96-56-28)

In the early 1900s chickens roamed freely outdoors. Their coops were small, designed to protect them from predators. But as the poultry industry grew, so too did the sizes of grow-out houses, which confined the growing birds for much of their lives. In the late 1930s there were about 5,000 chicken houses in Northwest Arkansas, roughly 12-by-14 feet in size, each holding about 500 birds. Many of these structures were insulated with paper and heated by coal-burning stoves. By the early 1950s the houses were up to 40-feet wide and 300 to 400 feet long, capable of housing between 10,000 to 50,000 birds.

New innovations came along to keep chickens healthy and growing, reduce mortality (death) rates, and allow for year-long production—continuous lighting to keep birds eating around the clock, improved ventilation, heating and cooling, and mechanical feeding and watering. Today’s modern technology allows computers to gather data from sensors to adjust temperature automatically, monitor feed levels, and activate sprinklers to keep the birds cool. Kirk Houtchens, a contract grower for George’s Inc., spent nearly $4 million to build four state-of-the-art grow-out houses in Decatur. In 2014 he was able to raise 140,000 broilers a month, 48,000 more than the year before.

“It’s easy to tell when the birds are sick. I usually come in late at night and whistle, which stirs them up. After they quit running around, I listen carefully to see if I hear any wheezing noises. Sometimes, if we suspect there might be trouble, we cut four or five open just to inspect their lungs, and look for any abnormalities.”

Elton Youngblood of Berryville

Carroll County News, June 1987

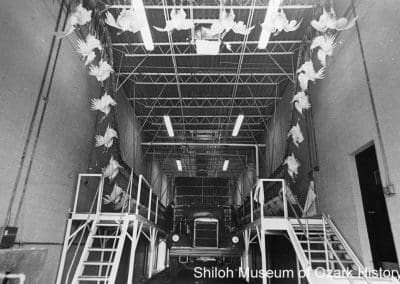

Processing Plants

Processing line at Springdale Farms, Springdale, 1958. Guy Loyd, photographer. June Loyd Collection (S-2009-31-165)

In the early 1900s birds were processed entirely by hand, often in poorly lit rooms with inadequate sanitation and air circulation. Major national meat packers like Swift, Amour, and Campbell Soup established processing plants in the area in the 1940s and 1950s, joining the many small, independent plants which popped up after World War II. Springdale Farms, the first modern processing plant in Springdale, was built in 1958. Operated by Edgar Loyd and his sons Jack, Landreth, and Guy, the $200,000 plant featured bright fluorescent lights, glazed-tile walls and stainless-steel processing lines for easy sanitation, and a government-inspector’s station at the start of the eviscerating line (where a bird’s organs and intestines are removed). The plant’s design met new federal standards and allowed for mandatory inspections to ensure the safety of chicken sold across state lines. Smaller processors which couldn’t afford expensive renovations to meet these standards went out of business.

When a flock reached its market weight the birds were caught, caged, and trucked to a processing plant. There they were attached by their feet to a moving line to be killed and bled before being scalded, picked (plucked), and singed to remove their feathers. Guts and internal organs were removed and the cavity cleaned. After being inspected for disease, the birds were cut-up, weighed, packaged, and chilled. The process is similar today, but much faster due to advances in automation. Tens of thousands of birds can be processed in a 24-hour shift. The work is fast-moving, physically demanding, loud, unpleasant, and dangerous. Some consumers object to what they call “factory chicken,” choosing instead to buy chickens raised on small-scale farms. Beginning in 2004 some of those birds were processed by Das Butcher Haus, a custom slaughterhouse near Green Forest run by Eldon Shrock.

“Those who worked in the basement of Jerpe’s [Dairy Products Co.], as I did for three years in the [1930s], were the cast offs from Fayetteville society. . . .Its stink could be smelled blocks away. . . .women pulled wet feathers from the fowls as fast as they could for this was piecework [and the women were paid according to how many birds they could process]. . . .Handling wet chickens and standing on piles of feathers and droppings, fingers and toes would soon be covered with red and weeping blisters . . . to us it was the chicken itch. . . .Killing began at seven and we might be there until ten that night.”

Ethel Edwards

History of Washington County Arkansas, 1989

Beyond Chickens

Table-Egg Operations

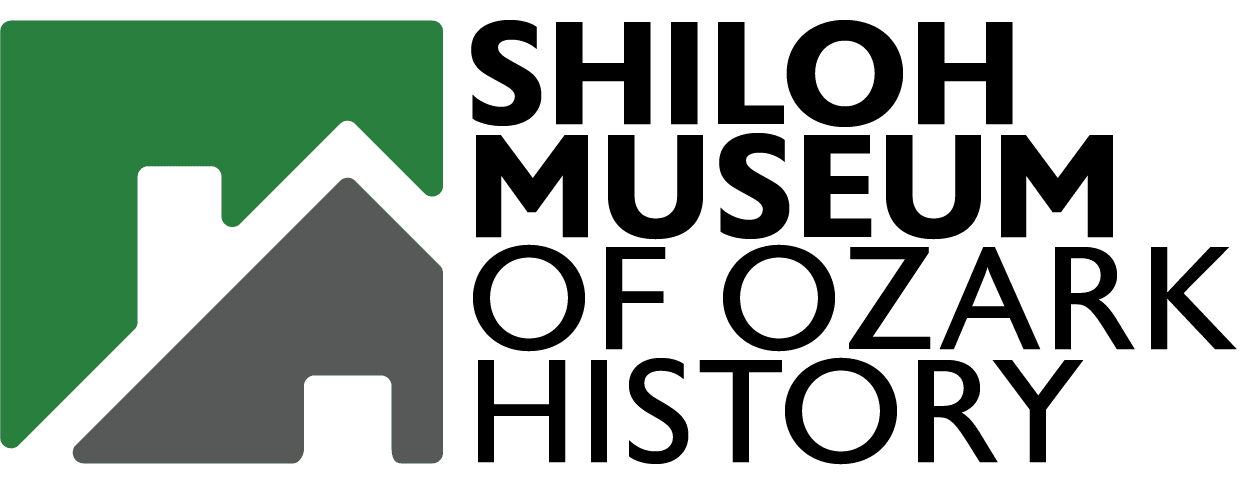

Fox Deluxe cage farm, Rogers, January 1956. Gene Thompson, photographer. Steve Thompson Collection (S-2015-78-812)

Beginning in the mid-1910s table eggs (as opposed to eggs produced for hatching) were sold by Fayetteville’s Ozark Poultry and Egg Co. Back then laying hens were allowed to roam outdoors, eating insects, household scraps, and home-grown grain. As the commercial egg industry grew, hens were moved into large houses and later, packed into row upon row of cages. In 1984 Dick Latta of Lincoln had 450,000 hens. Each day they ate 42 tons of food and produced about 336,000 eggs (60 million annually). Once laid, the eggs rolled onto a conveyor belt to be washed, inspected, graded, and packaged.

Improved management, caged birds, and higher-quality chicks and feed have led to increased egg production. But at what price? Activists concerned about the birds’ well-being have called for change, including cage-free housing, in part to prevent weak and brittle bones caused when the birds can’t move around and stretch their wings. Mid-States Specialty Eggs opened a certified organic/humane plant in Berryville in 2016. They produce specialty eggs including cage-free (birds can roam around the layer house) and free-range (birds have outside access).

Beginning in 1956 Arkansas required all table eggs to be graded for quality. Expert graders examine each egg as it passes over a strong beam of light, looking for flaws like small blood spots. Top quality Grade A eggs are sold in grocery stores. Flawed but edible eggs are sent to egg-breaking plants where they are turned into a liquid, dehydrated (dried), or frozen product for institutional or industrial use, such as schools and commercial bakeries. During World War II the Jerpe Dairy Product Co. of Fayetteville dehydrated up to 720,000 eggs daily, producing powdered eggs to help feed the country’s armed forces. In 1970 Springdale voters approved a $750,000 municipal bond issue to finance the construction of the Seymour Foods plant. At the time, it was one of the four largest egg-breaking facilities in the country, processing 360,000 eggs daily.

“Next step for Madam Hen’s product is the breaking room [at Jerpe Dairy Products Co.]. Here . . . girls in white uniforms and having first passed their hands through a sterilizer, work before breaking machines with a steel blade centering two metal ‘Irish Suckers,’ [which] neatly clips each egg in half and scoops the content . . . into a container below, [with the shells] . . . used locally for fertilizer.”

Lessie S. Read

Northwest Arkansas Times, May 18, 1943

Turkeys

Cuba Wilson Williams at her and her husband Hugh Williams’ turkey farm, Elkins, 1952. Roma Ambrose Collection (S-87-86-27)

Ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday in 1929 over 1,200 birds from Huntsville, Marble, Kingston, and elsewhere were rounded up and transported by truck to the railroad depot to be shipped to market. Back then turkeys were luxury food. Hugh Williams of Elkins started growing commercial turkeys in 1936, later saying, “There just was no science to turkey growing. . . It was just a haphazard thing and we had a lot to learn.” Labor and feed costs plus adverse weather like heavy rains, cold temperatures, and hail made growing turkeys outdoors difficult. Williams credited his early success to a “strict sanitation program and running turkeys on new ground” to lessen the chance of infection.

When Roy Ritter of Springdale began raising turkeys, he’d make double use of his chicken houses. He’d start his turkeys in them for about six weeks and, after moving the birds outside, began raising broilers in the house. In later years Ritter became president of the Arkansas Turkey Federation and the National Turkey Federation and worked with George’s turkey operation in the 1960s.

In 1955 Berryville had numerous turkey farms and was home to the state’s largest turkey hatchery and the Ocoma Processing Co., which employed over 400 people. Turkey was a $3.5 million business, causing folks to claim Berryville as the “Turkey Capital of Arkansas.” Today Springdale is home to Cargill, Inc., the largest turkey-processing facility in the state. In 1995 the company’s hatchery in Gentry hatched out 250,000 eggs weekly, about $10 million annually. These days the Butterball turkey processing plant in Huntsville stays busy during the 38-day holiday season, processing fresh, whole turkeys for consumers who don’t want a frozen bird. As an incentive, workers receive overtime pay and bonuses. Weekend workers are treated to snacks, prize-drawings, and sometimes food from local vendors.

“The people are not buying. Last year when turkeys were selling for $5 each, we shipped more than 40,000 pounds from this point, and couldn’t supply the demand. This year turkeys are selling for $8 and there is no market. . . .Financial conditions in the East have had something to do with the slump in turkey shipments. People haven’t made any money and they are not going to have expensive Thanksgiving dinners.”

Melvin L. Price, Ozark Poultry and Egg Co.

Fayetteville Daily Democrat, November 22, 1922

Allied Industries

Feed Mills

Ralston-Purina Co. feed mill, Springdale, May 12, 1964. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-84-113-83)

It costs money to feed and house poultry, cutting into a grower’s profit margin. In the 1930s some growers made their own feed blends while others used commercial feeds such as starting mash (finely ground feed) for chicks and growing mash for older birds. They supplemented the birds’ diet with yellow cornmeal and milk to improve their nutrition and fatten them. Early on, suppliers mixed feed manually, with shovels. In the late 1930s Jeff Brown installed factory-built mixers at his Springdale feed mill.

In 1940 it took four and one-half pounds of feed to produce one pound of broiler meat over a twelve-to-sixteen-week growing cycle. In 1966 it only took two and one-half pounds of feed and nine weeks. The difference was in the diet. Modern feed was packed with such things as vitamins, amino acids, minerals, corn, soybean meal, and fish meal. Growers largely fed their birds commercial feed, either made by locally owned feed mills like George’s or by national companies which began setting up shop in Northwest Arkansas in the late 1940s. Ralston-Purina came to Springdale in 1955, building a massive facility painted with its trademark red-and-white checkerboard. The all-steel mill was capable of processing 5,000 tons of Purina Poultry Chow monthly. With interest growing in organic food and small-scale poultry farms, in 2002 Kathy Clifft started the Doubletree Ranch feed mill near the Huntsville square, selling organic feed to folks raising small livestock as food for themselves or to sell to others.

“[When we first started mixing feed] . . . we’d dump in the ingredients like corn meal and mill feed and meat scraps and probably a sack of fish meal and whatever scraps. Then we’d . . . work the ingredients like people mix concrete with a shovel. . . .Back in those days we didn’t know about vitamins or coccidiostats (a type of medicine). We did know about cod-liver oil, so we used it.”

Ford Buckner

Lloyd Peterson and Peterson Industries: An American Story, 1989

Transportation

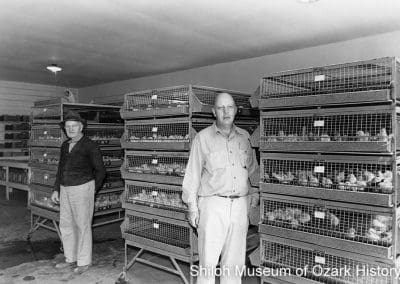

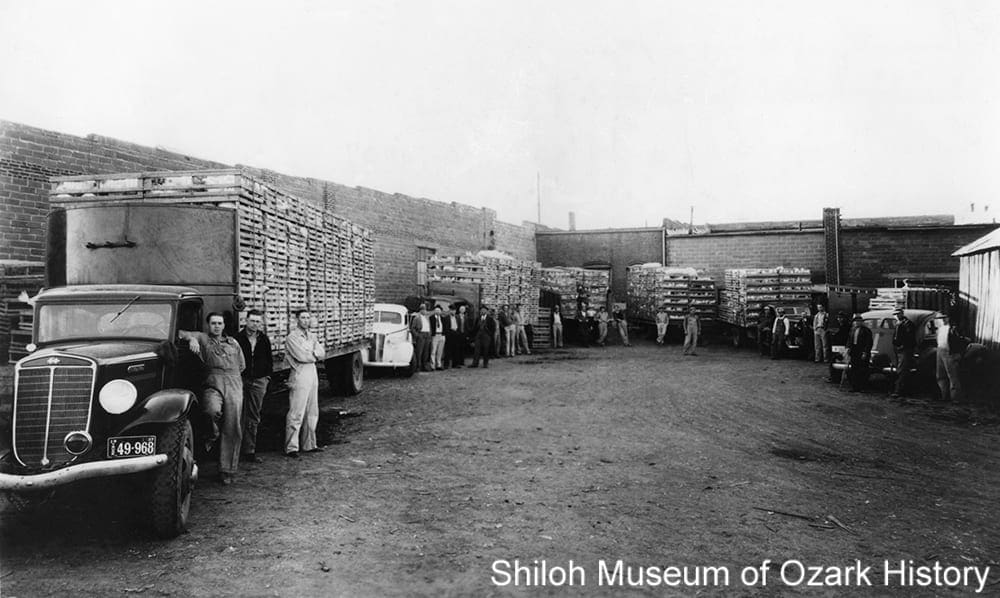

George’s Inc. trucks loaded for market with live chickens, Springdale, May 1937. With Luther George, third from left. George’s Inc. Collection (S-78-29-4)

At first live poultry and eggs were shipped by rail in huge carloads to distant markets. Some processed birds—chickens which had been killed, cleaned, and made ready for consumers—were shipped too, transported in railroad cars packed with ice and salt. From the 1920s to the 1930s farmers often sold live birds to independent long-haul truckers or local produce dealers. Their mobility allowed them to transport chickens to markets in big cities like Chicago, St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Kansas City on their own schedule, not that of the railroad.

Some haulers used customized trailers nicknamed “poultry Pullmans” to make it easier to feed and water the birds along the way and provide a small sleeping compartment for the driver. Back then it took thirty hours to reach Chicago. Produce dealer Joe Robinson of Springdale used his fleet of fifty trucks to haul birds to both coasts, bragging that he could “haul as far as Europe if a bridge was built.” In the 1950s the industry shifted from shipping live birds to packaged, fresh meat in ice-filled refrigerated trucks. Frozen meat became more popular in the 1960s with both consumers and producers—the latter because, without the need for ice, a truck could carry more meat for the same cost.

Baby chicks needing to travel long distances were flown in airplanes. At first Ray Ellis of Fayetteville brought in chicks from distant hatcheries through his company, South Central Air Transport, Inc. (SCAT). But an increase in local chick production meant that by the early 1950s he was flying them out of the area. SCAT planes also were used to transport poultry personnel, bring in veterinarians and medicine, and take sick birds to laboratories for testing. In 1985 Peterson Industries of Decatur had its own fleet of planes to deliver chicks across the country.

“[In 1933 C. L.] George set out for the Windy City [Chicago] with 8,000 [of my] chickens in coops on a truck, followed by a flatbed truck holding 100-pound bags of feed and feeders. George would stop every 50 to 100 miles or so, find a field and ask the owner for permission to feed the chickens. Then he would set up the coops out in rows on a field, set up the feeders . . .and give them some water. I didn’t hear from him for about a week and then one day he drove up, jumped out and said, ‘Hot dog! Let’s do it again.’ I asked ‘Did you make some money, Charlie?’ and he said $300!'”

Elza Hultz

Northwest Arkansas Times, March 22, 1990

Bird is the Word

Events

Arkansas Broiler Hatchery float in the National Chicken-of-Tomorrow Contest parade, Fayetteville, June 15, 1951. Roy’s Photoshop, photographer. J. Dickson Black Collection (S-92-142-15)

In 1951 the University of Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station hosted the National Chicken-of-Tomorrow Contest. It challenged poultry breeders to create the ideal chicken, one with a broader breast, thicker drumsticks, and a smooth, unblemished skin free from pinfeathers (small, newly grown feathers). Charles Vantress of California was the winner with his cross-bred bird, which went against conventional wisdom, that a pure-bred bird was best. His win transformed the industry. The contest was also a way to promote Arkansas’ growing prominence as a poultry producer. The local arrangements committee was a Who’s Who of industry leaders, and boy, did they put on a show for the contest’s 30,000 visitors. There was a beauty pageant, a three-mile-long parade, an awards ceremony and formal ball, a gigantic street dance featuring Leon McAuliffe and his Western Swing Band, scenic tours, exhibition booths, poultry talks, an address by U.S. Vice-President Alben Barkley, and a barbecued chicken dinner for 3,500 at Lake Wedington.

The first annual Northwest Arkansas Live Broiler Show was held in Rogers in 1939, drawing thousands of visitors and hundreds of birds. The following year Springdale served as host, with a banquet, speeches, and exhibits of birds, suppliers, and equipment. The Springdale Jaycees (Junior Chamber of Commerce) held “drumstick parties” at the Jaycee’s national conventions in the 1950s and 1960s. A popular event, convention-goers lined up to get free drumsticks largely furnished by Northwest Arkansas companies and prepared by the AQ Chicken House. Over 20,000 drumsticks were given out at in Atlanta in 1961. Each year a young woman appeared as “Miss Chic,” holding a giant artificial drumstick and wearing a white bathing suit and a hat shaped like a roosting hen. From 1960 to 1976 Springdale hosted the Northwest Arkansas Poultry Festival, sponsored by the Arkansas Poultry Federation as a way to “gain more respect and prestige for the . . . poultry industry . . . and to promote increased consumption of poultry products.” Activities included fried chicken dinners, cooking and barbecue contests, a beauty pageant, hatchery and processing-plant tours, and a parade.

“Folks even locally, became broiler conscious [because of the Northwest Arkansas Live Broiler Show]. A greater record has been made in sales by local merchants than in many years past, if ever, following the January, 1939, exhibit. Cafés, cafeterias, roadhouses and restaurants and hotel dining room managers throughout the year have featured broiler dinners for the big events until the ‘Arkansas broiler dinner’ has become a sort of slogan for Washington and Benton Counties.”

Springdale News, January 11, 1940

Marketing

Preparing Swanson fried-chicken TV dinners at Campbell Soup, Fayetteville, 1956. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 50 G-21)

Early growers wanted a faster-growing bird, but what did consumers want? In the 1950s most fresh chickens were sold “New York dressed,” meaning that the birds still had their heads, feet, and internal organs. The rise of supermarkets and the middle-class led to the desire for a ready-to-cook bird. By the 1960s processors began cutting chickens into pieces and packaging them under their own names rather than that of the grocery store, as a way to build up their brands. The American housewife also had a say in the look of the bird, which she wanted to be meatier and uniform in size, with clean-looking skin. Chickens with white feathers have white skin, while the skin of red-feathered chickens is colored and spotty. Convenience foods such as pre-cooked, frozen TV dinners appealed to women who were entering the workforce but still had families to feed. TV dinners with chicken were produced by the Campbell Soup plant in Fayetteville beginning in the mid-1950s, under its Swanson brand.

Consumers’ changing diets and eating habits in the 1970s encouraged companies to offer new consumer-ready food products. Chicken was marketed as an inexpensive, low-fat source of protein. An increasing demand for convenience foods for home and fast-food franchises led to such products as microwaveable meals, pre-cooked chicken nuggets, and refrigerated fresh entrées. Today chicken parts are often further processed by having bones and skin removed. Value-added products like these offer the companies a greater monetary return for their investment.

“We take the meat off the bone and make various forms and shapes. . . .Some breading is heavy . . . some’s crispy, some picks up grease. . . .in the South, as an example, people will eat a lot more greasy chicken than they will in the North. So in the Southern part of the U.S. we have a breading that picks up probably 10 pounds of grease per 100 pounds of chicken and in the North we make a real crispy one and it picks up 6½ pounds of grease . . . So you make a product for that region.”

Don Tyson

The Poultry Industry in Arkansas: An Oral History, 1989

Challenges

Workplace Diversity

Chick sexers at Brown’s Hatchery, Springdale, 1960s. Guy Loyd, photographer. Lois J. Loyd Collection (S-99-125-330)

While a few African-Americans worked as laborers at the Ozark Poultry and Egg Co. in Fayetteville in the late 1910s, nearly all of Northwest Arkansas’ poultry-industry workers where white, reflecting the community at large. That began to change after World War II when a few men and women of Japanese ancestry worked at the hatcheries as chick sexers. Folks in Japan first determined how to sex chicks in the 1920s. Sexing was a highly skilled, well-paid job, requiring the worker to instantly determine a bird’s gender without hurting it. In the 1980s large numbers of Latin Americans began working in processing plants, followed by Marshallese and Southeast Asians. In 2016 33% of Arkansas poultry workers were Hispanic or Latino, 17% African American, and 6% Asian (largely from the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific).

In the 1990s the area’s low-unemployment rate led to labor shortages in poultry-processing plants. Over the decade nearly 20,000 Latinos, largely from Mexico, moved into Northwest Arkansas, especially Rogers. Some white residents didn’t like the changes happening in their community including Dan Morris, who founded Americans for an Immigration Moratorium. His argument for a crackdown on illegal immigration mirrored growing beliefs in some segments of the U.S. population. In 1995 officers with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service conducted “Operation South PAW” [Protect American Workers], two days of raids at poultry-processing plants in Rogers, Siloam Springs, Springdale, and Huntsville. About 117 folks said to be from Mexico and Central America were detained and transported by bus to Fort Smith for further processing. Representatives from area food-processing industries decried the raids, saying that the workers weren’t taking jobs from Americans.

“Anyone who says Hispanics are taking jobs from native workers is ignorant. It’s racist. We wouldn’t be having this discussion . . . if there were white folks moving here for jobs.”

Rogers Mayor John Sampier

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 23, 1997

Worker Rights and Conditions

George’s Inc. billboard thanking employees in English, Spanish, and Marshallese for their work during the global COVID-19 pandemic, Springdale, November 30, 2020.

According to a 2016 report by the Northwest Arkansas Workers’ Justice Center, while Arkansas poultry workers are typically paid more than the minimum hourly wage, they still fall well below a living wage for this area. Non-white and foreign-born workers reported “some form of illegal wage theft,” including not receiving overtime pay or not being paid for all of the hours they worked. Processors have offered some benefits like childcare and health insurance, but the workers said the latter was unaffordable. Many worked while sick, saying, “they did not have earned-sick leave and needed the money.” Some reported that their employer used a point system to monitor a worker’s absence due to illness, injury, or care of family members. Even the length of bathroom breaks was monitored. Too many points and a worker could be disciplined or let go.

Poultry processing is fast-paced, repetitive work under difficult working conditions, leading to injuries from knives and nerve damage. Employee turnover is high. Companies have tried to reduce repetitive motions by redesigning tools, introducing strengthening exercises, and cross-training employees to work at several different jobs. In 2020 poultry-processing workers faced a new threat—COVID-19. Declared “essential workers” by the U.S. government, companies implemented protective measures such as providing face masks, conducting wellness screenings, designating social-distance monitors, and installing plastic barriers between workers who stand close together on the processing line. But many workers said they didn’t feel safe. By August 2020 more than 20% of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Benton and Washington counties involved poultry workers—over 1,000 people in each county.

“The supervisors get mad at us because [women] take longer [in the bathroom] . . . our needs are greater than those of men. They don’t consider that we have more gear to remove or the fact that the bathrooms are too far away; just walking towards them our time is up. When we have our menstrual cycle, we need to go more often . . . but they don’t let us, they don’t like it.”

Woman Poultry Worker #2

Wages and Working Conditions in Arkansas Poultry Plants, February 1, 2016

Worker Rights and Conditions

George’s Inc. billboard thanking employees in English, Spanish, and Marshallese for their work during the global COVID-19 pandemic, Springdale, November 30, 2020.

According to a 2016 report by the Northwest Arkansas Workers’ Justice Center, while Arkansas poultry workers are typically paid more than the minimum hourly wage, they still fall well below a living wage for this area. Non-white and foreign-born workers reported “some form of illegal wage theft,” including not receiving overtime pay or not being paid for all of the hours they worked. Processors have offered some benefits like childcare and health insurance, but the workers said the latter was unaffordable. Many worked while sick, saying, “they did not have earned-sick leave and needed the money.” Some reported that their employer used a point system to monitor a worker’s absence due to illness, injury, or care of family members. Even the length of bathroom breaks was monitored. Too many points and a worker could be disciplined or let go.

Poultry processing is fast-paced, repetitive work under difficult working conditions, leading to injuries from knives and nerve damage. Employee turnover is high. Companies have tried to reduce repetitive motions by redesigning tools, introducing strengthening exercises, and cross-training employees to work at several different jobs. In 2020 poultry-processing workers faced a new threat—COVID-19. Declared “essential workers” by the U.S. government, companies implemented protective measures such as providing face masks, conducting wellness screenings, designating social-distance monitors, and installing plastic barriers between workers who stand close together on the processing line. But many workers said they didn’t feel safe. By August 2020 more than 20% of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Benton and Washington counties involved poultry workers—over 1,000 people in each county.

“The supervisors get mad at us because [women] take longer [in the bathroom] . . . our needs are greater than those of men. They don’t consider that we have more gear to remove or the fact that the bathrooms are too far away; just walking towards them our time is up. When we have our menstrual cycle, we need to go more often . . . but they don’t let us, they don’t like it.”

Woman Poultry Worker #2

Wages and Working Conditions in Arkansas Poultry Plants, February 1, 2016

Environmental Challenges

Scott Becton (left) and Dr. Philip A. Moore Jr. collect water-runoff samples from a Madison County farm, 2006. Stephen Ausmus, photographer. Courtesy USDA Agricultural Research Service (D645-1)

As the poultry industry has scaled up, so too has its strain on the environment. One grow-out house can produce about 100 tons of chicken litter—a mixture of feathers, chicken manure, and bedding material like rice hulls or wood shavings. The nitrogen and phosphorus in litter can be a useful fertilizer when properly applied to fields. But too much litter on hilly pasture lands can lead to runoff, polluting streams and aquifers (underground pools of water). That’s what Oklahoma claimed was happening to the Illinois River and other streams along its border with Arkansas. A multi-year dispute between state and local governments, poultry companies, and farmers ensued, followed by a lawsuit in 2005 which, as of November 2020, has yet to be settled. In the 1990s Dr. Philip A. Moore Jr. of the USDA-ARS Poultry Production and Product Safety Research Unit at the University of Arkansas’ Center of Excellence for Poultry Science treated poultry litter with alum to reduce phosphorus runoff from pastures.

Processing poultry is water-intensive. In the late 1970s plants discharged nearly thirty million gallons of greasy water each month, at times overwhelming municipal water-treatment facilities which were unable to process it adequately. Environmentalists squared off against poultry leaders, who threatened to move their operations to areas with less stringent water quality standards. As a result some standards were lowered. Fayetteville provided monetary assistance to upgrade Campbell Soup’s water pretreatment, as one solution to pollution in the White River. In Huntsville, Butterball treated about one million gallons of wastewater with chemicals daily in two open lagoons (ponds) before sending it to the town’s water-treatment plant. But the fat and meat remnants in the water caused a stink, forcing Butterball to build a 1.7-million-gallon storage tank in 2018 to pretreat its wastewater.

“You can’t often see the pollution itself, but you can see the result. When the water becomes overloaded with nutrients algae begins to grow wildly as do some other aquatic plants. This wild growth deprives the water of necessary oxygen. If the situation persists the result is scummy green water, dead fish and plants, evil smells, and so forth.”

Joe Neal

Grapevine, September 6, 1978

Environmental Challenges

Scott Becton (left) and Dr. Philip A. Moore Jr. collect water-runoff samples from a Madison County farm, 2006. Stephen Ausmus, photographer. Courtesy USDA Agricultural Research Service (D645-1)

As the poultry industry has scaled up, so too has its strain on the environment. One grow-out house can produce about 100 tons of chicken litter—a mixture of feathers, chicken manure, and bedding material like rice hulls or wood shavings. The nitrogen and phosphorus in litter can be a useful fertilizer when properly applied to fields. But too much litter on hilly pasture lands can lead to runoff, polluting streams and aquifers (underground pools of water). That’s what Oklahoma claimed was happening to the Illinois River and other streams along its border with Arkansas. A multi-year dispute between state and local governments, poultry companies, and farmers ensued, followed by a lawsuit in 2005 which, as of November 2020, has yet to be settled. In the 1990s Dr. Philip A. Moore Jr. of the USDA-ARS Poultry Production and Product Safety Research Unit at the University of Arkansas’ Center of Excellence for Poultry Science treated poultry litter with alum to reduce phosphorus runoff from pastures.

Processing poultry is water-intensive. In the late 1970s plants discharged nearly thirty million gallons of greasy water each month, at times overwhelming municipal water-treatment facilities which were unable to process it adequately. Environmentalists squared off against poultry leaders, who threatened to move their operations to areas with less stringent water quality standards. As a result some standards were lowered. Fayetteville provided monetary assistance to upgrade Campbell Soup’s water pretreatment, as one solution to pollution in the White River. In Huntsville, Butterball treated about one million gallons of wastewater with chemicals daily in two open lagoons (ponds) before sending it to the town’s water-treatment plant. But the fat and meat remnants in the water caused a stink, forcing Butterball to build a 1.7-million-gallon storage tank in 2018 to pretreat its wastewater.

“You can’t often see the pollution itself, but you can see the result. When the water becomes overloaded with nutrients algae begins to grow wildly as do some other aquatic plants. This wild growth deprives the water of necessary oxygen. If the situation persists the result is scummy green water, dead fish and plants, evil smells, and so forth.”

Joe Neal

Grapevine, September 6, 1978

Photo Gallery

90-24-30

Eggbreakers at Jerpe Dairy Products, Fayetteville, December 1942. Washington County History Book Collection (S-90-24-30)

77-9-329

Mr. and Mrs. C. H. Phillips, Springdale, 1950s-1960s. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-77-9-329)

SN-5-7-1966

7th annual Northwest Arkansas Poultry Festival, Springdale, May 7, 1966. Jim Morriss, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 5-7-1966)

2003-2-1120

Springdale Electric Hatchery, 1930s. Washington County History Book Collection (S-2003-2-1120)

2002-72-168A

Gail Brown with a LedBrest Cockerel, Springdale, July 1961. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-168A)

2006-129-79

Chicken catcher, Springdale, January 1964. Earlene Brown Henry Collection (S-2006-129-79)

2015-33-6

William Patrick (left) and Benjamin “Pat” Patrick at Pat’s Hatchery, Springdale, 1950s–1960s. Rosemary Patrick Hash Collection (S-2015-33-6)

93-84-69

Joe Steele and Shelby Ford at First State Bank, Springdale, 1960s–1970s. Bruce Vaughan, photographer. Bruce Vaughan Collection (S-93-84-69)

77-9-195

George’s Inc. feed mill, Springdale, 1950s. Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-77-9-195)

2006-129-45

Chicks in a brooder room at Jeff D. Brown and Son Co., Springdale, January 1964. Earlene Brown Henry Collection (S-2006-129-45)

2001-82-272

Boy carrying eggs at J. J. Arthurs’ farm, Springdale, September 1959. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-272)

2002-72-30

Jerry Hinshaw teaching at a school for poultry growers at Arbor Acres, Springdale, July 1961. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-73-30)

85-14-17

Shipping poultry to New York from Burt Snow Produce, Carroll County, 1910s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-14-17)

99-125-1

Packaging chicken at Springdale Farms, Springdale, late 1950s. Guy Loyd, photographer. Lois J. Loyd Collection (S-99-125-1)

86-122-37

Live birds hung for processing at Swift Company, Huntsville, 1974. Beatrice Foods Collection (S-86-122-37)

Credits

AgResearch Magazine. “Alum Curbs Phosphorus Runoff and More.” United States Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, 11/2006. (accessed 11/2020)

Arkansas Agriculturalist. “Broiler Production In Northwest Arkansas.” Vol. 28, No. 7 (March 1951).

Behar, Richard. “Arkansas Pecking Order.” Time, 10-26-1992.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. “Cargill recalls ground turkey tied to illnesses.” 8-4-1011.

Arkansas Poultry Times. “45 Years in Poultry Industry.” 10-29-1976.

———.“’Mr. Chicken Banker’ Honored By Poultry Industry In Six States.” 10-4-1961.

———. “New Brooder Houses Are All O.K.” 4-2-1976.

———. “Seymour Foods, Springdale, Holds Open House.” 7-15-1970.

Arkansas Poultry News. “They Said It Couldn’t Be Done in 1936 When He Started in Turkeys.” 1-15-1964.

Blagg, Brenda. “Tyson Expects Poultry to Become Nation’s Best Seller.” Springdale News, 2-21-1988.

Bowers, Rodney. “$50,000 ‘Lean Laying Machines’ Give 60 Million Eggs a Year for Lincoln Farmer.” Southwest Times Record, 4-13-1984.

Bowman, Maxine. “Jeff Brown, Broiler Pioneer, Started At 10 Nursing Sick Hens in Backyard.” Southwest Times Record, 3-14-1954.

Brown, Jeff D. Biography written for the Chicken-of Tomorrow Association, 3-1951.

Cable, C. Curtis Jr. Growth of the Arkansas Broiler Industry. Bulletin 520, Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arkansas College of Agriculture: Fayetteville, 4-1952.

Cox, Virginia. “Brand Rex to now be known as ESSEX.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 3-22-1990.

Crisp, Huey. Lloyd Peterson and Peterson Industries: An American Story. August House: Little Rock, 1989.

Davis, Daphne. “UA strives for ‘chicken of the future.’” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

Doran, Bill. “New Springdale Farms Plant Ranks With Finest in Nation.” Poultry & Eggs Weekly, 11-1-1958.

Ebner, Nina et al. Wages and Working Conditions in Arkansas Poultry Plants. Northwest Arkansas Workers’ Justice Center, 1-2-2016.

Elsey, Jenny. “Chicken business fine for Certain.” Prairie Grove Enterprise, 12-19-1985.

Farmer, Fayrene. “Poultry industry ‘thriving’ in Green Forest in 1938.” Green Forest Tribune, 11-8-1995.

Fayetteville Daily Democrat. “Few Will Eat Turkey This Thanksgiving.” 11-22-1922.

Fincher, Amanda. “Poultry plant foreman looks for the ‘edges.’” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

———. “Shipping methods have changed.” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

Flanagin, Scott. “All Wright.” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

———. “The egg comes first at hatcheries.” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

———. “Infamous poultry case is finally going to get an ending.” Food Safety News, 3-5-2020. (accessed 12/2020)

Francoeur, Mark. “Breaking Millions of Eggs A Week Routine at Monark.” Springdale News, 2-21-1988.

Garrett, Rusty. “A veterinarian for the masses.” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

———. “To Market: What do they do with what we don’t eat?” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

Golden, Alex. “CDC recommends plan for virus in state’s Northwest.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 7-20-2020.

Harrington, Rod. “Butterball to reduce lagoon use.” Madison County Record, 9-6-1918.

Hull, Clifton E. “Apple Orchard Disease Gave Birth to Broiler Industry.” Arkansas Gazette, 3-29-1970.

Havel, O’Dette. “Contest Was No Cockamamie Notion.” University Reflections, Spring 1993.

The Humane Society of the United States. “An HSUS Report: The Welfare of Animals in the Egg Industry.” 2007. (accessed 12/2020)

Irvin, David. “Farming like St. Francis.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 1-13-2008.

Jessen, Janelle. “Decatur company has begun hatching free-range chicken.” Westside Eagle Observer, 1-8-2014.

Jines, Billie. “Springdale Family Develops Successful Poultry Processing Plant In Connection With Thriving Broiler Farm Near City.” Springdale News, 10-23-1951.

Johnson, Don. “Northwest Passage: Report on a Cultural Change.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 3-23-1997.

———. [incomplete headline] “….sends tremors through Northwest Arkansas life.” (Part 1 of a 4-part series: “Northwest Passage: Report on a Cultural Change.”) Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 3-23-1997.

Kennedy, Steele T. “Berryville Reigns as ‘Turkey Capital of Arkansas.’” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 5, No. 2 (11/1956).

———. “Berryville—The Heart of the Mammoth Ozarks Turkey Industry.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 5, No. 3 (12/1956).

King, Laura. “INS Continues Raids in Rogers, 100 Arrested as Illegal Aliens.” Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, 9-20-1995.

Kuettner, Al. “The Peterson Story’s New Look.” Gravette News Herald, 9-16-1987.

Leonard, Christopher. “Boutique farms.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 8-29-2004.

Madison County Record. “Turkeys Shipped By Thousands From County.” 11-14-1929.

Martin, Rita. “Technology makes poultry raising easier.” Northwest Arkansas Business Times, 2-13-1995.

McWilliams, James. “The Lucrative Art of Chicken Sexing.” Pacific Standard, 9-8-2018. (accessed 11/2020)

Medders, Howell. “UA Research Programs Support Agriculture.” Springdale News, 4-21-1985.

Monroe, Jill. “Hispanic Immigration in Arkansas.” Honors paper, Henderson State University, 1999. (accessed 12/2020)

Morning News of Northwest Arkansas. “Arkansas Quality Found in Roy Ritter’s Poultry Farms, AQ Chicken House.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Bob Sharp’s Innovations Fuel Industry.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Future of Canning, Poultry, Beaver Lake Preserved by Cousins.” 4-21-1991.

———. “George Builds Business in Poultry, Cattle.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Jeff Brown Hatches New Ideas in Poultry.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Joe Robinson Kept Poultry Hauling Lively.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Loyd ‘Family’ Builds Successful Processing Plants for Just Plucked Poultry.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Poultry industry hatches economic boom for state.” 8-24-1997.

———. “Shelby Ford Banks on Poultry Industry.” 4-21-1991.

———. “Tough Times Don’t Stop Tyson Family.” 4-21-1991.

Neal, Joe. “Arkansas Poultry Skyline.” Manuscript for Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. 5-8-1986.

———. “Downstream from the Chicken Houses: Some Environmental Considerations for the Arkansas Poultry Industry,” (part III). Grapevine, 9-6-1978.

Newcomb, Kelby. “Best-laid plans: An easy overview of BV’s new egg processing plant.” Carroll County News, 5-3-2016.

Newsweek. “A Town’s Two Faces.” 6-3-2001. (accessed 12/2020)

Niese, Jeff. “Regulations, Land Price Hurdles.” Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, 10-12-2003.