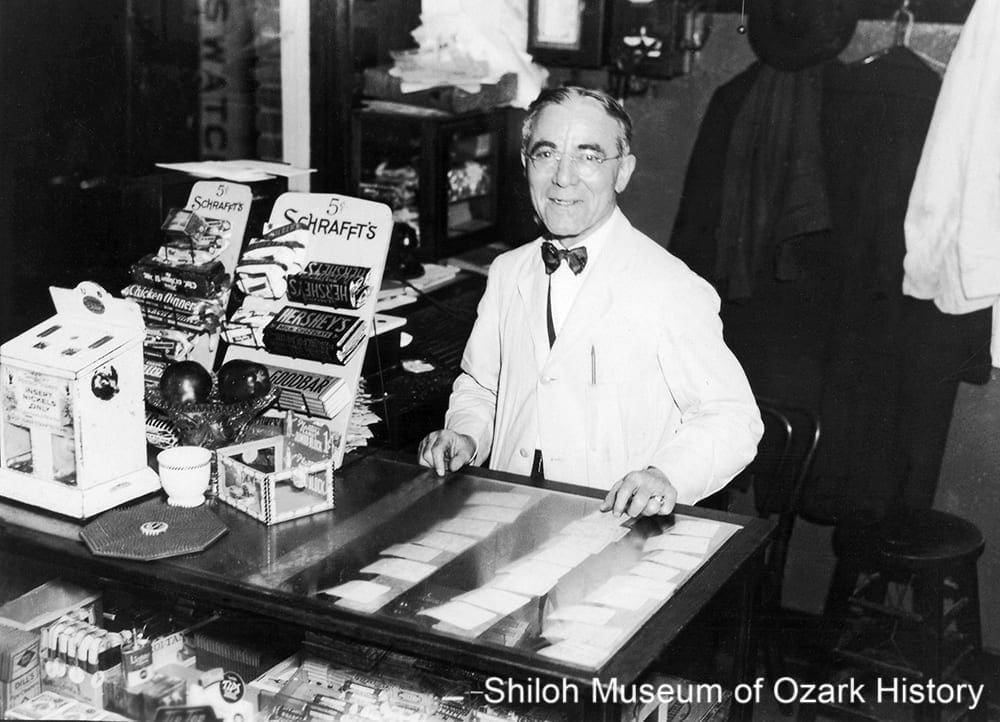

George Pappas at the counter of the Majestic Café, Dickson Street, Fayetteville, 1930s. Fran Deane Alexander Collection (S-2012-137-557)

The family joke is that when the first Greeks immigrated to the U.S. they had one of three occupations—restaurateur, confectioner, and cobbler. My paternal grandfather had a soda fountain and candy kitchen before switching to shoe shine and repair. In 1907 he immigrated from the Peloponnese (a peninsula in southern Greece) and settled in Chicago, home to a large Greek community. When I moved to Northwest Arkansas many years ago and began working in museums, I was surprised to find that several Greek men had made their home here in the early 1900s.

As I dug deeper into their stories I was able to see how their history, and that of my grandfather, mirrored the greater Greek migration. Around the turn of the 20th century nearly 90% of Greek immigrants were men. Many came with the intention of earning enough money to return home with capital for themselves and, more importantly, dowries for sisters and daughters. But continued conflict in Greece, loss of homeland, the forced return to Greece of a large number of Greeks from Asia Minor, and changing U.S. immigration policies left many stranded. While some married non-Greek women, many remained bachelors, just like the elderly honorary “uncles” in my family.

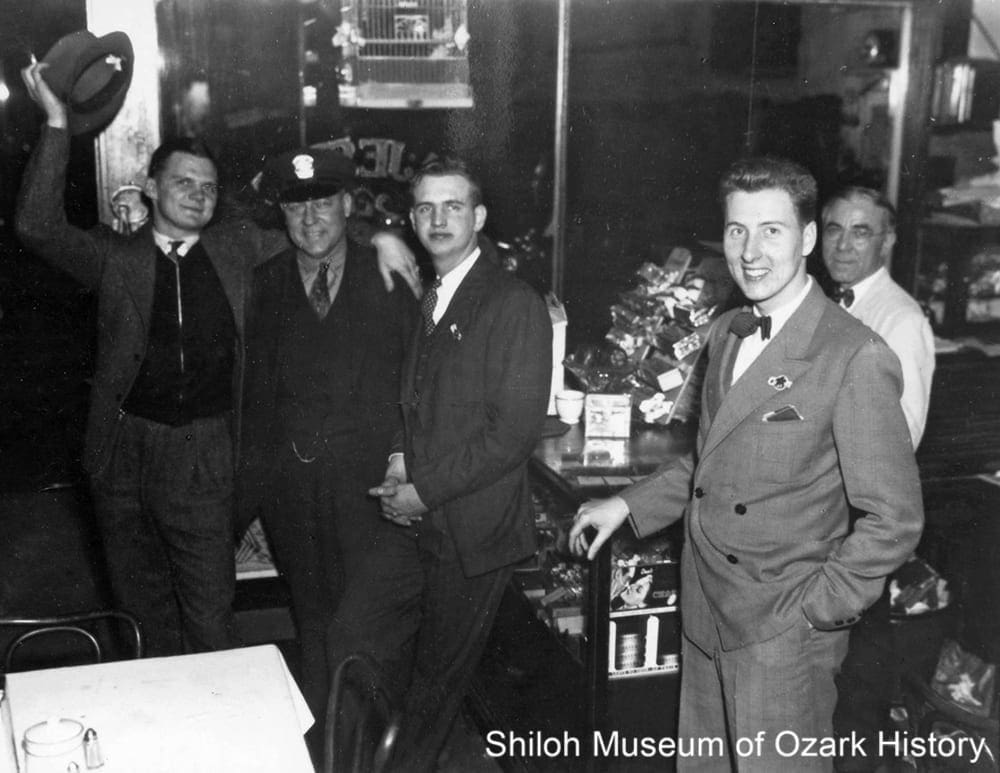

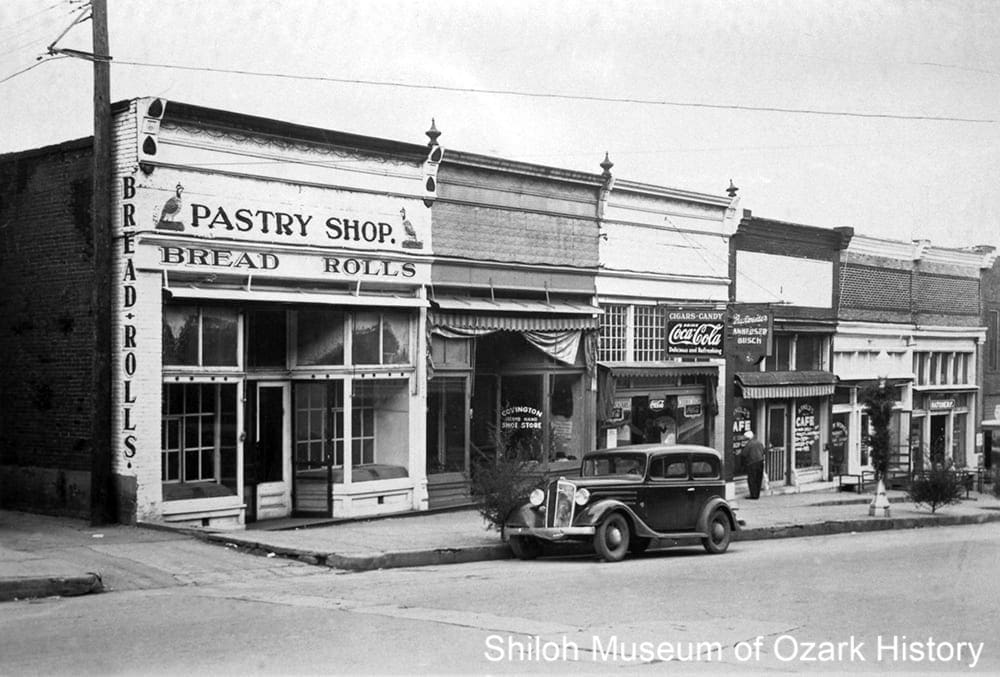

George Pappas (far right) at the Majestic Café, Dickson Street, Fayetteville, 1930s. With University of Arkansas students and Fayetteville patrolman, Theo Burns. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-805)

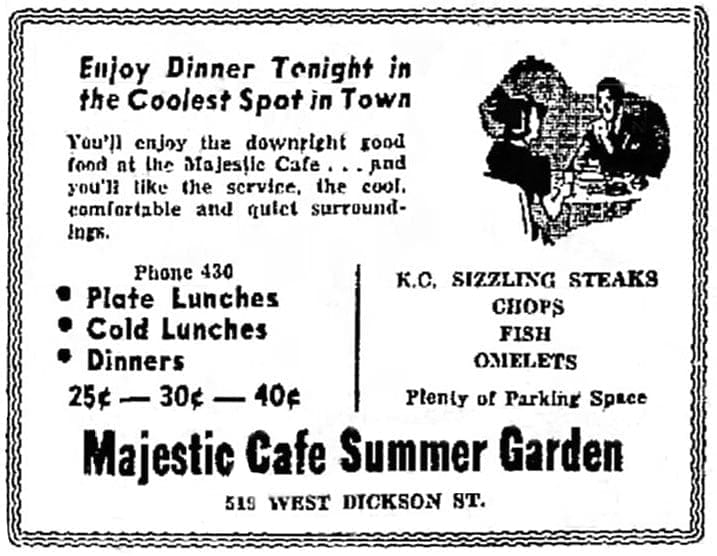

The first Greek I heard about was George Stavrou Pappas [originally Papadapoulos] (1881-1966). He may have been born in Athens and from there moved to Egypt and then to New York and St. Louis before heading to Fort Smith, Arkansas. There he ran the Manhattan Café for twenty or so years, from the 1910s to the 1920s. In 1927 he opened the Majestic Café on Dickson Street in Fayetteville, not far from the campus of the University of Arkansas. The café was frequented by faculty, students, businessmen, Frisco workers, and tourists. George called in lunchtime customers by standing on the street and ringing a large metal triangle. The café was a bit of a convenience store, too, selling such things as candy, cigars, and soap. In 1938 a “summer garden” was built for outdoor dining, with beer served under a grapevine arbor. During World War II George burned the hot checks he held from students heading to war, saying “his boys” owed him nothing.

George’s brother John Pappas (1877-1953) was a sailor before he became chief cook at the café. He served a variety of dishes including steaks, sandwiches, chicken tamales with chili, squab, fish, omelets, split pea soup, fresh shrimp and oysters, and “mountain oysters” (bull testicles). According to journalism professor Walter J. Lemke, professor and future U.S. senator J. William Fulbright often had lunch at the café, but he “distrusted the highly seasoned Greek dishes and always ordered Campbell’s tomato soup, out of a can.” The rationing of meat supplies in 1945 hit the restaurant hard. Before World War II it sold an average of “400 high grade steaks every Saturday and Sunday.” The cut in supplies was projected to bring the number down to ten or fifteen steaks a weekend. John stayed connected with his homeland. In October 1950 he wrote an article for the Northwest Arkansas Times which advocated for the return of the island of Cyprus, then under British rule, back to Greece. The paper’s publisher and editor was Roberta Fulbright (J. William’s mother), who counted “Fayetteville’s Greeks” amongst her friends.

The Pappas brothers had two cousins who worked at the café for a time. Theodore “Theo” H. Kantas (born circa 1890) was the head waiter. He helped George with the Fort Smith café, too. Nick Kabouris [sometimes spelled Kambouris] (circa 1896-1951) was born in Athens and came to the U.S. as a young man. In 1930 he may have worked in a sandwich shop in Seminole, Oklahoma (near Oklahoma City). Back then Seminole had sixteen restaurants owned by Greeks, and it was said that “the Greeks feed the oil fields.” He was living in Fayetteville at least by 1932, where he rented a room at the Washington Hotel and worked at the Peoples Café, both on the square. Following Italy’s attack on Greece in 1940 during World War II, several prominent Greek Americans created the national Greek War Relief Association. Nick served as a local division chairman, raising money to aid relief efforts.

Denny Malloy [originally Mallas] (1894-1973) was born on the Ionian island of Zakynthos. Before serving in the U.S. Army during World War I he worked as a street paver in Sioux City, Iowa. He married Anna Selby in 1928. By 1942 the couple lived in Rogers where he was often away during the summer working as a highway concrete finisher. They did not have children.

Anastacious Thomas “Tom” Mulos [originally Mullos], (1890-1965) was born in Kithira, an island off of the southern tip of the Peloponnese. In 2005 his daughter-in-law shared the family’s history with the Rogers Historical Museum. According to Clara Lee Mulos, Tom came to the U.S. in 1905 to seek a better life, not telling his mother that he was leaving Greece until the morning his ship sailed. He traveled to St. Louis to stay with a relative and it was there where he learned to make candy. In 1914 he moved to Rogers and opened the Rogers Candy Kitchen on Walnut Street (later moving the business to Second Street, across from the Victory Theatre). He served in the army during World War I. In 1921 he married Eunice Phillips, one of his employees. They had one child and, as a family, attended a Baptist church. While they didn’t follow Greek traditions, they did eat some Greek food. The store had homemade candy, a soda fountain, and an ice cream bar featuring such flavors as vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. Clara’s favorite was the pineapple sherbet. For a time Tom supplied ice cream to the Sunset Hotel at the Linebarger brothers’ summer resort in Bella Vista. The store closed after forty-four years in business, after Tom’s heart attack in 1958.

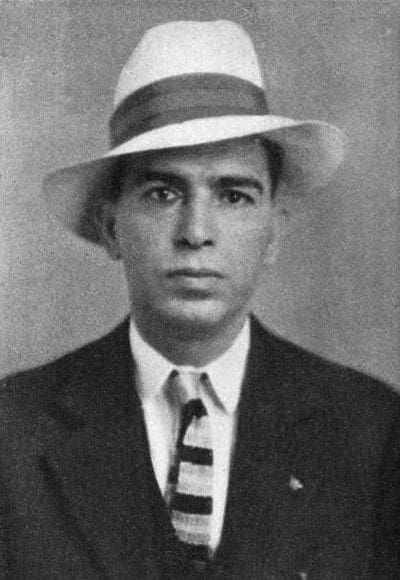

Ted Logus, as depicted in the January 1928 edition of the Rotarian.

Theodore “Ted” Logus [originally Logothetis] (1882-1966) was born in the Ionian Islands on the western side of Greece. He came to the U.S. around 1904 and went to St. Louis to learn candy-making from an uncle. While there he ran a marathon in his street clothes (rather than athletic gear); he came in fifth place. By 1911 he was co-owner of the Neosho Candy Kitchen in Missouri. That’s where he married Maunte Caughron in 1913. A year later the couple lived in Rogers, where Ted co-owned the Rogers Candy Kitchen with Tom Mulos. During World War I he worked on behalf of the War Industries Board to secure “data as to all the available walnut timber” around Rogers for use in airplane construction. After the war he was one of several businessmen who helped organize a town band. He was a Mason and a charter member of the Rogers Rotary Club. For a short time he co-owned the U.A. Candy Kitchen in Fayetteville with Steve Georgenis. In 1930 he had a soda fountain, coffee shop, and confectionary at the lakeside pavilion in Bella Vista. Realizing there wasn’t enough business in Rogers during the Great Depression, he gave his share of the Rogers store to Tom, who had a wife and young son to support. As a divorcee with an adult daughter, Ted figured he could earn a living elsewhere. The Mulos’ repaid this kindness in Ted’s later years, making sure he had home-cooked food and medical care.

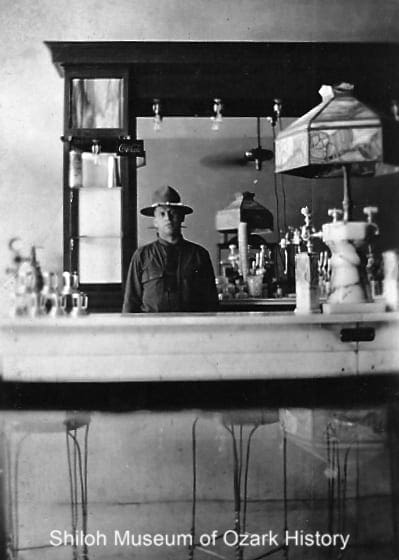

Private Steve Georgenis behind the soda fountain of his candy kitchen, Fayetteville, mid-late 1910s. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-55-797)

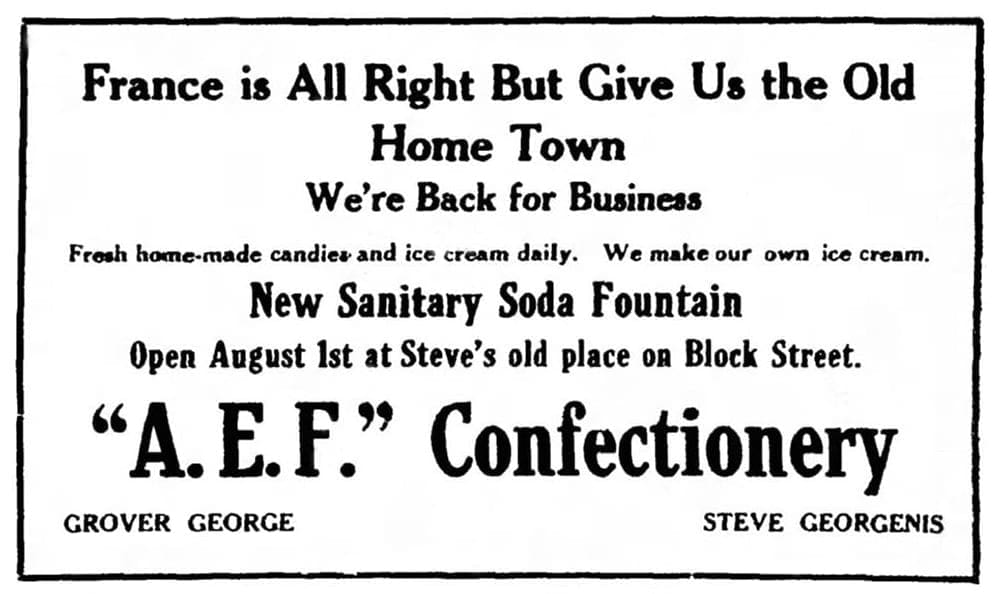

Stamatis “Steve” G. Georgenis (about 1885-1934) was born in Smyrna, Asia Minor (then heavily settled by Greeks, now part of Turkey). He came to the U.S. in 1912 and settled in Fayetteville two years later. Over the years he owned or co-owned candy kitchens on Block Avenue and Dickson Street, under the names of Palace of Sweets, “A.E.F.” Confectionary, U. of A. Candy Kitchen, and Steve’s Place. He sold homemade ice cream, sherbet, and candy along with salted peanuts, soda-fountain drinks, coconut brittle, taffy, banana splits, and cantaloupe sundaes.

Steve Georgenis’ candy kitchen, third storefront from the left, North Block Avenue, Fayetteville, about 1934. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-75)

Ann Wiggans Sugg, whose family owned the Block Avenue storefront, remembers that “Uncle Steve” gave her candy whenever she went to the store. During the holidays he often treated children to Easter eggs and candy canes. In 1927 he received word that he and his eleven brothers were heir to 1.5 million dollars from their grandfather’s estate in Constantinople, Turkey. He traveled there to collect his share but as to the outcome, no information could be found. He was a member of the local unit of the Arkansas National Guard, serving on the Mexican border in 1916 and later as a cook during World War I. When asked about his service he said, “A country that’s good enough to live in is good enough to fight for.” A founding member of the Lynn Shelton Post of the American Legion, Steve was buried in Fayetteville’s National Cemetery with full honors, including a firing squad of eight uniformed Guardsmen and a bugler sounding “Taps.” Following Steve’s death, Ted Logus ran his shop on Block Avenue until the summer of 1937.

“A.E.F.” Confectionary ad, Fayetteville Daily Democrat, July 28, 1919. The name refers to the American Expeditionary Forces, a unit of the U.S. Army formed to fight on the Western Front (largely in France) during World War I. At the time of this ad, proprietor Steve Georgenis had just returned from serving overseas.

One of the pallbearers at Steve’s funeral was Louis J. Lagos (circa 1896-1958). Possibly born in Sparta in the southern Peloponnese, he was a small boy when he came to America, first living in Ohio and then Chicago. In Oklahoma he operated a candy store in Oklahoma City and had cafes in Seminole and Tulsa. He served in World War I and was a member of the American Legion and the Masons. While the 1940 census shows him a resident of Tulsa, his “inferred residence in 1935” is Fayetteville.

James Vafakos, Indiana Harbor, Indiana, 1910s. J. F. Atlas, photographer. Courtesy William N. Vafakos

Dimitrios “James” Nick Vafakos (1885-1975) was born in Arna, a village in the southern Peloponnese. He arrived in New York in 1903. He served during World War I and, prior to that, was said to have helped chase Mexican bandit Pancho Villa. For a time he homestead land in Crawford County, where he married Hazel Cranley in 1922. The couple had two sons, one of which is William, who recently shared his father’s history with the museum. Because James was disabled due to a gas attack during the war, he was unable to work. The family moved to a farm near Prairie Grove where they lived on home-grown vegetables, livestock, and James’ military pension. He also had a vineyard of Concord grapes. Although Washington County was “dry” for a time (no alcohol could be purchased), James received a permit to make wine at home, as long as he didn’t sell it. William doesn’t remember the family eating Greek food or celebrating that county’s traditions. The only times his dad spoke Greek was to the cows when he got mad, or to his friend, Jimmy Anagnost, when the two didn’t want their wives to hear what they were talking about.

Gust James “Jimmy” Anagnost [originally Anagnostopoulos] (1888-1959) was born in Trikala, in mainland Greece. He arrived in the U.S. in 1905. After coastal-defense service in World War I he homesteaded in Crawford County, later moving to Washington County with his friend, James Vafakos. It’s possible that the two of them hunted gold and silver in the Prairie Grove area, as James’ son, William, found old assayer reports stating that the minerals were detected, but not in enough quantity to make extraction profitable. Jimmy married Dora Hart in 1926 and together they had four children. An electrician, he worked several odd jobs including hauling goods in his truck and working on local Works Progress Administration projects during the Great Depression. During World War II he worked in the steel industry in Chicago, eventually earning enough money to move his family out of their old dog-trot log cabin and into a brand-new house near Strickler.

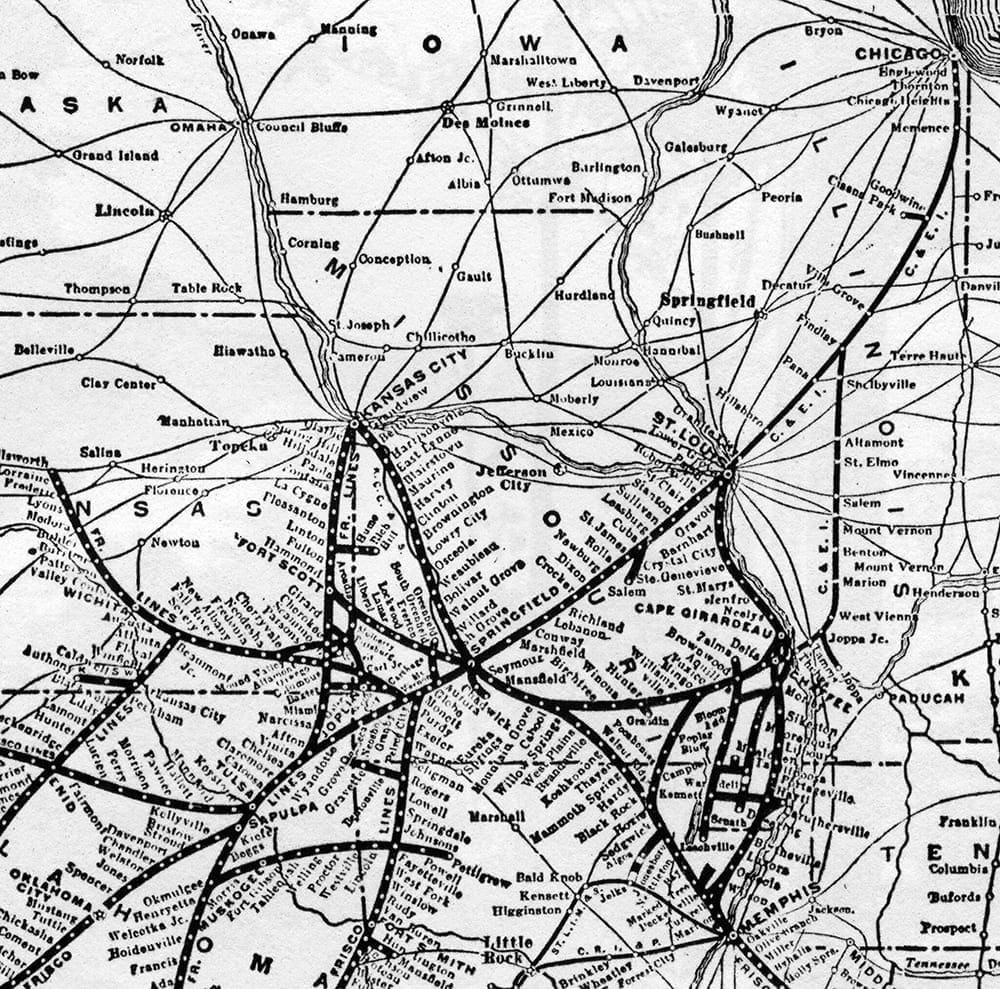

It’s clear that these men contributed to Benton and Washington counties in ways large and small. But why did they come to Northwest Arkansas? Here’s my guess. . . Connect the dots between St. Louis, Neosho, Rogers, Fayetteville, and Fort Smith and you have a section of the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad line. It would be so easy to move from one town to the next, looking for opportunities. Once here, the Greeks connected with one another, as friends and as businessmen. Ted partnered with Tom and Steve in candy kitchens and James regularly came to Fayetteville to visit the Pappas brothers. When Steve died, nearly all of the Greeks were active or honorary pallbearers at his funeral.

James Vafakos with the 1st Aero Observation Squadron, just back from France, August 1919. Courtesy William N. Vafakos

Most of the men connected to their newly adopted country by serving in some capacity during World War I. They established community connections as well, through friendships with town leaders and as members of fraternal, business, and military organizations. The Majestic Café even played a role in local government, serving as a polling place for Fayetteville’s Ward 4 voters. Although a few of the men maintained some connection to their homeland, either through food or political engagement, most adapted to their new country. Some even married American women. For the most part their children grew up American—they didn’t learn the language, eat the food, or follow the traditions of Greece.

Illustration from a chocolate and candy recipe booklet distributed by Walter Baker and Company, 1922. Courtesy Carolyn Reno

And the candy connection? Turns out it was a real phenomenon, not just a Demeroukas-family joke. In her 2014 dissertation, Greek Immigration To, and Settlement In, Central Illinois, 1880-1930, Ann Flesor Beck recounts that many Greek immigrants came from the Peloponnese, where they had had enough of regional conflict and hard-scrabble farming. In America they gravitated to urban areas, especially those with large Greek populations. As unskilled workers they joined railroad crews, like the Greeks who in 1902 worked on building the Ozark and Cherokee Central Railroad in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) from Westville to Tahlequah, just east of Washington County. They also pursued entrepreneurial endeavors with minimal start-up costs such as shining shoes or pedaling fruit. Some worked in or started their own restaurants, soda fountains, and candy kitchens. A 1904 article in the Greek Star newspaper declared Chicago “the Mecca of the candy business” and said that “practically every busy corner in Chicago is occupied by a Greek candy store.” Newly arrived Greek immigrants learned the business from their Greek employers before striking out on their own. Many found their way to St. Louis, where the town’s Greek population grew from roughly 1,300 in 1910 to an estimated 5,000 five years later. In 1915 one Greek newspaper estimated that there were about fifty thousand Greeks working in the confectionary business.

Rogers Candy Kitchen, owned by Tom Mulos, South Second Street, Rogers, 1950s. Courtesy Rogers Historical Museum

I wish I could go back in time and visit the candy kitchens to sample the treats made by Tom, Ted, and Steve. And after? I’d dine with the Pappas brothers at the Majestic Café. (Yeah, dessert first.) The closest I’ve come to spending time with George and John was in the early 1980s, when I hung out with my fellow anthropology students in the beer garden at George’s Majestic Lounge, a bar and music venue. I didn’t know it at the time, but in some way I was connecting with my Greek heritage. Opa!

Marie Demeroukas is the Shiloh Museum’s photo archivist and research librarian.

0 Comments