Collector's Day: Virtual Edition

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the interest of the health and safety of our visitors, staff, and volunteers, our annual “Cabin Fever Reliever” open house and collector’s day held each January has gone virtual for 2021. Here on our website we’re featuring items from the museum’s founding collection, which belonged to Springdale attorney and municipal judge Guy Howard (1876–1965), known to Springdale residents in his day as “the Judge.”

Howard began collecting “arrowheads” as a boy and spent the rest of his life amassing a huge collection of prehistoric and historic Native American artifacts and more. Over the years, he welcomed people into his Springdale home to view the many thousands of artifacts on display. The Judge and his collection became a local legend. Shortly before Howard died in 1965, the Springdale City Council voted to purchase his collection, planting the seeds for the creation of the Shiloh Museum.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the interest of the health and safety of our visitors, staff, and volunteers, our annual “Cabin Fever Reliever” open house and collector’s day held each January has gone virtual for 2021. Here on our website we’re featuring items from the museum’s founding collection, which belonged to Springdale attorney and municipal judge Guy Howard (1876–1965), known to Springdale residents in his day as “the Judge.”

Howard began collecting “arrowheads” as a boy and spent the rest of his life amassing a huge collection of prehistoric and historic Native American artifacts and more. Over the years, he welcomed people into his Springdale home to view the many thousands of artifacts on display. The Judge and his collection became a local legend. Shortly before Howard died in 1965, the Springdale City Council voted to purchase his collection, planting the seeds for the creation of the Shiloh Museum.

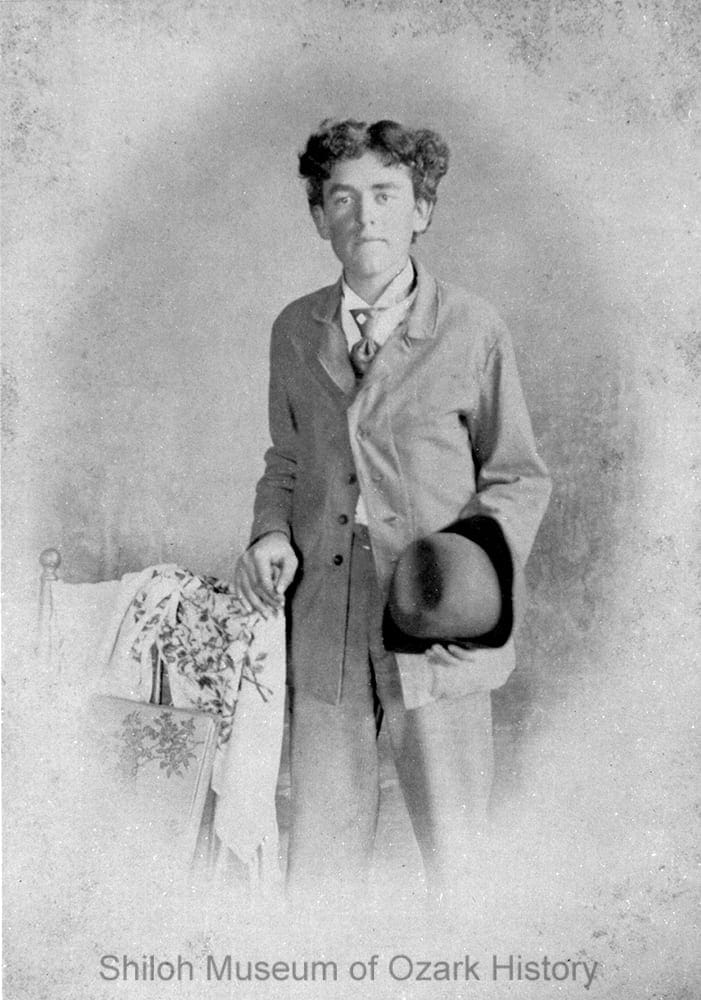

The Youngster

Howard family members at the Amos Howard home east of present-day Springdale, 1891. Guy Howard is in the front row, wearing a dark shirt. W. G. Howard Collection (S-71-5-3)

In 1881 a five-year-old Nebraska boy found an “arrowhead” in the family garden, sparking a lifelong interest in Native American artifacts. When the Howard family moved to Springdale by covered wagon in the early 1890s, young Guy Howard brought a box of curiosities with him. Imagine his delight upon finding the Ozarks rich in Native American history. His collection grew and grew.

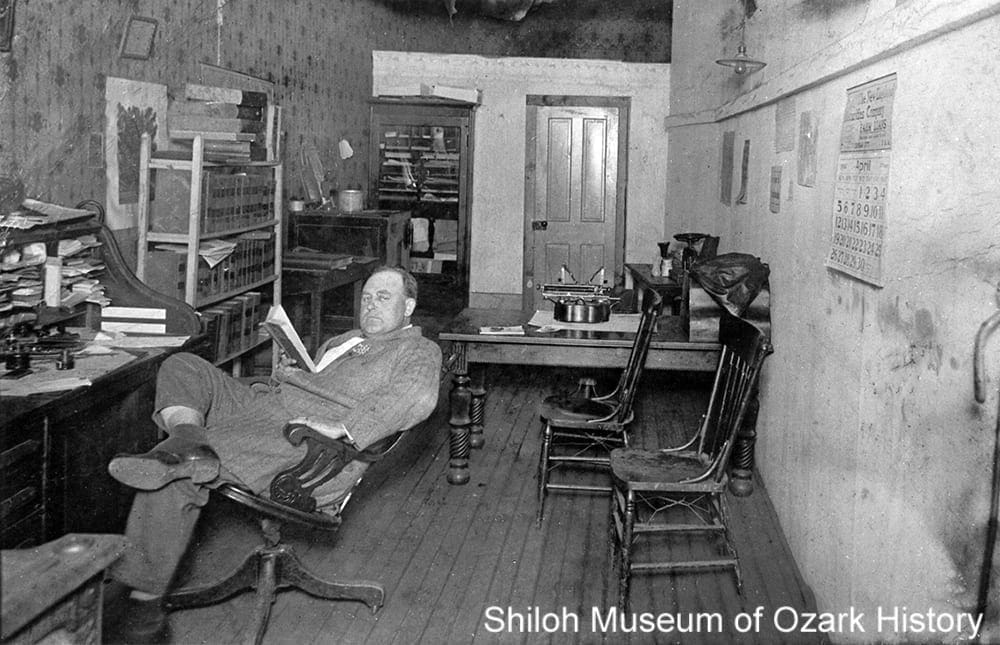

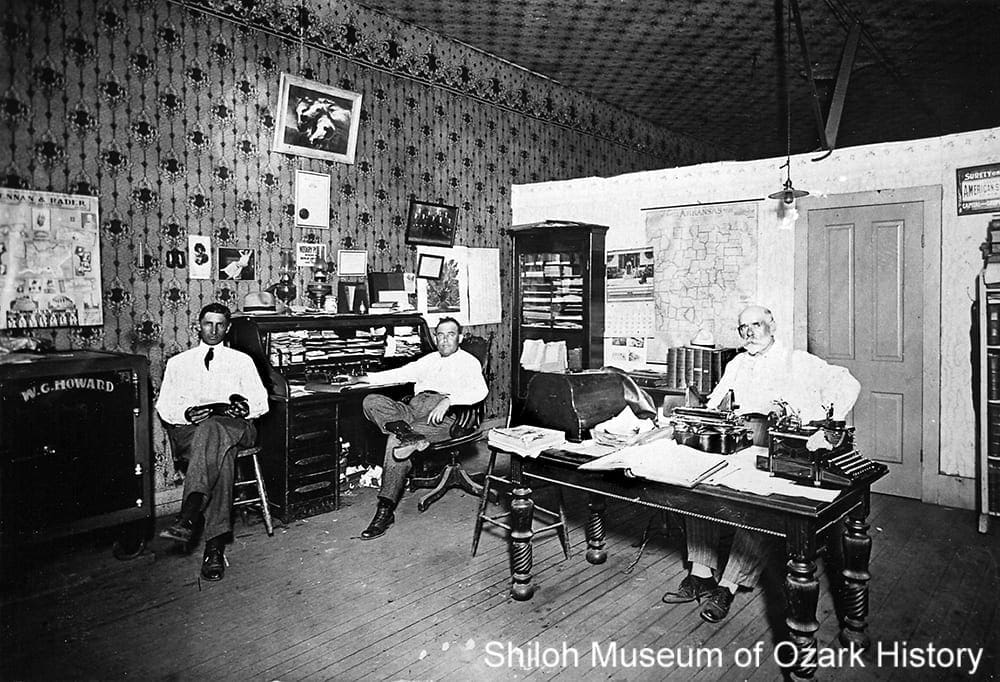

The Judge

A man from another era, Guy Howard was “the last of the old-time attorneys,” as one Springdale resident put it. Born in 1876, he formed his outlook and habits in a stiff-collared world that he never left far behind. Howard’s formal schooling ended before he arrived in Springdale with his parents and two sisters about 1890. He entered the legal profession by “reading” (apprenticing) under two Springdale attorneys, passing the state bar exam in 1907. He set up a small office above Penrod’s Café on Emma Avenue (near the present-day Emma Avenue Bar and Tap).

Howard was a creature of habit. Those who remember him say he always wore a white shirt, dark pants, and white hat. He walked the same six-block route to work, making the same stops each day. One stop was Joyce’s Drug Store on Emma where he placed a nickel on the glass counter and waited for a fresh cigar.

Howard was Springdale city attorney during World War I and mayor from 1938 to 1944. There were about 3,000 people in Springdale at the time. But Howard and the city council faced questions and problems that are familiar to us today. They purchased a rock crusher for street repair, applied for federal grants for the water works, regulated pets, relocated the jail, helped the library repair its roof, organized a city-wide clean-up, watched over the distribution of garments to citizens in need, set salaries for the nine or so city employees, and much, much more. During his time as municipal judge in the early 1950s, Howard had a reputation for being tough. From that point on he was known simply as “the Judge,” the epitaph inscribed on his Bluff Cemetery tombstone.

The Collector

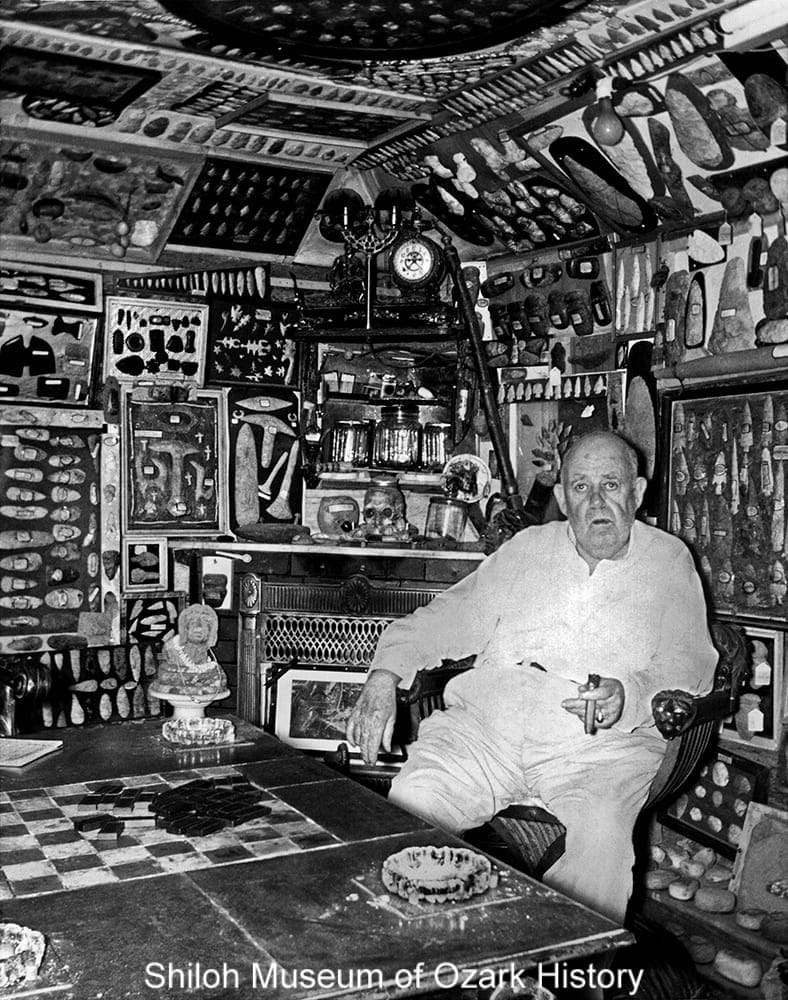

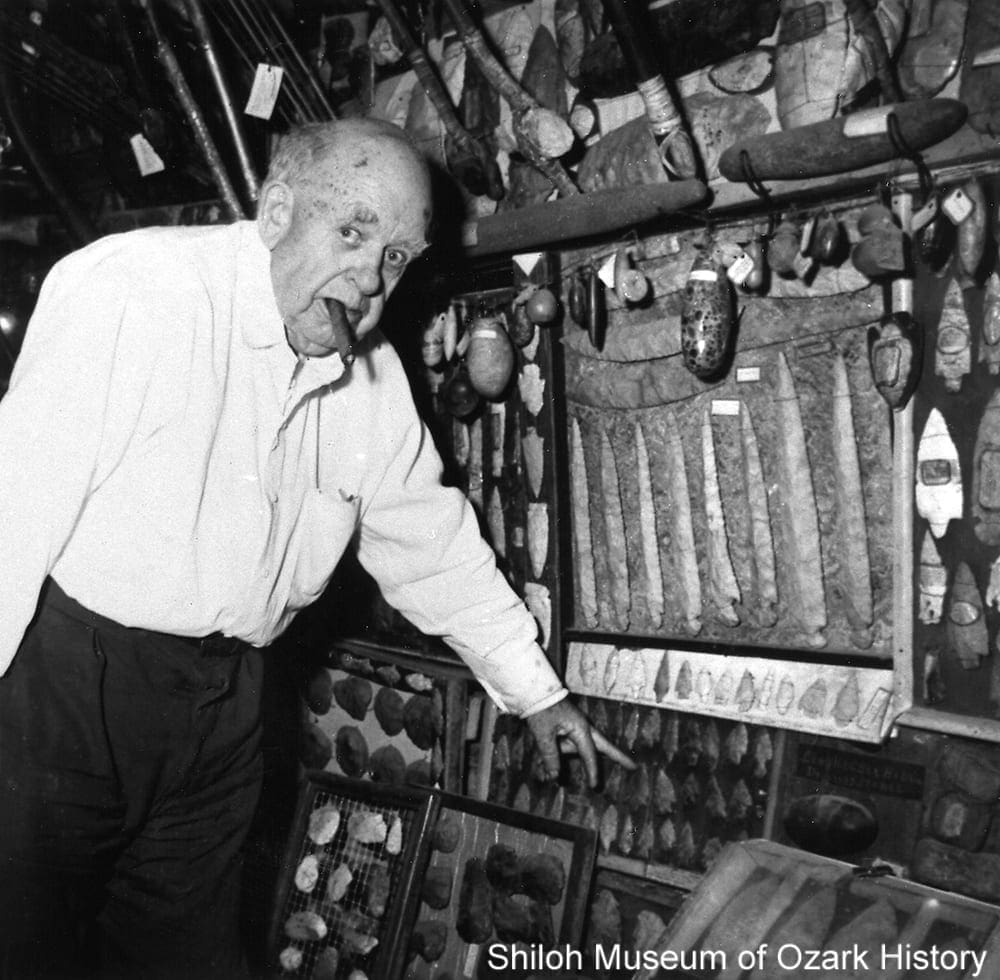

Guy Howard pointing to the artifact that started his collection, 1958. The photo was likely taken by University of Arkansas student Joyce Jenkins as part of a project for Mary Parler’s folklore class. Guy Howard Collection (S-93-41-52)

“I’ve made my $20, so I’m going home,” Guy Howard once explained to a passerby as he left his law office a little early. He said he didn’t think anyone should make more than $20 in a day!

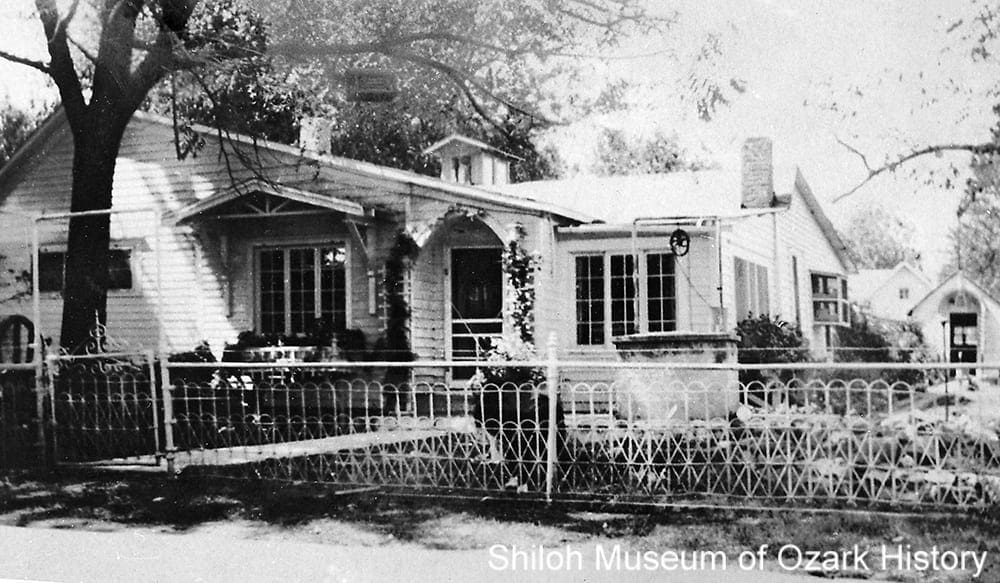

Howard enjoyed his home at 502 Price Street which he shared with his sisters, Lillian and Eva. Lillian kept the house, which was never locked, and Eva worked at Washington County Abstract. Unmarried, the three looked after one another.

Lillian collected books and Eva collected teapots, but the collection that dominated their lives belonged to the Judge. It took over the living room, an upstairs den, the garage, the workshop, his Emma Avenue law office, and finally a cabin on Hickory Creek.

Howard spent hours in his backyard workshop creating ways to display his treasures. He placed stone points within frames, which he nailed to the walls and ceilings, mounting some in certain ways to show how they were used. He painted a vine to look like a snake and created imaginary creatures from tree knots. Then he made sure that there was a story to tell about each item.

For three decades school classes, Boy Scouts, families, and strangers visited the Howard home to see and hear about the strange and wonderful things. In a very real sense the roots of the present Shiloh Museum were in Guy Howard’s astonishing exhibits and informal tours.

The Museum

Shiloh Museum curator Linda Allen at her desk alongside artifacts from the Guy Howard Collection, January 1969. At that time the museum was housed in the old Springdale Public Library building. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN-1-1969-5)

By the mid-1950s Lillian, Eva, and Guy Howard began feeling their old age. None of them ever made a lot of money, and they were simply not well prepared for “retirement.” Howard decided he needed to sell his famous collection to make ends meet.

Springdale city officials, some of whom had visited his museum as youngsters, did not want the artifacts to get away. As one explained, they also wanted to help Howard, who had worked for the city “practically for nothing” most of his life. In 1965 the Springdale City Council purchased Howard’s collection for $15,000.

In 1966 the Northwest Arkansas Archeological Society, with help from the University of Arkansas Museum, volunteered to organize the Guy Howard Collection and prepare it for exhibition in the old Springdale Public Library building, which was to be repurposed as the new Shiloh Museum. Larry Swaim, president of the society, said members met evenings and weekends for more than a year cleaning, studying, and sorting the materials.

The volunteers called on experts to authenticate the collection, which included a mixture of authentic items, authentic items that had been altered, and frauds. Most of the frauds were cleverly crafted and the archeologists wondered whether Howard knew that these were frauds when he acquired them. Among the experts who worked on the project were archeologists Gregory Perino (Gilcrease Museum), Hester Davis (state archeologist of Arkansas), Jerry Hilliard (Arkansas Archeological Survey), and Robert Lafferty III (Mid-Continental Research Associates), along with Don R. Dickson, a regional expert on archeology and flint-knapping; and Dr. Frederick Dockstader, a noted authority on Native American art.

A museum board was appointed, and Linda Allen was hired as curator. On September 7, 1968, the doors of the Shiloh Museum were opened to the public for the first time. As the museum’s emphasis on local history grew over the years, the Howard Collection became less prominent. Today some of his collections are on display in our Native American exhibit.

The Responsibility

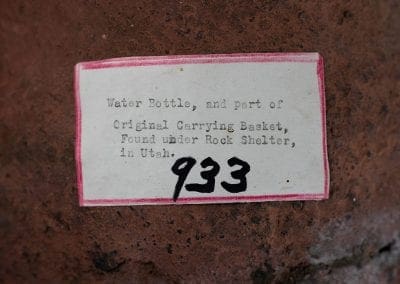

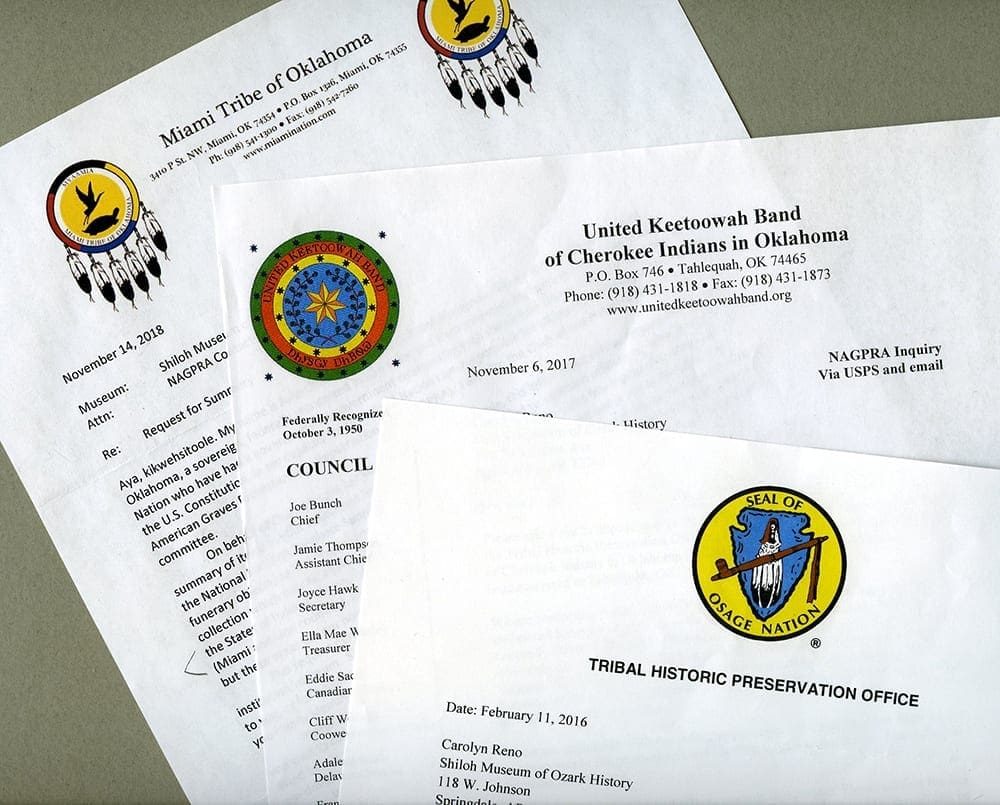

Letters sent by tribal historic preservation officers to the Shiloh Museum regarding human remains, associated funerary objects, or objects of cultural patrimony in its collection, 2016–2018.

When Guy Howard amassed his collection, many white folks thought nothing of removing Native American cultural objects and human remains from the landscape, whether legally or illegally. Seen as a dying culture, “Indians” were considered a relic of the past, whose concerns about their heritage didn’t matter. Howard was no different. His collection contains human remains and may include sacred and funerary objects. Today’s professional archeologists, academics, and museum curators are respectful of Native Americans and their culture.

In 1990 Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) to provide for “the repatriation and disposition of certain Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.” Museums and other institutions with Native American collections were required by the government to survey and report their holdings to the federal government and affiliated tribes. The Shiloh Museum submitted materials from the Guy Howard Collection and over the years has worked with several tribes—in particular, the Osage and Caddo Nations—regarding repatriation. More information about NAGPRA

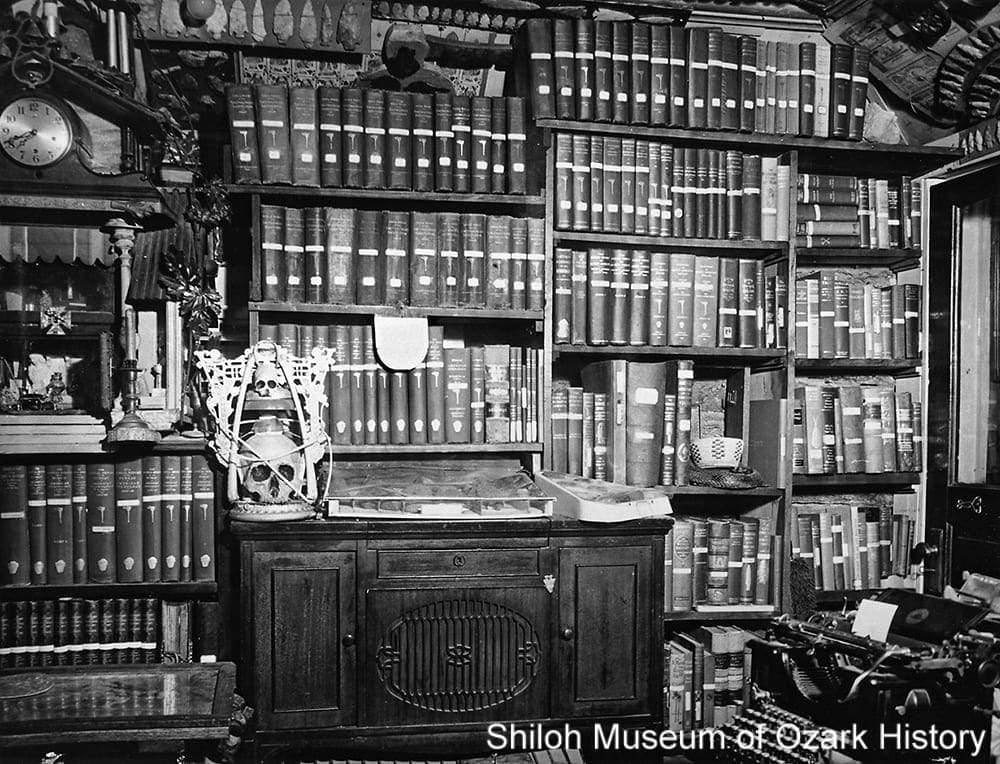

The photos below were taken inside the Howard home shortly before the City of Springdale purchased Guy Howard’s collection in 1965. They offer a glimpse of the amazing number of artifacts Howard collected and displayed floor-to-ceiling, and in some cases, including the ceiling! NOTE: Click on a photo to view an enlarged version.

Selections from the Guy Howard Collection

Beads, Spiro Mounds, Spiro, Oklahoma. Spiro Mounds, a key prehistoric American Indian site, consists of twelve mounds built between 850 and 1450 AD. It has yielded significant artifacts of Mississippian Culture. The site remained intact until 1917, when Joseph Thoburn tested Ward Mound One, a buried house mound. Between 1933 and 1935, the Pocola Mining Company dug indiscriminately in the Craig Mound, destroying about one-third of it and selling off thousands of artifacts. Scientific research conducted by the University of Oklahoma began in 1936. Privately owned until the mid-1960s, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers purchased the land with the intent of creating a national park, which never came to be. Through the efforts of the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey, the site became Spiro Mounds Archaeological State Park in 1978. Learn more about Spiro Mounds.

Beads, Spiro Mounds, Spiro, Oklahoma. Spiro Mounds, a key prehistoric American Indian site, consists of twelve mounds built between 850 and 1450 AD. It has yielded significant artifacts of Mississippian Culture. The site remained intact until 1917, when Joseph Thoburn tested Ward Mound One, a buried house mound. Between 1933 and 1935, the Pocola Mining Company dug indiscriminately in the Craig Mound, destroying about one-third of it and selling off thousands of artifacts. Scientific research conducted by the University of Oklahoma began in 1936. Privately owned until the mid-1960s, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers purchased the land with the intent of creating a national park, which never came to be. Through the efforts of the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey, the site became Spiro Mounds Archaeological State Park in 1978. Learn more about Spiro Mounds.

Cherokee or Creek stickball sticks. The Native American game of stickball began in prehistoric times as a way to settle disputes without going to war. The Cherokee word for the game is A-ne-jo-di, “little brother of war.” Stickball, which uses two sticks to hold and throw the ball, is similar to lacrosse, which uses only one stick. Stickball was and is played by Southeastern tribes, including the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole.

Cherokee or Creek stickball sticks. The Native American game of stickball began in prehistoric times as a way to settle disputes without going to war. The Cherokee word for the game is A-ne-jo-di, “little brother of war.” Stickball, which uses two sticks to hold and throw the ball, is similar to lacrosse, which uses only one stick. Stickball was and is played by Southeastern tribes, including the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole.

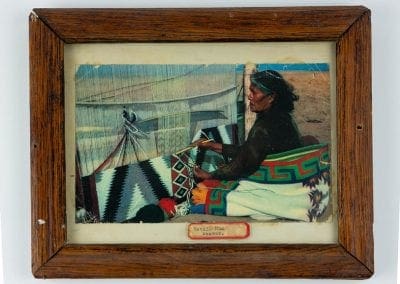

“What Next” plate, Harker Pottery Company, East Liverpool, Ohio, circa 1912. In 1792, U.S. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson designed a medal featuring an image of a Native American woman in a feather crown to give to visiting dignitaries. From that point on, images of Native Americans—often stereotypical or mythical—have been used in commercial art and advertising. Besides authentic Native American material culture, Guy Howard also collected these types of items.

“What Next” plate, Harker Pottery Company, East Liverpool, Ohio, circa 1912. In 1792, U.S. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson designed a medal featuring an image of a Native American woman in a feather crown to give to visiting dignitaries. From that point on, images of Native Americans—often stereotypical or mythical—have been used in commercial art and advertising. Besides authentic Native American material culture, Guy Howard also collected these types of items.

War clubs, 1880 and 1900. Used as a close-contact weapon, war clubs were made of hard rocks attached to hardwood handles and covered in buckskin or rawhide. The Gilcrease Museum identifies war clubs similar to these as 19th century Great Plains.

War clubs, 1880 and 1900. Used as a close-contact weapon, war clubs were made of hard rocks attached to hardwood handles and covered in buckskin or rawhide. The Gilcrease Museum identifies war clubs similar to these as 19th century Great Plains.

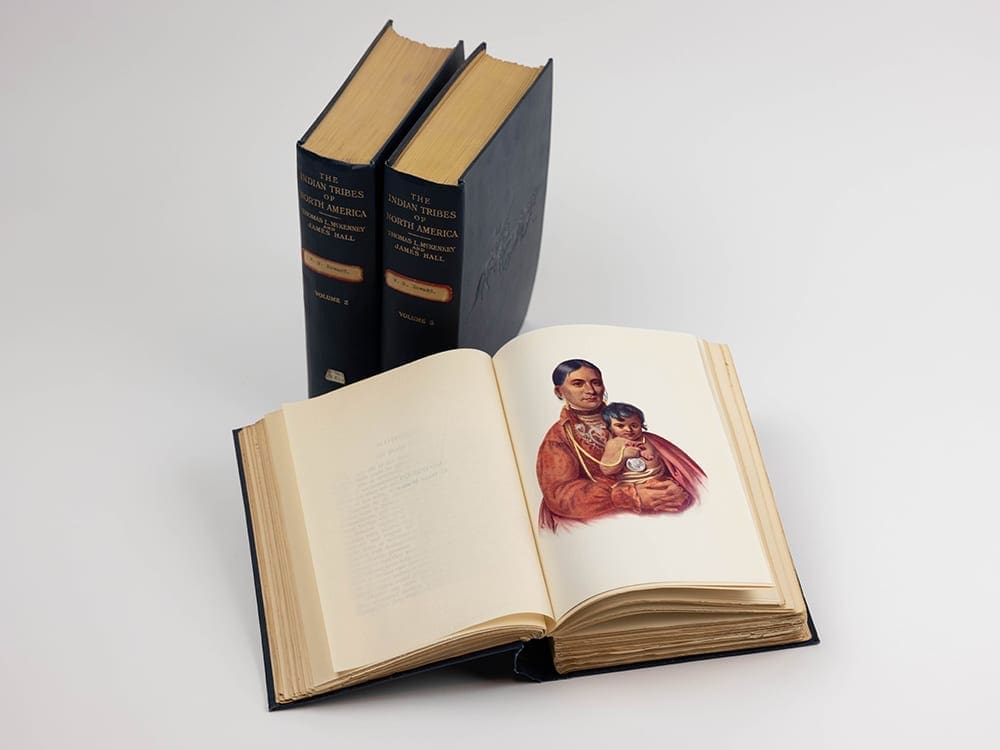

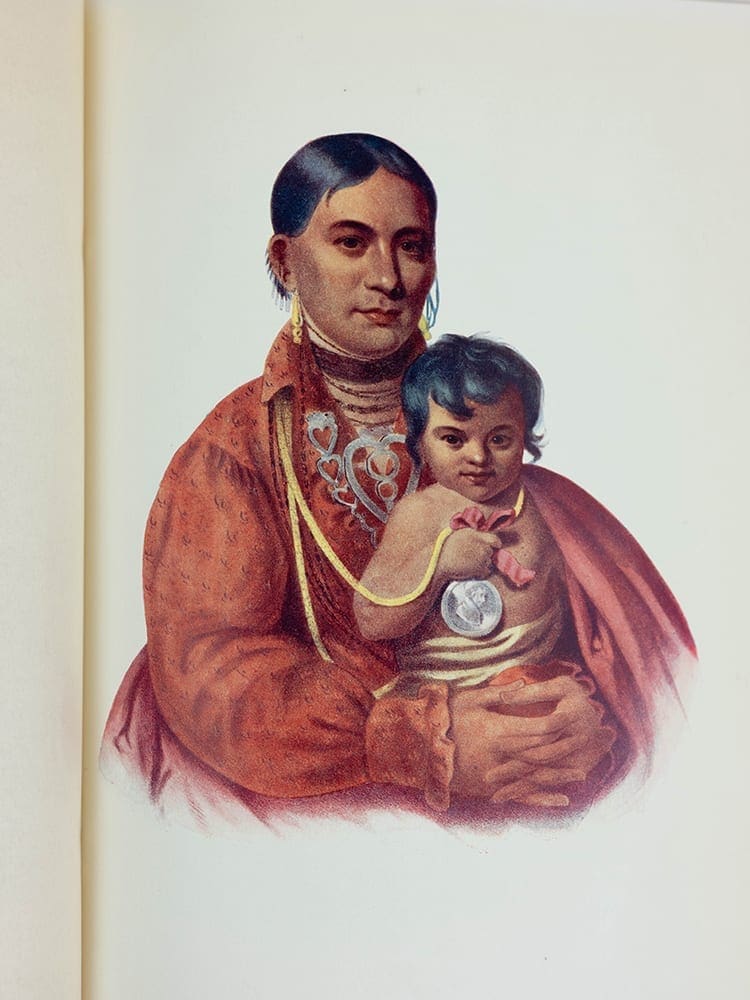

“Portrait of Mohongo, an Osage woman,” bookplate from The Indian Tribes of North America: Volume I by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, published by John Grant, Edinburgh, 1934. The Indian Tribes of North America, originally published in three folio volumes in 1836, 1838, and 1844, contains portraits of notable Native Americans of the era along with biographical information. The original books were the project of Thomas McKenney, begun when he was U.S. Superintendent of Indian Trade and continued when he became head of the Office of Indian Affairs. Worried about the fate of Native Americans as European-American society expanded, McKenney wanted to preserve the images of prominent members of tribes “in the archives of the Government.”

“Portrait of Mohongo, an Osage woman,” bookplate from The Indian Tribes of North America: Volume I by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, published by John Grant, Edinburgh, 1934. The Indian Tribes of North America, originally published in three folio volumes in 1836, 1838, and 1844, contains portraits of notable Native Americans of the era along with biographical information. The original books were the project of Thomas McKenney, begun when he was U.S. Superintendent of Indian Trade and continued when he became head of the Office of Indian Affairs. Worried about the fate of Native Americans as European-American society expanded, McKenney wanted to preserve the images of prominent members of tribes “in the archives of the Government.”

Mohongo, the subject of this portrait, has a compelling story. In 1827, she and her husband were part of a group of Osage Indians persuaded by a French con artist named David Delaunay into traveling with him to Europe, where they were essentially put on display for the fascination of European audiences. When Delaunay ran out of money, he abandoned the Osages in Paris. The Marquis de Lafayette heard of their plight and paid for their voyage to America in 1829. During that time, Mohongo’s husband died of smallpox. Left again in dire conditions in Norfolk, Virginia, Thomas McKenney, then the director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, came to the group’s aid and brought them to Washington, DC. In 1830, McKenney commissioned artist Charles Bird King to paint a portrait of Mohongo and her child. In the portrait, Mohongo’s child plays with a peace medal given to Mohongo by President Andrew Jackson.

Guy Howard kept an extensive library of reference material covering prehistoric and Native American culture and history. The collection contains 260 books and pamphlets and includes fifty years of both the annual reports of the Smithsonian Institution starting in 1896 and the Bureau of American Ethnology’s annual reports and bulletins from the 1880s to the 1920s.

Mohongo, the subject of this portrait, has a compelling story. In 1827, she and her husband were part of a group of Osage Indians persuaded by a French con artist named David Delaunay into traveling with him to Europe, where they were essentially put on display for the fascination of European audiences. When Delaunay ran out of money, he abandoned the Osages in Paris. The Marquis de Lafayette heard of their plight and paid for their voyage to America in 1829. During that time, Mohongo’s husband died of smallpox. Left again in dire conditions in Norfolk, Virginia, Thomas McKenney, then the director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, came to the group’s aid and brought them to Washington, DC. In 1830, McKenney commissioned artist Charles Bird King to paint a portrait of Mohongo and her child. In the portrait, Mohongo’s child plays with a peace medal given to Mohongo by President Andrew Jackson.

Guy Howard kept an extensive library of reference material covering prehistoric and Native American culture and history. The collection contains 260 books and pamphlets and includes fifty years of both the annual reports of the Smithsonian Institution starting in 1896 and the Bureau of American Ethnology’s annual reports and bulletins from the 1880s to the 1920s.

14

Projectile points. From left: Williams, 4000 BC–1000 AD; Stealth, Late Archaic, 3500 BC; Williams, 4000 BC–1000 AD; Standlee/Langtry (Texas), Middle Woodland, 230 BC–70 AD.

16

Knives. From left: Type unknown, southwest Arkansas; type unknown, southwest Arkansas; Harahey, origin unknown; type unknown, Clark County, Arkansas.

20

Mano and metate, Benton County. These stone tools were used to grind nuts into powder and corn into meal.

More from the Guy Howard Collection can be seen in our Artifact of the Month Archive:

Chess pieces

Powwow souvenir badge