Single Pens, Saddlebags, and Dog Trots

Online Exhibit

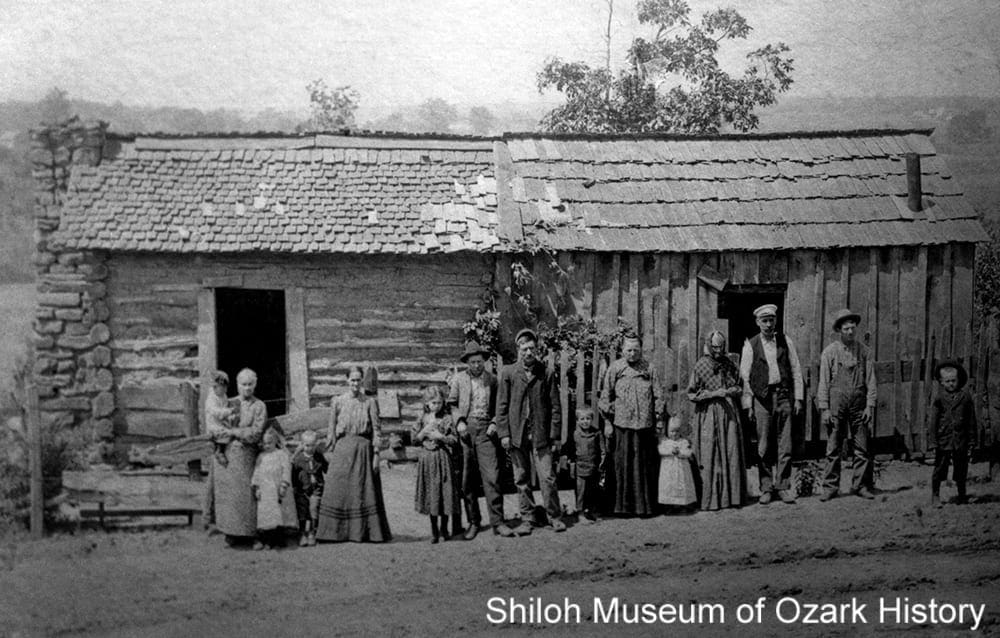

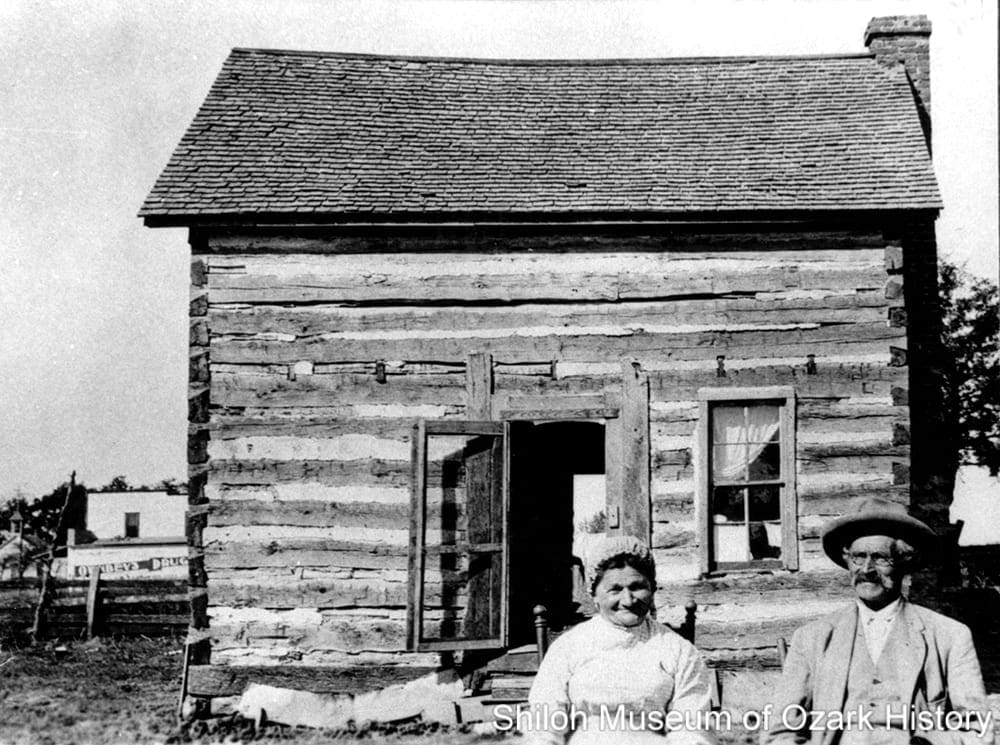

The Wesley Graham family by their single pen log cabin, Monitor community near Springdale, circa 1893. From left, Calvin, Hulda, Ervin, Wesley, Callie, Dollie, Nancy, Frankie, and Doss Graham. Willard Graham Collection (S-92-35-2)

Imagine coming to a new land and having to build a house, plant crops, and make tools, furnishings, and clothes in order to survive. For the folks who began settling the Arkansas Ozarks in the 1820s and 1830s, one of the most important skills they brought with them was the ability to build a home from logs.

So why does the thought of a log cabin often conjure up two such different images of early Americans? On the one hand is a type of rough nobility—think hardy pioneers and young Abe Lincoln reading by firelight. On the other hand is the stereotype of the poor, ignorant, backwoods hillbilly.

City dwellers might view homespun clothing, loose hogs, and corn patches as primitive, but in truth the people who lived in log homes were self-sufficient, independent-minded farmers. They used their skills and resourcefulness to raise families and live off the land.

The Log Building Comes West

Building styles evolve over time. They are influenced by many factors including cultural traditions, available building materials and skilled workers, and the need to solve problems unique to a certain terrain or climate.

As early as the 1830s land shortages in the east forced a growing population to move westward toward new frontiers. As settlers gradually migrated across the country, so did their particular architectural styles and building techniques.

Scholars have defined several folk-culture regions in the eastern half of the United States. The cultural traditions found in the Ozarks reflect those of the Upland South (southern Appalachia). In turn, these traditions originally derived from those found in the Middle Atlantic colonies where small, one-room log homes were generally built using German log-construction techniques. Swedish log-construction techniques, which in part used round logs, are found further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

According to census records, between 1830 and 1880 the majority of new settlers in the Arkansas Ozarks came from Tennessee and Missouri. Most were native-born Americans of Anglo-Saxon origin, but some were of African descent, brought here as enslaved workers.

Traditional Ozark Log Buildings

Most early homes were one-room deep and one-story high. That’s because traditional log-construction techniques made it difficult to interlock two or more logs to create a long wall. And unless a second story was part of the original construction, adding a new floor to an already finished house meant removing the roof and starting anew.

The Ozark homebuilder was tradition-bound. Because of a shared idea of what a home should look like, there were few variations in home styles from builder to builder. In general, log homes had a definite “front” along the length of the house, normally facing the road. Homes were often symmetrical, the left half mirroring the right. When additions were needed the simplicity of the architectural style meant that it was easy to add on while maintaining a visual balance.

Many log buildings are called log cabins, but a true cabin is made up of a single square or rectangular unit called a “pen.” The size of the pen depended upon the size of log two men could comfortably handle, usually between 12 and 18 feet in length. A pen was an indivisible unit, both in the way it was constructed and in the mind-set of the builder. To enlarge a home, one had to build another pen or attach a shed, not enlarge the existing pen.

The Wesley Graham family by their single pen log cabin, Monitor community near Springdale, circa 1893. From left, Calvin, Hulda, Ervin, Wesley, Callie, Dollie, Nancy, Frankie, and Doss Graham. Willard Graham Collection (S-92-35-2)

Imagine coming to a new land and having to build a house, plant crops, and make tools, furnishings, and clothes in order to survive. For the folks who began settling the Arkansas Ozarks in the 1820s and 1830s, one of the most important skills they brought with them was the ability to build a home from logs.

So why does the thought of a log cabin often conjure up two such different images of early Americans? On the one hand is a type of rough nobility—think hardy pioneers and young Abe Lincoln reading by firelight. On the other hand is the stereotype of the poor, ignorant, backwoods hillbilly.

City dwellers might view homespun clothing, loose hogs, and corn patches as primitive, but in truth the people who lived in log homes were self-sufficient, independent-minded farmers. They used their skills and resourcefulness to raise families and live off the land.

The Log Building Comes West

Building styles evolve over time. They are influenced by many factors including cultural traditions, available building materials and skilled workers, and the need to solve problems unique to a certain terrain or climate.

As early as the 1830s land shortages in the east forced a growing population to move westward toward new frontiers. As settlers gradually migrated across the country, so did their particular architectural styles and building techniques.

Scholars have defined several folk-culture regions in the eastern half of the United States. The cultural traditions found in the Ozarks reflect those of the Upland South (southern Appalachia). In turn, these traditions originally derived from those found in the Middle Atlantic colonies where small, one-room log homes were generally built using German log-construction techniques. Swedish log-construction techniques, which in part used round logs, are found further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

According to census records, between 1830 and 1880 the majority of new settlers in the Arkansas Ozarks came from Tennessee and Missouri. Most were native-born Americans of Anglo-Saxon origin, but some were of African descent, brought here as enslaved workers.

Traditional Ozark Log Buildings

Most early homes were one-room deep and one-story high. That’s because traditional log-construction techniques made it difficult to interlock two or more logs to create a long wall. And unless a second story was part of the original construction, adding a new floor to an already finished house meant removing the roof and starting anew.

The Ozark homebuilder was tradition-bound. Because of a shared idea of what a home should look like, there were few variations in home styles from builder to builder. In general, log homes had a definite “front” along the length of the house, normally facing the road. Homes were often symmetrical, the left half mirroring the right. When additions were needed the simplicity of the architectural style meant that it was easy to add on while maintaining a visual balance.

Many log buildings are called log cabins, but a true cabin is made up of a single square or rectangular unit called a “pen.” The size of the pen depended upon the size of log two men could comfortably handle, usually between 12 and 18 feet in length. A pen was an indivisible unit, both in the way it was constructed and in the mind-set of the builder. To enlarge a home, one had to build another pen or attach a shed, not enlarge the existing pen.

There are four types of log buildings found in the early Ozarks, the rarest being the saddlebag.

Single Pen—One pen with a front door and an exterior chimney on one end.

Single Pen—One pen with a front door and an exterior chimney on one end.

Double Pen—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the two pens, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Double Pen—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the two pens, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Saddlebag—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the pens, and a central interior chimney.

Saddlebag—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the pens, and a central interior chimney.

Dogtrot—Two pens connected by a covered, central breezeway, with two or more doors on the front of the house and in the breezeway, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Dogtrot—Two pens connected by a covered, central breezeway, with two or more doors on the front of the house and in the breezeway, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Log structures weren’t only used as homes. On the farm, animals and hay were kept in log barns, log smokehouses were used to cure meat, log corn cribs held dried ears of corn, and log springhouses protected natural springs. Neighbors shared skills and resources to build log churches and schools for the community. The first courthouses were often built of logs.

Construction Techniques

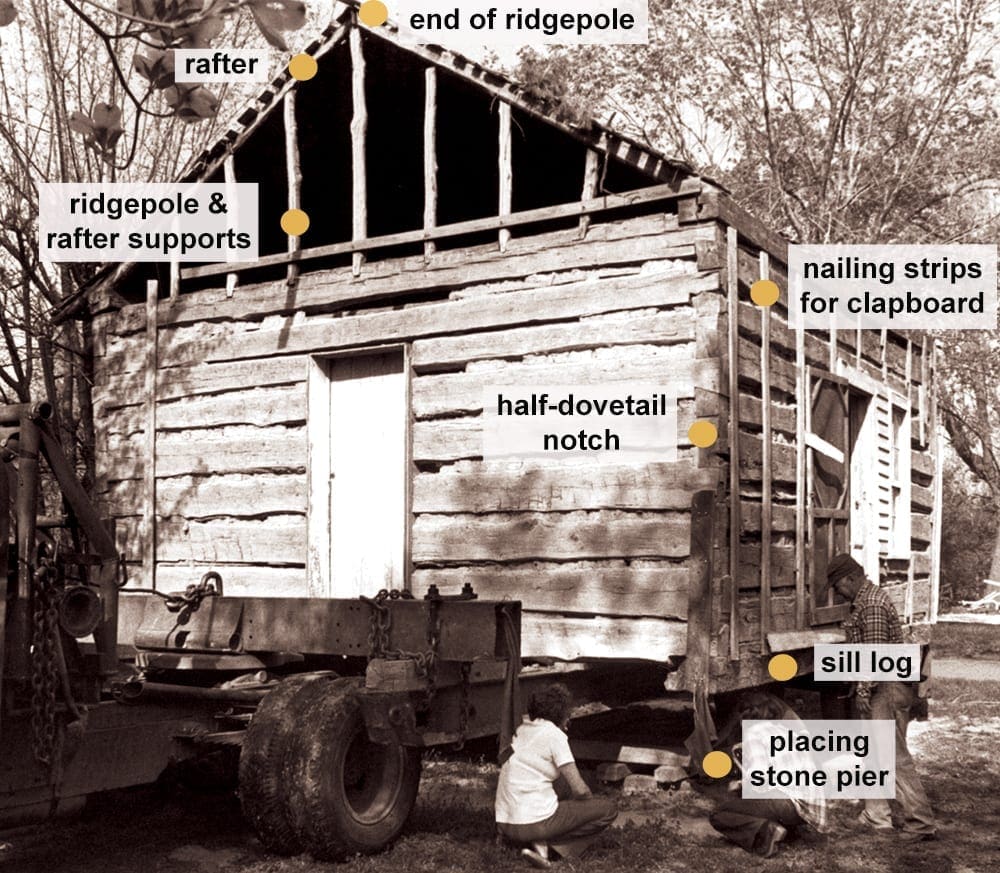

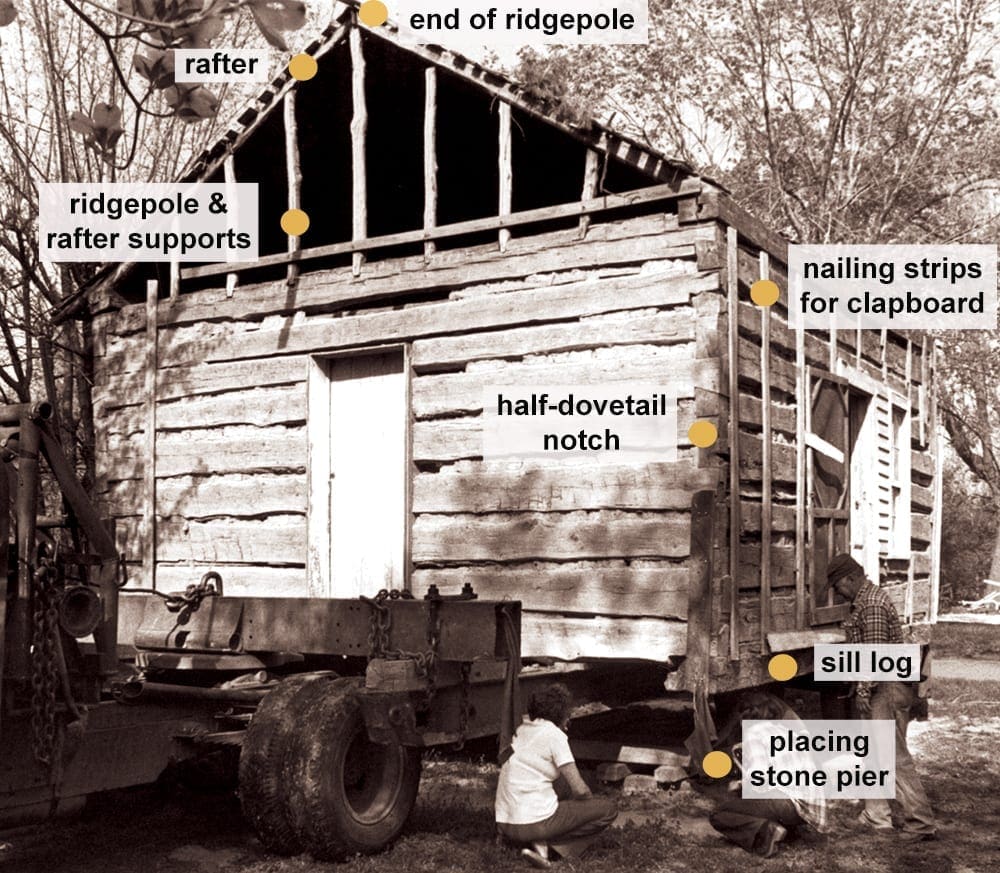

Moving the 1850s Ritter log cabin onto the grounds of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, Springdale, April 22, 1980. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-80-51-4)

It was relatively easy to put up the walls of a log home in a day or two, using just a handful of tools. Most men had a basic knowledge of how to build, but they counted on their neighbors’ skilled assistance. More affluent settlers like John Latta of Washington County relied on his enslaved workers to help build his home.

Home building was a community event. After the homeowner prepared the logs and brought them to the homesite he set the first few courses of timber himself. Then the call went out to neighboring families. While the men and older boys worked, the women prepared food, quilted or sewed, and exchanged news.

Getting to Work

Oak was preferred because it was durable, strong, and readily available. Once a good-sized tree was selected it was chopped down with an ax. Iron and wooden wedges called “gluts” were used to split larger logs. To square up the log, it was laid lengthwise atop other logs to lift it off of the ground. A hewing (cut) line was determined along one side and lightly marked with an ax. The worker stood on top of the log and, taking his chopping ax, deeply scored the side of the log every few inches to the desired depth of the soon-to-be finished side.

Standing on the ground, parallel to the log at one end and slowly moving backwards, the worker carefully swung his heavy broadax, hewing down the line he just scored bit by bit to knock off wood chips and create a flat surface. The log was turned and the next side hewed. Hewing took great strength, control, and stamina.

“Planking” was common in the Ozarks. Not only was it faster to shape only two (opposite) sides of the log for the inner and outer walls, the rough bark left along the top and bottom was thought to better grip the chinking (fill) material. Mules snaked the finished logs from forest to home site.

Sill logs were placed on foot-high stacked stone piers to serve as the base of the walls. Smaller logs used as floor joists were fitted into the sills with mortise joints to hold them into place. While some built their homes close to the ground and used hard-packed soil as their floor, most people secured sawn boards or puncheons, half-round logs, atop their floor joists.

One by one the logs were lifted into place and notched together at the corners, forming the walls. Corner notching was critical. The strength and rigidity of a log wall depends on how well the corners are interlocked. In Northwest Arkansas the half-dovetail notch was the most common notching technique, followed by square notching. The half-dovetail notch was strong and its shape promoted water runoff, thus preventing rot. The projecting ends of the logs were sawed off, squaring up the cabin’s corners.

As the walls grew in height, heavy poles were leaned against them and used as skids. Each log was pushed and pulled up the poles, set on top of the wall, and notched into place. To create the framework for a second floor or loft, or to support the roof system, cross beams were placed across the width of the building. From there the wall could be continued or the roof added.

Finishing the Home

When an opening was needed for a door, window, or fireplace hearth, the height of the opening was determined and the wall built to that level. Two vertical saw cuts were placed in the highest log before another was added. Once the wall was completed, a saw was slipped into the cuts and worked down to the bottom of the desired opening. Wood blocks placed between the gaps in the logs prevented the opening from collapsing. Sawn boards were nailed into either side of the finished opening to create a frame. Some cabins didn’t have windows, as glass was expensive.

The roof system could be made in several ways. One way was to place upright support poles along the middle of the ceiling beams. On top of the center supports sat a long ridgepole running the length of the house. Made of split logs or sawn boards, the rafters formed the diagonal slope of the roof. Placed at intervals, one end of the rafter was secured into the ridgepole while the other end was attached to the wall. Shingles were nailed into strips of wood placed horizontally across the rafters.

Split-wood shingles were made from straight-grained oak. A log was cut into 16-inch lengths and then split into flat blocks. A block was stood on end, a froe blade placed in line with the grain, and a maul was used to hammer the froe down the length of wood, splitting it into shingles. Depending on the size of the house, a thousand or more shingles might be needed.

Chinking made of wood chips or shingles was stuffed diagonally in the gaps between the logs and covered with daubing, usually a lime mortar mixed with clay, mud, or sand. Some builders used only a mortar mix, which wasn’t as weather tight in the long run.

The chimney was often made of stone, either naturally formed or shaped with hammer and chisel to form blocks. Some homes had a stick-and-mud chimney lined with clay. While not ideal, they were relatively easy to put together.

Construction Techniques

Moving the 1850s Ritter log cabin onto the grounds of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, Springdale, April 22, 1980. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (S-80-51-4)

It was relatively easy to put up the walls of a log home in a day or two, using just a handful of tools. Most men had a basic knowledge of how to build, but they counted on their neighbors’ skilled assistance. More affluent settlers like John Latta of Washington County relied on his enslaved workers to help build his home.

Home building was a community event. After the homeowner prepared the logs and brought them to the homesite he set the first few courses of timber himself. Then the call went out to neighboring families. While the men and older boys worked, the women prepared food, quilted or sewed, and exchanged news.

Getting to Work

Oak was preferred because it was durable, strong, and readily available. Once a good-sized tree was selected it was chopped down with an ax. Iron and wooden wedges called “gluts” were used to split larger logs. To square up the log, it was laid lengthwise atop other logs to lift it off of the ground. A hewing (cut) line was determined along one side and lightly marked with an ax. The worker stood on top of the log and, taking his chopping ax, deeply scored the side of the log every few inches to the desired depth of the soon-to-be finished side.

Standing on the ground, parallel to the log at one end and slowly moving backwards, the worker carefully swung his heavy broadax, hewing down the line he just scored bit by bit to knock off wood chips and create a flat surface. The log was turned and the next side hewed. Hewing took great strength, control, and stamina.

“Planking” was common in the Ozarks. Not only was it faster to shape only two (opposite) sides of the log for the inner and outer walls, the rough bark left along the top and bottom was thought to better grip the chinking (fill) material. Mules snaked the finished logs from forest to home site.

Sill logs were placed on foot-high stacked stone piers to serve as the base of the walls. Smaller logs used as floor joists were fitted into the sills with mortise joints to hold them into place. While some built their homes close to the ground and used hard-packed soil as their floor, most people secured sawn boards or puncheons, half-round logs, atop their floor joists.

One by one the logs were lifted into place and notched together at the corners, forming the walls. Corner notching was critical. The strength and rigidity of a log wall depends on how well the corners are interlocked. In Northwest Arkansas the half-dovetail notch was the most common notching technique, followed by square notching. The half-dovetail notch was strong and its shape promoted water runoff, thus preventing rot. The projecting ends of the logs were sawed off, squaring up the cabin’s corners.

As the walls grew in height, heavy poles were leaned against them and used as skids. Each log was pushed and pulled up the poles, set on top of the wall, and notched into place. To create the framework for a second floor or loft, or to support the roof system, cross beams were placed across the width of the building. From there the wall could be continued or the roof added.

Finishing the Home

When an opening was needed for a door, window, or fireplace hearth, the height of the opening was determined and the wall built to that level. Two vertical saw cuts were placed in the highest log before another was added. Once the wall was completed, a saw was slipped into the cuts and worked down to the bottom of the desired opening. Wood blocks placed between the gaps in the logs prevented the opening from collapsing. Sawn boards were nailed into either side of the finished opening to create a frame. Some cabins didn’t have windows, as glass was expensive.

The roof system could be made in several ways. One way was to place upright support poles along the middle of the ceiling beams. On top of the center supports sat a long ridgepole running the length of the house. Made of split logs or sawn boards, the rafters formed the diagonal slope of the roof. Placed at intervals, one end of the rafter was secured into the ridgepole while the other end was attached to the wall. Shingles were nailed into strips of wood placed horizontally across the rafters.

Split-wood shingles were made from straight-grained oak. A log was cut into 16-inch lengths and then split into flat blocks. A block was stood on end, a froe blade placed in line with the grain, and a maul was used to hammer the froe down the length of wood, splitting it into shingles. Depending on the size of the house, a thousand or more shingles might be needed.

Chinking made of wood chips or shingles was stuffed diagonally in the gaps between the logs and covered with daubing, usually a lime mortar mixed with clay, mud, or sand. Some builders used only a mortar mix, which wasn’t as weather tight in the long run.

The chimney was often made of stone, either naturally formed or shaped with hammer and chisel to form blocks. Some homes had a stick-and-mud chimney lined with clay. While not ideal, they were relatively easy to put together.

Icon of the Ozarks

The Fincher family by their single pen log cabin, near Maguiretown (Washington County), mid 1890s. From left: John, Nora, Indiana, Charles, and Kate Fincher. Tom Fincher Collection (S-83-139-13)

Life in a single-pen log cabin was cramped, especially for a large family. Eating, sleeping, and other activities all happened in the same space. Furniture and personal belongings, including clothes, were kept to a minimum. In a house with two pens, one served as a general living area while the other held the kitchen and dining room. Folks might sleep in either room or in a loft, if they had one. During summer, doors and windows were thrown open to catch a cooling breeze. When winter winds blew through the chinking, even a blazing fire might not keep the house warm enough.

Changing Times

Early Ozarkers were recyclers. Rather than build new houses, they added onto their existing homes. Cramped single pen cabins soon became dogtrots or double-pen houses. Lean-to rooms made of sawn boards were tacked on for additional space, further obscuring the footprint of the original pens. For added protection from the elements, wide weatherboards made of planked wood were attached horizontally to the home’s exterior.

As families prospered and earned enough cash to purchase milled lumber, they added siding and fancy trim to their home to give it a modern appearance. By the early 20th century many log homes had been transformed, buried deep within the walls of an enlarged, up-to-date house.

If a family built a new home, the old log building was often used as a farm building or for storage. In 1898 abandoned log cabins were pressed into service as temporary homes for the newest settlers to the Ozarks—the Italian immigrants of Tontitown (Washington County).

End of an Era

Log-home construction lessened by the 1880s, especially in the more populated areas of Northwest Arkansas. The availability of milled lumber, cash income, and modern architectural styles prompted the switch to the frame-style housing of today.

It wasn’t until the 1920s and 1930s that another wave of log-building construction began. As New York’s rustic Adirondack architectural style came into vogue nationwide, it was often used for vacation cottages. During the Great Depression, when several area state parks were constructed under the Works Progress Administration, recreational cabins and other structures were built using a simplified Lincoln Log-type architecture, along the lines of the Adirondack style. Impoverished families, especially in rural areas, were sometimes forced to build log homes for shelter. Compared to those of their ancestors, the structures were inelegant and crudely built. The log-building tradition had been lost.

An Icon of the Ozarks

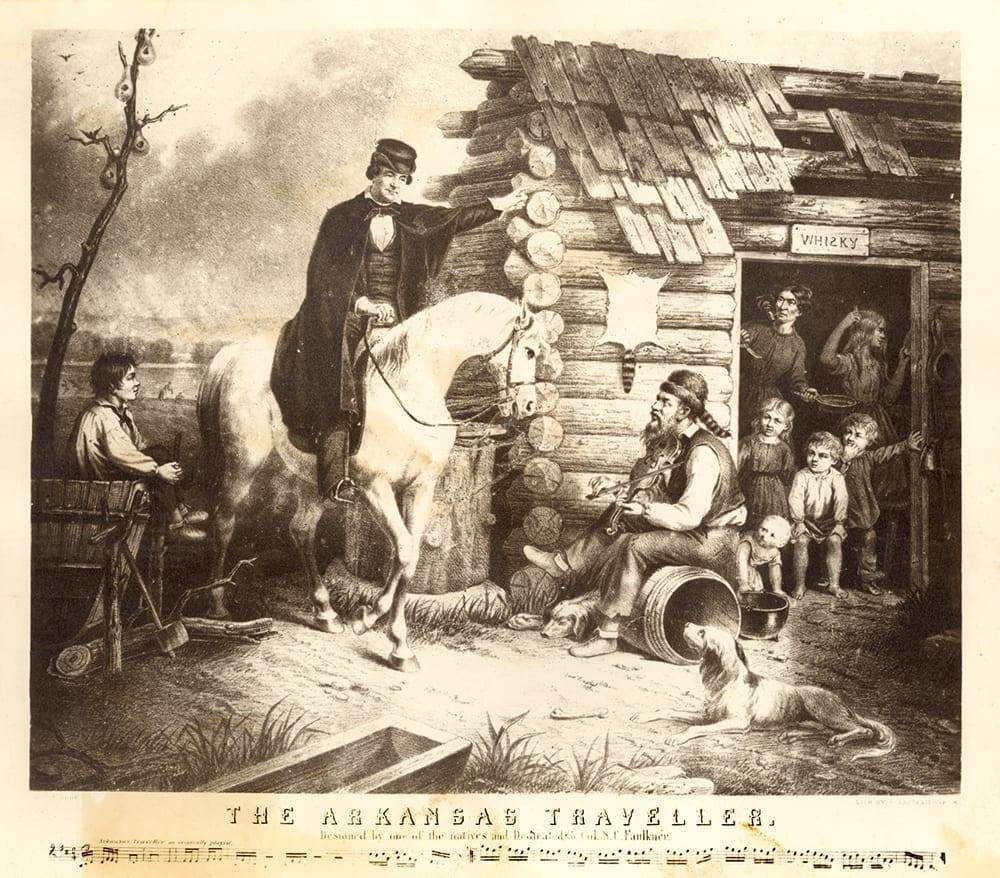

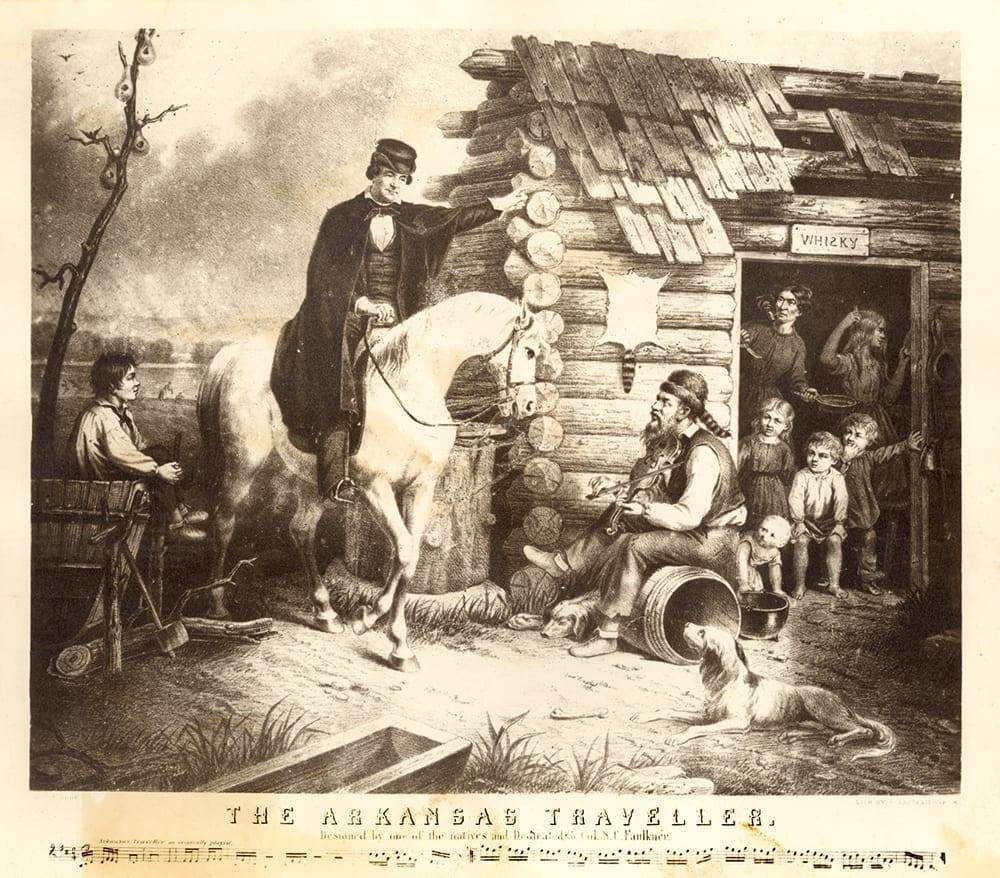

The Arkansas Traveler by Currier and Ives, 1870, after a painting by Edward Payson Washburn. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2345)

The log cabin has come to symbolize the Ozarks, in both positive and negative ways. It’s been used as a branding tool, a stereotype, and a way to communicate a sentimental sense of a simpler time.

In the mid 1800s stories and images depicting the “Arkansas Traveler” were popular nationwide. The tale made fun of a hapless wanderer coming across a shiftless family and their rude log cabin in the wilds of Arkansas. In the late 1960s investors built the backwoods theme park of Dogpatch over in Marble Falls (Newton and Boone Counties). Based on Al Capp’s hillbilly comic strip “Lil’ Abner,” the park featured numerous log cabins gathered from the surrounding hills. On the 1960s television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, the Clampett family so missed their Ozark home that they built a cabin behind their fancy mansion.

William Hope “Coin” Harvey of Monte Ne (Benton County) may have been the first person in the area to use a log building as a marketing tool. In 1905 he completed a massive log hotel known as Missouri Row as a way to attract visitors to his resort. Over in Western Grove (Newton County) in the 1920s, Mrs. Poort’s Tourist Court featured Adirondack-style cabins made of round logs for visitors. No doubt they were economical to build, but their rustic charm and novelty said “Ozark” to Grace Poort’s customers. For the past few decades the House of Webster in Rogers (Benton County) has used a log cabin as retail space to sell its line of preserves and other food products.

Log buildings can still be found, usually unoccupied, along back roads or preserved at area historical institutions. That they still exist today is a testament to the skilled craftsmen who built these sturdy structures for their families and communities, using a few simple tools and materials gathered from forest and field.

Icon of the Ozarks

The Fincher family by their single pen log cabin, near Maguiretown (Washington County), mid 1890s. From left: John, Nora, Indiana, Charles, and Kate Fincher. Tom Fincher Collection (S-83-139-13)

Life in a single-pen log cabin was cramped, especially for a large family. Eating, sleeping, and other activities all happened in the same space. Furniture and personal belongings, including clothes, were kept to a minimum. In a house with two pens, one served as a general living area while the other held the kitchen and dining room. Folks might sleep in either room or in a loft, if they had one. During summer, doors and windows were thrown open to catch a cooling breeze. When winter winds blew through the chinking, even a blazing fire might not keep the house warm enough.

Changing Times

Early Ozarkers were recyclers. Rather than build new houses, they added onto their existing homes. Cramped single pen cabins soon became dogtrots or double-pen houses. Lean-to rooms made of sawn boards were tacked on for additional space, further obscuring the footprint of the original pens. For added protection from the elements, wide weatherboards made of planked wood were attached horizontally to the home’s exterior.

As families prospered and earned enough cash to purchase milled lumber, they added siding and fancy trim to their home to give it a modern appearance. By the early 20th century many log homes had been transformed, buried deep within the walls of an enlarged, up-to-date house.

If a family built a new home, the old log building was often used as a farm building or for storage. In 1898 abandoned log cabins were pressed into service as temporary homes for the newest settlers to the Ozarks—the Italian immigrants of Tontitown (Washington County).

End of an Era

Log-home construction lessened by the 1880s, especially in the more populated areas of Northwest Arkansas. The availability of milled lumber, cash income, and modern architectural styles prompted the switch to the frame-style housing of today.

It wasn’t until the 1920s and 1930s that another wave of log-building construction began. As New York’s rustic Adirondack architectural style came into vogue nationwide, it was often used for vacation cottages. During the Great Depression, when several area state parks were constructed under the Works Progress Administration, recreational cabins and other structures were built using a simplified Lincoln Log-type architecture, along the lines of the Adirondack style. Impoverished families, especially in rural areas, were sometimes forced to build log homes for shelter. Compared to those of their ancestors, the structures were inelegant and crudely built. The log-building tradition had been lost.

An Icon of the Ozarks

The Arkansas Traveler by Currier and Ives, 1870, after a painting by Edward Payson Washburn. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2345)

The log cabin has come to symbolize the Ozarks, in both positive and negative ways. It’s been used as a branding tool, a stereotype, and a way to communicate a sentimental sense of a simpler time.

In the mid 1800s stories and images depicting the “Arkansas Traveler” were popular nationwide. The tale made fun of a hapless wanderer coming across a shiftless family and their rude log cabin in the wilds of Arkansas. In the late 1960s investors built the backwoods theme park of Dogpatch over in Marble Falls (Newton and Boone Counties). Based on Al Capp’s hillbilly comic strip “Lil’ Abner,” the park featured numerous log cabins gathered from the surrounding hills. On the 1960s television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, the Clampett family so missed their Ozark home that they built a cabin behind their fancy mansion.

William Hope “Coin” Harvey of Monte Ne (Benton County) may have been the first person in the area to use a log building as a marketing tool. In 1905 he completed a massive log hotel known as Missouri Row as a way to attract visitors to his resort. Over in Western Grove (Newton County) in the 1920s, Mrs. Poort’s Tourist Court featured Adirondack-style cabins made of round logs for visitors. No doubt they were economical to build, but their rustic charm and novelty said “Ozark” to Grace Poort’s customers. For the past few decades the House of Webster in Rogers (Benton County) has used a log cabin as retail space to sell its line of preserves and other food products.

Log buildings can still be found, usually unoccupied, along back roads or preserved at area historical institutions. That they still exist today is a testament to the skilled craftsmen who built these sturdy structures for their families and communities, using a few simple tools and materials gathered from forest and field.

Photo Gallery

Construction

Cabin raising at Onda community (also known as Dripping Springs) near Prairie Grove (Washington County), circa 1910. Lewis McAdoo (center, behind upright pole) and his son Ulysses (seated on log being raised, second from left). Ray McAdoo Collection (S-92-169-5)

When a cabin was built, the community came together to help. Men worked, woman cooked and visited, and children played. To build the walls, long skids made from young trees were angled against the structure. Logs were pushed and pulled up them into place. These logs are planked, meaning that only two (opposite) sides were hewn flat, rather than all four sides. Skill was needed to shape the ends of the logs with an ax in order to join the corners together.

James and Ann Eliza Counts McDonald, Thorney (Madison County), circa 1900. Gary King Collection (S-97-2-151)

A chopping ax was used to score the side of the log as part of the first step in shaping it. Once the scores had been made, the wood between them was chipped out and the side made flat with a broadax. The score marks are still visible on this cabin. The door is simple, made with sawn boards.

Granvil Jameson, Bowen Township (Madison County), circa 1911. Jerry Officer Collection (S-2000-1-131)

Half-dovetail corner notching was the most common form of notching in the Arkansas Ozarks. It created a sturdy corner. Once the logs were in place, chinking materials (big wood chips or shingles; see photo below) were wedged between the logs and covered with daubing, a lime mortar mixed with clay, mud, or sand. Sometimes only a mortar mix was used, which wasn’t as weather tight. In the top photo, the building appears to have interior sheathing made of wide boards. On the exterior, wood sticks were added between the logs to further keep out wind; they may have been daubed over at one time.

Fred, Martha, and Nellie Hann, Friendship community near West Fork (Washington County), circa 1907. Elsie Cress Young Collection (S-85-129-33)

Niccum family, Springdale (Washington County), 1900s. Nancy Moore Niccum (fourth from right) stands with her sons, Abe and John (third and eighth from right). Bobbie Lynch Collection (S-77-53-28)

The cabin on the left was probably built in the 1850s; the rough addition was added later. The fact that it’s sheathed with sawn lumber in a board-and-batten pattern may indicate a frame structure rather than log. Rather than build a second stone chimney, a metal flue from a wood stove pokes through the roof. Early Ozarkers often added to existing buildings rather than build new.

Building the Work and Play School, Delaney (Madison County), early 1930s. Mary Mullen Collection (S-2003-14)

In 1930 teacher Mary Guilbeau moved from Dallas to Delaney to establish a private school so rural Arkansas students could learn the classics along with their regular studies. She persuaded the folks in Delaney to donate land and build a log schoolhouse. Guilbeau especially admired the work of woodworker Jimmie Wilson who shaped the logs with a broadax. He’d mark the spot with his big toe and then move back just before the ax fell, whacking the exact spot where his toe had been. Unlike the log buildings of earlier generations, the school was built with round logs and saddle notches at the corners.

Single Pen

Single pen log cabin, possibly the Strain Community (Washington County), early 1900s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4816)

The single pen was a one-room structure with a chimney on the gable end. It’s possible that this cabin was built by the Strain family, which settled near the Middle Fork of the White River in the early 1830s. Like most homes at the time, the front door faced the road. Seen above the door are the ends of the floor joists for the second floor or loft. Half-dovetail notches are used at the corners.

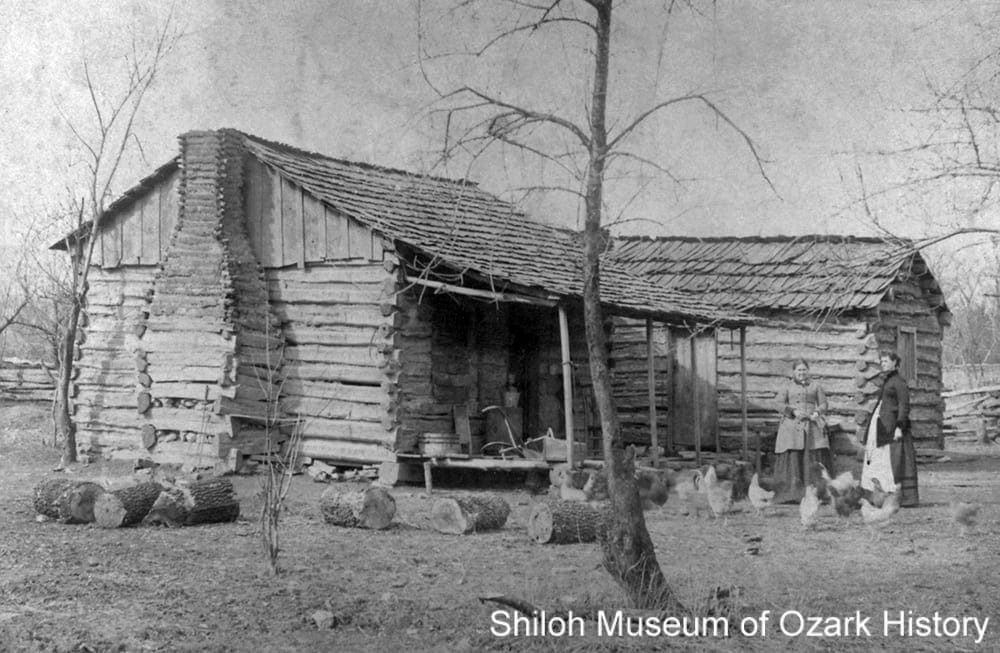

George Daniels’ single pen log cabin (with a second single pen built close by), near Sulphur Springs (Benton County), late 1890s. Lucy Daniels (left) with her daughter-in-law, Idonia. Jim Buckley Collection (S-85-60-2)

The stick-and-mud chimney with its clay lining was easy to build. Should the chimney catch on fire a long pole, kept nearby, was used to push the burning structure away from the house. The cabin on the left appears to use conventional rafters to support the roof. On the right, logs running the length of the cabin are used. The shingles are nailed directly to them. Overhanging log ends protrude from the building’s corners. Normally they would be trimmed flush with the wall to quickly shed rainwater.

Melania and Pier Antonio Maestri at their single pen log cabin, Tontitown (Washington County), about 1900. Richard Roso Collection (S-82-78-21)

In 1898 the Maestri family was among the first to settle Tontitown. They were part of a group of Italians who immigrated to Arkansas to begin a new life. They lived in abandoned cabins and outbuildings until they could build their own homes. Some families shared a single home or log barn. Seen above the door are the ends of the floor joists which have been mortised into the logs to create a second floor or loft. Half-dovetail notches are used at the corners. A second door, unusual for a home this size, aided cross ventilation.

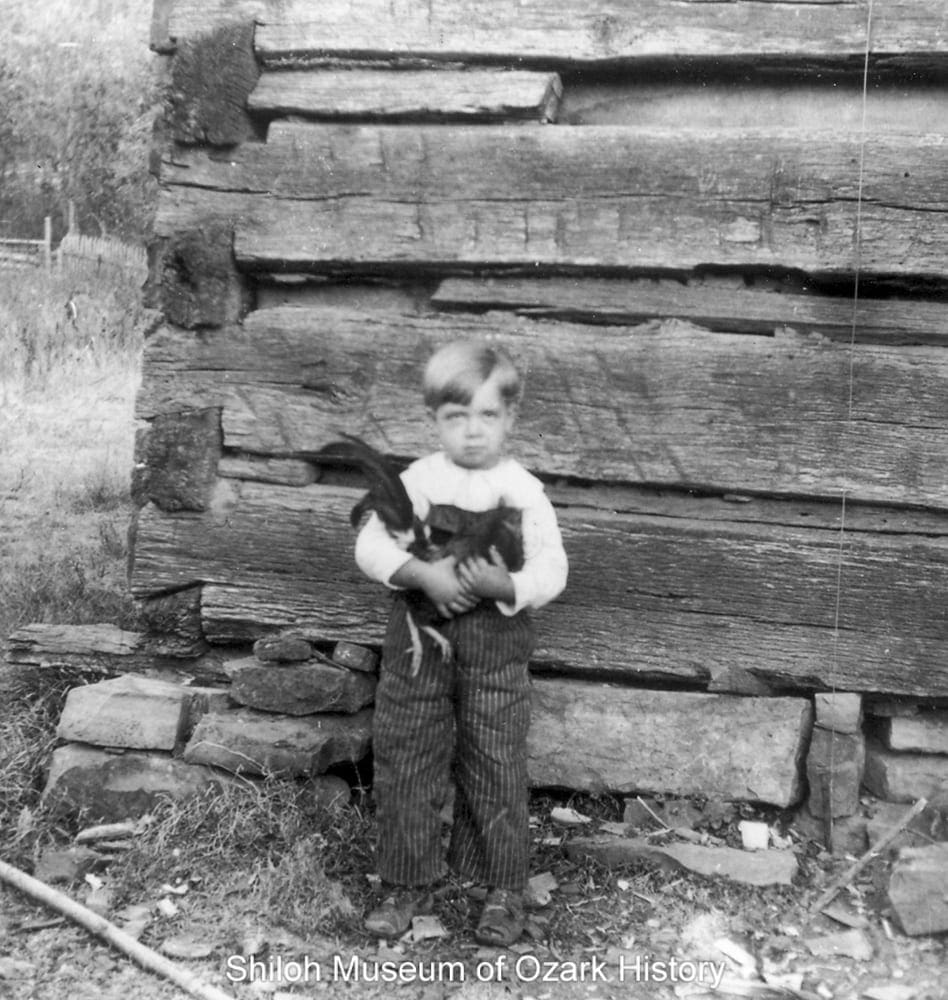

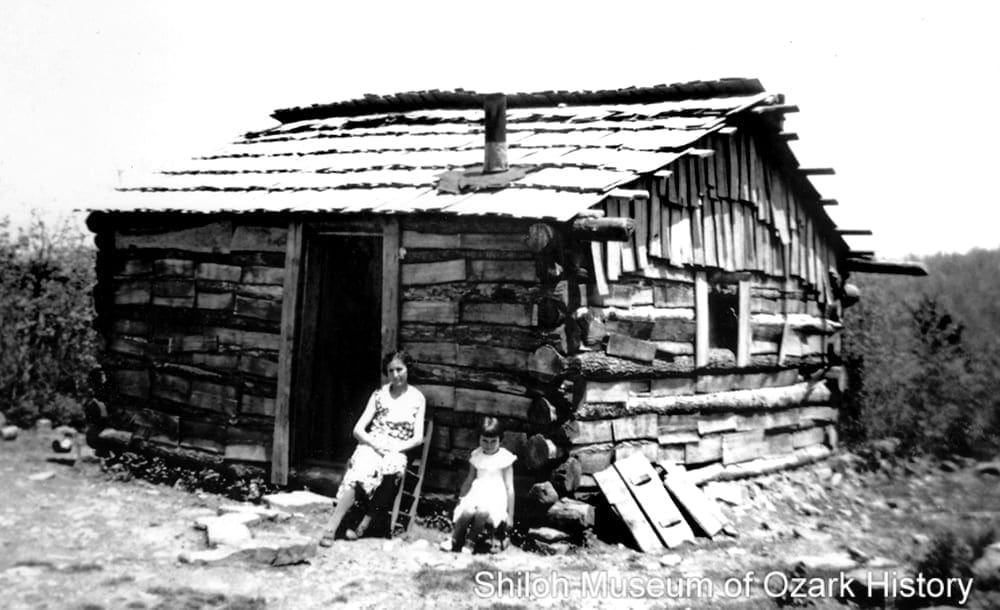

Argie Cooksey and her daughter Ivis, Newton County, 1933–1935. Opal and Ernest Nicholson, photographers. Katie McCoy Collection (S-95-181-84)

Mrs. Cooksey and another woman built this ramshackle house during the Great Depression, at a time when people made do however they could. While the structure doesn’t show the same level of construction skills as log cabins built a century earlier, no doubt it served as a welcome home.

Double Pen

John Latta’s two-story double pen log home, Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park (Washington County), about 1990. Mary McGimsey, photographer. Shiloh Museum Collection (S-90-24-1)

This impressive four-room structure was built in 1834 in the Vineyard community, not far from today’s border with Oklahoma. It was moved to the battlefield in 1958. Usually a double pen is a single-story building, made of two individual pens with chimneys on either side. In this case it may be that the pens were skillfully connected together, with only a single log wall between them. Latta and his enslaved workers, Dan and Ben, were talented craftsmen who built homes, cabinets, and wagons. The home’s original shingles, cut from unseasoned oak and boiled in tallow (animal fat) to make them water repellent, lasted over sixty years.

Samuel Merritt Bland’s home, Larue (Benton County, Arkansas), about 1903. Jewel Dye (left) with Amanda, Merritt, and Alonzo Bland. Betty Rendon Collection (S-2012-124-2)

The double doors and chimneys at both ends indicate this building was once a double pen log home. By adding clapboard siding and whitewashing the chimneys, the homeowner has updated the look of his home, making it seem like a newer, frame-style structure.

C. A. Linebarger’s summer home, Bella Vista (Benton County), late 1920s. Bella Vista Historical Museum Collection (S-82-199-105)

The front part of this two-story structure (originally a double pen) was built in 1853 by Jabez T. Hale. It featured four rooms upstairs and four downstairs. In 1926 Linebarger moved it a couple hundred yards to its present location, remodeled it (leaving only one front door), added on a fashionable Adirondack/Craftsmen-style entry, and built a large addition in the rear.

Saddlebag

Henry Webber’s saddlebag log home, Webber Mountain near West Fork (Washington County), about 1902. Washington County Observer/Vita Vines Collection (S-85-111-101)

The saddlebag was made of two pens with a single chimney between them. Although the image is faint, there appears to be an arched screen to keep out debris over the top of the chimney, which may actually be two chimneys placed back-to-back. The double front doors are typical of two-pen log buildings. Half-dovetail notches are used at the corners. A log outbuilding stands behind the house.

Dogtrot

George S. Crudup’s dogtrot home, Fayetteville (Washington County), about 1900. George (10th from left) with his siblings, children, and grandchildren. Karen Weiss Collection (S-2000-111-17)

The dogtrot was made of two single pens connected by a covered breezeway, with chimneys on the gable ends. Various clues indicate this image was taken behind the home—the covered well, the lack of doors, the small chimney (for a wood stove) poking through the roof, and the more-refined picket fence seen through the breezeway.

The John Calvin Stockburger family peeling apples, Winslow (Washington County), 1905. From left: Annie, Martha, Calvin (in front), and John. Robert G. Winn Collection (S-96-162-21)

The front of this dogtrot house has been sheathed in clapboards in an effort to modernize it, but the walls of the breezeway still show the home’s original log construction. On the porch and in the breezeway are chairs, wood boxes, and a basket, demonstrating how outdoor spaces were used for work, relaxation, visits with neighbors, and storage.

Miscellaneous Buildings

Robert Light’s log barn, Pleasant Hill Township (Newton County), 1912. Cora Humble Collection (S-88-135-6)

Barns and outbuildings were sometimes built quickly, without the precision that might go into a home. The main floor could be used for sheltering livestock and storing equipment and wagons. The loft was used to store hay. Roofs often extended far beyond the walls to provide additional shelter.

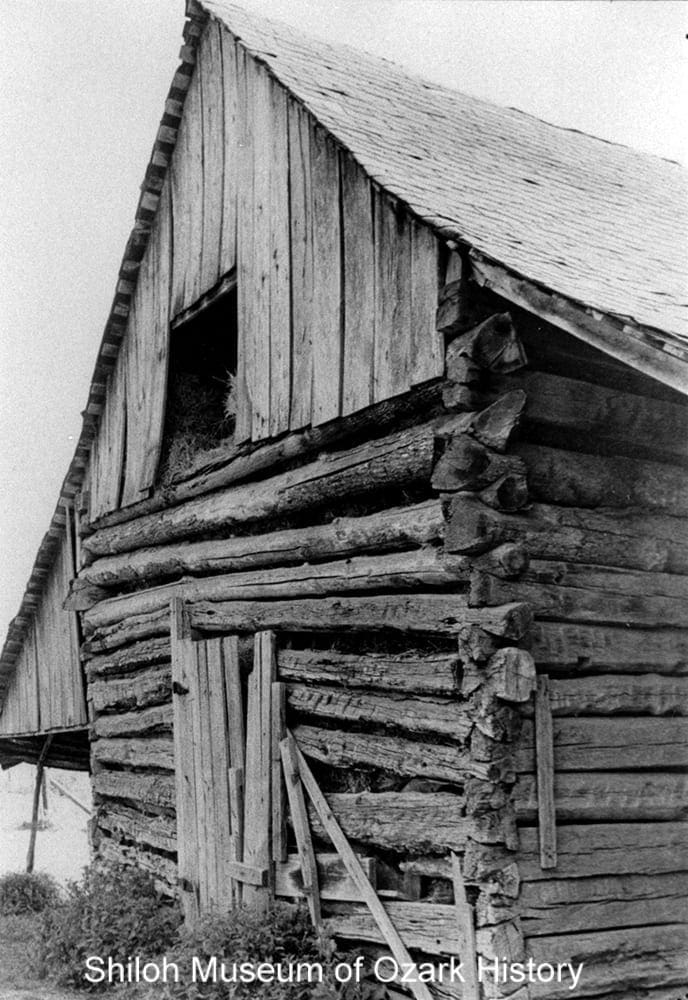

Nathan Combs’ log barn, Fayetteville (Washington County), about 1971. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-934)

Some of the logs for this barn may have come from Combs’ first home, built sometime around 1861. His original plan was to build a substantial two-story brick home (which he eventually did), but then came the turmoil of the Civil War. The barn has a mix of planked logs (hewn flat on two sides) and round logs, some still with their bark. The first rows of logs are joined with half-dovetail notched corners; further up some of the logs appear to be saddle notched. These details indicate that different hands worked on this structure over the years. The barn was torn down in the early 1990s.

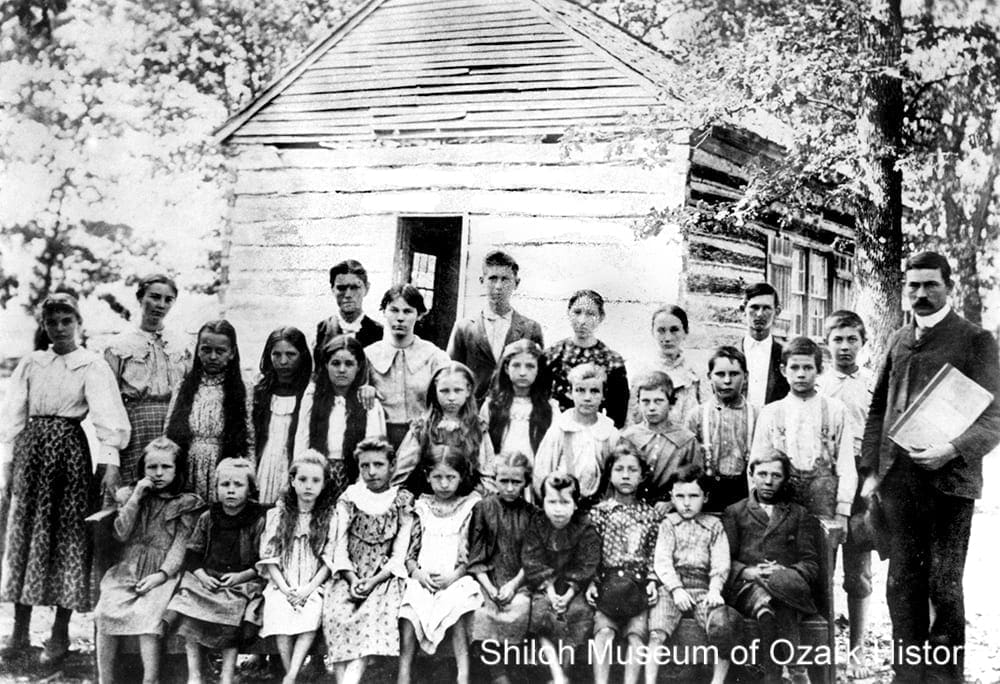

Black Oak School, near Elkins (Washington County), circa 1895. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1052)

While most homes had front doors along the length of the building, the doors to schools and churches were often placed on the short, gable-wall side to better accommodate rows of school desks and pews. The school was established sometime around 1883 and was also used as a church. The log building was replaced with a frame structure in 1907.

Missouri Row Hotel, Monte Ne (Benton County), circa 1908. Speece and Aaron, photographers. Mrs. Kenneth L. Tillotson Collection (S-90-91-9)

Missouri Row was designed by noted Rogers architect A. O. Clarke. Completed in 1905, the building was 46-feet wide, 305-feet long, and used 8,000 logs. It and its sister, Oklahoma Row, built a few years later, were said to be the largest log buildings in the world. The remains of the log portion of Oklahoma Row can be found up the road from its original location near the Beaver Lake boat ramp at Monte Ne.

Credits

“A Way of Life in Early Shiloh.” Shiloh Springdale, 1878-1978. Springdale, Arkansas, Centennial Committee, 1978.

“Colorful Ozark Landmark [Latta House] is Saved for Posterity,” unknown undated newspaper, probably mid 1950s. Shiloh Museum research files.

Barnett, Kathryn Robbins. “Our Bella Vista Community Then and Now.” Benton County Pioneer Vol. 16, No. 4 (Fall 1971).

Deane, Ernie. “Pioneer Village Growing at Prairie Grove.” Arkansas Gazette, 5-15-1960.

Donat, Pat. “An Ante-Bellum Home.” Flashback (Washington County Historical Society) Vol. 21, No. 1 (March 1971).

Faris, Paul. Ozark Log Cabin Folks: The Way They Were. Rose Publishing Co.: Little Rock, 1983.

Ford, Edsel. “Park Village: Prairie Grove residents are reassembling log cabins in the battlefield park area.” Arkansas Democrat, 8-31-1958.

Hogue, Wayman. Back Yonder. Knickerbocker Press: New Rochelle, NY, 1932.

Lord, Allyn, and the Rogers Historical Museum. Historic Monte Ne. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC, 2006.

Moore, Marjorie. “How the Pioneers Lived.” Flashback (Washington County Historical Society) Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 1955).

Phillips, George H., ed. The Bella Vista Story. Bella Vista Historical Society: Bella Vista, AR, 1980.

Rogers Daily News. “Rural life in county was typical.” 6-29-1976.

Salsbury, Clarice. “Black Oak 41.” School Days, School Days . . . The History of Education in Washington County, 1830-1950. Washington County Retired Teachers Association, circa 1986.

Sizemore, Jean. Ozark Vernacular Houses: A Study of Rural Homeplaces in the Arkansas Ozarks, 1830-1930. University of Arkansas Press: Fayetteville, 1994.

Thompson, Alan. Email to Shiloh Museum staff regarding Latta House, 10-28-2012.

Ulmer, Louise. “Mrs. Guilbeau’s Work and Play School,” Louise Ulmer, Shiloh Scrapbook (Shiloh Museum of Ozark History) Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring 2004).

Wigginton, Eliot, ed. “Building a Log Cabin.” The Foxfire Book. Anchor Books: New York, 1972.

Wolf, John Quincy Sr. Life in the Leatherwoods: An Ozark Boyhood Remembered. August House: Little Rock, 1988.

Worthen, William B. “Arkansas Traveler.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas [accessed 10/2012]