Bumper Crop

Online Exhibit

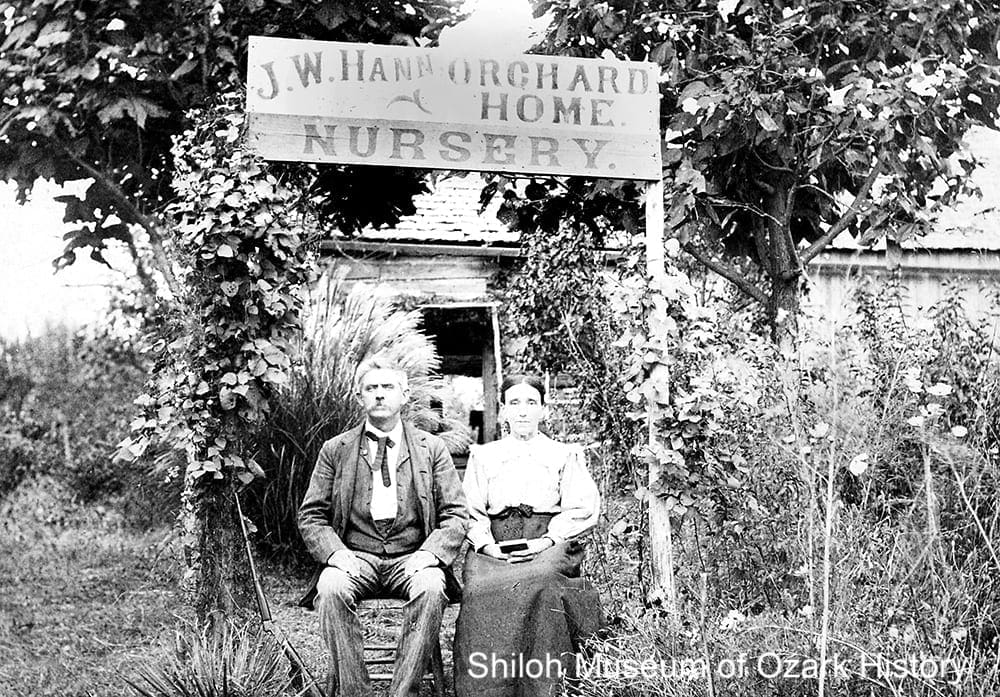

John and Martha Hann, Friendship Community southwest of West Fork, about 1908. Elsie Cress Young Collection (S-85-129-32)

About Apples

Johnny Appleseed’s mission of planting apple seeds wasn’t about growing apples for pies, but for cider making. That’s because apple seeds don’t grow true. A seed from a Granny Smith apple doesn’t grow into a tree bearing Granny Smiths.

Apples grown from seed are often bitter or sour. But every now and then a seed grows into a tree which produces a flavorful apple. In order to replicate the fruit, a scion (prepared twig) from the desired tree is grafted onto a sturdy rootstock. That is, the plant tissue from one tree is “fused” into the plant tissue of another tree. The resulting tree is a clone of the parent tree. Trees grown from seed are considered “seedling varieties.” Trees grown from grafts are considered “propagated varieties.”

During the 1700s and 1800s most people in the U.S. drank apples, rather than ate them. They turned their apple crop into cider (what we now call hard cider) a more popular drink than water, wine, beer, or coffee. A mildly alcoholic beverage, cider was easier and safer to make than corn liquor. Apple juice could also be distilled into high-proof apple brandy and applejack. In Northwest Arkansas folks probably made cider at home, but there isn’t evidence of commercial cider mills like there were in the East or Midwest. It may be that folks better trusted the water in the Ozarks.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that apples were primarily considered a food crop. Around the turn of the 20th century groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union began fighting alcohol and the evils associated with it. When Prohibition came into effect in 1920, distilleries across the nation closed. In order to distance themselves from any association with alcohol, the emerging apple industry began heavily promoting the phrase, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

Apples Come West

Early settlers to Northwest Arkansas traveled light. They could bring only the necessities to their new home—tools, livestock, furniture, clothing, bedding, cooking vessels, and plants and seeds. Apples were an important food source on the frontier. Apples were consumed fresh of course, baked, fried, or eaten straight from the tree. Firm late-season apples could be kept all winter long. But in an era before electric refrigeration, apples had to be processed if they were going to be kept for a long time. They could be cooked down into apple butter (a thick, sweet paste) or they could be sliced, dried, and later rehydrated in hot water for pies and cobblers. Their juice could be turned into vinegar, fermented into cider, or distilled into alcohol.

The First Nurserymen

When the first settlers arrived in the 1820s and 1830s they found that the area’s fertile soil, good climate, and high elevations were just right for growing fruit. They planted their seeds and young apple trees and began taming the land. Soon nurserymen set up shop, developing and testing new varieties and selling their product to new settlers. Some of the first commercial growers in Northwest Arkansas were James B. Russell and Earls Holt, both of Boonsboro (later known as Cane Hill), one of the earliest settlements in Washington County. Legend has it that the first commercial apple orchard in the state was planted near Maysville by a Cherokee woman and her enslaved Africans. After the Civil War she couldn’t afford to pay for labor so the orchard went into decline. H. S. Mundell purchased her land and began tending the neglected trees. Goldsmith Davis started his nursery business near Bentonville in 1869 with apple seeds planted by his mother. He began grafting the seedlings and built up his stock so much that at one point he had over 1,000,000 young trees (many of which were probably Ben Davis variety), which he shipped to almost every state.

Why So Many Varieties?

It was important for the home orchardist to grow a variety of apple trees to spread the harvest from early summer to late fall. Different apples had different qualities. Some were good for cooking, some kept a long time, and some made flavorful cider.

Even though nurserymen propagated trees, many folks planted apple seeds. It was a very democratic process. Anyone who planted a seed had a chance of discovering the perfect fruit in their orchard. Everybody wanted to develop a great apple, the apple that would make them rich. In 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair, Arkansas won awards for “a collection of sixty new and unnamed seedling varieties, many of which show considerable merit.”

It’s thought that over 300 varieties were grown in the area with such fanciful names as Nickerjack, Sheepnose, Brightwater, August Red, Mammoth, and 80-Ounce Pippin. Over 50 varieties were developed locally.

“The climatic conditions are so superior for the production of fruit that it is estimated that if all the orchards in Benton county . . . were consolidated into one, it would cover . . . ten square miles. . . . To all who are honorably inclined, industrious and desirous of happy home, Bentonville extends a cordial welcome.”

Bentonville Democrat, August 26, 1899

John and Martha Hann, Friendship Community southwest of West Fork, about 1908. Elsie Cress Young Collection (S-85-129-32)

About Apples

Johnny Appleseed’s mission of planting apple seeds wasn’t about growing apples for pies, but for cider making. That’s because apple seeds don’t grow true. A seed from a Granny Smith apple doesn’t grow into a tree bearing Granny Smiths.

Apples grown from seed are often bitter or sour. But every now and then a seed grows into a tree which produces a flavorful apple. In order to replicate the fruit, a scion (prepared twig) from the desired tree is grafted onto a sturdy rootstock. That is, the plant tissue from one tree is “fused” into the plant tissue of another tree. The resulting tree is a clone of the parent tree. Trees grown from seed are considered “seedling varieties.” Trees grown from grafts are considered “propagated varieties.”

During the 1700s and 1800s most people in the U.S. drank apples, rather than ate them. They turned their apple crop into cider (what we now call hard cider) a more popular drink than water, wine, beer, or coffee. A mildly alcoholic beverage, cider was easier and safer to make than corn liquor. Apple juice could also be distilled into high-proof apple brandy and applejack. In Northwest Arkansas folks probably made cider at home, but there isn’t evidence of commercial cider mills like there were in the East or Midwest. It may be that folks better trusted the water in the Ozarks.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that apples were primarily considered a food crop. Around the turn of the 20th century groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union began fighting alcohol and the evils associated with it. When Prohibition came into effect in 1920, distilleries across the nation closed. In order to distance themselves from any association with alcohol, the emerging apple industry began heavily promoting the phrase, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

Apples Come West

Early settlers to Northwest Arkansas traveled light. They could bring only the necessities to their new home—tools, livestock, furniture, clothing, bedding, cooking vessels, and plants and seeds. Apples were an important food source on the frontier. Apples were consumed fresh of course, baked, fried, or eaten straight from the tree. Firm late-season apples could be kept all winter long. But in an era before electric refrigeration, apples had to be processed if they were going to be kept for a long time. They could be cooked down into apple butter (a thick, sweet paste) or they could be sliced, dried, and later rehydrated in hot water for pies and cobblers. Their juice could be turned into vinegar, fermented into cider, or distilled into alcohol.

The First Nurserymen

When the first settlers arrived in our area in the 1820s and 1830s they found that the area’s fertile soil, good climate, and high elevations were just right for growing fruit. They planted their seeds and young apple trees and began taming the land. Soon nurserymen set up shop, developing and testing new varieties and selling their product to new settlers. Some of the first commercial growers in Northwest Arkansas were James B. Russell and Earls Holt, both of Boonsboro (later known as Cane Hill), one of the earliest settlements in Washington County. Legend has it that the first commercial apple orchard in the state was planted near Maysville by a Cherokee woman and her enslaved Africans. After the Civil War she couldn’t afford to pay for labor so the orchard went into decline. H. S. Mundell purchased her land and began tending the neglected trees. Goldsmith Davis started his nursery business near Bentonville in 1869 with apple seeds planted by his mother. He began grafting the seedlings and built up his stock so much that at one point he had over 1,000,000 young trees (many of which were probably Ben Davis variety), which he shipped to almost every state.

Why So Many Varieties?

It was important for the home orchardist to grow a variety of apple trees to spread the harvest from early summer to late fall. Different apples had different qualities. Some were good for cooking, some kept a long time, and some made flavorful cider.

Even though nurserymen propagated trees, many folks planted apple seeds. It was a very democratic process. Anyone who planted a seed had a chance of discovering the perfect fruit in their orchard. Everybody wanted to develop a great apple, the apple that would make them rich. In 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair, Arkansas won awards for “a collection of sixty new and unnamed seedling varieties, many of which show considerable merit.”

It’s thought that over 300 varieties were grown in the area with such fanciful names as Nickerjack, Sheepnose, Brightwater, August Red, Mammoth, and 80-Ounce Pippin. Over 50 varieties were developed locally.

“The climatic conditions are so superior for the production of fruit that it is estimated that if all the orchards in Benton county . . . were consolidated into one, it would cover . . . ten square miles. . . . To all who are honorably inclined, industrious and desirous of happy home, Bentonville extends a cordial welcome.”

Bentonville Democrat, August 26, 1899

The Heyday of the Apple Industry

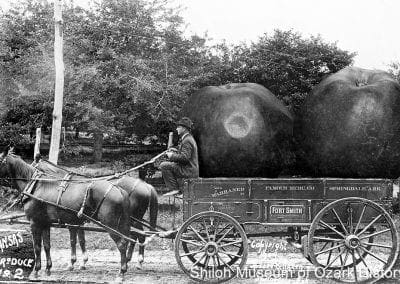

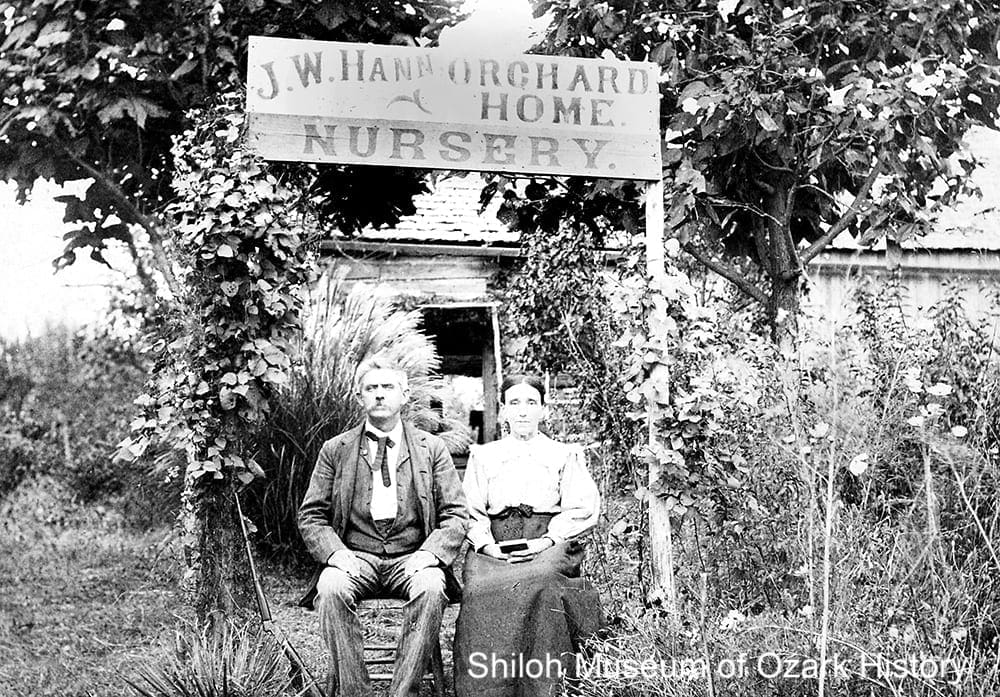

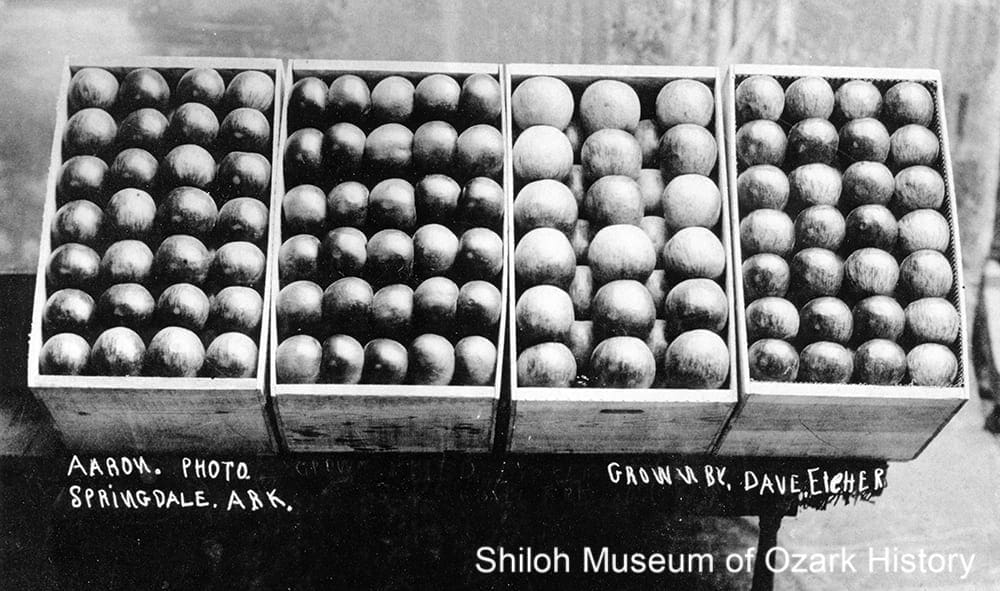

Apples grown by Dave Eicher, Springdale, 1900s-1910s. Sydney D. Aaron, photographer. Dr. Roy C. Rom Collection (S-82-34-41)

The Railroad Comes Through

Transportation played a major role in the growth of the apple industry. At first few apples were grown for market because Northwest Arkansas didn’t have a railroad line or major navigable river. Apples had to be hauled by wagon great distances before they could be shipped. With the coming of the railroad in the 1880s, growers began planting apple trees by the thousands.

Not only did the railroad ship apples, it bought huge tracts of land, promoting the acreage in brochures with such titles as “Fruit Farming Along the Frisco.” While every county in Northwest Arkansas grew and shipped apples, Benton and Washington Counties were the major players. Arkansas apples won top prizes at expositions from the 1870s to the 1910s.

Scientific Orcharding

With orcharding becoming a big business, growers sought ways to increase their crop yield. As a 1908 Springdale News article saw it, the “era of scientific orcharding” had begun. National and state agricultural agencies set up research and experimental stations to test new practices, teach, and spread practical information to farmers. At the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, researchers began studying and improving techniques for grafting, pruning, and spraying.

Apples were so important in Northwest Arkansas that in 1906, with the help of Senator James Berry of Bentonville and the state horticultural society, a first-class U.S. Weather Bureau opened on the Bentonville square. Not only did it offer daily forecasts, it sent notices to fruit farmers regarding when to spray their trees for insects and disease.

This intensive planting of orchards and attention to scientific growing methods paid off. Bumper crops of apples were reported year after year. Accounts vary but in 1919 the total apple crop in Benton County was valued at almost $5.5 million. There were over 3,100 railroad cars of fresh apples, 250 cars of dried apples, and 618 cars of apples for vinegar. About 90,000 bushels of apples went to the canning factories.

New Businesses Develop

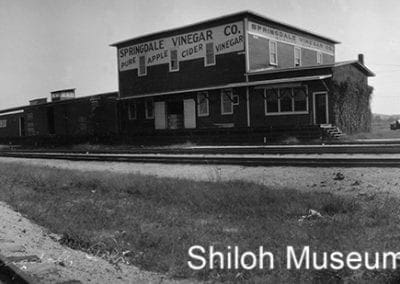

With the growth of the apple industry came a number of specialty businesses. Apple trees were propagated and grown at area nurseries. Barrels made from locally grown timber were used to ship high-grade fruit when it was green (not fully ripened) and better able to resist bruising. Ice from ice plants helped cool down refrigerated railroad cars. Cold storage plants overwintered apples before shipping them out in the spring.

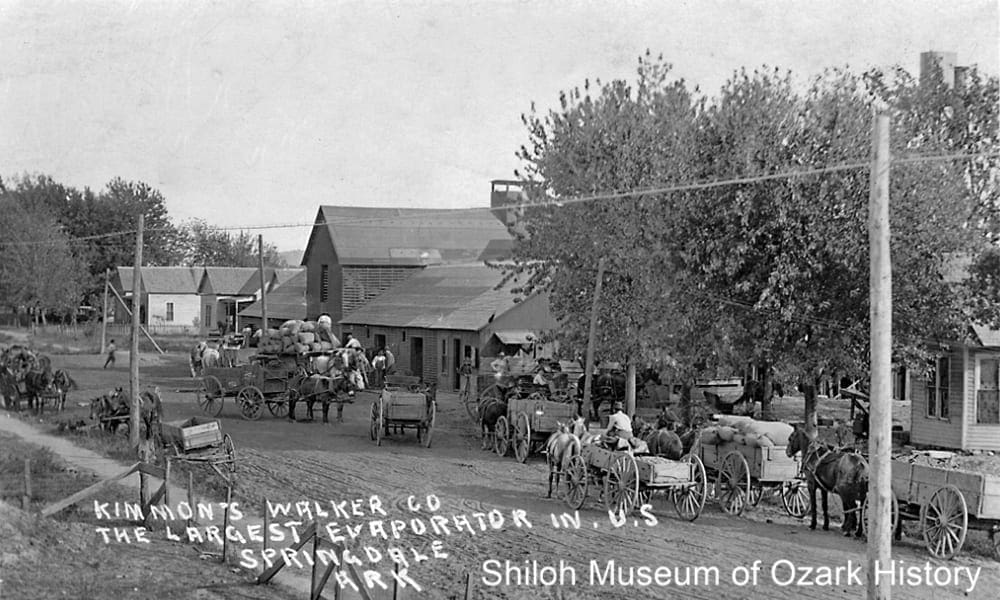

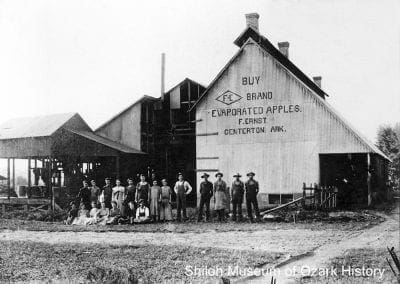

Medium-grade apples were sent to the canneries for canning or to the evaporators to be sliced and dried. Low-grade fruit was sold in bulk and turned into vinegar or alcohol at the distillery. The Kimmons, Walker and Company evaporator in Springdale was said to have been the biggest plant in the area. In 1907 over 1,500 bushels of apples were processed daily. The women working at one of the company’s 18 peelers were paid from 75¢ to $1 a day, depending on their skill.

Wholesalers and fruit brokers bought fresh fruit from the growers or processed apple products, selling these items to distant markets. During the busy season thousands of men, women, and children were employed in the orchards picking apples and in the packing sheds, distilleries, vinegar plants, and evaporators. So many people benefitted from “King Apple” that in 1901 the apple blossom became the state flower.

To celebrate the crop that put Northwest Arkansas on the map, in the mid 1920s Rogers held spectacular Apple Blossom Festivals complete with pageants, orchard tours, and the crowning of the Apple Blossom queen. Many communities and organizations sent crepe paper blossom-covered parade floats filled with pretty girls. One year over 50,000 attendees enjoyed the show. The last festival was held in 1927. Several years of unexpected rainy, cold weather had put a damper on the proceedings. The shifting weather patterns didn’t help the apple trees, either.

“. . . acres of [apple trees] in such long rows one can not see the end of them, just long streaks of vivid red and green. . . . They will surely bring to the farmers a mint of money. You remember our mother used to say to us girls . . . “dollars don’t grow on every bush, my dear.” But dollars do grow on every apple tree in this country.”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

The Heyday of the Apple Industry

Apples grown by Dave Eicher, Springdale, 1900s-1910s. Sydney D. Aaron, photographer. Dr. Roy C. Rom Collection (S-82-34-41)

The Railroad Comes Through

Transportation played a major role in the growth of the apple industry. At first few apples were grown for market because Northwest Arkansas didn’t have a railroad line or major navigable river. Apples had to be hauled by wagon great distances before they could be shipped. With the coming of the railroad in the 1880s, growers began planting apple trees by the thousands.

Not only did the railroad ship apples, it bought huge tracts of land, promoting the acreage in brochures with such titles as “Fruit Farming Along the Frisco.” While every county in Northwest Arkansas grew and shipped apples, Benton and Washington Counties were the major players. Arkansas apples won top prizes at expositions from the 1870s to the 1910s.

Scientific Orcharding

With orcharding becoming a big business, growers sought ways to increase their crop yield. As a 1908 Springdale News article saw it, the “era of scientific orcharding” had begun. National and state agricultural agencies set up research and experimental stations to test new practices, teach, and spread practical information to farmers. At the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, researchers began studying and improving techniques for grafting, pruning, and spraying.

Apples were so important in Northwest Arkansas that in 1906, with the help of Senator James Berry of Bentonville and the state horticultural society, a first-class U.S. Weather Bureau opened on the Bentonville square. Not only did it offer daily forecasts, it sent notices to fruit farmers regarding when to spray their trees for insects and disease.

This intensive planting of orchards and attention to scientific growing methods paid off. Bumper crops of apples were reported year after year. Accounts vary but in 1919 the total apple crop in Benton County was valued at almost $5.5 million. There were over 3,100 railroad cars of fresh apples, 250 cars of dried apples, and 618 cars of apples for vinegar. About 90,000 bushels of apples went to the canning factories.

New Businesses Develop

With the growth of the apple industry came a number of specialty businesses. Apple trees were propagated and grown at area nurseries. Barrels made from locally grown timber were used to ship high-grade fruit when it was green (not fully ripened) and better able to resist bruising. Ice from ice plants helped cool down refrigerated railroad cars. Cold storage plants overwintered apples before shipping them out in the spring.

Medium-grade apples were sent to the canneries for canning or to the evaporators to be sliced and dried. Low-grade fruit was sold in bulk and turned into vinegar or alcohol at the distillery. The Kimmons, Walker and Company evaporator in Springdale was said to have been the biggest plant in the area. In 1907 over 1,500 bushels of apples were processed daily. The women working at one of the company’s 18 peelers were paid from 75¢ to $1 a day, depending on their skill.

Wholesalers and fruit brokers bought fresh fruit from the growers or processed apple products, selling these items to distant markets. During the busy season thousands of men, women, and children were employed in the orchards picking apples and in the packing sheds, distilleries, vinegar plants, and evaporators. So many people benefitted from “King Apple” that in 1901 the apple blossom became the state flower.

To celebrate the crop that put Northwest Arkansas on the map, in the mid 1920s Rogers held spectacular Apple Blossom Festivals complete with pageants, orchard tours, and the crowning of the Apple Blossom queen. Many communities and organizations sent crepe paper blossom-covered parade floats filled with pretty girls. One year over 50,000 attendees enjoyed the show. The last festival was held in 1927. Several years of unexpected rainy, cold weather had put a damper on the proceedings. The shifting weather patterns didn’t help the apple trees, either.

“. . . acres of [apple trees] in such long rows one can not see the end of them, just long streaks of vivid red and green. . . . They will surely bring to the farmers a mint of money. You remember our mother used to say to us girls . . . “dollars don’t grow on every bush, my dear.” But dollars do grow on every apple tree in this country.”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

The End, and the Revival, of the Apple Industry in the Ozarks

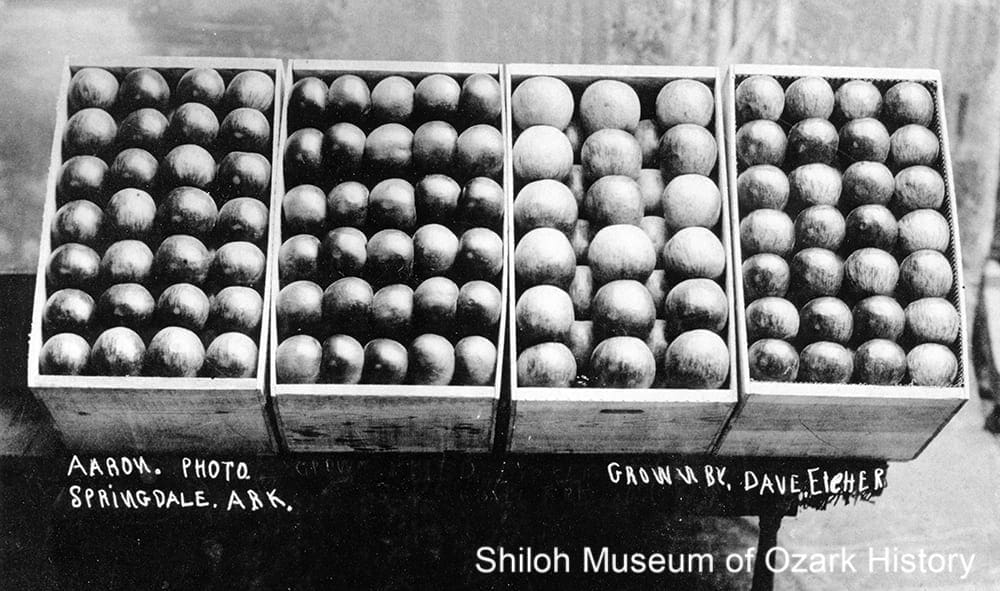

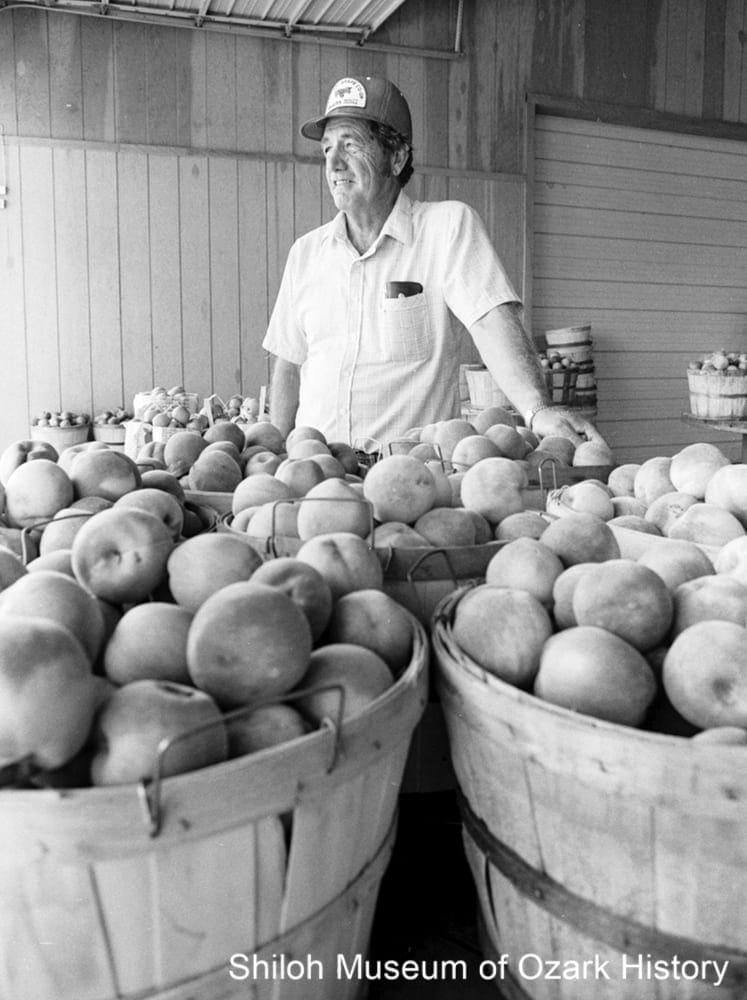

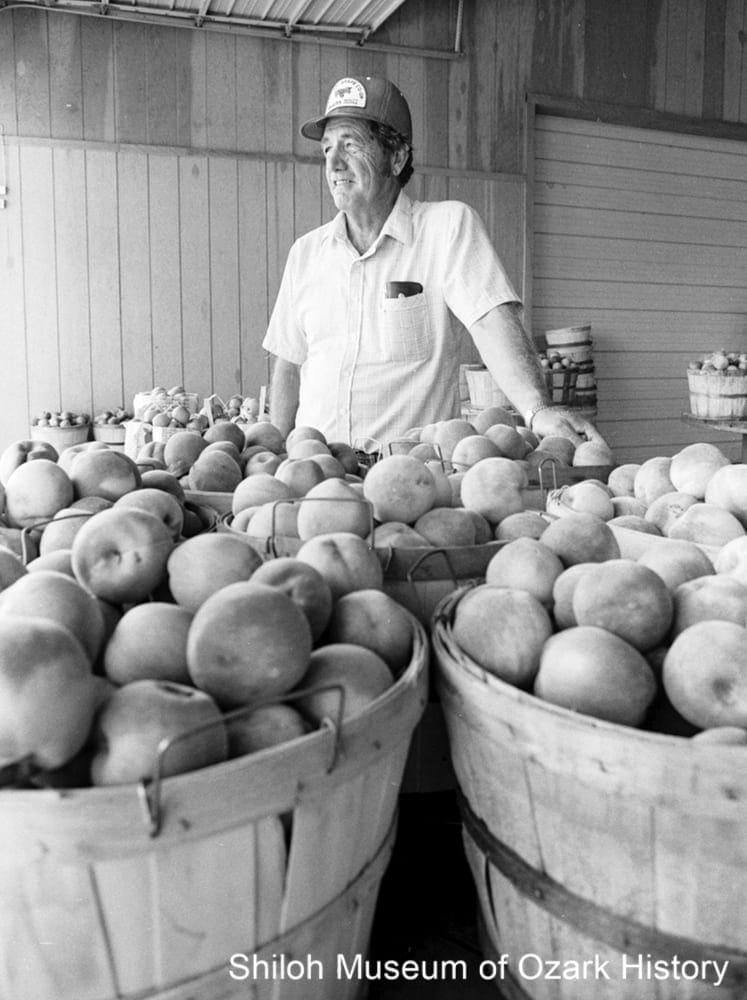

Fred Vanzant at his farm stand, Lowell, August 17, 1984. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 8-17-1984)

End of an Era

Although folks didn’t see it at the time, by the early 1920s the apple industry was in decline in Northwest Arkansas. Many factors were responsible. Lots of people got into the apple business thinking they’d get rich, but most didn’t know much about controlling pests and disease or replenishing soil nutrients. Some growers and packing houses also shipped poor quality fruit, giving area orchards a bad name. With the advent of the automobile, independent sellers could drive a truckload of fruit to a distant town to make a sale. Not only did they cut into the fruit shipper’s business, but the product quality was often poor.

Too many apple varieties meant that commercial buyers couldn’t buy enough volume of one variety. And many of the varieties weren’t the best, including the Ben Davis, one of the area’s most planted apples. As apple-growing regions out west grew in prominence, the public began to favor the new varieties. Northwest Arkansas’ growers didn’t keep up with the changing tastes. The area’s orchards were also aging.

The weather brought late freezes, droughts, or too much rain. The narrow genetic base of local apples meant that trees were more susceptible to insects and disease. San Jose scale, the coddling moth, and the oriental fruit moth wreaked havoc, as did diseases like fire blight and bitter rot. Apples were sprayed with such things as lead arsenate and “Bordeaux mixture” (lime and copper sulphate), but these treatments left a residue.

Dried apples began losing popularity in the early 1900s. Part of their decline was due to the increasing ability to preserve and transport fresh apples. Also, newly enacted federal laws like the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 placed stiff regulations on a largely unregulated business. Should inspectors find bits of peel or seed in a dried apple shipment, the load was confiscated, the shipper arrested and fined, and the fruit reprocessed in order to conform to the law. Other regulations required growers to wash apples in a weak hydrochloric acid solution before shipping to remove pesticide residue. Treated apples didn’t keep as long as untreated fruit. All of these extra steps cut into profits.

With help from the economic toll of the Great Depression, the number of apple-growing acres declined in the 1930s and 1940s. Rather than relying on apples, the area’s agricultural economy began to focus on an up-and-coming industry—poultry.

The Apple’s Revival

A few orchardists held out. In the 1950s and 1960s growers like Forrest Rodgers of Lincoln and Fred Vanzant of Lowell believed in the future of Arkansas apples. They had new products for insect and disease control and newly developed tree stock that came to maturity more quickly. In 1984 Vanzant had 60 acres of Red Delicious and Jonathan apples. Today the family still runs the farm stand.

Apple research continues at the University of Arkansas. Along with many others, Dr. Roy Rom and his son, Dr. Curt Rom, have spent decades researching and improving apple varieties. Today modern growers reduce pesticide use by using integrated pest management programs to prevent and control insect damage. Computer programs can measure temperature, humidity, and rainfall and alert a farmer to when the trees need irrigation. Smaller trees have been developed to allow more trees to be planted per acre. They’re also easier to pick.

Today’s consumers are faced with limited apple choices. Grocery stores across the nation generally offer the same varieties—Granny Smith, Jonathan, Fuji, Golden Delicious, Braeburn, Macintosh. Gone are the choices of yesteryear. Northwest Arkansas was once the biggest apple growing region of the country, but today we can’t compete with major apple-growing regions such as Washington or Oregon. Instead, small orchards are seen as the future. Consumers are increasingly interested in organic foods, heirloom plants, farmers’ markets, and the “Eat Local” movement. As these trends grow, so too does the interest for homegrown apples.

“The big, red apple will never be King in Northwest Arkansas again. That era is gone forever but its reign, in retrospect, was benign. The countryside was beautiful with trees that blossomed in the spring and were crimson with fruit in the fall. The air was clean; the water was clear.”

Thomas Rothrock

Benton County Pioneer, Summer 1974

The End, and the Revival, of the Apple Industry in the Ozarks

Fred Vanzant at his farm stand, Lowell, August 17, 1984. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 8-17-1984)

End of an Era

Although folks didn’t see it at the time, by the early 1920s the apple industry was in decline in Northwest Arkansas. Many factors were responsible. Lots of people got into the apple business thinking they’d get rich, but most didn’t know much about controlling pests and disease or replenishing soil nutrients. Some growers and packing houses also shipped poor quality fruit, giving area orchards a bad name. With the advent of the automobile, independent sellers could drive a truckload of fruit to a distant town to make a sale. Not only did they cut into the fruit shipper’s business, but the product quality was often poor.

Too many apple varieties meant that commercial buyers couldn’t buy enough volume of one variety. And many of the varieties weren’t the best, including the Ben Davis, one of the area’s most planted apples. As apple-growing regions out west grew in prominence, the public began to favor the new varieties. Northwest Arkansas’ growers didn’t keep up with the changing tastes. The area’s orchards were also aging.

The weather brought late freezes, droughts, or too much rain. The narrow genetic base of local apples meant that trees were more susceptible to insects and disease. San Jose scale, the coddling moth, and the oriental fruit moth wreaked havoc, as did diseases like fire blight and bitter rot. Apples were sprayed with such things as lead arsenate and “Bordeaux mixture” (lime and copper sulphate), but these treatments left a residue.

Dried apples began losing popularity in the early 1900s. Part of their decline was due to the increasing ability to preserve and transport fresh apples. Also, newly enacted federal laws like the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 placed stiff regulations on a largely unregulated business. Should inspectors find bits of peel or seed in a dried apple shipment, the load was confiscated, the shipper arrested and fined, and the fruit reprocessed in order to conform to the law. Other regulations required growers to wash apples in a weak hydrochloric acid solution before shipping to remove pesticide residue. Treated apples didn’t keep as long as untreated fruit. All of these extra steps cut into profits.

With help from the economic toll of the Great Depression, the number of apple-growing acres declined in the 1930s and 1940s. Rather than relying on apples, the area’s agricultural economy began to focus on an up-and-coming industry—poultry.

The Apple’s Revival

A few orchardists held out. In the 1950s and 1960s growers like Forrest Rodgers of Lincoln and Fred Vanzant of Lowell believed in the future of Arkansas apples. They had new products for insect and disease control and newly developed tree stock that came to maturity more quickly. In 1984 Vanzant had 60 acres of Red Delicious and Jonathan apples. Today the family still runs the farm stand.

Apple research continues at the University of Arkansas. Along with many others, Dr. Roy Rom and his son, Dr. Curt Rom, have spent decades researching and improving apple varieties. Today modern growers reduce pesticide use by using integrated pest management programs to prevent and control insect damage. Computer programs can measure temperature, humidity, and rainfall and alert a farmer to when the trees need irrigation. Smaller trees have been developed to allow more trees to be planted per acre. They’re also easier to pick.

Today’s consumers are faced with limited apple choices. Grocery stores across the nation generally offer the same varieties—Granny Smith, Jonathan, Fuji, Golden Delicious, Braeburn, Macintosh. Gone are the choices of yesteryear. Northwest Arkansas was once the biggest apple growing region of the country, but today we can’t compete with major apple-growing regions such as Washington or Oregon. Instead, small orchards are seen as the future. Consumers are increasingly interested in organic foods, heirloom plants, farmers’ markets, and the “Eat Local” movement. As these trends grow, so too does the interest for homegrown apples.

“The big, red apple will never be King in Northwest Arkansas again. That era is gone forever but its reign, in retrospect, was benign. The countryside was beautiful with trees that blossomed in the spring and were crimson with fruit in the fall. The air was clean; the water was clear.”

Thomas Rothrock

Benton County Pioneer, Summer 1974

Locally Developed Varieties

Arkansas (aka Mammoth Black Twig)—propagated in 1869; the scion was cut from a tree grown from the seed of either the Black Twig or Limber Twig in the 1840s by John Crawford of Rhea’s Mill near Prairie Grove; exhibited at the New Orleans Exposition in 1884

Arkansas Black—conflicting origin; some say first fruited in 1879 on Mr. Braithwait’s farm near Bentonville; others say DeKalb Holt produced it near Lincoln; firm flesh harvested in late fall; excellent for overwintering; won first place at the 1900 International Exposition in Paris

Black Ben Davis (aka Reagan’s Red)— originated from a seedling found in 1883 by John Reagan on a waste pile near an apple evaporator on Alexander Black’s farm; gained acclaim at the International Exposition in Paris

Collins’ Red (aka Collins, Champion Red, Champion, Reagan’s Red)—found by chance in a field near Lincoln; commercially propagated around 1886; a good-colored fruit which keeps well, if kept properly

Etris—discovered by Jack Etris near Gentry in the late 1800s; a tart, red-striped fruit which keeps well; reaches its full flavor in late November

Highfill Seedling (aka Highfill Blue)—discovered by Hezikiah Highfill at his nursery in Highfill; a dark red fruit with a “blue frost” and a tart “whang;” won a medal at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis

Howard Sweet—the seedling is thought to have come from Earls Holt’s Cane Hill nursery after the Civil War; grown near Cincinnati by Mr. Howard; a sweet, highly colored dessert apple; the tree has a heavy bloom

King David—originated on Ben Frost’s Durham-area farm about 1890; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with red

Oliver Red (aka Oliver, Senator)—originated in Washington County; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with bright red; harvested in early September; a good dessert apple

Shannon Pippin—brought from Indiana in 1833; a yellow-skinned fruit with a faint blush, it had a sweet aroma and made for a good dessert apple; it wasn’t suitable for commercial growing because not many apples grew on the tree

Springdale—predicted to go far in 1890, it never gained prominence; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with mixed red and bright crimson splashes

Summer Champion—from W.T. Waller’s farm near Lincoln; originally from Abraham Tull’s farm in Grant County, Arkansas; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with red; sold to Stark Brothers Nursery for $45

Wilson June—one of 1,000 trees found at the Earles Holt nursery after the Civil War and transplanted to the Lincoln area by Albert and A. J. Wilson; a sweet, yellow-skinned fruit with dark crimson stripes

Locally Developed Varieties

Arkansas (aka Mammoth Black Twig)—propagated in 1869; the scion was cut from a tree grown from the seed of either the Black Twig or Limber Twig in the 1840s by John Crawford of Rhea’s Mill near Prairie Grove; exhibited at the New Orleans Exposition in 1884

Arkansas Black—conflicting origin; some say first fruited in 1879 on Mr. Braithwait’s farm near Bentonville; others say DeKalb Holt produced it near Lincoln; firm flesh harvested in late fall; excellent for overwintering; won first place at the 1900 International Exposition in Paris

Black Ben Davis (aka Reagan’s Red)— originated from a seedling found in 1883 by John Reagan on a waste pile near an apple evaporator on Alexander Black’s farm; gained acclaim at the International Exposition in Paris

Collins’ Red (aka Collins, Champion Red, Champion, Reagan’s Red)—found by chance in a field near Lincoln; commercially propagated around 1886; a good-colored fruit which keeps well, if kept properly

Etris—discovered by Jack Etris near Gentry in the late 1800s; a tart, red-striped fruit which keeps well; reaches its full flavor in late November

Highfill Seedling (aka Highfill Blue)—discovered by Hezikiah Highfill at his nursery in Highfill; a dark red fruit with a “blue frost” and a tart “whang;” won a medal at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis

Howard Sweet—the seedling is thought to have come from Earls Holt’s Cane Hill nursery after the Civil War; grown near Cincinnati by Mr. Howard; a sweet, highly colored dessert apple; the tree has a heavy bloom

King David—originated on Ben Frost’s Durham-area farm about 1890; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with red

Oliver Red (aka Oliver, Senator)—originated in Washington County; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with bright red; harvested in early September; a good dessert apple

Shannon Pippin—brought from Indiana in 1833; a yellow-skinned fruit with a faint blush, it had a sweet aroma and made for a good dessert apple; it wasn’t suitable for commercial growing because not many apples grew on the tree

Springdale—predicted to go far in 1890, it never gained prominence; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with mixed red and bright crimson splashes

Summer Champion—from W.T. Waller’s farm near Lincoln; originally from Abraham Tull’s farm in Grant County, Arkansas; a yellow-skinned fruit washed with red; sold to Stark Brothers Nursery for $45

Wilson June—one of 1,000 trees found at the Earles Holt nursery after the Civil War and transplanted to the Lincoln area by Albert and A. J. Wilson; a sweet, yellow-skinned fruit with dark crimson stripes

A Nursery Story

Part of the strength of the apple industry in Northwest Arkansas was due to the many nurseries that sprung up, beginning in the early 19th century. A few of the larger nurseries included Crider Brothers Nursery (Greenland), Benton County Nursery Company (Rogers), Stark Brothers Nursery (Farmington), and Parker Brothers Nursery Company and its offshoot, John Parker and Son Nursery Company.

Lewis Parker began a home nursery business in Aurora (Madison County) in 1887. As the business grew his elder sons James and John helped with the nursery and began selling stock further afield. A flowery 1922 account in the Fayetteville Democrat recounts the nursery’s early years:

“As a result of these labors, hundreds of home and commercial orchards have been established. . . . Who will say that these patient, plodding men labored only for the price brought by their trees? No, these men had a vision and as they worked and helped to lay the foundation of our great fruit industry this vision lured them on. They could see in the future vast orchards, vineyards and berry farms. They sensed afar the day that is now dawning when well developed fruit lands is bringing a flow of golden wealth to good old Northwest Arkansas.”

Eventually younger sons George and Elmer joined the business. After Lewis’ retirement in the early 1900s, his sons established their own nurseries. Elmer stayed in Aurora while James went to Oklahoma. George started the Parker Brothers Nursery Company in Fayetteville, with acreage for growing stock in Greenland. John worked for the company for 20 years as salesman and “Orchard Adviser.”

Early in 1922 John established John Parker and Son Nursery Company, “a clean little nursery” in Fayetteville. His split with brother George might have been acrimonious, as John’s early letterhead included the phrase, “Not connected in any way with ‘so-called’ Parker Bros. Nursery Co.” In 1922 John recounted his business philosophy:

“Father tried to grow the best trees possible. He was a firm believer in the ‘Golden Rule’ and applied it in his business dealings. I shall never forget the few sound principles which he tried to impress on us as we were getting our first years of experience with him in the Nursery work. . . . First, learn your business so that you will know a good tree and how to produce it. Be sure that you never put a tree in a man’s order that you would not plant yourself. Be absolutely honest with everybody you deal with.”

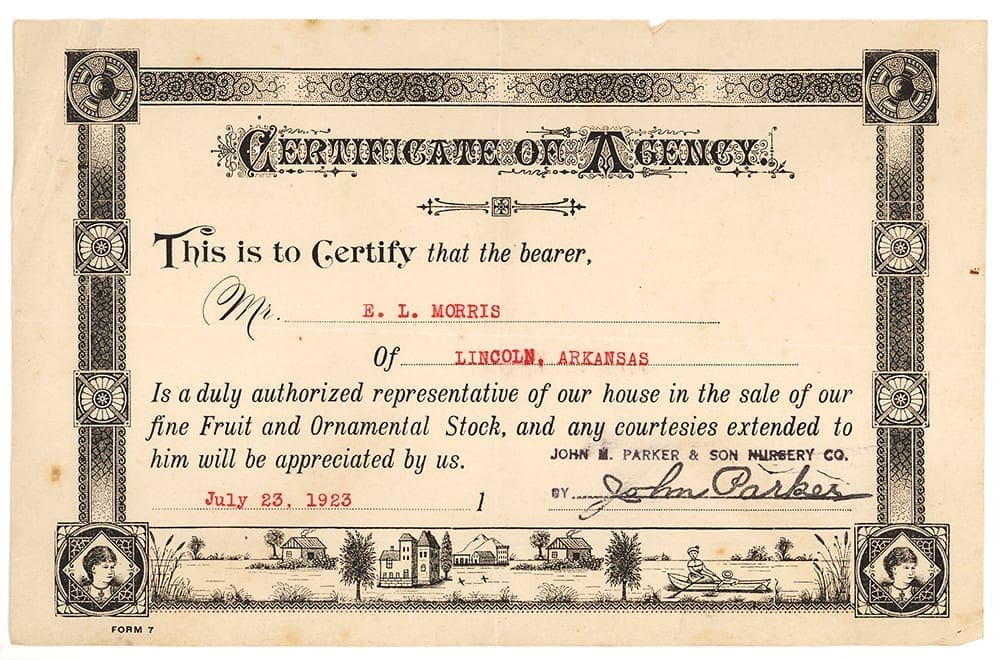

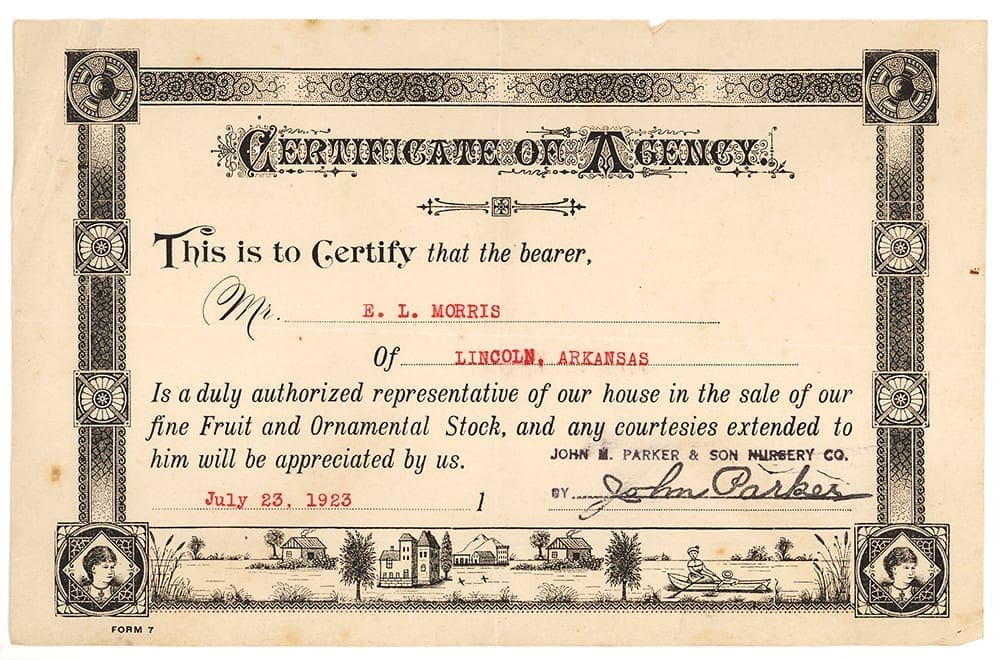

Certificate authorizing E. L. Morris of Lincoln, Arkansas, as a sales representative for Parker Brothers Nursery Company. Ruth Morris Collection

The following excerpts come from letters written to Emmett Lee Morris of Lincoln, who served first as an agent for the Parker Brothers Nursery Company before working for John M. Parker and Son Nursery Co. in 1922. Morris and his fellow agents worked on commission and were constantly being told to sell more stock, to write up orders correctly, to not promise something that couldn’t be delivered, and to follow through and get the payment due the company. The first few letters were written by George Parker; the remainder by John.

April 16, 1921

“We wish to offer here a little bit of advice to our salesmen and to stress the importance of starting early on Monday morning and to keep busy with hammer and tongs for the full six days of the week. We are lead to believe that Monday is the most important day of the week. . . . Week end vacations are all very well for retired business men, but you can’t indulge in this extravagance and stay in the business race. . . . Benjamin Franklin could not afford to waste a minute. Edison works eighteen hours a day. The men who win are the men who make every day stand on its own feet. They are Six Day Men. Are You?”

April 26, 1921

“Our letter of the 16th . . . evidently brought results as 26 men reported last week against the 14 the week before. Now men, this makes us feel optimistic. We are only two reports behind a year ago. This is fine, considering the cold, rainy, backward spring we have had, but summer is now here. . . . Remember, the more you work the more you get. Here are the ten high ones of this week. Are you a top notcher? . . . Morris $935.80, Gingles $513.75, Chamblin $340.50, Gilbert $237.94 . . . Each one of our salesmen should consider it his duty right now to suggest to his prospective customer that he plant and raise what he consumes . . . He will be apt to bring up the subject of canned fruit. Here is your opportunity. Make the best of it, and be an optimist all the time. Always read the optimistic parts of the news papers. Never read the pessimistic side.”

February 1, 1922

“Upon looking over our Sales Ledger this morning, I notice that you are not reporting, and wonder what our firm has done, or has not done, that this should be. Good opportunities and valuable time is fast passing away. I trust that the fact that you are not representing us now is not due to any discourteous or unsatisfactory treatment from this end. …It is now a desirable time to take up the work, there never was more money in circulation and more business activity in our history than at the present time, and I would like to have you represent us in your locality. Your name will be held on my desk, awaiting your prompt answer.”

October 30, 1923

“Sorry to hear you have not been able to work. . . . We can furnish the Summer Champion in the 3-4 ft. grade, but have no Shannon in stock. . . . One thing we want to avoid: Do not make a fellow believe that they will be 3-4 ft. and if the order is written is written up 2-3 ft. that is the grade we will send him. We guarantee the roots to be absolutely No. 1. . . .”

March 11, 1924

“We wish to thank you for the $108.10 and will say that we think you are handling that business very nicely, at least we are perfectly satisfied with your work.”

August 27, 1924

“You do not need a permit to sell trees in Oklahoma. However, we will guarantee to get you out of jail, and if you get in trouble we will pay the expenses. . . . We are very glad to hear that you have a car and that you are going to work at once. I believe the month of September and October will be the best two months in this year.”

December 4, 1924

“Please find enclosed our check for $3.12, the 10% advance commission due on your last report which amounted to $31.28.”

February 10, 1925

“I do not know just how the packing crew happened to leave C.E. Phillips order out. It was shipped out by C.O.D. express direct to him Feb. 7th. Roll in the orders as fast as possible. We will deliver the goods.”

February 10, 1925

“I wish that you were in the office so I could take my hat off to you. I would willingly expose my marble top to the man that gets one hundred cents on the dollar. . . . We are glad to know that you have prospects for more good business. Hit while the iron is hot. We all know we are giving the farmer the best deal he has ever had from any nursery company.”

February 18, 1925

“We sold over $700.00 cash business from the office that day, and got the money. About $300.00 yesterday. Get in the ring and tell the boys they had better close the deal now.”

December 4, 1925

“We note what you say in regard to Mr. Glidewell’s order. In regard to replacing, we will stand one-half the loss, but we really believe the dry weather was responsible for most of this loss.”

February 18, 1926

“We received a notice from the P.M. [postmaster] at Summers, that G.E. Hall had refused to accept his bill of nursery stock which we shipped out a few days ago. We would like for you to see what is the matter with him, and try to deliver it if possible. We cannot understand why he does not want it now, as this is fine weather for planting. We have written him telling him to call and get his stock at once, but we believe you had better see about it too, as he may be a pretty hard one to convince.”

March 12, 1926

“Just received your letter, and are glad to know you had 100% collections, and we always know that you will get the money when we ship to your customers. Will be glad to see you whenever you can come up with the money.”

January 21, 1928

“Don’t let anybody get by if they want to buy apples, peach, plum, pear or cherries.”

March 15, 1928

“We are wondering why it is you have not sent in some orders. You surely are not working very hard, as I am sure there is a number of people not far from where you live who want to buy some of our good trees. . . . Please put in at least 1 or 2 days and get some orders and rush them to us.”

March 19, 1929

“I was very much disappointed that I failed to meet you in the office this afternoon. I gave your boy samples of Stayman Winesap and we have a big surplus in Stayman, Red Delicious and Black Ben Davis in this extra fine 2 year old tree. Sell them at $20.00 per hundred if you can. If they take 50 or more sell them at 20¢. We will give you ¼ of all the money we collect. . . . We would like for you to go out and work a few days and see how much you can make. Rush the orders to us and if you have to give a fellow a Golden Delicious to buy, tell him we are making him a present of the same kind of tree that Stark Brothers sell for $1.50. Anything to get the business and we always appreciate your business because we have never failed to get the money on your orders.” Yours for More and Better Fruit, John Parker

A Nursery Story

Part of the strength of the apple industry in Northwest Arkansas was due to the many nurseries that sprung up, beginning in the early 19th century. A few of the larger nurseries included Crider Brothers Nursery (Greenland), Benton County Nursery Company (Rogers), Stark Brothers Nursery (Farmington), and Parker Brothers Nursery Company and its offshoot, John Parker and Son Nursery Company.

Lewis Parker began a home nursery business in Aurora (Madison County) in 1887. As the business grew his elder sons James and John helped with the nursery and began selling stock further afield. A flowery 1922 account in the Fayetteville Democrat recounts the nursery’s early years:

“As a result of these labors, hundreds of home and commercial orchards have been established. . . . Who will say that these patient, plodding men labored only for the price brought by their trees? No, these men had a vision and as they worked and helped to lay the foundation of our great fruit industry this vision lured them on. They could see in the future vast orchards, vineyards and berry farms. They sensed afar the day that is now dawning when well developed fruit lands is bringing a flow of golden wealth to good old Northwest Arkansas.”

Eventually younger sons George and Elmer joined the business. After Lewis’ retirement in the early 1900s, his sons established their own nurseries. Elmer stayed in Aurora while James went to Oklahoma. George started the Parker Brothers Nursery Company in Fayetteville, with acreage for growing stock in Greenland. John worked for the company for 20 years as salesman and “Orchard Adviser.”

Early in 1922 John established John Parker and Son Nursery Company, “a clean little nursery” in Fayetteville. His split with brother George might have been acrimonious, as John’s early letterhead included the phrase, “Not connected in any way with ‘so-called’ Parker Bros. Nursery Co.” In 1922 John recounted his business philosophy:

“Father tried to grow the best trees possible. He was a firm believer in the ‘Golden Rule’ and applied it in his business dealings. I shall never forget the few sound principles which he tried to impress on us as we were getting our first years of experience with him in the Nursery work. . . . First, learn your business so that you will know a good tree and how to produce it. Be sure that you never put a tree in a man’s order that you would not plant yourself. Be absolutely honest with everybody you deal with.”

Certificate authorizing E. L. Morris of Lincoln, Arkansas, as a sales representative for Parker Brothers Nursery Company. Ruth Morris Collection

The following excerpts come from letters written to Emmett Lee Morris of Lincoln, who served first as an agent for the Parker Brothers Nursery Company before working for John M. Parker and Son Nursery Co. in 1922. Morris and his fellow agents worked on commission and were constantly being told to sell more stock, to write up orders correctly, to not promise something that couldn’t be delivered, and to follow through and get the payment due the company. The first few letters were written by George Parker; the remainder by John.

April 16, 1921

“We wish to offer here a little bit of advice to our salesmen and to stress the importance of starting early on Monday morning and to keep busy with hammer and tongs for the full six days of the week. We are lead to believe that Monday is the most important day of the week. . . . Week end vacations are all very well for retired business men, but you can’t indulge in this extravagance and stay in the business race. . . . Benjamin Franklin could not afford to waste a minute. Edison works eighteen hours a day. The men who win are the men who make every day stand on its own feet. They are Six Day Men. Are You?”

April 26, 1921

“Our letter of the 16th . . . evidently brought results as 26 men reported last week against the 14 the week before. Now men, this makes us feel optimistic. We are only two reports behind a year ago. This is fine, considering the cold, rainy, backward spring we have had, but summer is now here. . . . Remember, the more you work the more you get. Here are the ten high ones of this week. Are you a top notcher? . . . Morris $935.80, Gingles $513.75, Chamblin $340.50, Gilbert $237.94 . . . Each one of our salesmen should consider it his duty right now to suggest to his prospective customer that he plant and raise what he consumes . . . He will be apt to bring up the subject of canned fruit. Here is your opportunity. Make the best of it, and be an optimist all the time. Always read the optimistic parts of the news papers. Never read the pessimistic side.”

February 1, 1922

“Upon looking over our Sales Ledger this morning, I notice that you are not reporting, and wonder what our firm has done, or has not done, that this should be. Good opportunities and valuable time is fast passing away. I trust that the fact that you are not representing us now is not due to any discourteous or unsatisfactory treatment from this end. …It is now a desirable time to take up the work, there never was more money in circulation and more business activity in our history than at the present time, and I would like to have you represent us in your locality. Your name will be held on my desk, awaiting your prompt answer.”

October 30, 1923

“Sorry to hear you have not been able to work. . . . We can furnish the Summer Champion in the 3-4 ft. grade, but have no Shannon in stock. . . . One thing we want to avoid: Do not make a fellow believe that they will be 3-4 ft. and if the order is written is written up 2-3 ft. that is the grade we will send him. We guarantee the roots to be absolutely No. 1. . . .”

March 11, 1924

“We wish to thank you for the $108.10 and will say that we think you are handling that business very nicely, at least we are perfectly satisfied with your work.”

August 27, 1924

“You do not need a permit to sell trees in Oklahoma. However, we will guarantee to get you out of jail, and if you get in trouble we will pay the expenses. . . . We are very glad to hear that you have a car and that you are going to work at once. I believe the month of September and October will be the best two months in this year.”

December 4, 1924

“Please find enclosed our check for $3.12, the 10% advance commission due on your last report which amounted to $31.28.”

February 10, 1925

“I do not know just how the packing crew happened to leave C.E. Phillips order out. It was shipped out by C.O.D. express direct to him Feb. 7th. Roll in the orders as fast as possible. We will deliver the goods.”

February 10, 1925

“I wish that you were in the office so I could take my hat off to you. I would willingly expose my marble top to the man that gets one hundred cents on the dollar. . . . We are glad to know that you have prospects for more good business. Hit while the iron is hot. We all know we are giving the farmer the best deal he has ever had from any nursery company.”

February 18, 1925

“We sold over $700.00 cash business from the office that day, and got the money. About $300.00 yesterday. Get in the ring and tell the boys they had better close the deal now.”

December 4, 1925

“We note what you say in regard to Mr. Glidewell’s order. In regard to replacing, we will stand one-half the loss, but we really believe the dry weather was responsible for most of this loss.”

February 18, 1926

“We received a notice from the P.M. [postmaster] at Summers, that G.E. Hall had refused to accept his bill of nursery stock which we shipped out a few days ago. We would like for you to see what is the matter with him, and try to deliver it if possible. We cannot understand why he does not want it now, as this is fine weather for planting. We have written him telling him to call and get his stock at once, but we believe you had better see about it too, as he may be a pretty hard one to convince.”

March 12, 1926

“Just received your letter, and are glad to know you had 100% collections, and we always know that you will get the money when we ship to your customers. Will be glad to see you whenever you can come up with the money.”

January 21, 1928

“Don’t let anybody get by if they want to buy apples, peach, plum, pear or cherries.”

March 15, 1928

“We are wondering why it is you have not sent in some orders. You surely are not working very hard, as I am sure there is a number of people not far from where you live who want to buy some of our good trees. . . . Please put in at least 1 or 2 days and get some orders and rush them to us.”

March 19, 1929

“I was very much disappointed that I failed to meet you in the office this afternoon. I gave your boy samples of Stayman Winesap and we have a big surplus in Stayman, Red Delicious and Black Ben Davis in this extra fine 2 year old tree. Sell them at $20.00 per hundred if you can. If they take 50 or more sell them at 20¢. We will give you ¼ of all the money we collect. . . . We would like for you to go out and work a few days and see how much you can make. Rush the orders to us and if you have to give a fellow a Golden Delicious to buy, tell him we are making him a present of the same kind of tree that Stark Brothers sell for $1.50. Anything to get the business and we always appreciate your business because we have never failed to get the money on your orders.” Yours for More and Better Fruit, John Parker

Prunings of Apple History

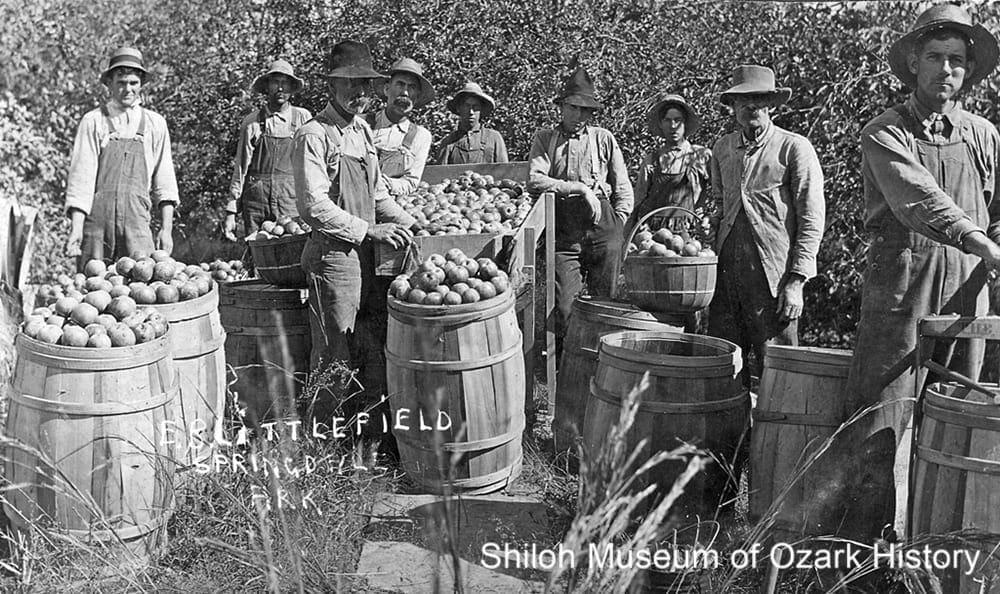

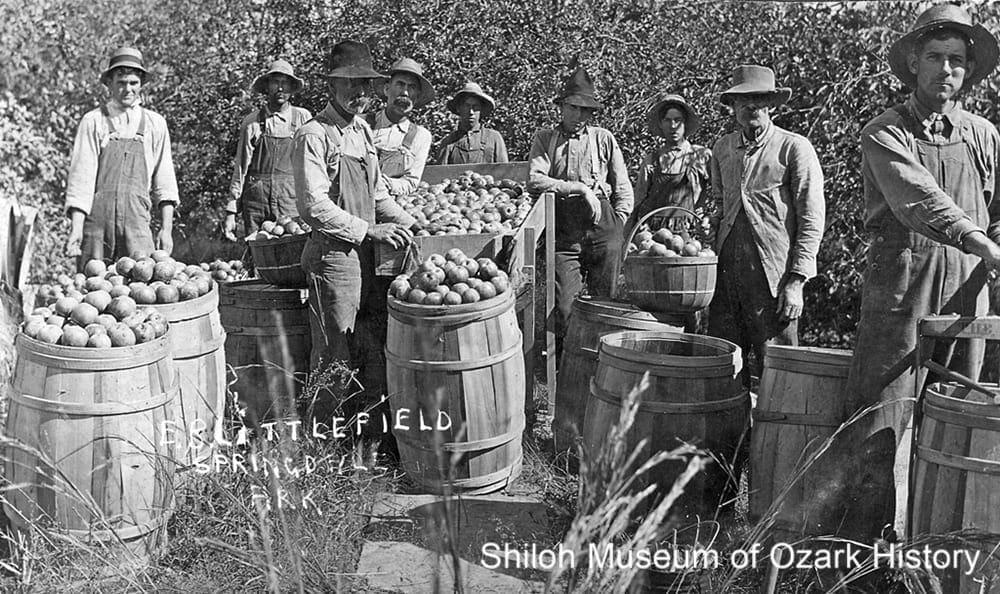

E. B. Littlefield orchard east of Springdale, circa 1910. Dr. Lloyd O. Warren Collection (S-82-214-4)

“The apple is the king of fruits, and the mountains of Arkansas form its throne. Hurrah for Arkansas, for our fine flavored apples . . .”

Springdale News, October 30, 1894

“Verily, as the poet says, “God dreamed of apple trees” when his hand created these delightful hills and hollows, these wide plateaus and gentle slopes, for this is the world’s greatest apple orchard . . .”

John T. Stinson

Fruit Growing Along the Frisco System, 1904

“The countryside was beautiful with trees that blossomed fragrantly in the spring and were crimson with fruit in the autumn. . . . For me, the apple blossom festivals held in Rogers during the 1920s were symbolic of the beauty that was once down Northwest Arkansas’s lanes; and which brought the apple blossom to be the State Flower of Arkansas.”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“We had a winesap, a tart-sweet apple, and a good “keeper”—we always tried to retain a few bushels in the root cellar, where they lasted well into the winter. Ingrams, a small sweet apple were the very best “keeper.” . . . I remember one [tree] that bore fruit which ripened early, but never lost its green color. We called them “June Apples.” They were so sweet that there were occasional pockets of crystallized sugar near the core. Also we had Arkansas Blacks, a yellow-fleshed apple, so dark red that it was almost black, firm, sweet, juicy.”

Caryn Schmitt and Steven Finney

Flashback, August 1986

“Pruning was commenced at once and continued all winter whenever the weather was mild. No pruning was allowed when the wood was in a frozen condition. . . . Weak, interfering and dead limbs were cut out, strong ones often shortened in to balance the tops. . . . [C]are was used to cut back to a fair-sized limb in a good position to continue growth and assist in healing the wound.”

Springdale News, February 21, 1908

“Orchard men from various other sections of the country began to discover that this region was most admirably adapted to horticulture, with the apple as the prime minister of progress. Rolling acres where from prehistoric days the forest had flourished were turned into symmetrical orchards, the flourishing trees burdened with plump fruit . . .”

John T. Stinson

Fruit Growing Along the Frisco System, 1904

“There is no longer little doubt about the beneficial results of spraying . . . It means better fruit and more fruit, and The News predicts that the time is not far distant when Northwest Arkansas will be up with other fruit sections in this particular.”

Springdale News, April 25, 1908

“My father [Harvey W. Gipple] held that insects would eventually become immune to the chemicals used in the spray material… Growers sprayed summer and winter but still there were diseases and insects which caused the fruit to be of an inferior quality. They thought the spray materials were diluted or had lost their effectiveness, but they finally realized—just as my father had thought—worms had become immune to the chemicals . . .”

Pearl Gipple Banks

Benton County Pioneer, July 1957

Anglin family working at Rupple’s apple shed, Fayetteville, circa 1910. Lois Conduff Collection (S-87-276-1)

“During World War I men laborers were scarce and Reed [Adcock] hired a number of us boys to pick apples for him . . . Someone threw an apple, another did the same, and that started the ball to rolling. . . . Almost spontaneously apples began to fly . . . The next morning . . . [Adcock] told us in a very kind way that the program had changed. From now on, he said, I shall pay you 5¢ per bushel for picking apples, instead by the day.”

A. D. Lester

Benton County Pioneer, Summer 1972

“In the packing house [operated by Teasdale Fruit and Nut Products Co.] under the supervision of Miss Lizzie McFarlin, all were so busy and everything so nice and clean. The fruit is packed in 50-pound boxes, which are all nicely paperlined, carefully faced and made pretty by the use of lace paper.”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

“From every source and from all parts of the country come complaints of last season’s packing of apples. The wholesalers denounce the packing of inferior fruit, because it has shut off consumption; the retailers have had grievance for the same reason and the consumer has been so disgusted he has simply passed the apples by and has bought oranges and bananas instead.”

Springdale News, June 15, 1908

“There would be such a line, we would take the truck over and leave it. A man would stay with it to pull it up. And at noon someone would take his place. We’d be lucky if we got it unloaded that day. And this was in the 1930s when the apple business was sort of winding down.”

Jack Yates

Benton County Daily Democrat, March 1, 1987

“As the hundreds of carloads were dispatched . . . Secretary Stroud’s office [of the Ozark Fruit Growers Association] . . . was kept in touch with the market conditions in cities from Denver and St. Paul eastward by representatives and salesmen who quoted prices . . . the refrigerator cars of local fruit were sent to points where there was the greatest demand. . . . Constant communications by wire kept the output of fruit from glutting any particular market, and results were soon evident in better prices to the grower.”

Will Plank

Benton County Pioneer, March 1963

“There is much more to a glass of cider than just squeezing apples so over came Cleva and Harry Douglas [of Rogers] with buckets and baskets, tubs and sacks . . . There were a few discussions with bees and wasps as to just which apples belonged to whom, but I didn’t push the issue, and let them have a fair share.”

Lanette Tillman

Oklahoma Ranch and Farm World, April 13, 1969

“Owing to the extensive apple orchards and the large returns received from the crops, much attention is being paid to methods of care and cultivation . . . as well as packing and marketing the fruit. It has been our observation that the grower who gives his orchard good care and cultivation is repaid many times over for the extra expense.”

Fruit Farming Along the Frisco, 1899

“The [Southern Fruit Products Co.] factory is nearly as large as all out doors. Uses apples of all grades, large and small, and has a capacity of 3,500 bushels per day and even then the bins get to running over though they work night and day. Last year it made 530,000 gallons of vinegar which finds its way to every section of the Union. Sells by the train load. Just think of that, Betsey, train loads of vinegar!”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

“The Macon and Carson distillery has up to the present date used something over 30,000 bushels of apples in the manufacture of brandy. They expect before the season is over to use over a quarter of a million bushels of fruit.”

Unknown source, September 1899

(quoted by Robert G. Winn, Washington County Observer, 1970s–1980s)

“The apples were peeled, sliced, then dried by a night crew over wood stoves. Sulphur was thrown on the fires, the resulting vapors preventing the apple slices from turning too brown. When ready to market, the dried apples were sprinkled with soda water and then packed into wooden or pasteboard boxes.”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“The National Pure Food Commission seems to think that the use of sulphur will be a violation of the pure food law. . . . If Sulphur is barred from use in bleaching fruit, it will work great injury to the business and affect not only the evaporator men, but all who grow fruit.”

Springdale News, March 6, 1908

“. . . no commercial apple has even been as well adapted to Northwest Arkansas’s climate and soil as the Ben Davis; and probably no apple will ever be. . . . Said a Louisiana native to an Arkansas apple peddler, ‘That man Benny Davis up there sho’ do grow the apples.'”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“The awards on apples [at the Chicago World’s Fair] have just been made and the Arkansas display . . . secured the highest award for the largest and best display of apples. . . . New York had long been noted for her apples but they did not begin to compare with the fruit from Arkansas, which was a great revelation to most of the people, who looked upon Arkansas as a wilderness.”

Springdale News, October 30, 1893

Prunings of Apple History

E. B. Littlefield orchard east of Springdale, circa 1910. Dr. Lloyd O. Warren Collection (S-82-214-4)

“The apple is the king of fruits, and the mountains of Arkansas form its throne. Hurrah for Arkansas, for our fine flavored apples . . .”

Springdale News, October 30, 1894

“Verily, as the poet says, “God dreamed of apple trees” when his hand created these delightful hills and hollows, these wide plateaus and gentle slopes, for this is the world’s greatest apple orchard . . .”

John T. Stinson

Fruit Growing Along the Frisco System, 1904

“The countryside was beautiful with trees that blossomed fragrantly in the spring and were crimson with fruit in the autumn. . . . For me, the apple blossom festivals held in Rogers during the 1920s were symbolic of the beauty that was once down Northwest Arkansas’s lanes; and which brought the apple blossom to be the State Flower of Arkansas.”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“We had a winesap, a tart-sweet apple, and a good “keeper”—we always tried to retain a few bushels in the root cellar, where they lasted well into the winter. Ingrams, a small sweet apple were the very best “keeper.” . . . I remember one [tree] that bore fruit which ripened early, but never lost its green color. We called them “June Apples.” They were so sweet that there were occasional pockets of crystallized sugar near the core. Also we had Arkansas Blacks, a yellow-fleshed apple, so dark red that it was almost black, firm, sweet, juicy.”

Caryn Schmitt and Steven Finney

Flashback, August 1986

“Pruning was commenced at once and continued all winter whenever the weather was mild. No pruning was allowed when the wood was in a frozen condition. . . . Weak, interfering and dead limbs were cut out, strong ones often shortened in to balance the tops. . . . [C]are was used to cut back to a fair-sized limb in a good position to continue growth and assist in healing the wound.”

Springdale News, February 21, 1908

“Orchard men from various other sections of the country began to discover that this region was most admirably adapted to horticulture, with the apple as the prime minister of progress. Rolling acres where from prehistoric days the forest had flourished were turned into symmetrical orchards, the flourishing trees burdened with plump fruit . . .”

John T. Stinson

Fruit Growing Along the Frisco System, 1904

“There is no longer little doubt about the beneficial results of spraying . . . It means better fruit and more fruit, and The News predicts that the time is not far distant when Northwest Arkansas will be up with other fruit sections in this particular.”

Springdale News, April 25, 1908

“My father [Harvey W. Gipple] held that insects would eventually become immune to the chemicals used in the spray material . . . Growers sprayed summer and winter but still there were diseases and insects which caused the fruit to be of an inferior quality. They thought the spray materials were diluted or had lost their effectiveness, but they finally realized—just as my father had thought—worms had become immune to the chemicals . . .”

Pearl Gipple Banks

Benton County Pioneer, July 1957

Anglin family working at Rupple’s apple shed, Fayetteville, circa 1910. Lois Conduff Collection (S-87-276-1)

“During World War I men laborers were scarce and Reed [Adcock] hired a number of us boys to pick apples for him . . . Someone threw an apple, another did the same, and that started the ball to rolling. . . . Almost spontaneously apples began to fly . . . The next morning . . . [Adcock] told us in a very kind way that the program had changed. From now on, he said, I shall pay you 5¢ per bushel for picking apples, instead by the day.”

A. D. Lester

Benton County Pioneer, Summer 1972

“In the packing house [operated by Teasdale Fruit and Nut Products Co.] under the supervision of Miss Lizzie McFarlin, all were so busy and everything so nice and clean. The fruit is packed in 50-pound boxes, which are all nicely paperlined, carefully faced and made pretty by the use of lace paper.”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

“From every source and from all parts of the country come complaints of last season’s packing of apples. The wholesalers denounce the packing of inferior fruit, because it has shut off consumption; the retailers have had grievance for the same reason and the consumer has been so disgusted he has simply passed the apples by and has bought oranges and bananas instead.”

Springdale News, June 15, 1908

“There would be such a line, we would take the truck over and leave it. A man would stay with it to pull it up. And at noon someone would take his place. We’d be lucky if we got it unloaded that day. And this was in the 1930s when the apple business was sort of winding down.”

Jack Yates

Benton County Daily Democrat, March 1, 1987

“As the hundreds of carloads were dispatched . . . Secretary Stroud’s office [of the Ozark Fruit Growers Association] . . . was kept in touch with the market conditions in cities from Denver and St. Paul eastward by representatives and salesmen who quoted prices . . . the refrigerator cars of local fruit were sent to points where there was the greatest demand. . . . Constant communications by wire kept the output of fruit from glutting any particular market, and results were soon evident in better prices to the grower.”

Will Plank

Benton County Pioneer, March 1963

“There is much more to a glass of cider than just squeezing apples so over came Cleva and Harry Douglas [of Rogers] with buckets and baskets, tubs and sacks . . . There were a few discussions with bees and wasps as to just which apples belonged to whom, but I didn’t push the issue, and let them have a fair share.”

Lanette Tillman

Oklahoma Ranch and Farm World, April 13, 1969

“Owing to the extensive apple orchards and the large returns received from the crops, much attention is being paid to methods of care and cultivation . . . as well as packing and marketing the fruit. It has been our observation that the grower who gives his orchard good care and cultivation is repaid many times over for the extra expense.”

Fruit Farming Along the Frisco, 1899

“The [Southern Fruit Products Co.] factory is nearly as large as all out doors. Uses apples of all grades, large and small, and has a capacity of 3,500 bushels per day and even then the bins get to running over though they work night and day. Last year it made 530,000 gallons of vinegar which finds its way to every section of the Union. Sells by the train load. Just think of that, Betsey, train loads of vinegar!”

Martha A. Warren, September 1, 1907

(quoted by Erwin Funk, Rogers Daily News, July 1, 1950)

“The Macon and Carson distillery has up to the present date used something over 30,000 bushels of apples in the manufacture of brandy. They expect before the season is over to use over a quarter of a million bushels of fruit.”

Unknown source, September 1899

(quoted by Robert G. Winn, Washington County Observer, 1970s–1980s)

“The apples were peeled, sliced, then dried by a night crew over wood stoves. Sulphur was thrown on the fires, the resulting vapors preventing the apple slices from turning too brown. When ready to market, the dried apples were sprinkled with soda water and then packed into wooden or pasteboard boxes.”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“The National Pure Food Commission seems to think that the use of sulphur will be a violation of the pure food law. . . . If Sulphur is barred from use in bleaching fruit, it will work great injury to the business and affect not only the evaporator men, but all who grow fruit.”

Springdale News, March 6, 1908

“. . . no commercial apple has even been as well adapted to Northwest Arkansas’s climate and soil as the Ben Davis; and probably no apple will ever be. . . . Said a Louisiana native to an Arkansas apple peddler, ‘That man Benny Davis up there sho’ do grow the apples.'”

Thomas Rothrock

Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Winter 1974

“The awards on apples [at the Chicago World’s Fair] have just been made and the Arkansas display . . . secured the highest award for the largest and best display of apples. . . . New York had long been noted for her apples but they did not begin to compare with the fruit from Arkansas, which was a great revelation to most of the people, who looked upon Arkansas as a wilderness.”

Springdale News, October 30, 1893

Photo Gallery

68-19-1025

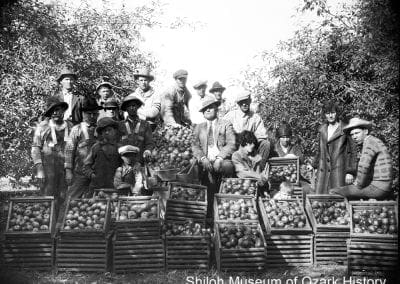

A “bumper crop” of apples, Springdale area, about 1909. Aaron and Speece, photographers. Annabel Searcy Collection (S-68-19-1025)

P-884

Luke L. Kantz kneeling with his apples, Fayetteville, 1900s. John T. Stinson, photographer. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-884)

81-134-2

William B. Brogdon home and orchard, northeast of Springdale, 1910s. Bettylou Boyd Collection (S-81-134-2)

79-4-59

Apple trees in bloom at the Napoleon B. Long orchard, southeast of Springdale, 1900s. Bruce Vaughan Collection (S-79-4-59)

84-34-1-9

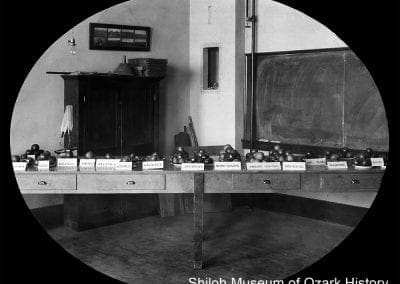

Arkansas Black, Ben Davis, and other apple varieties, probably at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1900s. Dr. Roy C. Rom Collection (S-84-34-1-9)

2010-98

Benjamin F. Smith holding loppers in his orchard near the White River, east of Springdale, 1910s. Harvey Smith Collection (S-2010-98)

88-58-31

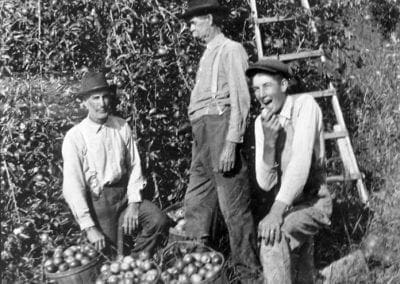

Benjamin F. Johnson (center) in his orchard, south of Fayetteville, 1910s. Anne Prichard Collection (S-88-58-31)

83-250-12

Jeff Gover (center) in his orchard, north of Springdale, 1920s. Ray Watson Collection (S-83-250-12)

2008-1-1

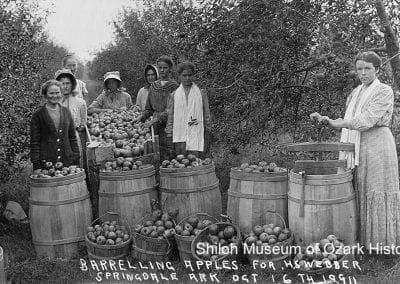

Barreling apples at the H. S. Webber orchard, southeast of Springdale, October 16, 1911. Rogers Historical Museum Collection (S-2008-1-1)

68-19-123

Wagons filled with apples, possibly on the way to the evaporator plant, Springdale, about 1912. Maryman D. Lichlyter, photographer. Annabel Searcy Collection (S-68-19-123)

87-259-19

Loading apples on the Frisco Railroad’s refrigerator cars, Springdale, 1910s. P. J. Smith Jr. Collection (S-87-259-19)

NWAT12-65-18

Making cider at the W. E. Roberts home, Baldwin Community (Washington County), September 23, 1965. John K. Woodruff, photographer. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 12 65-8)

82-209-10

Garrett Williams (left) and Robert Wilson at Williams’ orchard, Buckeye community (Madison County), 1900s. Dorothy Wilson Collection (S-82-209-10)

P-4091

Macon and Carson Distillery, Bentonville, 1900s-1910s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4091)

84-164-31

Processing apples at the A. Edward Rausher farm, Fairmount community (Benton County), 1910s. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-84-164-31)

92-49-45

Frank Ernst’s evaporator, Centerton (Benton County), 1900s. Benton County History Book Collection (S-92-49-45)

82-155-20

Apple Blossom Festival parade float for the Ben Davis apple, First Street, Rogers, 1924. Fadjo Cravens Jr. Collection (S-82-155-20)

Credits

“A. D. Lester Reminisces About Hiwassee and Area History.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Summer 1972).

A. E. Rausher farm photo. Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 13, No. 4 (October 1968).

Allen, Eric. “Booming Era of Big Red Apple Seems Like Yesterday to Former Gentry City Recorder.” Southwest Times Record, February 14,1965.

“Apple Varieties Originated in Washington County.” From a 1913 U.S. Department of Agriculture bulletin, Flashback, Vol. 7, No. 3 (September 1962).

“Apples—Once Key Produce.” (unattributed/undated newspaper article in Shiloh Museum research files).

Banks, Pearl Gipple. “The Early Development of the Apple Industry in Benton County.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 2, No. 5 (July 1957).

“Beat the World—Arkansas Apples Carry off Highest Honors at the World’s Fair.” Springdale News, circa October 30, 1893.

“Big Distillery is Running in Arkansas.” Springfield Daily Leader, September 15,1914.

Black, J. Dickson. “Red Apple Once King of Benton.” (unattributed/undated newspaper article, Shiloh Museum research files).

Black, J. Dickson. “U.S. Weather Bureau Here Sign of Apple’s Importance.” Rogers Democrat, April 11, 1975.

Campbell, W. S. “Rise and Fall of the Apple Empire.” Flashback, Vol. XI, No. 1 (February 1961).

Cherry, Kim. “Apples: A Look Back at a Major Industry.” Northwest Arkansas Times, March 6,1982.

Cordell, Mike. Descendants of William Bennet Brogdon Sr. (1854-1929) and Dee Jackson (1862-1927). Mike Cordell, (unpublished manuscript) 2010.

Dupy, Gerald W. “The Bright Future for Ozarks Apples.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 45, No. 5 (October/November 1997).

“Eight Awards on Fruit.” Arkansas Democrat, October 1893.

“Evaporator Men Meet. Action of Pure Food Commission Causing Some Uneasiness in this Section.” Springdale News, March 6,1908.

Fruit Farming Along the Frisco. St. Louis and San Francisco Railway, St. Louis, MO: 1899.

Funk, Erwin. “Arkansas Was More than Rocky Hillsides.” Rogers Daily News, 7-1-1950.

Funk, Erwin. “Goldsmith Davis and the Ben Davis.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 2, No. 6 (September 1957).

Funk, Erwin. “Red Apple—Deposed King of Ozarks: A Major Regional Industry is Now Almost Extinct.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 2, No. 7 (February 1954).

“Good Packing of Apples—This is Absolutely Necessary in Order to Realize the Best Prices.” Springdale News, June 15,1908.

History of Benton County. Goodspeed, 1889.

Kennedy, Steele T. “Apple Orchards Staging Strong Comeback in Arkansas Ozarks.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 11, No. 10 (November 1963).

“Kimmons, Walker and Co’s. Evaporator.” Springdale News, August 9, 1907.

“Lincoln History Enmeshed in Apples.” (Cherokee Group Apple Festival Section), October 3, 1996.

McColloch, Lacy P. “Apple Industry at Cane Hill, Arkansas.” Flashback, Vol. XVI, No. 4 (November 1966).

McFee, Gladys Brogdon. “Dee Brogdon.” History of Washington County, Arkansas. Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, 1989.

Mores, Jeff. “Apple of the Country’s Eye.” Benton County Daily Record, November 10, 2008.

Neal, Joe. “Arkansas Apple Festival.” Grapevine, October 13, 1976.

Payne, Ruth Holt. “The Seedling that Made Good: The Story of the Black Ben Davis Apple.” Flashback, Vol. IX, No. 1 (February 1959).

“Pictures from Benton County History—A Series.” Benton County Democrat, 4-3-1974.

Plank, Will. “The Ozark Fruit Growers’ Association, Our Great Marketing Organization.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 8, No. 3 (March 1963).

Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World. Random House: New York, 2001.

Reynolds, Sonja. “When Apples Were King—Festivals of Days Gone By.” Benton County Daily Democrat, March 1, 1987.

Rom, Roy C. “Apple Industry.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (accessed May 2019).

Rothrock, Thomas. “A King That Was.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Winter 1974).

Rothrock, Thomas. “King Apple and the Depression—Dust Bowl Years.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Summer 1974).

Rothrock, Thomas. “William Bennett Brogdon: Pioneer Horticulturalist.” Flashback, Vol. 25, No. 3 (August 1975).

“S. B. Van Horn, Practical Ingrafter of Pears and Apples.” Springdale News, 1-17-1908.

Schmitt, Caryn, and Steven Finney. “Life in the Thirties, Washington County.” Flashback, Vol. 36, No. 3 (August 1986).

Sealey, Ross H. “Development of the Parker Nurseries: Good Nurseries the Foundation of the Fruit Industry.” Fayetteville Democrat, June 12, 1922.

“They are Spraying—Apple Growers are Awaking to the Importance of the Work.” Springdale News, April 24, 1908.

“Vanzants Named County Farm Family.” Springdale News, August 19, 1984.

Walker, Ernest. “Story of the Improvement of an Old Apple Orchard in Washington County, Arkansas.” Springdale News, February 21, 1908.

“When the Apple was King.” Springdale News, April 21, 1985.

Winkleman, T. A. “Benton County’s Biggest Apple Year.” Benton County Pioneer, Vol. 7, No. 1 (November 1961).

Winn, Robert G. “Glimpses into the Past.” Washington County Observer (undated).