Putting People to Work

PUTTING PEOPLE TO WORK

Online Exhibit

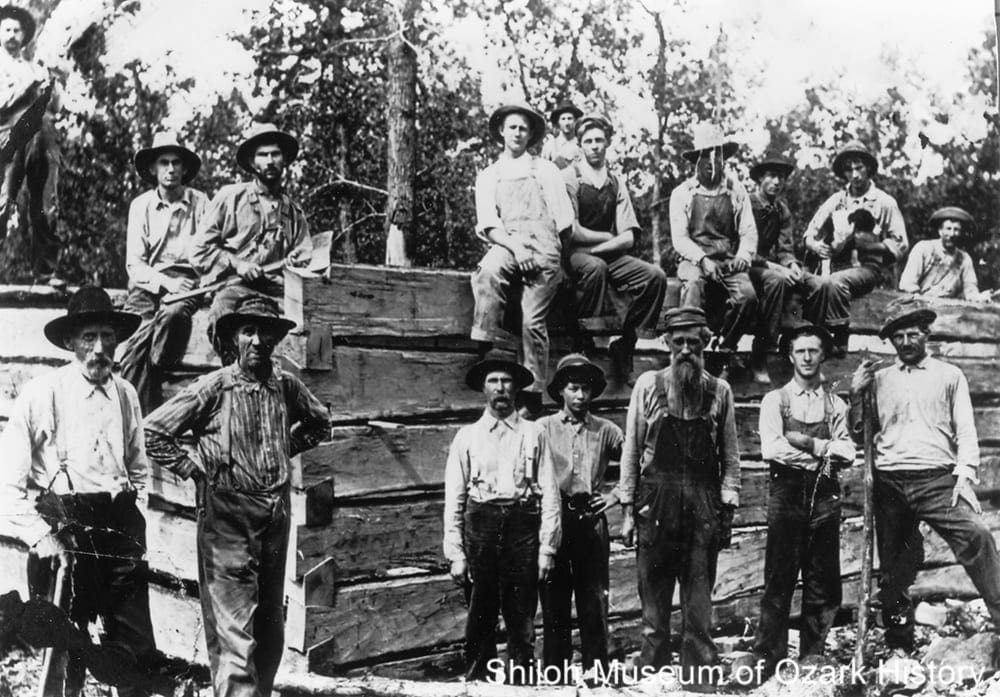

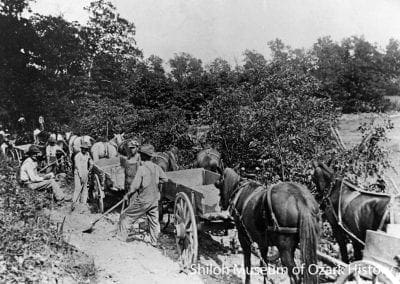

Workers at Devil’s Den State Park, near Winslow (Washington County),1934. Bill Scoggins, photographer. Billye Jean Scoggins Collection (S-95-6-51)

DURING THE 1930s, AMERICA SUFFERED A DEEP ECONOMIC DEPRESSION. Jobs were scarce, banks were unstable and a good part of the nation’s farms were stricken by drought. The people were in despair. Beginning in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the federal government used their powers to improve the lives of Americans. They created a series of experimental economic measures known collectively as the “New Deal.” These measures created jobs for the unemployed, worked towards economic recovery and growth, reformed the financial system, and invested in public works.

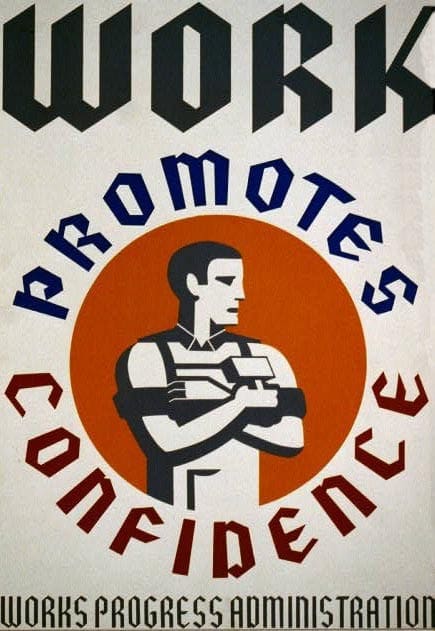

ONE WAY TO HELP WAS TO PROVIDE WORK, RATHER THAN CHARITY. Workers earned income, maintained self-respect and a strong work ethic, and sharpened their work skills. The people of Northwest Arkansas benefited from hundreds of make-work public construction projects, which were administered by a variety of “alphabet agencies” (so called because of the use of initials when referencing their proper names). Agencies provided grants and loans, typically paying for workers’ salaries, while state and local governments supplied the necessary land, materials, and equipment.

Dedication of Bailey Stadium, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, October 9, 1938. With Governor Carl E. Bailey (left) and WPA Administrator Harry Hopkins (speaking). Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-762)

FEDERAL FUNDS WERE USED TO PROVIDE BASIC RELIEF TO PEOPLE IN NEED. In Northwest Arkansas, woodcutters chopped firewood for cooking and heating, visiting housekeepers improved home conditions, and seamstresses made warm comforters. The federal government gave $8,384 towards a program which turned surplus ticking (a tightly woven fabric used for making mattresses) into overalls in Madison, Benton, and Washington Counties. Workers were hired as supervisors at canning kitchens, as research and statistics clerks at the University of Arkansas, and as sanitary workers in the disposal of drought-stricken livestock. As part of the National Youth Administration, Washington County boys built coffins for paupers while Madison County girls made toys. Under the Works Progress Administration, archeological sites were surveyed and pre-historic Native American materials were collected on behalf of the University of Arkansas museum in Fayetteville.

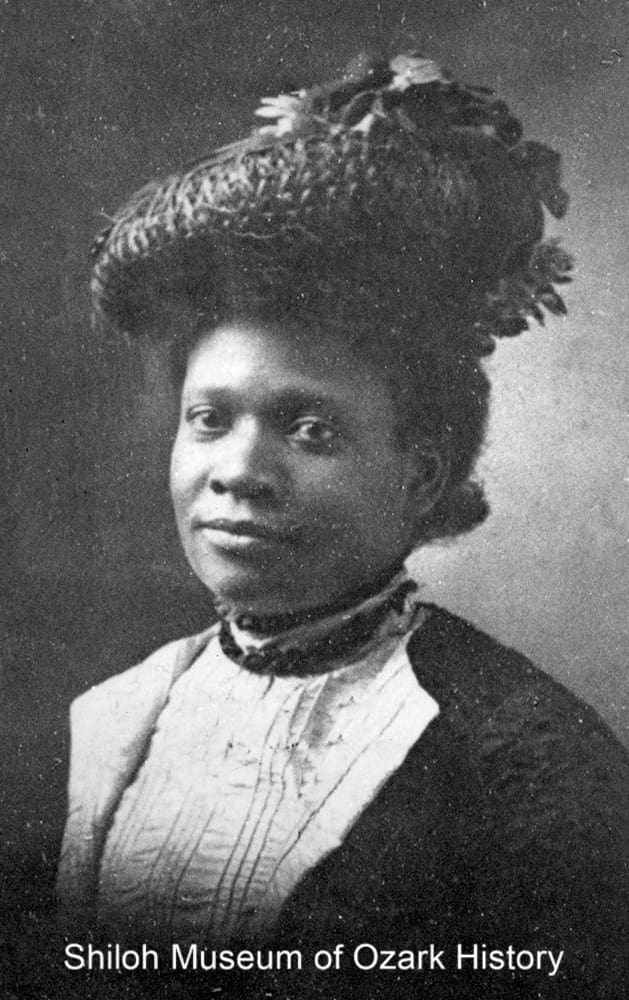

THE WPA OPERATED SEVERAL ARTS- AND CULTURE-RELATED PROJECTS. The Federal Art Project hired artists to paint murals and create sculptures for post offices in Springdale, Siloam Springs, and Berryville. As part of the Federal Writers’ Project, writers contributed to the American Guide Series, producing a guidebook which described Arkansas towns, historical sites, scenic areas, and resources. The Writers’ Project also collected oral histories from early settlers and enslaved African Americans. Workers with the Historical Records Survey in Madison County cataloged public records for use by local citizens and researchers.

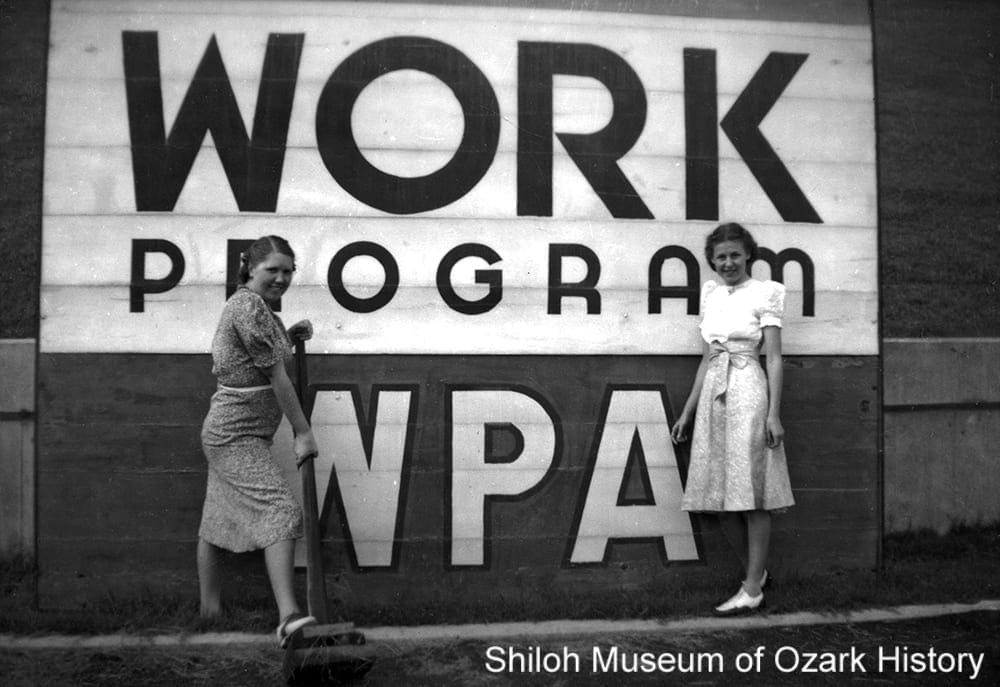

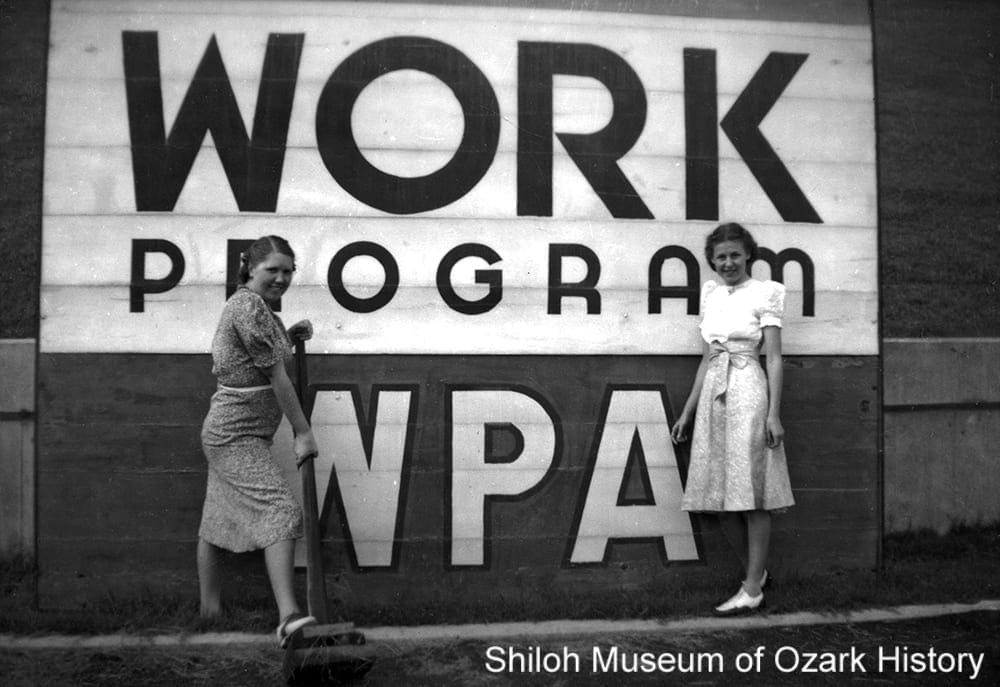

Thelma Blake Lierly (left) and Ruby Burks Warren, Bailey Stadium, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1940. Lloyd O. Warren, photographer. Lloyd O. Warren Collection (S-96-2-533)

NOT EVERYONE AGREED WITH ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL RELIEF EFFORTS. Some claimed that the far-reaching programs were an unconstitutional extension of federal authority. Others said that projects weren’t fairly distributed or that some were of little value. Some felt that projects such as canning food or making mattresses put the government in competition with commercial manufacturers.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION CAME TO AN END WITH WORLD WAR II. New Deal projects were phased out, as men were sent to fight overseas and women entered the workforce. Today, Americans still benefit from New Deal-era programs such as Social Security, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. And in Northwest Arkansas, we still value and enjoy the many parks, roads, schools, and government structures built during a time when it was important to put people to work.

Alphabet Agencies in Northwest Arkansas

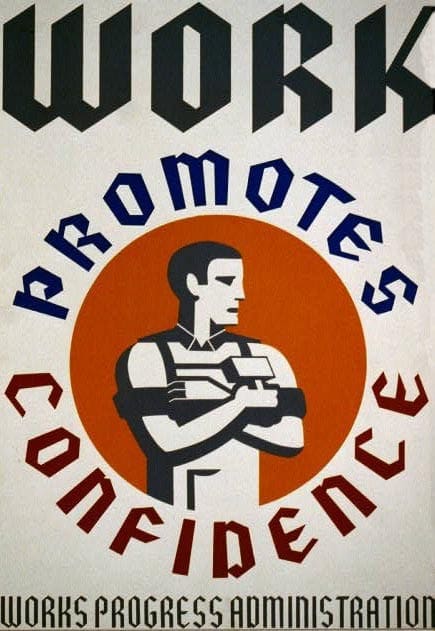

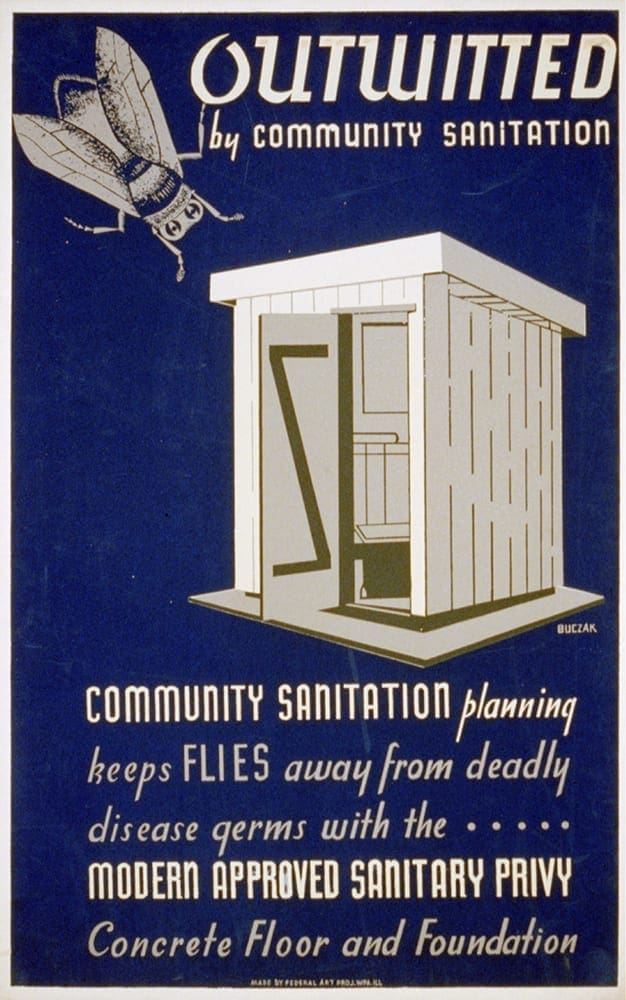

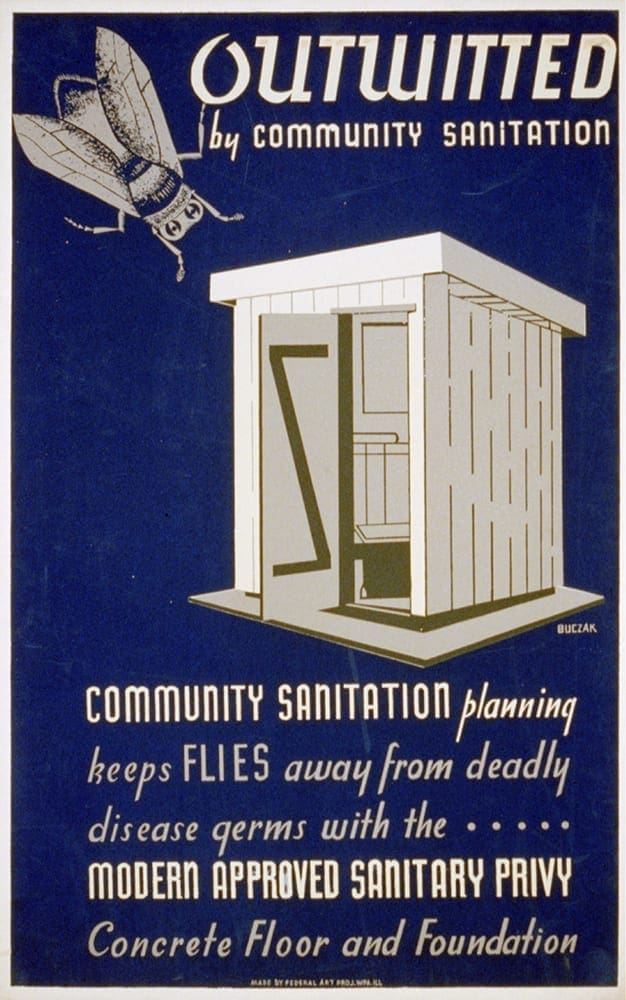

WPA poster, 1940. John Buczak, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

PWA (1933–1943)—The Public Works Administration planned, funded, and administered the building of large public structures such as roads, bridges, dams, post offices, courthouses, schools, and parks. The PWA was a stimulus program. It made loans and grants to state and local governments which in turn hired private construction firms to carry out the work.

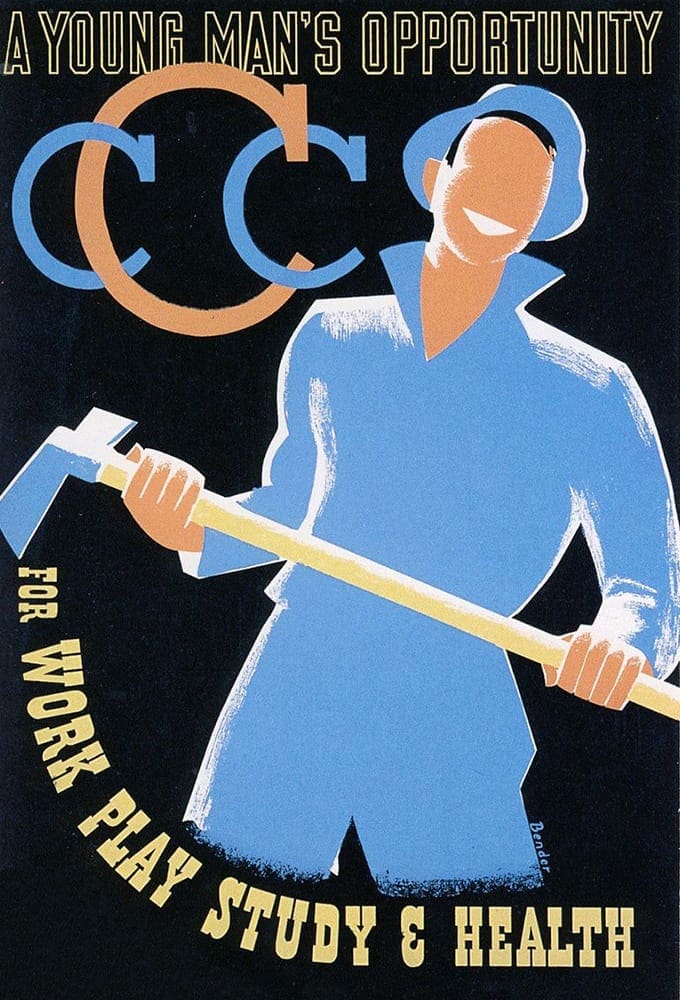

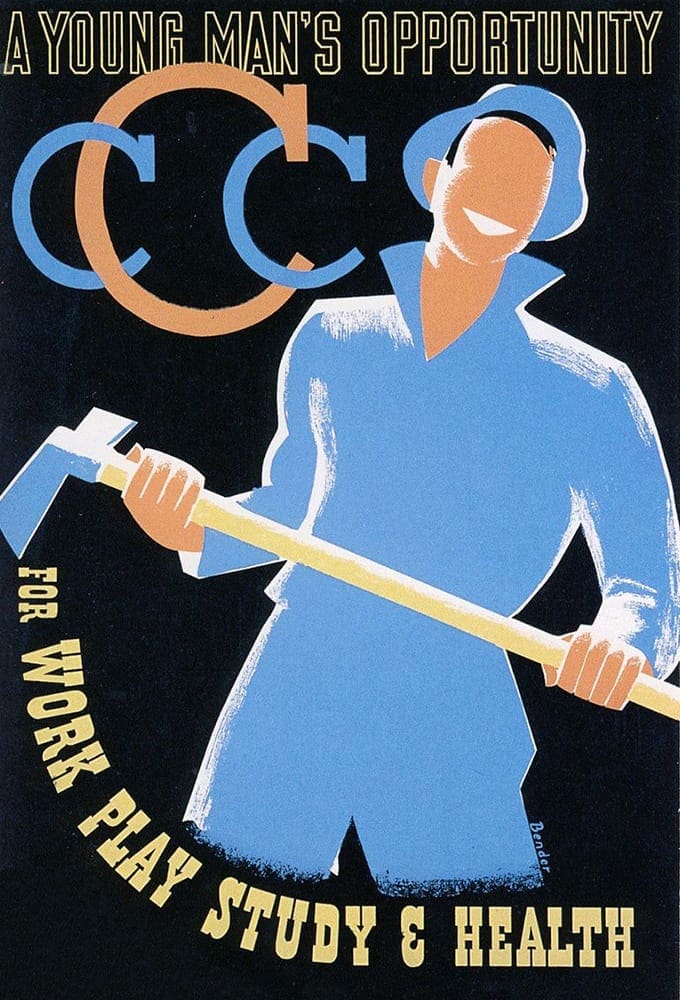

CCC (1933–1942)—The Civilian Conservation Corps conserved and developed natural resources on rural, government-owned lands. The CCC built national and state parks, planted forests, and constructed roads. The program was designed to help single, unemployed, young men whose families were on relief.

FERA (1933–1935)—The Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided funds to states to operate relief programs and create jobs in construction, the arts, and the manufacture of consumer goods. After two years, the FERA was replaced by the WPA.

WPA (1935–1943)—The Works Progress Administration (later renamed the Works Projects Administration) was the New Deal’s largest and most comprehensive agency. Its goal was to provide one paid job for every family in need. The WPA used mostly unskilled laborers to build such things as roads, schools, parks, courthouses, and recreational institutions like museums and zoos.

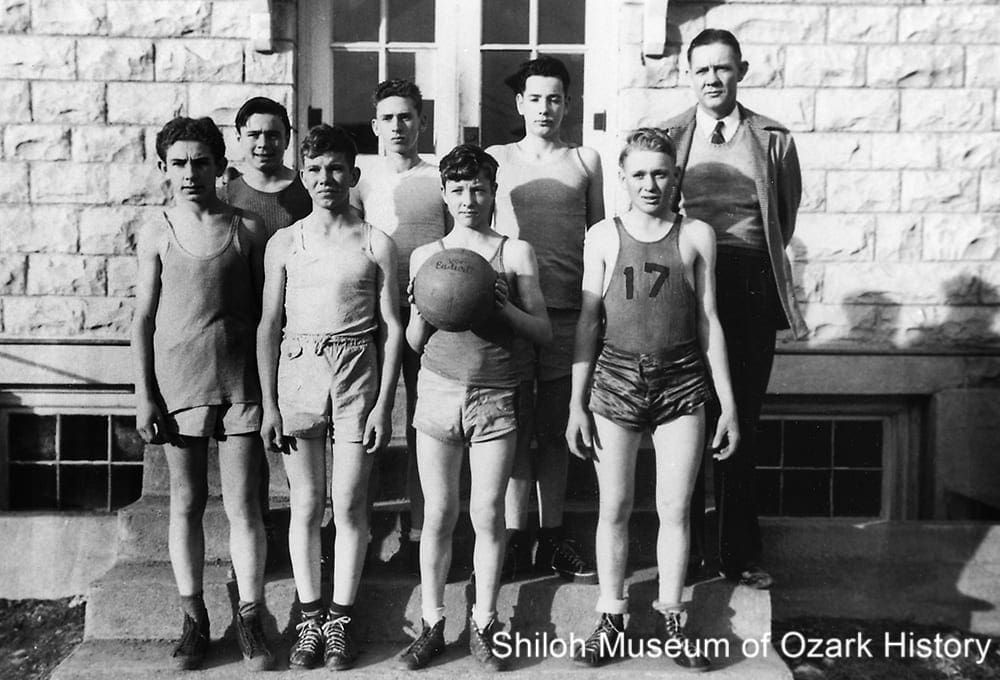

NYA (1935–1943)—The National Youth Administration offered work to youngsters ages of 16 to 25. By employing youth in part-time “work study” jobs at their schools, such as construction, administration, and repair projects, the government hoped to give them skills while keeping them in school and out of the strained job market.

Workers at Devil’s Den State Park, near Winslow (Washington County),1934. Bill Scoggins, photographer. Billye Jean Scoggins Collection (S-95-6-51)

DURING THE 1930s, AMERICA SUFFERED A DEEP ECONOMIC DEPRESSION. Jobs were scarce, banks were unstable, and a good part of the nation’s farms were stricken by drought. The people were in despair. Beginning in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the federal government used their powers to improve the lives of Americans. They created a series of experimental economic measures known collectively as the “New Deal.” These measures created jobs for the unemployed, worked towards economic recovery and growth, reformed the financial system, and invested in public works.

ONE WAY TO HELP WAS TO PROVIDE WORK, RATHER THAN CHARITY. Workers earned income, maintained self-respect and a strong work ethic, and sharpened their work skills. The people of Northwest Arkansas benefited from hundreds of make-work public construction projects, which were administered by a variety of “alphabet agencies” (so called because of the use of initials when referencing their proper names). Agencies provided grants and loans, typically paying for workers’ salaries, while state and local governments supplied the necessary land, materials, and equipment.

Dedication of Bailey Stadium, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, October 9, 1938. With Governor Carl E. Bailey (left) and WPA Administrator Harry Hopkins (speaking). Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-762)

FEDERAL FUNDS WERE USED TO PROVIDE BASIC RELIEF TO PEOPLE IN NEED. In Northwest Arkansas, woodcutters chopped firewood for cooking and heating, visiting housekeepers improved home conditions, and seamstresses made warm comforters. The federal government gave $8,384 towards a program which turned surplus ticking (a tightly woven fabric used for making mattresses) into overalls in Madison, Benton, and Washington Counties. Workers were hired as supervisors at canning kitchens, as research and statistics clerks at the University of Arkansas, and as sanitary workers in the disposal of drought-stricken livestock. As part of the National Youth Administration, Washington County boys built coffins for paupers while Madison County girls made toys. Under the Works Progress Administration, archeological sites were surveyed and pre-historic Native American materials were collected on behalf of the University of Arkansas museum in Fayetteville.

THE WPA OPERATED SEVERAL ARTS- AND CULTURE-RELATED PROJECTS. The Federal Art Project hired artists to paint murals and create sculptures for post offices in Springdale, Siloam Springs, and Berryville. As part of the Federal Writers’ Project, writers contributed to the American Guide Series, producing a guidebook which described Arkansas towns, historical sites, scenic areas, and resources. The Writers’ Project also collected oral histories from early settlers and enslaved African Americans. Workers with the Historical Records Survey in Madison County cataloged public records for use by local citizens and researchers.

Thelma Blake Lierly (left) and Ruby Burks Warren, Bailey Stadium, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1940. Lloyd O. Warren, photographer. Lloyd O. Warren Collection (S-96-2-533)

NOT EVERYONE AGREED WITH ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL RELIEF EFFORTS. Some claimed that the far-reaching programs were an unconstitutional extension of federal authority. Others said that projects weren’t fairly distributed or that some were of little value. Some felt that projects such as canning food or making mattresses put the government in competition with commercial manufacturers.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION CAME TO AN END WITH WORLD WAR II. New Deal projects were phased out, as men were sent to fight overseas and women entered the workforce. Today, Americans still benefit from New Deal-era programs such as Social Security, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. And in Northwest Arkansas, we still value and enjoy the many parks, roads, schools, and government structures built during a time when it was important to put people to work.

Alphabet Agencies in Northwest Arkansas

WPA poster, 1940. John Buczak, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

PWA (1933–1943)—The Public Works Administration planned, funded, and administered the building of large public structures such as roads, bridges, dams, post offices, courthouses, schools, and parks. The PWA was a stimulus program. It made loans and grants to state and local governments which in turn hired private construction firms to carry out the work.

CCC (1933–1942)—The Civilian Conservation Corps conserved and developed natural resources on rural, government-owned lands. The CCC built national and state parks, planted forests, and constructed roads. The program was designed to help single, unemployed, young men whose families were on relief.

FERA (1933–1935)—The Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided funds to states to operate relief programs and create jobs in construction, the arts, and the manufacture of consumer goods. After two years, the FERA was replaced by the WPA.

WPA (1935–1943)—The Works Progress Administration (later renamed the Works Projects Administration) was the New Deal’s largest and most comprehensive agency. Its goal was to provide one paid job for every family in need. The WPA used mostly unskilled laborers to build such things as roads, schools, parks, courthouses, and recreational institutions like museums and zoos.

NYA (1935–1943)—The National Youth Administration offered work to youngsters ages of 16 to 25. By employing youth in part-time “work study” jobs at their schools, such as construction, administration, and repair projects, the government hoped to give them skills while keeping them in school and out of the strained job market.

Building Northwest Arkansas

THE NEW DEAL LEFT A LASTING LEGACY IN NORTHWEST ARKANSAS. It produced hundreds of construction projects, many of which are still in use today. While dozens of new buildings and structures were built, many projects were small in scale, some involving repairs and renovations to existing structures.

In Fayetteville, the FERA helped pay for beautification improvements at the National Cemetery and for the grading of runways and the installation of a wind cone at Drake Field, the municipal airport. In Siloam Springs, stone walkways were built in city parks by the National Youth Administration. Hundreds of “sanitation units” (outhouses) were built throughout the area, including Winslow, Ponca, Boxley, Erbie, Springdale, and Prairie Grove.

NUMEROUS COUNTY ROADS AND STATE HIGHWAYS WERE IMPROVED OR BUILT. Sections of Highway 71 were graded and paved while a stretch of road between West Fork and Devil’s Den (now Arkansas 170) was built. In 1934, 1,000 men from the CCC built 115 miles of a “scenic loop drive” connecting Fayetteville to Mountainburg in the south and to Combs in the east. “Farm-to-market” roads were built in Newton and Washington Counties, connecting rural, agricultural areas to larger market towns.

85-63-7

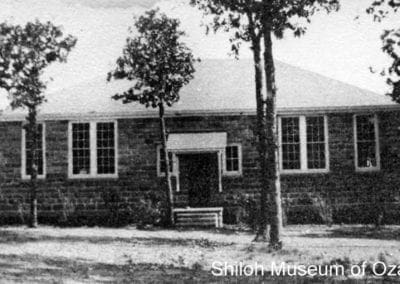

Sulphur Springs High School, Sulphur Springs (Benton County), about 1941. Jim Buckley Family Collection (S-85-63-7)

82-213-12

Little Buffalo River Bridge, Parthenon (Newton County), 1940s. Bob Besom Collection (S-82-213-12)

86-327

Agriculture Building, Huntsville State Vocational School, Huntsville (Madison County), 1939-1940. Wayne Martin Collection (S-86-327)

85-284-34

WPA bridge construction, between Highway 68 and Osage (Carroll County), mid 1930s. Frank Stamps Collection (S-85-284-34)

88-234-83

State Representative A. B. Arbaugh of Newton County speaking at the dedication of the Newton County Courthouse, Jasper, October 26, 1940. Case Studio, photographer. Newton County Times Collection (S-88-234-83)

New Deal Projects in Northwest Arkansas

WPA poster, 1940. John Buczak, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

Below is a partial list of area New Deal projects, with year of completion and the federal agency which helped fund it, if known. Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places are marked with an asterisk [*].

BENTON COUNTY

GARFIELD—Garfield Elementary School* (1942 NYA)

NORWOOD COMMUNITY—Norwood School* (1937 WPA)

ROGERS—Central Ward Elementary School (1936 WPA), Lake Atalanta (1937 WPA)

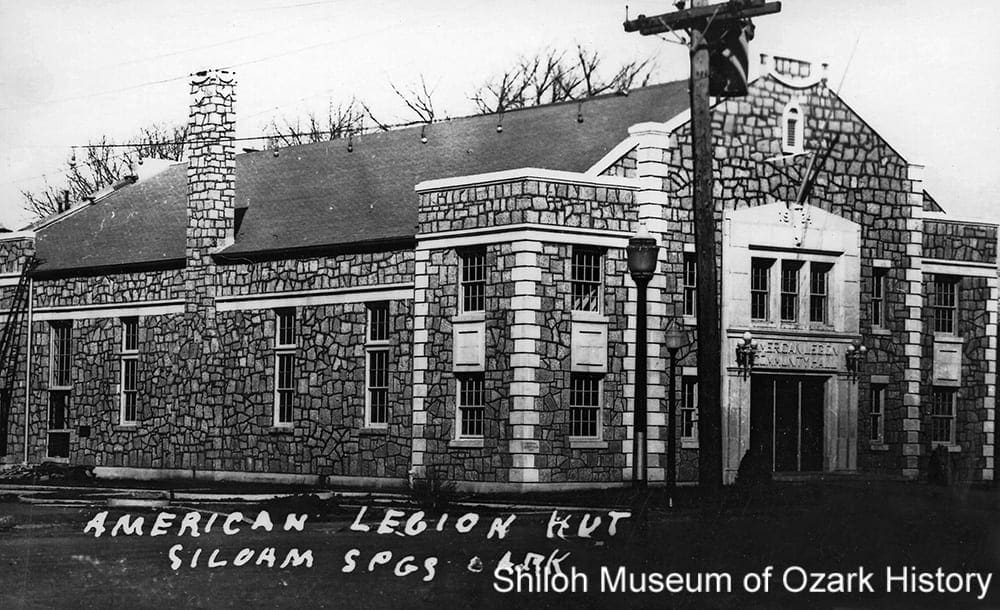

SILOAM SPRINGS—American Legion Hall (1934 WPA), Siloam Springs High School (1940 WPA),

post office* (1937 WPA), Twin Springs fountain (1936 NYA)

SULPHUR SPRINGS—Sewer treatment plant (PWA), Sulphur Springs High School* (1941 WPA)

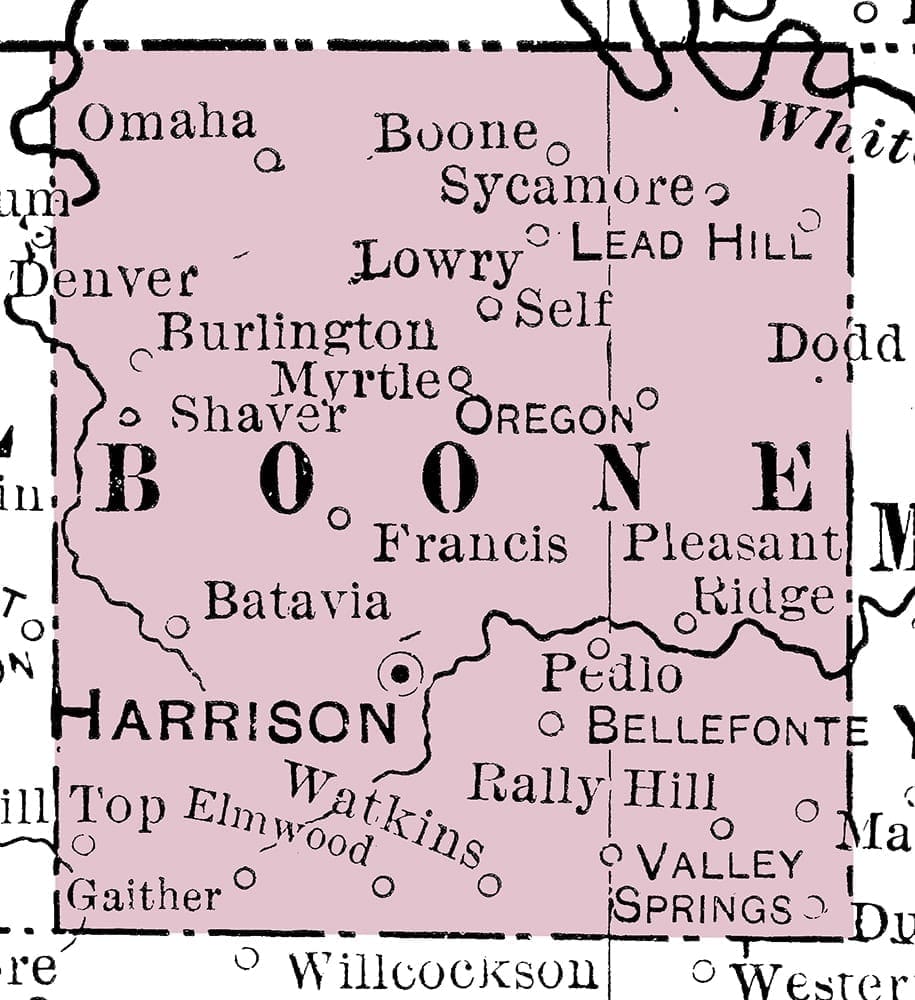

BOONE COUNTY

EVERTON—Everton School* (1939 WPA)

HARRISON—Boy Scout Hut (1938 NYA)

HARRISON AREA—Haggard Ford swinging bridge* (1941 WPA)

VALLEY SPRINGS—Valley Springs School* (1940 WPA)

CARROLL COUNTY

BERRYVILLE—Berryville School Agricultural Building* (1940 WPA) & Gymnasium* (1937 WPA), post office* (1939)

GREEN FOREST—water tower (1937 PWA)

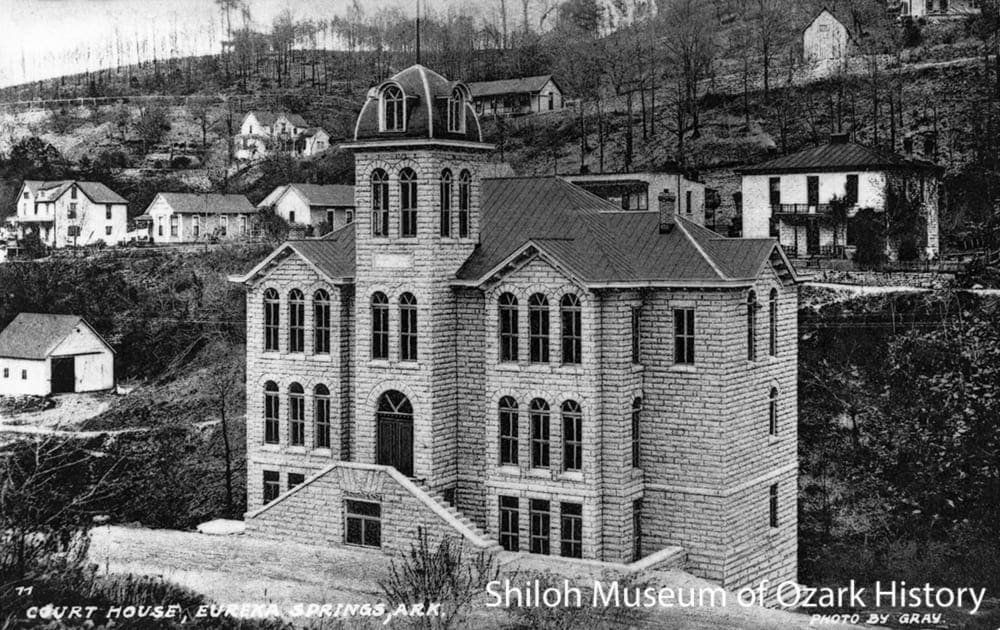

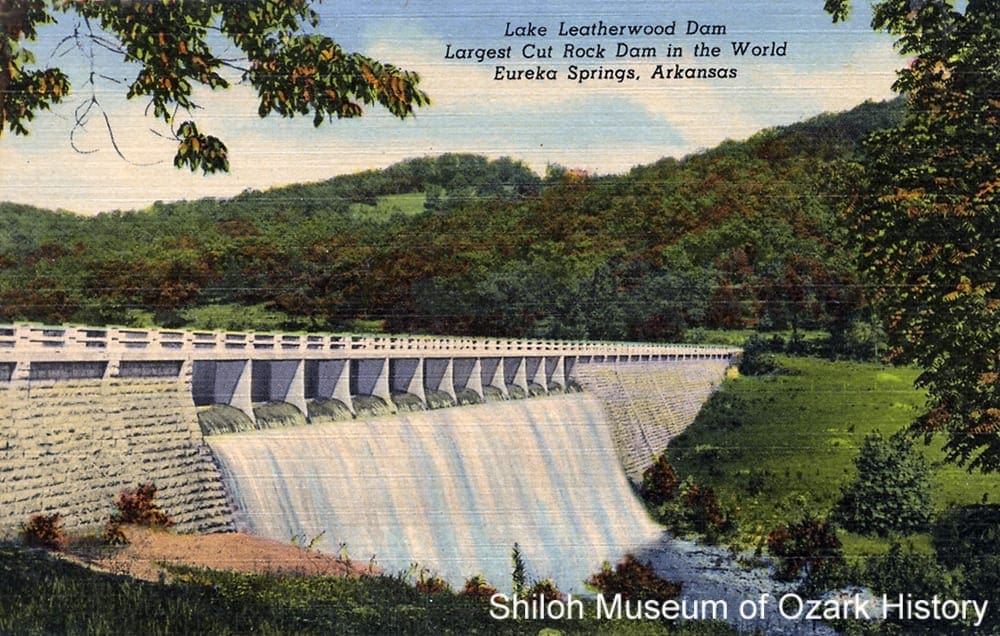

EUREKA SPRINGS—fire station (NYA), Lake Leatherwood* (1939-1940 WPA & CCC), sewage disposal plant (about 1939 PWA)

MULLADAY HOLLOW—bridge* (1935 CCC)

OSAGE COMMUNITY—Osage Elementary School (WPA)

MADISON COUNTY

HINDSVILLE—Hindsville School (1939 WPA)

HUNTSVILLE—paved Huntsville Square (1938 PWA), county courthouse (1939 PWA), Huntsville Grade School & gymnasium (1940 NYA), NYA camp (1939 NYA), Huntsville State Vocational School’s agriculture building (1936 NYA), home economics cottage (1936 WPA), & classroom-gymnasium (1940 NYA)

ST. PAUL—St. Paul High School & gymnasium (1940 WPA & NYA)

THORNEY—Enterprise School* (1935 WPA?)

NEWTON COUNTY

BOXLEY—sanitation units (WPA)

JASPER—county courthouse* (1940 WPA)

LOW GAP—Low Gap School (1939 WPA)

MT. JUDEA—Mt. Judea School (1935 WPA)

PARTHENON—Little Buffalo River Bridge* (1939 WPA), Newton County Academy gymnasium* (1936 WPA)

PONCA—low-water bridge (WPA)

VENDOR—Vendor School (1937 WPA)

WASHINGTON COUNTY

BALDWIN—Rural Women’s Rest Camp (FERA)

EVANSVILLE—Evansville School (1939 WPA)

FAYETTEVILLE—Fayetteville High School’s Root Auditorium-Gymnasium (1939 WPA) & Manual Training School (1939 NYA)

FAYETTEVILLE (UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS)—Agriculture Building (PWA), Band Building (PWA), Bailey Stadium [football & track] (1937 WPA), barn (1935 FERA), Chemistry Building* (1936 PWA), Gibson Hall [men’s dormitory] (1937 PWA), greenhouses, Home Economics Building* (1940 PWA), Field House [men’s gymnasium]* (1937 PWA), Ozark Hall [classrooms]* (1940 PWA), Student Union* (1940 PWA), Vol Walker Hall [library]* (1935 PWA)

LINCOLN—Lincoln Legion Hut (1934 WPA)

PRAIRIE GROVE—jail (FERA), Prairie Grove Legion Hut (1934 WPA), water & sewer systems (1934 FERA)

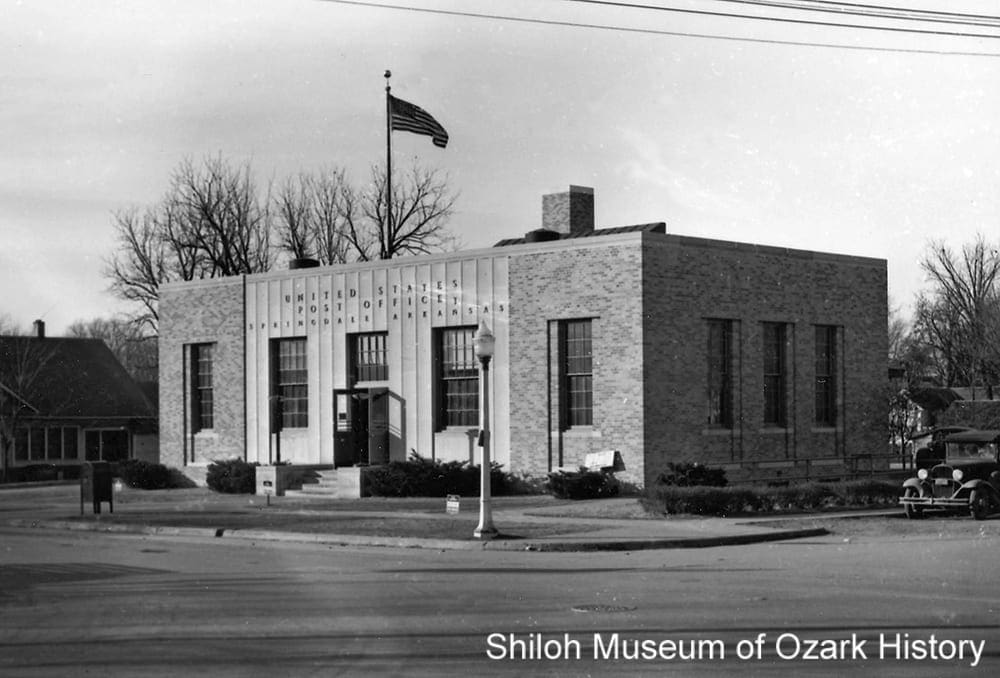

SPRINGDALE—Migrant labor camp (1941 Farm Security Administration), post office (1938 WPA), sanitation units, Springdale Legion Hut* (1934 FERA)

WEDINGTON—Lake Wedington Recreation Area* (1938 Rural Resettlement Administration, Soil Conservation Services, & WPA)

WINSLOW—Devil’s Den State Park* (1934-1942 CCC), Lee Creek bridge (1935 CCC)

New Deal Projects in Northwest Arkansas

WPA poster, 1940. John Buczak, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

Below is a partial list of area New Deal projects, with year of completion and the federal agency which helped fund it, if known. Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places are marked with an asterisk [*].

BENTON COUNTY

GARFIELD—Garfield Elementary School* (1942 NYA)

NORWOOD COMMUNITY—Norwood School* (1937 WPA)

ROGERS—Central Ward Elementary School (1936 WPA), Lake Atalanta (1937 WPA)

SILOAM SPRINGS—American Legion Hall (1934 WPA), Siloam Springs High School (1940 WPA),

post office* (1937 WPA), Twin Springs fountain (1936 NYA)

SULPHUR SPRINGS—Sewer treatment plant (PWA), Sulphur Springs High School* (1941 WPA)

BOONE COUNTY

EVERTON—Everton School* (1939 WPA)

HARRISON—Boy Scout Hut (1938 NYA)

HARRISON AREA—Haggard Ford swinging bridge* (1941 WPA)

VALLEY SPRINGS—Valley Springs School* (1940 WPA)

CARROLL COUNTY

BERRYVILLE—Berryville School Agricultural Building* (1940 WPA) & Gymnasium* (1937 WPA), post office* (1939)

GREEN FOREST—water tower (1937 PWA)

EUREKA SPRINGS—fire station (NYA), Lake Leatherwood* (1939-1940 WPA & CCC), sewage disposal plant (about 1939 PWA)

MULLADAY HOLLOW—bridge* (1935 CCC)

OSAGE COMMUNITY—Osage Elementary School (WPA)

MADISON COUNTY

HINDSVILLE—Hindsville School (1939 WPA)

HUNTSVILLE—paved Huntsville Square (1938 PWA), county courthouse (1939 PWA), Huntsville Grade School & gymnasium (1940 NYA), NYA camp (1939 NYA), Huntsville State Vocational School’s agriculture building (1936 NYA), home economics cottage (1936 WPA), & classroom-gymnasium (1940 NYA)

ST. PAUL—St. Paul High School & gymnasium (1940 WPA & NYA)

THORNEY—Enterprise School* (1935 WPA?)

NEWTON COUNTY

BOXLEY—sanitation units (WPA)

JASPER—county courthouse* (1940 WPA)

LOW GAP—Low Gap School (1939 WPA)

MT. JUDEA—Mt. Judea School (1935 WPA)

PARTHENON—Little Buffalo River Bridge* (1939 WPA), Newton County Academy gymnasium* (1936 WPA)

PONCA—low-water bridge (WPA)

VENDOR—Vendor School (1937 WPA)

WASHINGTON COUNTY

BALDWIN—Rural Women’s Rest Camp (FERA)

EVANSVILLE—Evansville School (1939 WPA)

FAYETTEVILLE—Fayetteville High School’s Root Auditorium-Gymnasium (1939 WPA) & Manual Training School (1939 NYA)

FAYETTEVILLE (UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS)—Agriculture Building (PWA), Band Building (PWA), Bailey Stadium [football & track] (1937 WPA), barn (1935 FERA), Chemistry Building* (1936 PWA), Gibson Hall [men’s dormitory] (1937 PWA), greenhouses, Home Economics Building* (1940 PWA), Field House [men’s gymnasium]* (1937 PWA), Ozark Hall [classrooms]* (1940 PWA), Student Union* (1940 PWA), Vol Walker Hall [library]* (1935 PWA)

LINCOLN—Lincoln Legion Hut (1934 WPA)

PRAIRIE GROVE—jail (FERA), Prairie Grove Legion Hut (1934 WPA), water & sewer systems (1934 FERA)

SPRINGDALE—Migrant labor camp (1941 Farm Security Administration), post office (1938 WPA), sanitation units, Springdale Legion Hut* (1934 FERA)

WEDINGTON—Lake Wedington Recreation Area* (1938 Rural Resettlement Administration, Soil Conservation Services, & WPA)

WINSLOW—Devil’s Den State Park* (1934-1942 CCC), Lee Creek bridge (1935 CCC)

Life in a CCC Camp

THE CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS FOCUSED ON CONSERVING AND DEVELOPING NATURAL RESOURCES. The CCC built state and national parks, planted forests, and constructed roads. The program was designed to help single, unemployed, young men whose families were on relief. The men signed up for six-month stints and could reenlist, up to two years. Workers were fed and given a place to live. They were required to send most of their thirty-dollar-a-month salary back home. For many, the CCC provided valuable job and life skills and a sense of purpose.

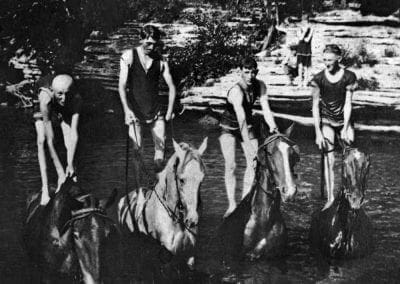

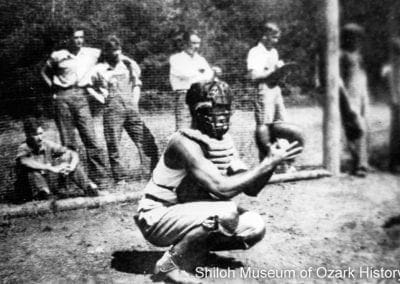

THE LARGEST CCC PROJECT IN NORTHWEST ARKANSAS WAS DEVIL’S DEN STATE PARK NEAR WINSLOW. While the work was overseen by the State Parks Commission, the camp was under the direction of the U.S. Army. The men lived in barracks and followed military discipline. Over 200 men worked there at any one time. From 1933 to 1942 they built roads, bridges, hiking trails, campsites, cabins, furniture, a restaurant, offices, and a stone dam to create Lake Devil. The camp had an educational advisor and library, and offered classes. Recreation included dances, ping pong, swimming, and the Devil’s Den Angels baseball team.

95-6-67

Camp entrance and barracks, Devil’s Den, near Winslow (Washington County), 1934. Bill Scroggins, photographer. Billye Jean Scroggins Bell Collection (S-95-6-67)

85-10-29

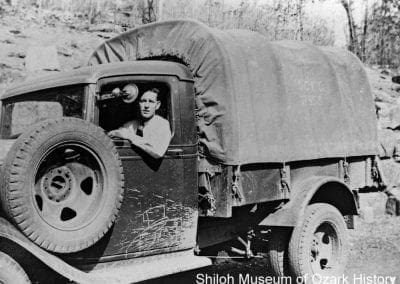

Wardie Hingate driving a truck through the creek to wash it. Devil’s Den State Park Collection (S-85-10-29)

95-6-88

Bulldozer work, 1934. Bill Scroggins, photographer. Billye Jean Scroggins Bell Collection (S-95-6-88)

Memories of Devil's Den

CCC poster, 1941. Albert M.Bender, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

ARTHUR FRIEDMAN—At first [the camp was] filled with men from Minnesota and Wisconsin. I used to see them on the streets of Fayetteville and other towns in Washington County, and we used to do battle with them in the area honkey-tonks. Later on the camps were filled with ‘Arkansawyers’ because it was found that the morale was much better when young men were allowed to serve closer to their home.

HUBERT NICHOLAS—We lived in a barracks. The first one I was in there was about 20 men. When you went into the camp for the first time you went to the “new side.” As people left, to make room for new recruits, you went over to the “other side.” . . . You know times was hard then…a lot of them boys . . . they didn’t have enough to eat.

EDWIN WILSON—The second day some of the older men decided to play a prank on one of the “fresh meats” (as the newcomers were called) and gave him a pail. They told him to go over to the ballpark and milk old Jersey. There was, of course, no cow at the ballpark.

LONNIE CENTER—At first they put us to work cleaning trails and working on the road. We worked on the dam, too. I drove a dump truck, then I worked in the carpentry shop making furniture for the cabins.

RUEBEN S. BLOOD SR.—I think the mule was the only one in our survey crew that didn’t fall down the mountain at least once.

RAY WILKIE—At the camp we got $30 a month plus clothes and board. They sent $25 of that back to our folks. It would make you or break you. Once in a while someone would run, but very few did. There weren’t any jobs to be had.

ED CAUDLE—That $22 was like heaven opening up and sending an abundance of riches those families had never seen before.

JOE COPELAND—I think they tried to choose destitute families to give these benefits to. Of course, that was everybody. . . . I never had a job that amounted to anything before I went to Devil’s Den.

MACK DYER—We learned a lot [about] how to care for ourselves there.

ALVA SPEARS—There was lots of education. I studied surveying and learned to type.

ORVILLE TAYLOR—It’s an important place. As far as I’m concerned, that’s where I got started.

LT. N. H. RANDALL—For well over a year, in freezing weather or scorching sun, [the men] toiled to make the shimmering lake possible. . . . Who knows how long the work of their hands may last?

Memories of Devil's Den

CCC poster, 1941. Albert M.Bender, artist. Work Projects Administration Poster Collection/Library of Congress

ARTHUR FRIEDMAN—At first [the camp was] filled with men from Minnesota and Wisconsin. I used to see them on the streets of Fayetteville and other towns in Washington County, and we used to do battle with them in the area honkey-tonks. Later on the camps were filled with ‘Arkansawyers’ because it was found that the morale was much better when young men were allowed to serve closer to their home.

HUBERT NICHOLAS—We lived in a barracks. The first one I was in there was about 20 men. When you went into the camp for the first time you went to the “new side.” As people left, to make room for new recruits, you went over to the “other side.” . . . You know times was hard then…a lot of them boys . . . they didn’t have enough to eat.

EDWIN WILSON—The second day some of the older men decided to play a prank on one of the “fresh meats” (as the newcomers were called) and gave him a pail. They told him to go over to the ballpark and milk old Jersey. There was, of course, no cow at the ballpark.

LONNIE CENTER—At first they put us to work cleaning trails and working on the road. We worked on the dam, too. I drove a dump truck, then I worked in the carpentry shop making furniture for the cabins.

RUEBEN S. BLOOD SR.—I think the mule was the only one in our survey crew that didn’t fall down the mountain at least once.

RAY WILKIE—At the camp we got $30 a month plus clothes and board. They sent $25 of that back to our folks. It would make you or break you. Once in a while someone would run, but very few did. There weren’t any jobs to be had.

ED CAUDLE—That $22 was like heaven opening up and sending an abundance of riches those families had never seen before.

JOE COPELAND—I think they tried to choose destitute families to give these benefits to. Of course, that was everybody. . . . I never had a job that amounted to anything before I went to Devil’s Den.

MACK DYER—We learned a lot [about] how to care for ourselves there.

ALVA SPEARS—There was lots of education. I studied surveying and learned to type.

ORVILLE TAYLOR—It’s an important place. As far as I’m concerned, that’s where I got started.

LT. N. H. RANDALL—For well over a year, in freezing weather or scorching sun, [the men] toiled to make the shimmering lake possible. . . . Who knows how long the work of their hands may last?

Project Types

Recreation

Workers building a structure, Lake Wedington (Washington County), circa 1937-1938. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-98-85-1745A)

The Lake Wedington Project (1935-1938) was developed to move farmers from worn-out fields to more-productive land, to prevent further soil erosion and to create a scenic recreational and educational area. Hundreds of men were employed, with some coming from as far as Madison County. While most of the workers were paid by the WPA, the project was administered by the Rural Resettlement Administration (and later the Soil Conservation Service), under the direction of Professor C. B. Wiggans of the University of Arkansas Horticulture Department. The 18,000-acre project came to be known as “Wiggan’s Hole.”

With the drought and poor economy, many families in the project area were struggling. Most were glad for the project, which brought much-needed income both in jobs and land sales. Workers built cabins, picnic tables, an administration building, a fire tower, and a dam and 102-acre lake with a diving platform and a bathhouse. They converted farmlands into pastures and planted 350,000 trees and acres of food for wildlife. As the lake filled with water in February 1938, it drew hundreds of wild ducks.

The project boosted the local economy and created the area’s first large recreational lake. Within its first year of operation, it saw over 55,000 visitors and vacationers. Now part of the Ozark National Forest, today the Lake Wedington Recreation Area is managed by the USDA Forest Service. Most of its historic structures remain.

“In discussing the land use plan, [project manager] Wiggans explained that while to the people the recreational features are of prime importance, to the government these are secondary. The government puts first, the desire to preserve, improve and extend the present forest, and second, to develop pastures for grazing that will prevent soil erosion. The government is not unmindful however of the desirability to develop cheap or free recreational facilities and to place them within the reach of the man of small means and his family.”

Northwest Arkansas Times, June 30, 1936

Lake Leatherwood dam, Eureka Springs (Carroll County), 1940s–1950s. Bob Besom Collection (S-83-12-6B)

Lake Leatherwood (1938–1940) near Eureka Springs was built for recreational use and for soil and erosion control, in an effort to protect woodland and possible housing sites at the north end of West Leatherwood Creek. The CCC, WPA, and the Soil Conservation Service came together to build numerous features including barbeque pits, a picnic shelter, roads, a bridge, and a caretaker’s home. The 100-acre lake included a swimming beach, diving platform, bathhouse, and boat dock. The dam was made of concrete and faced with handcut limestone blocks, mined at a nearby quarry. At 1,600 acres, Lake Leatherwood Municipal Park is one of the largest municipal parks in the U.S. In recent years efforts were made to strengthen the dam, bringing it up to modern standards.

Margaret Becker Lester fishing at Lake Atalanta, Rogers (Benton County), early 1950s. Liz Lester Collection

Lake Atalanta (1936–1938) was named for Atalanta Gregory, the late wife of the Rogers businessman who donated the land. Funded by the WPA, the city-owned recreational lake was created by damming Prairie Creek with an earthen dam. Over 100 men were employed daily. In September 1938 WPA officials opened the gates on two springs, allowing the lake to fill. A small dock was built and supplied with city-owned rental boats. The lake was stocked with bass and bream, but anglers had to wait before they could cast a line, to give the fish time to grow. In the late 1940s a recreation complex was built with a swimming pool, restaurant, miniature golf course, and roller skating rink. In recent years Lake Atalanta has undergone a $17.5 million renovation, complete with bike and hiking trails, a dog park, fishing piers, pavilions, a playground, and a wading creek.

“More than 100 men are expected to be given employment on the [Lake Atalanta] project, and many teams of horses will be required. The project is the first approved by the WPA for this area on which farmers, whose crops were affected by the drought, will be given work.”

Springdale News, October 8, 1936

Military

Members of Clarence Beely Post 139 at the American Legion Hut, Springdale, circa 1937. Charles Teeter Collection (S-2007-70-5)

The American Legion is an organization which serves veterans, service members, and communities. During the New Deal four Legion huts were built in Northwest Arkansas, including huts in Prairie Grove and Lincoln. The building of the Springdale hut (1934) was a community affair, with the daily labor rate of $1 paid by the Civil Works Administration (a short-lived job-creation program under the FERA). Many Springdale residents contributed materials and services, including Henderson Scott and his mule team which hauled the stone used to build the structure. The hut served as as a community meeting and polling place for many years. Today it is home to Legion Post 139 and can be rented for events.

American Legion Hut, Siloam Springs (Benton County), 1940s. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-300-61)

The Siloam Springs hut (1934) was built by the WPA and the American Legion. Its walls are of cut stone and cast concrete. By 1990 the building was boarded up and no longer in use. It was later renovated by Main Street Siloam Springs to be used for community and special events. Legion Post 29 still meets there.

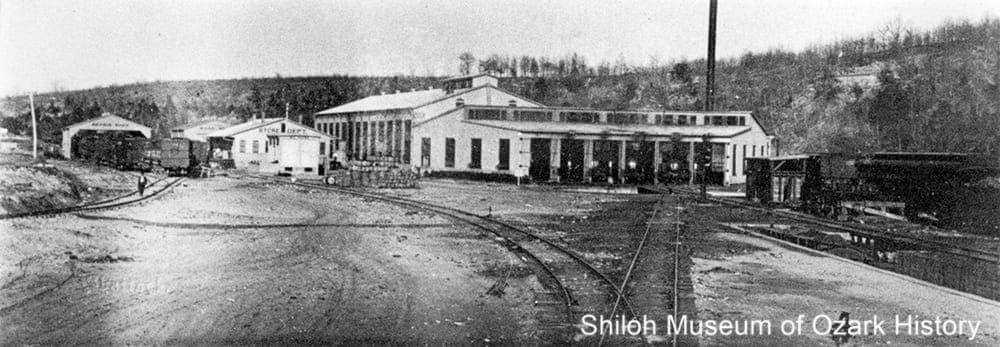

Garage construction, National Guard Armory, Fayetteville (Washington County), circa 1940. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-322A)

The National Guard Armory erected a garage (1940 or 1941) next to its building in Fayetteville, adjacent to the county courthouse. Built of native stone blocks with WPA funds, the building housed the Guard’s vehicles and equipment. Today Washington County uses it to store equipment.

“The [Springdale] hut will serve as a meeting place for members of the post and [women’s] auxiliary as well as a place for public gatherings . . . the hut is the culmination of a hope and desire in the minds and hearts of local ex-servicemen . . . “

Springdale News, August 23, 1934

Transportation

Road builders, Devil’s Den State Park, near Winslow (Washington County), 1935. Carl Smith, photographer. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-2001-103-3)

Miles and miles of roads, streets, and highways were improved or built under the New Deal. A 24-mile-road from Farmington to Oklahoma cost $24,789 while the road between Rhea’s Mill and Cincinnati cost $10,200. Hundreds of men worked on sections of Highway 71, the region’s main artery, improving and grading the roadway. Farm-to-market gravel roads were built in Newton and Washington Counties and elsewhere, connecting farmers in small, rural communities to larger markets. The roads also made it easier for relief supplies like clothing and food to be delivered to distribution points, for pickup by families on assistance.

Paved streets around the town square, Huntsville (Madison County), circa 1940. Julia Outland Collection (S-83-269-6)

The dirt streets surrounding the Huntsville Square (1937–1938) were paved through the WPA and the Arkansas Highway Department, which contributed equipment. Crushed limestone for the streets’ base was quarried nearby and topped with 10,000 gallons of asphalt and a finer layer of crushed limestone.

The WPA helped build bridges in Alpena, Eureka Springs (Mulladay Hollow), Elkins (East First Street), and Parthenon (Little Buffalo River). Just north of Harrison is the Haggard Ford Swinging Bridge (about 1938–1941). WPA-paid workers received $1 a day to build a one-lane suspension bridge over Bear Creek, with poured concrete towers, steel cables and hangers, and a wood deck. A major flood in 1961damaged the bridge, leaving it unable to support vehicular traffic. Further deterioration led to an order to dismantle it in 1977. But local residents rallied to save the bridge, purchasing wood planks and completing the decking work themselves. Today the bridge is open to foot traffic.

“Another loop drive of great scenic beauty between Fayetteville and Mountainburg has been developed within the last year by the Civilian Conservation Corps workers. . . . A thousand young men from the cities have built this road. It is now ready for use, and it will open new territory to almost every motorist . . . “

Springdale News, January 10, 1935

Sanitation Units

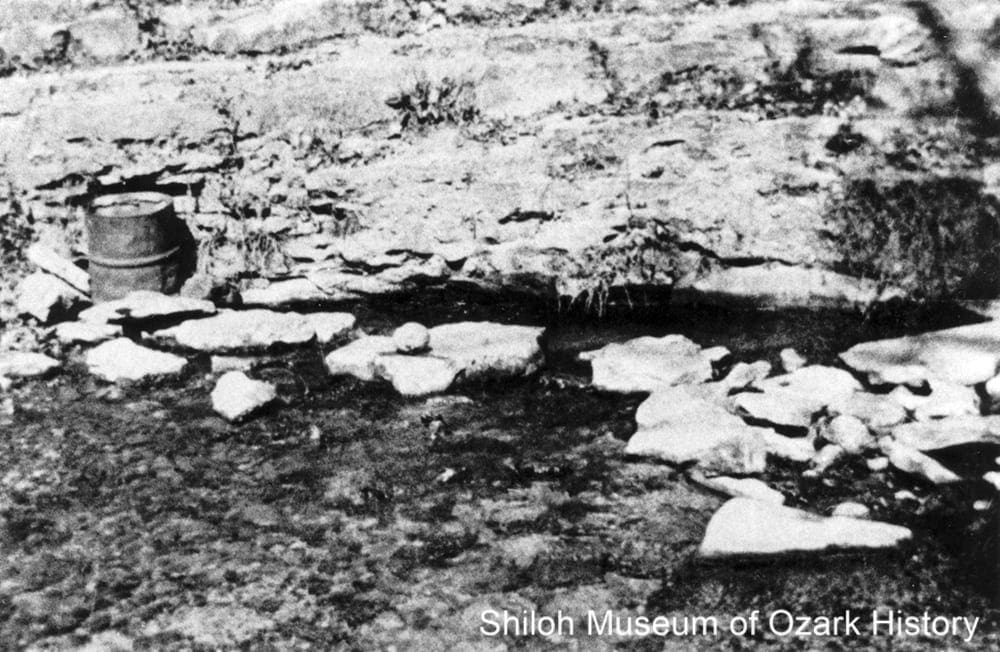

Outhouse at James A. “Beaver Jim” Villines’ farmstead, Boxley Valley, Buffalo National River (Newton County), October 2015. Courtesy National Park Service.

Nearly 54,000 sanitation units (outhouses) were installed in Arkansas by various New Deal agencies. They were built to combat the spread of diseases like hookworm, dysentery, and typhoid fever. By building outhouses in quantity, not only was a whole community better protected, but the bulk purchase of supplies lowered costs. The units were made of wood or stone, ideally with concrete floors. They were designed to be well ventilated and to keep out flies, and located carefully, to prevent groundwater contamination.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration allotted $5,160 to build sanitation units in Washington County, including some in Winslow, Prairie Grove, and Springdale. By May 1935 some 505 had been built. Units were also installed in Boxley Valley, including one built by the Works Progress Administration at James A. Villines’ place. A “one-holer,” it was built of wood with a concrete floor and seat.

“I had one of these [government privies] on the farm that I owned at Erbie [Newton County]. . . . they were designed by a non-imaginative bureaucrat in Washington. The only improvement over the old ones was the hole lined with a burlap sack which was sprayed with used motor oil. This was supposed to keep down flies and wasps. Local builders were given the contract to build these with the stipulation that local, needy labor be used.”

Unknown author, Harrison Times, June 4, 1981

Government

Construction of the Madison County Courthouse, Huntsville, 1939. Gloria Sisk Collection (S-85-296-46)

Two New Deal county courthouses were built in Northwest Arkansas. The Newton County Courthouse (1939–1940) in Jasper was built with WPA labor at a total cost of about $42,000, with the county contributing over $12,000 through a bond issue. The two-story reinforced-concrete-and-granite building was built in a “restrained” Art Deco style, with a rough, native-stone appearance.

The Madison County Courthouse (1939) was built by the PWA in the Art Deco style, with glazed brick, limestone details, and interior marble floors. It held offices, a jail, and a courtroom. The government provided 45% towards the construction cost of $89,000, with the county funding the rest through a narrowly approved bond issue. In 2013 and 2014, voters were once again asked to support the courthouse, by approving a 1% county sales tax to repair the aging structure. They shot down the proposal both times. Some repairs have been made through state funds, but a complete restoration is estimated at $3.6 million.

U.S. Post Office, Springdale (Washington County), 1944. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2002-72-355)

Post offices were built in Berryville (1938–1939), Siloam Springs (1937), and Springdale (1936–1937). The latter was built of ivory-colored brick for $65,000 with WPA funds. It had offices, lock boxes, a mail-sorting room, a basement with employee lockers, and places for patrons to buy stamps, mail packages, and purchase money orders. When the building was dedicated September 1937, there was a parade, concert music, prayers, and speeches by city and post office officials. The building is now home to the Springdale Chamber of Commerce.

Education

Spring Valley School students, Spring Valley (Washington County), 1935. Shirley Dold Collection (S-89-92-45)

Many area elementary and high schools were built as part of the New Deal, including schools in Vendor and Mt. Judea (Newton County), Everton and Valley Springs (Boone County), Berryville (Carroll County), Evansville (Washington County), and Rogers and Sulphur Springs (Benton County). Spring Valley School (Washington County; built about 1935) is a one-story fieldstone masonry building with two detached, rock-veneer sanitary units (outhouses). The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) put $800 towards its construction, with the community supplying the rest.

Parade float at Garfield School, Garfield (Benton County), 1955. Black’s Studio, photographer. David Quin Collection (S-94-173-1)

Garfield Elementary School (1938–1941) was built in the heavy Rustic Revival style popular among Ozark schools. The National Youth Administration paid area youngsters to quarry the building’s limestone from a nearby farm, build a blacksmith shop to keep the quarry’s drill bits sharp, level the building site, and dig the foundation. The boys worked eight-hour days, five days a week for two weeks, earning $14.40. Two weeks off and they were back to work.

Greenhouse, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1956. Howard Clark, photographer. Caroline Price Clark Collection (S-2001-82-354)

The University of Arkansas grew during the New Deal, receiving over $2 million in loans and grants. In 1935 the FERA allotted $2,965 to pay for twenty-six men to build two greenhouses. Public Works Administration-built buildings include the chemistry, agriculture, and home economics buildings, the student union (now Memorial Hall), the field house (formerly the men’s gymnasium and now the Faulkner Performing Arts Center), Gibson Hall (dormitory), a classroom building (now Ozark Hall), and Vol Walker Library (1935), a Classical Revival-style building. Today Vol Walker is home to the Fay Jones School of Architecture.

Vol Walker Library, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1940s. Vaughan-Applegate Collection (S-78-30-2427)

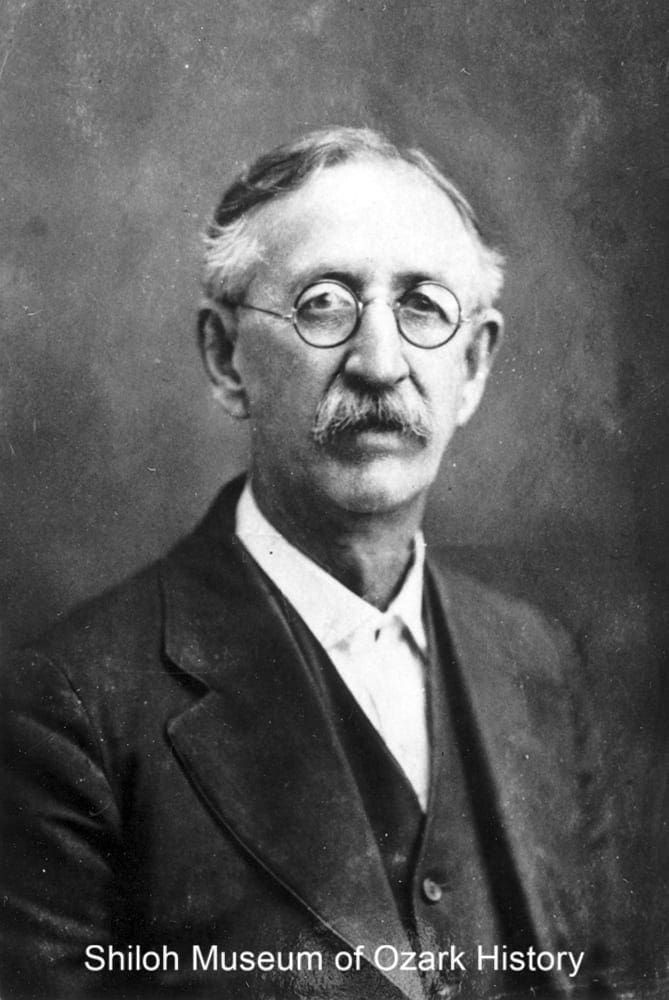

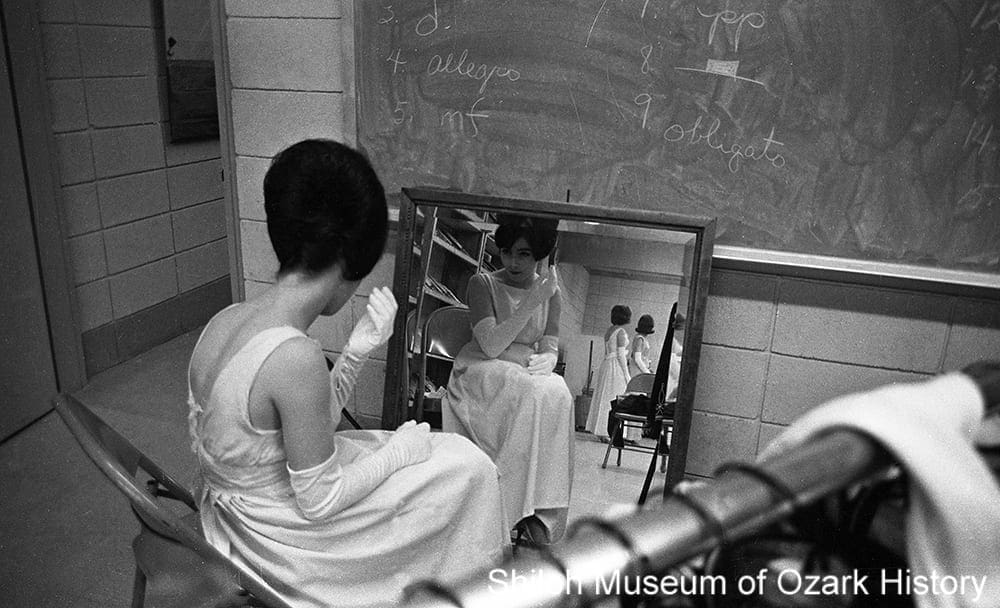

Bailey Stadium (1937–1938) was named after Arkansas Governor Carl E. Bailey. It was a $200,000 Works Progress Administration (WPA) project featuring a track and football field, steel bleachers with wood decking to seat 12,500, a press box, and buildings for equipment and teams. It was noted that “. . . the field proper has been sodded for some time and daily watering has kept it looking green and begging for cleated hoofs.” The stadium was dedicated by WPA administrator Harry Hopkins on October 9, 1938, amid a fanfare of speeches, music, and a procession of University officials, college deans, and ROTC cadets. The name changed to Razorback Stadium after Bailey lost the 1940 election. Over the years the stadium received numerous expansions and renovations. Nothing of the original structure remains.

Bailey Stadium, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, about 1940. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-112)

“The new stadium, which is giving new students and old ones, too, a thrill this week, as they view it for the first time, is something of which any city, any state, any nation could be proud. It ranks with the best. It is built for the ages.”

Northwest Arkansas Times, September 8, 1938

Credits

Arkansas Democrat. “Crowd of 3,000 Attends Dedication Newton County Courthouse at Jasper.” 10-27-1940.

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. “Garfield Elementary School”. http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/national-register-listings/garfield-elementary-school (accessed 9-28-2020).

———. “Beely-Johnson American Legion Post 139.” http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/national-register-listings/beely-johnson-american-legion-post-139 (accessed 9-28-2020).

———. “Madison County Courthouse.” http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/national-register-listings/madison-county-courthouse (accessed 9-28-2020).

———. “Newton County Courthouse.” http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/National-Register-Listings/PDF/NW0005.nr.pdf (accessed 9-28-2020).

Arkansasmatters.com. “Jail Improvement Sales Tax Rejected in Madison County.” 7-2014. https://www.kark.com/news/jail-improvement-sales-tax-rejected-in-madison-county/ (accessed 9-28-2020).

Bernet, Brenda. “Madison County tax proposed for repairs: Courhouse ailing, voters weigh 1% bump.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 9-9-2013.

———. “Old courthouse showing its age: tax seen as way to restore it.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 7-20-2014.

Bowden, Bill. “2 recall time in camp that built Devil’s Den.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 3-18-2013.

Brotherton, Velda. “Boys became men when the joined Civilian Conservation.” White River Valley News, 7-19-2007.

———. “Heritage week celebrations at Devil’s Den honor CCC.” Washington County Observer, 5-5-1994.

———. “When boys from the boonies came to Devil’s Den for employment.” Washington County Observer, 8-30-1990.

———. “Who in the devil built Devil’s Den? How CCC changed lives of locals.” Washington County Observer, 8-9-1990.

Edmisten, Bob. “Building of City Legion Hut Is Success Story.” Springdale News, 3-20-1969.

Fayetteville Daily Democrat. “500,000 E.R.A. Works Program On In County.” 5-9-1935.

———. “WPA Allotment to This Section.” 9-16-1935.

Friedman, Arthur. “Memories of the CCC.” Washington County Observer, 3-3-1988.

Harrison Times. “Along James Lane.” 6-4-1981.

Hatfield, Kevin. A Chronological History of Huntsville, Arkansas. Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society: Huntsville, 2013.

Hope, Holly. An Ambition to be Preferred: New Deal Recovery Efforts and Architecture in Arkansas, 1933-1943. Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, 2006. http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/News-and-Events/publications (accessed 9-28-2020).

Jines, Billie. Benton County Schools That Were, Volume 2. Pea Ridge, Arkansas: self-published, 1993.

Living New Deal. “Haggard Ford Swinging Bridge.” http://livingnewdeal.org/projects/haggard-ford-swinging-bridge-harrison-ar/ (accessed 9-28-2020).

———. “New Deal Programs.” http://livingnewdeal.org/what-was-the-new-deal/programs/ (accessed 9-28-2020).

McGimsey, C. R. “Importance of UA Museum Stressed.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 6-30-1970.

McGlumphy, Veronica. “‘Wiggans’ Hole:’ History of Lake Wedington.” Flashback, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Spring 2008).

Moss, Teresa. “Lake Atalanta to get makeover.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 7-23-2015.

Neal, Lisa. “CCC Company Celebrates 50th at Devil’s Den.” Springdale News, 1-26-1983.

Newton County Times. “Historic courthouse at center of festival.” (with excerpt of an article by Kay Bona, [Little Rock] Daily Record). 6-26-2003.

Northwest Arkansas Times. “Add 124 Men to RRA Project.” 3-11-1936.

———. “PWA Inspector Opens Office.” 1-4-1939.

———. “Students Find Campus Change: Construction Work on Natural Bowl Thrills U. of A. Group.” 9-8-1938.

———. “University Stadium.” 9-8-1938.

———. “Wedington Lake Filled.” 2-18-1938.

———.”Lake Wedington Facility to Be Retained.” 7-7-1939.

Rushing, Parker. “Civilian Conservation Corps workers recall the old days at Devil’s Den: They got good deal from ‘New Deal.'” Washington County Observer, 7-6-1989.

Smith, Charlotte Ann Blood. “My Daddy Made a Difference: Daughter Remembers Lt. Col. Reuben S. Blood, Builder of Devil’s Den and Petit Jean Parks.” Ozarks Mountaineer, Vol. 56, No. 5 (Sep/Oct 2008).

Springdale News. “Hopkins to Dedicate New U. of A. Stadium.” 8-25-1938.

———. “New Home of Post Office is Modern Building.” 4-29-1937.

———. “Rogers’ Lake Atalanta to Open September 19.” 9-8-1938.

———. “Rogers Lake Project Approved Last Week.” 10-8-1936.

Steed, Stephen. “Creators of Devil’s Den meet to recall the past.” Arkansas Gazette, 7-2-1989.

Sugg, Ann Wiggans. “Memories of Lake Wedington.” Flashback, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Spring 2008).

Tisdale, E. H., and C. H. Atkins. “The Sanitary Privy and Its Relation to Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 33 (November 1943). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1527454/ (accessed 9-28-2020).

Tucker, Tammy. “Plight of Lake Leatherwood.” (Springdale) Morning News of Northwest Arkansas,” 6-4-2000.

U.S. Treasury Department, Public Health Service. The Sanitary Privy, Government Printing House: Washington D. C., 1933. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/300287 (accessed 9-28-2020).

University of Arkansas. “Faulkner Performing Arts Center.” https://faulkner.uark.edu/about/index.php (accessed 9-28-2020).

Walker, Leeanna. “Lake Atalanta a Rogers getaway since 1937.” [Rogers] Northwest Arkansas Morning News, 5-25-1986.

Whitaker, Rachel. “In Search of an Outhouse.” The Backstay, 9-8-2015.

Whittemore, Carol. “Madison County Courthouse Marks Its 50th Anniversary.” Madison County Record, 11-23-1989.

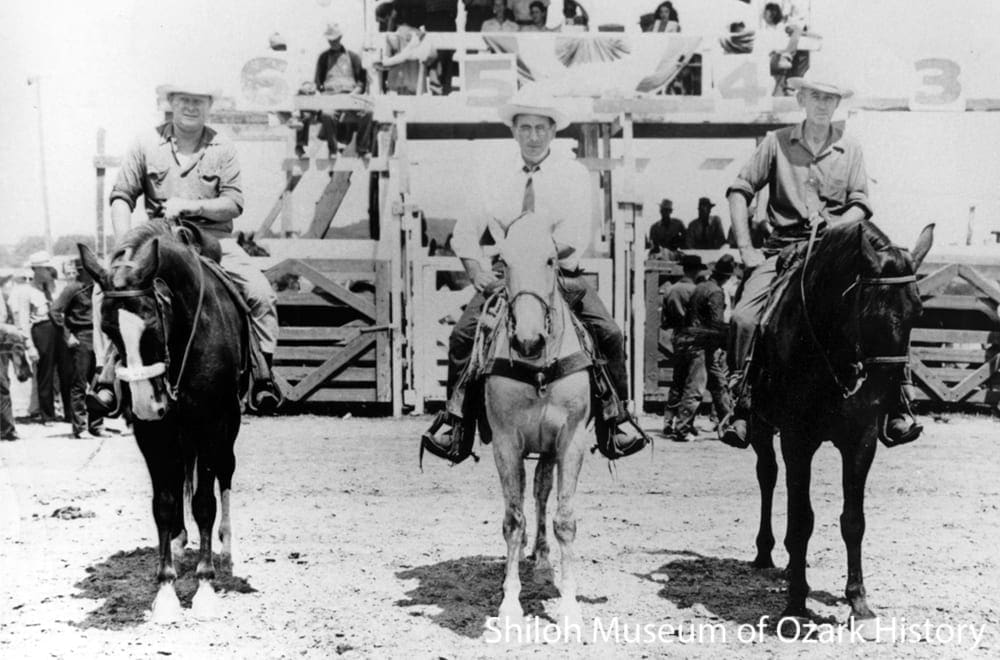

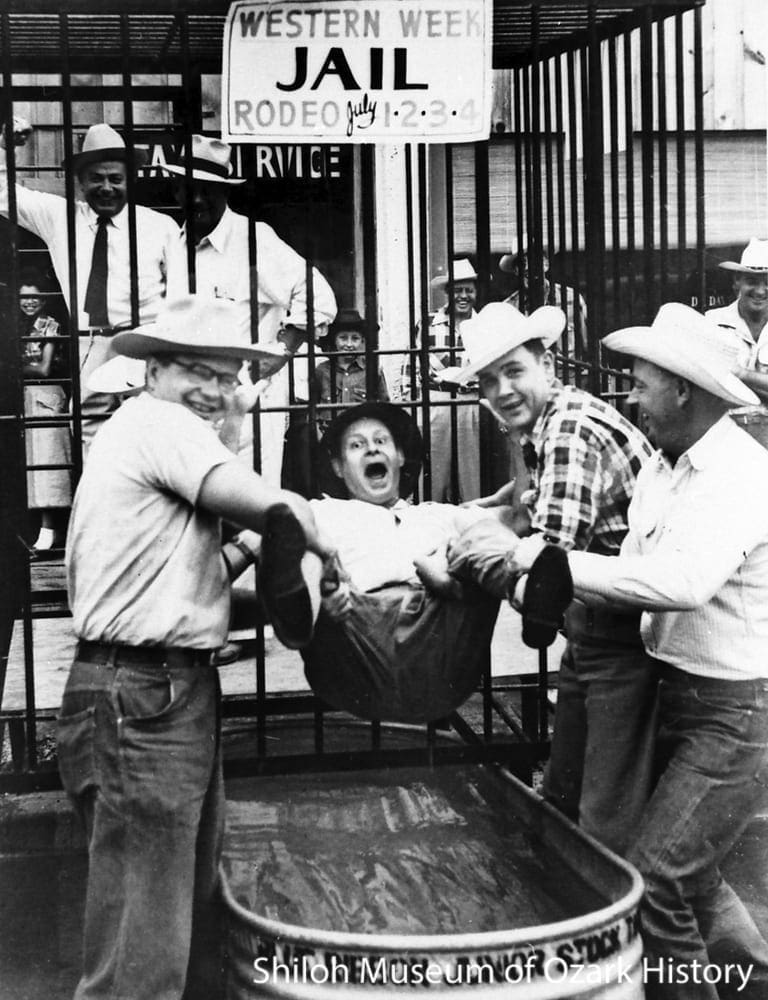

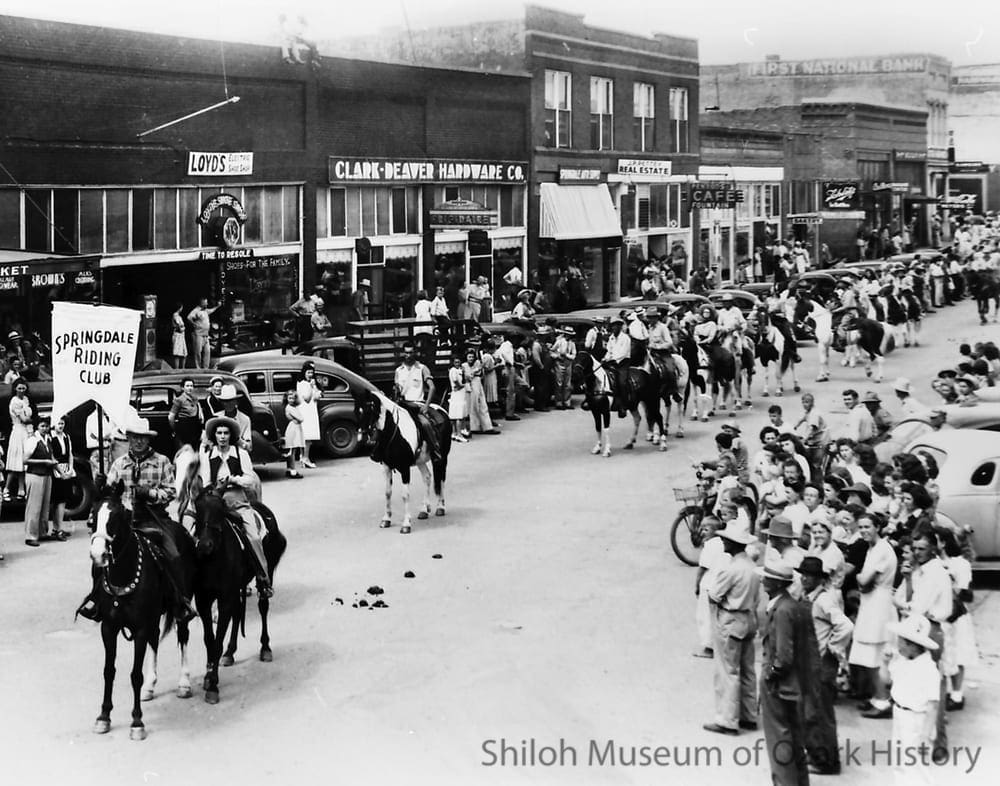

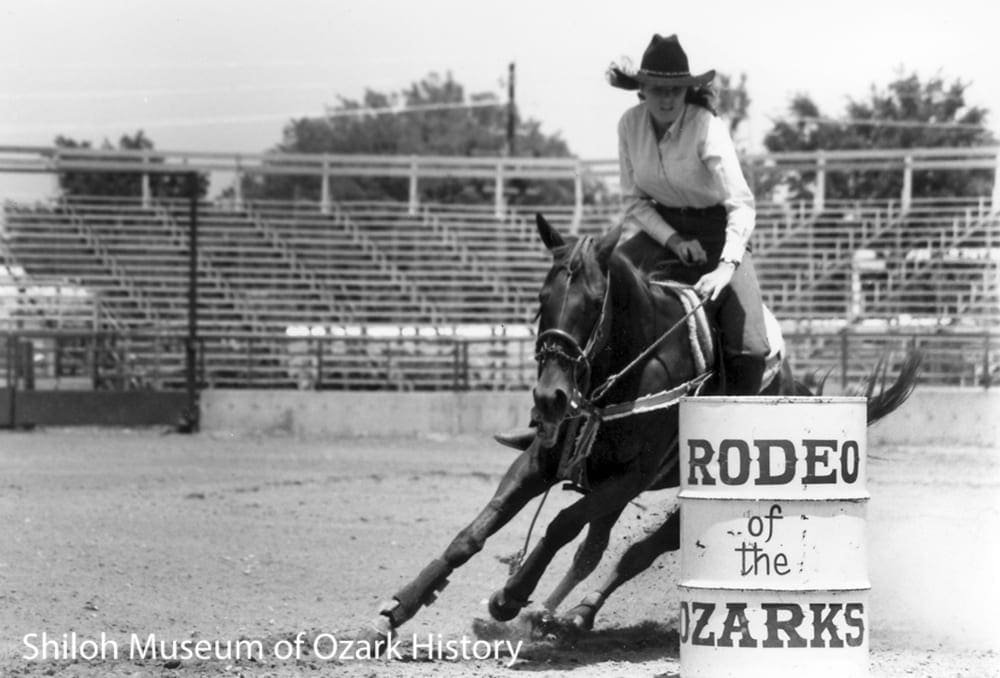

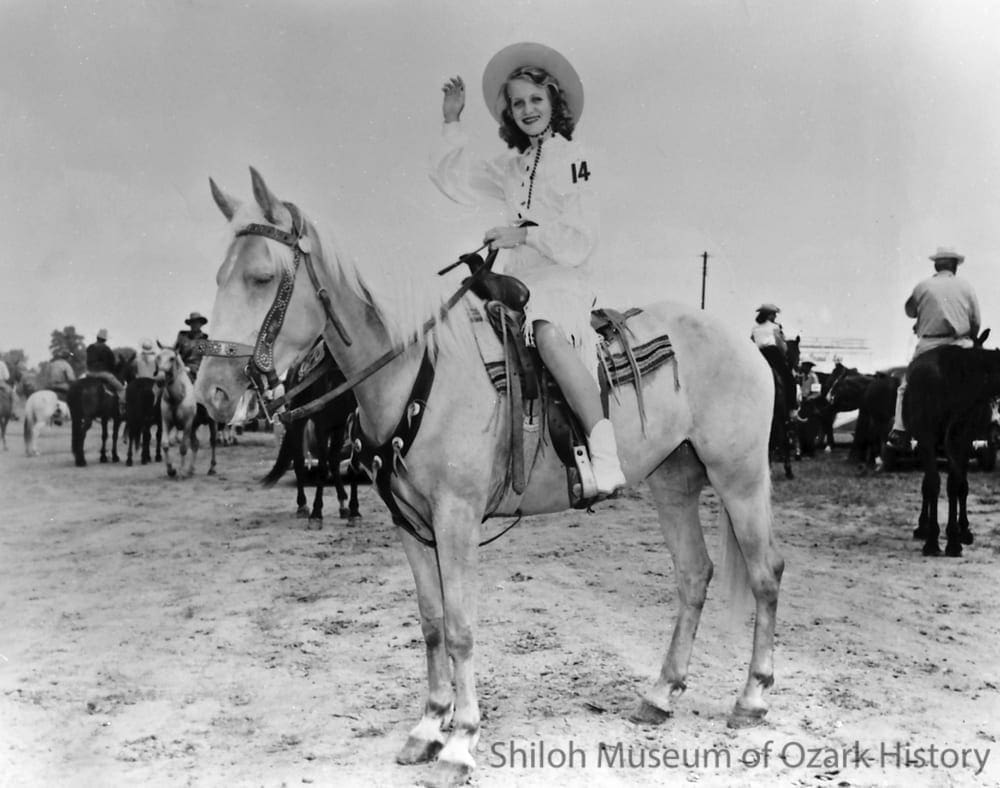

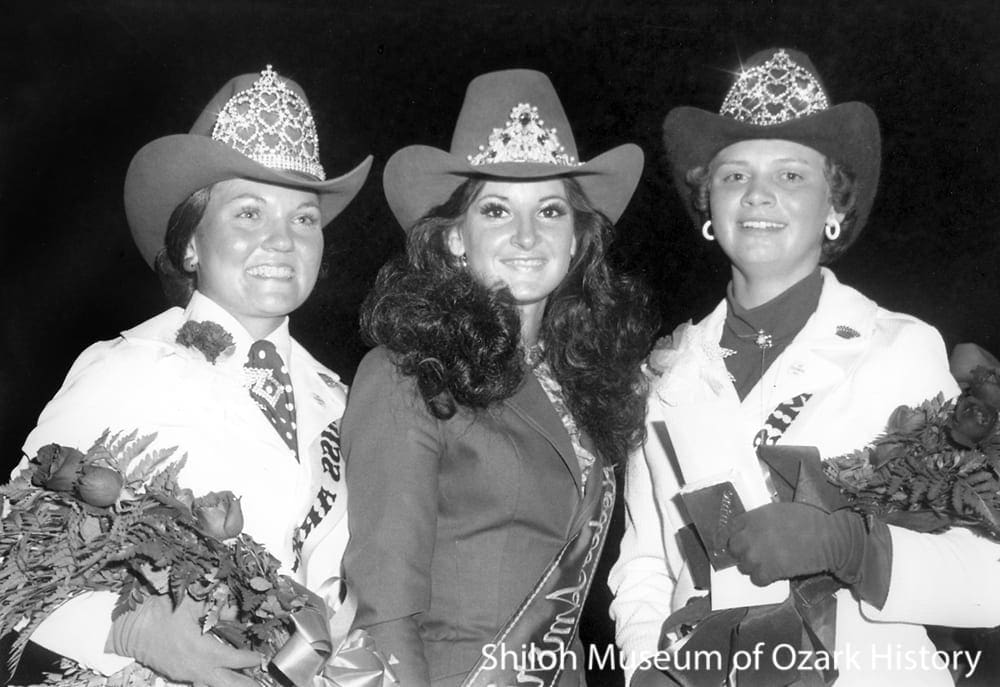

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.