Make Do

Make Do

Online ExhibitWaste Not, Want Not

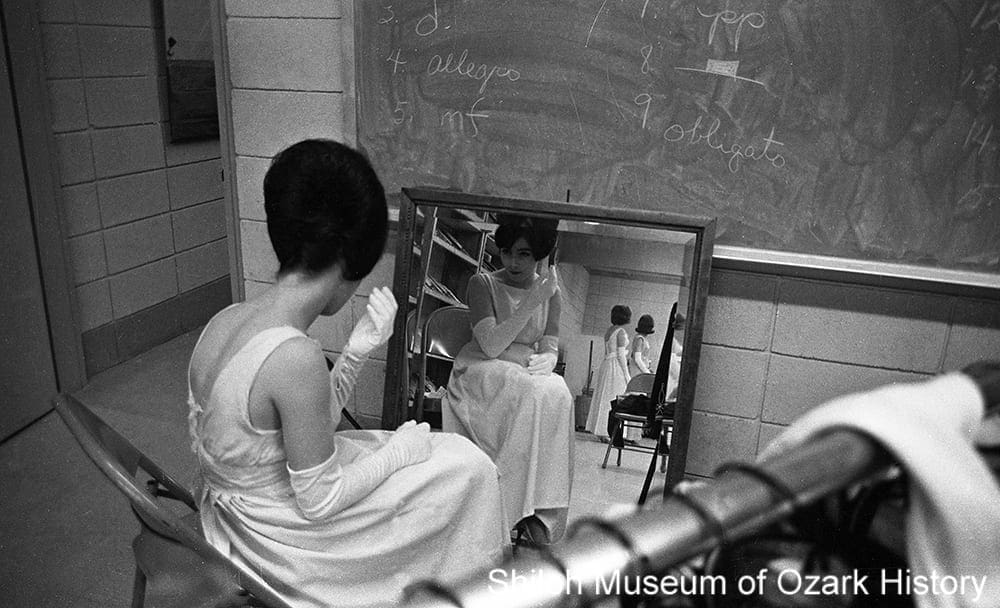

Participants in the feed-sack dress contest at Huntsville Vocational High School (Madison County), 1930s. May Reed Markley Collection (S-84-155-499)

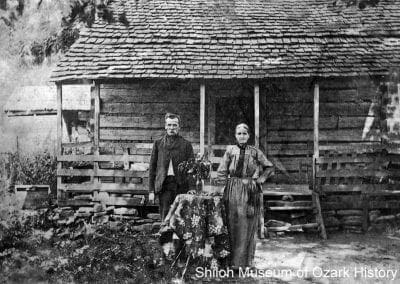

During the 19th century, settlers came to the Arkansas Ozarks to farm and homestead. Because cash was scarce and stores were few and far between, they built homes out of logs, wove cloth from yarn made of sheep wool, and fashioned tools and household goods from wood, iron, leather, and other raw materials. When something broke or wore out, it was often repaired rather than thrown away. If a new tool or household item was needed, it might be made from discarded objects, such as a quilt made from scraps of worn-out clothing.

Throw-Away Society

This self-reliance continued into the first half of the 20th century, especially during the economic hardship caused by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Times began to change with the nation’s growing prosperity following World War II. Incomes rose and the number of manufacturers increased. New, affordable products filled store shelves. Some were designed to be thrown away after one use, like paper plates and aluminum foil. Folks got into the habit of discarding unwanted or damaged items.

Changing Times, Time to Change

In 2020, two worldwide events speak to the need of making do and upcycling—the 50th anniversary of Earth Day and the COVID-19 pandemic. The first serves as a reminder to reduce our waste, with one pathway being the creative repurposing of objects. The second is a sad reality for millions of unemployed Americans who will likely need to make do with what they have for now, through mending and improvising.

About This Exhibit

In the spirit of make-do and upcycling, the display furniture in this exhibit has been made from cardboard boxes and other found materials. They will be repurposed or recycled once the exhibit ends.

Did You Know?

• The average American goes through 77 pounds of cardboard each year

• Amazon ships an average of 608 million packages each year

• Nearly 100 billion cardboard boxes are produced annually in the U.S.; of them, 75% are recycled

• Recycling cardboard takes only 76% of the energy needed to make new cardboard

Do Your Part

Take a good look at the things in your life and what you truly need. What steps can you take to make do and upcycle?

Waste Not, Want Not

Participants in the feed-sack dress contest at Huntsville Vocational High School (Madison County), 1930s. May Reed Markley Collection (S-84-155-499)

During the 19th century, settlers came to the Arkansas Ozarks to farm and homestead. Because cash was scarce and stores were few and far between, they built homes out of logs, wove cloth from yarn made of sheep wool, and fashioned tools and household goods from wood, iron, leather, and other raw materials. When something broke or wore out, it was often repaired rather than thrown away. If a new tool or household item was needed, it might be made from discarded objects, such as a quilt made from scraps of worn-out clothing.

Throw-Away Society

This self-reliance continued into the first half of the 20th century, especially during the economic hardship caused by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Times began to change with the nation’s growing prosperity following World War II. Incomes rose and the number of manufacturers increased. New, affordable products filled store shelves. Some were designed to be thrown away after one use, like paper plates and aluminum foil. Folks got into the habit of discarding unwanted or damaged items.

Changing Times, Time to Change

In 2020, two worldwide events speak to the need of making do and upcycling—the 50th anniversary of Earth Day and the COVID-19 pandemic. The first serves as a reminder to reduce our waste, with one pathway being the creative repurposing of objects. The second is a sad reality for millions of unemployed Americans who will likely need to make do with what they have for now, through mending and improvising.

About This Exhibit

In the spirit of make-do and upcycling, the display furniture in this exhibit has been made from cardboard boxes and other found materials. They will be repurposed or recycled once the exhibit ends.

Did You Know?

• The average American goes through 77 pounds of cardboard each year

• Amazon ships an average of 608 million packages each year

• Nearly 100 billion cardboard boxes are produced annually in the U.S.; of them, 75% are recycled

• Recycling cardboard takes only 76% of the energy needed to make new cardboard

Do Your Part

Take a good look at the things in your life and what you truly need. What steps can you take to make do and upcycle?

Artifact Gallery

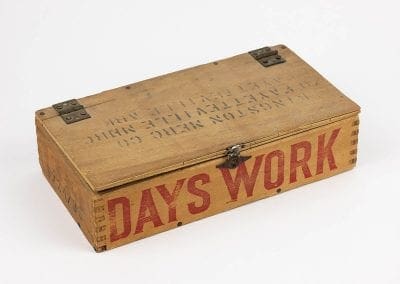

2012-98

Storage Box. Made from a chewing-tobacco crate by S. L. “Semp” Phillips of Ribbon Ridge (Madison County), 1930s-1980s. He used it to store important papers. Joyce Sue Simkins Collection (S-2012-98)

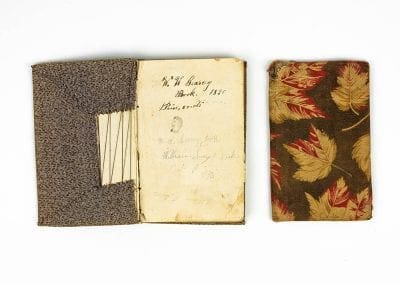

97-60-20-68-19-1027

School Books. Covered with fabric to help stabilize, protect, and/or freshen the look of the books’ covers. Left: Webster’s Elementary Spelling, late 19th century. From the Bever family near Hindsville. Right: Smith’s New Grammar, 1869. Used by Wesley H. Searcy in the Friendship Community, east of Springdale. Left: Ada Lee Smith Shook Collection (S-97-60-20). Right: Lockwood L. Searcy Collection (S-68-19-1027)

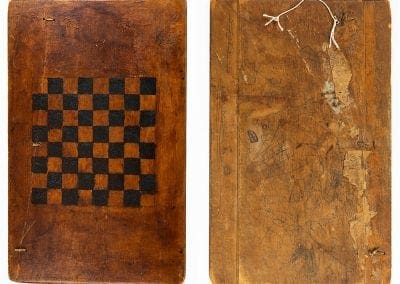

2004-93-combined1

Apron. Made from a Red Comb Poultry Feeds feed sack (a cloth bag used to hold dry food for chickens) and mended at a later date, probably by Gertrude Pond of Fayetteville, mid-20th century. Pat Pond Collection (S-2004-93-69)

2019-33-3-1combo

Checkerboard. Possibly made from a cabinet-door panel, with rawhide strips used to mend a break in the wood, possibly 20th century. Used by the Vaughan family of Hindsville. Patricia Laird Vaughan Collection (S-2019-33-3)

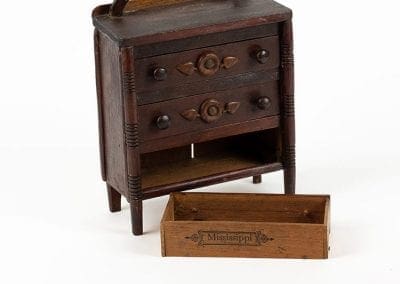

71-19-4

Toy Chest of Drawers. Drawers made from cigar boxes by Martha Ann Cline Smyer of Hindsville, 1886. She made the chest, a toy clock, and a four-poster bed for her children to play with and to serve as a memento from their mother, “to keep when I cease to work.” A skilled craftswoman, she also made artificial flowers from fish scales which she ordered from Florida. Smyer Family Collection (S-71-19-4)

2003-98-5

Dress. Made from feed sacks by Roxie Burch Robinson of Benton County, 1950s, for her granddaughter, Sandra K. Martin. Sandra K. Martin Collection (S-2003-98-5)

2003-98-2

Dress. Made from feed sacks by Roxie Burch Robinson of Benton County, 1950s, for her granddaughter, Sandra K. Martin. Sandra K. Martin Collection (S-2003-98-5)

84-203

Crutch. Made from a tree branch, possibly early 20th century. Found near a log cabin in Newton County about 1950. Scott Price Collection (S-84-203)

2015-4

Quilt (back). Made of leftover scraps of handwoven wool and cotton fabric, possibly in Northwest Arkansas, about 1900. (S-2015-4)

2007-108-2

Doll Chairs. Made from metal food cans by Merl Creger, 1930s–1940s, and given to Opal Schroeder of Springdale. Joe Roberts Collection (S-2007-108-2)

2011-90-3

Dish Towel. Made from a Springdale Hatchery feed sack by Silvia Exer Morrow of Washington County, 1920s-1930s. Carmyn Pitts Collection (S-2011-90-3)

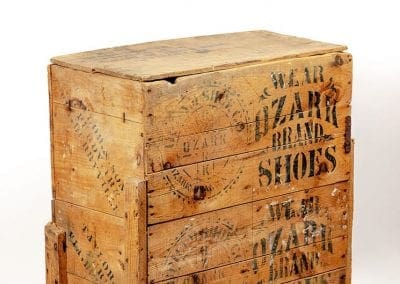

86-185

Flour Bin. Made from Ozark Brand Shoes crates, about 1915. The crates were originally sent to Taylor and Son’s general store in Purdy (Madison County). Shiloh Museum Purchase (S-86-185)

85-95-4

Slingshot. Made from a tree branch, possibly mid-20th century. Found under a home in Fayetteville. Carolyn Reno Collection (S-85-95-4)

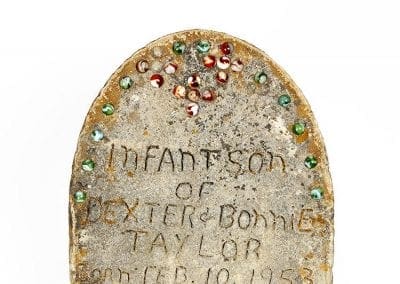

2005-27

Gravestone. Made from concrete by Bonnie Taylor of Felkins Creek (Madison County), 1953, for her baby son. The homemade marker was later replaced with a professionally made stone. Bonnie Taylor Collection (S-2005-27)

2001-80-2

Froe. Made from a tree branch and a farrier’s rasp (tool used to trim horses’ hooves), Washington County, 19th to early 20th century. A froe is a type of ax used for splitting wood along the grain. Maurice Colpitts Collection (S-2001-80-2)

91-99-66

Rug. Handwoven using strips of scrap cotton fabric by Mrs. R. B. Jones of Salem Mountain, near Sulphur City (Washington County), 19th century. From the A. W. and Elizabeth McGarrah Reed family, near Elkins. Ruth Morris Collection (S-91-99-66)

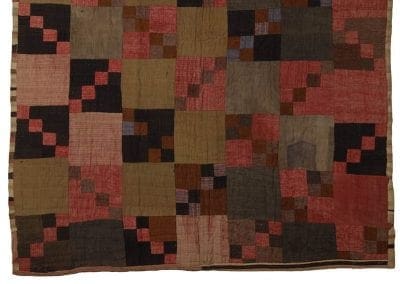

87-147-3

Quilt (back). Made of leftover scraps of handwoven wool fabric by Emma Bolinger of Kings River Township (Madison County), late 19th to early 20th century. At least one square was made from a garment, as indicated by the shadow of a removed pocket (visible in the lower right section of the quilt). Shiloh Museum Purchase (S-87-147-3)

90-60-1221

Rabbit Trap. Made from a log by Omer Winn of Winslow, early-mid 20th century. Robert Winn and Lyda Winn Pace Collection (S-90-60-1221)

2000-87

Water Pipe (Bong). Made from a Scope mouthwash bottle by a John Brown University student, 1968, and confiscated by a Siloam Springs Police Department officer. Captain Lee Owen Collection (S-2000-87)

93-129

Skirt. Made from a pair of red denim jeans by Jo Land Brady of Fayetteville and ornamented with fabric, embroidery, and bells, about 1973. Jo Land Brady Collection (S-93-129)

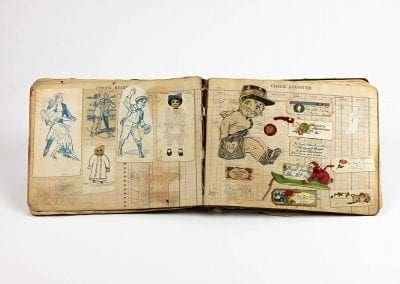

89-101-2

Scrapbook. Made from a check register, possibly by Myrl Charlesworth of Fayetteville, 1920s. The 1916-1918 register may have been used by the William Charlesworth Hardwood Lumber Company of Fayetteville. Later on Myrl and her sister, Yevonne, made and sold crafts at their store, Colona Dollhouse of West Fork, including apple-headed dolls and matchboxes decorated with postage stamps. Russell Charlesworth Collection (S-89-101-2)

2020-20

Rattle/Darning Egg. Made from a gourd (still full of seeds) and used as a rattle by Thomas J. Neill of Texas, who was born in 1860. After the Neill family moved to the Goshen area (Washington County) it was used by his sister Lottie to darn (repair) socks. Ricky Lewis Collection (S-2020-2)

87-229

Tablecloth. Crocheted with the cotton string used to close feed sacks, Springdale, late 1940s. Made by Alma Barnes who raised chickens commercially with her husband. Alma Barnes Collection (S-87-229)

The Upcyclers

Today many people are concerned about how our consumer economy and wastefulness impacts the environment. Creative folks have taken “make do” one step further through “upcycling,” a form of recycling. They take discarded objects or materials and transform them into new items, thus creating something of value while reducing waste in area garbage landfills.

Meet Some Local Upcyclers

Bea Apple and Trisha Logan

Jeans. Mended with a centuries-old decorative Japanese stitching method known as sashiko (“little stabs”), 2020, by Bea Apple, Trisha Logan, and Sadie McDonald of Hillfolk, a natural fiber and textile store in Bentonville. The process took about thirty hours and uses a running stitch (a line of small, even, in-and-out stitches) to create patterns. Courtesy Hillfolk

Bea Apple and Trisha Logan, Bentonville

Bea and Trisha are co-owners of Hillfolk, a store in the 8th Street Market which specializes in natural fibers and textiles and offers classes in contemporary and traditional fiber arts. They first became interested in sashiko, a decorative stitching technique, while researching Japanese textiles dyed with indigo (a plant). The pair are mostly self-taught, learning from books and through workshops. They find the art of sashiko meditative and love to “breathe new life into [their] favorite clothes by not hiding the holes and tears, but by drawing attention to the worn areas with beautiful, decorative stitching.”

Aubrey Costello

Dress. Remade from two dresses (one from the 1950s, the other from the 1980s) by Aubrey Costello of the Wesley area, 2020. Decorative additions include overdyed cloth, an embossed (stamped) design, old buttons, and a sleeve based on a 1968 clothing pattern. The dress was to be included in a show during the Spring 2020 Northwest Arkansas Fashion Week, which was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Courtesy Aubrey Costello

Aubrey Costello, Wesley

Aubrey has been sewing since age seven and now enjoys the role of storyteller with their work in costuming and fashion design. A vintage clothing enthusiast who objects to today’s disposable fashions, they hope to combat the wastefulness of the apparel industry by transforming lovely but damaged old clothes into “something that can be worn and appreciated, while preserving and honoring their original construction and aesthetic” (style). They use a variety of fine-sewing techniques to create original garments for all genders, sizes, and body types.

Darla Gray-Winter

Electric Guitar. Made from a cigar box by Darla Gray-Winter of Holiday Island, 2020. The bottle caps (lower right corner) control volume. Courtesy Darla Gray-Winter

Darla Gray-Winter, Holiday Island

Darla is an artist and luthier (maker of stringed instruments) who began customizing guitars for fun. After receiving professional training in the craft she took up making cigar-box guitars as a way to practice her fretwork technique. Frets are the raised elements on a guitar’s neck. She enjoyed making cigar-box guitars so much that they are now her specialty.

Dustin and April Griffith

Residence. Dustin and April Griffith’s shipping-container home, Eureka Springs (Carroll County), 2020. April Griffith, photographer.

Dustin and April Griffith, Eureka Springs

Dustin and April, whose degrees are in design, have long been attracted to the industrial look. They built their home out of six shipping containers and furnished it with repurposed objects as a way of making something new from cast-off items which have a history of their own. The containers’ many trips across the ocean are seen on their walls through handwritten notes in multiple languages. With little published about the specifics of building such homes, the couple learned along the way. Skilled family and friends helped, some trading services (such as plumbing) for what the pair could offer (motorcycle repair). One of the fun features about the house is that containers can be added when needed, just like building with Lego® blocks.

Learn more about the Griffith home in the “Large-Scale Upcyclers, Then and Now” section below.

Liz Lester

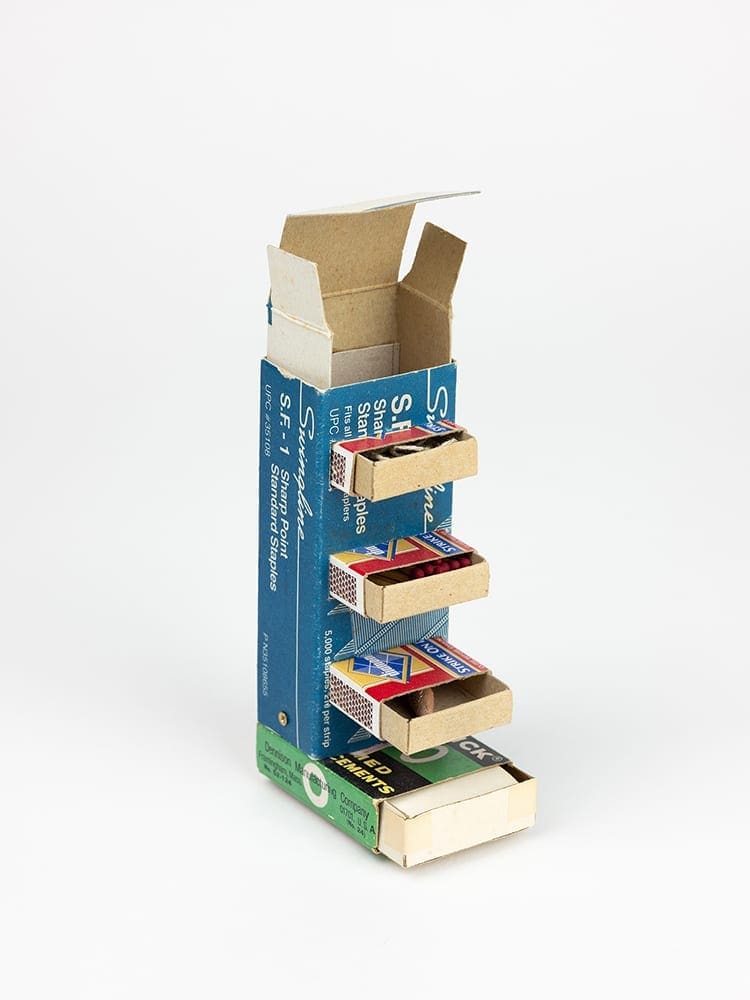

Miniature Cabinet. Made from matchboxes and office-supply boxes by Liz Lester of Fayetteville, 2019. Courtesy Liz Lester

Liz Lester, Fayetteville

Liz is a life-long illustrator who began making constructions out of found items beginning about 2004. Witnessing the rapid growth of an industrial landfill during walks through a nearby neighborhood inspired the thought, “let’s not pitch any more than we have to in that hole.” She’s especially drawn to boxes and containers, including Altoids® breath-mint tins, which she has transformed into little holiday gifts for friends.

Beth Lowrey

Cabinet. Drawers made from paint-thinner cans by Beth Lowery of Fayetteville, about 1998, and used by Liz Lester for seed storage. Courtesy Liz Lester

Beth Lowrey, Fayetteville

Beth is a woodworker who began turning old objects into new in the late 1990s, after having saved a collection of used paint-thinner cans because they seemed useful. One day she saw their potential as cabinet drawers. Since then she has turned a paint can into a birdhouse, broken dishes into stepping stones, and a torn-apart chest of drawers found in an alley into a new chest of drawers, using old tin-ceiling tiles as side panels. Sometimes she’s inspired by the material, other times an idea sends her to her collection of saved bits and pieces.

Cardi B. Ord

Stool. Made from cardboard boxes and paperboard pads and corner inserts by Cardi B. Ord of Bentonville, 2020. Courtesy M. DemOpp

Cardi B. Ord, Bentonville

Cardi has been making objects for home, work, and friends her entire life, from macaroni “pictures” in Kindergarten to a fern stand made from tree branches and a teddy bear sewn from men’s suiting fabric, which itself was first reused as part of a (now tattered) quilt. She’s also a long-time recycler, beginning in 1970 when her Brownie troop participated in a newspaper drive during the first Earth Day celebration. Her crafting and recycling interests mean that her home workshop is full of odds and ends that she’s saved over the years, just waiting for a chance to shine.

Kathryn A. Sampson Stinson

Tote Bag. Crocheted from plastic grocery bags and newspaper sleeves by Kathryn A. Sampson Stinson of Fayetteville, 2020. The balls of “plarn” (plastic yarn) are made by chaining together strips of plastic. About 105 white bags and 57 yellow sleeves were used to make this tote bag. Courtesy Kathryn A. Sampson Stinson

Kathryn A. Sampson Stinson, Fayetteville

Kathryn’s grandmother taught her how to crochet in the late 1970s. She began working with “plarn” (plastic yarn) in 2011, when she was inspired to make ground mats for use by folks sleeping in shelters and tents. Making them was a bit challenging, so she turned to tote bags. She thinks of her work as a combination of craft project, public service, and environmental responsibility.

Making Do Then, Upcyling Now

Log Cabin

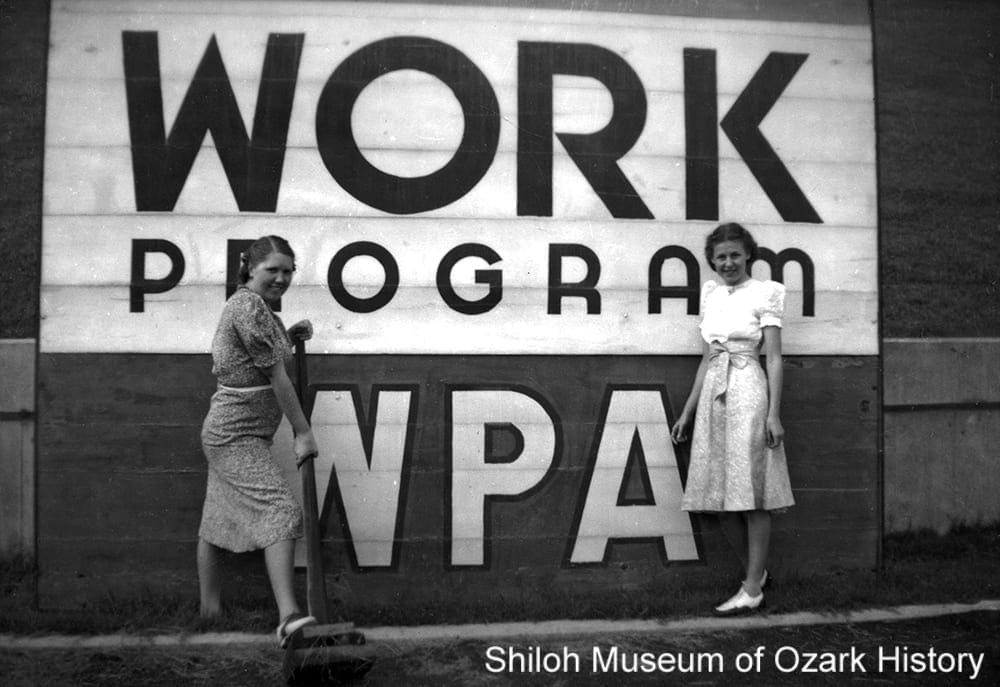

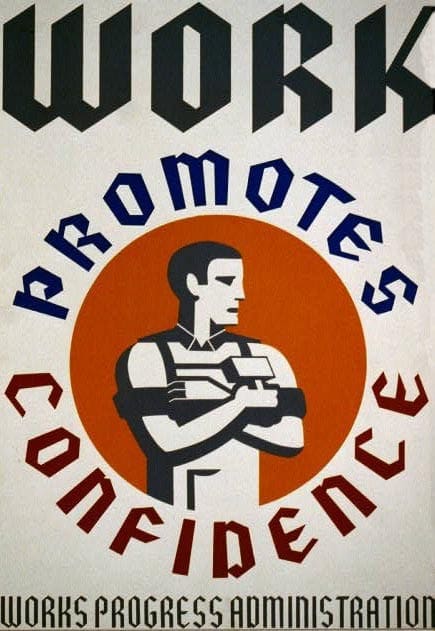

Argie Cooksey and her daughter Ivis pose by their home, possibly near Murray (Newton County), about 1935. Mrs. Cooksey and another woman were said to have cut the trees, hewed (shaped) the logs, and made the boards. The image was made by Ernest & Opal Nicholson who served as county administrators of a Works Progress Administration rural-relief program during the Great Depression. Ernest and Opal Nicholson, photographers. Katie McCoy Collection (S-95-181-84)

Clubhouse

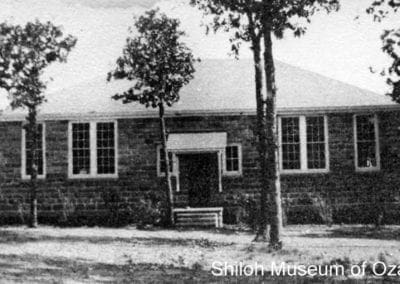

Members of the Minervian Home Demonstration Club stand by their clubhouse on the J. Oscar and Ada M. Wilmoth farm, between Rogers and Monte Ne, about 1935. Home demonstration clubs were part of a national program to teach rural farm women improved methods of gardening, canning, sewing, and nutrition. In order to purchase building supplies, the Minervians held weekly bake sales in downtown Rogers. They and their children gathered field rocks for the building’s exterior while their husbands handled its construction. Courtesy Rogers Historical Museum

Home

Dustin and April Griffith’s shipping-container home, Eureka Springs, 2020. The initial structure was built from 2013 to 2015, using three containers. Three more have since been added. Other repurposed materials include a foundation made of oil barrels pulled from a farmer’s field, roof trusses from a chicken house, a chandelier made from copper pipe, coat hooks made from forks and spoons, and a few specialty windows, including one made from wine bottles and another made from the rear window of a Model T truck (placed over the front door). April Griffith, photographer.

Make a Box

Want to make a small box out of a cereal, cracker, or soda box? Download this template and watch our short video to learn what simple materials and techniques are needed. Have fun being an upcycler!