Down by the Old Mill Stream

Online Exhibit

Van Winkle Mill, Van Hollow (Benton County), early 1900s. Marilyn Larner Hicks Collection (S-90-10-39)

Imagine a time when there were no grocery stores. A time when people lived in the hills and hollows of the Ozark Mountains, growing crops and raising livestock in order to survive. Corn was important because it fed people and animals. It could be traded for other goods or turned into alcohol. Millers were important, too. In 1846 the State of Arkansas passed an act exempting millers from “serving on juries, working on roads, and in the performance of [normal] military duty.”

Today we think of gristmills as romantic old places, but once they were a major part of many rural communities. They provided families with an easy way to grind their grain (grist), brought folks together to trade news and gossip, and often functioned as a post office and mercantile store. According to Ozark folklorist Otto Ernest Rayburn, a trip to the mill was often a family occasion. Some folks traveled miles, hunting for meat and camping at the mill while waiting to have their grain milled. Dances might be held, marriages performed, doctors consulted. On Saturday afternoons at one mill in Madison County, fish trapped in the millrace after the gates were closed for the Sabbath were auctioned.

Folks could grind their grain at home, but it was a difficult, time-consuming process. One type of homemade mill involved tying a heavy maul to one end of a pole which was balanced on a forked limb pushed into the ground. When the free end of the pole was moved up and down, the maul fell into a hollowed-out tree stump full of dried corn. Having a community mill made a lot of sense.

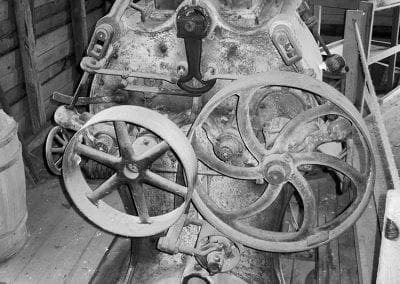

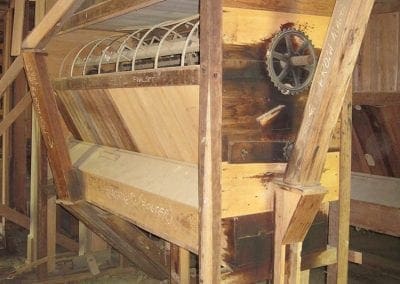

Roller mill machinery, probably salvaged after a fire, War Eagle Mill, 1920s-1930s. Mrs. Gene Layman Collection (S-90-36-2)

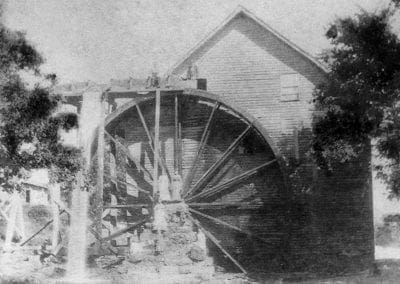

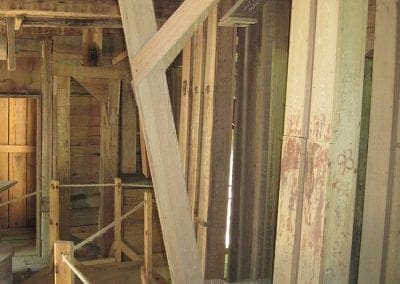

Early gristmills were simple affairs—a building, a source of water such as a stream or spring, and a water wheel to channel the energy of the flowing water and use it to turn one millstone upon the other. A few mills, like Engel’s Mill near Farmington, were powered by mules or oxen on a treadmill. Local hardwood was used for the building and the water wheel. The belts that ran on the pulleys were made of home-tanned leather. Many millstones were quarried locally, but the stone wasn’t as good as that imported from France.

The miller’s job wasn’t easy. He hauled heavy sacks of grain, worked round-the-clock during harvest time, and worried about fire and flood. Dams, millponds, and milling equipment needed constant maintenance and repair. In payment for his work, the miller took a portion of grain (the “toll”) from each milling job. We don’t know why, but area mills seemed to change hands often. Some families, such as the Basores of Carroll County, specialized in gristmills, building new mills and improving old ones before moving on to the next challenge.

The Civil War was hard on mills. Unlike other area commanding officers on both sides of the conflict, Confederate General Ben McCulloch believed that mills should be destroyed. He wrote, “Every man who is a patriot and sound southern man will be the first to put the torch to his own grain or mill rather than have them left to aid the enemy.” In 1862 McCulloch ordered the burning of Fayetteville’s steam mill which produced 10,000 pounds of flour daily. The owners pleaded for the removal of their equipment but were denied. Mills which escaped destruction were often captured, the grain bought or seized to feed the troops. During the occupation of the Rhea Community, miller William Rhea showed on which side his sympathies lay. He charged the Confederates 2½¢ a pound for flour while the Federals were charged double.

After the war old mills were rebuilt and new ones begun. Many were powered with steam engines which didn’t require the flowing water of a water mill. But they did need lots of wood to fire the boiler. At Rhea’s Mill, the men supplying the wood to fire the boilers were paid 25¢ a day and received free flour and meal and wholesale prices at the owner’s mercantile store. The mill workers had a similar deal, but received $2 a day.

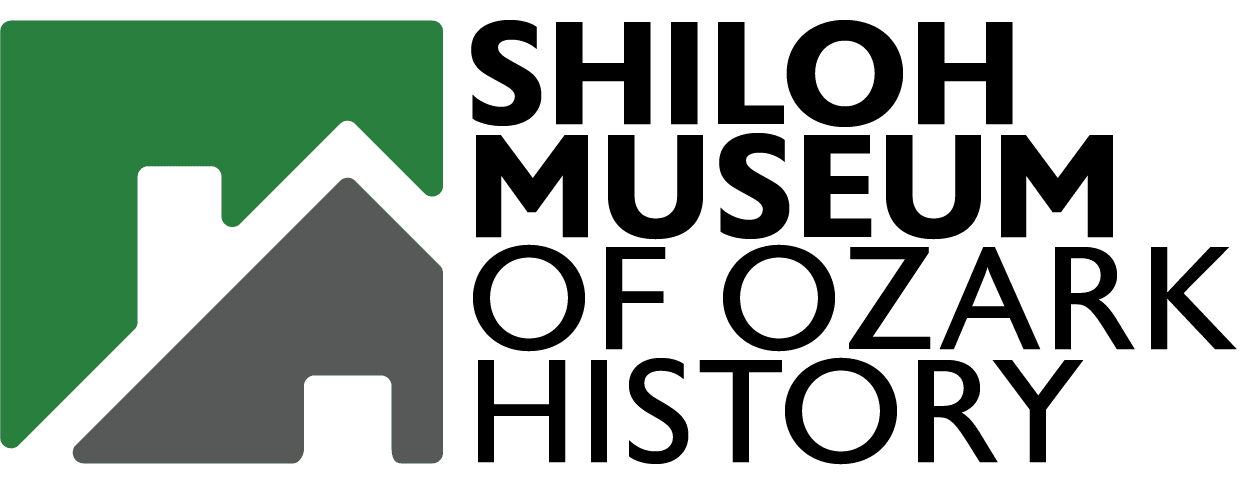

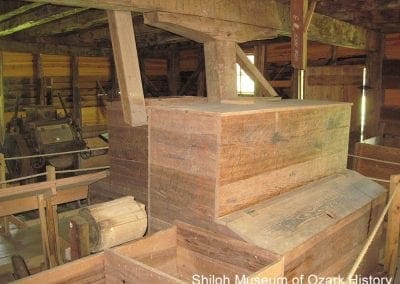

Milling began to change in the 1880s with the invention of the roller mill. Corrugated metal rollers and other advanced processing equipment ground flour finer and faster than the old millstones. With the coming of the railroads new markets opened up. Area farmers looking to make a profit used agricultural innovations to plant more acreage in soft winter wheat and corn. Some mills went into the flour business in a big way. In the early 1900s the Berryville Milling Company imported wheat from the North to mill and market.

Gristmills had their own brands of flour, often poetically named. At Johnson they offered “Cream of the Harvest” and “White Dove.” Over in West Fork “Jersey Lily” was a favorite while Kingston had “Pride of Arkansas.” At Osage Mills Dr. Philo Alden wrote of his “Gold Dust” brand flour, “A bride’s best dower, and when she’s through the making, her bread is light and sweet and white, and shows a perfect baking.” Some mills used their water and steam power to saw timber, card wool, and gin (process) cotton. A few mills even operated a government distillery. Having different business ventures made running a mill more profitable and kept customers coming back as the needs of the community changed.

The early 20th century saw a decline in gristmills. Railroads and the automobile made it easier to get ready-made flour to the stores, diets were more varied, and fewer folks were growing grain for home use or sale. New food-safety laws forced some mills to change to milling animal feed only. A few millers held on into the 1960s and 1970s, but one by one the mills went away—burned down, washed away, tumbled down, and forgotten. Today only the War Eagle Mill keeps on grinding.

Van Winkle Mill, Van Hollow (Benton County), early 1900s. Marilyn Larner Hicks Collection (S-90-10-39)

Imagine a time when there were no grocery stores. A time when people lived in the hills and hollows of the Ozark Mountains, growing crops and raising livestock in order to survive. Corn was important because it fed people and animals. It could be traded for other goods or turned into alcohol. Millers were important, too. In 1846 the State of Arkansas passed an act exempting millers from “serving on juries, working on roads, and in the performance of [normal] military duty.”

Today we think of gristmills as romantic old places, but once they were a major part of many rural communities. They provided families with an easy way to grind their grain (grist), brought folks together to trade news and gossip, and often functioned as a post office and mercantile store. According to Ozark folklorist Otto Ernest Rayburn, a trip to the mill was often a family occasion. Some folks traveled miles, hunting for meat and camping at the mill while waiting to have their grain milled. Dances might be held, marriages performed, doctors consulted. On Saturday afternoons at one mill in Madison County, fish trapped in the millrace after the gates were closed for the Sabbath were auctioned.

Folks could grind their grain at home, but it was a difficult, time-consuming process. One type of homemade mill involved tying a heavy maul to one end of a pole which was balanced on a forked limb pushed into the ground. When the free end of the pole was moved up and down, the maul fell into a hollowed-out tree stump full of dried corn. Having a community mill made a lot of sense.

Roller mill machinery, probably salvaged after a fire, War Eagle Mill, 1920s-1930s. Mrs. Gene Layman Collection (S-90-36-2)

Early gristmills were simple affairs—a building, a source of water such as a stream or spring, and a water wheel to channel the energy of the flowing water and use it to turn one millstone upon the other. A few mills, like Engel’s Mill near Farmington, were powered by mules or oxen on a treadmill. Local hardwood was used for the building and the water wheel. The belts that ran on the pulleys were made of home-tanned leather. Many millstones were quarried locally, but the stone wasn’t as good as that imported from France.

The miller’s job wasn’t easy. He hauled heavy sacks of grain, worked round-the-clock during harvest time, and worried about fire and flood. Dams, millponds, and milling equipment needed constant maintenance and repair. In payment for his work, the miller took a portion of grain (the “toll”) from each milling job. We don’t know why, but area mills seemed to change hands often. Some families, such as the Basores of Carroll County, specialized in gristmills, building new mills and improving old ones before moving on to the next challenge.

The Civil War was hard on mills. Unlike other area commanding officers on both sides of the conflict, Confederate General Ben McCulloch believed that mills should be destroyed. He wrote, “Every man who is a patriot and sound southern man will be the first to put the torch to his own grain or mill rather than have them left to aid the enemy.” In 1862 McCulloch ordered the burning of Fayetteville’s steam mill which produced 10,000 pounds of flour daily. The owners pleaded for the removal of their equipment but were denied. Mills which escaped destruction were often captured, the grain bought or seized to feed the troops. During the occupation of the Rhea Community, miller William Rhea showed on which side his sympathies lay. He charged the Confederates 2½¢ a pound for flour while the Federals were charged double.

After the war old mills were rebuilt and new ones begun. Many were powered with steam engines which didn’t require the flowing water of a water mill. But they did need lots of wood to fire the boiler. At Rhea’s Mill, the men supplying the wood to fire the boilers were paid 25¢ a day and received free flour and meal and wholesale prices at the owner’s mercantile store. The mill workers had a similar deal, but received $2 a day.

Milling began to change in the 1880s with the invention of the roller mill. Corrugated metal rollers and other advanced processing equipment ground flour finer and faster than the old millstones. With the coming of the railroads new markets opened up. Area farmers looking to make a profit used agricultural innovations to plant more acreage in soft winter wheat and corn. Some mills went into the flour business in a big way. In the early 1900s the Berryville Milling Company imported wheat from the North to mill and market.

Gristmills had their own brands of flour, often poetically named. At Johnson they offered “Cream of the Harvest” and “White Dove.” Over in West Fork “Jersey Lily” was a favorite while Kingston had “Pride of Arkansas.” At Osage Mills Dr. Philo Alden wrote of his “Gold Dust” brand flour, “A bride’s best dower, and when she’s through the making, her bread is light and sweet and white, and shows a perfect baking.” Some mills used their water and steam power to saw timber, card wool, and gin (process) cotton. A few mills even operated a government distillery. Having different business ventures made running a mill more profitable and kept customers coming back as the needs of the community changed.

The early 20th century saw a decline in gristmills. Railroads and the automobile made it easier to get ready-made flour to the stores, diets were more varied, and fewer folks were growing grain for home use or sale. New food-safety laws forced some mills to change to milling animal feed only. A few millers held on into the 1960s and 1970s, but one by one the mills went away—burned down, washed away, tumbled down, and forgotten. Today only the War Eagle Mill keeps on grinding.

The Miller’s Tale

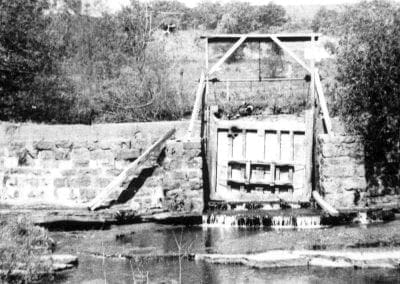

Many mills use water power to run their machinery. Water from a spring or stream is gathered into a millpond. The water is held back by a dam [1] with a sluice gate [2]. When the sluice gate is opened, water is released into a chute-like flume [3] or a pipe [4] and travels to the water wheel or turbine.

P-4818

1. War Eagle River dam, Hawkins Mill, Huntsville (Madison County), 1940s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4818)

P-1016

2. Sluice gate, Buchanan-Moore Mill, Cane Hill (Washington County), 1910s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1016)

P-4814

3. Flume, unidentified mill, probably Strain community (Washington County), circa 1900. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4814)

Water for an overshot wheel [5] falls down into the wheel’s buckets, causing it to turn. On a breastshot wheel [6], water comes in level with the wheel’s center. An undershot wheel [7] works directly in the stream where water is diverted into a small channel. An undershot wheel is easier to build than an overshot wheel, but it isn’t as effective. A turbine [8] works like a small water wheel, but it sits flat in the water. It can work even when the water is low.

85-277-54

5. Overshot wheel, Buchanan-Moore Mill, Cane Hill (Washington County), 1910s. Cohea, photographer. Martha Moore Collection (S-85-277-54)

99-26-2

6. Breastshot wheel, Stultz Mill, Springdale, 1900s. Speece and Aaron, photographers. Gale Hairston Collection (S-99-26-2)

Some mills are powered by steam engines [9]. Burning wood heats water in a boiler, making steam. Steam pressure forces pistons to move, which then move other machinery. Exhausted steam leaves through a tall flue pipe or chimney [10]. The power turns a driveshaft which then turns the gears, pulleys, and belts [11] attached to the mill’s machines, making them work.

83-324-42

9. Steam engine, Cincinnatti Flour Mill, Cincinnatti (Washington County), 1900s-1910s. Ruth Ann Wilson Collection (S-83-324-42)

rhea chimney

10. Chimney from Rhea’s Mill, now located at Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, 2010.

Grain is channeled into the center hole of a pair of grooved millstones [12 and 13]. The bedstone (on the bottom) stays still while the runnerstone spins on top. The thickness of the meal or flour depends on how close the stones are to one another.

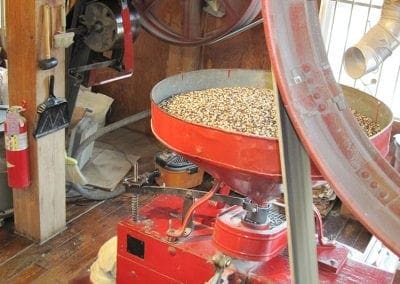

In a roller mill, grains of wheat are first sent to the scourer [14] to be cleaned before being crushed between the roller’s [15] corrugated metal bars.

86-94-5

12. Mr. Johnson and his millstones, Johnson Mill, Johnson (Washington County), 1960s-1970s. David Quin Collection (S-86-94-5B)

The crushed grain travels to the different machines by way of elevators [16], chutes which contain small cups attached to long belts. The grain may go through another roller before it goes to one or more bolters [17] which sift the flour into different-sized particles.

The final product is packaged into sacks [18]. Flour is finely ground; meal is more coarse. Chops (crushed corn) and shorts (leftovers from milling wheat) were fed to livestock.

93-83-6

16. Elevator cup, Johnson Mill, Johnson (Washington County), 1970. Charles Allonby, photographer. Mrs. Bobbie Kennard Collection (S-93-83-6)

Photo Gallery

P-1014

Allen’s Mill, Cave Springs (Benton County), 1910s. The mill stood near the present-day shore of Lake Keith. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1014)

P-1020

War Eagle Mill, later War Eagle Roller Mill, War Eagle (Benton County), 1910s. Sylvanus Blackburn built the first mill at War Eagle in the 1830s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1020)

war eagle mill

War Eagle Mill, War Eagle (Benton County), July 2010. Zoe Medlin Lancaster Caywood and her family built this mill in 1973. The Roenigks bought the mill in 2004. Today it’s the only working gristmill in Arkansas.

92-92-2

Hawkins Mill, Harrison (Boone County), 1900s-1910s. James Hawkins Sr. built this mill in the 1840s, just a few years after he built a mill in Madison County. Dewey Taylor Collection (S-92-92-2)

85-45-18

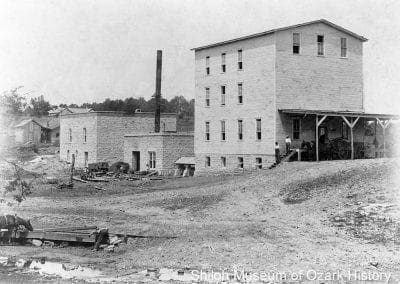

Berryville Milling Company (later North Arkansas Milling Company), Berryville (Carroll County), 1900s-1910s. In 1910 the mill could grind up to 100 barrels of grain daily and store 40,000 bushels of wheat and 500,000 pounds of flour. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-45-18)

85-18-28

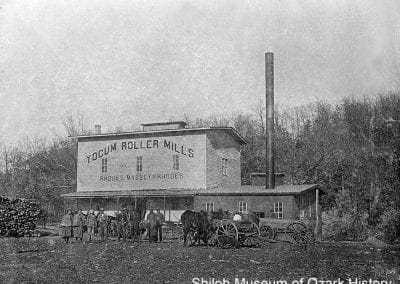

Yocum Roller Mills, Yocum (Carroll County), 1900s-1910s. Rhodes and Massey built this steam-powered roller mill in 1894. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-18-28)

92-109-15

Kingston Roller Mill (“Old Red Mill”), Kingston (Madison County), circa 1905. In 1898, the Basore brothers built this steam mill with partners John Grigg and Joel Bunch. The mill ceased operations in the late 1920s and was likely torn down in the 1950s. John D. Little Collection (S-92-109-15)

85-34-3

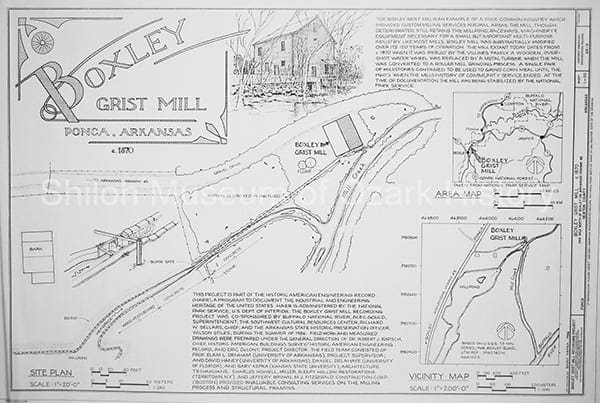

Villines Mill, Boxley (Newton County), 1960s-1970s. National Register of Historic Places, 1974. In 1870 Robert Villines began grinding corn at this mill. Clyde Villines ground the last sack of grain here in the 1950s. Today the mill is part of the Boxley Valley Historic District of the Buffalo National River. A.T. Johnson, photographer. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-34-3)

85-45-1

Marble Falls Mill, Marble City (formerly Wilcockson) (Newton County), 1909-1910. Peter Beller first put a mill at this site in about 1840. Over the years new owners rebuilt and remodeled the mill. Some time in the early 20th century it was torn down. James T. Braswell, photographer. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-45-1)

P-1008

Moore’s Mill (later Barton’s/Eureka Roller Mill), Cincinnati (Washington County), 1900s-1910s. A three-story, steam-powered roller mill went up in Rag Hollow, southeast of Cincinnati, sometime around 1883. Dave, “Han” (Hannibal), and “Gum” (Montgomery) Moore were the first owners, followed by George Barton in the 1890s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1008)

85-277-51

Buchanan-Moore Mill (previously Pyeatte-Moore Mill), Cane Hill (Washington County), circa 1910. National Register of Historic Places, 1982. The history of this mill begins with John Pyeatte, who built a water mill north of Cane Hill around the time of the Civil War. In 1907, that mill was moved to the location pictured here, on the banks of Jordan Creek south of Cane Hill. Martha Moore Collection (S-85-277-51)

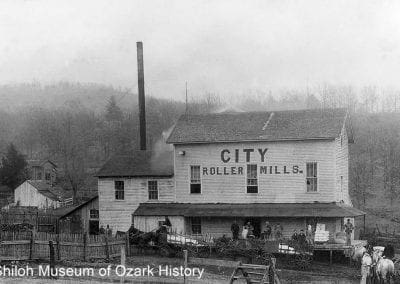

P-341

City Roller Mills (“Old White Mill”), Fayetteville (Washington County), 1900s-1910s. Supposedly the first steam mill in Northwest Arkansas was built on this site southeast of the downtown square in 1854. A mill operated here into the 1920s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-341)

P-455A

Farmer’s Alliance and Industrial Union Milling Company (previously Engels Mill, later Ozark Milling Company), Farmington (Washington County), 1900s-1910s. W. H. Engels built this mill after the Civil War. It was used for a time as a licensed distillery. Milling ceased there in the late 1920s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-455)

85-325-2038

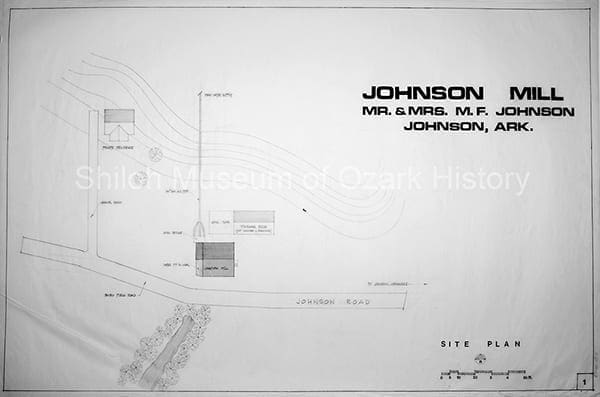

Johnson Mill, Johnson (Washington County), possibly 1890s. National Register of Historic Places, 1976. A mill stood on this site as early as 1835 before it was burned down during the Civil War. Jacob Q. Johnson rebuilt the mill in 1867. The Johnson family sold flour, meal, and feed (including earthworm feed for bait growers) until 1978 when miller Frank Johnson retired. Ray Watson Collection (S-85-325-2038)

inn at the mill

Johnson Mill exterior, Johnson (Washington County), July 2010. Today the Johnson Mill is part of the Inn at the Mill hotel.

P-4814-1

Unidentified mill, probably Strain community (Washington County), circa 1900. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4814)

P-1005

Rhea’s Mill (later Valley Steam Mill), Rhea (Washington County), 1900s. Built north of Prairie Grove in 1854, William Rhea bought the mill in 1859. It was destroyed during the Civil War. Rhea rebuilt the mill, and it remained in operation until 1917. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1005)

rheas mill

Rhea’s Mill reconstructed chimney, Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park (Washington County), July 2010. In 1956 the owners of Rhea’s Mill donated the mill’s 55-foot sandstone chimney to Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, where it serves as a monument to the battle’s fallen soldiers.

rhea millstone

Rhea’s Mill millstone, Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park (Washington County), July 2010.

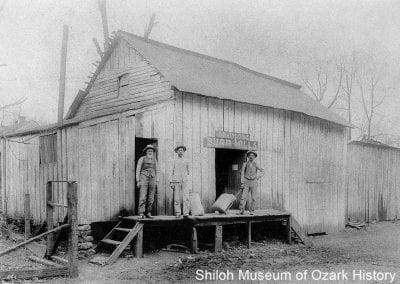

2006-177-12

Springdale Burr Mills (also known as Little Red Mill and Bowman Mill, later Byars Grist Mill), Springdale (Washington County), 1913. Located along Spring Creek, this steam mill once stood on the northeast corner of what is now the Shiloh Museum’s property. The mill was built in the late 1870s or 1880s and had many owners over the years. John and Louise Havens Collection (S-2006-177-12)

2006-177-11

Interior of Springdale Burr Mills (also known as Little Red Mill and Bowman Mill, later Byars Grist Mill), Springdale (Washington County), 1913. In 1912-1913, James Havens and his brother-in-law, James Bowmen, were part owners of the mill. Family legend has it that the main part of their business was selling grain to the folks in Tontitown to make alcohol. John and Louise Havens Collection (S-2006-177-11)

99-26-2

Stultz Mill, Springdale (Washington County), about 1908. Located north of Springdale, this mill is said to have been built about 1901. Today the mill site is part of the Springdale Wastewater Treatment Plant property. Speece and Aaron, photographers. Gale Hairston Collection (S-99-26-2)

84-2-156

White River Mills, West Fork (Washington County), 1900s-1910s. This steam mill was built not long after 1890. The mill marketed such brands as “Jersey Lily” and “Rose Economy” flour. Sometime in the late 1910s or early 1920s the mill burned down. Robert G. Winn Collection (S-84-2-156)

JDW02-16

Hawkins Mill near Huntsville (Madison County), 1940s. William Hawkins, Sr. built this gristmill in 1838 on the banks of the War Eagle River east of Huntsville. The Hawkins family was still grinding grain here in 1928. J. D. and Marie Watkins/Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society Collection (JDW02-16)

Villines Mill Photo Gallery

Located in Boxley (Newton County), the Villines Mill was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. View architectural drawings of the mill (2.8 MB pdf document).

boxley 12

Front entrance, with the doorway at wagon height. The porch floor was reproduced based on the 1986 Historic American Engineering Record drawings.

boxley millpond

Millpond. When water was needed to run the mill, it was channeled into a stream and released through a sluice gate into a chute-like flume. As the water fell onto the waterwheel or turbine, it caused the main driveshaft to turn.

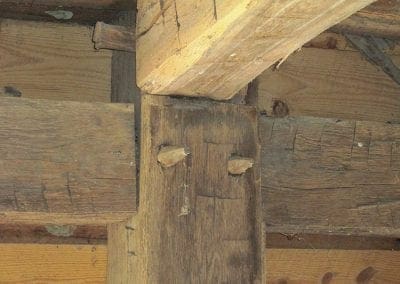

boxley 50

Pulleys connected to the main driveshaft of the turbine, first floor. As the driveshaft spun around, it turned the belts, pulleys, and gears connected to the mill’s various machines and equipment.

boxley 43

Looking down at the turbine’s bevel gears. When the water wheel was replaced in 1901 with a more powerful turbine, the entire first floor was raised to accommodate the height needed for the water to effectively drop onto the turbine.

boxley 5

Office addition and flume at the back of the mill. The rotting wood flume was replaced with concrete around 1901.

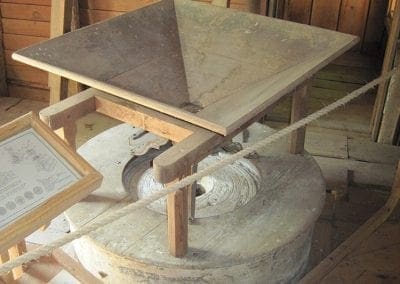

boxley 36

Millstone assembly, first floor. These millstones were used exclusively to grind corn once roller mill equipment was added to process wheat. As grain was put into the wooden hopper (on top), it fell through the eye of the runner stone and onto the flat surface of the bed stone, where it was ground. The top part of the runner stone is made of plaster.

boxley 39

Winch over the millstone assembly, first floor. The winch was used to raise and tilt the runner stone, so that both stones could be dressed (refinished) as necessary.

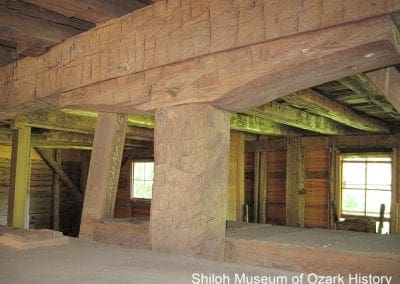

boxley 19

Hurst frame used to support the heavy millstones, beneath the first floor. The plaster bottom of the bed stone can be seen.

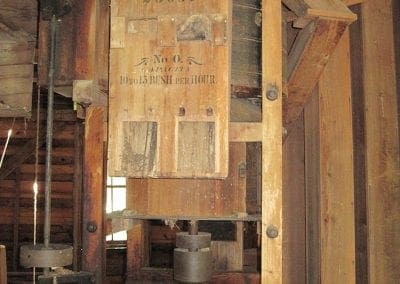

boxley 55

Vertical wheat scourer, second floor. The scourers were part of the roller mill assembly and were used to clean the grain before processing. This one advertised that it could clean “10-15 bushels per hour.”

boxley 32

Open elevator chute with a canvas belt fitted with metal cups, first floor. The elevator transported grain and flour from one machine to another throughout the building’s three floors.

boxley 25

Reduction roller mill, first floor. After the grain was cleaned it was crushed in a break roller before being further crushed between the corrugated metal rollers of the reduction roller.

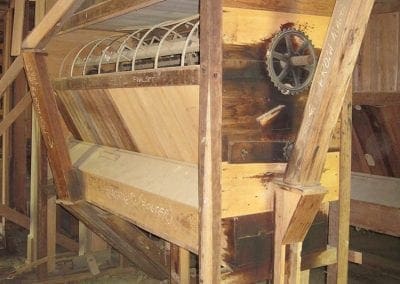

boxley 62

Hexagonal reel bolter, second floor. Flour was brought by elevator into the center of the cloth-covered bolter. As the bolter spun, fine grains of flour were sifted through the cloth into the bin below which was fitted with an augur designed to move the flour to another elevator.

Johnson Mill and Villines Mill Architectural Drawings

Johnson Mill (Washington County) was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. University of Arkansas architecture students created scale drawings of the mill in 1985. View the scale drawings (3.3 MB pdf document).

Villines Mill, aka Boxley Mill (Newton County) was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Drawn on behalf of the Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service, in 1986. View the scale drawings (2.8 MB pdf document).

Credits

“Account Books of the Cane Hill Mill.” Flashback, Vol. 15, No. 5 (November 1965).

Allen, Eric. “Remembering the Old Boxley Mill.” Arkansas Gazette, December 5, 1971.

Banton, Margaret. “Farmington City Hall Honors Ms. Shepherd with Reception.” Farmington Enterprise, February 19, 1987.

Banton, Margaret. “History of Farmington” series. Prairie Grove Enterprise, June 6, 1986; June 19, 1986; June 26, 1986; July 3, 1986.

Basore, George W. “The Flour Mills of Berryville and Carroll County in the Early Days.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXXV, No. 3 (September 2000).

Basore, George W. “Memoirs of an Early Northwest Arkansas Millwright” series. Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVII, No. 4 (Winter 1972) and Vol. XVIII, No. 1/Vol. XVIII, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 1973).

Belknap, Lucile McWilliams. “Old Mill Was Center of Rootville Community Life.” Undated article, Shiloh Museum research files.

Blackburn to Lee deed, April 20,1857. Washington County Archives Land Records, 1834-1991.

“Boxley Mill Gets Roof, Other Repair.” Newton County Times, Septebmer 28, 1989.

Braswell, O. Klute. “The True and Legendary Story of Yocum…Carroll County, Arkansas.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XIV, No. 4; Vol. XV, No. 1 (December 1969; March 1970).

Cain, William B. “Water Powered Hawkins Mill in Service for 100 Years,” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXVI, No. 4 (Winter 1981-1982).

Campbell, William S. One Hundred Years of Fayetteville: 1828-1928. 1928. Reprint, Fayetteville: Washington County Historical Society, 1977.

“Cave Springs.” Northwest Arkansas Times, June 14, 1960.

Cave Springs Memories. Cave Springs Library Board, circa 1995.

“County’s Oldest Landmark Succumbs in Flood.” Madison County Record, June 15, 1944.

Croley, Victor A. “Marble Falls Has Had Many Names.” Arkansas Gazette, 1968.

Dillard, Tom W. “Gristmill Once as Numerous as Kernels on an Ear of Corn,” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 4, 2007.

“Dogpatch Grist Mill Dedicated to Worker.” Marshall Mountain Wave, August 24, 1989.

“Early Mill Operated Near Farmington; Land Where Town Stands Platted in ’70.” Northwest Arkansas Times, June 14, 1960.

Fisher, Sarah. “Inn at the Mill Celebrates 10-year Anniversary,” Northwest Arkansas Times, October 12, 2001.

“From the North Arkansas Fair Catalogue and Premium List, 1910.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 3 (September 1961).

Funk, Erwin. “War Eagle Flour Mill Destroyed by Fire 1924.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 7, No. 5 (July 1962).

Gearhart, George. “Reminiscences of Old Anderson Township and its People.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 3, No. 3 (April 1953).

“Great Water Damage to Farms and Crops.” Madison County Record, June 15, 1944.

“Gristmill.” Old Sturbridge Village. http://www.osv.org/explore_learn/waterpower/grist.html. (page no longer available, 2019)

Hazen, Theodore R. “Flour Milling in America: A General Overview.”

Hazen, Theodore. “The Index Page of Mill Restoration.”

“Historic Waterwheel is Rejuvenated.” Eureka Springs Flashlight, September 1983.

History of Benton, Washington, Carroll, Madison, Crawford, Franklin, and Sebastian Counties, Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

“Hosea M. Benbrook, Oldest Male Citizen Knew Clay Helbert,” Northwest Arkansas Times, September 8, 1941.

Hudson, James F. “Settlement Geography of Madison County, Arkansas.” Master’s thesis, University of Arkansas, 1976.

Hudspeth, Cora Smith, and Alice Smith Doss. “Hawkins Mill at Dry Fork.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 3 (Autumn 1985).

Hughes, Michael A. “Wartime Gristmill Destruction in Northwest Arkansas and Military-Farm Communities.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 (Summer 1987).

Jines, Billie Allen. “From Cannon to Cave Springs – In Two Different Ways.” Cave Springs Scene, November 19, 1970.

Johnson, Mary Ellen. The Johnson Family: The Johnson Mill, A Tradition. Self-published, circa 1992.

Johnston, Dorothy M. History of the Rhea Community, Washington County, Arkansas. Self-published, 1987.

Johnston, Harold L. “Rhea.” Lincoln Leader, April 10, 1969.

Keesee, Irene. “The Jolly, Johnson Miller.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 23, No. 1, February 1975.

Lackey Walter F. History of Newton County, Arkansas. Point Lookout, Missouri: School of the Ozarks Press, 1950.

Lancaster, Zoe L. “War Eagle Mill.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Summer 1975).

Leung, Felicity. Grist and Flour Mills in Ontario, National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, Environment Canada. 1981.

Lemke, Walter J. “The Old Mill at Cane Hill.” Flashback, Vol. XI, No. 4 (November 1961).

Lof, Eric and Larry. Boxley Grist Mill. Self-published pamphlet, circa 2005.

Logan, Coy. “Mills.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXXV, No. 1 (March 2000).

Lynch, Bobbie Byars. “Early Mills of Washington County.” Flashback, Vol. 25, No. 1 (February 1975) and Vol. 25, No. 2 (May 1975).

Lynch, Bobbie Byars, ed. Shiloh-Springdale, 1878-1978. Springdale: Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, 1978.

“Marble City and Newton County, Arkansas, 1891.” Unidentified/undated newspaper clipping, Shiloh Museum research files.

McConnell, F. M. “History of the Middle Fork.” Flashback, Vol. XV, No. 2 (April 1965.)

McMurry, Neva Barnes. “Stark’s Nursery Shed.” Washington County Observer, July 29, 1982.

“Milling is Part of Cane Hill’s Past.” Unidentified newspaper, July 25, 1974. Shiloh Museum research files.

Neal, Lisa. “Johnson’s Water Mill.” Springdale News, December 16, 1985.

Nixon, Jennifer. “Mill Gives Guests History and Luxury.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, circa 2005.

“North Arkansas Milling Company.” Eureka Springs Times-Echo, July 6, 1990.

Norris, R. E. IV. “Yocum and the O’Neal Family.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXXII, No. 3 (Autumn 1986).

“Old Marble Falls Mill and Settlement Belong to the Past.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 4, No. 3 (November 1955).

“‘Old Mill’ Named to National Register of Historical Places.” Boone County Headlight, October 10, 1974.

Oliver, M. E. “Eventful History of Arkansas’ Old Hawkins Water Mill.” Ozarks Mountaineer, April 1959.

Payne, Ruth Holt. “Memorabilia of Early Mills.” Flashback, Vol. 13, #1 (February 1963).

Piercy, Maud, and Emmaline Rife. “Early Mills in Benton County.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Fall 1982).

Poorman, Forrest. “The Tandy K. Kidd Home and Mill.” Flashback, Vol. 40, No. 4 (November 1990).

Rayburn, Otto Ernest. “Going to Mill.” Ozark Country. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1941.

“Reactivates to Preserve Cane Hill Waterwheel.” Prairie Grove Enterprise, March 22, 1990.

Read, Julia S. “Farmington First Called Engel’s Mill.” Fayetteville Daily Democrat, June 11, 1936.

Robinson, Deborah. “September 8 Event to Highlight Mill Restoration.” Northwest Arkansas Times, August 30, 1990.

Russell, Conrad. “History of the Cane Hill Mill.” Flashback, Vol. 26, No. 2 (May 1976).

“Scenes of Our Heritage: Scroggins Mill.” Cave Springs Scene, July 22, 1971.

Scogin, Linda. “Canehill Mill Full of History.” Northwest Arkansas Times, April 17, 1990.

Shiras, Tom. “Century Old Mill Grinding on Every Day.” Southwest Times Record, August 15, 1937.

Sines, Helen N. “Savoy, Yesterday and Today.” Flashback, Vol. V, No. 2 (April 1955).

Stamps, Carl. “Grist Mills and Water Mills on Osage Creek.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXVIII, No. 3 (Autumn 1983).

Steele, Phillip. “History of the Johnson Mill.” Ozark View, Vol. 1, No. 1 (May 1993).

Steele, Phillip. “Johnson’s Mill.” Flashback, Vol. 26, No. 2 (May 1976)

Sutton, Leslie. “Echoes of a Lost and Quieter Time.” Northwest Arkansas Times, January 5, 1977

“This Was Carroll County.” Harrison Daily Times, February 21, 1992.

Vaughan, Ardella. “History of Marble Falls.” Boone County Headlight, April 11, 1968.

Waits, Wally. “The Hawkins Mill.” Madison County Musings, Vol. III, No. 1 (Spring 1984).

“War Eagle Water Mills Go Back to 1838.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 4, No. 6 (September 1959).

“W. H. Rhea, Rhea’s Mill Merchant, Totals His Losses Before and After the Battle of Prairie Grove.” Flashback, Vol. 6, No. 4 (July 1956).

“White River Mills of West Fork.” Washington County Observer, September 1, 1983.

Whittemore, Carol, ed. Fading Memories II: Stories of Madison County People and Places. N. p. 1992.

Wilson, Charles Morrow. “Mills of the Gods.” Farm and Ranch, December 22, 1928.

Wilson, Jaunita. The History of Cincinnati, Arkansas, 1836-1986. Siloam Springs, AR: Siloam Springs Printing, 1986.

Winn, Robert G. “West Fork Grist Mill of 1900.” Undated/unidentified newspaper clipping, Shiloh Museum research files.