Settling the Ozarks

Settling the Ozarks

Online ExhibitEMIGRATION.

Near 200 emigrants came up [to Little Rock via the Arkansas River] during the past week, in the steam-boats Industry and Waverly, and we understand several boats are on the river, filled with movers. . . . the mass of the movers are bound for Washington and Crawford counties, and the county acquired from the Cherokees, by the late Treaty. . . . [T]he influx of settlers from Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and other states east of the Mississippi river, and from Missouri, on the north, appears to be daily increasing. That country appears to have acquired much fame abroad . . . For fertility of soil, salubrity of climate, and fine, healthy situations, it is said not to be exceeded by any country. Some of the settlements are already quite dense, and present appearances justify the belief that it will, in a very short period, become the most populous section of our Territory.

Arkansas Gazette, February 2, 1830

A large tract of land including what is now Northwest Arkansas was for a time the hunting grounds of the Osage Indians. Later it was the home of the Cherokee on their forced move westward. In an effort to keep the peace between the tribes, land purchases were made and boundaries redrawn. But the settlers and politicians of the Arkansas Territory wanted the fertile valleys and timbered lands for themselves.

In the 1820s the Arkansas Territorial government opened the lands to white settlement. Meanwhile the Federal government passed laws to keep them closed. Throughout this wrangling, folks came, joining the squatters who had come earlier. All homesteaded under the sometimes realized threat of eviction. But by 1829 the land was opened officially for settlement.

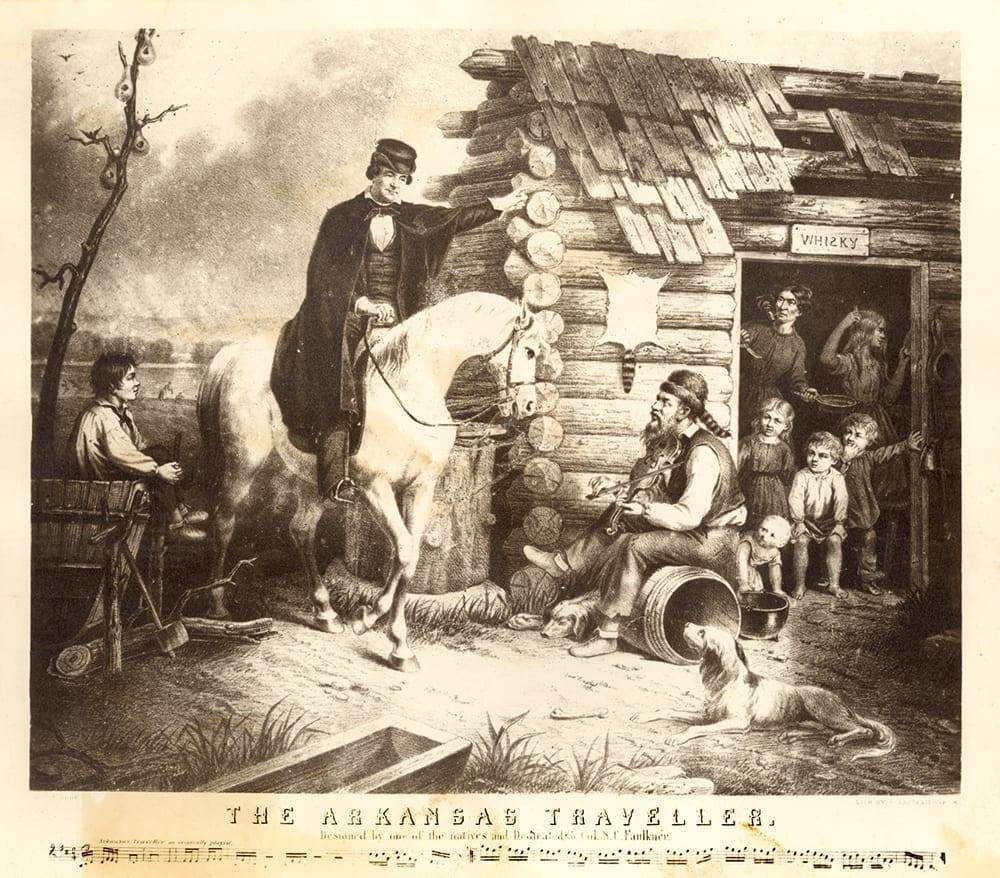

These early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a plot of land to call their own.

They came in ox-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They traveled as far as the river could take them and then journeyed overland to reach their new home, hacking out paths through forested mountains and valleys or following rough military roads. Not all settlers came of their own free will. Some were enslaved Africans and African Americans. They too played a large role in settling the Ozarks.

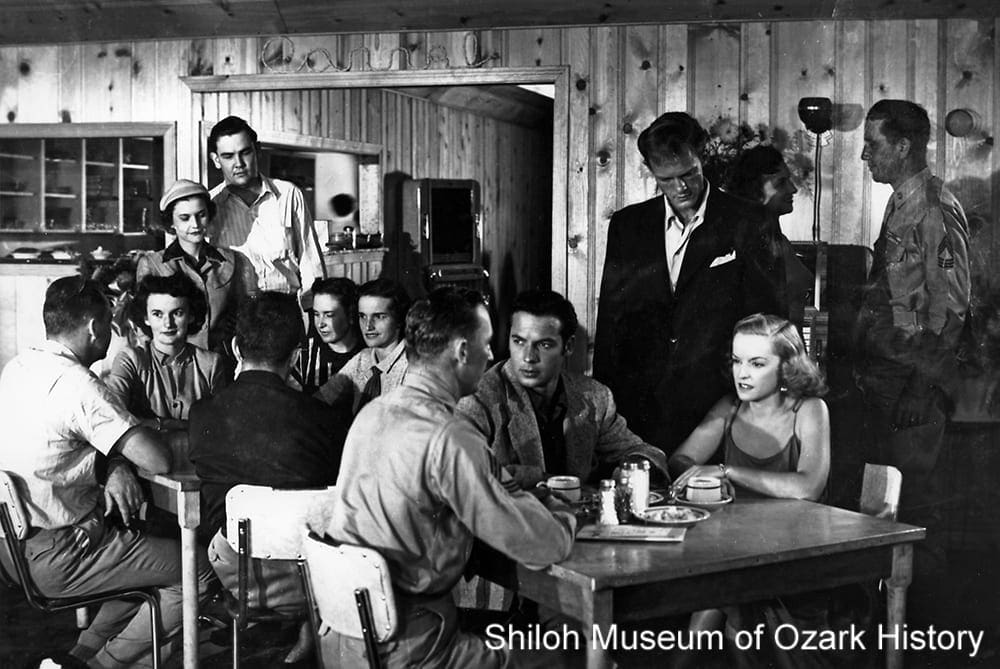

Harvesting wheat, Kingston area (Madison County), early 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Bouher Family Collection (S-2001-2-94)

The first settlers chose the best property—flat, fertile bottom lands or prairies near a river or spring, but within easy reach of the forest. James Preston Neal was nine years old when his family traveled from Kentucky to Cane Hill (Washington County) in 1829. His stepfather, the Reverend Andrew “Uncle Buck” Buchanan, spied a nice piece of land with a spring on it, only to find that it was already claimed. The hunter who had the property offered to give it to Uncle Buck provided two conditions were met. First, that the hunter could find another good spring for himself, and second, that Uncle Buck would preach two good sermons. The deal was made.

Folks with money bought “improved” lands, cleared and ready for farming, or unimproved government land at a lower price. Those without money became squatters, taking over a piece of land, improving it, and hoping to someday buy it outright. Sometimes claim jumpers bought their land, forcing the squatters to buy it back or move on. Later on, the Homestead Act of 1862 allowed many U.S. citizens the right to claim 160 acres of public land provided they began living on it and improving it within six months. After five years, if they had met the improvement requirements, they received title to the land.

Settlers came with their extended family or joined relatives already on the frontier. It was more important to settle near kinfolk than on the best available land. Kin could help with big chores like clearing land or harvesting crops as well as aid families in overcoming hardships. Early farm families were often large in number to help with the heavy workload. And chores couldn’t wait. Crops had to be planted, food harvested, and cows milked at the proper time.

Over the years change came to Northwest Arkansas. Communities grew, businesses started, transportation improved, labor-saving tools were invented, educational opportunities expanded, and new folks coming from the North or from overseas. But the area remained largely rural and agricultural well into the 20th century. Families stayed together, farming the same land as their ancestors and taking pride in their self-reliance and self-sufficiency. The land was theirs and they knew how to live on it.

A large tract of land including what is now Northwest Arkansas was for a time the hunting grounds of the Osage Indians. Later it was the home of the Cherokee on their forced move westward. In an effort to keep the peace between the tribes, land purchases were made and boundaries redrawn. But the settlers and politicians of the Arkansas Territory wanted the fertile valleys and timbered lands for themselves.

Harvesting wheat, Kingston area (Madison County), early 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Bouher Family Collection (S-2001-2-94)

In the 1820s the Arkansas Territorial government opened the lands to white settlement. Meanwhile the Federal government passed laws to keep them closed. Throughout this wrangling, folks came, joining the squatters who had come earlier. All homesteaded under the sometimes realized threat of eviction. But by 1829 the land was opened officially for settlement.

These early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a plot of land to call their own.

They came in ox-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They traveled as far as the river could take them and then journeyed overland to reach their new home, hacking out paths through forested mountains and valleys or following rough military roads. Not all settlers came of their own free will. Some were enslaved Africans and African Americans. They too played a large role in settling the Ozarks.

The first settlers chose the best property—flat, fertile bottom lands or prairies near a river or spring, but within easy reach of the forest. James Preston Neal was nine years old when his family traveled from Kentucky to Cane Hill (Washington County) in 1829. His stepfather, the Reverend Andrew “Uncle Buck” Buchanan, spied a nice piece of land with a spring on it, only to find that it was already claimed. The hunter who had the property offered to give it to Uncle Buck provided two conditions were met. First, that the hunter could find another good spring for himself, and second, that Uncle Buck would preach two good sermons. The deal was made.

Folks with money bought “improved” lands, cleared and ready for farming, or unimproved government land at a lower price. Those without money became squatters, taking over a piece of land, improving it, and hoping to someday buy it outright. Sometimes claim jumpers bought their land, forcing the squatters to buy it back or move on. Later on, the Homestead Act of 1862 allowed many U.S. citizens the right to claim 160 acres of public land provided they began living on it and improving it within six months. After five years, if they had met the improvement requirements, they received title to the land.

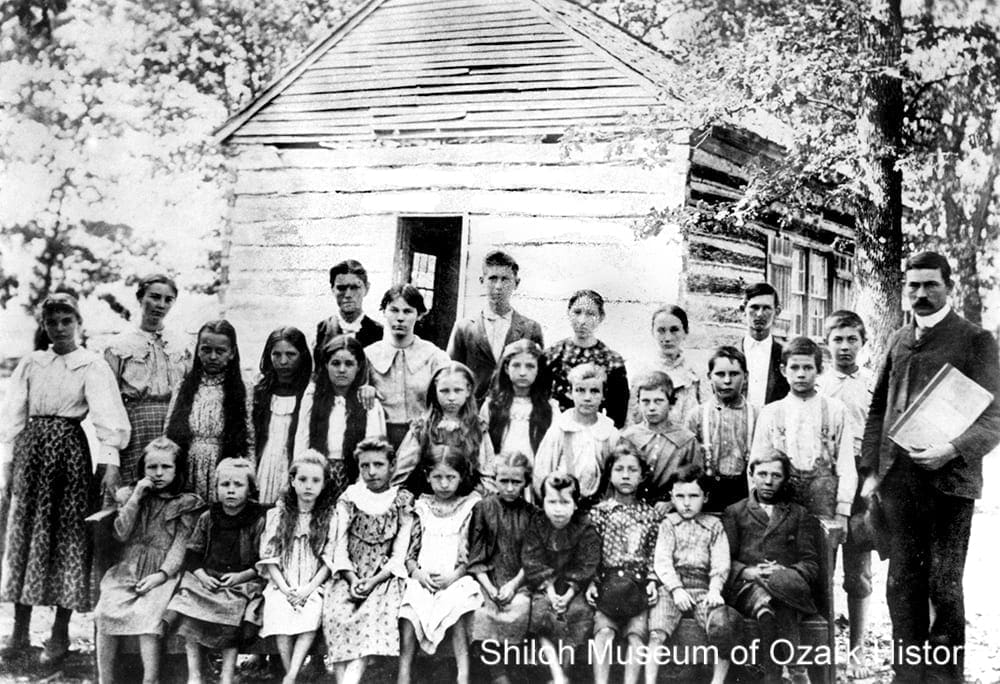

Settlers came with their extended family or joined relatives already on the frontier. It was more important to settle near kinfolk than on the best available land. Kin could help with big chores like clearing land or harvesting crops as well as aid families in overcoming hardships. Early farm families were often large in number to help with the heavy workload. And chores couldn’t wait. Crops had to be planted, food harvested, and cows milked at the proper time.

Over the years change came to Northwest Arkansas. Communities grew, businesses started, transportation improved, labor-saving tools were invented, educational opportunities expanded, and new folks coming from the North or from overseas. But the area remained largely rural and agricultural well into the 20th century. Families stayed together, farming the same land as their ancestors and taking pride in their self-reliance and self-sufficiency. The land was theirs and they knew how to live on it.

Creating a Home

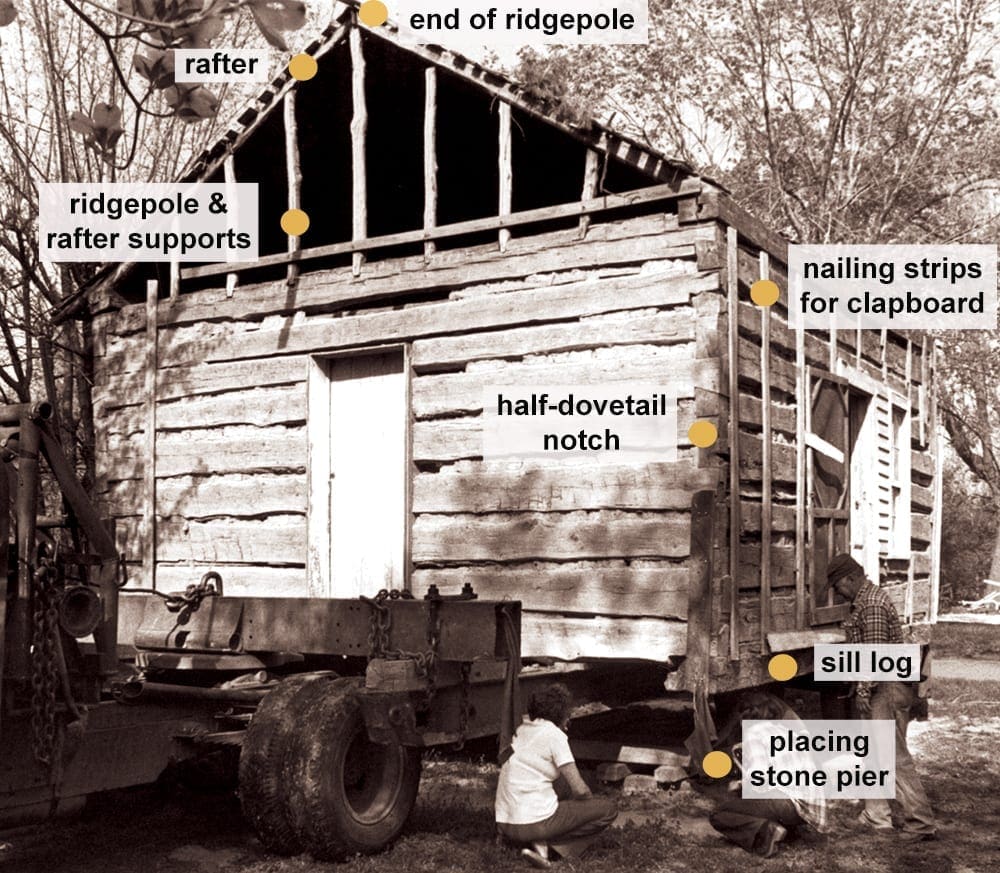

Settlers could bring only a limited amount of textiles, tools, furniture, and household goods with them. When they got to their new homestead they had to make nearly everything for themselves, including a house in which to live.

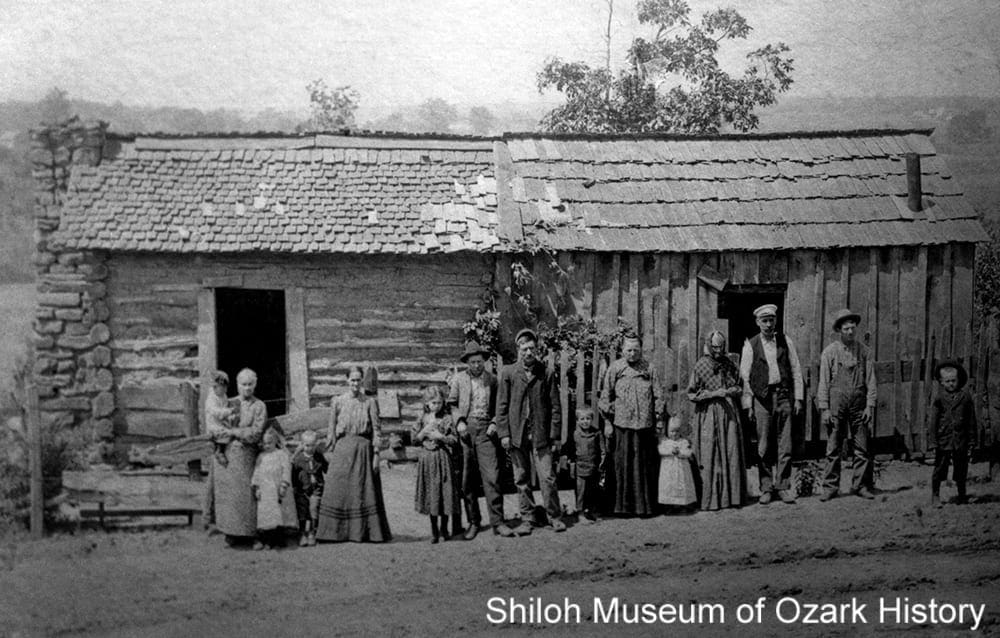

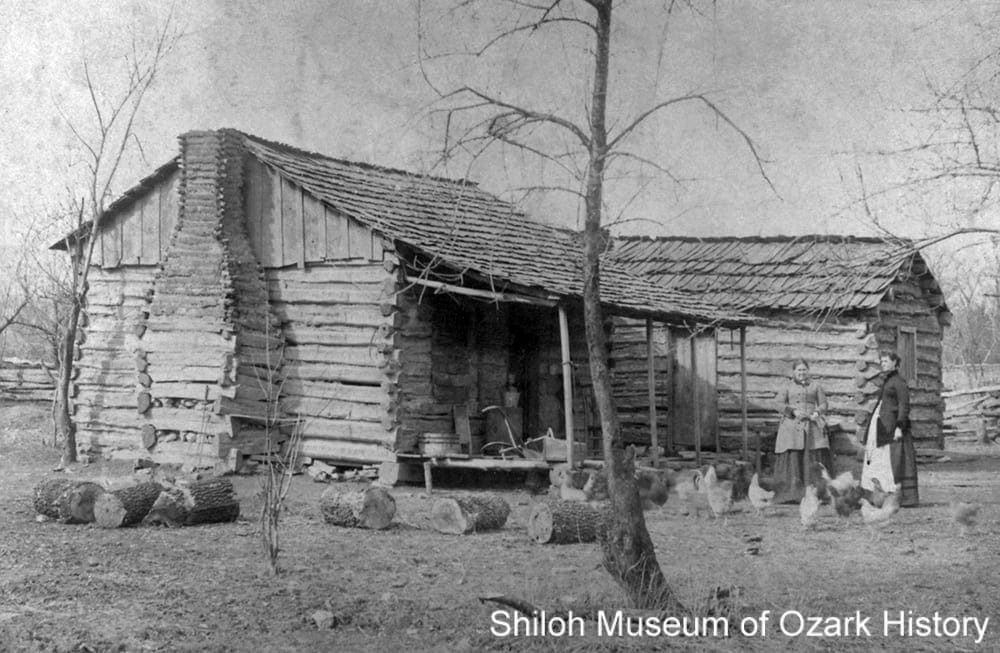

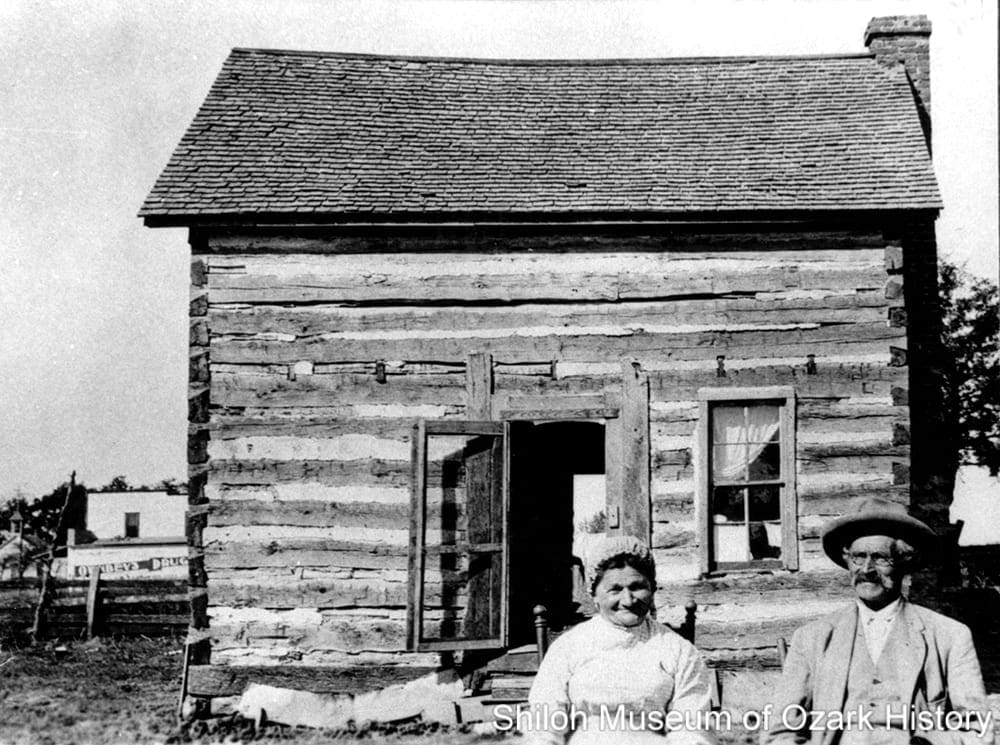

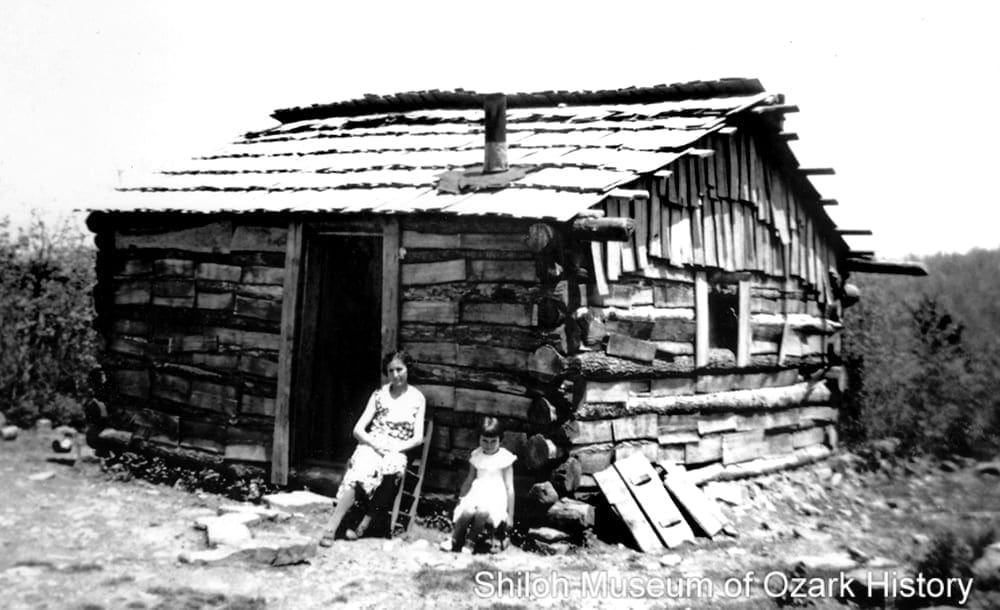

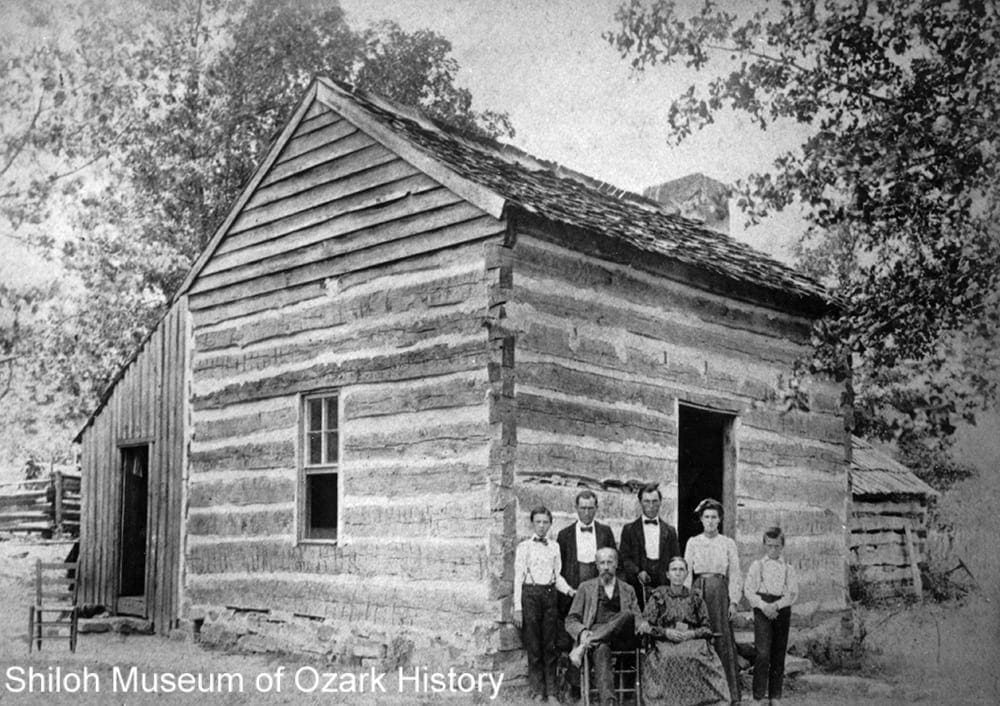

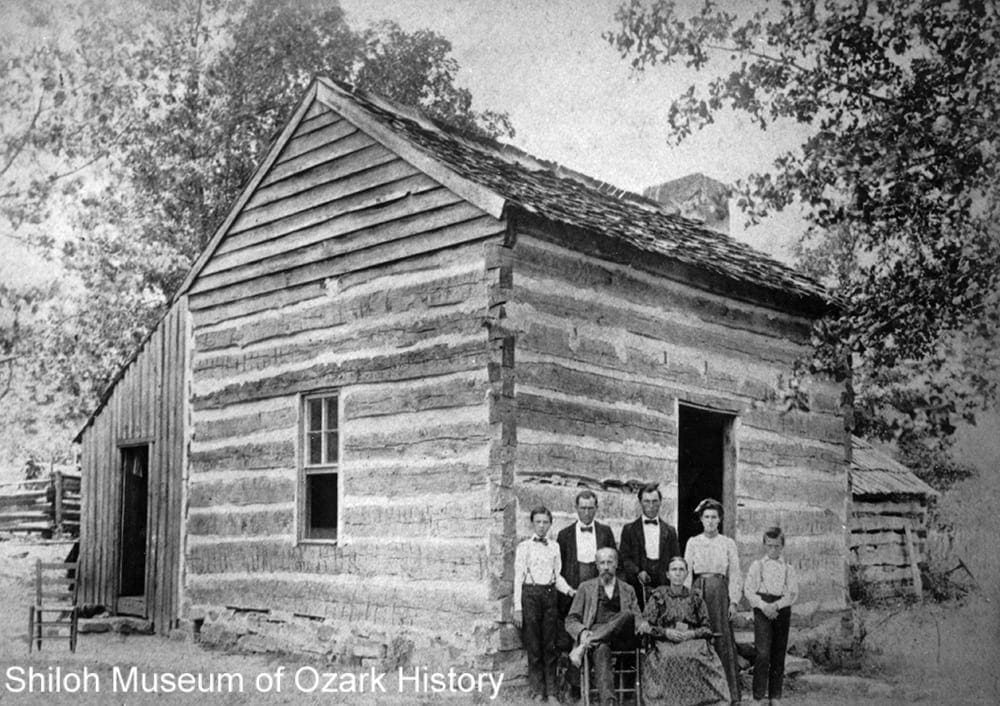

The James S. and Ann Eliza Counts McDonald family, Thorney (Madison County), about 1900. Some families, even as they prospered, continued to live in their old log cabins, adding on as needed. Gary King Collection (S-97-2-135)

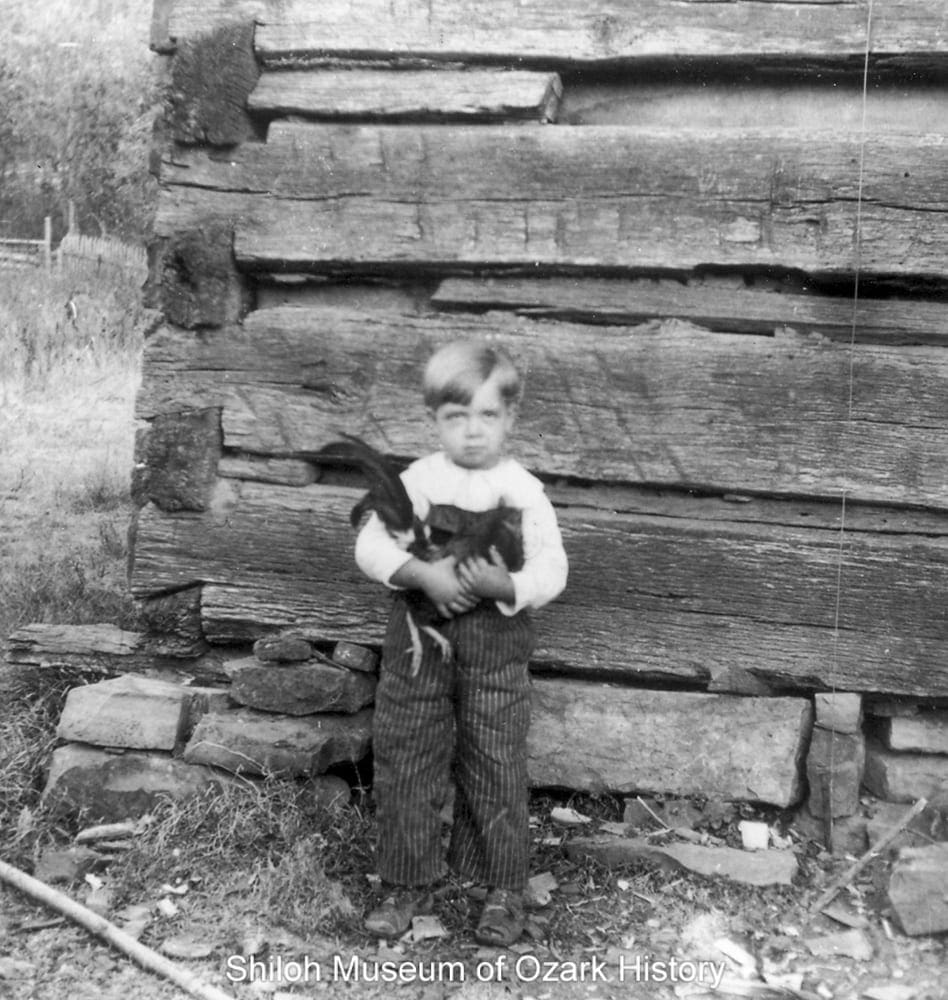

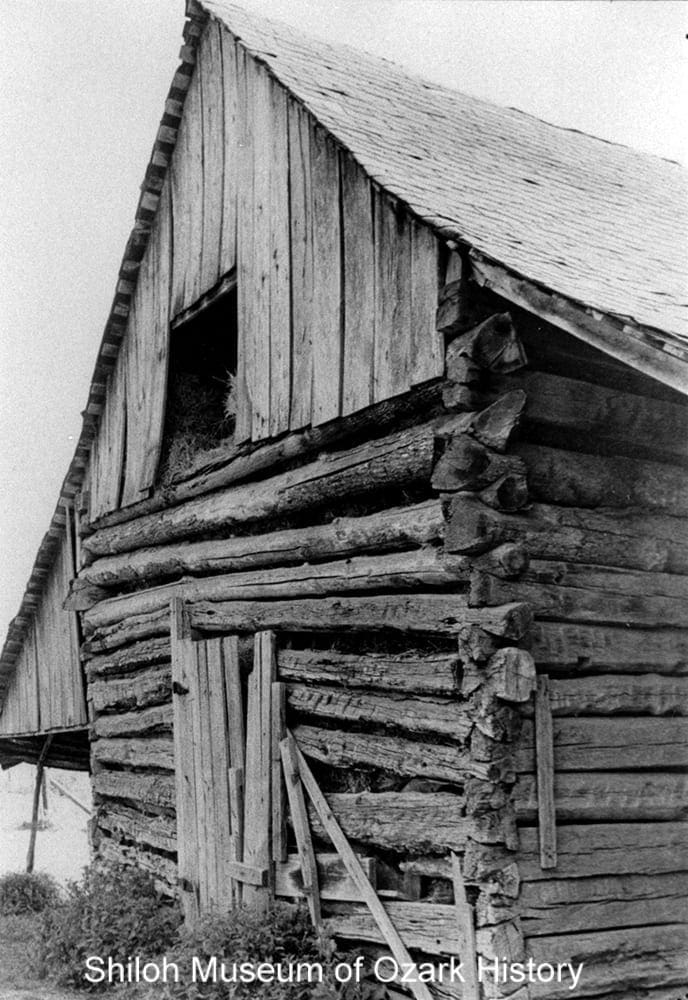

Home. The settler’s first permanent shelter was often a small, square, notched-log structure. Home building was a community affair. Many workers were needed to lift the logs in place. While the heavy work was going on, the woman of the house, and maybe some of the other women, prepared a big dinner, laying out a spread of ham, cornbread, salads, pies, and other tasty foods. Good food, fiddle music, and dancing made house-raising a fun event.

Tools and Household Goods. If a family didn’t bring chairs or benches with them, primitive versions were made from split logs and tree limbs. A puncheon bed made of thick slabs of wood resting on a frame was partially embedded into a corner of the log cabin as it was being built; a post held up the unattached corner. Rope beds used a network of cording crisscrossed through a frame. The rope sagged over time and required retightening, giving meaning to the phrase, “Sleep tight, don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

Wood was fashioned into tableware such as spoons, bowls, and trenchers (plates). Tools and equipment such as yokes for oxen, rakes, and axe handles were made of wood, but the axe head and other metal implements had to be purchased elsewhere. Split-oak strips were woven into baskets and water dippers were made from dried gourds. Cord and shoelaces could be made from strips of rawhide or tanned leather. John Ed Watkins, born in 1854 to early settlers of the upper Crooked Creek Valley (Boone County), recounted that pawpaw bark was used for such things as woven chair seats and bed ropes, and for tying up minnow seines (fish nets).

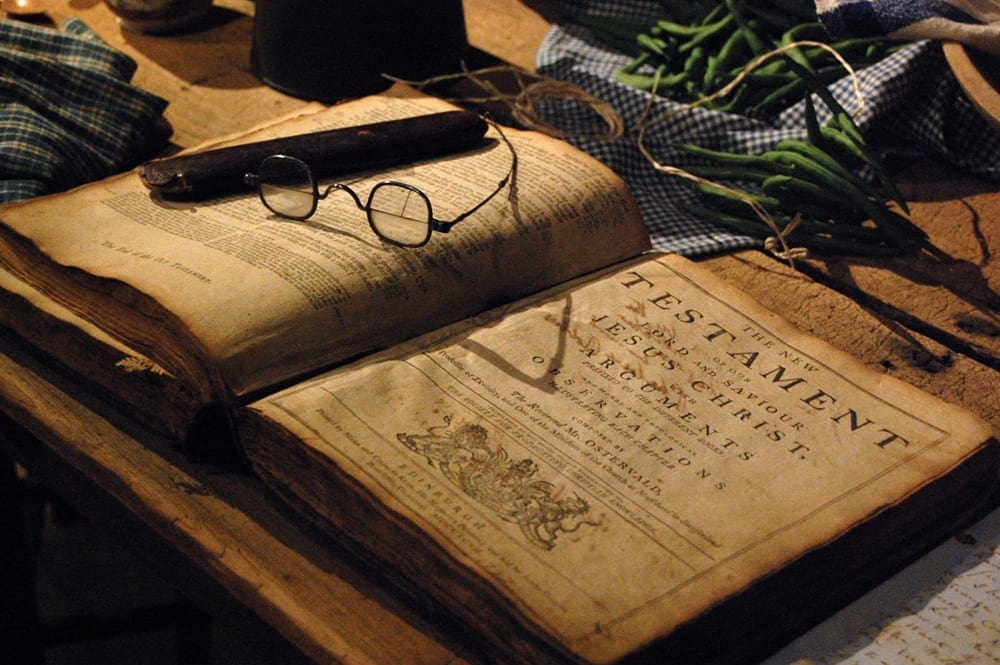

Lighting. Most of a family’s work was done during daylight hours. Although a fireplace provided some light, it wasn’t enough for reading or task work. Grease lamps were common. A loosely twisted cotton rag or homemade cotton wick was placed in a saucer, hollowed-out stone, or even a turtle shell filled with hog or bear grease. When the exposed part of the wick was lit, it gave a weak light. Good light could be had by burning pine knots, hard, resinous pieces of wood. Tallow candles were made if the family had beef or mutton fat and a metal mold, or took the time to dip wicks repeatedly into liquid animal fat or beeswax. Candles were often saved for special occasions like holidays or visits from the preacher.

Clothing and Textiles. Some of the earliest settlers wore shirts and breeches made from tanned animal skins. Cloth was used for most clothing and was usually made at home. Ready-made cloth like cotton calico and fancy wool suiting was expensive on the frontier. Cotton and flax (for linen) were planted and sheep raised for their wool. The resulting fibers were cleaned, carded (combed), and spun into thin threads and heavier yarns. Some yarns were knitted into stockings and scarves. Others were threaded onto a loom and woven into cloth.

Homespun cloth was used for household textiles like blankets, towels, and sheets and for making clothing. Early settlers to Northwest Arkansas repeatedly mentioned “linsey” and “jean.” Linsey was a lightweight fabric made from wool and sometimes linen or cotton. It was used for making dresses and shirts. Jean was a heavy wool cloth used for men’s work clothing. Women cut clothing patterns themselves. If they weren’t a talented tailor or seamstress, the clothes would be ill-fitting—but they were still worn. Clothing took time to make and storage was limited. Folks might have two sets of everyday clothes and a better set for Sundays.

Shoes. Most shoes were made from home-tanned leather made from the hides of deer, hogs, and cattle. Squirrel leather was sometimes used for young children’s shoes. John Ed Watkins recalled that in his youth shoes were sewn together with flax thread rubbed with beeswax and the soles were nailed on with tiny pegs made of maple wood. Boots were worn in the winter. As they wore down, their tops were cut off to make summer plow shoes. Footwear was greased and polished weekly with a mix of pine tar, tallow, and soot. Children usually went barefoot spring, summer, and fall.

Money. Neighbors shared resources such as candle molds and sorghum mills or traded for the things they needed. But sometimes money was necessary to purchase land, pay taxes, or buy special goods like salt, lead for bullets, ready-made fabric, and metal tools. Folks earned money by selling surplus meat and grain, dried apples, deer hides, homespun cloth, lumber, and marketable herbs like ginseng. They also took on short-term jobs like hauling freight. As communities grew, specialty businesses sprung up. Millers ground corn and wheat, tanners cured leather and fashioned shoes, and blacksmiths shod horses and made tools. Washington County led the way in population growth and town building, with fast-growing professional, industrial, and agricultural sectors.

Some Early Settlers

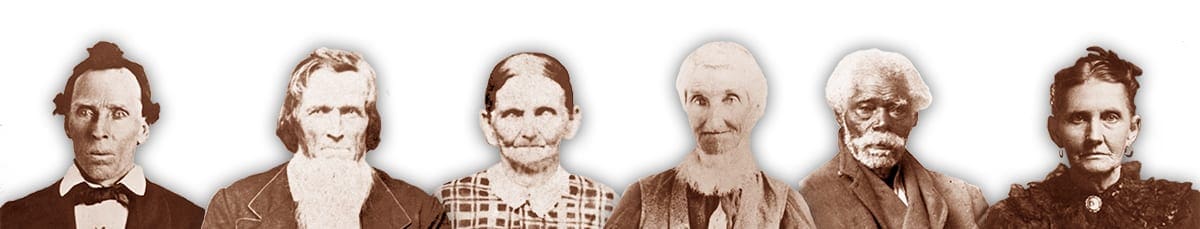

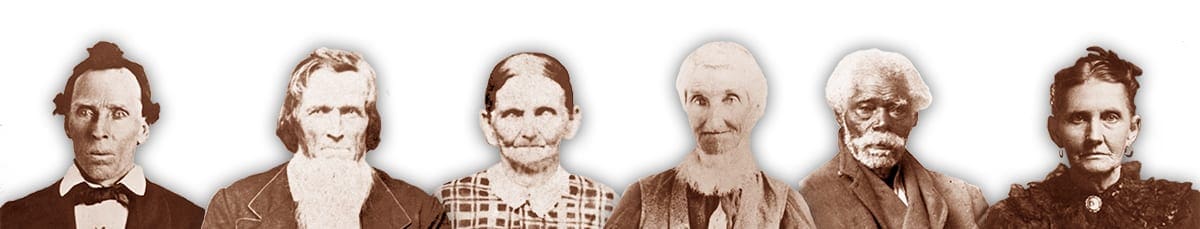

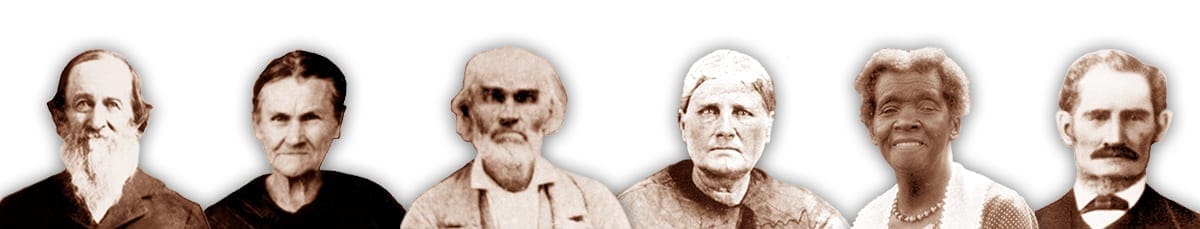

From left:

Jacob A. Meek, 1811–1882. Came to Dry Creek (Carroll County) about 1836 from Tennessee. Farmer, trader, livestock dealer and mayor of Berryville; raised ten children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-236-24)

Sylvanus and Catherine Blackburn, 1809–1890; 1809–1890. Came to War Eagle (Benton County) in 1832 from Tennessee. Ran gristmill, sawmill, blacksmith shop, and carpentry shop; started first school in area; raised nine children and eight adopted children. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-85-323-36)

Jeremiah Combs, 1788–1867. Came to Combs (Madison County) about 1832 from Tennessee. Farmer; raised twelve children. John D. Little Collection (S-84-18-1)

Sam Van Winkle, 1822–1913. Brought to Van Hollow (Benton County) before the Civil War as an enslaved person from Kentucky. Saw mill operator and orchard keeper; raised three children. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-171)

Lucinda Bloyed Karnes, 1840-1915. Born in West Fork (Washington County); her parents came from Kentucky in 1836. Housewife; raised two children and orphaned nephew. Pody Gay Collection (S-2006-26-7)

Creating a Home

James S. and Ann Eliza Counts McDonald family, Thorney (Madison County), about 1900. Some families, even as they prospered, continued to live in their old log cabins, adding on as needed. Gary King Collection (S-97-2-135)

Settlers could bring only a limited amount of textiles, tools, furniture, and household goods with them. When they got to their new homestead they had to make nearly everything for themselves, including a house in which to live.

Home. The settler’s first permanent shelter was often a small, square, notched-log structure. Home building was a community affair. Many workers were needed to lift the logs in place. While the heavy work was going on, the woman of the house, and maybe some of the other women, prepared a big dinner, laying out a spread of ham, cornbread, salads, pies, and other tasty foods. Good food, fiddle music, and dancing made house-raising a fun event.

Tools and Household Goods. If a family didn’t bring chairs or benches with them, primitive versions were made from split logs and tree limbs. A puncheon bed made of thick slabs of wood resting on a frame was partially embedded into a corner of the log cabin as it was being built; a post held up the unattached corner. Rope beds used a network of cording crisscrossed through a frame. The rope sagged over time and required retightening, giving meaning to the phrase, “Sleep tight, don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

Wood was fashioned into tableware such as spoons, bowls, and trenchers (plates). Tools and equipment such as yokes for oxen, rakes, and axe handles were made of wood, but the axe head and other metal implements had to be purchased elsewhere. Split-oak strips were woven into baskets and water dippers were made from dried gourds. Cord and shoelaces could be made from strips of rawhide or tanned leather. John Ed Watkins, born in 1854 to early settlers of the upper Crooked Creek Valley (Boone County), recounted that pawpaw bark was used for such things as woven chair seats and bed ropes, and for tying up minnow seines (fish nets).

Lighting. Most of a family’s work was done during daylight hours. Although a fireplace provided some light, it wasn’t enough for reading or task work. Grease lamps were common. A loosely twisted cotton rag or homemade cotton wick was placed in a saucer, hollowed-out stone, or even a turtle shell filled with hog or bear grease. When the exposed part of the wick was lit, it gave a weak light. Good light could be had by burning pine knots, hard, resinous pieces of wood. Tallow candles were made if the family had beef or mutton fat and a metal mold, or took the time to dip wicks repeatedly into liquid animal fat or beeswax. Candles were often saved for special occasions like holidays or visits from the preacher.

Clothing and Textiles. Some of the earliest settlers wore shirts and breeches made from tanned animal skins. Cloth was used for most clothing and was usually made at home. Ready-made cloth like cotton calico and fancy wool suiting was expensive on the frontier. Cotton and flax (for linen) were planted and sheep raised for their wool. The resulting fibers were cleaned, carded (combed), and spun into thin threads and heavier yarns. Some yarns were knitted into stockings and scarves. Others were threaded onto a loom and woven into cloth.

Homespun cloth was used for household textiles like blankets, towels, and sheets and for making clothing. Early settlers to Northwest Arkansas repeatedly mentioned “linsey” and “jean.” Linsey was a lightweight fabric made from wool and sometimes linen or cotton. It was used for making dresses and shirts. Jean was a heavy wool cloth used for men’s work clothing. Women cut clothing patterns themselves. If they weren’t a talented tailor or seamstress, the clothes would be ill-fitting—but they were still worn. Clothing took time to make and storage was limited. Folks might have two sets of everyday clothes and a better set for Sundays.

Shoes. Most shoes were made from home-tanned leather made from the hides of deer, hogs, and cattle. Squirrel leather was sometimes used for young children’s shoes. John Ed Watkins recalled that in his youth shoes were sewn together with flax thread rubbed with beeswax and the soles were nailed on with tiny pegs made of maple wood. Boots were worn in the winter. As they wore down, their tops were cut off to make summer plow shoes. Footwear was greased and polished weekly with a mix of pine tar, tallow, and soot. Children usually went barefoot spring, summer, and fall.

Money. Neighbors shared resources such as candle molds and sorghum mills or traded for the things they needed. But sometimes money was necessary to purchase land, pay taxes, or buy special goods like salt, lead for bullets, ready-made fabric, and metal tools. Folks earned money by selling surplus meat and grain, dried apples, deer hides, homespun cloth, lumber, and marketable herbs like ginseng. They also took on short-term jobs like hauling freight. As communities grew, specialty businesses sprung up. Millers ground corn and wheat, tanners cured leather and fashioned shoes, and blacksmiths shod horses and made tools. Washington County led the way in population growth and town building, with fast-growing professional, industrial, and agricultural sectors.

Some Early Settlers

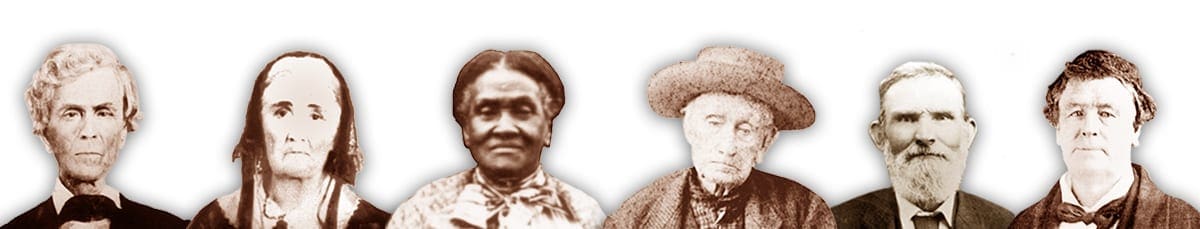

From left:

Jacob A. Meek, 1811–1882. Came to Dry Creek (Carroll County) about 1836 from Tennessee. Farmer, trader, livestock dealer and mayor of Berryville; raised ten children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-236-24)

Sylvanus and Catherine Blackburn, 1809–1890; 1809–1890. Came to War Eagle (Benton County) in 1832 from Tennessee. Ran gristmill, sawmill, blacksmith shop, and carpentry shop; started first school in area; raised nine children and eight adopted children. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-85-323-36)

Jeremiah Combs, 1788–1867. Came to Combs (Madison County) about 1832 from Tennessee. Farmer; raised twelve children. John D. Little Collection (S-84-18-1)

Sam Van Winkle, 1822–1913. Brought to Van Hollow (Benton County) before the Civil War as an enslaved person from Kentucky. Saw mill operator and orchard keeper; raised three children. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-171)

Lucinda Bloyed Karnes, 1840-1915. Born in West Fork (Washington County); her parents came from Kentucky in 1836. Housewife; raised two children and orphaned nephew. Pody Gay Collection (S-2006-26-7)

Growing and Gathering Food

Most of a family’s energy and resources went into food production and food preservation for themselves and for their livestock. Each homestead produced a variety of crops, hedging their bets against a catastrophic crop failure and ensuring a wide range of nutrients for their diet.

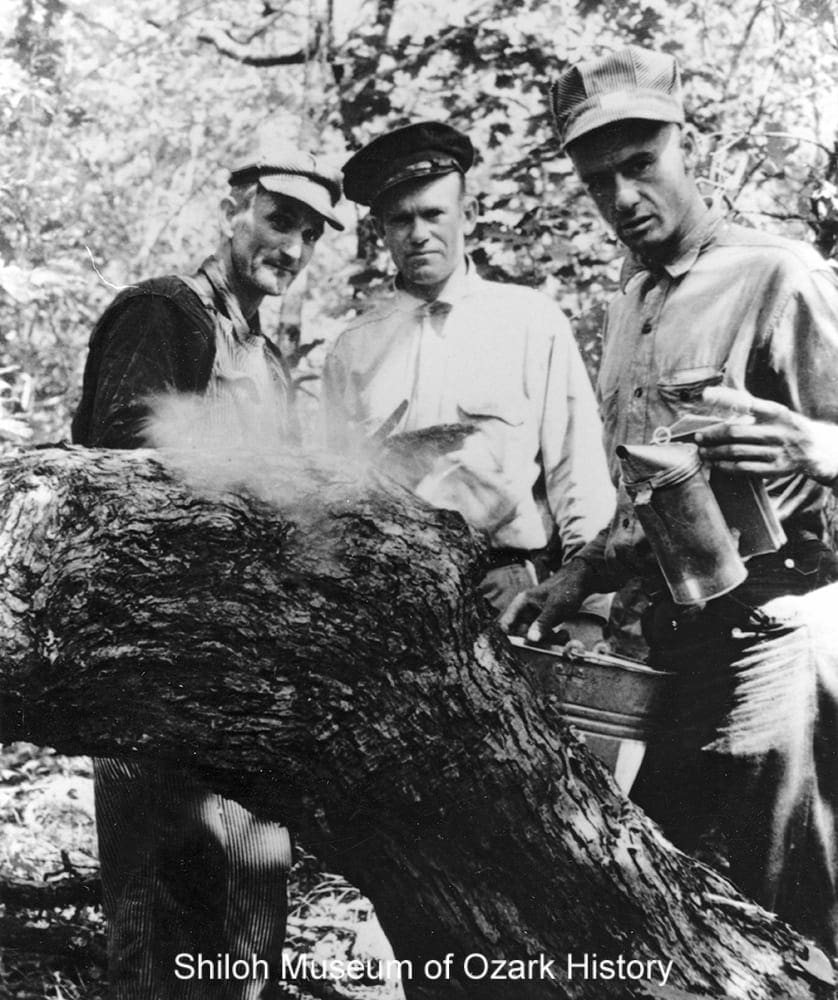

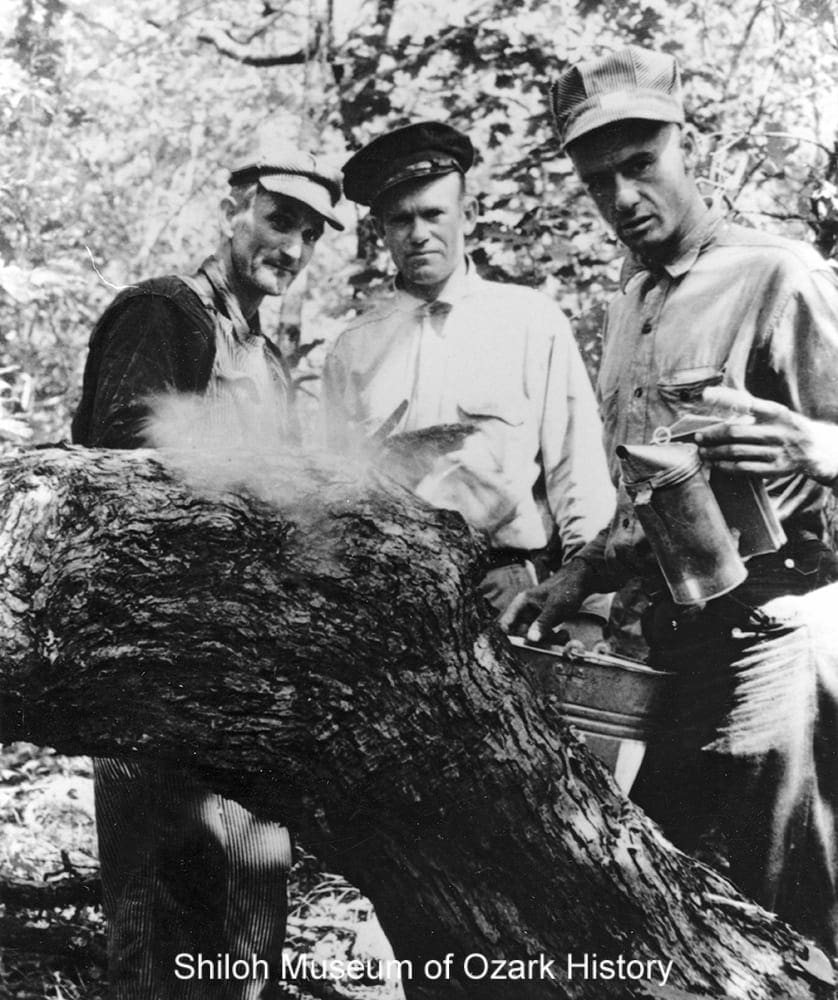

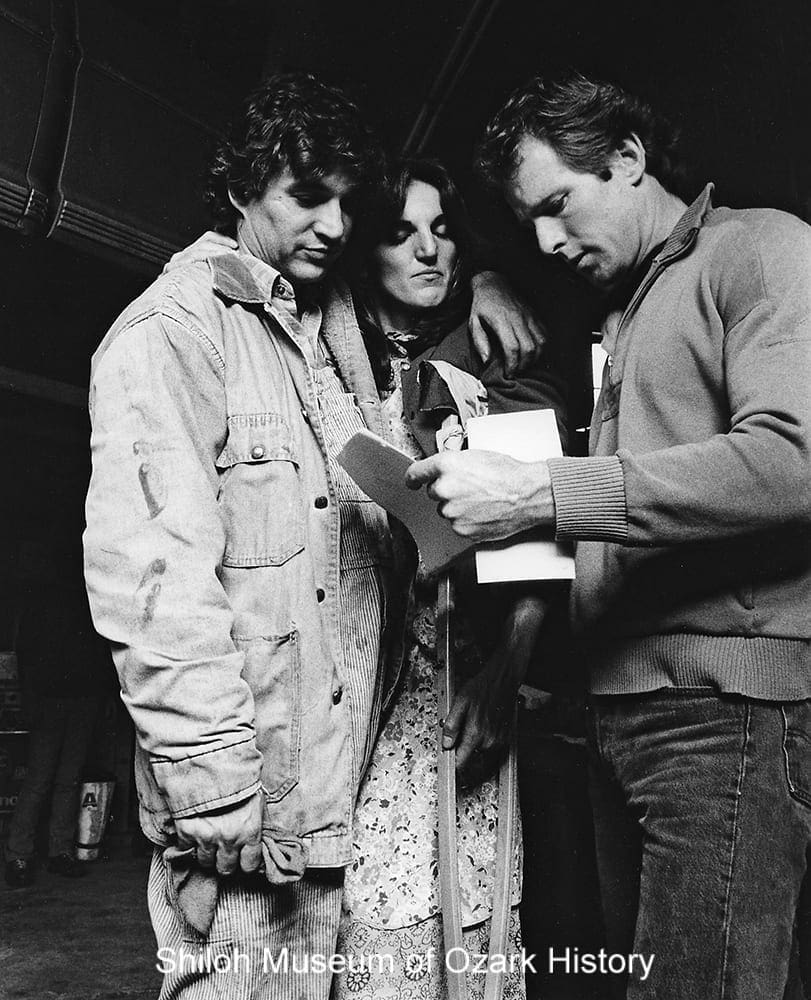

Using smoke to calm bees at a bee tree, Madison County, circa 1939. From left: Nuell Stepp, John Acord, and Joe Acord. Bob Eaton, photographer. Alice Martin Collection (S-2006-31-2)

Gathering Food. Soon after the settlers came they hunted, trapped, and fished for meat to allow their livestock and crops time to grow. Deer, turkeys, squirrels, and rabbits were often targeted, but quail, prairie chickens, opossums, raccoons, wild hogs, and even the occasional bear found their way into the stewpot. Game was usually eaten fresh as it didn’t lend itself to long-term preservation.

Blackberries, huckleberries, walnuts, persimmons, pawpaws (sometimes called Arkansas bananas), gooseberries, wild onion and garlic, sarvis (service) berries, wild crab apples, summer grapes, and chinquapin, hazel, and hickory nuts were gathered from the fields and forests. Greens such as poke sallet, narrowleaf dock, lamb’s quarters, plantain, water cress, hog weed, and wild mustard were important sources of vitamins and minerals. The resin from the sweet gum tree was used as chewing gum.

Wild bees were followed to their hive in the hollow of a tree. Settlers carved an “X” on the “bee tree” to claim it. Or they might relocate the bees to a “bee gum,” a homemade hive made from an upright hollow log threaded with crossed sticks and capped with a lid. Bees were important for their honey and wax and for their ability to pollinate plants.

Maple trees were tapped in early spring as their sap rose. A hole was bored in the trunk and a small piece of hollow river cane was used to funnel the clear liquid into a bucket. Hours of boiling rendered syrup; further boiling produced a thick paste that, when cooled, hardened into a sugar-like consistency.

Growing Food. Corn was the mainstay of the diet, both for people and livestock; acres were devoted to it. Sorghum was grown for the molasses that could be made from it. Other fruits and vegetables were raised in the home garden and orchard. Apples, sweet potatoes and Irish (white) potatoes, watermelons, beans, cabbages, turnips, peaches, peas, collard and mustard greens, pumpkins, and squash were carefully tended. A portion of the crop was allowed to go to seed, to be saved and planted the next year. In the fall, seed potatoes were placed in a straw-lined hole in the ground to keep them insulated from freezing weather.

Easy-to-keep hogs and chickens were the most common livestock on the farm. In the 1840 census of Washington County, 36,000 hogs and 10,000 chickens were counted; there were 7,148 residents. Most animals offered more than their meat. Cowhide was turned into leather while the animal’s milk was churned into butter. Hog fat was rendered into lard and sheep were sheared for their wool. Chickens, geese, and ducks produced eggs and their feathers were used to stuff pillows and mattresses.

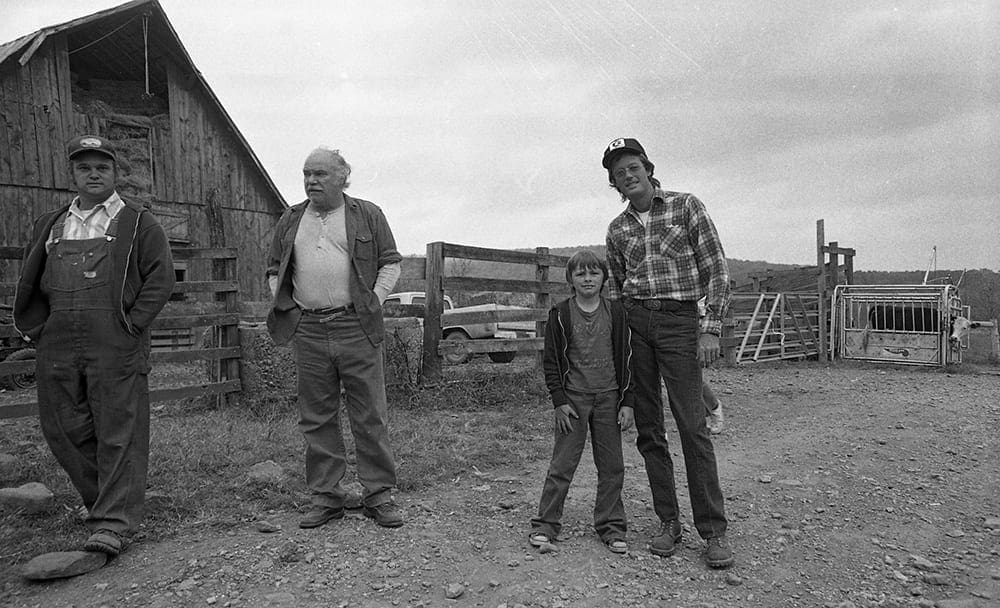

Uncovering seed potatoes for spring planting, Pettigrew (Madison County), 1940. From left: Boyd Bennett, Otto Bennett, and Oscar Bennett. Otto Bennett Collection (S-99-66-760)

Purchasing Food. Most merchandise traveled the same paths as did the settlers—shipped by river and then hauled by wagon to major settlements. One common route was up the Arkansas River to Van Buren. Goods could also be transported on the White River from Jacksonport, Arkansas, or brought down from Springfield, Missouri.

Salt was an important preservative. It was usually purchased, although some settlers were lucky to have on their land natural salt licks, shallow depressions in the ground which filled with brackish (salty) water. A major salt works located west of Fort Smith probably supplied much of the area’s salt. When salt was scarce during the Civil War, families scooped the soil from the smokehouse floor and put it in an ash hopper. Water was poured through and the resulting brine boiled down to extract the salt.

Coffee beans, when available, were purchased green and roasted at home. For families who couldn’t afford the expense of coffee, especially during the Civil War, wheat, cornmeal, or rye was parched (toasted) over a fire and brewed, sometimes with molasses.

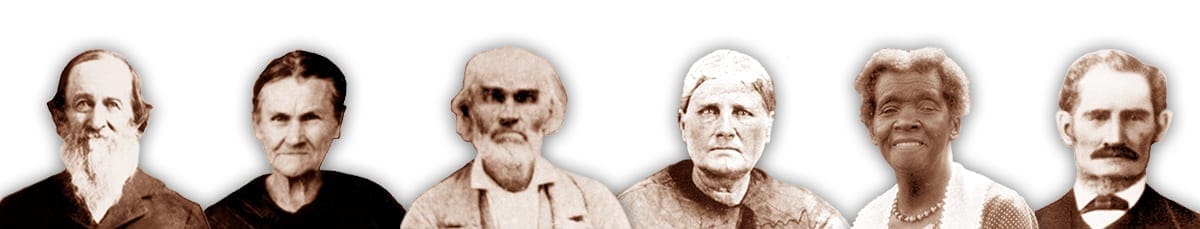

Some Early Settlers

From left:

James O. Nicholson, 1824–1915. Came to Gaither (Boone County) in 1852 from Alabama. Farmer and first merchant in Harrison; raised nine children. Boone County Library/J. W. Nicholson Collection (S-87-38-7)

Nancy Stewart Anderson, 1843–1921. Born near Crosses (Madison County); her parents came from Missouri in the 1840s. Housewife; raised six children. James T. Anderson Collection (S-98-1-140)

John and Dorothea Holcombe, 1797–1876; 1808–1874. Came to West Fork (Washington County) about 1839 from Indiana. Preacher, farmer, and platter of Shiloh (now Springdale); raised sixteen children. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1628) and Susan Chadick Collection (S-2006-175-7)

Adeline Blakely, about 1850–1945. Brought to the Prairie Grove area (Washington County) as an enslaved person about 1852 from Tennessee. Housekeeper. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1679)

Blackburn H. Berry,1814-1893. Came to Berryville (Carroll County) in 1848 from Alabama. Preacher, merchant, and co-founder of Berryville; raised over eighteen children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-18-10)

Growing and Gathering Food

Using smoke to calm bees at a bee tree, Madison County, circa 1939. From left: Nuell Stepp, John Acord, and Joe Acord. Bob Eaton, photographer. Alice Martin Collection (S-2006-31-2)

Most of a family’s energy and resources went into food production and food preservation for themselves and for their livestock. Each homestead produced a variety of crops, hedging their bets against a catastrophic crop failure and ensuring a wide range of nutrients for their diet.

Gathering Food. Soon after the settlers came they hunted, trapped, and fished for meat to allow their livestock and crops time to grow. Deer, turkeys, squirrels, and rabbits were often targeted, but quail, prairie chickens, opossums, raccoons, wild hogs, and even the occasional bear found their way into the stewpot. Game was usually eaten fresh as it didn’t lend itself to long-term preservation.

Blackberries, huckleberries, walnuts, persimmons, pawpaws (sometimes called Arkansas bananas), gooseberries, wild onion and garlic, sarvis (service) berries, wild crab apples, summer grapes, and chinquapin, hazel, and hickory nuts were gathered from the fields and forests. Greens such as poke sallet, narrowleaf dock, lamb’s quarters, plantain, water cress, hog weed, and wild mustard were important sources of vitamins and minerals. The resin from the sweet gum tree was used as chewing gum.

Wild bees were followed to their hive in the hollow of a tree. Settlers carved an “X” on the “bee tree” to claim it. Or they might relocate the bees to a “bee gum,” a homemade hive made from an upright hollow log threaded with crossed sticks and capped with a lid. Bees were important for their honey and wax and for their ability to pollinate plants.

Maple trees were tapped in early spring as their sap rose. A hole was bored in the trunk and a small piece of hollow river cane was used to funnel the clear liquid into a bucket. Hours of boiling rendered syrup; further boiling produced a thick paste that, when cooled, hardened into a sugar-like consistency.

Growing Food. Corn was the mainstay of the diet, both for people and livestock; acres were devoted to it. Sorghum was grown for the molasses that could be made from it. Other fruits and vegetables were raised in the home garden and orchard. Apples, sweet potatoes and Irish (white) potatoes, watermelons, beans, cabbages, turnips, peaches, peas, collard and mustard greens, pumpkins, and squash were carefully tended. A portion of the crop was allowed to go to seed, to be saved and planted the next year. In the fall, seed potatoes were placed in a straw-lined hole in the ground to keep them insulated from freezing weather.

Easy-to-keep hogs and chickens were the most common livestock on the farm. In the 1840 census of Washington County, 36,000 hogs and 10,000 chickens were counted; there were 7,148 residents. Most animals offered more than their meat. Cowhide was turned into leather while the animal’s milk was churned into butter. Hog fat was rendered into lard and sheep were sheared for their wool. Chickens, geese, and ducks produced eggs and their feathers were used to stuff pillows and mattresses.

Uncovering seed potatoes for spring planting, Pettigrew (Madison County), 1940. From left: Boyd Bennett, Otto Bennett, and Oscar Bennett. Otto Bennett Collection (S-99-66-760)

Purchasing Food. Most merchandise traveled the same paths as did the settlers—shipped by river and then hauled by wagon to major settlements. One common route was up the Arkansas River to Van Buren. Goods could also be transported on the White River from Jacksonport, Arkansas, or brought down from Springfield, Missouri.

Salt was an important preservative. It was usually purchased, although some settlers were lucky to have on their land natural salt licks, shallow depressions in the ground which filled with brackish (salty) water. A major salt works located west of Fort Smith probably supplied much of the area’s salt. When salt was scarce during the Civil War, families scooped the soil from the smokehouse floor and put it in an ash hopper. Water was poured through and the resulting brine boiled down to extract the salt.

Coffee beans, when available, were purchased green and roasted at home. For families who couldn’t afford the expense of coffee, especially during the Civil War, wheat, cornmeal, or rye was parched (toasted) over a fire and brewed, sometimes with molasses.

Some Early Settlers

From left:

James O. Nicholson, 1824–1915. Came to Gaither (Boone County) in 1852 from Alabama. Farmer and first merchant in Harrison; raised nine children. Boone County Library/J. W. Nicholson Collection (S-87-38-7)

Nancy Stewart Anderson, 1843–1921. Born near Crosses (Madison County); her parents came from Missouri in the 1840s. Housewife; raised six children. James T. Anderson Collection (S-98-1-140)

John and Dorothea Holcombe, 1797–1876; 1808–1874. Came to West Fork (Washington County) about 1839 from Indiana. Preacher, farmer, and platter of Shiloh (now Springdale); raised sixteen children. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1628) and Susan Chadick Collection (S-2006-175-7)

Adeline Blakely, about 1850–1945. Brought to the Prairie Grove area (Washington County) as an enslaved person about 1852 from Tennessee. Housekeeper. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1679)

Blackburn H. Berry,1814-1893. Came to Berryville (Carroll County) in 1848 from Alabama. Preacher, merchant, and co-founder of Berryville; raised over eighteen children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-18-10)

Preserving and Preparing Food

The food that the settlers grew, gathered, and harvested had to be preserved for the times when fresh food was limited, such as winter. If not enough food was produced, or something went wrong in the preservation process, the family would be in dire straits.

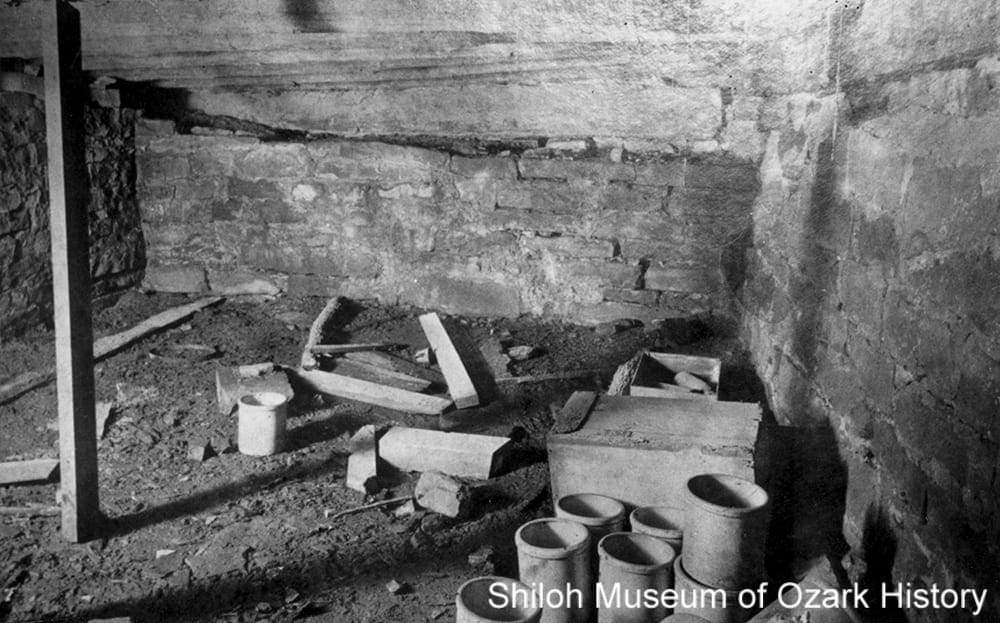

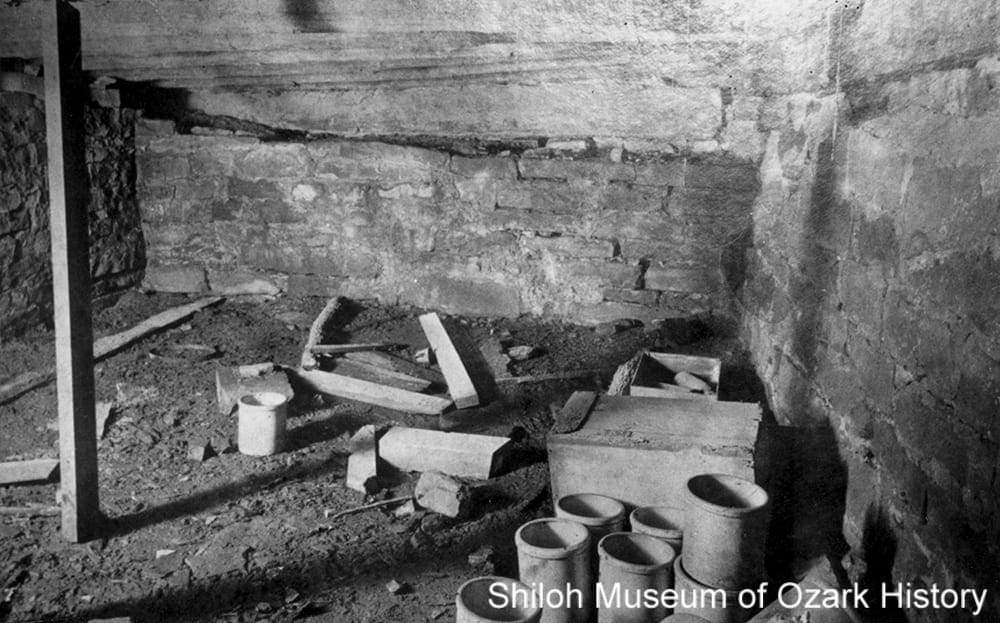

Abandoned cellar with “stone jars,” probably Cane Hill (Washington County), mid 1900s. Mildred Carnahan Collection (S-98-2-685)

Drying. Apples were peeled, quartered, and spread on scaffolds or on a roof and allowed to dry in the hot sun for several days. Pumpkins were sliced into rings and hung by a pole near the fireplace. “Leather britches” were made by drying green beans threaded onto strings. Drying food outside had its dangers, as rain and dew had to be guarded against. If needed, an outdoor stone kiln was built to dry food more quickly.

Corn was usually dried on the ear and often stored in corn cribs, slatted structures with plenty of air circulation. Frank Nance of Madison County, who came with his parents from Kentucky in 1857, said that “grittins” were made by rubbing a semi-dried ear of corn over the rough side of a homemade grater made from a piece of metal punctured with many holes. When needed, corn or wheat was pounded into a flour-like meal at home or at a nearby grist mill.

Cold Storage. The natural insulating and cooling properties of the earth and water were used to preserve foods. “Stone jars” (ceramic crocks) of preserved meat or apple and persimmon butters were kept in root cellars or placed in a springhouse, a small structure built over a natural spring or small creek. Stone-lined cellars or straw-lined holes in the ground held hardy foods like potatoes, apples, pears, turnips, carrots, and cabbages. Sometimes milk and other perishables were lowered in a container or a coarse-fiber tow sack into a well, spring, or creek.

Salting and Smoking. Pork was the only meat that the early settlers were able to preserve long term. The meat was dry-cured, meaning that it was packed in salt for several weeks. As the salt pulls the water out of the meat, it deprives mold and bacteria of moisture. Not only does salt keep meat from spoiling, it also enhances its appearance and improves its texture and flavor. Saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sometimes found in caves, was added to the curing mixture. It helped the meat keep its pink color and improved flavor.

Smoking the meat for several weeks over a small fire of apple or hickory wood adds flavor. More importantly, the compounds in the smoke inhibit or kill microbial growth. If left un-smoked, the meat’s surface fats could go rancid, spoiling the meat and producing an off flavor.

Fermentation and Pickling. Surplus food was turned into beverages or ingredients for food preparation. Corn and fruits were fermented and distilled to make whiskey and fruit brandies, while fermented apple juice was allowed to turn into hard cider. Vinegar was made by boiling apple peels and cores (sometimes adding molasses) and letting the mixture ferment. The microorganisms that cause fermentation release vitamins, making the end product more nutritious.

Cabbage was kept by slicing it thinly and layering it with salt in a stone jar covered with a cloth and weighted down with a plate. The salt released the water in the cabbage creating a brine. The top portion of the cabbage stayed crisp while the bottom turned to sauerkraut. To make headcheese, a meat jelly, the head and feet of a hog were first brined in a salt and vinegar solution and then boiled before the meat was picked off the bones, tied up in a cloth, and allowed to set up until firm.

Mealtime. What did the settlers make with the food they grew, hunted, gathered, and preserved? Nearly every meal featured corn—cornbread, cornpones (water and cornmeal baked over an open fire), cornmeal mush, or grits made from hominy, whole kernels of dried corn soaked in lye to remove the hard outer layer. The lime in the lye was important, even though the settlers didn’t know it at the time. It makes corn’s niacin content more nutritionally available, reducing the chance of pellagra, a vitamin-deficiency disease.

Pork was the other mainstay of the settlers’ diets. Fried, boiled, salted, smoked, roasted, or stewed, pork found its way into nearly every meal. Some kind of “sallet” or salad was also served like mustard greens or pokeweed. Sometimes eaten fresh, but more often boiled for a long time with a piece of pork rind or bacon for flavor, creating a delicious “pot likker” in which to crumble cornbread. Beverages included sassafras root or spicewood tea, coffee, apple cider, and milk. Most of the family’s foods were skillfully cooked in iron skillets and kettles over an open fire.

Some Early Settlers

From left:

James and Elizabeth Fancher, 1790–1866; 1800–1891. Came to Osage Valley (Carroll County) in 1838 from Tennessee. Farmer; raised 14 children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-18-14 and S-84-211-159)

Fanny Hill, 1833–1918. Brought to Cane Hill (Washington County) as an enslaved person in 1855 from Alabama. Children’s nursemaid, seamstress, nurse, and land owner. Mildred Carnahan Collection (S-98-2-506)

Peter Mankins Sr.,1776–1887. Came to the Sulphur City area (Washington County) in 1832 from Kentucky. Farmer; raised 11 children and 3 stepchildren. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1784)

Bradley Bunch, 1818–1894. Came to Osage Township (Carroll County) about 1838 from Tennessee. Justice of the peace and state senator; raised 12 children. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-6-36)

Andrew Buchanan,1792–1857. Came to Prairie Grove (Washington County) in 1829 from Kentucky. Preacher and farmer; helped establish Cane Hill College; raised 2 stepchildren. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1105)

Preserving and Preparing Food

Abandoned cellar with “stone jars,” probably Cane Hill (Washington County), mid 1900s. Mildred Carnahan Collection (S-98-2-685)

The food that the settlers grew, gathered, and harvested had to be preserved for the times when fresh food was limited, such as winter. If not enough food was produced, or something went wrong in the preservation process, the family would be in dire straits.

Drying. Apples were peeled, quartered, and spread on scaffolds or on a roof and allowed to dry in the hot sun for several days. Pumpkins were sliced into rings and hung by a pole near the fireplace. “Leather britches” were made by drying green beans threaded onto strings. Drying food outside had its dangers, as rain and dew had to be guarded against. If needed, an outdoor stone kiln was built to dry food more quickly.

Corn was usually dried on the ear and often stored in corn cribs, slatted structures with plenty of air circulation. Frank Nance of Madison County, who came with his parents from Kentucky in 1857, said that “grittins” were made by rubbing a semi-dried ear of corn over the rough side of a homemade grater made from a piece of metal punctured with many holes. When needed, corn or wheat was pounded into a flour-like meal at home or at a nearby grist mill.

Cold Storage. The natural insulating and cooling properties of the earth and water were used to preserve foods. “Stone jars” (ceramic crocks) of preserved meat or apple and persimmon butters were kept in root cellars or placed in a springhouse, a small structure built over a natural spring or small creek. Stone-lined cellars or straw-lined holes in the ground held hardy foods like potatoes, apples, pears, turnips, carrots, and cabbages. Sometimes milk and other perishables were lowered in a container or a coarse-fiber tow sack into a well, spring, or creek.

Salting and Smoking. Pork was the only meat that the early settlers were able to preserve long term. The meat was dry-cured, meaning that it was packed in salt for several weeks. As the salt pulls the water out of the meat, it deprives mold and bacteria of moisture. Not only does salt keep meat from spoiling, it also enhances its appearance and improves its texture and flavor. Saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sometimes found in caves, was added to the curing mixture. It helped the meat keep its pink color and improved flavor.

Smoking the meat for several weeks over a small fire of apple or hickory wood adds flavor. More importantly, the compounds in the smoke inhibit or kill microbial growth. If left un-smoked, the meat’s surface fats could go rancid, spoiling the meat and producing an off flavor.

Fermentation and Pickling. Surplus food was turned into beverages or ingredients for food preparation. Corn and fruits were fermented and distilled to make whiskey and fruit brandies, while fermented apple juice was allowed to turn into hard cider. Vinegar was made by boiling apple peels and cores (sometimes adding molasses) and letting the mixture ferment. The microorganisms that cause fermentation release vitamins, making the end product more nutritious.

Cabbage was kept by slicing it thinly and layering it with salt in a stone jar covered with a cloth and weighted down with a plate. The salt released the water in the cabbage creating a brine. The top portion of the cabbage stayed crisp while the bottom turned to sauerkraut. To make headcheese, a meat jelly, the head and feet of a hog were first brined in a salt and vinegar solution and then boiled before the meat was picked off the bones, tied up in a cloth, and allowed to set up until firm.

Mealtime. What did the settlers make with the food they grew, hunted, gathered, and preserved? Nearly every meal featured corn—cornbread, cornpones (water and cornmeal baked over an open fire), cornmeal mush, or grits made from hominy, whole kernels of dried corn soaked in lye to remove the hard outer layer. The lime in the lye was important, even though the settlers didn’t know it at the time. It makes corn’s niacin content more nutritionally available, reducing the chance of pellagra, a vitamin-deficiency disease.

Pork was the other mainstay of the settlers’ diets. Fried, boiled, salted, smoked, roasted, or stewed, pork found its way into nearly every meal. Some kind of “sallet” or salad was also served like mustard greens or pokeweed. Sometimes eaten fresh, but more often boiled for a long time with a piece of pork rind or bacon for flavor, creating a delicious “pot likker” in which to crumble cornbread. Beverages included sassafras root or spicewood tea, coffee, apple cider, and milk. Most of the family’s foods were skillfully cooked in iron skillets and kettles over an open fire.

Photo Gallery

A cow requires milking twice a day if it isn’t nursing a calf. Settlers who allowed their cows to graze at will in the fields surrounding their homestead had to call them back home for milking. Sometimes they were enticed with corn and other treats or by tethering a calf near the cabin. The better the cow was fed, the better the butter tasted. Cows were fed such things as potato peels, broth, cabbage leaves, pumpkins, kitchen scraps—even dishwater!

Fresh milk was strained and allowed to settle so the rich cream would rise to the surface. The cream was skimmed off and agitated in a stoneware (ceramic) churn by moving a wood dasher (paddle) up and down. Eventually small globules of fat formed together. When that happened, the buttermilk was poured off and the churning continued. After much hard work the butter formed into a lump, leaving behind the whey, the watery part of the milk. Whey and sometimes buttermilk were fed to livestock.

Salt was added to the butter for flavor and preservation. It was mixed together in a wood bowl with a small wood paddle which had been wetted to cool the wood and keep the butter from sticking. When stored properly, butter can keep for a long time.

A cow requires milking twice a day if it isn’t nursing a calf. Settlers who allowed their cows to graze at will in the fields surrounding their homestead had to call them back home for milking. Sometimes they were enticed with corn and other treats or by tethering a calf near the cabin. The better the cow was fed, the better the butter tasted. Cows were fed such things as potato peels, broth, cabbage leaves, pumpkins, kitchen scraps—even dishwater!

Fresh milk was strained and allowed to settle so the rich cream would rise to the surface. The cream was skimmed off and agitated in a stoneware (ceramic) churn by moving a wood dasher (paddle) up and down. Eventually small globules of fat formed together. When that happened, the buttermilk was poured off and the churning continued. After much hard work the butter formed into a lump, leaving behind the whey, the watery part of the milk. Whey and sometimes buttermilk were fed to livestock.

Salt was added to the butter for flavor and preservation. It was mixed together in a wood bowl with a small wood paddle which had been wetted to cool the wood and keep the butter from sticking. When stored properly, butter can keep for a long time.

Bohannon family members and friends pause from harvesting wheat with their grain cradles, Bohannon Mountain (Madison County), circa 1900. Julia Outland Collection (S-83-269-11A)

Corn was the most commonly grown grain, but folks also had small patches of wheat, oats, millet, and rye. Wheat thrived especially in the soil and climate of what would become Carroll and Boone Counties.

Early settlers harvested wheat by hand, first with curved knives called sickles, later with grain cradles—huge rake-like devices with a long blade. A skilled worker could harvest two acres of wheat a day with this tool. The advantage of a grain cradle was that it left the wheat heads aligned, making the stalks easier to gather and bind. The grain was dried in the fields in loose windrows (lines) or in shocks, bundles of stalks set on end.

Wheat berries were removed in several ways. The stalks could be beaten against a rod, flailed with a whip, or placed on a “threshing floor,” soil made smooth and hard from repeated tamping with water. Horses were walked around and around to break off the grain. The stalks were removed, the wheat swept up, and the dirt and chaff (plant debris) winnowed (blown) away.

Wheat and corn were often ground at home. One type of homemade mill involved tying a heavy hammer-like maul to one end of a pole which was balanced on a forked limb pushed into the ground. When the free end of the pole was moved up and down, the maul fell into a hollowed-out tree stump full of dried grain. The grain could also be taken to a grist mill, with the miller taking a portion of the grain in payment for his work.

Bohannon family members and friends pause from harvesting wheat with their grain cradles, Bohannon Mountain (Madison County), circa 1900. Julia Outland Collection (S-83-269-11A)

Corn was the most commonly grown grain, but folks also had small patches of wheat, oats, millet, and rye. Wheat thrived especially in the soil and climate of what would become Carroll and Boone Counties.

Early settlers harvested wheat by hand, first with curved knives called sickles, later with grain cradles—huge rake-like devices with a long blade. A skilled worker could harvest two acres of wheat a day with this tool. The advantage of a grain cradle was that it left the wheat heads aligned, making the stalks easier to gather and bind. The grain was dried in the fields in loose windrows (lines) or in shocks, bundles of stalks set on end.

Wheat berries were removed in several ways. The stalks could be beaten against a rod, flailed with a whip, or placed on a “threshing floor,” soil made smooth and hard from repeated tamping with water. Horses were walked around and around to break off the grain. The stalks were removed, the wheat swept up, and the dirt and chaff (plant debris) winnowed (blown) away.

Wheat and corn were often ground at home. One type of homemade mill involved tying a heavy hammer-like maul to one end of a pole which was balanced on a forked limb pushed into the ground. When the free end of the pole was moved up and down, the maul fell into a hollowed-out tree stump full of dried grain. The grain could also be taken to a grist mill, with the miller taking a portion of the grain in payment for his work.

Man with slaughtered hog, Pettigrew area (Madison County), 1920s–1930s. Wayne Martin Collection (S-94-55-54)

Hog butchering happened in the fall and required extra hands to get the work done. Meat was often shared with neighbors who then shared meat when it came time to butcher their livestock. After the hog’s throat was cut it was trussed up by its back legs to let the blood drain out. Its flesh was scalded with hot water and the hair scraped off. The internal organs were removed and the hog was left to cool overnight.

“Everything but the squeal” was used. The chops, backbone, ribs, tenderloin, lungs, and liver were eaten fresh. Headcheese (a meat jelly) was made from the head and feet. Brains were scrambled in eggs. Sausage was made by pounding meat scraps and fat with seasoning and stuffing the mixture into lengths of clean intestine. The fat was cooked slowly over a low fire to render out the lard. The lard was strained, leaving behind the cracklings (fried pork skin) which could be stirred into cornbread batter or used to make soap.

Some meat was cooked and placed in covered stoneware (ceramic) jars and preserved between layers of lard. Hams, shoulders, and side meat were covered in salt for three to six weeks, then hung in the smokehouse and smoked with hickory or sassafras chips for several weeks. Properly done, the salting, drying, and smoking process preserved the meat through the following summer. So what if a bit of mold had to be scraped off the outer layer of fat?

Man with slaughtered hog, Pettigrew area (Madison County), 1920s–1930s. Wayne Martin Collection (S-94-55-54)

Hog butchering happened in the fall and required extra hands to get the work done. Meat was often shared with neighbors who then shared meat when it came time to butcher their livestock. After the hog’s throat was cut it was trussed up by its back legs to let the blood drain out. Its flesh was scalded with hot water and the hair scraped off. The internal organs were removed and the hog was left to cool overnight.

“Everything but the squeal” was used. The chops, backbone, ribs, tenderloin, lungs, and liver were eaten fresh. Headcheese (a meat jelly) was made from the head and feet. Brains were scrambled in eggs. Sausage was made by pounding meat scraps and fat with seasoning and stuffing the mixture into lengths of clean intestine. The fat was cooked slowly over a low fire to render out the lard. The lard was strained, leaving behind the cracklings (fried pork skin) which could be stirred into cornbread batter or used to make soap.

Some meat was cooked and placed in covered stoneware (ceramic) jars and preserved between layers of lard. Hams, shoulders, and side meat were covered in salt for three to six weeks, then hung in the smokehouse and smoked with hickory or sassafras chips for several weeks. Properly done, the salting, drying, and smoking process preserved the meat through the following summer. So what if a bit of mold had to be scraped off the outer layer of fat?

One way to preserve food for long periods of time is to keep it cool. Settlers used the earth’s natural insulating properties by storing hardy foods like potatoes or cabbage in straw-lined holes in the ground. Containers of food were suspended in wells or stored in springhouses, small sheds built over a spring or small creek. Caves and bluffs with overhanging ledges were cool spots, especially if a spring flowed out of them.

Winter often served as nature’s refrigerator. Food was buried in snow. Some folks cut blocks of ice from a frozen creek or pond and buried it below ground, surrounded by straw or sawdust, to keep (hopefully) through the summer months. Only a few families had the resources and labor to build icehouses. One surviving icehouse exists at the Peel House in Bentonville (Benton County). Built in 1875, the brick walls are over 11 inches thick. A three-inch hollow between the layers of brick was filled with sawdust

One way to preserve food for long periods of time is to keep it cool. Settlers used the earth’s natural insulating properties by storing hardy foods like potatoes or cabbage in straw-lined holes in the ground. Containers of food were suspended in wells or stored in springhouses, small sheds built over a spring or small creek. Caves and bluffs with overhanging ledges were cool spots, especially if a spring flowed out of them.

Winter often served as nature’s refrigerator. Food was buried in snow. Some folks cut blocks of ice from a frozen creek or pond and buried it below ground, surrounded by straw or sawdust, to keep (hopefully) through the summer months. Only a few families had the resources and labor to build icehouses. One surviving icehouse exists at the Peel House in Bentonville (Benton County). Built in 1875, the brick walls are over 11 inches thick. A three-inch hollow between the layers of brick was filled with sawdust

Young squirrel hunter, Kingston (Madison County), early 1920s. Flossie Smith Collection (S-98-88-500)

When the settlers arrived, their first meals were often made up of what they could find in the fields and forests surrounding their new homestead. It took time to plant crops and raise livestock. Later, wild game supplemented homegrown food and offered a varied diet.

Jim Auslam, who was born in Huntsville (Madison County) in 1866, remembered that as a youngster he and his neighbors took their guns and dogs out to hunt for meat. There were plenty of wild hogs where he lived. Hunters had to be careful, because the hogs were mean following a lean, hungry winter. “They would fight anything that would try to bother them, and they usually won. I have seen them cut a dog’s throat at one swipe, just like it was cut with a knife.”

A hunter had to take careful aim. The loud blast from a misfired shot caused the game to flee long before he had time to carefully reload his firearm. Plus, gunpowder, percussion caps, and lead had to be purchased, meaning that every shot had to count. Bullets were made at home by pouring molten lead into metal molds. Animal traps were made from such things as hollow logs, sapling branches, and rawhide cord.

Hunters employed careful observation to follow animal tracks and note deer trails, rabbit holes, bear dens, and turkey roosts. Dogs were used to track wildlife and drive them into tight spots where they could be killed. At night, a burning pine knot might be used to shine light into a deer’s eyes, momentarily bewildering it.

Most folks kept their rifle or muzzleloader handy, even while working the fields. One never knew when the opportunity to shoot game would come up. And firearms offered protection against strangers and predators. Hunters took aim on the wolves and wildcats that preyed on their livestock.

Young squirrel hunter, Kingston (Madison County), early 1920s. Flossie Smith Collection (S-98-88-500)

When the settlers arrived, their first meals were often made up of what they could find in the fields and forests surrounding their new homestead. It took time to plant crops and raise livestock. Later, wild game supplemented homegrown food and offered a varied diet.

Jim Auslam, who was born in Huntsville (Madison County) in 1866, remembered that as a youngster he and his neighbors took their guns and dogs out to hunt for meat. There were plenty of wild hogs where he lived. Hunters had to be careful, because the hogs were mean following a lean, hungry winter. “They would fight anything that would try to bother them, and they usually won. I have seen them cut a dog’s throat at one swipe, just like it was cut with a knife.”

A hunter had to take careful aim. The loud blast from a misfired shot caused the game to flee long before he had time to carefully reload his firearm. Plus, gunpowder, percussion caps, and lead had to be purchased, meaning that every shot had to count. Bullets were made at home by pouring molten lead into metal molds. Animal traps were made from such things as hollow logs, sapling branches, and rawhide cord.

Hunters employed careful observation to follow animal tracks and note deer trails, rabbit holes, bear dens, and turkey roosts. Dogs were used to track wildlife and drive them into tight spots where they could be killed. At night, a burning pine knot might be used to shine light into a deer’s eyes, momentarily bewildering it.

Most folks kept their rifle or muzzleloader handy, even while working the fields. One never knew when the opportunity to shoot game would come up. And firearms offered protection against strangers and predators. Hunters took aim on the wolves and wildcats that preyed on their livestock.

Joe Rich plowing a field with the help of his mule, “John the Baptist,” Newton County, mid 1930s. Opal or Ernest Nicholson, photographer. Katie McCoy Collection (S-95-181-76)

Before a crop could be planted, the land had to be readied. Prairies existed in Northwest Arkansas, especially in the western half, and it didn’t take much to till the ground. In forested areas, trees were chopped down and stumps pulled from the ground or left in place and farmed around. Brush and shrubs were cleared with a grub (digging) hoe. Oxen, mules, and sometimes horses were used to pull homemade plows to break the ground. When a rock was hit, the plow often jerked out of the farmer’s control, hitting him in the leg or chest.

Some fields were “deadened” in preparation for future plowing or as a quick way to begin planting without the labor of chopping down and removing trees. First, a small strip of bark was removed around the trunk. Eventually the tree died, decayed, and fell over, often after a storm. Stout, pointed sticks, about five feet in length, were used to roll the logs from the field. “Log rollings” were festive occasions when neighbors helped clear fields and shared good food and merriment.

Making a field in the fertile bottomlands was relatively easy compared to farming a terrace-like mountain “bench” made up of rocks and poor soil. William Harrison Collins, who was born in Newton County in the late 1880s, recalled his father Searl’s farm. “Oh that land on the Buffalo was rich! My father owned what he called the bench field on the west side of the creek; the sun’d shine there ever’ mornin,’ and that corn’d sure pop up!” Some farmers practiced crop rotation but many didn’t. When a field’s nutrients gave out after a few years, the land was abandoned and a new area cleared and plowed.

Joe Rich plowing a field with the help of his mule, “John the Baptist,” Newton County, mid 1930s. Opal or Ernest Nicholson, photographer. Katie McCoy Collection (S-95-181-76)

Before a crop could be planted, the land had to be readied. Prairies existed in Northwest Arkansas, especially in the western half, and it didn’t take much to till the ground. In forested areas, trees were chopped down and stumps pulled from the ground or left in place and farmed around. Brush and shrubs were cleared with a grub (digging) hoe. Oxen, mules, and sometimes horses were used to pull homemade plows to break the ground. When a rock was hit, the plow often jerked out of the farmer’s control, hitting him in the leg or chest.

Some fields were “deadened” in preparation for future plowing or as a quick way to begin planting without the labor of chopping down and removing trees. First, a small strip of bark was removed around the trunk. Eventually the tree died, decayed, and fell over, often after a storm. Stout, pointed sticks, about five feet in length, were used to roll the logs from the field. “Log rollings” were festive occasions when neighbors helped clear fields and shared good food and merriment.

Making a field in the fertile bottomlands was relatively easy compared to farming a terrace-like mountain “bench” made up of rocks and poor soil. William Harrison Collins, who was born in Newton County in the late 1880s, recalled his father Searl’s farm. “Oh that land on the Buffalo was rich! My father owned what he called the bench field on the west side of the creek; the sun’d shine there ever’ mornin,’ and that corn’d sure pop up!” Some farmers practiced crop rotation but many didn’t. When a field’s nutrients gave out after a few years, the land was abandoned and a new area cleared and plowed.

John Noel Pool (left) and George Stewart in a corn field, Thompson Switch area (near Elkins, Washington County), circa 1900. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-90-48-31)

Corn was easy to plant and grow and was often the settlers’ first crop—along with pork, it was the mainstay of their diet. Growing crops required vigilance, not only from wandering livestock but from wildlife. Turkeys might get into the pea patch or squirrels in the corn.

Come harvest time the green leaves were pulled off and dried for animal fodder. The top of the stalk was lopped off. As the stalk dried, the ears were snapped off. “Roasting ears” (fresh corn) were boiled and eaten right away. Some folks cut off the corn kernels to dry. Others dried the corn with their outer shucks on the ears and stored them in the corn crib, a well-ventilated structure. The best corn was saved for human consumption; the rest was fed to the livestock.

Sometimes a shucking party was organized to process a large amount of corn. Games, music, and dancing made the labor-intensive, time-consuming chore more appealing. John Ed Watkins was born in the upper Crooked Creek Valley (Boone County) in 1854. He remembered a time when a jug of Parker’s brandy was hidden in a pile of corn to further motivate the huskers.

Corn shucks were used when making brooms, stuffing mattresses, and fashioning simple work hats or collars for plow animals. The cobs were burned as fuel or used in place of toilet paper.

John Noel Pool (left) and George Stewart in a corn field, Thompson Switch area (near Elkins, Washington County), circa 1900. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-90-48-31)

Corn was easy to plant and grow and was often the settlers’ first crop—along with pork, it was the mainstay of their diet. Growing crops required vigilance, not only from wandering livestock but from wildlife. Turkeys might get into the pea patch or squirrels in the corn.

Come harvest time the green leaves were pulled off and dried for animal fodder. The top of the stalk was lopped off. As the stalk dried, the ears were snapped off. “Roasting ears” (fresh corn) were boiled and eaten right away. Some folks cut off the corn kernels to dry. Others dried the corn with their outer shucks on the ears and stored them in the corn crib, a well-ventilated structure. The best corn was saved for human consumption; the rest was fed to the livestock.

Sometimes a shucking party was organized to process a large amount of corn. Games, music, and dancing made the labor-intensive, time-consuming chore more appealing. John Ed Watkins was born in the upper Crooked Creek Valley (Boone County) in 1854. He remembered a time when a jug of Parker’s brandy was hidden in a pile of corn to further motivate the huskers.

Corn shucks were used when making brooms, stuffing mattresses, and fashioning simple work hats or collars for plow animals. The cobs were burned as fuel or used in place of toilet paper.

Henry Tarleton Lane feeding sorghum stalks into a mill, Kingston area (Madison County), circa 1953. Cleburn Smith Collection (S-98-1-82)

Northwest Arkansas’ first settlers didn’t grow sorghum but relied on honey and maple syrup for their sweeteners. There is some speculation that sorghum didn’t come to this area until the 1860s. Once it did, it was heartily embraced. Not only was sorghum molasses the main sweetener for many, it is rich in iron and calcium.

In the early 1870s Ora Obenchain and her sister Zelah helped with the sorghum harvest in Viney Grove (Washington County). The girls’ job was to pull the leaves from the stalks and tie them into bundles for animal fodder. Then the stalks could be harvested to make “lasses” (sorghum molasses).

A wood sorghum mill was often shared by neighbors. When it was in operation, its creaking could be heard for miles. It was turned by a mule or horse walking in circles while harnessed to a long log pole called a sweep. The stalks were cut and fed into the mill. The liquid that came from the crushed stalks was placed in a large iron kettle and boiled over a fire until it was dark and syrupy. After it cooled, the finished molasses was strained by pouring it through a coarse cloth. In later years, a long, shallow metal pan was used to more effectively cook down the sorghum juice.

Henry Tarleton Lane feeding sorghum stalks into a mill, Kingston area (Madison County), circa 1953. Cleburn Smith Collection (S-98-1-82)

Northwest Arkansas’ first settlers didn’t grow sorghum but relied on honey and maple syrup for their sweeteners. There is some speculation that sorghum didn’t come to this area until the 1860s. Once it did, it was heartily embraced. Not only was sorghum molasses the main sweetener for many, it is rich in iron and calcium.

In the early 1870s Ora Obenchain and her sister Zelah helped with the sorghum harvest in Viney Grove (Washington County). The girls’ job was to pull the leaves from the stalks and tie them into bundles for animal fodder. Then the stalks could be harvested to make “lasses” (sorghum molasses).

A wood sorghum mill was often shared by neighbors. When it was in operation, its creaking could be heard for miles. It was turned by a mule or horse walking in circles while harnessed to a long log pole called a sweep. The stalks were cut and fed into the mill. The liquid that came from the crushed stalks was placed in a large iron kettle and boiled over a fire until it was dark and syrupy. After it cooled, the finished molasses was strained by pouring it through a coarse cloth. In later years, a long, shallow metal pan was used to more effectively cook down the sorghum juice.

No matter how hot it might be outside, a fire was necessary year round to cook the family’s meals. A kettle hanging over the fire allowed the settlers to boil coffee, make stews, and heat water. Cornbread, cobbler, and biscuits were made in a footed Dutch oven. To create uniform heat, hot coals were placed underneath the oven and on top of its deeply rimmed lid. Other pots and pans were balanced carefully on the burning wood.

A hearty breakfast was necessary given the long work day ahead. Since every hour of light was needed to get the chores done, the womenfolk got up early to make the meal and have it on the table before daybreak. Margaret Woods’ ancestors came to Benton County in 1838. Their typical breakfast included:

“. . . fried meat [wild turkey, venison, or prairie chicken], . . . flanked by a large bowl of cream gravy . . . sausage or fried pork, and in summer and fall it likely would be chicken or ham and brown gravy; a dish of wild honey, always a dish of golden butter and plates of hot biscuit coming fresh from the old dutch oven every few minutes, with wild fruit in season and dried fruits in the winter, and at our house there was always a pitcher of sorghum. . . . [and] a huge coffee pot and large pitcher of milk.”

Dinner (what we would call lunch) was the main meal of the day. It might feature boiled ham, cracklin’ cornbread made with fried pigskin, sweet potatoes roasted in ashes, fried vegetables, poke sallet, and a fruit cobbler topped with a mixture of molasses and milk. In the evening folks ate the day’s leftovers or cornmeal mush and milk for supper. Wheat-flour biscuits were made on Sundays and special occasions. Frank Nance, who came to Madison County from Kentucky in 1857, recalled that corncobs were burned for soda ash, a leavener used when making quick (unyeasted) bread.

Fireplaces often caught on fire, especially those with chimneys made of sticks and clay. The logs were doused with water and water was thrown up the chimney and onto its exterior. If necessary, a stout stick was used to push the burning chimney away from the house.

No matter how hot it might be outside, a fire was necessary year round to cook the family’s meals. A kettle hanging over the fire allowed the settlers to boil coffee, make stews, and heat water. Cornbread, cobbler, and biscuits were made in a footed Dutch oven. To create uniform heat, hot coals were placed underneath the oven and on top of its deeply rimmed lid. Other pots and pans were balanced carefully on the burning wood.

A hearty breakfast was necessary given the long work day ahead. Since every hour of light was needed to get the chores done, the womenfolk got up early to make the meal and have it on the table before daybreak. Margaret Woods’ ancestors came to Benton County in 1838. Their typical breakfast included:

“. . . fried meat [wild turkey, venison, or prairie chicken], . . . flanked by a large bowl of cream gravy . . . sausage or fried pork, and in summer and fall it likely would be chicken or ham and brown gravy; a dish of wild honey, always a dish of golden butter and plates of hot biscuit coming fresh from the old dutch oven every few minutes, with wild fruit in season and dried fruits in the winter, and at our house there was always a pitcher of sorghum. . . . [and] a huge coffee pot and large pitcher of milk.”

Dinner (what we would call lunch) was the main meal of the day. It might feature boiled ham, cracklin’ cornbread made with fried pigskin, sweet potatoes roasted in ashes, fried vegetables, poke sallet, and a fruit cobbler topped with a mixture of molasses and milk. In the evening folks ate the day’s leftovers or cornmeal mush and milk for supper. Wheat-flour biscuits were made on Sundays and special occasions. Frank Nance, who came to Madison County from Kentucky in 1857, recalled that corncobs were burned for soda ash, a leavener used when making quick (unyeasted) bread.

Fireplaces often caught on fire, especially those with chimneys made of sticks and clay. The logs were doused with water and water was thrown up the chimney and onto its exterior. If necessary, a stout stick was used to push the burning chimney away from the house.

Sarah Harriet Ford Cooper Blaylock in her herb garden, Posey Mountain (near Garfield, Benton County), early 1900s. Blaylock was a midwife and, like her father, an herb doctor. Benton County Historical Society/Dorothy Ellis Ross Collection (S-92-49-68)

A few medical doctors practiced on the frontier, but they had to ride many miles to tend their patients. Settlers often used plants and roots grown in a garden or gathered from the wild to treat their own ailments and those of their livestock.

Some folks were noted for their home remedies. Herb doctors like Sarah Blaylock, who came to the Garfield area from Tennessee in the 1850s, often treated her neighbors, sometimes under dangerous circumstances. One story tells of Sarah racing through the countryside one night, trying to stay balanced on her horse’s sidesaddle. She was fleeing a panther as it chased after her, leaping limb to limb through the trees.

Scores of plants were used to treat ailments. Sassafras tea was drunk in the springtime to thin the blood. Dried mullein leaves were smoked in a pipe to cure a cough. Horehound was turned into a cough syrup. Pawpaw seeds and Jimson weed were pulverized and fed to dogs and horses recovering from distemper. The juice from the Jimson weed stalk was used for sore eyes. Sprained joints required a poultice (covering) of boiled wheat bran and peach-tree leaves or red-oak bark. During the Civil War, some soldiers chewed on slippery elm bark to keep down their thirst for water.

Sarah Harriet Ford Cooper Blaylock in her herb garden, Posey Mountain (near Garfield, Benton County), early 1900s. Blaylock was a midwife and, like her father, an herb doctor. Benton County Historical Society/Dorothy Ellis Ross Collection (S-92-49-68)

A few medical doctors practiced on the frontier, but they had to ride many miles to tend their patients. Settlers often used plants and roots grown in a garden or gathered from the wild to treat their own ailments and those of their livestock.

Some folks were noted for their home remedies. Herb doctors like Sarah Blaylock, who came to the Garfield area from Tennessee in the 1850s, often treated her neighbors, sometimes under dangerous circumstances. One story tells of Sarah racing through the countryside one night, trying to stay balanced on her horse’s sidesaddle. She was fleeing a panther as it chased after her, leaping limb to limb through the trees.

Scores of plants were used to treat ailments. Sassafras tea was drunk in the springtime to thin the blood. Dried mullein leaves were smoked in a pipe to cure a cough. Horehound was turned into a cough syrup. Pawpaw seeds and Jimson weed were pulverized and fed to dogs and horses recovering from distemper. The juice from the Jimson weed stalk was used for sore eyes. Sprained joints required a poultice (covering) of boiled wheat bran and peach-tree leaves or red-oak bark. During the Civil War, some soldiers chewed on slippery elm bark to keep down their thirst for water.

Young boys feeding dried corn to chickens, possibly Boston area (Madison County), 1900s–1910s. Otto Bennett Collection (S-99-66-789)

While they were alive, chickens produced eggs. After they were killed their meat was cooked and eaten and their bones rendered into stock. Other poultry like geese and ducks were kept primarily for their feathers. Several times a year the down and the soft feathers of the neck and breast were plucked to make pillows and mattress ticks. Plucking day often resembled a mini-snowfall.

Chickens roamed the farmyard. Sometimes they were penned up at night, but often they were allowed to roost in the lower limbs of shade trees to keep away from predators. Protecting livestock from wolves and wildcats was critical. James F. “Major” Keck was born at Witter (Madison County) in 1864. When he was a boy, his family “would pen our young calves up in the chimney corner, and lots of times we would have to get up during the night and beat the wolves off of them.”

Children worked as hard on the farm as did the adults. They fed animals, harvested food, cooked meals, hauled water, churned butter, plowed fields, spun thread, and chopped wood. Not only did they provide much-needed help, they learned the skills they would likely need as adults.

Young boys feeding dried corn to chickens, possibly Boston area (Madison County), 1900s–1910s. Otto Bennett Collection (S-99-66-789)

While they were alive, chickens produced eggs. After they were killed their meat was cooked and eaten and their bones rendered into stock. Other poultry like geese and ducks were kept primarily for their feathers. Several times a year the down and the soft feathers of the neck and breast were plucked to make pillows and mattress ticks. Plucking day often resembled a mini-snowfall.

Chickens roamed the farmyard. Sometimes they were penned up at night, but often they were allowed to roost in the lower limbs of shade trees to keep away from predators. Protecting livestock from wolves and wildcats was critical. James F. “Major” Keck was born at Witter (Madison County) in 1864. When he was a boy, his family “would pen our young calves up in the chimney corner, and lots of times we would have to get up during the night and beat the wolves off of them.”

Children worked as hard on the farm as did the adults. They fed animals, harvested food, cooked meals, hauled water, churned butter, plowed fields, spun thread, and chopped wood. Not only did they provide much-needed help, they learned the skills they would likely need as adults.

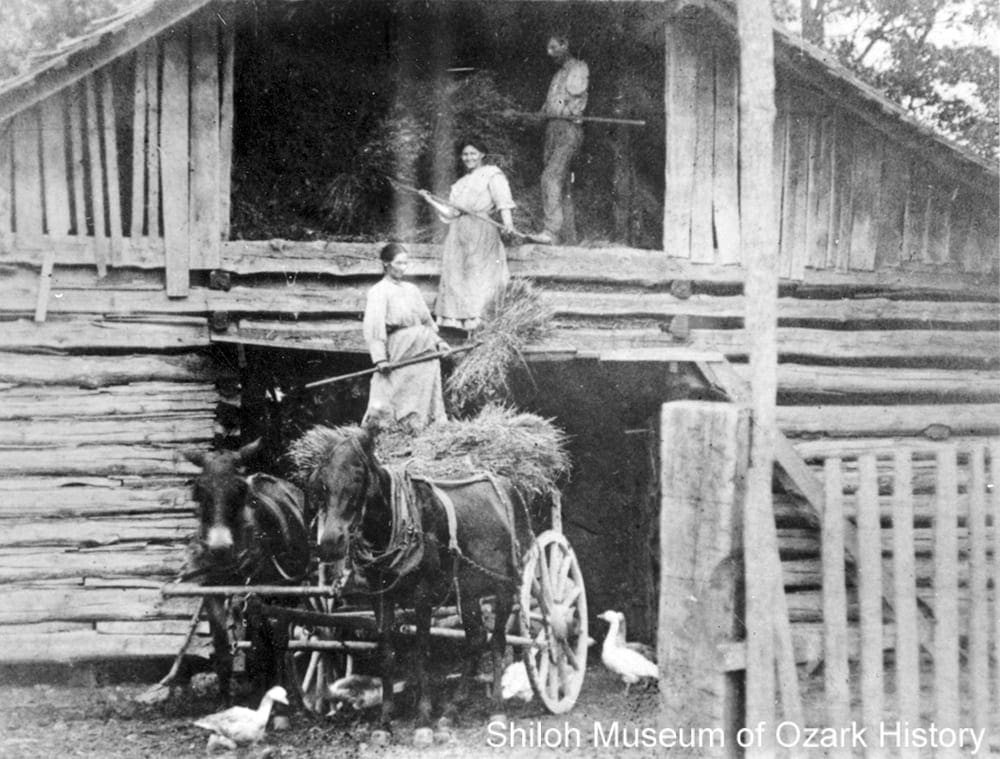

Tellitha Patton Light (bottom), Robert Light, and their daughter Annie Light storing hay in the barn loft, Pleasant Hill township (Newton County), early 1900s. Cora Humble Collection (S-88-135-10)

Livestock were fed all sorts of things. Salt was placed in troughs made from hollowed-out logs to keep cattle healthy. Horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, and mules roamed the fields and forests during the day to graze. In the springtime the nearby woods could be set on fire, killing the undergrowth and allowing tender grasses to emerge. During the winter, cattle, horses, and mules ate fodder, the dried leaves and stalks from plants like corn and sorghum. Hay was a type of fodder, made from dry grasses.

Folks knew to “make hay while the sun shines.” When a dry period was expected, grass was cut and laid in loose windrows (lines) in the field. During the day it dried and at night it was gathered together to protect it from dew. Hay took several sunny days to dry. Once it was ready, the hay was stacked outdoors in large mounds or placed in a barn with the other animal fodder. If it wasn’t fully dried, heat from the decaying plant material caused the pile to catch on fire.

Tellitha Patton Light (bottom), Robert Light, and their daughter Annie Light storing hay in the barn loft, Pleasant Hill township (Newton County), early 1900s. Cora Humble Collection (S-88-135-10)

Livestock were fed all sorts of things. Salt was placed in troughs made from hollowed-out logs to keep cattle healthy. Horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, and mules roamed the fields and forests during the day to graze. In the springtime the nearby woods could be set on fire, killing the undergrowth and allowing tender grasses to emerge. During the winter, cattle, horses, and mules ate fodder, the dried leaves and stalks from plants like corn and sorghum. Hay was a type of fodder, made from dry grasses.