Scenes of Carroll County

Online Exhibit19th Century Settlement

For a time the area now called Carroll County was the hunting grounds for the Osage. But they were forced out as white settlement in the East began pushing other Native American groups west. In 1838 about 16,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes, moving through Arkansas to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) along the “Trail of Tears.” Some 1,200 Cherokees and enslaved people followed the Benge Route through Carroll County, from Osage and Carrollton in the east down to Huntsville (Madison County) and beyond.

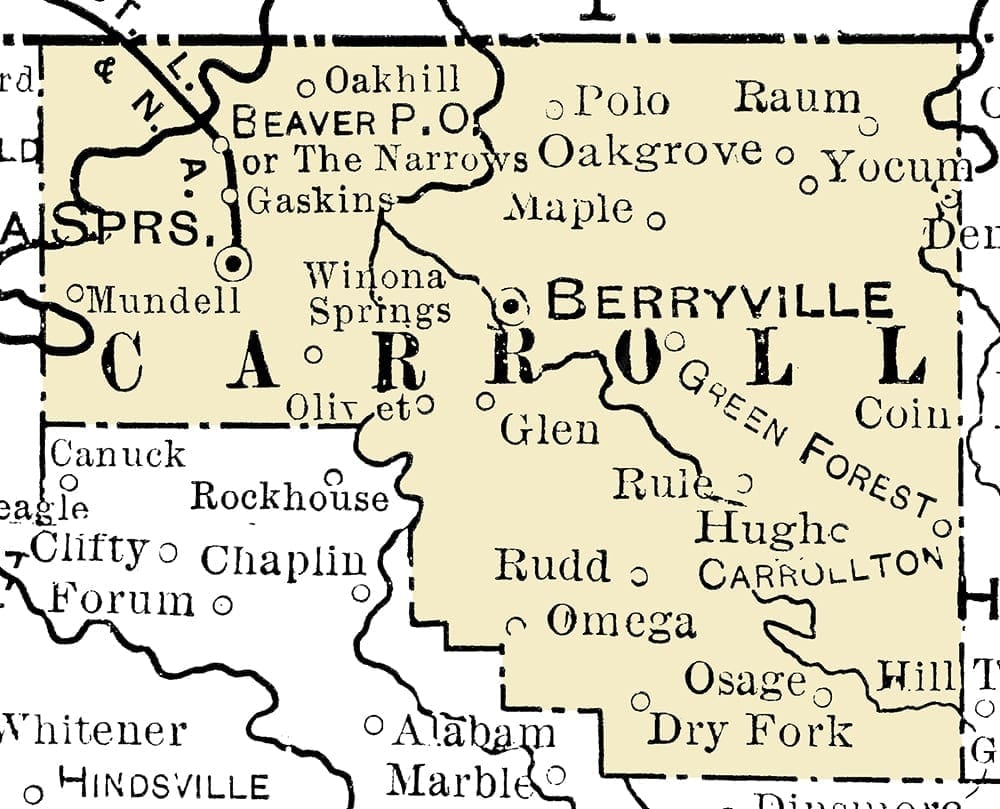

Carroll County was formed in 1833. It was named for Charles Carroll of Maryland, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence. The county’s boundaries changed frequently in its early years. Created from Izard County, land was added or taken from Madison, Searcy, Newton, and Boone counties.

Early settlers built log homes, farmed the land, established communities, and organized churches, schools, businesses, and governmental agencies. Some settlers brought enslaved people to work for them, but these African Americans were only a fraction of the county’s population. Still, families and neighbors split their loyalties during the Civil War over the issues of slavery and states’ rights. While no major battles were fought in Carroll County, skirmishes and lawless bushwhackers caused much harm.

19th Century Settlement

For a time the area now called Carroll County was the hunting grounds for the Osage. But they were forced out as white settlement in the East began pushing other Native American groups west. In 1838 about 16,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes, moving through Arkansas to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) along the “Trail of Tears.” Some 1,200 Cherokees and enslaved people followed the Benge Route through Carroll County, from Osage and Carrollton in the east down to Huntsville (Madison County) and beyond.

Carroll County was formed in 1833. It was named for Charles Carroll of Maryland, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence. The county’s boundaries changed frequently in its early years. Created from Izard County, land was added or taken from Madison, Searcy, Newton, and Boone counties.

Early settlers built log homes, farmed the land, established communities, and organized churches, schools, businesses, and governmental agencies. Some settlers brought enslaved people to work for them, but these African Americans were only a fraction of the county’s population. Still, families and neighbors split their loyalties during the Civil War over the issues of slavery and states’ rights. While no major battles were fought in Carroll County, skirmishes and lawless bushwhackers caused much harm.

20th-Century Growth

Poultry processing plant, Berryville or Green Forest, 1960s-1970s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-86-211-46)

The railroad was a driving force in determining whether a town prospered or faded. When Alpena Pass was created along the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad in 1900, Carrollton merchants moved their businesses and buildings to the new town. The railroad allowed markets to grow. Farmers grew fruit and vegetables to take advantage of the many canneries springing up, while sawmill operators turned trees into such materials as lumber, railroad ties, and barrel staves. Eureka Springs faded as medical practices evolved and the railroad moved its jobs to Boone County.

Carroll County wasn’t wealthy in the early part of the 20th century, so its largely rural, self-sustaining residents were better prepared to weather the economic woes of the Great Depression. Federally sponsored New Deal projects helped employ citizens in the 1930s. Workers built a gymnasium for Berryville, a water tower for Green Forest, an elementary school for Osage, and the Lake Leatherwood Park complex for Eureka. The Rural Electrification Act of 1936 provided federal loans to install electrical distribution systems. In 1938 Carroll Electric Cooperative of Berryville began constructing power lines, bringing power to many. Today their lines stretch across Northwest Arkansas and Southeast Missouri.

During World War II residents left to serve in the armed forces or work in war-related industries. But several factors led to later growth in population and economic opportunities. Large-scale chicken and turkey farming began in the 1950s when Berryville businessmen formed Carroll County Food Products. After Tyson Foods purchased the plant in the early 1970s, the county saw an influx of Latino residents. The construction of Table Rock and Beaver Lakes to the north and west brought tourism and encouraged the growth of family-style attractions such as Dinosaur World and the Great Passion Play. Eureka rebounded as a tourist destination, especially after incoming artists and others reopened long-shuttered downtown shops in the 1970s.

“The tomato industry of Carroll county ranks along with that of dairying, cattle and poultry. …The plants come into bearing about the middle of July and bear up to the middle of October, giving employment on the farm and at the canning plants at a time when most of the farm work is out of the way.”

Berryville Arkansas promotional booklet, mid-late 1930s

21st-Century Future

Today there are nearly 28,000 residents, with Berryville, Eureka Springs, and Green Forest as the county’s largest towns. Folks in Berryville and Eureka are often seen as different from one another, by outsiders and by themselves. Eurekans have a higher per-capita income than folks in Berryville, lean liberal in their politics, and look to tourism and the arts for their economy and identity. Industry is the major economic force in Berryville, politics are more conservative, and the population is twice the size of its western neighbor. With its poultry-processing plants, Tyson Foods is the largest employer in Berryville and Green Forest. Both towns have sizable, foreign-born populations.

The Carroll County Collaborative is a nonpolitical group made up of governmental, private, public, and nonprofit entities and organizations. It works to improve life for county residents and provide greater opportunities. Some of its priorities include affordable housing, new business development, conversion charter schools, and workforce development through such means as academies, incubator and apprentice programs, and a culinary institute. The Collaborative believes the county is “poised to be the next NATURAL growth area in Northwest Arkansas.”

“The Kings River divides Carroll County, and that’s where Woodstock and livestock meet.”

State Representative Bryan King of Green Forest

Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 19, 2010

“The nice thing about being in Berryville is you can drive ten miles west [to Eureka Springs] and it’s like you’re in a different country. You have restaurants. You have entertainment. Then you can go back home to the real world.”

Berryville Mayor Tim McKinney

Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 19, 2010

Carroll County Close-Ups

Early Settlers

The first settlers were Native Americans, having moved west from their ancestral homes ahead of white migration. White chroniclers made mention of Delaware Indians on Long Creek, small bands of Shawnee near what is now Alpena, and a Cherokee settlement north of what is now Berryville. Some of these early residents married the white settlers who came from Tennessee and Kentucky primarily. Around 1820 William Sneed of Kentucky traveled to the Ozarks with his wife, children, and enslaved workers. But, before moving, he surveyed the available land, made his choice, and planted several acres of corn. Making “improvements” by clearing fields, planting crops, and building homes was an important first step when claiming land from the government. In 1830 Sneed and his son, Charles, claimed several thousand acres of the best farmland in Osage Township. Their slaves helped build the Dubuque Road—the first road in the county—from Lead Hill through Carrollton and beyond. Charles served as Carrollton’s first postmaster and as county sheriff. Early court cases were held in the Sneed home.

Some of the first businesses were grist mills, tanneries (to prepare leather), blacksmith shops, and trading posts for things the settlers couldn’t make or grow themselves. Tilford Denton and his brother moved to the county seat of Carrollton in 1837 and set up shop as merchants. One year later their merchandise was valued at $2,800. Some settlers stayed for a short while before moving on. In 1857 Captain Alexander Fancher of Osage led family members and others on a wagon train headed for new opportunities in California. When they stopped at Mountain Meadows, a valley in the Utah Territory, most were attacked and killed by Mormons and Native Americans. The reason for the massacre has been hotly debated since then.

Civil War

Civil War veterans’ reunion, Basin Spring Park, Eureka Springs, circa 1900. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-45)

Arkansas seceded from the Union in 1861. Soon, Confederate and Union troops formed, pitting neighbors and family members against one another. While no major battles were fought in the county, there were several skirmishes and much guerilla activity. A group of lawless bushwhackers strung “old and feeble” Lige Massingale over a tree limb and burned his feet to get him to tell of hidden valuables. Having no luck, they set fire to his house. One legend tells how a small band of Confederates were able to capture a larger group of Union soldiers at Hog Scald Hollow by tricking them into getting drunk on corn whiskey. The soldiers seized a wagon as it was driven by their camp and discovered the liquor that had been hidden (on purpose) under the hay.

The upland counties of northern Arkansas had fewer enslaved workers than the rest of the state, owing to the hilly terrain which made plantation-style agriculture impractical. In 1860 the county’s population was just over 9,000 residents, 330 of whom where slaves. While their labor contributed to the economy, it was not a major factor. Perhaps this helps explain, in part, the formation of several Peace Societies along the state’s northern border, including one in Carroll County. While members of the societies opposed the Confederacy, they generally didn’t work against it, often preferring peaceful dissent and home protection to active conflict.

“Alsie [Holland] gathered up a heap of stones…they heard the tramp of horses’ hoofs and the renegades arrived. They came blustering in and demanded food, money and anything of value… One ruffian noticed the pile of stones on the hearth and asked what they were there for; aunt Alsie replied ‘those are secesh [secessionist] biscuits; have one’ she then proceeded to pounce the rocks on the fellow…”

Nora L. Davis Standlee

Carroll County Historical Quarterly, June 1957

Tornadoes

Tornado-damaged home, Green Forest, March 1927. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-14-21)

Carroll County has endured several destructive and deadly tornadoes. In 1927 nineteen people were killed and one hundred injured in Green Forest as a storm damaged the business district and destroyed about fifty homes, wrecking many more. A train car of doctors and nurses came from Harrison to help the injured, taking many to the Eureka Springs Hospital. Ten years later, Green Forest was struck again along with nearby Alpena Pass, with one person dead and twenty injured.

The worst tornado in county history struck Berryville at 10:30 p.m. on October 29, 1942. Right before the storm hit the power went out. As the Wyrick family hid under a mattress, they felt no motion as the storm picked up their house and moved it several feet. At the railroad station the tornado knocked over fifty-ton railroad cars and wrenched a baby out of its mother’s arms, badly hurting the mother and killing the child. Several businesses were demolished, including wholesale grocery houses and canneries, part of the economic lifeblood of the community. Rescuers searched for victims “by torch, flashlight, lanterns, candles, or even matches.” In all, twenty-nine people were killed, with sixty-eight seriously injured. The devastation made national news.

“They’re laying the dead out on the lawns as fast as they can get there out of the wreckage and we’re making regular trips picking up the bodies. Most of them are so badly mutilated that we can’t hope to identify them until relatives start coming in.”

Rex Nelson, undertaker

Northwest Arkansas Times, October 30, 1942

County Seats

Carroll County Courthouse—Eastern Judicial District, Berryville, about 1905. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-148)

The first seat of government was in Carrollton which, by the mid-1800s, was a large, centrally located, thriving settlement. But when Carroll County land was taken to form Boone County in 1869, Carrollton found itself on the border. A “courthouse war” erupted, pitting Carrollton against Berryville to the northwest. Petitions, elections, lawsuits, and countersuits followed as the two towns struggled for the courthouse and the prestige and revenue it would bring. In 1875, by a narrow margin of twenty-eight votes, the county seat was moved to Berryville.

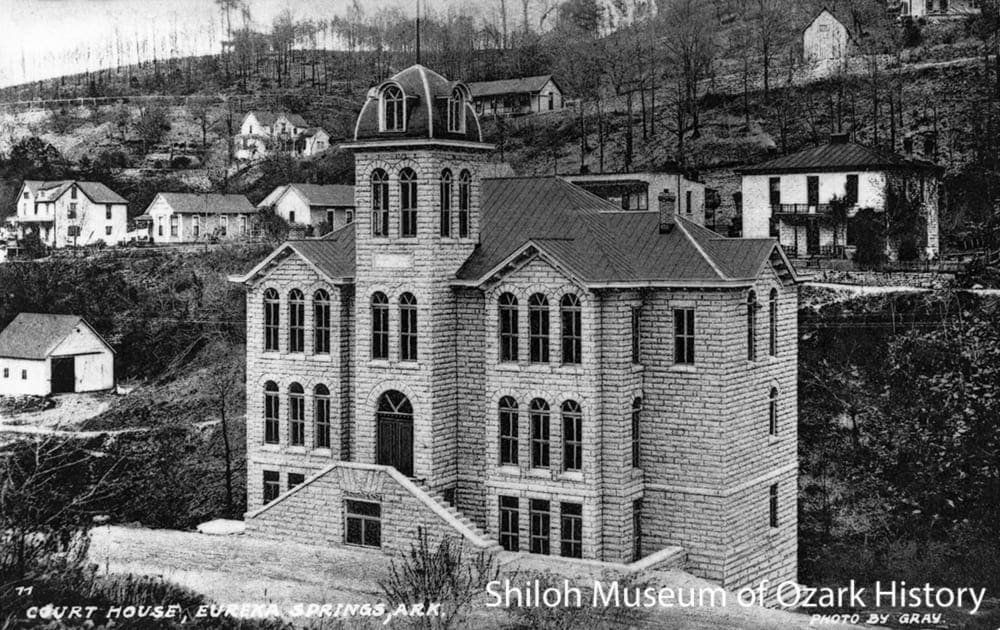

Carroll County Courthouse—Western Judicial District, Eureka Springs, about 1910. Siloam Springs Museum Collection (S-83-300-72)

Across the Kings River was the new boomtown of Eureka Springs. Its residents wanted the convenience of their own courthouse, in part to avoid impassable roads due to the frequent flooding of the Kings River. In 1883 they successfully petitioned the Arkansas Legislature to form two judicial districts with the Kings River as the dividing line. By the late 1880s Green Forest challenged Berryville for its courthouse, saying the building was unsuitable and in disrepair. The votes were tallied and Berryville kept its courthouse (later moving to a modern facility in 1976). The most recent dispute occurred in 2010 when a circuit court judge, a native of Berryville, ruled to consolidate the two judicial districts into one at Berryville. He was unsuccessful. Today the former Berryville courthouse is home to the Carroll County Heritage Center while the old Eureka Springs courthouse is home to the county clerk’s office and city offices.

“I have seen thousands of Texas Longhorn steers pass through town [in front of the courthouse] in droves nearly every week in the year, as well as horses, sheep, goats and one time there was a herd of 500 turkeys…some of the merchants didn’t like the flies the stock drew, especially in warm weather.”

D. Elmer Jones, 1957

Carroll County Historical Quarterly, December 1966

Railroads

The first St. Louis & North Arkansas train pulling into Berryville, April 15, 1901. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-81)

In order to continue the success of Eureka Springs, a railroad was needed to bring health- and pleasure-seekers. Former Arkansas governor Powell Clayton spearheaded a project to connect with the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad eighteen miles north. In 1883 the Eureka Springs Railway steamed into town. Together the two railroads built and operated the magnificent Crescent Hotel. But the Eureka railroad began to lose money as the fad of “taking the waters” began to wane. It was purchased by the St. Louis & North Arkansas Railroad in 1900, which began expanding the line west. Berryville and Green Forest each offered a bonus to bring the railroad to their towns but the terrain was too difficult and therefore too costly. But Berryville persevered. Residents gave the railroad money, right-of-way, and materials to build a spur line to town. In 1901 residents greeted the train with flower-decorated carriages.

A few years later the new railroad was failing and the line switched hands again. In 1906 it became the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA), followed by the Missouri & Arkansas Railway in 1935 and the Arkansas and Ozarks Railway in 1949. While the railroads had some successful years, there were many problems. The line was abandoned in 1961. In recent years the county has been home to two short, standard-gauge tourist railroads. The Eureka Springs Railroad operated out of Beaver for a time in the 1970s and early 1980s, but didn’t prove successful. The Eureka Springs & North Arkansas Railway, begun in 1981, operates out of the historic 1913 M&NA depot.

“Eureka Springs and Green Forest turned out in masses to help Berryville celebrate the arrival of the first train within her borders and rejoices with her in her good fortune. There is a popular superstition that these towns are jealous of each other, but no suspicion of such a situation showed up on this wonderful day . . .”

Berryville Progress, June 1901

Education

Clarke’s Academy, Berryville, 1913. Pennington, photographer. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-18-18)

Early Carroll County schools were subscription-based, meaning that students paid for their education. Professor Isaac A. Clarke founded an academy in Berryville in 1867, growing from twenty-five students to one hundred by the end of the first term. In 1879 first level tuition was $10, while Latin and Greek was $12.50 extra. The academy served students for nearly forty years. The Carrollton Academy began in 1877 as a “normal school,” where young men and women trained to be teachers. Years later the school’s 200 students “lined up in front of [their] old building with slates, dinner pails and books to march across town and occupy [their] new building.”

Osage Elementary School students with teacher Naomi McMorris (middle row, far left), 1939-1940. The building was constructed by Works Progress Administration workers as part of New Deal relief efforts. Ruth Sisco Curnutt Collection (S-85-284-76)

Eureka Springs had several small schools in its early years, including one for the children of African-American servants of wealthy vacationers. By the 1900s there were many small public school districts throughout the county, some with fanciful names like Blue Eye, Welcome Home, Grassy Nob, Parrott, Bobo, Gobbler, Snow, Possum Trot, and Hottentott. When Mabel Cripps Wilson began her teaching career in 1923 in the White Oak community, students walked one or two miles to school, brought their lunches in Karo syrup buckets, and went without shoes until the weather turned cold. These rural, one-room schools faded as communities dwindled and schools were consolidated in 1965. Today’s schools are in Eureka, Berryville, and Green Forest.

“Parents and guardians, confiding their children and wards in our care, may rest assured no effort will be spared to secure the development of mental powers and the lasting influences of moral principles upon the mind.”

Isaac A. Clarke

Clarke’s Academy for Males and Females, August 15, 1879

Sports and Recreation

Basketball team, Green Forest, 1916. From left: Hattie Belle, Ruth, Ethel, Eloda, Rhea, Hazel, and Augusta. James and Sue Eldridge Collection (S-96-2-940)

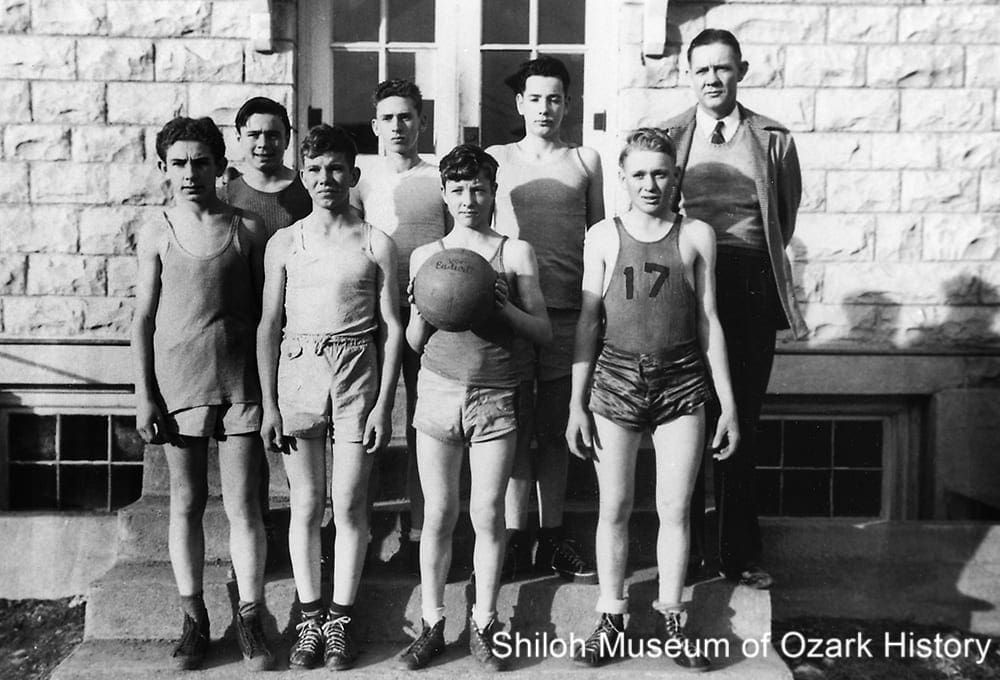

Baseball teams began to form in Carroll County in the 1880s in such communities as Beaver, Denver, Farewell, Eureka Springs, Oak Grove, and Rule. During the summer special excursion trains brought crowds to the baseball field near Beaver. Public schools in the county’s larger communities fielded sports teams, including basketball for girls. In 1924 Eureka Mayor Claude A. Fuller received $500 towards the construction of Harmon Park. Wealthy New Yorker William E. Harmon provided money to construct playgrounds, because he wanted to provide “inspirational and tangible help for young people.” The Harmon Foundation recently donated funds towards the construction of a skate park, an ADA-accessible playground, and a future spray park.

The Saunders Memorial Muzzleloading Shoot began in 1954 in honor of Colonel C. Burton “Buck” Saunders, a longtime Berryville resident who was a skillful marksman and collector of unique firearms. Activities at Luther Owen’s Muzzle Loading Park include firearm matches, camping, and the sale of black-powder merchandise. In 1930 Albert Ingalls, Eureka Springs mayor and president of Crescent College, wanted a basketball team for the girls’ school. Hearing about a winning team in Sparkman, Arkansas (southeast of Hot Springs), he sent his wife Leila to recruit the girls. The Crescent Comets practiced in the basement of the city auditorium, running the distance from the Crescent Hotel and back. The team won two national championships.

“We loved it… And even though the school was for rich girls, our team [the Crescent Comets] was accepted with kindness from the regular students. …We got to dance in the lobby with all the other girls and we looked just as nice. Mrs. Ingalls saw to it. Before the college’s first formal, she bought each member of our team a formal gown from a fancy dress shop in Springfield [Missouri] so we could go and feel like we fit in.”

Mabel Blakely Williams

1886 Crescent Hotel & Spa blog, posted September 29, 2012

Health

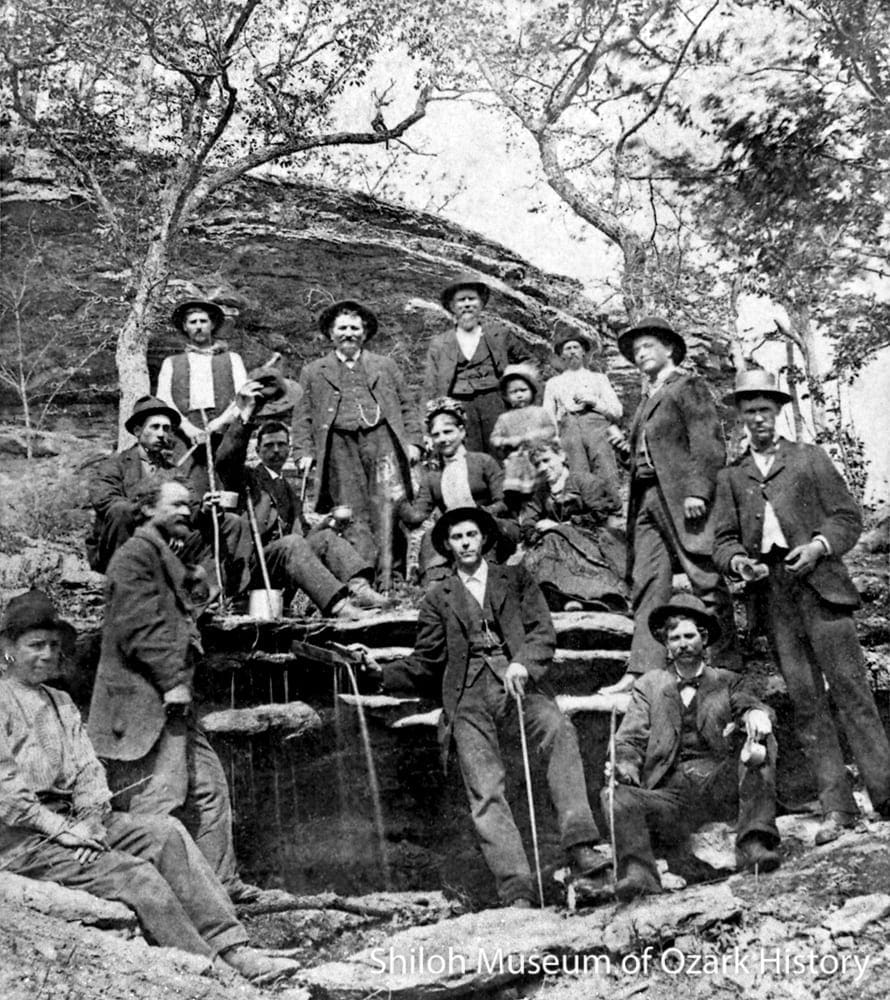

Health seekers by spring, Eureka Springs, about 1881. F. F. Fyler, photographer. Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Collection (S-83-325-39)

Carroll County’s first doctor may have been Arthur A. Baker, a blacksmith who taught himself medicine by reading books. Working first out of Carrollton and later Berryville, he traveled many miles by horseback to treat neighbors in need. In 1879 Dr. Alvah Jackson treated a patient suffering from severe skin disease using water from a healing spring. His miracle cure at Basin Spring led to a massive influx of health-seekers and entrepreneurs into what would become Eureka Springs. More springs were discovered, their mineral content tested, and their curative powers touted. Eureka went from a campsite to a town of nearly 4,000 in the space of one year. Entrepreneurs built fancy hotels, bathhouses, and sanitariums to treat the infirm. The springs were said to cure a host of illnesses including rheumatism, catarrh (inflammation of mucus membranes), tuberculosis, hay fever, diabetes, dyspepsia (indigestion), asthma, jaundice, malaria, paralysis, neuralgia (intense nerve pain), gout, cancer, dropsy (excess fluid in tissues or body cavities), and “female troubles.”

Frances Kerens felt that Eureka’s Catholic community needed a religious order to “help solve the problems of those in need of spiritual replenishing.” In 1900 land was purchased for the Hotel Dieu Hospital. Run by the Sisters of Mercy Motherhouse in St. Louis, the facility included a convent, school, chapel, surgical wing, and twenty-five-bed hospital. Financial problems led to its closure in 1913. An infamous chapter in Eureka’s medical history began in 1937 when Norman Baker purchased the shuttered Crescent Hotel to open a cancer hospital. A long-time quack who made millions by swindling the ill with bogus cancer treatments, he was finally sent to jail in 1940.

Other early hospitals include the Don Sawyer Memorial Hospital (now the Eureka Springs Hospital) and the Gentry Hospital in Berryville. In the 1930s and early 1940s, Vera Gentry was a midwife who ran a hospital in her home, welcoming about 300 babies into the world. Doctors used her hospital to perform tonsillectomies and appendectomies. Gentry’s hospital closed when Dr. Parker and Dr. Carter’s eleven-bed hospital opened in town, which in turn closed in 1969, shortly before the opening of Carroll General Hospital (now Mercy Hospital Berryville). Money for the facility came from a county tax and a grant. In 2016 the hospital caused some concern when it ended several services, including emergency ambulance, home health, and hospice.

Eureka Springs Memorial Hospital administrator Leonard Pratt with staff, January 10, 1974. Springdale News Collection (SN 1-10-1974)

The rise of Eureka as a spa town coincided with the end of the nation’s interest in “taking the waters.” Many factors contributed to bring this about including major advancements in science, improvements in the standards of medical care, and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. By the 1910s the grand Crescent Hotel had closed its doors and fewer health-seekers came to town. As Eureka transformed into a tourist town, interest in saving the springs grew. Preservationists restored several springs and their protective structures. Today they are open to the public, although they bear signs warning folks against drinking contaminated water.

“People who have been bedridden sufferers for years come here, drink the waters, and get well, often in a very incredibly short time… Ladies who have languished for years in their terrible mind-wrecking and body-destroying ills arrive here and in a few months at the furthest, are seen with the bloom of health upon their cheeks and rejoicing in restored womanhood.”

Eureka Springs Daily Democrat, December 17, 1891

Natural Resources

Young ‘possum hunters, Oak Grove, about 1917. From left: Ertie Allen, Gilbert Wiley, and Eli Shahan. At the time, a properly tanned hide could bring up to twenty-five cents. Larry Parmlee Collection (S-85-5-17)

When settlers first came to Carroll County they found abundant natural resources—timber and stone to build with, animal pelts to trade for cash and goods, and plentiful game and fish to eat. One story tells of two women from the Beaver community who, having lost food and livestock to Civil War bushwhackers, were desperate to feed their families. They killed a number of deer by herding them into the woods and flapping their aprons to drive the deer off a high bluff to their death. In recent years the deer population in Eureka Springs had grown so large that, after much opposition, an urban deer hunt was organized in 2013 for bowhunters.

Some of the earliest sawmills were located on the Dry Fork Creek in 1840s. In the days when land could be claimed from the federal government by “improving” and using it, Franzisca Massman of the fast-growing town of Eureka stayed one step ahead of the law. She would find a choice spot (even if it had already been claimed by someone else), erect a cabin, move in a few furnishings, cook a meal, and plow a patch of ground. Once the usable timber had been cut she moved to a new claim. By the 1900s an expanding railroad allowed sawmills to ship lumber, barrel staves, and railroad ties throughout the region. Sawmill operations continued well into the 20th century, with operators producing oak flooring, shipping pallets, and pine posts treated with creosote.

A. L. Hanby’s steam-powered sawmill, Winona, 1890s-1900s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-186)

Rumors of vast oil fields in Northwest Arkansas led to the Sure Pop oil well in Eureka in 1921. Promoted by a Texas driller who promised great wealth, business leaders raised $10,000 to buy land. A derrick was built, oil leases were sold, a barbecue was held for 2,500, and newspapers told of the progress at the well site. But the well was never drilled and the Texas promoter left town after the derrick burned down mysteriously. Sure Pop shareholders with left with worthless leases.

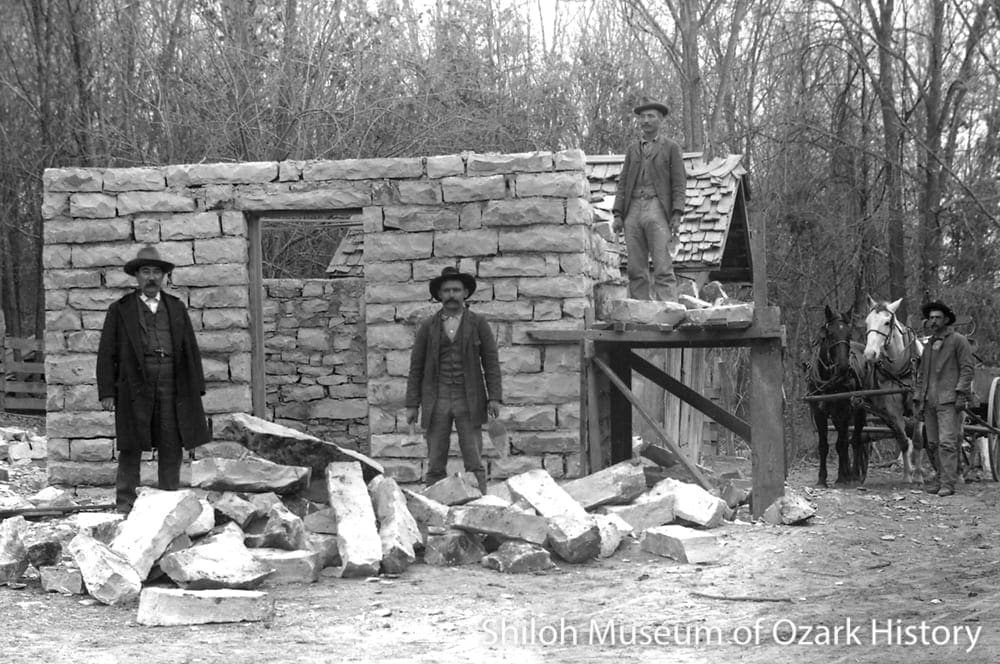

The Crescent Hotel and other buildings in Eureka were built using high-quality, local limestone. The Eureka Stone Company, founded in 1904, used the railroad to ship its product throughout the region. When building projects grew scarce, the company fell dormant. In the late 1970s stonemason Don Underwood bought modern equipment and reopened the quarry. Today the company supplies stone for commercial and residential projects throughout Northwest Arkansas and the region. It also takes on restoration projects of some of Eureka’s old buildings and walkways.

“…Ab [Hanby] inherited a disposition to work…he acquired the habit of greasing his muscles with brains, so to speak, and as a result he has sawed more lumber for homes in the Eastern District of Carroll County than any other three men who have been engaged in the lumber business here. He has in time owned no less than forty different mills, having a dozen or more in operation at one time.”

Green Forest Tribune, December 19, 1913

Agriculture

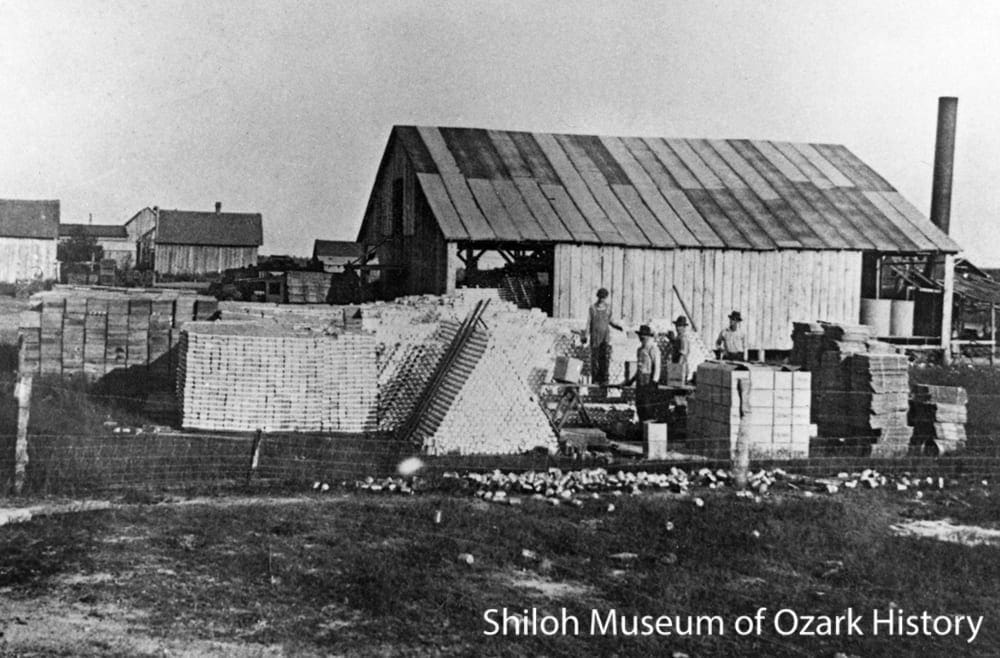

Cans stacked outside the Hays Canning Company, Oak Grove, 1910s. Larry Parmlee Collection (S-85-5-29)

By 1913 there were large-scale canneries at Berryville, Urbanette, and Green Forest, with the latter shipping 8,000 cases of apples, 6,000 cases of tomatoes, and 6,000 cases of peaches that year. Wheat was an important crop and kept the flour mills in Green Forest, Urbanette, Yocum, and Berryville grinding away. Flour was shipped regionally and even overseas during World War I. By the 1920s the boom-and-bust cycle of crops forced farmers to diversify. Tomatoes were grown in the 1930s, supplying around thirty canneries before the industry declined from disease and the “labor-intensive nature of the tomato business.”

Dairy herds became big business for a time. In the early 1930s the Berryville Cheese Factory operated out of the basement of a hardware store. Later a large stone building was purchased where cans of milk were brought, pasteurized, and made into cheese. Kraft Foods purchased the business in 1946 and modernized the plant, offering high-paying jobs to local workers. The plant closed in 1985, in part due to improvements made to Kraft’s Benton County facility.

While Eureka Springs’ economy shifted from healing springs to tourism over the years, agriculture-related businesses continue to be a mainstay in the rest of the county. In the 1960s Green Forest was home to two of the state’s thirty beekeepers who rented their hives to commercial fruit growers for crop pollination. Three Berryville businessmen started Carroll County Food Products in 1951, processing chickens and turkeys. By 1971 the plant was owned by Tyson Foods. Today Tyson employs nearly 3,000 county residents in several poultry-related businesses, including processing plants in Berryville and Green Forest, making for an annual payroll of $138 million. Tyson, Walmart, Carroll Electric Cooperative Corporation, and Mercy Hospital are the county’s largest employers.

“…the short nutritious grasses have proved to not only contain sufficient nourishment to sustain the life of large herds of cattle, but to actually fatten them during the winter months, and it is an actual fact that thousands of cattle and hogs are bred, born, and raised on the large areas of free range, brought to town, and shipped to market without ever seeing a grain of corn in their lives.”

Oak Leaves, 1914

Diversity

African Methodist Episcopal Church members at Harding Spring, Eureka Springs, late 1910s. Harding was the only spring open to African Americans. Eureka Springs Historical Museum Collection (S-99-66-359)

Carroll County’s African American population has always been small in comparison to its white population. In 1860 there were a little over 9,000 residents, 330 of whom were enslaved workers. After the Civil War only thirty-seven former slaves stayed in the area. But the new boomtown of Eureka Springs offered economic opportunities. Blacks owned boarding houses and worked in bathhouses, hotels, laundries, and barbershops. They improved their community by building homes, establishing a school, and organizing an African Methodist-Episcopal Church. But they were segregated from the white community—limited by where they could live, work, shop, and spend leisure time. As the health resort faded in the early 1900s, many moved away.

Berryville was considered a “sundown town.” It’s said that signs were still posted in the 1950s warning blacks not to stay past nightfall. Today the county is largely white, with a few folks self-identifying as African American, Native American, Asian, and Pacific Islander. There is a sizable Latino population, many of whom work in the poultry industry.

“Uncle Dick Fancher . . . was buried in the colored people’s cemetery [in Eureka Springs]… He was sold as a slave at auction here in Berryville when he was but ten years old and was bought…for $400 [in 1848].”

Benton County Democrat, May 11, 1911

Back to the Land

“First Dance” at the Ozark Mountain Folkfair, Eureka Springs, May 1973. A singer with the Lewis Family (center) dances with a Folkfair staff member. Albert Skiles, photographer. Courtesy Albert Skiles.

In the 1970s Northwest Arkansas saw an influx of young adults seeking a simpler, more meaningful life. Edd Jeffords of Eureka Springs published the Ozark Access Catalog, with tips about buying land and planning a garden. He told newcomers to work hard and “learn about the lives and customs of the people they were living beside.” Over twenty folks lived in the Lothlorien commune near Berryville. They helped their neighbors with farm chores and paid their electric bills by working as waitresses, artisans, and the like. In 1973 Jeffords helped put together the Ozark Mountain Folkfair, a three-day event featuring such musicians as John Lee Hooker and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Thousands of youngsters braved heavy rain, mud, and ticks to attend.

Some folks accepted and helped the newcomers while others saw them as immoral hippies and drug addicts who took advantage of the welfare system. In 1972 the Eureka Springs Times-Echo warned of a “well-oiled plot” by the “longhairs” to take over city government. Back-to-the-landers moved into Eureka’s vacant storefronts, selling such things as health food, handmade leather items, and even a “Christ of the Ozarks marijuana cigarette clip.” While some moved away in the 1980s, others stayed and became teachers, artists, and city-council members. Richard Schoeninger, who came to Eureka to edit an underground newspaper, served as mayor in the late 1980s. He jokingly reported two problems with his job—following rules and wearing underwear.

“In not voting, you gave up your right to vote for someone else—who, for all you know, was a Communist, an extremist of one sort or another, or a hippie who has added nothing to the community…”

Dick Fisher, editor, Eureka Springs Times-Echo

Arkansas Gazette, June 25, 1972

“The polite woman who waits on you in any café may likely as not be ‘an extremist of one sort or another’ during her free time. People here are employed making looms, rewiring houses…dishwashing…teaching horseback riding… We certainly haven’t hurt the town economically.”

Maren Statts

Arkansas Gazette, June 25, 1972

Entertainment and Tourism

Joanie O’Bryant performing at the City Auditorium, Ozark Folk Festival, Eureka Springs, October 1962. Ernie Deane, photographer. Frances Deane Alexander Collection (S-2012-137-628)

James Braswell of Green Forest has been called the “Stephen Foster of the Ozarks” after the 19th-century’s great American songwriter. In 1890 at age seventeen he became the director of the Green Forest Cornet Band. He wrote his first song, “Meet Me at the Basin While in Eureka Springs” when he was hired one summer to play cornet in the resort town. Back then, Eureka residents enjoyed special July 4th excursions on the Eureka Springs Railway, riding on flatcars across the White River bridge near Beaver to picnic, play baseball, and watch fireworks.

Recreation lovers use Carroll County as their jumping-off point to take advantage of camping, hiking, fishing, hunting, and boating opportunities at Beaver Lake to the west and Missouri’s Table Rock Lake to the north. But the powerhouse of county tourism is Eureka Springs. When Eureka faded as a spa town, population and business declined. In the late 1940s Dwight Nichols and a partner bought the Crescent Hotel on the cheap, only to realize that vacationers were few and far between. Nichols offered a six-day package for $40 through a Chicago travel agency. About 150,000 tourists visited in 1958.

The first Ozark Folk Festival was held in Eureka in 1948 to preserve and continue the area’s native arts of music, dancing, and craftsmanship. Many musical legends have performed at the festival including Doc Watson, Almeda Riddle, Fred High, and Jimmy Driftwood. The festival features many beloved traditions such as the Barefoot Ball, a Queen’s Contest, a parade, and a square-dancing presentation by the HedgeHoppers, third-grade students from Eureka Springs Elementary School. Newer festivals celebrate bluegrass, jazz, blues, art, film, and Mardi Gras.

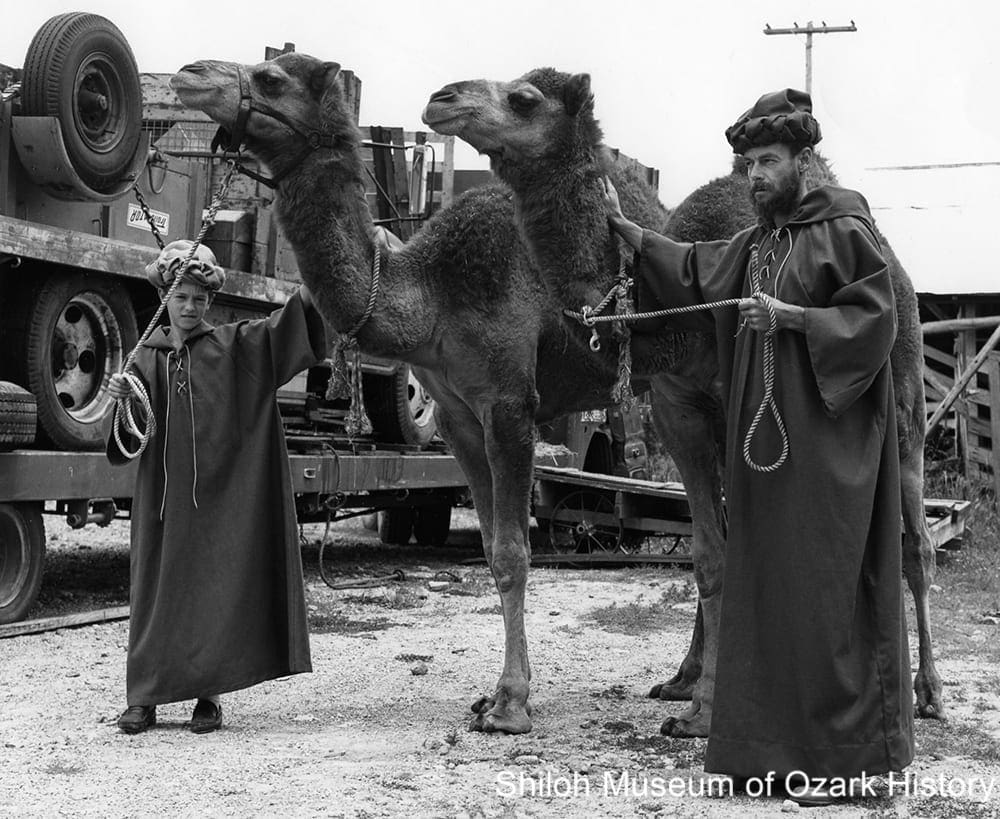

Performers prepare for the Great Passion Play, Eureka Springs, 1968. Dwight Nichols, photographer. Frances Deane Alexander Collection (S-2012-137-173)

Tourism increased during the 1960s with the coming of Beaver Lake and other tourist attractions like Dinosaur World, Quigley’s Castle, and Gerald L. K. Smith’s Christ of the Ozarks statue and the Great Passion Play. Residents had mixed feelings about Smith, a minister who supported anti-Semitic and fascist causes throughout his life. But the play, based on the last days of Jesus Christ, was popular. Economic downturns and changing visitor interest nearly closed the complex in 2012, but operators trimmed costs to stay open.

In the 1970s a number of artists moved to town, opening downtown stores to sell their work. Back then, Eureka advertised itself as the “Little Switzerland of the Ozarks.” Today it bills itself as the “Wedding Capital of the South.” In fact, Eureka made headlines in 2014 when it issued the first same-sex marriage license in Arkansas. Recently there has been an effort to promote the town as gay- and motorcycle-friendly, with some opposition. With 1.5 million visitors annually, Eureka is appreciated for the quality of its visual art and musical offerings. It has kept up with the times, offering such activities as ghost hunts, zip-line adventures, and winery tours.

“Now some folks just don’t care for oldtime fiddle music. . . . I reckon the more sophisticated run of people wouldn’t find it funny when Toby [Baker’s] gourd ‘gittar’ bursts into flame and smoke smack in the middle of a ditty [at the Folk Festival]. But these men and others are preserving some of the things that made the mountain country what it was before paved highways, television and electric washing machines brought upheaval to the hills.”

Ernie Deane

Arkansas Gazette, October 21, 1958

“We want the town full, not congested. Our economy depends on tourism. But we’re no shopping mall. We’re a community. Eighty-five per cent of us, non-natives, came here because we fell in love with it. I didn’t want the town to go totally commercial. We need stewardship, not to devalue our history or ruin the legacy.”

Eureka Springs Mayor Richard Schoeninger

Arkansas Gazette, January 31, 1989

Religion

Baptism at the White River, possibly the Mundell Community, about 1915. Eureka Springs Historical Museum Collection (S-99-66-379)

Most early Carroll County settlers were Baptist or Methodist. A Union Baptist church was organized at Joel Plumlee’s Green Forest home in 1838. Services were held once a month, from Saturday morning to Sunday night. There was preaching, Holy Communion, foot washing (a ritual of humility), and river baptisms. Eureka Springs’ fast-growing and diverse population brought new denominations.

Founded in 1882, St. Elizabeth Catholic Church moved into an impressive limestone building in 1909, complete with Italian mosaic floors and marble altars. Christian Science was introduced in the late 1880s by Lou Aldrich. Finding no relief from Eureka’s waters, she used prayer to treat her illness. She went on to become a healer herself, only to face legal action for “practicing healing without a medical license.” The case was dismissed after her attorney asked those healed by the new religion to stand (most stood) and then asked the same for those healed by doctors (nobody stood).

Today there is a wide variety of denominations in the county—Lutheran, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Unitarian—even Native American. In Green Forest there are two Spanish-language Southern Baptist churches for the local Latino population. The Rock Springs Baptist Church near Berryville may be the oldest still-active church in the county. It was founded in the early 1850s by Dr. Alvah Jackson, discoverer of Eureka’s famous Basin Spring. But as congregations dwindle, country churches face uncertain futures. Recently the Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas put the 1895 Possum Trot Church near Osage on its “Six to Save” list.

“We didn’t have a college education, but we did have a lot of kneeology. You get down on your knees and pray to God for knowledge and understanding.”

Anita Hudson, speaking about Possum Trot Church

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 8, 2009

Sounds of Carroll County

Carroll County storytellers Melvin Anglin (left) and Coy Logan, whose tales were included on the 1981 album, Not Far From Here.

Between 1970 and 1980 George West and William K. McNeil recorded folk narratives and folksongs of the Ozarks, resulting in the 1981 album, Not Far From Here. The project was sponsored by the Carroll County Historical Society and funded in part with grants from the Arkansas Arts Council, the Arkansas Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Endowment for the Arts, Folk Art Division.

Two of the project’s participants—Melvin Anglin (1906–1992) and Coy Logan (1906–1984)—were from Berryville. Both men learned their tall tales and stories of the Civil War from their grandparents. Thanks to George West, William K. McNeil, and the UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture, we offer the recorded stories of Anglin and Logan here for your listening pleasure.

Carroll County Communities Photo Gallery

Gristmill (left), Albert Buell’s home (center), and his store and post office (right), Cisco, 1920. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-14-8)

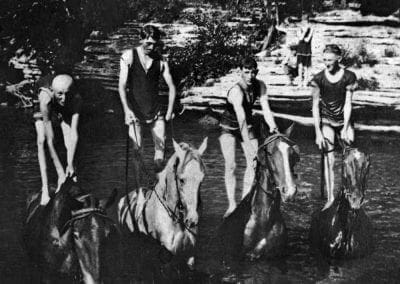

Blue Hole swimming hole, Osage, about 1912. From left: Fay Sisco, Booker Sisco, Arthur Shackleford, and Ray Sisco. Ruth Sisco Curnutt Collection (S-85-284-77)

Blue Eye School with teachers G. Waterman and R. Mays, Blue Eye, circa 1939. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-85-7-12)

W. H. Kirkpatrick at his hardware store, Alpena, 1910s–1920s. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-72)

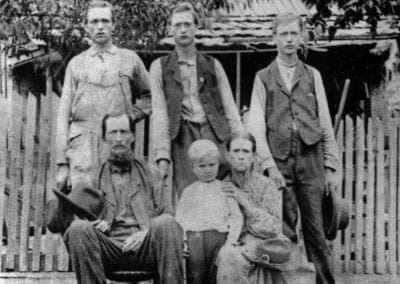

Taylor family, Dean, circa 1905. Back row, from left: Amos, Sam, and Charley. Front row, from left: Isaac, unidentified, and Carline. Dewey Taylor Collection (S-99-32-153)

Arkansas and Ozarks Railway freight train, Beaver, circa 1960. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-105)

Cabanal Post Office, circa 1950. Postmistress Ettie McKinney (left) and Mrs. Bill Hargis, (Berryville) Star Progress route carrier. Carroll County Heritage Center Collection (S-84-211-161)

Credits

“28 Known Dead in Berryville Storm.” Northwest Arkansas Times, October 30, 1942.

“35th Annual Ozark Folk Festival.” Unknown Eureka Springs newspaper, October 1982. Shiloh Museum research files.

“About the Festival.” Original Ozark Folk Festival, accessed October 2016.

“An Economic Analysis of Carroll County in Northwest Arkansas.” Center for Business and Economic Research, Sam M. Walton College of Business, University of Arkansas, August 30, 2002, accessed September 2016.

Andrews, James. “What about those new Ozark communes?” Memphis Commercial Appeal, circa 1974.

“Berryville Suffers Tornado.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Autumn 1993).

Bowden, Bill. “Abolish old law entirely, JP says.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 24, 2011.

Bowden, Bill. “Bowhunting inside town culls 12 deer.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 3, 2013.

Bowden, Bill. “Christ of Ozarks dark after 45 years.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 10, 2012.

Bowden Bill. “Eureka Springs Eternal: New Orleans Meets Switzerland In The Ozarks.” Spectrum, February 14, 1989.

Bowden, Bill. “Flags proposal raises a flap.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 24, 2013.

Bowden, Bill. “Passion Play cuts schedule, makes money.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 23, 2013.

Bowden, Bill. “River, politics, culture divide Carroll County.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 19, 2010.

Bowden, Bill. “Siblings trying to save old church.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 8, 2009.

Braswell, O. Klute. “Evolution of the Berryville Court Square Park.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XI, No. 4 (December 1966).

Breece, Marilyn. “1927, 1937 killer tornadoes struck Green Forest.” Boone County Historical & Railroad Society, Inc., August 4, 2006, accessed September 2016.

“Canning, Refrigerator Cars, and Fresh Produce.” Oak Leaves, Spring 1990.

“Carroll County, Arkansas.” Community and Conflict: The Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks, accessed September 2016.

“Carroll County, Arkansas: Its Land and Its People” (reprint of a 1914 publication of Oak Leaves), newspaper clipping, Shiloh Museum research files, August 1979.

“Carroll County Churches.” ShareFaith, accessed October 2016.

“Carroll County Collaborative.” Eureka Springs: Mayor’s Task Force on Economic Development, Greater Eureka Springs Chamber of Commerce, accessed October 2016.

Carroll County Historical and Genealogical Society. The History and Families of Carroll County, Arkansas. Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Co., 2003.

Carroll County Newspapers, Inc. A Pictorial History of Carroll County, Arkansas. Marceline, Missouri: Heritage House Publishing Company, circa 1990.

“Carroll County’s Leading Cannery at Green Forest.” Oak Leaves, Spring 1990.

“Carroll Electric Cooperative a Mighty Force in Development of Arkansas Ozarks,” Ozark Mountaineer, September 1956.

Chittenden, Mary Louise, editor. Carroll County, Arkansas: History and Reminiscences. Berryville, Arkansas: Carroll County Historical Society, 2005.

Chittenden, Mary Louise, editor. “History of Carroll County Arkansas.” Reprinted from Goodspeed’s Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northwestern Arkansas, 1889, and A Reminiscent History of the Ozark Region, 1892. Carroll County Historical Society: Berryville, Arkansas, 2005.

“Church Directory.” Carroll County News, accessed October 2016.

Clarke’s Academy for Males and Females broadsheet. Berryville, August 15, 1879. Shiloh Museum research files.

Dean, Jerry. “Eureka Springs: The portrait of a town hibernating for winter.” Arkansas Gazette, January 31, 1989.

Deane, Ernie. “An Important ‘Rental’ Item: The Honeybee!” Arkansas Gazette, May 26, 1968.

Deane, Ernie. “Toby, Absie, and Fred Help Spice Up Folk Festival.” Arkansas Gazette, October 21, 1958.

Dempsy, David Frank. “Holiday Island enjoys rich history and bright future.” Eureka Springs Times-Echo, March 1996.

Dodson, Lucile Russell. “The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad Comes to Berryville, Arkansas.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. V, No. 1 (March 1960).

Dougan, Michael B. “Norman Baker (1882-1958).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

Downey, Sheilah. “Civil War cave in heart of city to get a facelift.” Carroll County News, June 17, 1993.

“Dr. A. E. Quinn.” unattributed and undated article. Shiloh Museum research files.

Dragonwagon, Crescent. “An Ozarks Original: Eureka Springs, Arkansas, is a town at odds with the ordinary.” Discovery, Summer 1987.

Duggan, Tom. Unpublished manuscript about Northwest Arkansas railroad history, 2012–2014. Shiloh Museum research files.

Ellis, Mike. “The best little history of the best county in Arkansas.” Carroll County News Newcomer’s Guide, Summer 1998.

Ellis, Mike. “Union soldiers recognized a good thing.” Carroll County News, September 1, 1999.

“ES&NA Railway,” accessed October 2016.

Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library Association. Eureka Springs Pictorial History. Eureka Springs Times-Echo, 1975.

Eureka Stone Company, accessed September 2016.

Finck, James. “Mountain Meadows Massacre.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

Fletcher, Jim. “Civil War surrounded area with historical events.” Carroll County News, October 1992.

Fletcher, Jim. “The whole town moved: Carrollton still on the map, despite Alpena,” Green Forest Tribune, August 11, 1993.

Froelich, Jacqueline. “Eureka Springs in Black and White: The Lost History of an African-American Neighborhood.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LVI, No. 2 (Summer 1997).

“Gathering ‘Possums in the Ozarks.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. LIII, No. 4 (December 2008).

Gibson, Larry. “The way we were.” Unpublished manuscript, Fall 1993. Shiloh Museum research files.

Griffith, April. “Ozark Mountain Folk Fair.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed Ocotber 2016.

Griffith, April. “Ozark Mountain Folk Fair: History in Our Backyard.” The Back-Stay (Shiloh Museum blog ), June 7, 2013, accessed October 2016.

Handley, Lawrence R. “Settlement Across Northern Arkansas as Influenced by the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4 (Winter 1974).

Harper, Edward. “Eccentricity At an Old Spa In the Ozarks.” New York Times, May 28, 1989.

“Healing Waters.” Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, accessed September 2016.

“History.” St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church, accessed October 2016.

Housewright, Ed. “‘Little Switzerland’ focus of clash between old, new.” Arkansas Gazette, July 20, 1986.

Jackson, Jennifer. “Back to the Land, Again: Eureka-area commune members return for reunion.” Lovely County Citizen, May 29, 2014.

Jamison, Sylvia. “Carroll County schools: History, events retold.” Eureka Springs Times-Echo, August 9, 1985.

Jamison, Silvia. “Two courthouses cause history of controversy.” Eureka Springs Times-Echo, May 9, 1985.

Jeansonne, Glen, and Michael Gauger. “Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith (1898-1976).“Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed September 2016.

Jennings, John. “Hog Scald.” The History of Hogscald, accessed September 2016.

Jines, Billie. “White River residents accepted unusual Epsom salts deposit.” Northwest Arkansas Morning News, February 22, 1987.

Johnson, Boyd W. “Old Carrollton.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March 1957).

Johnson, Evelyn. “Early Sawmills of Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXIV, No. 1 (Spring 1979).

Jones, D. Elmer. “When Bales of Cotton Rolled Through Town.” Carroll County Historical Society, Vol. III, No. 3 (September 1958).

KInder, Kevin. “Tourist town puts old strengths, new interests out front.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 10, 2008.

Kuykendall, Kristal. “Same-sex marriage licensing starts, stops.” Lovely County Citizen, May 15, 2014.

Lair, Jim, and O. Klute Braswell. An Outlander’s History of Carroll County, Arkansas. Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth Publishing Co, Inc., 1983.

Lair, Jim. “The Hanbys: ‘Lumber Kings of Carroll County.'” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (Summer 1985).

Lancaster, Guy. “Arkansas Peace Society.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, accessed September 2016.

Loftis, Scott. “Mercy-BV administrator points to positives.” Carroll County News, July 12, 2016, accessed October 2016.

“Loftis, Scott. Tyson Expansion: Poultry giant proposes $136M plant in Green Forest.” Carroll County News, April 15, 2016, accessed September 2016.

Long, E. Alan. “Saunders Museum Turns 50.” Carroll County News, June 13, 2005, accessed October 2016.

Long, E. Alan. “Which came first, Presbyterians or Baptists?” Carroll County News, May 16, 2003.

Lucariello, Kathryn. “Beaver woman recalls start of Holiday Island.” Carroll County News, November 27, 2012.

Luster, Mike. “Looking for the Center of the Universe: Edd Jeffords and Ozark In-migration,” unpublished and undated manuscript, Shiloh Museum research files.

Maierhofer, Karen. “Many responsible for hospital.” Carroll County News(?) (Carroll General Hospital Edition), October 1984.

May, Bethany. “Eureka Springs (Carroll County).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, accessed October 2016.

McNeal, David. “Tennis Affair in Jeopardy After 70 Yrs.” Carroll County News, November 23, 1989.

Miller, C. J. “Carroll County.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed September 2016.

Mills, Nellie A. Other Days at Eureka Springs, 1950.

More, Kechia Bentley. “What’s in a Name? The History Behind Harmon Park.” River Valley Online, September 1, 2006, accessed Occtober 2016.

Mosenthin, H. Glenn. “Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History,. accessed October 2016.

Motherwell, David. “Berryville Kraft Cheese Plant.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. LLI, No. 4 (December 2007).

Motherwell, David. “The Trail of Tears went through Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. LIII, No. 1 (March 2008).

Newcomb, Kelby. “Ready, aim, fire Saunders Memorial Shoot sets sights on this weekend.” Carroll County News, September 21, 2016.

Ozark Mountain Folkfair program, 1973. Posted by Bob Treat on Flickr, accessed October 2016.

Parham, Jon. “ES looking to the future.” Carroll County News, March 1995.

Phillips, Jared M. “Hipbillies and Hillbillies: Back-to-the-Landers in the Arkansas Ozarks during the 1970s.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXXV, No. 2 (Summer 2016).

Polston, Mike. “Carrollton.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed September 2016.

Pyron, Shirley H. “A Slave Called Mariah.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. LV, No. 2 (June 2010).

Pyron, Shirley, H. “Vera Gentry’s Hospital.” Carroll County Historical Society, Vol. LVI, No. 1 (March 2011).

“Quick Facts, Carroll County, Arkansas.” United States Census Bureau, accessed September 2016.

Rea, Ralph R. Boone County and Its People. Van Buren, Arkansas: Press-Argus, 1955.

“Renowned Crescent Comet Mabel Williams.” 1886 Crescent Hotel & Spa blog, September 29, 2012, accessed October 2016.

“Resort Community Marks First Anniversary.” Holiday Island Sun, August 1971.

“Rock Springs Missionary Baptist Church.” 1956. Shiloh Museum research files.

Sabo, George, III. “Osage.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

Shiras, Ginger. “Longhairs, Sacred Projects Reviving Eureka Springs.” Arkansas Gazette, June 25, 1972.

Standlee, Nora L. Davis. “Stories of the Civil War and Early Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. III, No. 3 (June 1957).

“The Stephen Foster of the Ozarks.” Carroll County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXIV, No. 1 (Spring 1979).

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie. “Cherokee.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

Terry, Dickson. “New Life for the Stair-Step Town.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 31, 1958.

Teske, Steven. “Green Forest (Carroll County).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

“Tornado Disaster In Arkansas.” Pathe newsreel, 1942. Getty Images, accessed September 2016.

“Tornado Hits Arkansas Town Killing 28 Persons.” Tuscaloosa [Alabama] News, October 30, 1942.

Tucker, Vernon. “Limestone part of Eureka Springs’ past and present.” Flashlight, September 1983.

Tyler, Virginia. “Around Town.” , Eureka Springs Times-Echo, November 11, 1982.

“Tyson Foods Proposes to Build Additional Plant in Arkansas.” Tyson Foods, April 14, 2016, accessed December 2016.

Vego, Jenny. “Crescent College and Conservatory.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed October 2016.

“Welcome to Eureka Springs!” Greater Eureka Springs Chamber of Commerce, accessed September 2016.

Westphal, June, and Catharine Osterage. A Fame Not Easily Forgotten: An Autobiography of Eureka Springs. Carthage, Missouri: Litho Printers and Bindery, 2010.

Westphal June, and Kate Cooper. Eureka Springs: City of Healing Waters. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2012.

Westphal, June, and Vineta Wingate. “Play Ball! A Little History of Baseball in Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly, Vol. LVI, No. 3 (September 2011).

Williams, Cindy. “Berryville.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, accessed September 2016.

“Working Together for Carroll County.” Eureka Springs Mayor’s Task Force on Economic Development, Greater Eureka Springs Chamber of Commerce, accessed October 2016.