For the Fans

Tontitown Grapers baseball team at Mantegani Park in Tontitown, circa 1945. From left: Abe Pianalto, Virgil Verucchi Jr., Williard Moon, Paul Pianalto, Bill Fiori, Guy Bariola. Veronica Keith Collection (S-2006-44-5)

A couple years ago I went to my first-ever minor league professional baseball game. It immediately began a love affair that I thought might wane, but it really has not. I went to my first major league game last summer and loved every moment of it. Sadly, this year I have been watching replays of previous games and following players on Twitter and Instagram. We will not discuss the teams (nor sports, nor players) I follow because I understand just how passionate people are about their favorites, but the experience reminds me of an article I read as an undergrad about baseball magic and the incredibly dedicated and detailed rituals players and fans engage in to ensure a win. Next time you watch a basketball player take a free-throw or a pitcher set up, watch for their routine. You won’t be able to unsee it once you find it.

A while back, museum outreach coordinator Susan Young proposed that Aaron Loehndorf (the museum’s collections/education specialist and arguably the biggest baseball fan among the museum staff) and I come up with an “Shiloh Sandwiched-In” program on a local sports topic. Before we agreed to the idea, we wanted to be sure enough material was available to put a program together. Of course there was. Our research focused on the most common form of baseball magic—mascots. Ultimately the Sandwiched-In talk was sidelined and the research went into files on my external hard drive. But the topic stayed in the back of my mind for a long time. If I came across a new team while I was working on something else, I made a note or took a picture with my phone and added the information to my spreadsheet. And then it just sat there. Until now.

Tontitown Grapers baseball team at Mantegani Park in Tontitown, circa 1945. From left: Abe Pianalto, Virgil Verucchi Jr., Williard Moon, Paul Pianalto, Bill Fiori, Guy Bariola. Veronica Keith Collection (S-2006-44-5)

A couple years ago I went to my first-ever minor league professional baseball game. It immediately began a love affair that I thought might wane, but it really has not. I went to my first major league game last summer and loved every moment of it. Sadly, this year I have been watching replays of previous games and following players on Twitter and Instagram. We will not discuss the teams (nor sports, nor players) I follow because I understand just how passionate people are about their favorites, but the experience reminds me of an article I read as an undergrad about baseball magic and the incredibly dedicated and detailed rituals players and fans engage in to ensure a win. Next time you watch a basketball player take a free-throw or a pitcher set up, watch for their routine. You won’t be able to unsee it once you find it.

A while back, museum outreach coordinator Susan Young proposed that Aaron Loehndorf (the museum’s collections/education specialist and arguably the biggest baseball fan among the museum staff) and I come up with an “Shiloh Sandwiched-In” program on a local sports topic. Before we agreed to the idea, we wanted to be sure enough material was available to put a program together. Of course there was. Our research focused on the most common form of baseball magic—mascots. Ultimately the Sandwiched-In talk was sidelined and the research went into files on my external hard drive. But the topic stayed in the back of my mind for a long time. If I came across a new team while I was working on something else, I made a note or took a picture with my phone and added the information to my spreadsheet. And then it just sat there. Until now.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word mascot as “a person or thing that is supposed to bring good luck; (now) esp. something carried or displayed for this purpose. Also: a thing (often an animal or personified character) used by an organization, esp. a sports team, as a symbol or for good luck; an emblem.” The origin of the word is French and first appeared in 1867 in an operetta by Edmond Audran. (This operetta was first performed in 1880, if you would like to know.)

Mascots have evolved in many ways. Early mascots for baseball, for example, were young boys who sat with the team. Now they can be Mudhens, Celery Stalks, or Gus the Pioneer (Gentry Public Schools, Benton County.) Mascots provide entertainment and encourage engagement with the crowds. They dance, they interact directly with fans, and often have a ritual of their own their team scores. Mascots have even been controversial, most recently with teams using Native American nomenclature. And what if your team has the same mascot as another? Ahem, Fayetteville and Springdale: both towns have used the Bulldog as their mascot for decades. This sparked a friendly rivalry and newspaper accounts differentiated by calling them by the team color (purple for Fayetteville, red for Springdale) rather than Bulldogs when they published a retelling of games between the two teams.

Siloam Springs football team, 1928. Front row, from left: Chester Gilliland, Roy Wolfe, “Tiny” Ward, Zeke Cecil Camp, Vaul Smith, Cal Dean Gunter Jr., Peter “Taz” Paul LaFallette. Back row, from left: Paul “Dayo” Guthrie, Ralph “Slick” Henry, Lee “Athletic” Elrod, Cecil “Beardie” Elrod. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-297-69)

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word mascot as “a person or thing that is supposed to bring good luck; (now) esp. something carried or displayed for this purpose. Also: a thing (often an animal or personified character) used by an organization, esp. a sports team, as a symbol or for good luck; an emblem.” The origin of the word is French and first appeared in 1867 in an operetta by Edmond Audran. (This operetta was first performed in 1880, if you would like to know.)

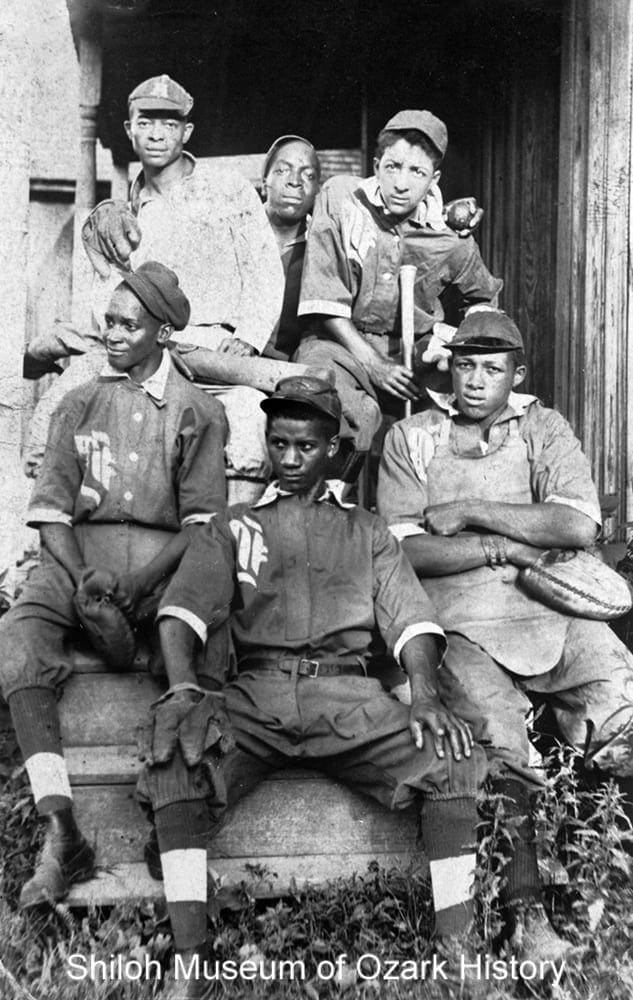

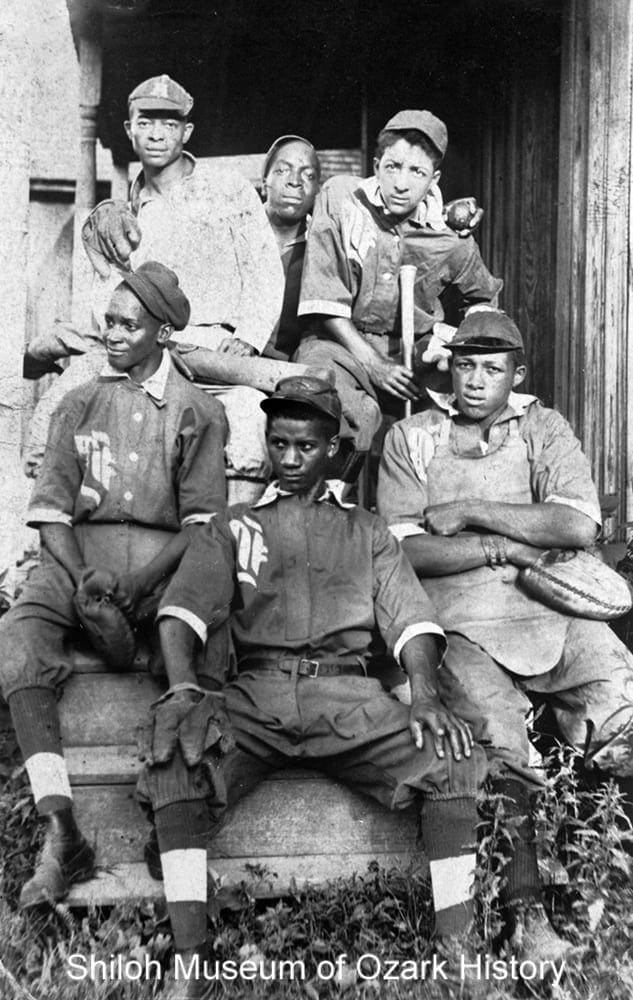

Bentonville baseball team, circa 1912. The team was part of a regional African-American league ranging from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Joplin, Missouri. Back, from left: Thad Wayne, Marion “Sonny” Finney, and Lloyd Trout. Front, from left: Yates Claypool, Virge Black, and John Barker. Elizabeth Robertson Collection (S-95-7-42)

Mascots have evolved in many ways. Early mascots for baseball, for example, were young boys who sat with the team. Now they can be Mudhens, Celery Stalks, or Gus the Pioneer (Gentry Public Schools, Benton County.) Mascots provide entertainment and encourage engagement with the crowds. They dance, they interact directly with fans, and often have a ritual of their own their team scores. Mascots have even been controversial, most recently with teams using Native American nomenclature. And what if your team has the same mascot as another? Ahem, Fayetteville and Springdale: both towns have used the Bulldog as their mascot for decades. This sparked a friendly rivalry and newspaper accounts differentiated by calling them by the team color (purple for Fayetteville, red for Springdale) rather than Bulldogs when they published a retelling of games between the two teams.

It is not just the mascot that evolved, but the sports and organizations themselves. Over the years, we’ve had our school teams of course, but we also had town teams that would sometimes take on the school team. On July 30, 1937, the Fayetteville Daily Democrat reported on the local WPA baseball league: Greenland beat Tontitown, and Springdale was scheduled to play Fayetteville the following day. We also had professional teams that might play for a season or two and then disappear. These pro teams were funded by local businessmen. And one of the most important changes to sports was desegregation of teams and leagues.

Lest you think I refer to baseball mascots only, I would like to report that on July 14, 1967, the Springdale News recounted a football game between the local police department (the Fuzz) and the fire department (the Hose Jockeys).

Some sports played on the local level were obscure, or so I thought. Does anyone know what shinskinner hockey is? I found this mentioned in one article from 1929. When I did some initial Google-searching I came up with the Bruins. These guys are hockey players today, but once upon a time, there was a soccer team called the Bruins. But in this instance? Basketball, boys and girls. Shinskinner hockey referred to basketball.

Below is the data I have collected thus far, with a lot of help from Aaron. I hope you enjoy exploring the variety of mascots Northwest Arkansas has seen over the years!

COUNTY | SCHOOL | MASCOT |

Benton | Bentonville | Tigers |

Benton | Decatur | Bulldogs |

Benton | Gentry | Pioneers; was Gorillas (football) |

Benton | Gentry (may be club team) | All-Stars (baseball) |

Benton | Gentry | Longhorns (basketball) |

Benton | Gravette | Lions |

Benton | Gravette (town team) | Blues (baseball) |

Benton | Ozark Adventist Academy | Skeeter the Skyhawk |

Benton | Pea Ridge | Blackhawks |

Benton | Rogers Heritage High | War Eagles |

Benton | Rogers High | Mounties, was Mountaineers |

Benton | School of the Arts | Penguins |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Panthers, was Travelers (baseball) |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Bear Cats (town baseball team) |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Jays (town baseball team) |

Benton | Siloam Springs Northside Elementary | Koalas |

Benton | Sulphur Springs | Pirates |

Boone | Alpena | Leopards |

Boone | Bergman | Panthers |

Boone | Everton/Bruno-Pyatt | Patriots |

Boone | Gaither | Cubs |

Boone | Harrison | Golden Goblins |

Boone | Lead Hill | Tigers |

Boone | Omaha | Eagles |

Boone | Valley Springs | Tigers |

Carroll | Berryville | Bobcats |

Carroll | Eureka Springs | Highlanders |

Carroll | Green Forest | Tigers |

Madison | Huntsville | Eagles |

Madison | Kingston | Yellowjackets |

Madison | St. Paul | Hornets |

Newton | Deer | Deer |

Newton | Jasper | Pirates |

Newton | Mount Judea | Eagles |

Newton | Western Grove | Warriors |

Washington | Elkins | Elks |

Washington | Farmington | Cardinals |

Washington | Fayetteville | Purple Bulldogs |

Washington | Fayetteville | Maulers (junior football, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Pirates (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Rinkydinks (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Little Can (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Caddies (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Educators; became Angels (town minor league baseball) |

Washington | Fayetteville Christian | Eagles |

Washington | Greenland | Pirates |

Washington | Haas Hall | Mastiffs |

Washington | Har-Ber | Wildcats |

Washington | Lincoln | Wolves |

Washington | Prairie Grove | Tigers |

Washington | Shiloh Christian | Saints |

Washington | Southwest Junior | Cougars |

Washington | Springdale | Red Bulldogs |

Washington | Springdale Police Dept. | Fuzz (football, 1987) |

Washington | Springdale Fire Dept. | Hose Jockeys (football, 1987) |

Washington | Tontitown | Grapers |

Washington | University High | Cardinals (basketball, 1929) |

Washington | West Fork | Tigers |

Washington | Winslow | Squirrels |

Washington | Winslow | Independents (basketball, 1929) |

Rachel Whitaker is the Shiloh Museum’s research specialist.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word mascot as “a person or thing that is supposed to bring good luck; (now) esp. something carried or displayed for this purpose. Also: a thing (often an animal or personified character) used by an organization, esp. a sports team, as a symbol or for good luck; an emblem.” The origin of the word is French and first appeared in 1867 in an operetta by Edmond Audran. (This operetta was first performed in 1880, if you would like to know.)

Bentonville baseball team, circa 1912. The team was part of a regional African-American league ranging from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Joplin, Missouri. Back, from left: Thad Wayne, Marion “Sonny” Finney, and Lloyd Trout. Front, from left: Yates Claypool, Virge Black, and John Barker. Elizabeth Robertson Collection (S-95-7-42)

Mascots have evolved in many ways. Early mascots for baseball, for example, were young boys who sat with the team. Now they can be Mudhens, Celery Stalks, or Gus the Pioneer (Gentry Public Schools, Benton County.) Mascots provide entertainment and encourage engagement with the crowds. They dance, they interact directly with fans, and often have a ritual of their own their team scores. Mascots have even been controversial, most recently with teams using Native American nomenclature. And what if your team has the same mascot as another? Ahem, Fayetteville and Springdale: both towns have used the Bulldog as their mascot for decades. This sparked a friendly rivalry and newspaper accounts differentiated by calling them by the team color (purple for Fayetteville, red for Springdale) rather than Bulldogs when they published a retelling of games between the two teams.

It is not just the mascot that evolved, but the sports and organizations themselves. Over the years, we’ve had our school teams of course, but we also had town teams that would sometimes take on the school team. On July 30, 1937, the Fayetteville Daily Democrat reported on the local WPA baseball league: Greenland beat Tontitown, and Springdale was scheduled to play Fayetteville the following day. We also had professional teams that might play for a season or two and then disappear. These pro teams were funded by local businessmen. And one of the most important changes to sports was desegregation of teams and leagues.

Lest you think I refer to baseball mascots only, I would like to report that on July 14, 1967, the Springdale News recounted a football game between the local police department (the Fuzz) and the fire department (the Hose Jockeys).

Some sports played on the local level were obscure, or so I thought. Does anyone know what shinskinner hockey is? I found this mentioned in one article from 1929. When I did some initial Google-searching I came up with the Bruins. These guys are hockey players today, but once upon a time, there was a soccer team called the Bruins. But in this instance? Basketball, boys and girls. Shinskinner hockey referred to basketball.

Below is the data I have collected thus far, with a lot of help from Aaron. I hope you enjoy exploring the variety of mascots Northwest Arkansas has seen over the years!

COUNTY | SCHOOL | MASCOT |

Benton | Bentonville | Tigers |

Benton | Decatur | Bulldogs |

Benton | Gentry | Pioneers; was Gorillas (football) |

Benton | Gentry (may be club team) | All-Stars (baseball) |

Benton | Gentry | Longhorns (basketball) |

Benton | Gravette | Lions |

Benton | Gravette (town team) | Blues (baseball) |

Benton | Ozark Adventist Academy | Skeeter the Skyhawk |

Benton | Pea Ridge | Blackhawks |

Benton | Rogers Heritage High | War Eagles |

Benton | Rogers High | Mounties, was Mountaineers |

Benton | School of the Arts | Penguins |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Panthers, was Travelers (baseball) |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Bear Cats (town baseball team) |

Benton | Siloam Springs | Jays (town baseball team) |

Benton | Siloam Springs Northside Elementary | Koalas |

Benton | Sulphur Springs | Pirates |

Boone | Alpena | Leopards |

Boone | Bergman | Panthers |

Boone | Everton/Bruno-Pyatt | Patriots |

Boone | Gaither | Cubs |

Boone | Harrison | Golden Goblins |

Boone | Lead Hill | Tigers |

Boone | Omaha | Eagles |

Boone | Valley Springs | Tigers |

Carroll | Berryville | Bobcats |

Carroll | Eureka Springs | Highlanders |

Carroll | Green Forest | Tigers |

Madison | Huntsville | Eagles |

Madison | Kingston | Yellowjackets |

Madison | St. Paul | Hornets |

Newton | Deer | Deer |

Newton | Jasper | Pirates |

Newton | Mount Judea | Eagles |

Newton | Western Grove | Warriors |

Washington | Elkins | Elks |

Washington | Farmington | Cardinals |

Washington | Fayetteville | Purple Bulldogs |

Washington | Fayetteville | Maulers (junior football, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Pirates (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Rinkydinks (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Little Can (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Caddies (junior basketball, 1929) |

Washington | Fayetteville | Educators; became Angels (town minor league baseball) |

Washington | Fayetteville Christian | Eagles |

Washington | Greenland | Pirates |

Washington | Haas Hall | Mastiffs |

Washington | Har-Ber | Wildcats |

Washington | Lincoln | Wolves |

Washington | Prairie Grove | Tigers |

Washington | Shiloh Christian | Saints |

Washington | Southwest Junior | Cougars |

Washington | Springdale | Red Bulldogs |

Washington | Springdale Police Dept. | Fuzz (football, 1987) |

Washington | Springdale Fire Dept. | Hose Jockeys (football, 1987) |

Washington | Tontitown | Grapers |

Washington | University High | Cardinals (basketball, 1929) |

Washington | West Fork | Tigers |

Washington | Winslow | Squirrels |

Washington | Winslow | Independents (basketball, 1929) |

Rachel Whitaker is the Shiloh Museum’s research specialist.