Bridging the Gap

Bridging the Gap

Online Exhibit

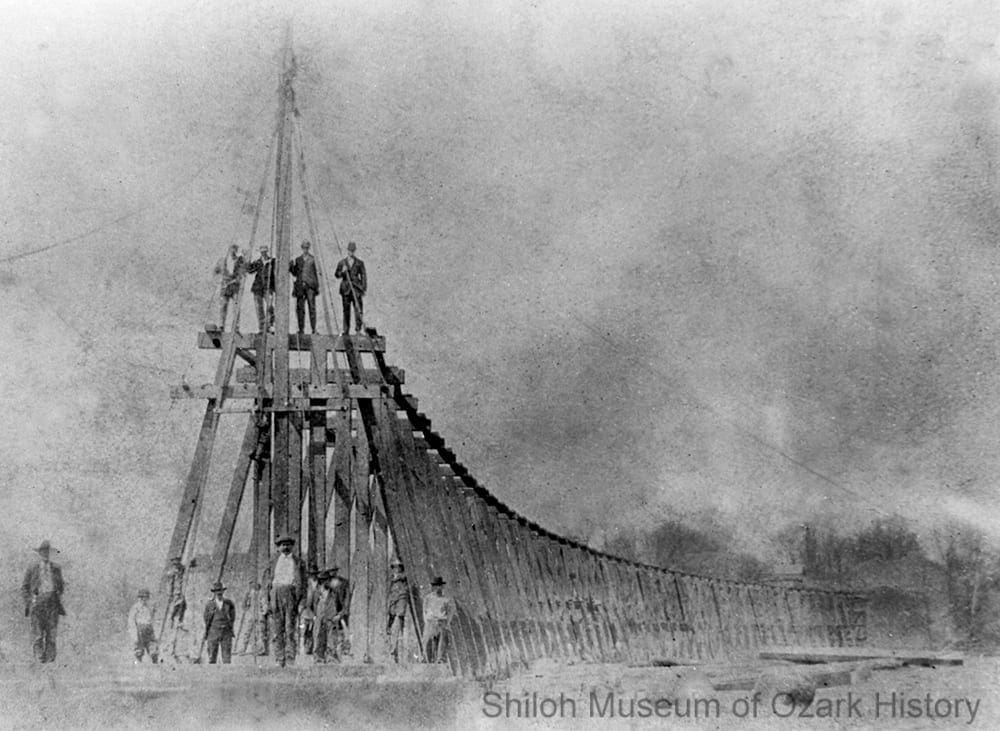

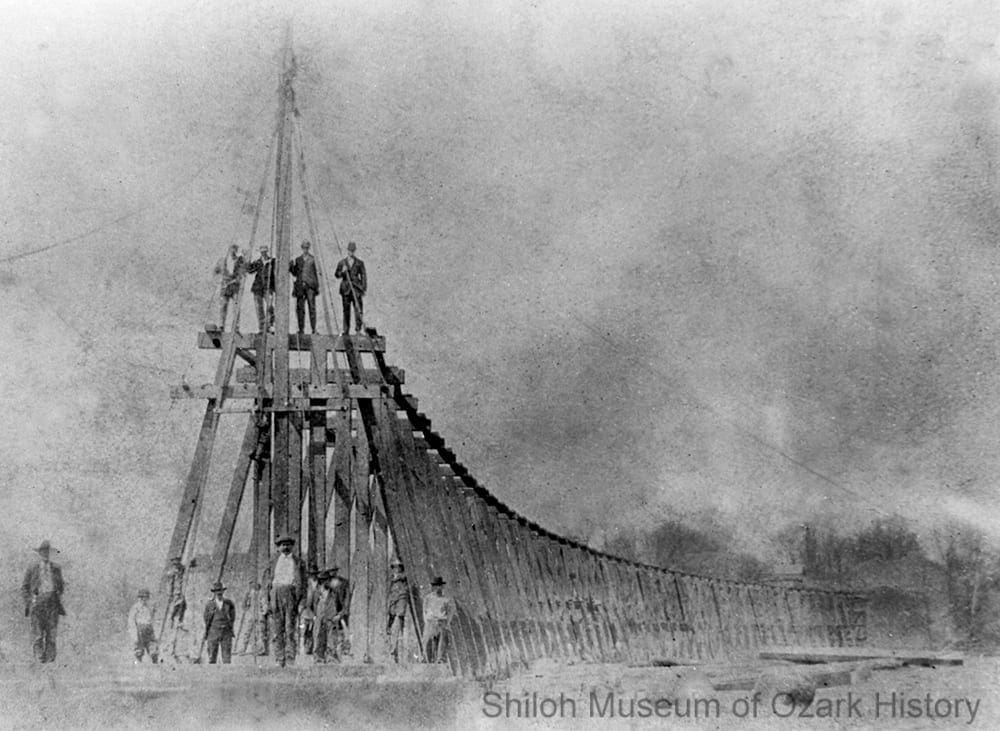

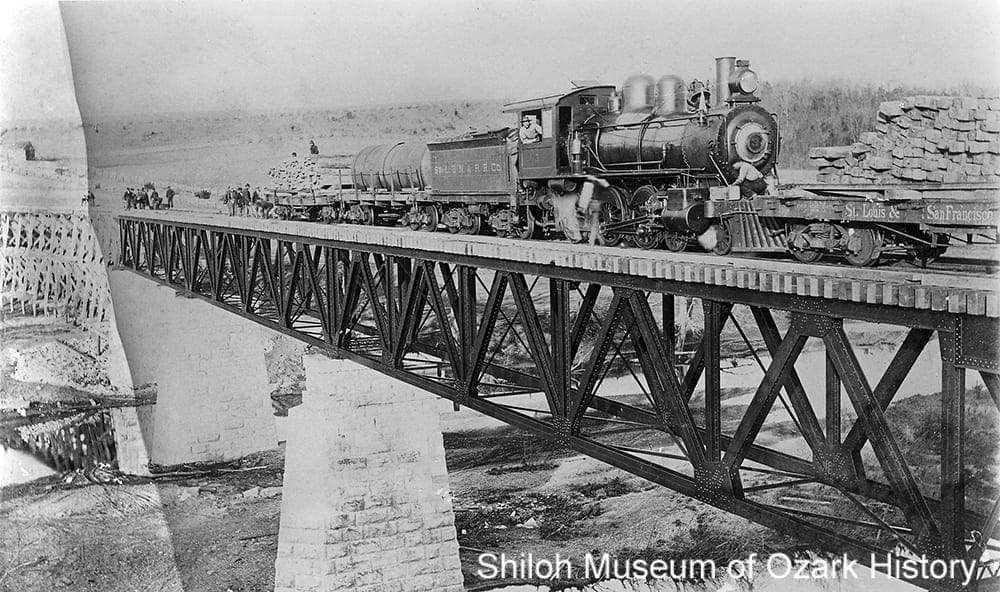

Trestle construction on the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway, Brightwater (Benton County), 1881. Robert G. Winn Collection (S-84-199-70)

When was the last time you crossed a bridge and paid attention to it? Really paid attention? It’s probably been a while. Most times we tend to tune out bridges. But to the early settlers and later residents of Northwest Arkansas, bridges were important. They opened up new areas of settlement, connected communities, allowed goods to be traded and marketed, and offered a safer, easier means of travel.

In order to cross a river or creek in the early days, residents established fords (low-water crossings) to walk across or drive a horse and buggy through. Enterprising individuals set up ferries, floating travelers and their wagons across a stream for a fee. Swinging footbridges were also built, but they weren’t for the faint of heart.

Passage through the hills was equally daunting. In order to go from one mountain to the next folks walked or rode up and down steep slopes, along narrow, rocky, rutted roads. It wasn’t a matter of taking the shortest, straightest path, but of following the easiest trail.

Big bridges were expensive, so whether directly or indirectly, they had to be profitable and meet a well- established need. Railroads needed them to further their business interests. Counties and states needed them for commerce and government.

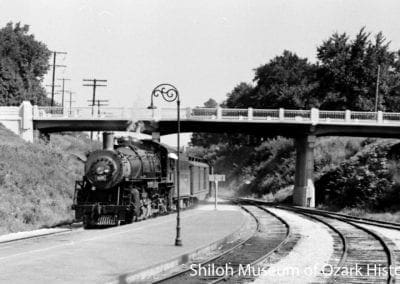

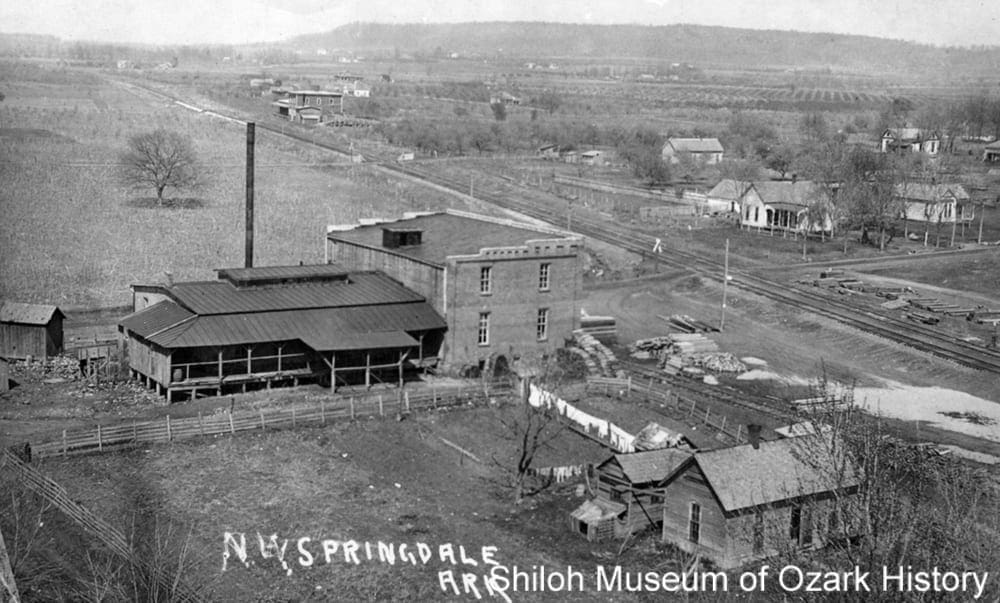

The era of big bridges came to Northwest Arkansas in the early 1880s with the coming of the railroad, which brought new opportunities for commerce. A growing economy led to a growing population. Both meant progress and progress meant bridges. The railroad helped out there as well, transporting construction materials. It would have been almost impossible to bring huge, heavy steel girders by oxcart over long distances through rugged hills.

Baptism at the White River bridge, West Fork (Washington County), about 1922. Washington County Observer Collection (S-85-111-138)

Besides the obvious aspect of travel and commerce, public safety is also a concern. Sometimes bridges fail and need to be rebuilt. Other times a new need is defined. In 2002 an overpass was built over the Kansas City Southern railroad tracks in Gravette. The project resulted from a terrible incident—a man died on the way to the emergency room when a stalled train blocked traffic.

At one time bridges played a big role in the community. Folks posed on them for photographs, stood on them to watch river baptisms, and fished from them. Bridges were used to make statements too, often with tragic consequences. In 1923 striking workers on the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA) burned eight bridges near Eureka Springs and Harrison. A striking M&NA employee was later hanged from the Crooked Creek bridge, probably in retaliation.

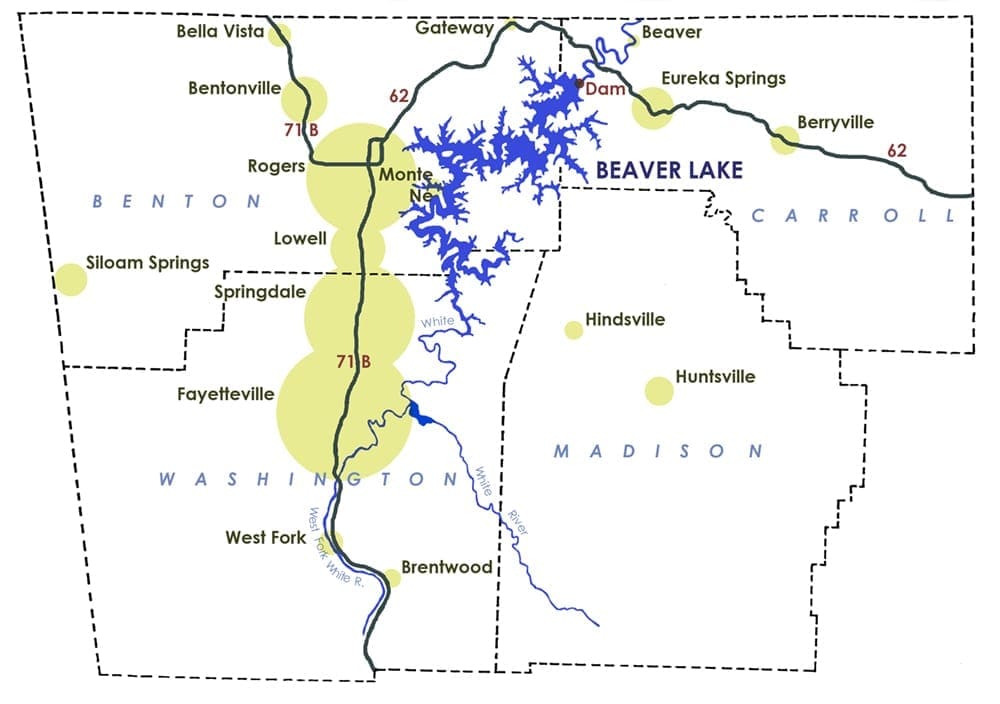

Today the bridges of Northwest Arkansas are as important as ever. New ones are being built to meet increasing transportation demands. But some of the grand old bridges are in trouble. High maintenance and restoration costs have endangered many of them including the War Eagle bridge near Rogers and the “Little Golden Gate” bridge by Beaver. So far preservation-minded folk have managed to convince officials of the need keep to them, but for how long?

In 2001 the citizens of Wyman Township near Fayetteville faced a painful decision—keep their historic bridge or replace it with a new one. Safety was a concern, as was money to preserve the old bridge. It might have been possible to build the new bridge nearby and still keep the old bridge, but it meant a longer delay in building the new structure. In the end, the bridge was torn down.

Trestle construction on the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway, Brightwater (Benton County), 1881. Robert G. Winn Collection (S-84-199-70)

When was the last time you crossed a bridge and paid attention to it? Really paid attention? It’s probably been a while. Most times we tend to tune out bridges. But to the early settlers and later residents of Northwest Arkansas, bridges were important. They opened up new areas of settlement, connected communities, allowed goods to be traded and marketed, and offered a safer, easier means of travel.

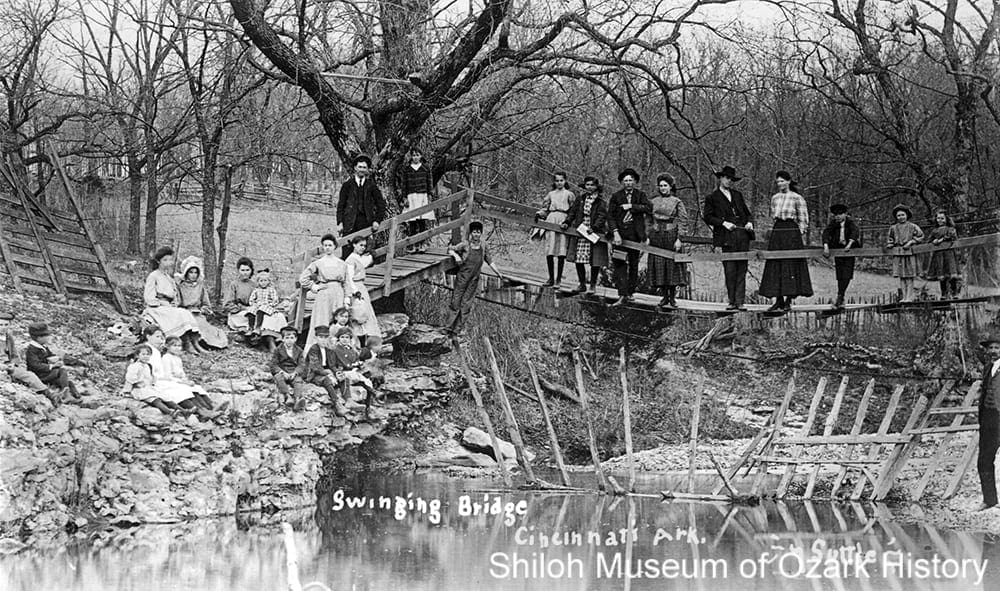

In order to cross a river or creek in the early days, residents established fords (low-water crossings) to walk across or drive a horse and buggy through. Enterprising individuals set up ferries, floating travelers and their wagons across a stream for a fee. Swinging footbridges were also built, but they weren’t for the faint of heart.

Passage through the hills was equally daunting. In order to go from one mountain to the next folks walked or rode up and down steep slopes, along narrow, rocky, rutted roads. It wasn’t a matter of taking the shortest, straightest path, but of following the easiest trail.

Big bridges were expensive, so whether directly or indirectly, they had to be profitable and meet a well- established need. Railroads needed them to further their business interests. Counties and states needed them for commerce and government.

The era of big bridges came to Northwest Arkansas in the early 1880s with the coming of the railroad, which brought new opportunities for commerce. A growing economy led to a growing population. Both meant progress and progress meant bridges. The railroad helped out there as well, transporting construction materials. It would have been almost impossible to bring huge, heavy steel girders by oxcart over long distances through rugged hills.

Baptism at the White River bridge, West Fork (Washington County), about 1922. Washington County Observer Collection (S-85-111-138)

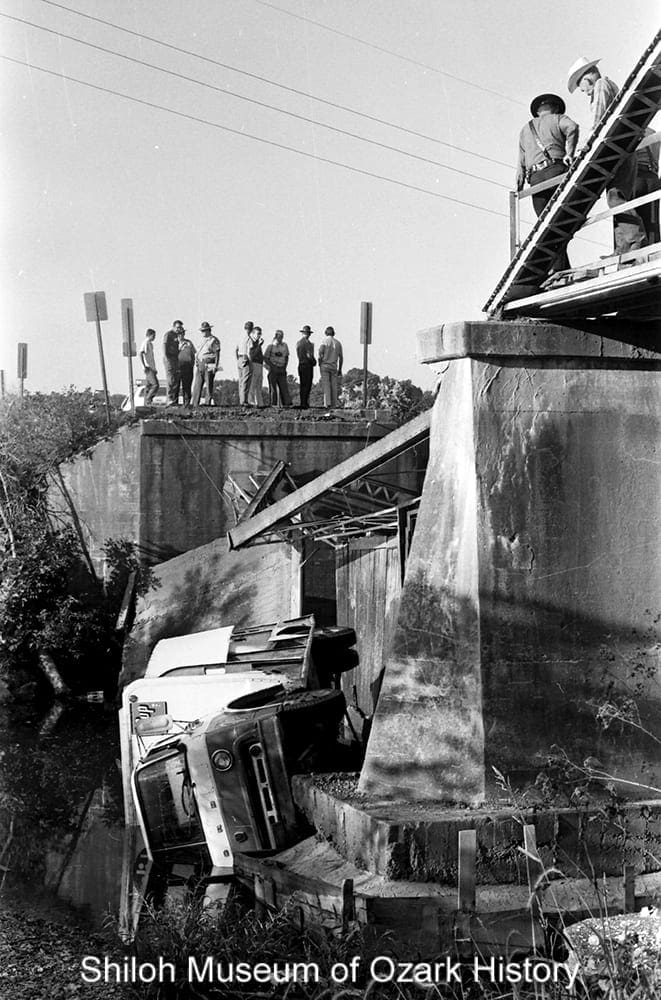

Besides the obvious aspect of travel and commerce, public safety is also a concern. Sometimes bridges fail and need to be rebuilt. Other times a new need is defined. In 2002 an overpass was built over the Kansas City Southern railroad tracks in Gravette. The project resulted from a terrible incident—a man died on the way to the emergency room when a stalled train blocked traffic.

At one time bridges played a big role in the community. Folks posed on them for photographs, stood on them to watch river baptisms, and fished from them. Bridges were used to make statements too, often with tragic consequences. In 1923 striking workers on the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA) burned eight bridges near Eureka Springs and Harrison. A striking M&NA employee was later hanged from the Crooked Creek bridge, probably in retaliation.

Today the bridges of Northwest Arkansas are as important as ever. New ones are being built to meet increasing transportation demands. But some of the grand old bridges are in trouble. High maintenance and restoration costs have endangered many of them including the War Eagle bridge near Rogers and the “Little Golden Gate” bridge by Beaver. So far preservation-minded folk have managed to convince officials of the need keep to them, but for how long?

In 2001 the citizens of Wyman Township near Fayetteville faced a painful decision—keep their historic bridge or replace it with a new one. Safety was a concern, as was money to preserve the old bridge. It might have been possible to build the new bridge nearby and still keep the old bridge, but it meant a longer delay in building the new structure. In the end, the bridge was torn down.

Bridge vs. Trestle

Jordan Creek bridge, Cane Hill (Washington County), 1930s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-208)

A BRIDGE is made up of long spans (lengths) which rest on piers and abutments (support structures in the middle of the bridge and at either end, respectively). Bridges come in many designs and materials.

Frisco Railroad trestle #1, Winslow (Washington County), 1900s. Mary Lucille Lewis Yoe Collection (S-2002-51-16)

A TRESTLE is made up of short spans supported by splayed vertical elements also known as trestles (individual rigid frames). Railroads often built trestles in mountainous areas and in floodplains as part of the approaches (access points) to a bridge over a river.

Types of Bridges

The choice of bridge is determined by many factors including length of span, available materials, cost, geographical terrain, geology, available work force, and weight needs. Truss bridges are made up of small pieces that are easily transported and put into place. They are very economical to build because they make efficient use of materials.

Suspension bridges make long spans possible. They can be as simple as ropes and wood planks hanging over a creek or as elaborate as a concrete and steel cable structure spanning a wide river. Concrete girder bridges are the most common bridges built today in Northwest Arkansas.

Arch bridge, Highway 16, White River, Fayetteville (Washington County), 1940s. Marion E. Brown Collection (S-95-161-15)

An ARCH BRIDGE has one or more arches as the main support and abutments at either end. It is one of the oldest types of bridges.

Girder bridge, Highway 68, Osage Creek (Carroll County), 1950s–1960s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-112)

A GIRDER BRIDGE has long horizontal beams placed on abutments and piers. The roadway deck is built on top of the girders.

Types of Trusses

A TRUSS is a rigid framework structure made of metal bars or wood beams which provides support.

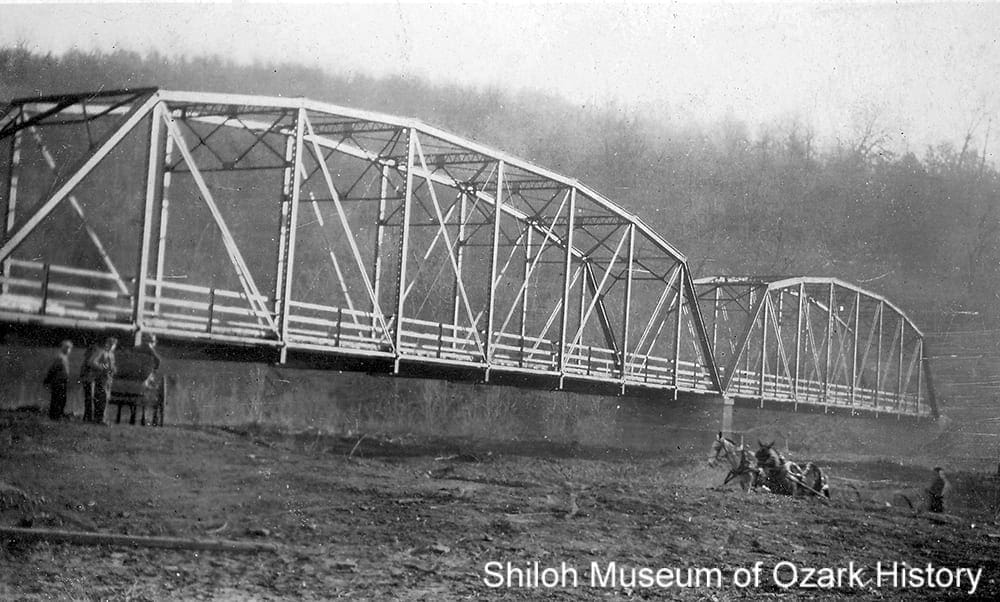

Parker through-truss bridge, White River, Woolsey (Washington County), May 22, 1935. Bertha Reed Collection (S-93-125-6)

A THROUGH-TRUSS BRIDGE has framework above and below the deck and is cross-braced at the top.

There were two common through-truss bridges in the Ozarks. A PRATT TRUSS BRIDGE has diagonal members which form a “V” shape. The members slant down and towards the center, except for the members on the ends. The truss has a flat top.

A PARKER TRUSS BRIDGE is a modified Pratt truss. The top part of the structure is somewhat curved.

Photo Gallery

Railroad Trestles and Bridges

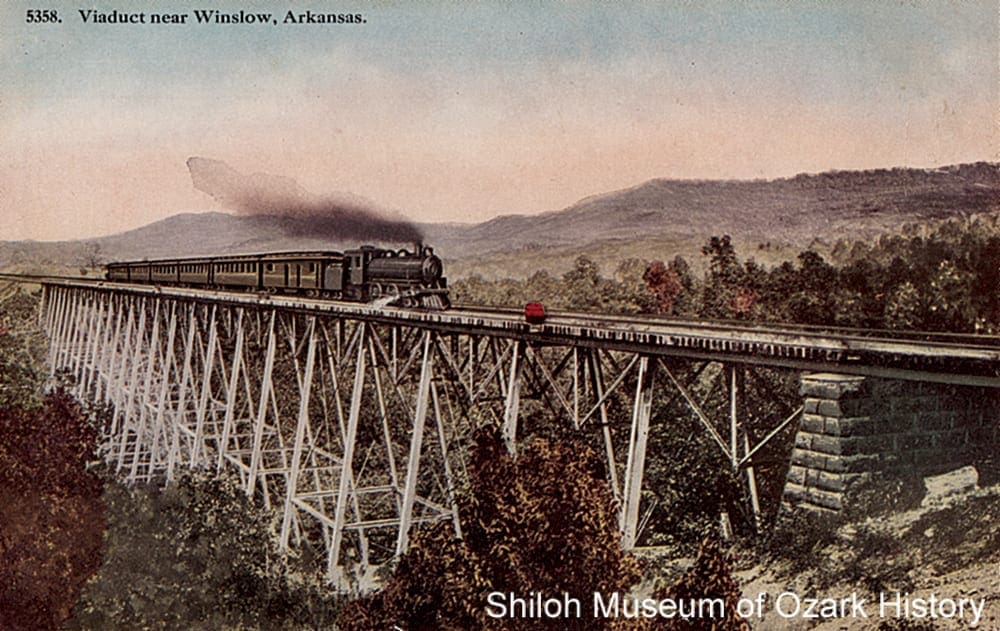

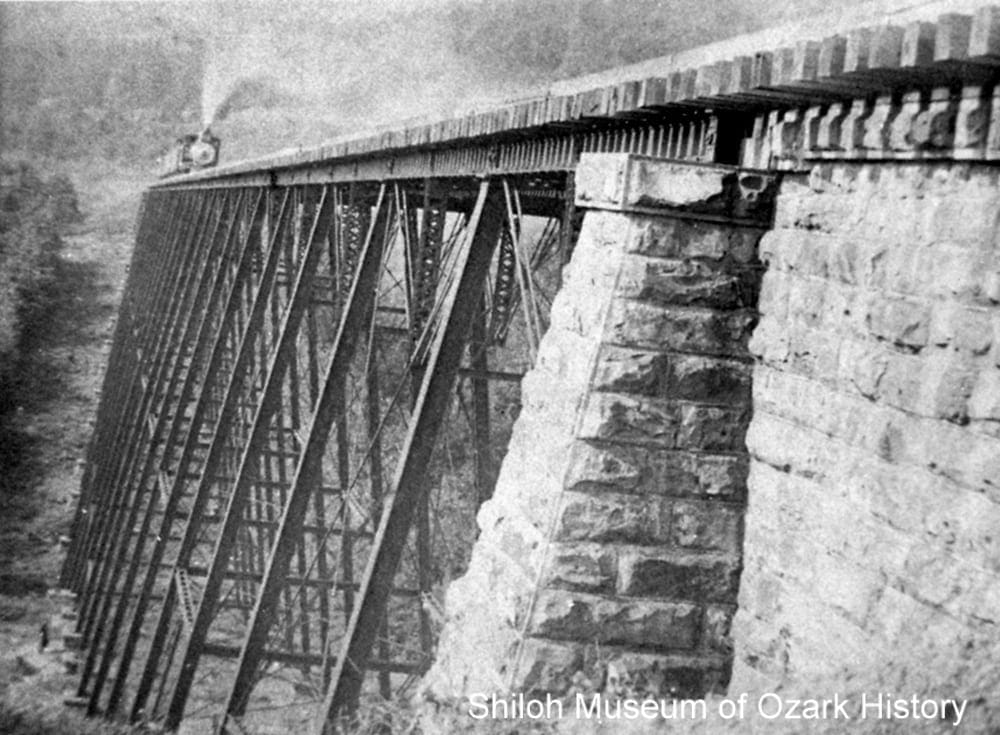

Frisco Railroad trestle #1, Winslow (Washington County), about 1900. John D. Little Collection (S-92-109-42)

The St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad (the “Frisco”) came to Northwest Arkansas in 1881. The Delaware Bridge Company built three trestles for the railroad near Winslow, including the longest one, #1, in 1882. That trestle is 780-feet long and, at its highest, rises 115 feet over the valley floor. The original iron trestle was replaced with a steel trestle in 1907. Deck plate girders were added to allow heavier steam engines and longer freight trains. The trestle is still in use by the Arkansas & Missouri Railroad. Passengers on the railroad’s excursion train to Van Buren have a bird’s-eye view of the rugged, spectacular valley.

Kansas City & Memphis Railway trestle, Elm Springs (Washington County), March 1911. Marion Mason Collection (S-2001-70-17)

The cut timber and peeled-log trestle at Elm Springs was built in 1911 over a wide floodplain bordered by hills. At 1,116 feet in length, it was probably the longest trestle in Northwest Arkansas. The railroad faced financial difficulties because its main line paralleled that of its rival, the Frisco. There wasn’t enough business. In 1918 the railroad ceased operation. During World War I the steel track was removed for the war effort. The trestles were likely left in place.

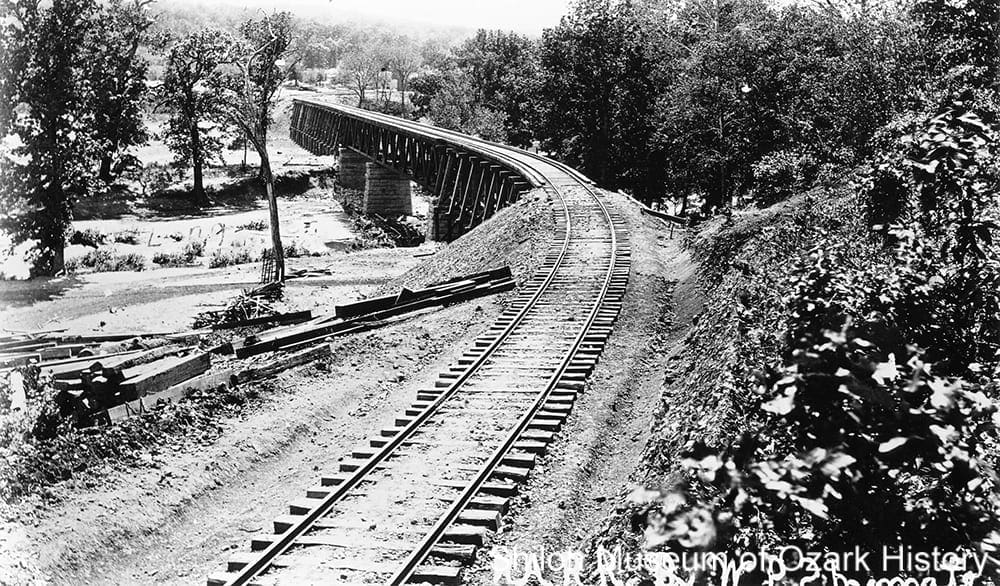

Engine #3 pushing a lumber car during the construction of the St. Louis & North Arkansas Railroad bridge, Kings River, Grandview (Carroll County), 1901. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-87)

This deck truss bridge with trestle approaches was built in 1900–1901 by the Wisconsin Bridge & Iron Company, builders of many steel bridges in Northwest Arkansas. In February 1901 it was reported that about two miles of track were being laid every day. This railroad line changed hands several times, eventually becoming the Arkansas & Ozarks Railway before being abandoned in 1961.

St. Louis & North Arkansas Railroad bridge, Long Creek, Alpena (Boone County), 1901. W. P. Shumate, photographer. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-92)

The Wisconsin Bridge & Iron Company built this deck truss bridge with trestle approaches in 1900–1901. The steel members for the bridge were brought from Eureka Springs by wagon. A Swede by the name of Ole Loken was the supervisor for both the Long Creek and Kings River bridges. He was especially proud of their handsome deck truss spans. The bridge was situated in the middle of an S-curve making for a picturesque scene for travelers. A large portion of the trestle was burned in 1920 by striking railroad workers. Financial difficulties caused by a bridge collapse and the switch to transporting goods by truck led to the abandonment of the railroad in 1961.

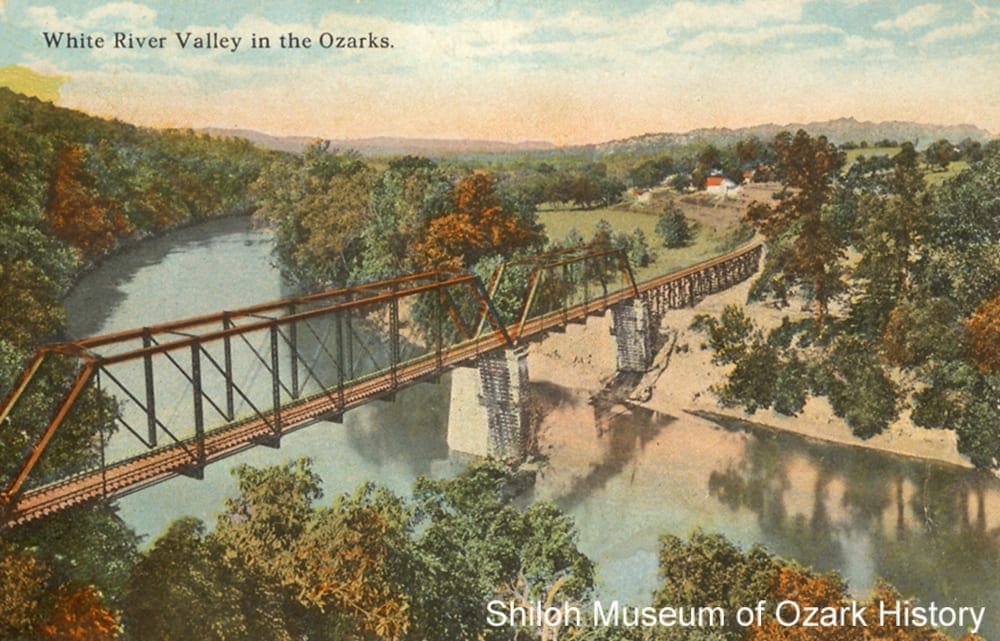

Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad bridge, White River, Beaver (Carroll County), circa 1910. Frank O’Donnel Collection (S-83-157-44)

When the bridge was first built in 1882–1883 for the Eureka Springs Railway, it was able to support the standard axle loading of the day (the weight supported by each axle). Later locomotives and cars were heavier. As it was impractical to strengthen the existing bridge, the Wisconsin Bridge & Iron Company built a new, heavier bridge and moved the spans into place in 1907. The bridge and the deep cut through a limestone bluff just beyond it, known as “The Narrows,” was a popular excursion trip for tourists staying in Eureka Springs. On the Fourth of July fireworks were shot off the bluff. Planks placed between the rails of the bridge allowed visitors to walk across it to a rocky beach or to the little town of Beaver. Today the bridge is abandoned. The steel spans are still in place, but the decking and approaches are gone.

Road Bridges

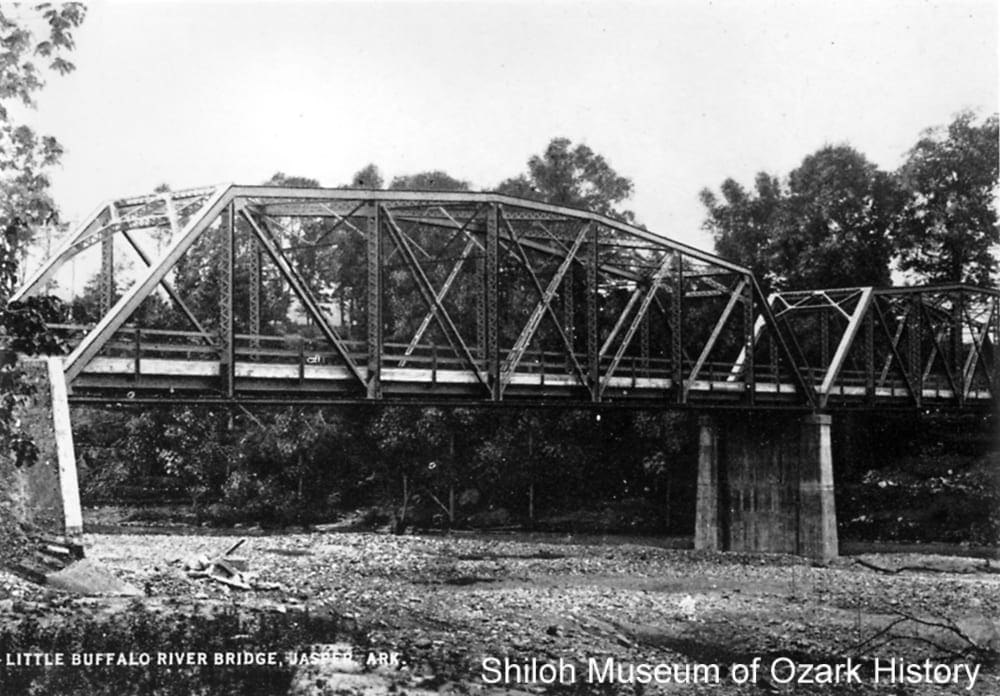

Arkansas Highway 7 bridge, Little Buffalo River, Jasper (Newton County), circa 1925. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-213-12)

The bridge over the Little Buffalo River was built in 1924-1925. The two-span, Parker through-truss bridge was replaced in 1974.

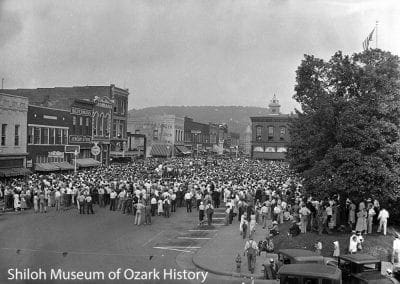

War Eagle Craft Fair visitors, War Eagle (Benton County), October 16, 1987. Springdale News Collection (SN 10-16-1987)

Several small fords used to cross the War Eagle Creek in the 1800s, but floods washed them out, preventing area residents from traveling to town. In 1907 about 100 residents signed a petition asking for a permanent bridge. Construction began later that year on the $4,790, Parker through-truss bridge built by the Illinois Steel Bridge Company.

As the 304-feet long bridge aged, structural problems developed and maintenance costs grew. At one time there was talk of replacing it, but concerned citizens argued for its preservation. After several months of work, in October 2017 the bridge reopened, ahead of schedule and under its $1.4 million budget. The bridge was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

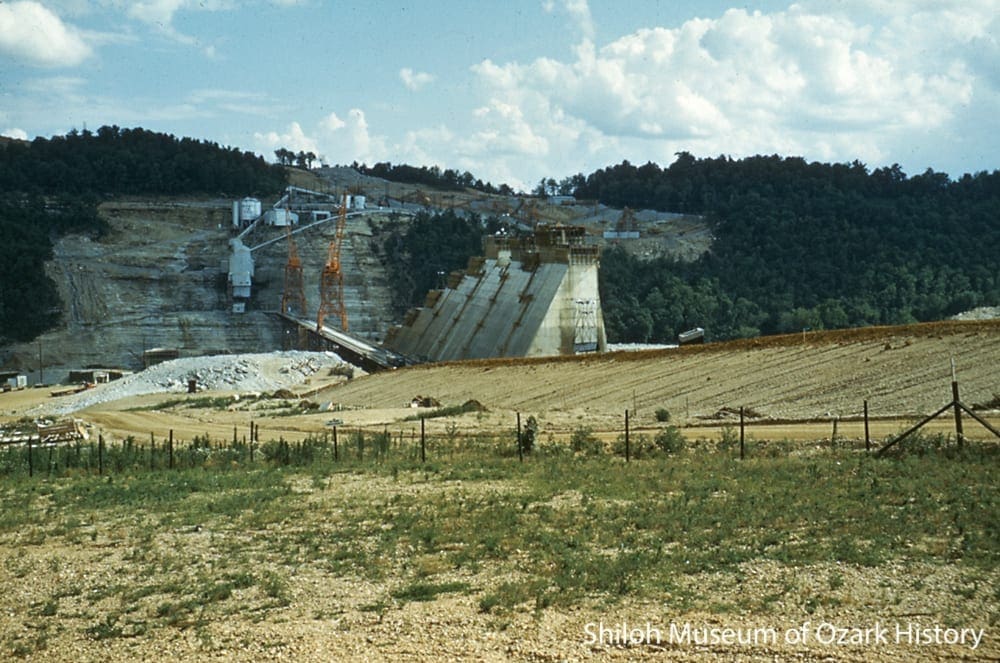

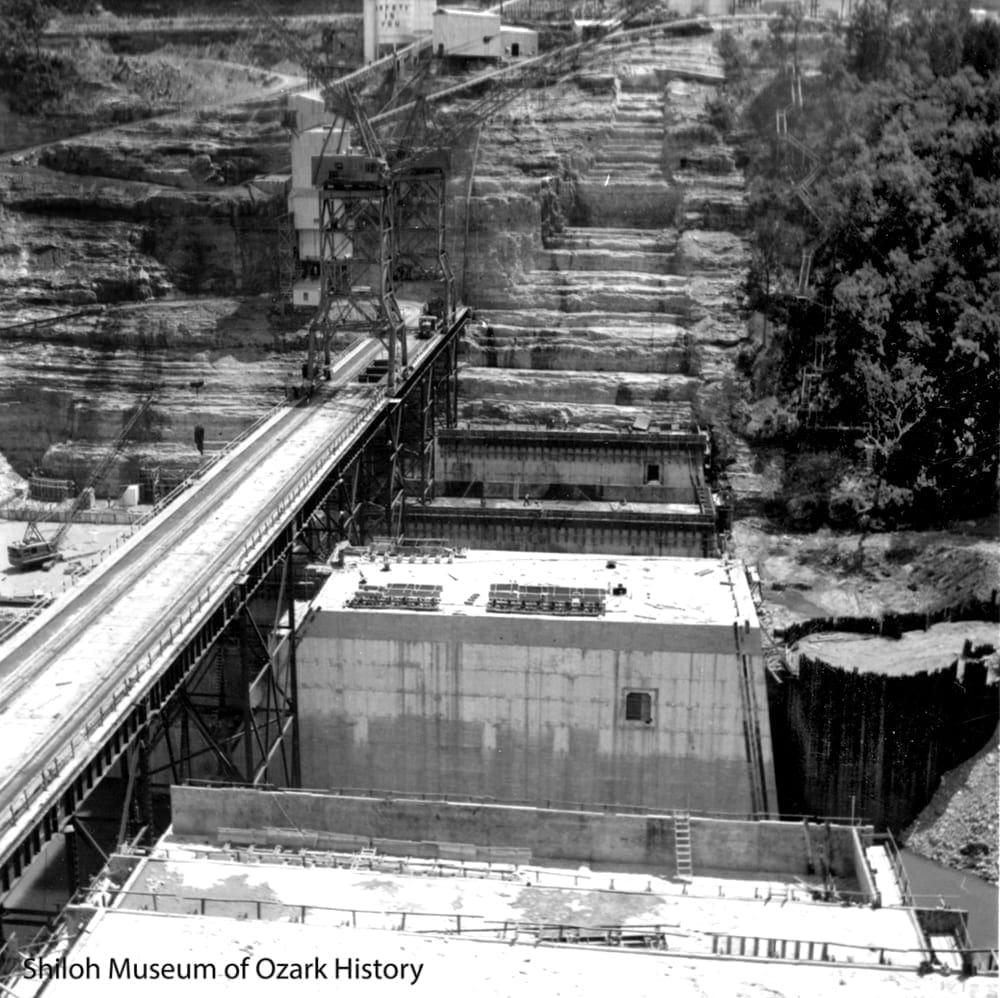

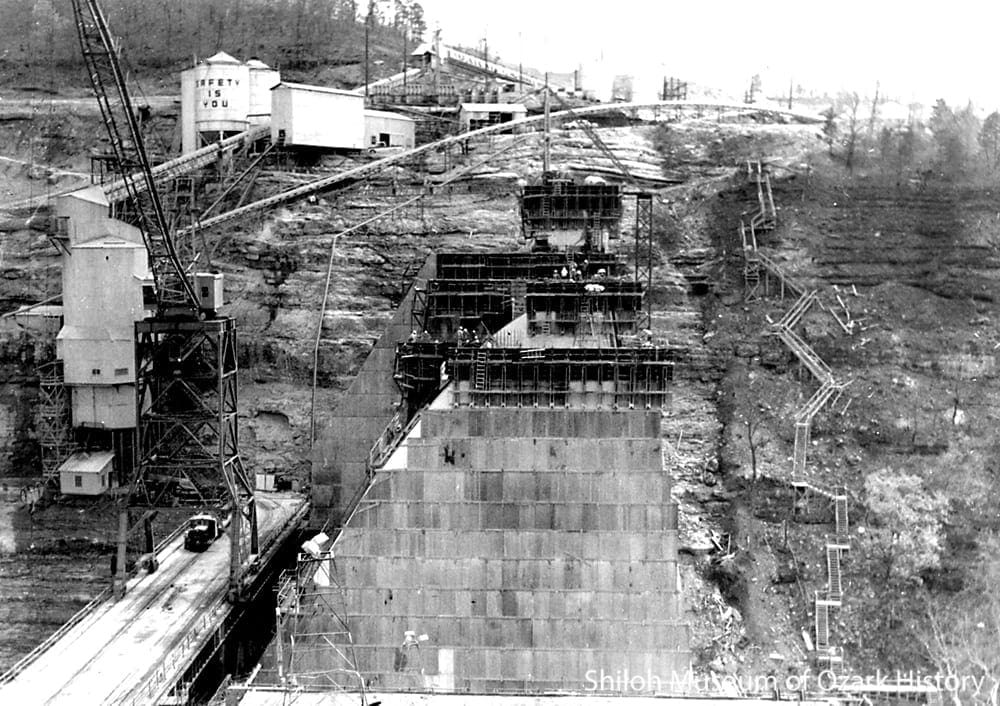

In 1904 a steel Parker through-truss bridge was built east of Rogers over the White River. It became obsolete during the construction of Beaver Lake.

The old bridge was torn down in 1963 as its replacement was on the rise nearby. When area residents were told the new concrete girder bridge would span from one hill to the next, they couldn’t believe it. It was hard to imagine a huge lake in their valley. Folks traveled to the construction site to take photos and home movies.

In 2008 travelers saw water lapping just below the deck of the bridge as record rains flooded the lake.

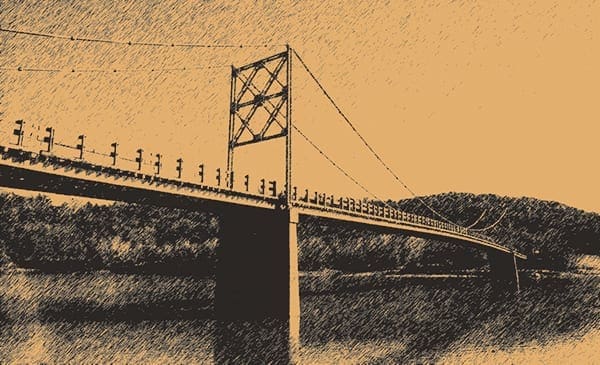

“Little Golden Gate” bridge, White River, Beaver (Carroll County), November 6, 1994. Scott Flanagin, photographer. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT 11-6-1994)

The wire suspension bridge at Beaver is one of a handful of such bridges left in Arkansas. It was built in 1949 by the Pioneer Construction Company of Malvern for $107,785. It replaced a concrete bridge that washed out in the early 1940s.

Although it has a weight limit, this single-lane, 554-feet long bridge is still in use. Because of the bridge’s arch, drivers can’t see if a car is coming from the opposite side. When two cars meet the one furthest along has the right-of-way; the other car must back up. The rippling motion of the bridge can be unnerving.

This picturesque bridge is a favorite of automotive and motorcycle clubs and was seen in the 2005 film Elizabethtown. At one time scheduled for demolition, the bridge is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Lafayette Street bridge (with Maple Street bridge in background), Fayetteville (Washington County), circa 1909. Speece & Aaron, photographers. Mrs. Kenneth Tillotson Collection (S-90-91-1)

A bridge was first built in this location just north of the Frisco depot in 1884. It was later replaced by another wood bridge before a $30,000 Art Deco-style concrete bridge was built in 1938.

Bridge construction, War Eagle Creek, Withrow Springs (Madison County), 1914. May Markley Reed Collection (S-84-155-63)

This 280-feet long steel Pratt through-truss bridge was the first big bridge in Madison County. It was built 1914–1915 by the Leavenworth Bridge Company of Kansas for $6,462. P. B. Reed of Huntsville, builder of the swinging bridge at Marble, served as construction foreman.

The bridge was paid for in part by a one mill tax levied on county residents. Citizens near the new structure also contributed $700, a portion of which was used to build the approaches. The bridge is still in use as part of Highway 23, but in need of costly repairs.

Bridge construction, Osage Creek, Berryville (Carroll County), 1901. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-86-211-9)

Some of the equipment used to build this two-span, Pratt through-truss bridge can be seen, including a winch and the rigging used to raise the metal supports. The piers which hold up the deck are poured concrete. The pier on the farther edge of the creek bed appears broken and unused.

The bridge collapsed in March 1999, causing a man in a pickup truck to plunge into the creek. Prior to his crossing, a concrete truck that was too heavy for the posted weight limit on the bridge had traveled across it, likely weakening the bridge.

Tilly Willy bridge, West Fork of the White River, near Fayetteville (Washington County), 1980s. Joe Neal, photographer. Joe Neal Collection (S-88-247-35)

Although used as a bridge, the structure was built in 1928 as the fourth dam in Fayetteville’s Water Improvement District #1. Over a period of about 20 years a series of dams were built along the White River to impound water for the growing city of Fayetteville, during a time when the area was facing drought. In 1930 a fifth and final dam was built, creating Lake Wilson.

Tilly Willy may owe its interesting name to Matilda Wilson who lived in the area and likely had a ford named after her. The 160-feet long concrete and rock bridge was replaced in 2012.

Bridge construction at Lake Wedington (Washington County), circa 1937. C. B. Wiggans, photographer. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-91-74-66)

The rock and mortar bridge was built around 1937 by members of the Civilian Conservation Corps under the direction of C.B. Wiggans of Fayetteville, project manager. While some mechanized equipment was used to build park structures, most of the work was accomplished with the use of mule teams, pickaxes, and shovels. The construction materials came from the land itself.

Lake Wedington was built by the Works Progress Administration to show farmers how their worn-out or eroded fields could be developed for beneficial use. The project also offered much-needed jobs to an area suffering the financial woes of the Great Depression. Salaries ranged from twenty-five to fifty cents an hour for a ten-hour day.

White River bridge, Highway 68 (now Highway 412), near Sonora (Washington County), circa 1961. Vince Little Collection (S-2001-57)

The 617-feet long steel and concrete girder bridge was built in 1961 by the E. E. Barber Construction Company of Fort Smith. It replaced an old through-truss bridge that was considered inadequate by 1945. Nearby Springdale was a growing town and there was too much traffic for a one-lane bridge built for horse-drawn wagons.

In the late 1940s the roads on either side of the White River were finally paved, but the Korean War and other difficulties kept the bridge from being built. When construction finally began, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers helped with building costs since the waters of Beaver Lake, then under development, would back up in the White River and cover nearby property.

Sometime around the turn of the 21st century the bridge was blown up, following the construction of two double-lane replacement bridges further north.

Twin Bridge #1, Baron Creek Ford, near Morrow (Washington County), 1970s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4755)

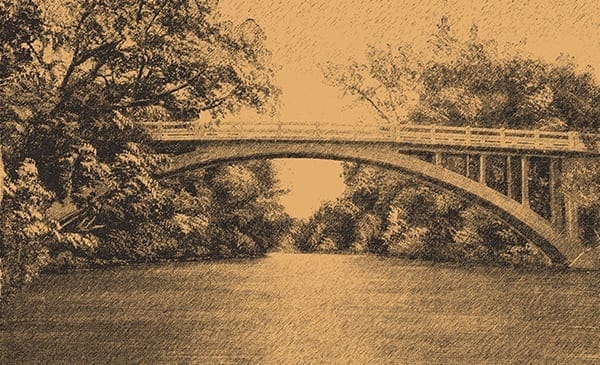

In 1922 the Luten Bridge Company of Tennessee built this concrete arch bridge located on Washington County Road #3412. The company’s founder, Daniel B. Luten, was a civil engineer who specialized in reinforced concrete bridges, patenting a number of innovations and designs. For many years his company held a monopoly on such bridges.

Twin Bridge #2 is smaller and located a few hundred feet away. Both bridges are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Foot Bridges

Swinging footbridge, Kings River, Marble (Madison County), about 1915. William H. Chenault Collection (S-2005-37-39)

The 3-feet wide, 200-feet long cable footbridge was built by P. B. Reed of Huntsville. The contract stated that the bridge would be no more than 15 feet above the low-water level of the river. The builder provided all materials except the rock needed for the foundation and anchors. The cables used for the bridge were three-quarter inch in diameter. Turnbuckles allowed the cables to be tightened so that the sag was no more than five-and-one-half feet overall. A sign on the bridge states, “Five dollar fine for any one to add any extra strain on bridge.”

Swinging footbridge, Cincinnati Creek, Cincinnati (Washington County), May 16, 1909. Suttle, photographer. Ruth Ann Wilson Collection (S-83-324-41)

Before the footbridge was built, folks had to cross the creek by foot. G. W. Bond remembered a time in his youth when he spied Brother Hanks removing his shoes and socks and rolling up his pant legs to ford the cold waters of the creek. Definitely not a dignified look for a preacher!

Credits

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. “Illinois River Bridge at Phillips Ford, Savoy Vic., Washington County.”

Benton County Daily Democrat. “War Eagle Bridge Protected.”12-17-1985.

Benton County Pioneer. “The ‘Gravette Overpass.’” Vol. 47, No. 3 (2002).

Branham, Chris. “Venerable Victory.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 4-16-2006.

Bridges and Tunnels of Alleghany County and Pittsburgh, PA. “Bridge Basics.”

Brotherton, Velda. “Bridging Streams and Rivers Once Only for the Adventurous at Heart.” Washington County Observer, 3-18-1999.

Dempsy, David Frank. “Little Golden Gate Bridge is Unique Crossing.” Carroll County News, March 1996.

Fair, James R. Jr. The North Arkansas Line: The Story of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroads. Howell-North Books, 1969.

Harrison News. “Local News” [SL&NA bridge at Grandview]. 1-26-1901.

———. “Local News” [SL&NA track laying], 2-29-1901.

“Historic Bridges of the United States.” BridgeHunter.com

Huntsville Republican. “Madison County’s First Bridge.” 2-4-1915.

Hutcheson, Harold. “The Frisco Bridge Gang.” Washington County Observer, 12-8-1983.

Jones, Herman. Interview with Shiloh Museum staff regarding the Tilly Willy bridge, Fayetteville, April 2009.

Kelly, Leonard. Interview with Shiloh Museum staff regarding the Tilly Willy bridge, Fayetteville, April 2009.

Madison County Record. “Old War Eagle Bridge 1925.” 9-28-2000.

Matsuo Bridge Company, Ltd. “The Basic Bridge Types.” 1999.

Patton, Susannah. “The Legend of the Tilly Willy.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 11-25-2007.

Rogers Historical Museum. White River: A Valley and its People exhibit publication. 2000.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. Land, Labor, Legacy: The History of Lake Wedington exhibit outline. 1996.

Sissom, Tom. “War Eagle Bridge opens ahead of schedule.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 9-21-2017.

Trent, Sandra. “Wyman Residents Vote to Destroy Historic Bridge.” White River Valley News, 10-18-2001.

Wilson, Jaunita. History of Cincinnati, Arkansas. 1986.

Winn, Robert G. “Tilly Willy Bridge.” Washington County Observer, 3-17-1983.

———. Railroads of Northwest Arkansas. Washington County (Arkansas) Historical Society, 1986.

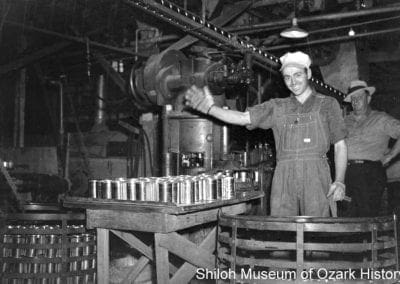

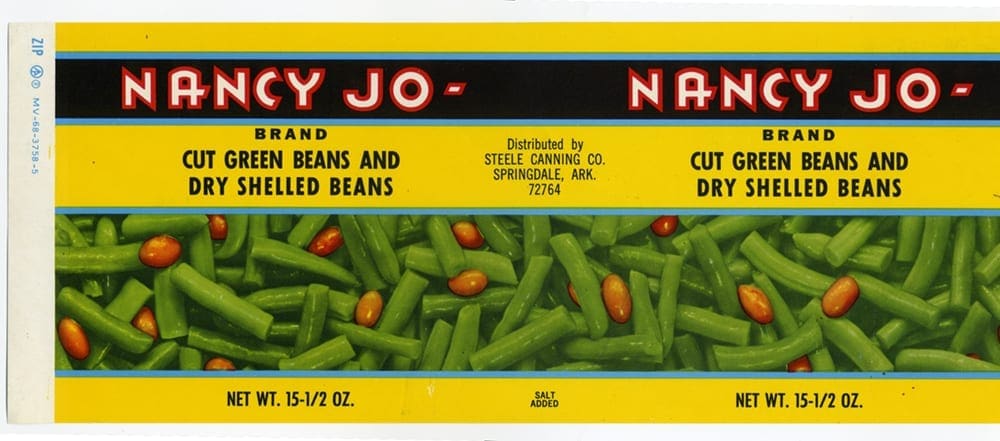

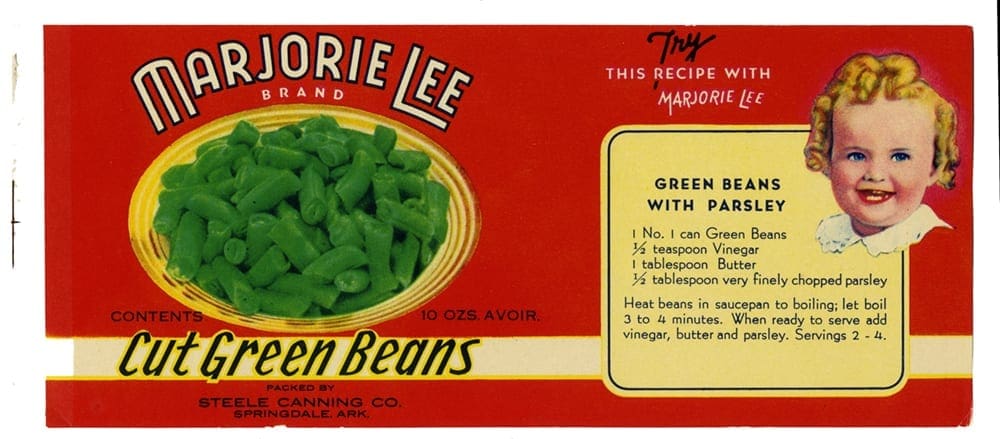

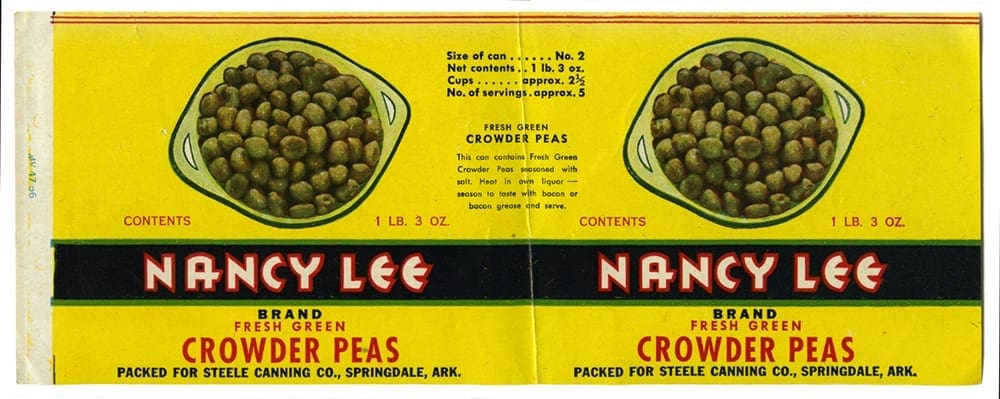

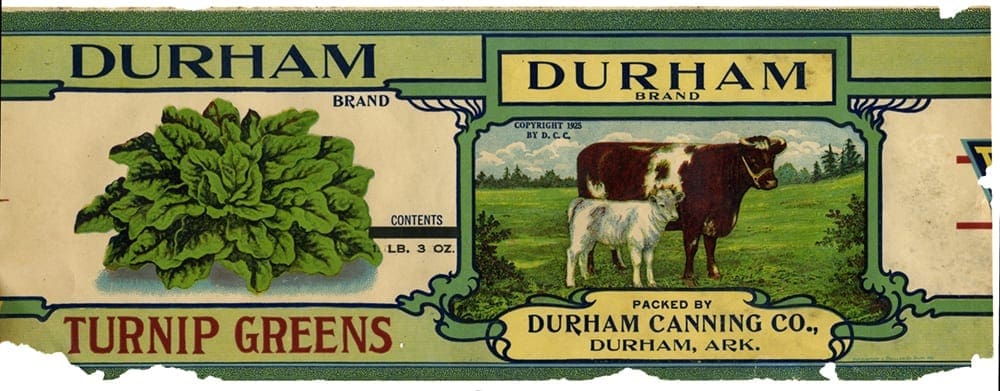

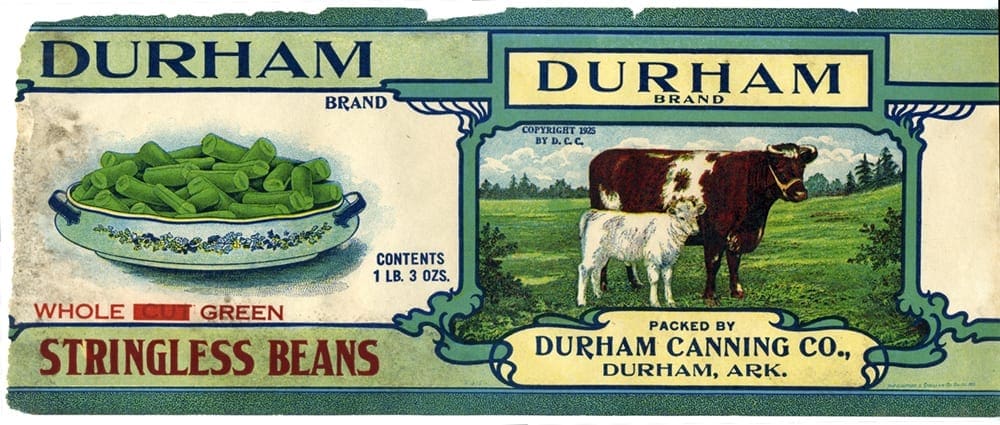

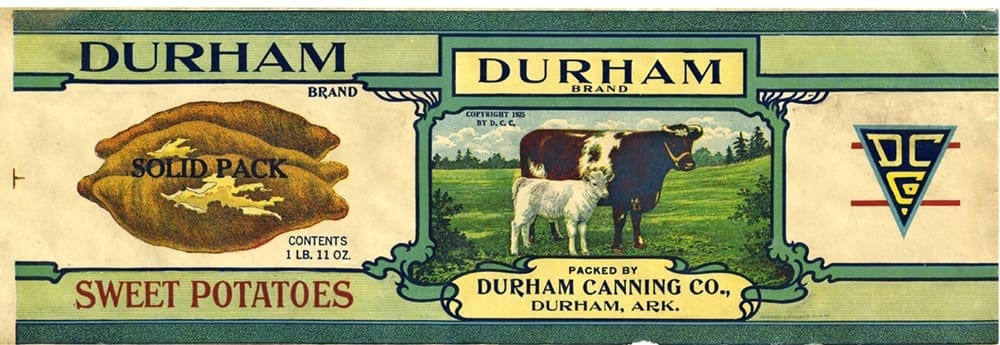

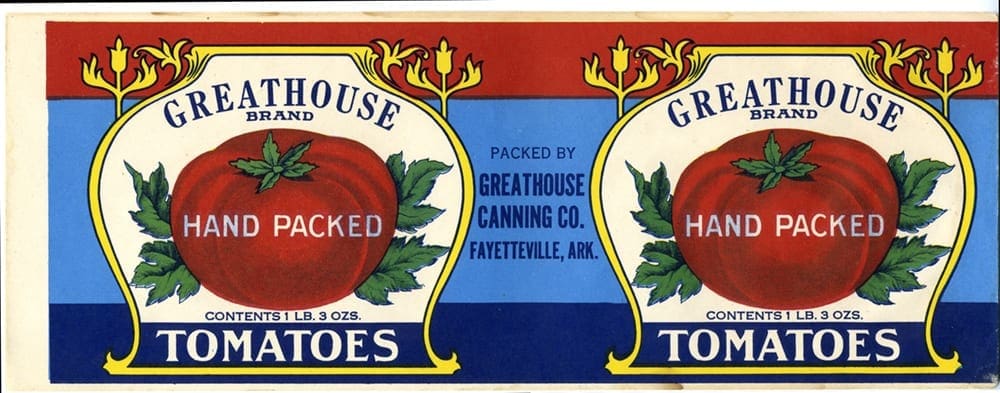

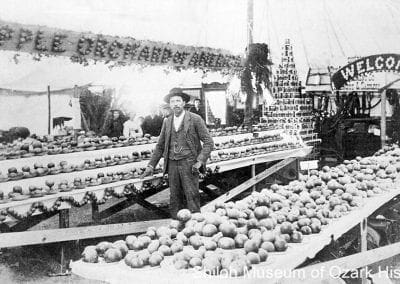

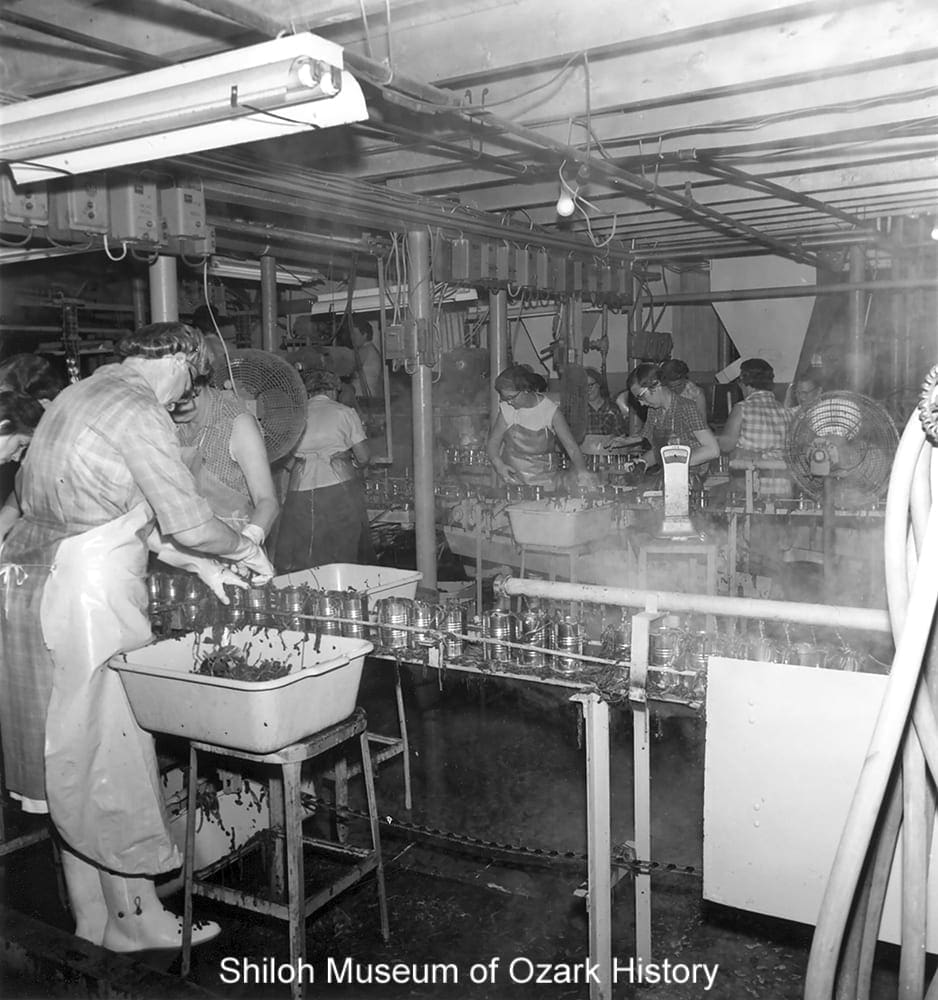

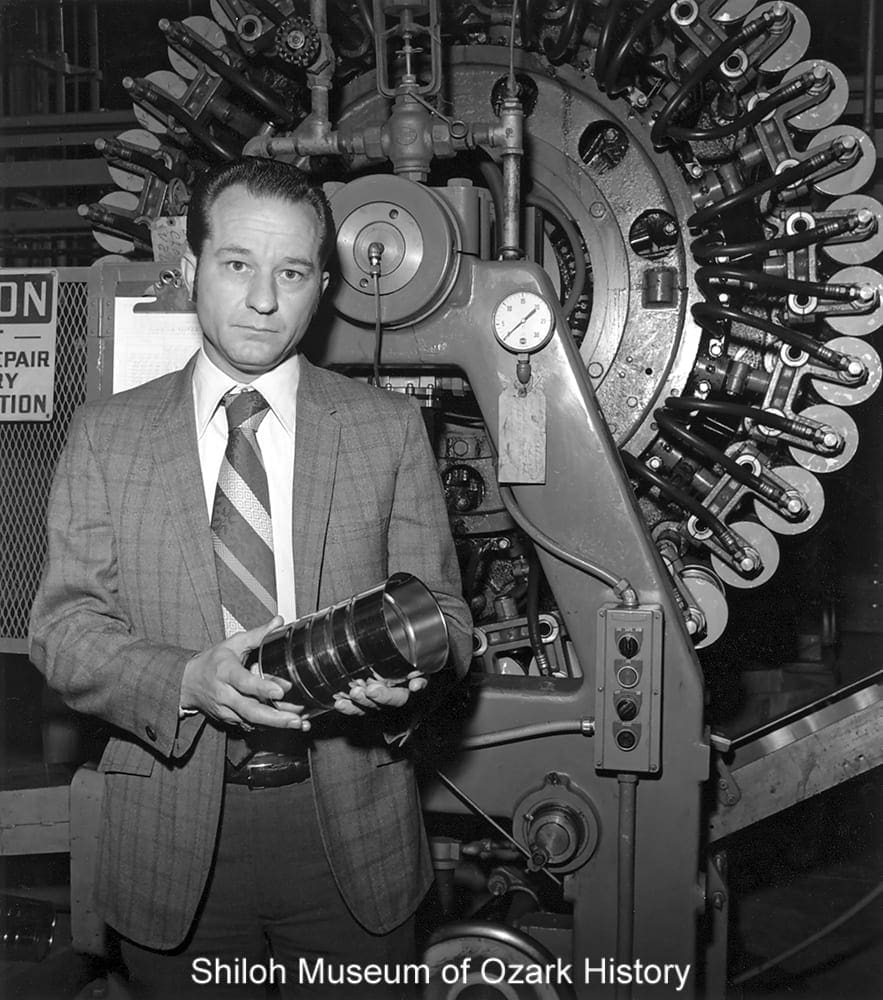

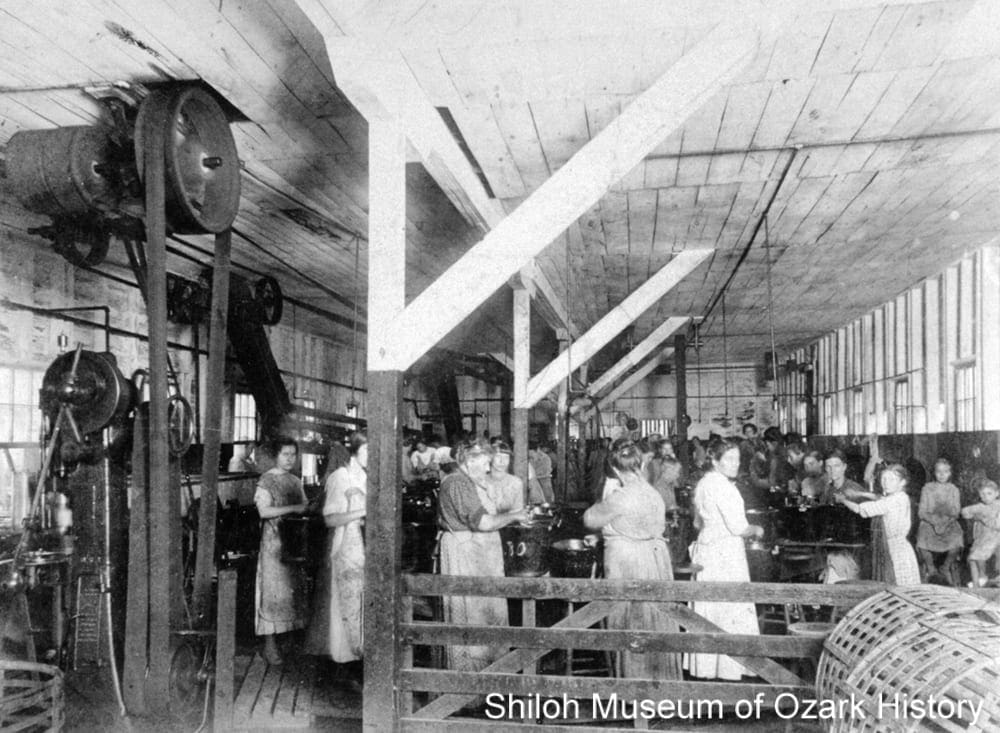

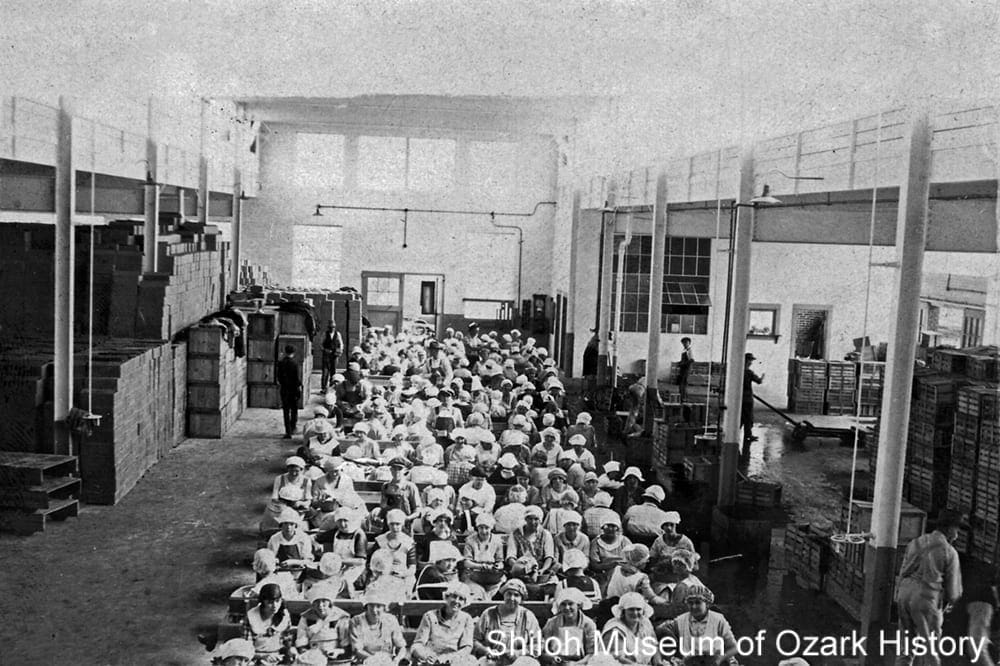

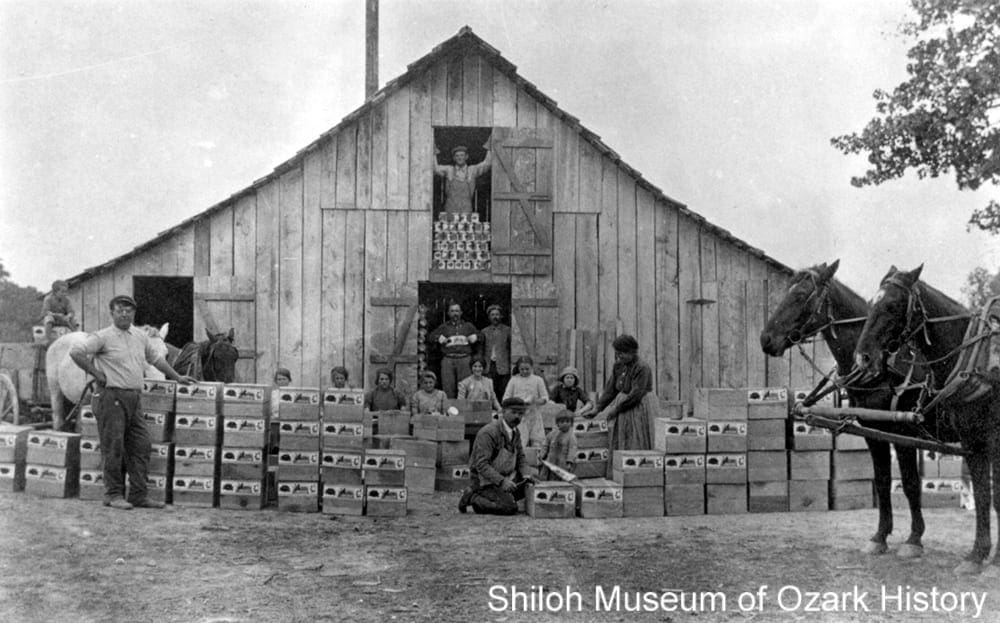

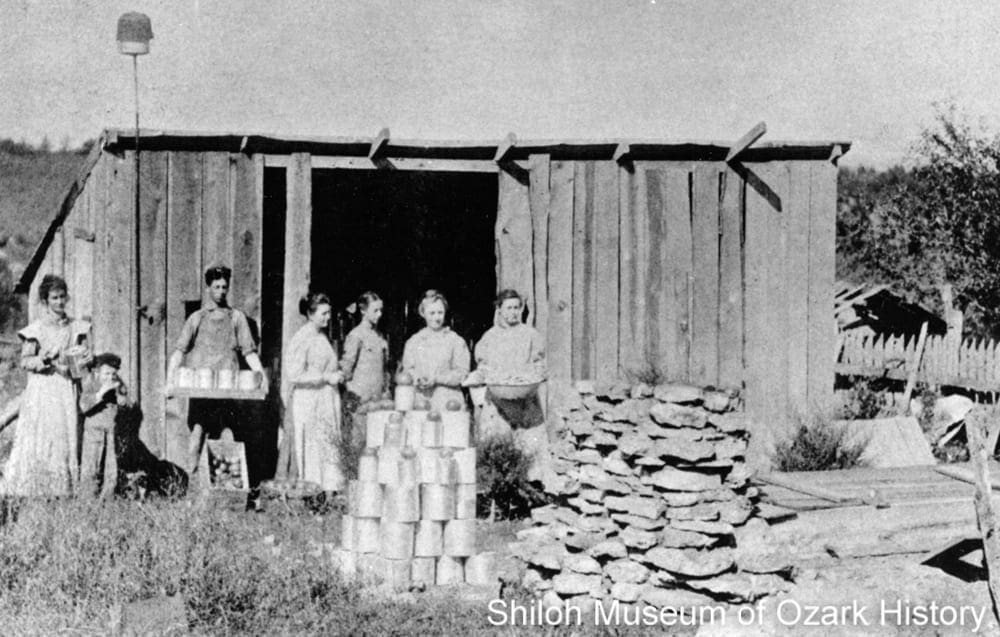

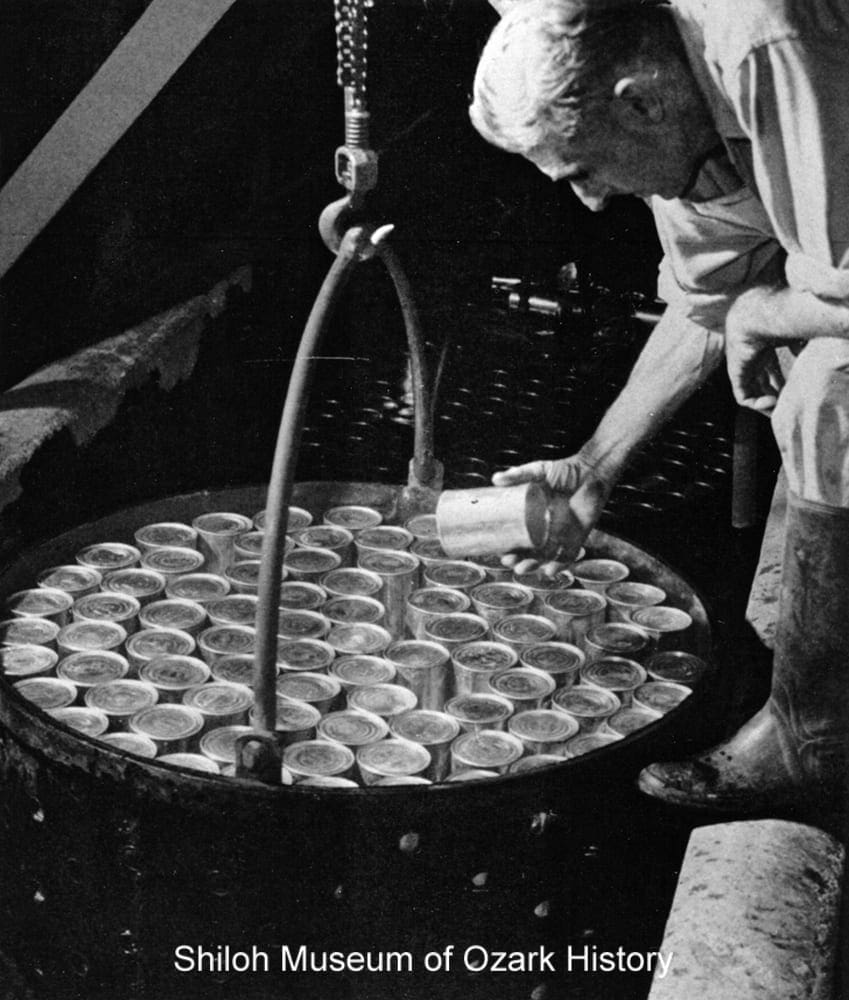

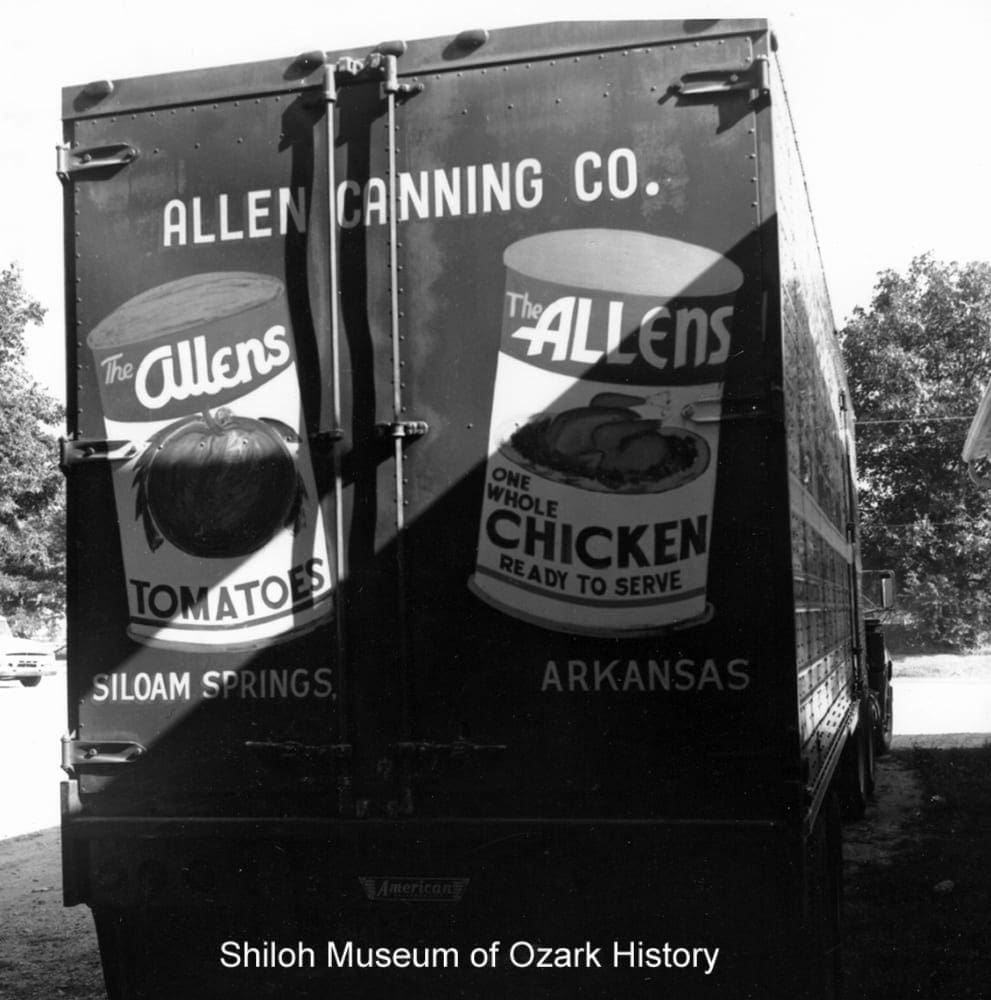

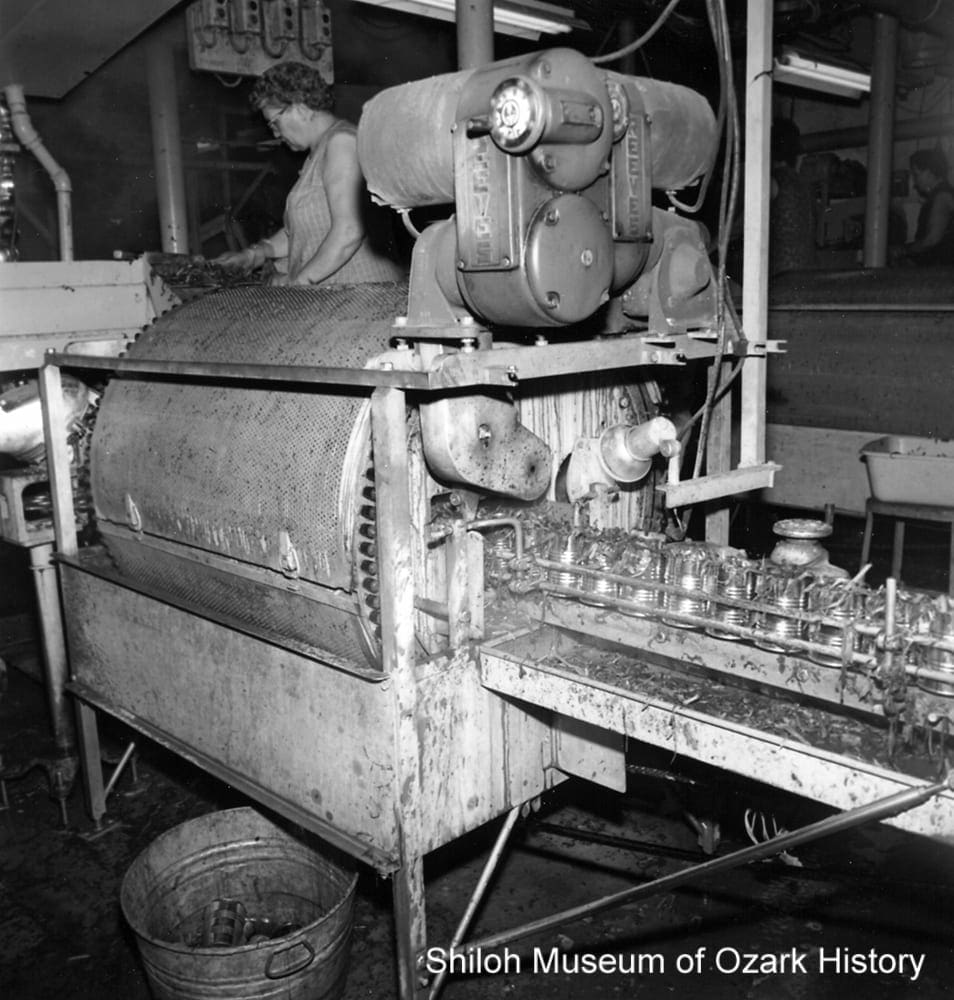

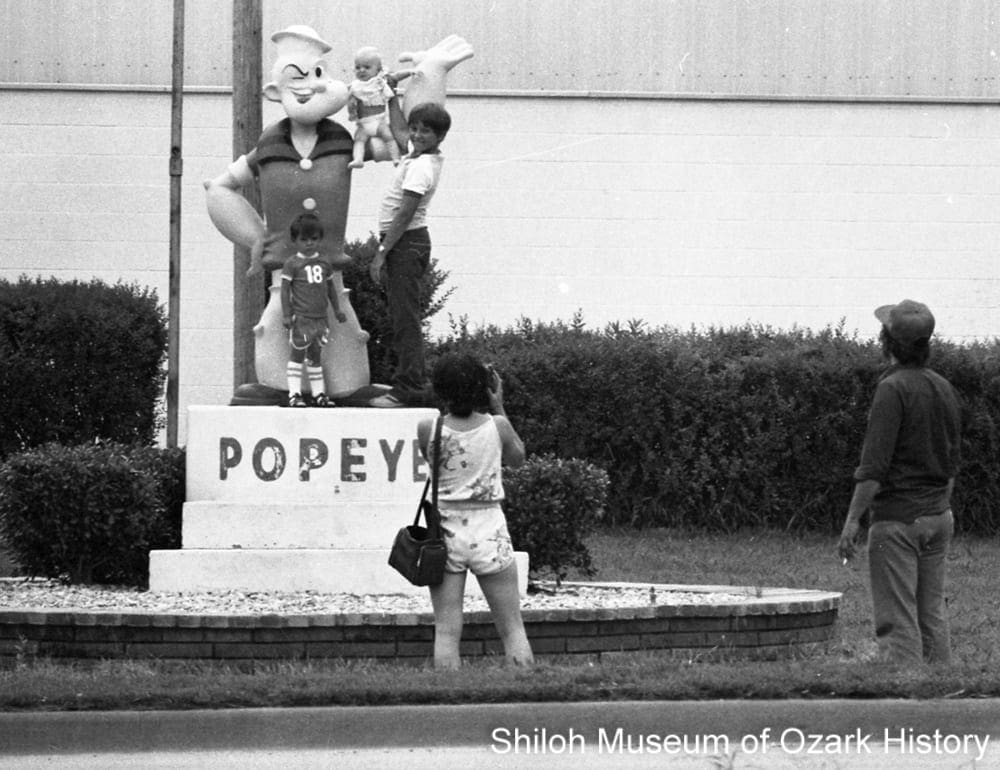

Hey, kids! I’m Snappy, a green bean grown on a farm right here in Northwest Arkansas. Did you know that during World War II the Springdale Canning Company packed 12,000 cases of green beans each summer day? That’s a lot of beans! Come with me on a tour of the process from start to finish.

Hey, kids! I’m Snappy, a green bean grown on a farm right here in Northwest Arkansas. Did you know that during World War II the Springdale Canning Company packed 12,000 cases of green beans each summer day? That’s a lot of beans! Come with me on a tour of the process from start to finish.