Scenes of Madison County

Scenes of Madison County

Online Exhibit19th-Century Settlement

For a time the area now called Madison County was once the hunting grounds for the Osage Indians. But they were forced out as white settlement in the East pushed other Native American groups west. In 1838 about 16,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes, moving through Arkansas to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) along the “Trail of Tears.” Some 1,200 Cherokee and enslaved people followed the Benge Route through Missouri, down to Huntsville and beyond.

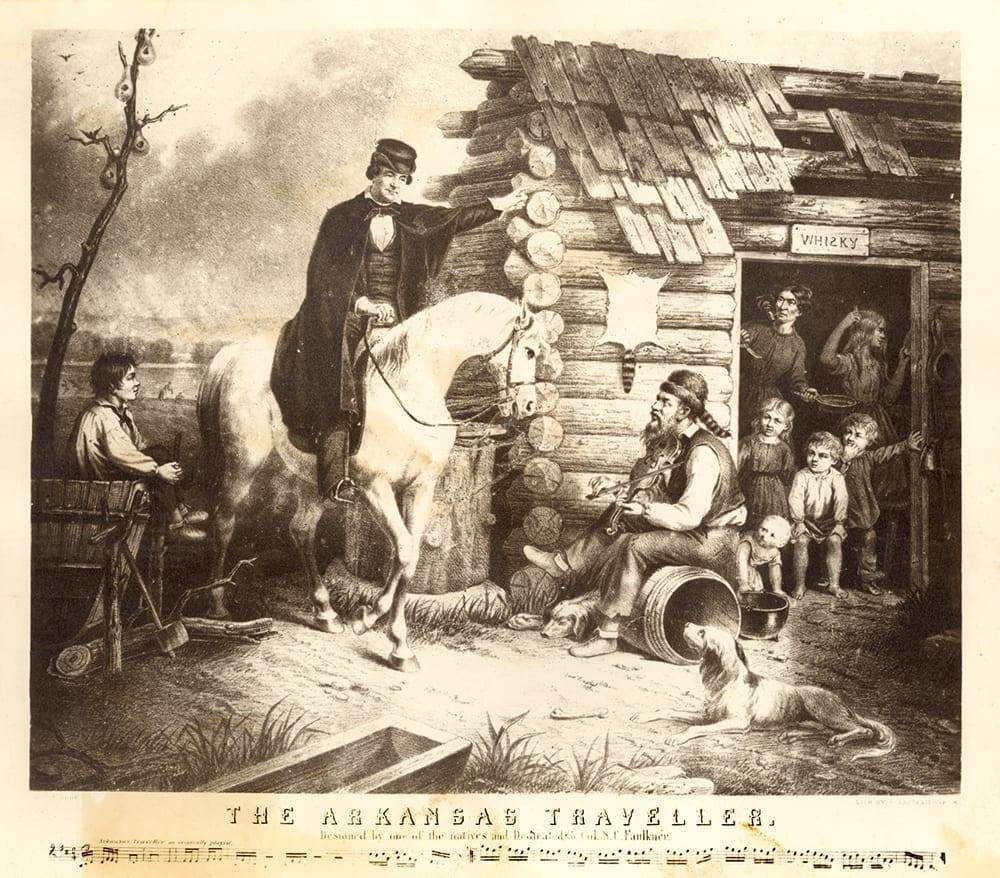

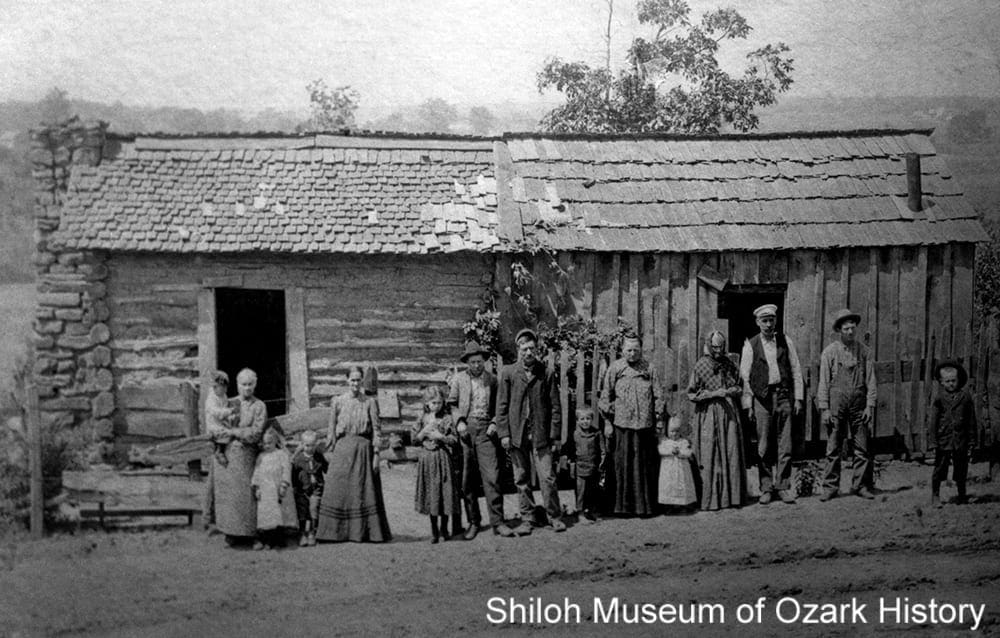

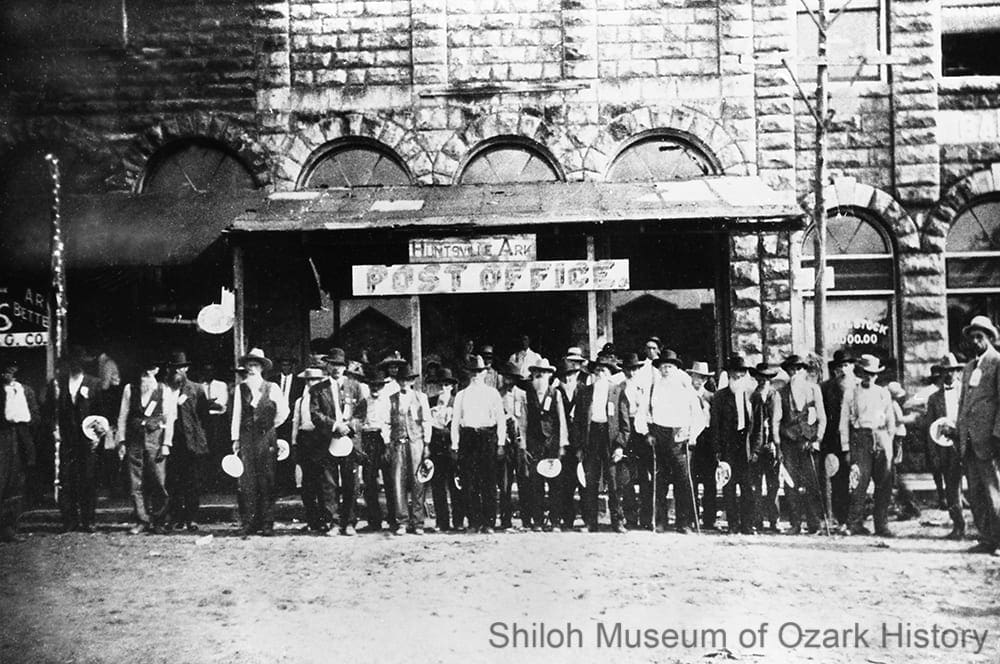

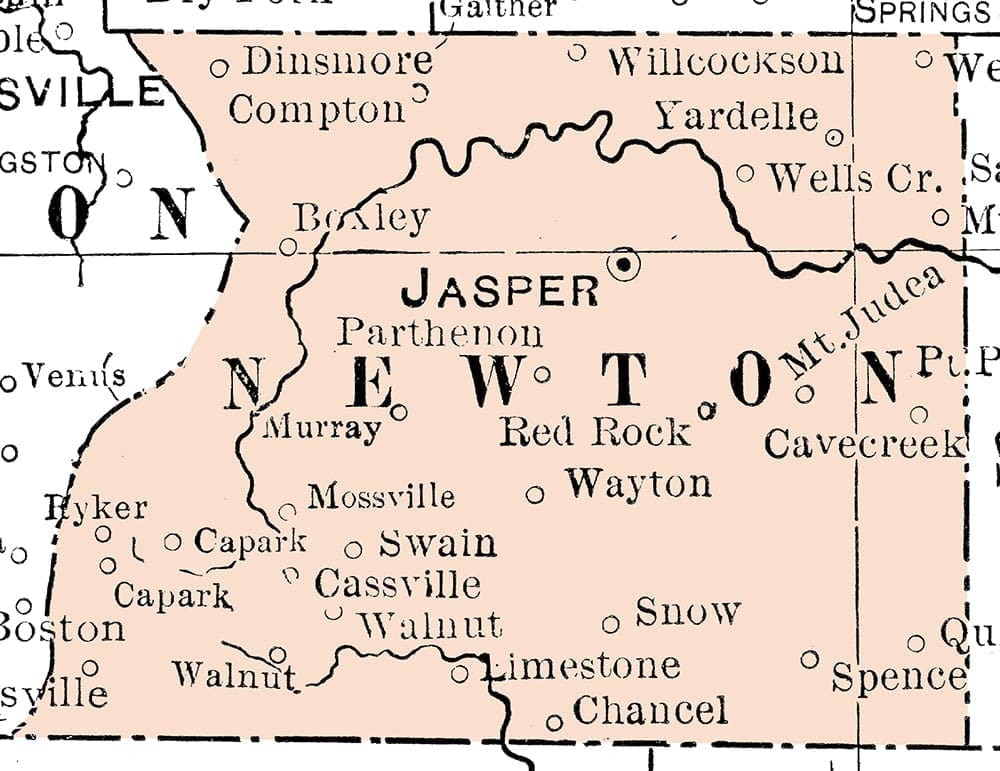

Madison County was formed in 1836, a few months after Arkansas statehood. Carved out of Washington and Carroll counties, it is said to be named for President James Madison by a group of settlers from Madison County, Alabama, home to the county seat of Huntsville. The county’s boundaries changed frequently early on, gaining land from Newton County and, at one point, stretching north to the Missouri border. Early settlers built log homes, farmed the land, established communities, and organized churches, schools, businesses, and governmental agencies. Some settlers brought enslaved people to work for them, but these African Americans were only a fraction of the county’s population. Still, families and neighbors split their loyalties during the Civil War over the issues of slavery and states’ rights.

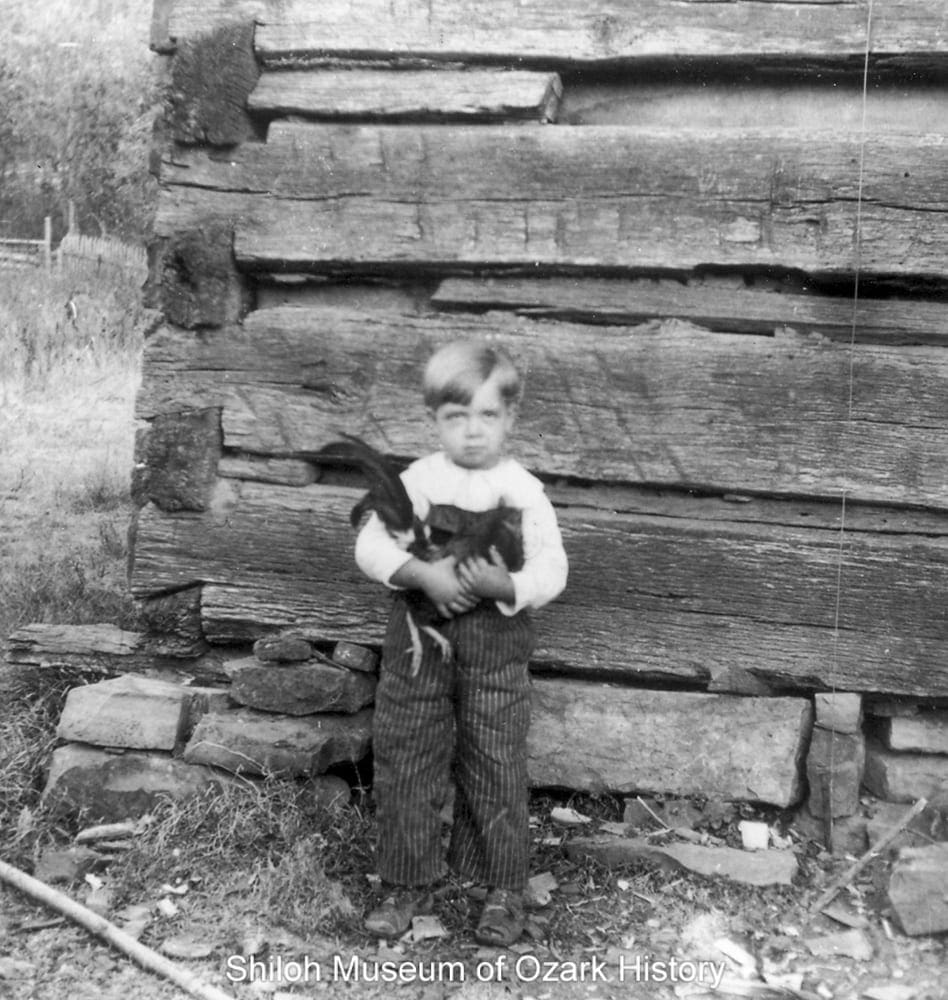

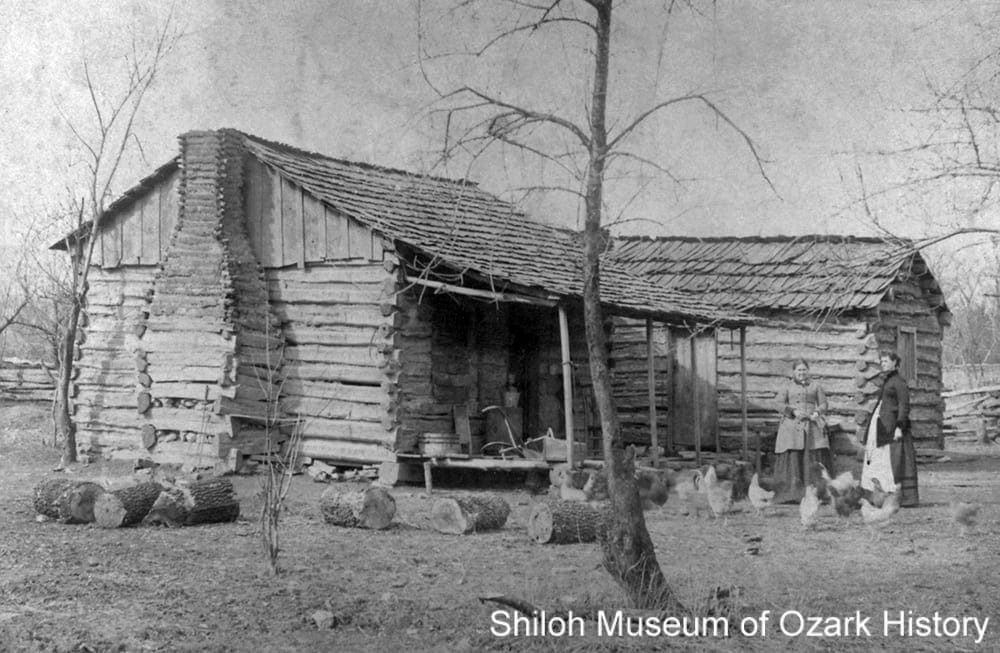

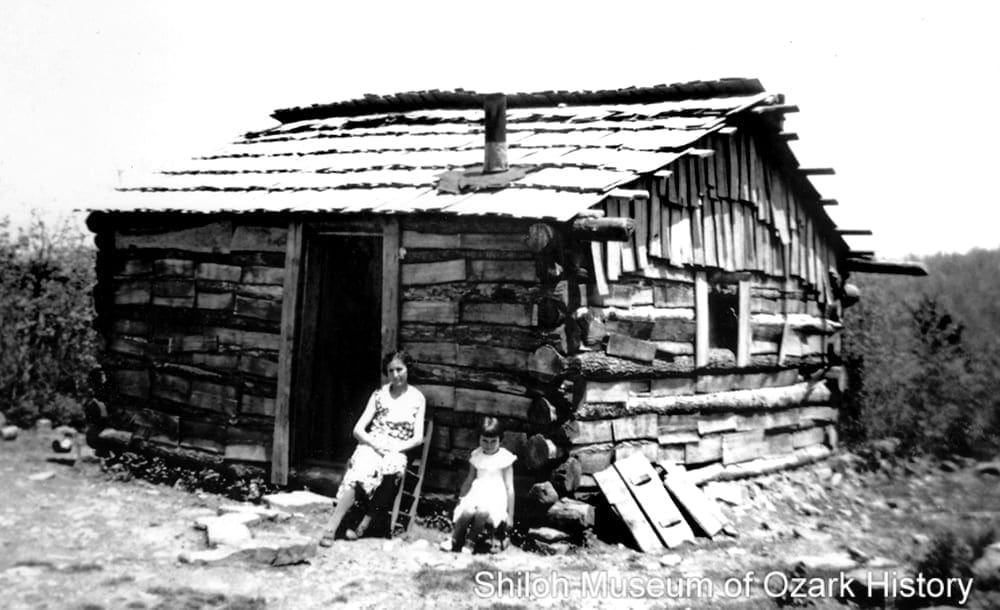

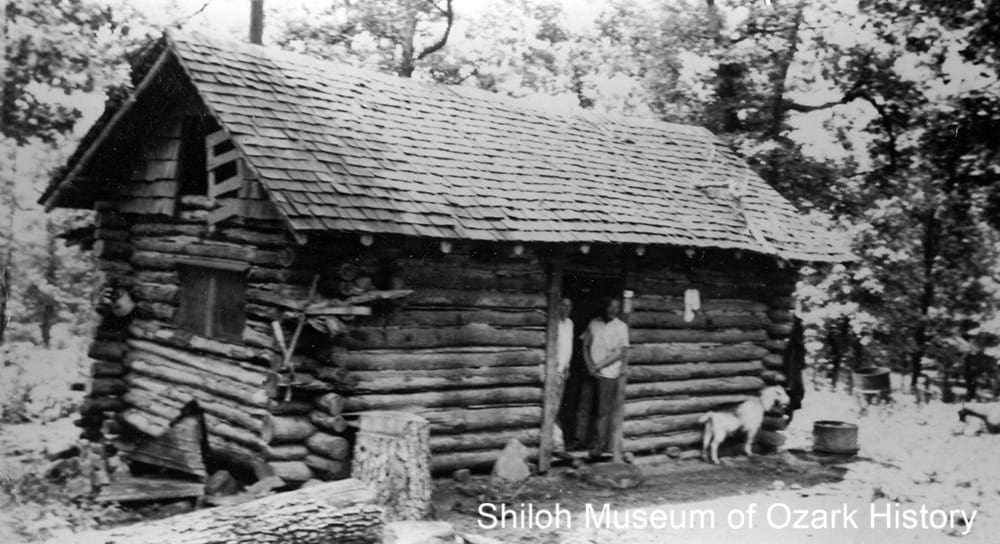

Old settlers’ cabin near Kingston, early-mid 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Hidy Bouher Eby, Butch Bouher, and Lota Dee Bouher Lagan Collection (S-2001-2-100)

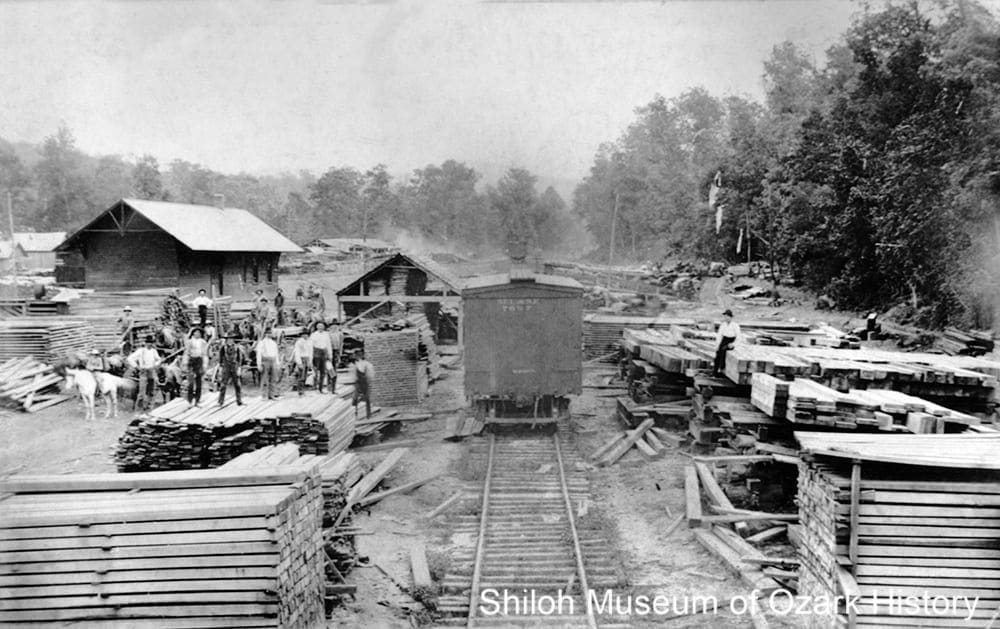

Residents slowly rebuilt after the war. While most were farmers, a new “crop” began to be harvested. Timber from old-growth forests became a major industry starting in the 1880s, when railroads began to be built throughout Northwest Arkansas, including what would become the St. Paul Branch of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad. As tracks were laid in the southern half of the county, old settlements such as St. Paul and Pettigrew turned into new boomtowns.

” . . . [W]e grew a little cotton for home consumption. There were not cotton gins in this section of the state 60 years ago and so we had to pick the seed out by hand, while mother would card, spin and weave. . . . In roasting-ear time, she grated corn for bread. She parched green coffee and us boys supplied the table meat by means of traps set in the woods. . . . We went bare-foot the year round and when our fire went out, it was my job to go across two 40-acre tracts to Uncle George Glenn’s and borrow fire, there being no matches.”

W. H. Wahlquist

Madison County Record, December 24, 1936

19th-Century Settlement

For a time the area now called Madison County was once the hunting grounds for the Osage Indians. But they were forced out as white settlement in the East pushed other Native American groups west. In 1838 about 16,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes, moving through Arkansas to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) along the “Trail of Tears.” Some 1,200 Cherokee and enslaved people followed the Benge Route through Missouri, down to Huntsville and beyond.

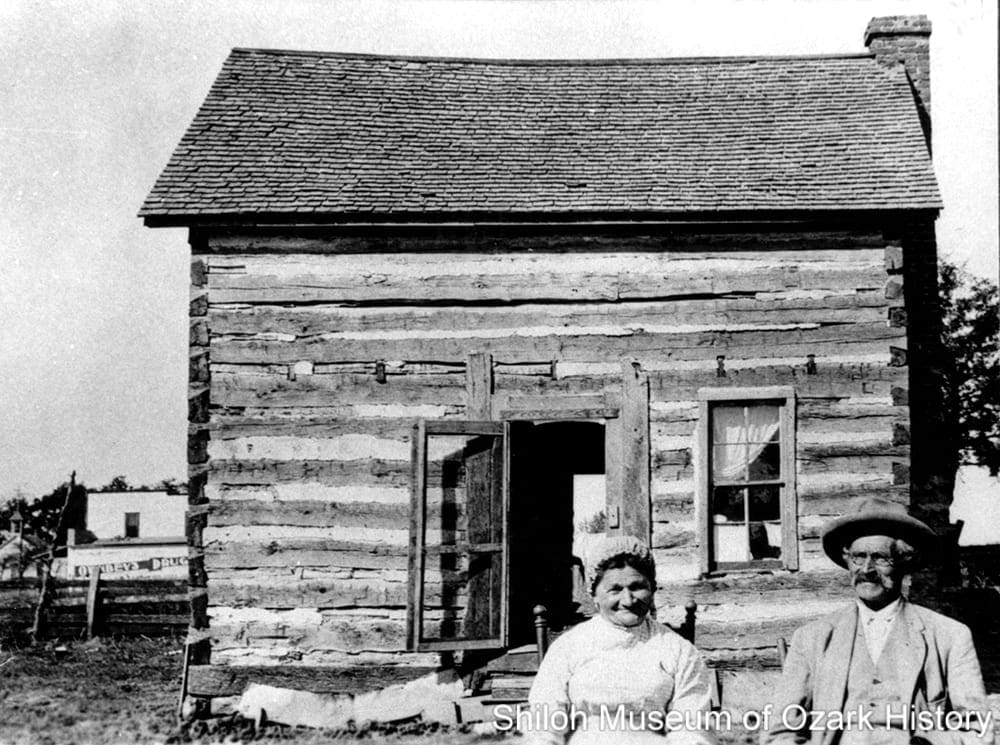

Madison County was formed in 1836, a few months after Arkansas statehood. Carved out of Washington and Carroll counties, it is said to be named for President James Madison by a group of settlers from Madison County, Alabama, home to the county seat of Huntsville. The county’s boundaries changed frequently early on, gaining land from Newton County and, at one point, stretching north to the Missouri border. Early settlers built log homes, farmed the land, established communities, and organized churches, schools, businesses, and governmental agencies. Some settlers brought enslaved people to work for them, but these African Americans were only a fraction of the county’s population. Still, families and neighbors split their loyalties during the Civil War over the issues of slavery and states’ rights.

Old settlers’ cabin near Kingston, early-mid 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Hidy Bouher Eby, Butch Bouher, and Lota Dee Bouher Lagan Collection (S-2001-2-100)

Residents slowly rebuilt after the war. While most were farmers, a new “crop” began to be harvested. Timber from old-growth forests became a major industry starting in the 1880s, when railroads began to be built throughout Northwest Arkansas, including what would become the St. Paul Branch of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad. As tracks were laid in the southern half of the county, old settlements such as St. Paul and Pettigrew turned into new boomtowns.

” . . . [W]e grew a little cotton for home consumption. There were not cotton gins in this section of the state 60 years ago and so we had to pick the seed out by hand, while mother would card, spin and weave. . . . In roasting-ear time, she grated corn for bread. She parched green coffee and us boys supplied the table meat by means of traps set in the woods. . . . We went bare-foot the year round and when our fire went out, it was my job to go across two 40-acre tracts to Uncle George Glenn’s and borrow fire, there being no matches.”

W. H. Wahlquist

Madison County Record, December 24, 1936

20th-Century Growth

Governor Bill Clinton speaking at the dedication of the Huntsville-Madison County Airport, September 27, 1986. Springdale News Collection (SN 9-27-1986)

Timber and commercial canneries were the biggest industries in the county going into the 20th century. By the Great Depression in the 1930s the timber was largely gone, along with many industry-related jobs and the railroad. County residents received aid in the form of jobs, training, and facilities through government-funded New Deal “make-work” programs and projects. In downtown Huntsville, two large barracks and a woodworking shop were built in the city park in 1939 by the National Youth Administration. Working in conjunction with the local school district and the State Vocational School, young men aged 18 to 25 were charged with building a $50,000 grade school as part of a skill-training program.

Electric lights came to downtown Huntsville in 1914, when a dynamo (generator) was installed at the Huntsville Roller Mill. The town was largely electrified by the late 1920s. It took the help of the federal Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to bring power to the rest of the county. To receive $200,000 in funding for the initial construction of 210 miles of power lines, in 1938 residents of Washington County and western Madison County formed the consumer-owned Ozarks Rural Electric Cooperative Corporation (now Ozarks Electric). Other towns like Kingston, Clifty, and Marble were served by the Carroll Electric Cooperation. As power lines came closer, eager folks had their homes wired for electricity. When the new gymnasium opened at the St. Paul High School, a newspaper ad for a basketball tournament exclaimed, “REA Lights!”

Many county residents left for work in California and other states during the Depression and World War II, with an additional 2,000 folks leaving in the decade following the war. Beginning in the 1940s roads and highways were built or improved, the work helped, in part, through the efforts of Madison-county native and 36th governor, Orval E. Faubus. Roads helped move merchandise and agricultural products to market and encouraged tourism. Livestock production became a major source of income after the war—first dairy cattle and then beef, followed by poultry as companies like Tyson Foods which relied on local growers to produce chickens and turkeys.

In the 1980s Huntsville was touted as a town on “the edge of an explosion.” A golf course and twenty-acre baseball park were built, a new airport opened, and the local Butterball turkey plant expanded its workforce. Measures were taken to fend off further school consolidation like the construction of a new high school.

“From all this it would seem that Rural Electrification for Madison County is ‘just around the corner.’ Now, let everyone get his shoulder to the wheel and ROLL, because it is going to take all hands and the cook to finish the job.”

Bert Jackson

Madison County Record, May 25, 1938

21st-Century Future

Today the county remains largely rural and agricultural in nature. In fact, it wasn’t until 2016 that the county’s first stoplight was installed in Huntsville. While neighboring counties generally have a declining birthrate, the county’s birthrate is the highest in the state, going from 10.7 births per 1,000 residents in 2011 to 14.8 births in 2018. Demographics are changing slowly. According to the 2010 census, ninety-three percent of the population was white, with the largest minority population of Latino origin at nearly five percent. Nearly nineteen percent of residents live below the poverty line. Recently there’s been a small influx of folks from Benton County, some of whom are leaving a higher cost of living for cheaper land.

While the timber industry is strong, the county’s largest employers are the Butterball turkey processing plant, the Huntsville School District, and Ducommun LaBarge Technologies, which manufactures circuit boards and electronic assemblies. But businesses are struggling on the Huntsville square. Factors include the relocation of Walmart away from downtown, the US 412 bypass around town, and online shopping. Many residents commute beyond the county’s borders to work, in some ways making the county one large “bedroom community.”

Tourism is on the rise. Miles of winding, scenic roads beckon motorcyclists, especially during the fall. The county’s four rivers—the White, Kings, Mulberry, and War Eagle—have their headwaters near the town of Boston. Along with those, nature-based resources such as Withrow Springs State Park, Ozark National Forest, Kings River Falls, Sweden Creek Falls, and the Ozark Natural Science Center offer places for hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, swimming, canoeing, and education.

“I hope it [business in downtown Huntsville] turns around. We have some good businesses down here—some unique things. I have regular customers that come all the way from Rogers. And they come about once a month, just for all of the little, quirky little shops and because our prices are so much better than the Springdale/Fayetteville areas.”

Pamela Montoya

Madison County Record, November 29, 2018

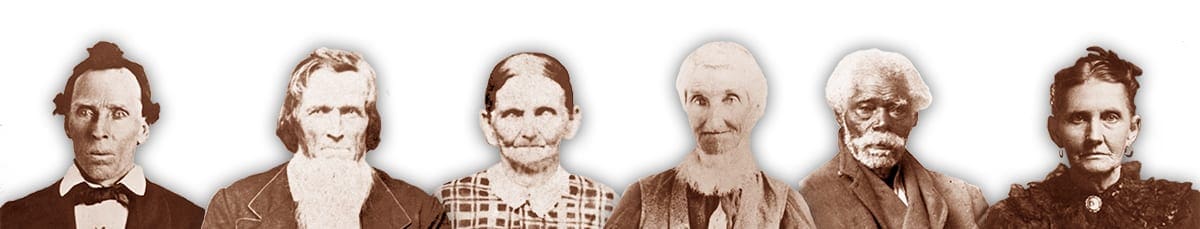

Settlers

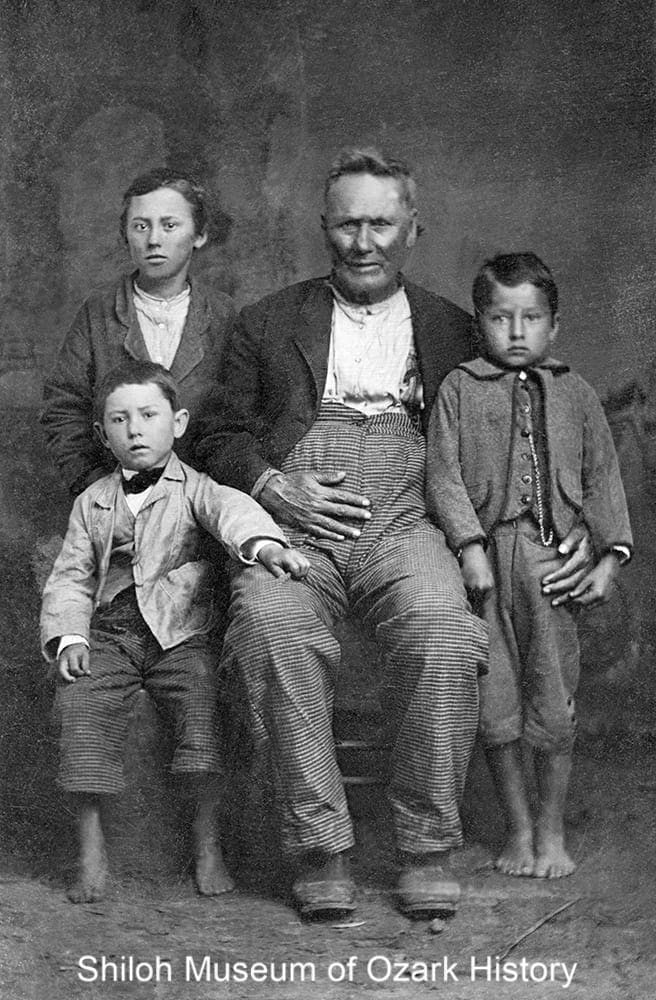

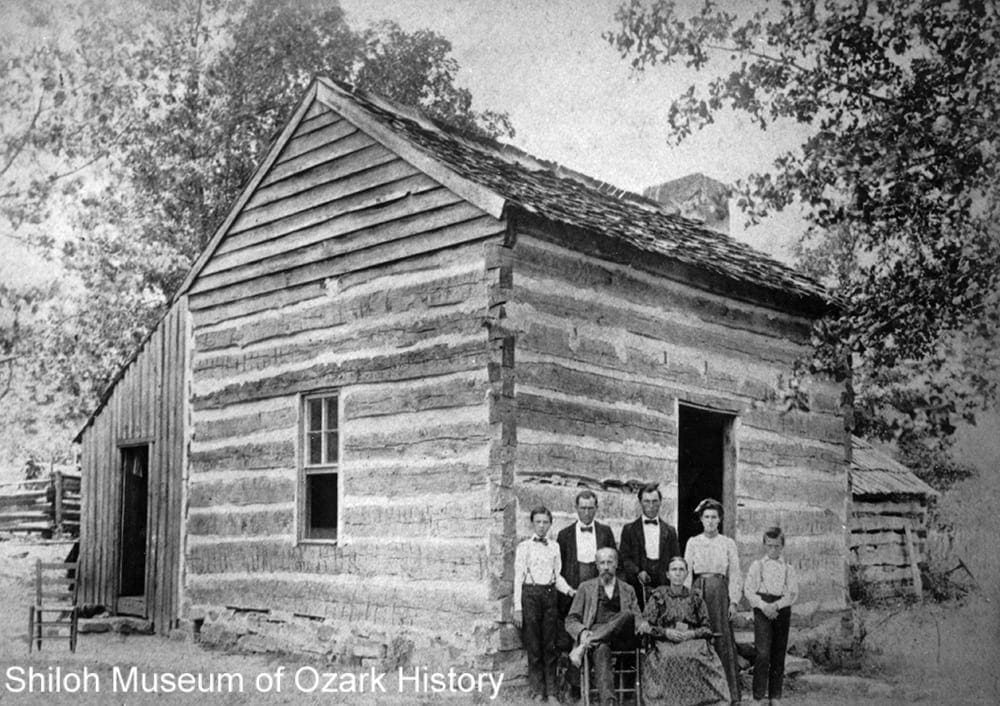

George Washington Vaughan with his grandsons, about 1881. Vaughan came with his family from Tennessee by 1830. Ada Lee Smith Shook Collection (S-2008-86-48)

Settlers began arriving in the late 1820s, generally traveling overland from Missouri or up the Arkansas River to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). Henry King was one of the first. He came from Alabama to scout out possible farm land, only to be killed when his wagon went over a cliff. In tribute, the Kings River was named after him. George Tucker explored the southwest part of the future county in 1827 with the Vaughan brothers, who settled Vaughan Valley near Hindsville in 1831. John Holmesley came with his family in 1828, after rumors spread about him being involved in the theft of a hog. “After hearing the story of his misdemeanor several times, he began to believe it and thought best to find a place to live elsewhere.

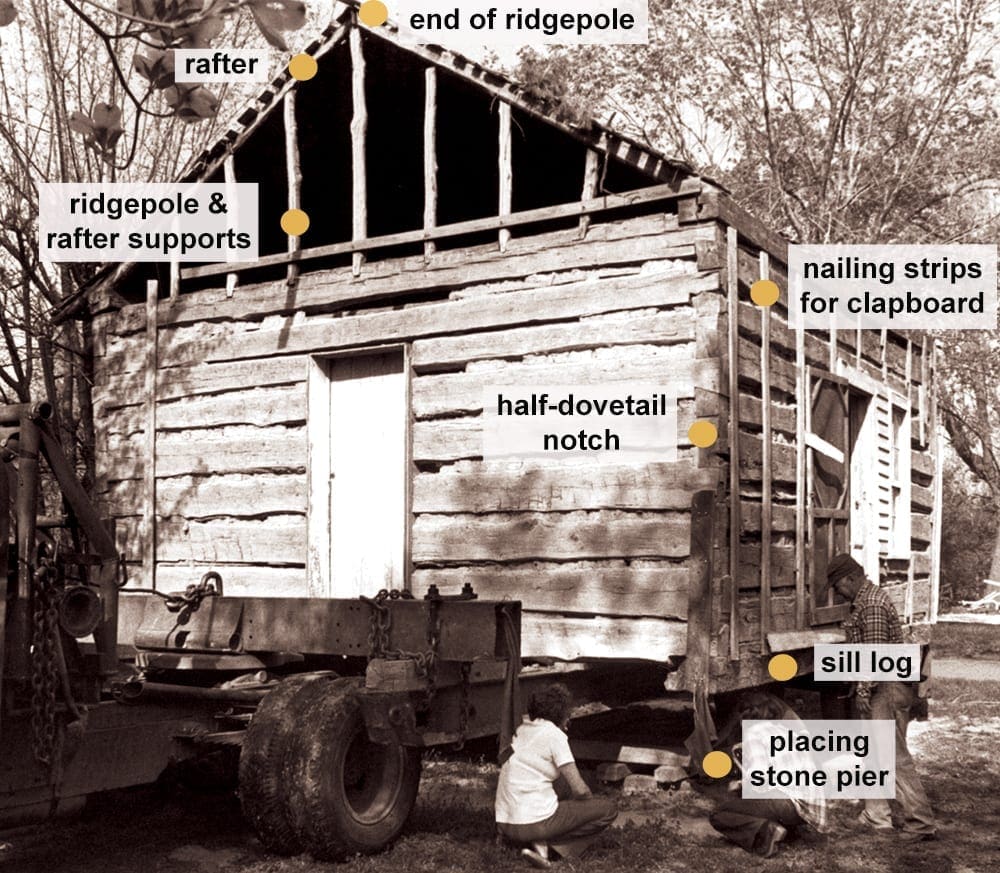

Early homes were usually built of hand-hewn logs with puncheon floors (half-round logs, with the flat side up). John Williams, who settled along the White River, was described as “a great trader who dealt largely in horses, slaves, etc.” By 1840 there were eighty-three enslaved workers in the county and 296 by 1860. Most did farm work, but a few were household servants. After the Civil War a little over half of the African-American population decided to stay in the county, many working for their former “owners.” By 1900 only forty-four blacks remained, many living in Whorton Creek Township, southwest of Huntsville.

Bruce and Joan Johnson with baby Jesse, Burrdog (left), and Sparky at their home under construction near St. Paul, July 24, 1974. Courtesy Bruce and Joan Johnson

A new type of settler came in the 1970s. They were young adults, seeking simpler, more meaningful lives by establishing small homesteads and communes. For some of these back-to-the-landers, living off the land was hard. Rural isolation, primitive living conditions, non-stop hard work, a lack of electricity and running water, and inter-group squabbles caused some groups like Yellowhammer, a women’s communal-living farm located near Patrick, to disband after only a few years. Others met the challenges and stayed on their land. Bob and Eileen Billig settled near Pettigrew in 1972 and did odd jobs like sign painting before building a business selling pressed-flower collages. They were part of the Headwaters School, formed in the early 1970s “to provide a balanced educational environment for rural students who were homeschooling.”

Gary Davidson and Cindy Cadwallader Davidson Arsaga with their homegrown vegetables at Glen Haught’s home, Witter, 1974. Nancy Marshall Collection (S-2013-58-17)

“It was in the year 1851 when we arrived in Madison County [from Tennessee] and all this world’s goods that my father and mother possessed when we got there was provision [food] enough to last us three days, one coon dog and 5 cts [cents] in silver. The town of Huntsville . . . contained a few business houses and several residences.”

E. B. “Ben” Hager

From a July 5, 1906, interview by Silas Claiborne Turnbo

Government

Madison County Courthouse, Huntsville, about 1937. This was the town’s fifth courthouse, built in 1905. Mr. and Mrs. Sherman Hinds Collection (S-87-63-14)

Before Huntsville became the county seat in 1839, county government operated out of a log barn on Evan S. Polk’s farm, close to the present Huntsville square. Six courthouses were built through the years, three of which burned down; one was abandoned due to poor construction. During the early 1900s there was continual talk of moving the county seat to the more populous St. Paul, the beneficiary of the area’s timber boom economy and the county’s only railroad. Some even suggested dividing the county into two. But as the timber industry began to slow in the 1920s, such talk died out. The current Art Deco-style courthouse of brick, concrete, and stone was built in 1939 by the federal Public Works Administration at a cost of roughly $150,000.

Madison County Courthouse, Huntsville, 1891. This was the fourth courthouse to be built, the only one made of brick. It was lost in 1902 when the part of the downtown square was destroyed by fire. Dorothy Ware Wilson Collection (S-83-147)

Madison County was home to two governors. Elected to represent Madison County during the state’s Secession Convention, Isaac Murphy famously voted against Arkansas seceding from the Union before the Civil War. He was appointed to serve as provisional governor in 1864, in the section of the state held by Federal forces, and later was elected governor statewide for one term. Orval E. Faubus served six terms, beginning in 1955, and is most remembered for blocking the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School. Both men’s homes were located on “Governor’s Hill,” just east of Huntsville.

The county went “dry” in 1946, meaning that the sale of alcohol was prohibited. In 2012 the group “Keeping the Money in Madison County” gathered enough votes to put the issue on the ballot. An opposing group lobbied against alcohol sales, worried that they would lead to safety issues. To illustrate their point, a wrecked car with a sign, “Your future with alcohol,” was towed around the county. The ballot passed and three new liquor stores opened in 2013.

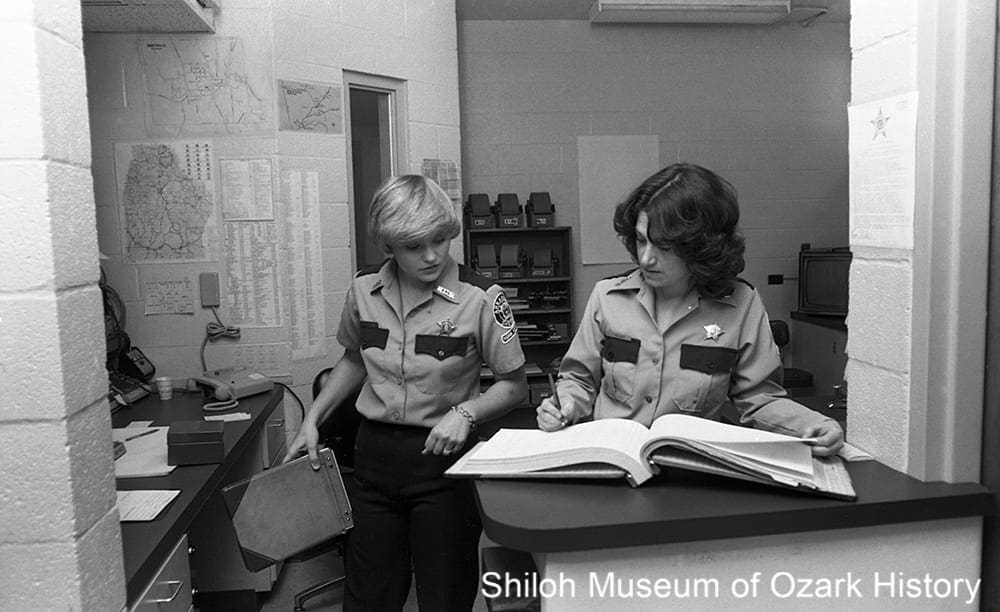

Madison County Jail employees, May 2, 1981. Morris White, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 5-2-1981)

Today Madison County and local city governments face economic uncertainty. While a highway bypass around Huntsville was hoped to spur business north of town, the results have been mixed. At the county jail in Huntsville, since prisoners can’t be held more than twenty-four hours, the county must pay to house them in neighboring counties. On three occasions voters rejected funding the renovation or construction of a new jail.

“While summer term was in session [in 1836 or 1837] a youth of 17 or 18 years of age was on trial for a serious offense. The trial Judge was in sympathy with the boy. While the court was in session the boy slipped through a crack in the back of the room. The Judge called to the boy saying ‘Run, damn you, run.'”

Oscar S. Johnson

Madison County Record, June 10, 1965

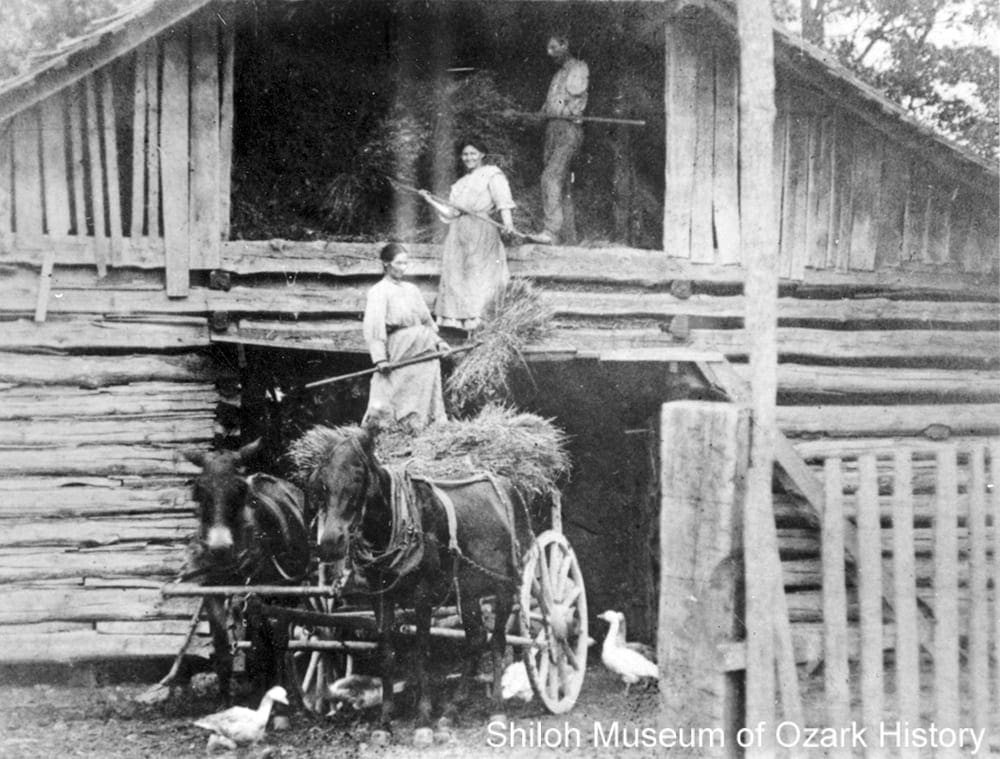

Agriculture

Turkey drive near Kingston, early-mid 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Hidy Bouher Eby, Butch Bouher, and Lota Dee Bouher Lagan Collection (S-2001-2-95)

In the 19th century most families grew what they needed to survive—things like corn, hogs, and vegetables. Some farmers grew cash crops such as tobacco and apples, but without easy transportation to get their product to market, they couldn’t make a business of it. The problem was solved in the mid-1880s when a railroad was built through the southern half of the county. By the 1900s turkeys were shipped by the thousands for the Thanksgiving market. In 1929 more than 1,200 birds were gathered “from Kingston to Marble, Alabam, and Huntsville.”

Garrett Williams (left) in his apple orchard with son-in-law Robert Bedford Wilson, Buckeye community (near Whitener), 1900s–1910s. Dorothy Ware Wilson Collection (S-82-209-10)

Farmers like Garrett Williams of the Buckeye community planted large-scale apple orchards. In 1903 he had one-hundred acres under cultivation and was putting in eighty more. A nurseryman as well, he grew and sold trees for other growers. He even shipped some of his apples to be exhibited at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. The region’s apple industry was so large that in 1907 a newspaper account enthusiastically valued the combined apple crop of Madison, Washington, and Benton counties at $2.5 million. In response, the Four Rivers Mutual Orchard Company near Red Star was organized around 1910. Investors bought thousands of acres of land, hiring locals to clear it and plant orchards. But insect damage and an unscrupulous land buyer forced the company to sell its assets a few years later.

After World War II many residents left, seeking better jobs. An “On the Farm Training” program for veterans began in Huntsville in 1946. It paid the men to learn such skills as how to build fences, deliver calves, clear land, weld metal, and treat cows suffering from milk fever. To further combat population loss and a decreasing economy, county leaders created a development plan. It included such endeavors as developing strawberry fields, establishing a grower’s association, and growing the dairy industry, whose producers sold milk to the Pet Milk plant in Huntsville.

Turkey processing at Swift Dairy and Poultry Company, Huntsville, 1974. Beatrice Foods Collection (S-86-122-39)

In 1974 Swift Dairy and Poultry Company opened a processing and freezing plant in Huntsville for its Butterball-brand turkeys. Back then, the 200-employee plant processed thirty birds a minute, or 150,000 pounds daily. Now known as Butterball LLC, the plant employs about 650 people and contributes much to the local economy. But the rise of poultry production has its cost. Tired of odor and fearful of water contamination, in 1989 residents near Clifty fought a winning battle against a sludge lagoon filled with poultry waste. In 2018 Butterball agreed to change how it dealt with wastewater, to reduce the unpleasant smell lingering over town.

Today, beef cattle and poultry are the county’s main agricultural industries, with farmers producing eggs and broilers for businesses like Tyson Foods. However some poultry growers have switched to raising beef cattle and harvesting hay, because, they say, the companies think their operations are too far from feed plants and processing facilities.

“As the timber disappeared, the people turned mostly to farming and raising cattle, but since the rugged hills would not support as many farmers and stockmen as it did timber workers, many had to leave and seek a livelihood elsewhere.”

Governor Orval E. Faubus

Ozarks Mountaineer, June 1957

Religion

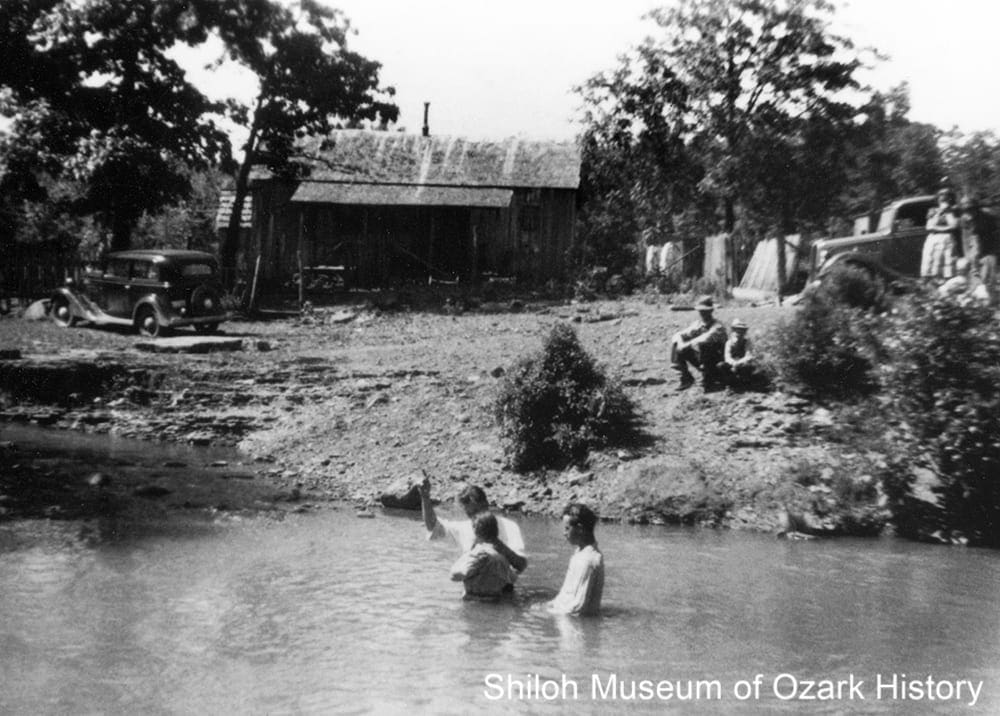

River baptism, Pettigrew, 1930s. With David Carlson (preacher, with hand in air), Elva Barker Martin, and Orville Martin. Wayne Martin Collection (S-86-83-1)

Established in 1833, the Kings River congregation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church was the first known religious group in the county. Since they arrived late in the year and didn’t have time to build homes before winter set in, the congregants set up a campground in a sheltered valley with a large spring, staying in wagons and lean-to structures. The area came to be known as Upper Campground and was used for many church gatherings over the years. Other early churches include the Big Fork Free-Will Baptist Church near Aurora, the (Primitive Baptist) New Hope Church near Kingston, and the Fairview Christian Church near Wesley. Some early preachers were circuit riders, traveling hundreds of miles by horseback to minister to a widespread group of congregants. Baptisms were frequently held outdoors, in a creek or river.

Kingston Community Presbyterian Church, mid-1920s. With Rev. Elmer J. Bouher (far right, with hands in pockets). Fred and Anna Berry Collection (S-84-113-23)

In the 1910s the Reverend Elmer J. Bouher of Indiana undertook a massive project to “improve” the lives of residents in rural Kingston. His “King’s Plan” involved building a church, school, and community building, improving local roads and farming methods, and teaching the principles of health and hygiene at a community medical clinic. Funded in part by the Brick Church in New York and local contributions of money, materials, and labor, the Kingston Community Presbyterian Church was begun in 1922. The project had its detractors, as some folks resented outsiders telling them how to live. Many factors contributed to the gradual decline of the project, including Bouher’s departure and the financial problems of the Great Depression. Use of the church and school buildings ended in 1948. The buildings were torn down three years later.

As religious needs expand, so do religious offerings. Begun in the 1990s, the Madison County Ministerial Alliance is a collaboration of ten to fifteen churches and religious organizations which hosts special religious services and collects food donations for a food pantry and the Pregnancy Center. In 2015, $4,920 was donated to families in need. St. John the Evangelist (Catholic) Church in Huntsville offers a Spanish-language mass for the county’s growing Latino population. The Madison County Cowboy Church was founded in 2010 to “[Serve] God the Cowboy Way.” Featuring a come-as-you-are attitude, the church’s sermons, country gospel music, and family-oriented dances and events may take place around a campfire or at the rodeo grounds. The Land of Infinite Bliss Retreat Center was built near Crosses in 2011 by the Tibetan Cultural Institute of Arkansas. The center offers classes on meditation, non-violence training, and Tibetan Buddhism.

“The great event of my visit was the church service on Sunday morning. . . . I preached as well as I could to an audience which included a large proportion of babies in arms and of restless little rascals who insisted on taking a walk in the aisles once in awhile . . .”

Dr. W. R. Taylor, “Our Investment in Arkansas”

Brick Church, Rochester, New York, June 1922

Civil War

Confederate soldiers reunion, Huntsville, 1913. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1423)

Prior to the Civil War, Madison County had relatively few enslaved workers as compared to several neighboring counties. The enslaved population barely grew from 1840, when three percent of residents were slaves, to 1860 at four percent. Like the rest of Northwest Arkansas, folks had divided loyalties. As war loomed on the horizon, schoolteacher, lawyer, and state senator Isaac Murphy of Huntsville was elected on a Unionist platform to serve at the Arkansas Secession Convention of 1861. He alone voted against leaving the Union. At first his fellow county residents approved of his action, but sentiments changed as the war came closer to home.

His life threatened, Murphy left for Missouri and joined the staff of Union General Samuel Curtis. Murphy made arrangements for his daughters to travel to Missouri as well, but two of them remained in Huntsville, where they were harassed continually. Perhaps their treatment led to the execution of nine men (one of whom survived) by Union soldiers in 1863. The soldier in command was arrested for his actions but the charges against him were later dropped.

While no major battles were fought in Madison County, there were a few small-scale skirmishes. Near war’s end, several hundred folks moved to four fortified “Union Colonies” set up at Huntsville, Richland, War Eagle, and Brush Creek. Meant to offer physical protection and a safe place to farm, the colonies were open to all who pledged allegiance to the United States. Lawless bushwhackers preyed on the county’s citizens even after the war. One legend has it that folks living in a valley near Hindsville were so tired of having their food carried off that they cleared the timber from the top of a hill and planted potatoes and other vegetables. According to the story, raiders never bothered “Tater Hill.”

“Shortly after [the battle at Prairie Grove] the Yankees came to Kings River and commenced their dreadful slaughter of men and horse stealing. Then there was raised in our settlement, independent companies of lawless bands who went about over the country, stealing and robbing every lady without distinction, and then after they got everything in our country, then turned in and burned our houses, turned out widows and orphans in the winter’s snow. They entirely robbed me out, never left me narry a single horse nor nothing that was worth anything.”

Jane Page

Kings River, November 14, 1866

Natural Resources

Howard Rufie Martin with his log truck, Pettigrew, about 1928. Wayne Martin Collection (S-85-322-48)

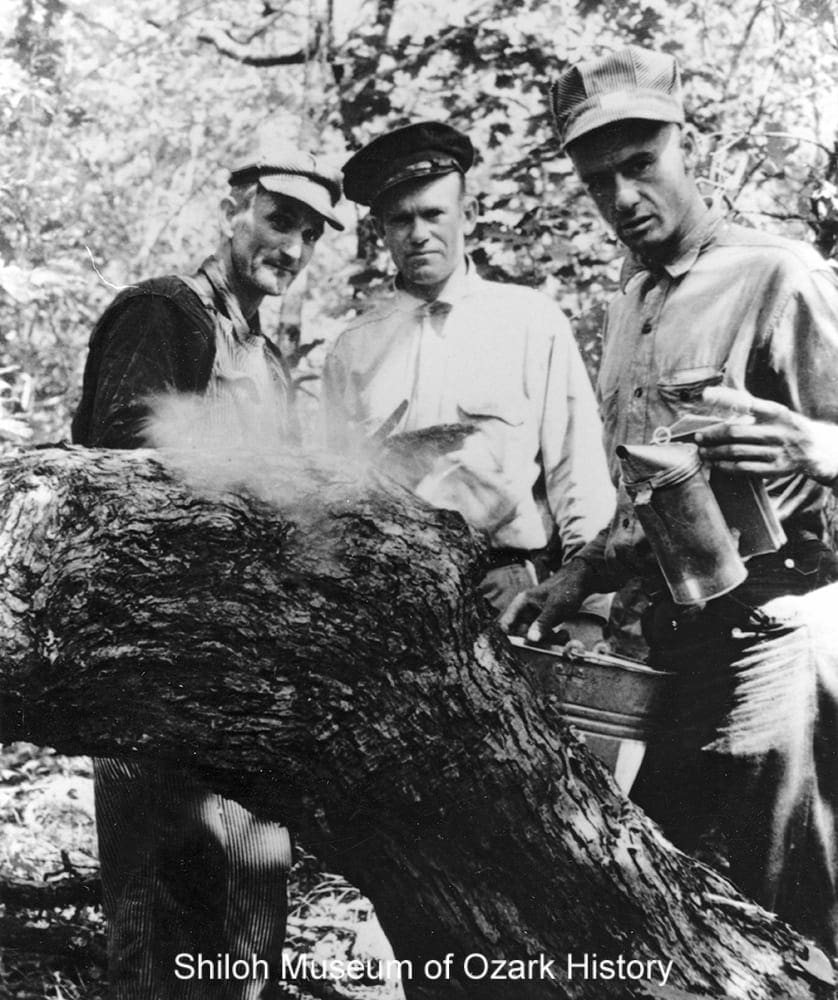

The county is heavily forested, with nearly two-thirds of the land covered by trees, even into the 21st century. A large portion of the southern section of the county is part of the Ozark National Forest, created in 1908 by President Theodore Roosevelt as a way to place its valuable hardwood timberland under government protection. The county’s timber industry was made possible when the first railroad branch line was built in the 1880s.

At one time, more lumber was shipped out of Pettigrew than anywhere else in the country. Three generations of the Martin family—Rufie, Orville, and Wayne—worked in the timber industry, cutting whatever wood they could sell and processing it at their sawmill near Pettigrew. Some of their work included white oak for railroad ties and wagon tongues (large poles used to connect a team of horses to a wagon), cherry for Singer sewing machines, and gum for bed rails made by Fulbright Wood Products in Fayetteville (Washington County).

As much profit as the timber industry brought to people and businesses, it also brought hardship. Working the timber was dangerous work and some men were maimed or killed in sawmill accidents. The influx of workers with ready cash encouraged saloons and brothels to spring up in the timber boomtowns. St. Paul’s longtime Frisco railroad agent, Mrs. J.M. Williams, recalled drunken fistfights between hundreds of men erupting on Saturday nights. The wholesale clear-cutting of trees led to soil erosion, which affected farms.

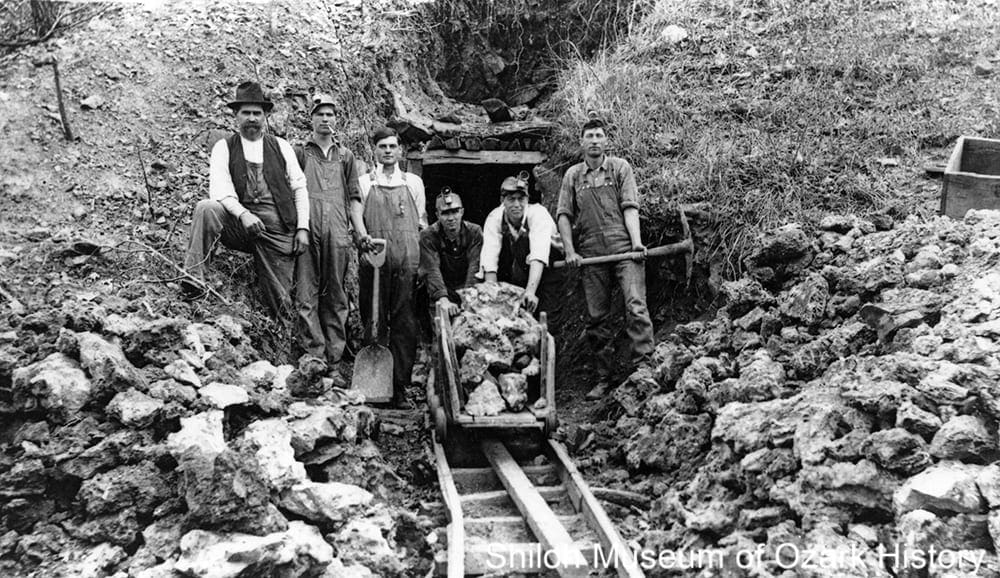

Carl Wright (near top of ladder) at his gold mine, Combs, 1918. Chloe Thomas Collection (S-97-1-215)

There have been several—largely unsuccessful—attempts to find other valuable resources in the county. Jasper H. Combs claimed that he had found a “long, lost Spanish [gold] mine” and the remains of a smelter on the Kings River, but nothing came of it. In 1918 Carl Wright sunk a sixty-foot mine shaft at Combs, looking for gold. Investors bought stock and the town’s population increased, but the venture failed a few months later. Wright tried again in 1933, paying miners $2 a day to haul, crush, and smelt rock in order to extract the metal. Only a few flecks of gold were found.

Oil and gas drilling tests occurred at Witter, Clifty, Huntsville, and nearby Georgetown from the 1920s to the 1950s. The most successful mining operation in the county was that of the War Eagle Lime Company near Huntsville. It excavated and crushed lime in the 1950s and 1960s for use as an agricultural soil amendment.

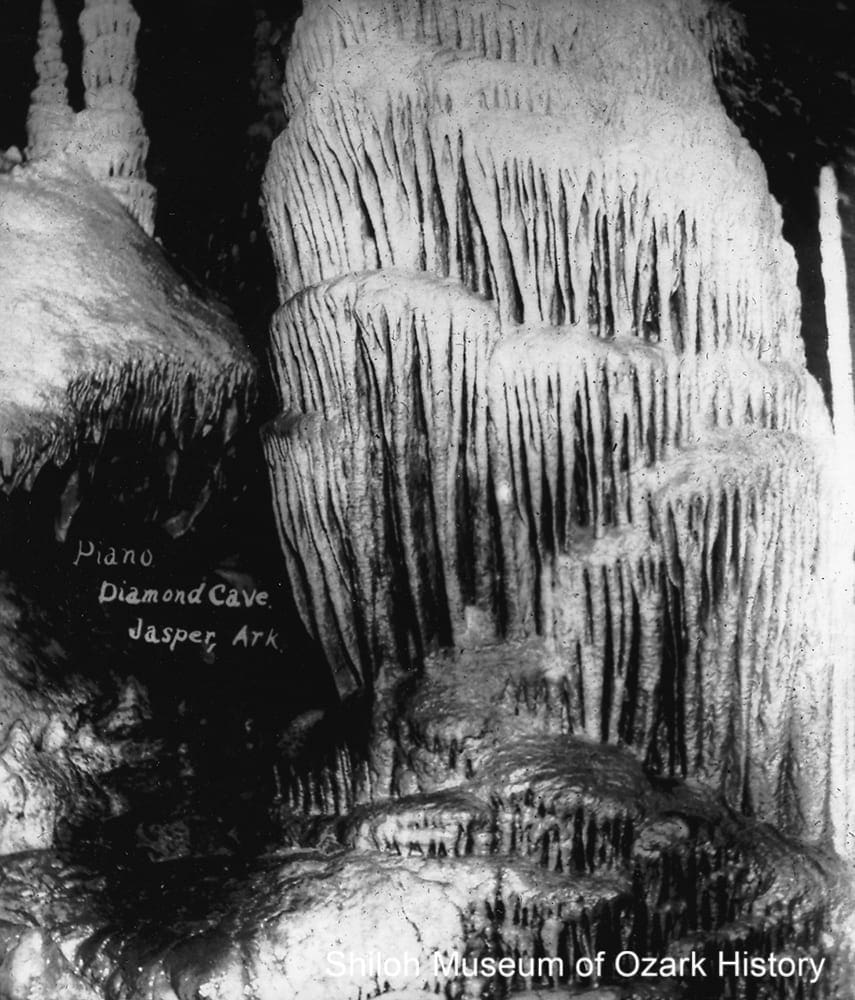

Girl Scouts at Camp Noark near Huntsville, June 1979. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 6-1979 #8)

The land itself is a natural resource for learning opportunities. In 1964 the NOARK (North Arkansas) Girl Scout Council purchased over 1,000 acres of land just north of Huntsville. When Camp Noark opened three years later, scouts learned such skills as how to take initiative and be self-reliant. As a way to learn resourcefulness, early campers made do with “lashing instead of tables, wood fire instead of stove, lantern instead of electricity, [and] singing instead of TV.” The Girl Scouts-Diamonds Council closed the camp at the end of the 2016 season because of high costs and declining use. However Girl Scout troops, church groups, and others can now rent the facilities, with the fees going to help maintain the camp. At the 15,000-acre Ozark Natural Science Center near Forum, students experience “hands-on and minds-on outdoor science education” by experiencing the “beauty and unique biodiversity of the Ozarks’ natural environment.” Developed by Ken and RuAnn Ewing and a small group of folks in 1989, the center now serves yearly over 3,000 students from Arkansas and Oklahoma. Specialty programs include yoga retreats, a Father’s Day camping weekend, eco-art, and caving.

Ken Ewing (right) at the Ozark Natural Science Center near Forum, December 11, 1992. Travis Doster, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 12-11-1992)

“Green Burgess and Luker [Luke] Carter were killed instantly about noon Tuesday near Wharton when the boiler of a sawmill, which they were operating, exploded. . . . Burgess was blown through the roof of the mill shed and his horribly mangled body fell only a few feet from where he had stood. . . . So terrific was the explosion that the boiler was blown about 25 feet from its base.”

Green Burgess’ obituary

Rogers Democrat, August 26, 1915

Business

St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad car at the Yount Stave Mill near the Frisco depot (far left), Pettigrew, 1900s. Mary Harrell Collection (S-99-17)

Water-run gristmills were among the first businesses in the county, grinding corn and wheat. Hawkins Mill on War Eagle Creek and the Withrow Mill at Withrow Springs were both established in the mid-1830s. The first steam-powered mill was built in 1881 by F. M. Sams in Huntsville for $6,400. It produced twenty barrels of flour daily. The Kingston Roller Mill was built by J. D. Basore Sr. and his sons in 1898. It took eight wagons to bring the heavy machinery from Springdale.

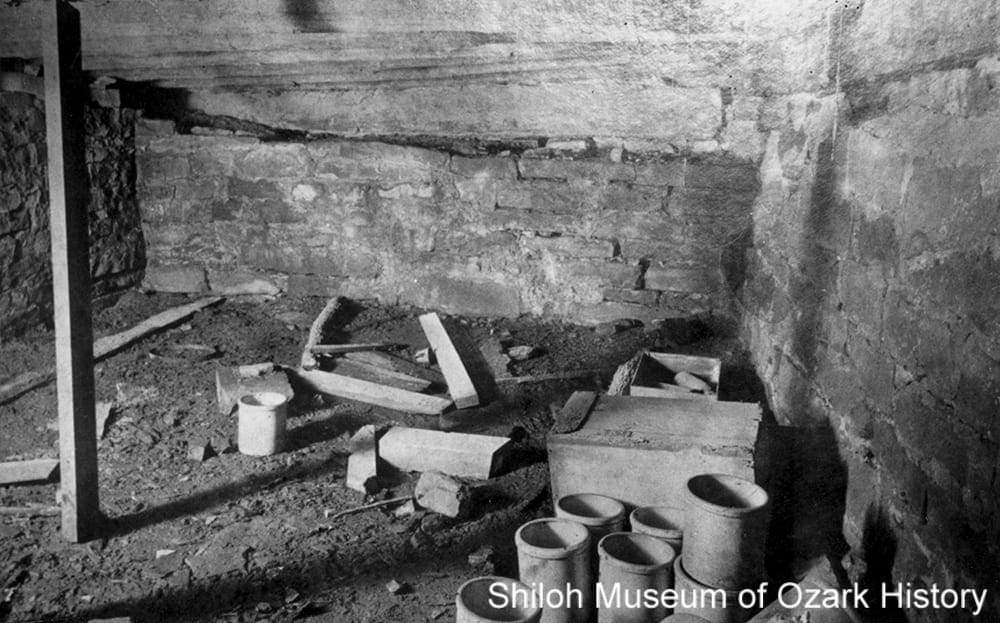

When Joel N. Bunch moved to Kingston in 1880, he opened a general store. But the poor roads and rugged terrain kept salesmen away. So he hauled his merchandise from Springfield, Missouri, sometimes taking three weeks to cover the over-200-mile-round trip. He also purchased materials gathered or produced by his neighbors. He sold mink, possum, and fox pelts to fur merchants, plants like goldenseal and ginseng to pharmaceutical companies, and honey and sorghum to his customers. Bunch began the Kingston Spoke Plant in 1907 and made wheel spokes for buggies and wagons for over twenty years. He also established and built the Bank of Kingston in 1911, complete with beautiful wood tellers’ cages and a vault advertised as “Fire, Mob, and Burglar Proof.” Today the building is home to Anstaff Bank.

For a long time the county’s industry and economy were tied to its forests. In 1887 the railroad shipped out 15,000 carloads of railroad ties and props for mine pits, valued at $2 million. One of the biggest players was the Phipps Lumber Company which, at its peak, received hundreds of wagons of lumber, barrel staves, and ties daily at its Pettigrew facility. At Drakes Creek, Noah Johnson manufactured about 40,000 wagon bows annually (woods supports used to hold up the canvas coverings of wagons). The timber industry still plays a role today, with at least seven major sawmills county-wide. The Richland Handle Company started in Delaney in the mid-1950s but moved to Wesley in 1964. It makes handles for such items as garden tools, shovels, and hammers. At St. Paul, Willhite Forest Products produces slats for shipping pallets, lumber for flooring, and railroad ties. The Royal Oak Charcoal plant near Huntsville uses waste slabs from sawmills to make charcoal for outdoor grills.

In 2016 the Huntsville Economic Development Commission created a plan to address local needs, including developing an industrial site, retaining and expanding businesses, and increasing tourism. Over in Hindsville, Arkansas Hemp Genetics had partnered with the University of Arkansas to study hemp flowers, a source of cannabidiol (CBD), a non-addictive substance that some believe has medical potential. But plans for a farm and production facility seem unlikely to come to pass.

“In 1919, [S. D.] Albright was the first man to order trucks to be used in the timber business [in Red Star]. Two GMC service trucks arrived in Pettigrew by train, but nobody knew how to drive them. However, after some practice, the men took the trucks to the woods with visions of returning loaded with wood. Gayle Edwards Eversole told me that instead, they returned with mules hooked to the front of the trucks because the trucks couldn’t pull the load.”

Wayne Martin

Pettigrew, Arkansas, Hardwood Capital of the World, 2010

Education

Schoolgirls from War Eagle township, early 1890s. From left, Stella Mae Brodie, Norah S. Routh (front), Jodie True, and Myrtle Routh. Mark Strube Collection (S-93-66-4)

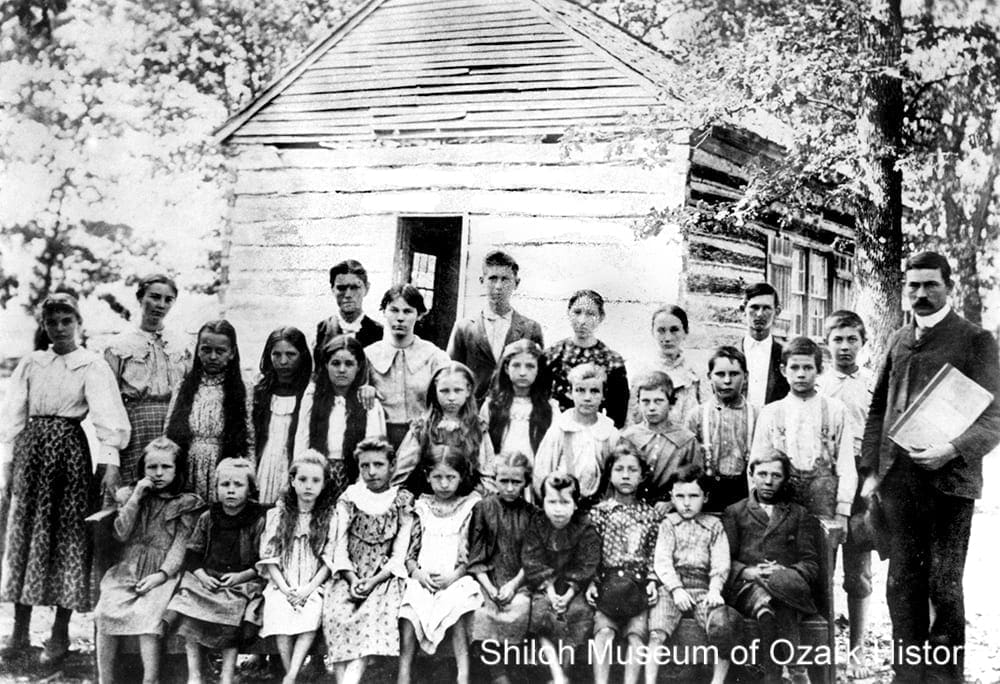

The county’s first school was said to have been built of logs on Sweden Creek in 1833, near present-day Kingston. Schools in Huntsville and old St. Paul soon followed. At the time there were no state-sponsored schools, only three-month-long, private subscription schools. The private Huntsville Masonic Institute, one of the first colleges in Arkansas, was built in 1855. The Pleasant View Female Seminary was chartered the same year, with five-month terms costing $8 each. The young ladies studied such subjects as history, grammar, spelling, and “mental arithmetic.” The former institution was run by future governor Isaac Murphy while the latter was run by at least two of his daughters. Both institutions closed in 1861 with the outbreak of the Civil War.

The first county school district was formed in Huntsville in 1868 and by 1897 there were 125 districts. In 1879 the county had 4,397 school-age children, but a little less than one-quarter were enrolled, with roughly half that amount (484) attending classes on any given day. There were a number of private and specialty schools during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Huntsville Academy offered grades one through eight as well as training for teachers. Jesse Bird organized the Hindsville Academy and later Bird College, a private high school in Huntsville.

In the 1920s the Kingston school came under the guidance of the Reverend Elmer J. Bouher, who was developing the large, progressive Kingston Community Presbyterian Church to “improve” the lives of local residents, in part through education. As school superintendent, Otto Ernest Rayburn worked hard to create a four-year accredited high school. The Huntsville State Vocational School opened in 1929 and trained students in life skills and trades such as “domestic arts” and agriculture. It was the first school in the county with indoor bathrooms, but there was one problem—the town didn’t have a sewer system. So the students’ first learning opportunity involved digging a hole for a septic system. In 1934 the school wanted to begin a football program, but there was opposition. In protest, students boycotted classes one day, going to nearby Governor’s Hill for a picnic. They won their battle. A team was formed, even though the school didn’t have uniforms or equipment. The players wore their overalls.

Whorton Creek School students and teacher, 1948. Back, from left: J. Mathis, Blenda Mathis (teacher), and LaVerne Cook. Front, from left: Joyce Mathis, Barbara Fowler, and Barbara Carlock. Courtesy Barbara Robertson and the Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society

Up until 1954 state laws mandated segregation between the races. Shady Grove School District (near Whorton Creek) was created by the Madison County Court in the early 1870s as a “colored school” for the children of those freed blacks who had stayed in the county after the Civil War. But by 1946 there was only one African-American child of school age, and setting up separate accommodation for her would have been costly. So Laverne Cook was quietly enrolled into the Lower Whorton Creek School where by all accounts she was treated like the other students, participating in all school activities for the year she attended.

The state’s large number of small, often rural school districts led, in part, to school consolidation, beginning in 1948. The plan was favored by the county board of education but not by parents, who wanted to keep their community schools. The county’s supervisor of schools received several threats against his life. But, with careful explanation and time, folks began to see the benefits of grouping funds and resources into a few schools. The county went from 122 school districts to two, with only one today. The Huntsville School District is geographically the third-largest in the state. It operates six schools in Huntsville and St. Paul. But enrollment is dropping, with some students transferring to Elkins, Springdale, and Fayetteville schools, all in Washington County.

“The Kingston High School is a school with a soul. . . . It is earnestly trying to meet the educational needs of a people typically American, in the unhampered environment of the beautiful Ozark Hills. . . . Its goal is to give to the youth of the mountain sector of Arkansas such an appreciation of beauty, such a thorough knowledge of principles, such a vision of things worth while that, having taken hold of the handles of the plow, they will not look back.”

Otto Ernest Rayburn and W. Gordon Ross

Ozark Life, Kingston, Arkansas, 1925

Transportation

St. Louis and San Francisco passenger train, Patrick, 1920s-early 1930s. James Bayles Collection (S-88-73-10)

The county’s vast hardwood forests were a magnet for railroad development. The first to be built into the county was the Fayetteville and Little Rock Railroad (soon purchased and expanded by the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad, the “Frisco”). In 1886 the initial line ran twenty-five miles southeast from Fayette Junction (Washington County) to Crosses, before pushing on to St. Paul and later Pettigrew by the end of the century. The short-lived Combs, Cass, and Eastern Railroad was built out of Combs by the J. H. Phipps Lumber Company of Fayetteville, to take advantage of a large stand of oak in nearby Franklin County.

The Frisco’s St. Paul Branch was important to the development of southern Madison County. Boomtowns and businesses grew along the line, including the timber and canning industries. Cash crops were shipped out as well, such as watermelon and tomatoes. By the 1930s the nation had entered the Great Depression. Much of the available timber had been cut down and the workers were gone, reducing the need for freight and passenger service. Without revenue, the railroad couldn’t afford to replace its worn-out infrastructure. The last scheduled train ran in July 1937.

Dedication of Highway 68, Huntsville Square, November 10, 1949. With future governor Orval E. Faubus (speaking) and Governor Sid McMath (seated, fourth from left). Gov. Orval E. Faubus Collection (S-90-48-37)

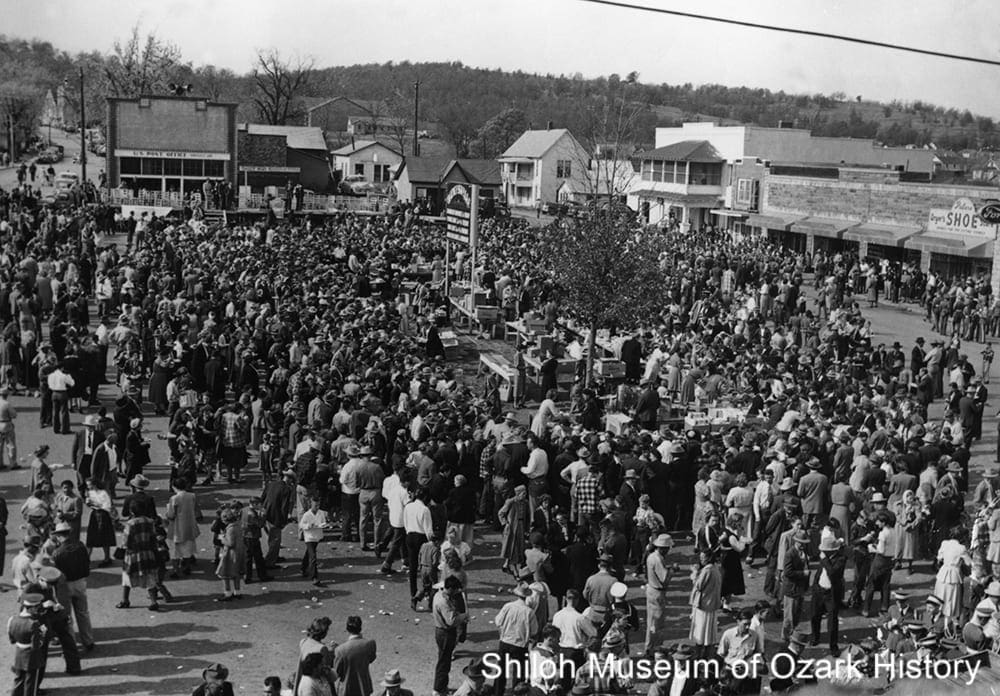

In the 1940s portions of Highway 68 (now Highway 412) west of Huntsville had yet to be paved. When the work was finished in 1949, a grand celebration was held in Huntsville. Thousands of residents, visitors, and dignitaries, including Governor Sid McMath, came together for prayers, speeches, a parade, a ribbon cutting, and a homemade lunch on the square for a crowd of nearly 5,000. In later years, Governor Orval E. Faubus, a native of Greasy Creek (near Combs), continued to improve or build area roads and highways, in an effort to make Madison County an important “crossroads” for Northwest Arkansas.

Highway 68 dedication community dinner with food tables in center, November 10, 1949. Golda Skaggs Collection (S-97-1-102)

Located on a shaved-off mountaintop at 1,748 feet above sea level, the Huntsville Municipal Airport is the highest airport in Arkansas. It was completed in 1986 with LaBarge Electronics in mind. The manufacturer of high-performance electronics needed a place for potential clients’ to land their corporate jets. Mayor Charles E. Coger led the effort to secure grants and other funding. He and others put in volunteer hours surveying the property, operating a bulldozer, and building a security fence.

“Remember, folks, bring enough [food] for yourself and some for our visitors [at the Highway 68 dedication]. . . . The least we can do for all our visitors is to feed them. That might look like a difficult job, but we know that when a Madison County housewife cooks an ordinary ‘dinner-on-the-ground’ meal, that it will feed at least two families beside her own. All we have to do is for each to do his own little part and there will be a super abundance.”

Orval E. Faubus

Madison County Record, November 3, 1949

Health

Kingston High School students exercising on the basketball court, mid 1920s. Rev. Elmer J. Bouher, photographer. Hidy Bouher Eby, Butch Bouher, and Lota Dee Bouher Lagan Collection (S-2001-2-124)

Doctors came to Madison County in the mid-1800s, some with college degrees, others having learned their craft by working with experienced physicians. Dr. George Counts started his forty-eight-year practice in Wesley in the late 1890s, visiting his patients first by horseback, then horse-drawn buggy, and later by car. He was said to have delivered two thousand babies. In Pettigrew, Dr. William Henry Mooney charged twenty-five cents to pull a tooth. Like most doctors, he took payment in the form of goods or labor, such as cured hams, horse feed, or a plowed garden. Mooney encouraged his son-in-law, Arthur Barker, to move his drugstore from Kingston to Pettigrew. The Mooney-Barker drug store opened in 1917, offering more than medicine over the years, including gasoline, poultry supplies, a soda fountain, bananas, and pawnbroker services.

Following the rapid rise of Eureka Springs (Carroll County) after the discovery of “healing waters” in 1879, other towns tried to establish their own health resorts. A two-story hotel and several cabins were built at Aurora on Grand Mountain, so patrons could take advantage of the Chalybeate Spring with its iron salts. In 1887 Hugh McDanield planned a hotel and spa at Big Spring near St. Paul, but died before construction could begin.

Beulah Frederick, a trained Red Cross nurse, came to Kingston around 1919 at the behest of the Reverend Elmer J. Bouher of the Kingston Community Presbyterian Church. It was part of his mission to see to the health needs of the community. Frederick taught hygiene to students and childcare to mothers, delivered babies, and ran a children’s clinic. A small health center began operating in 1926 with its first patient, a young man with typhoid. The standard treatment was medicine and three glasses of buttermilk daily. Healthful practices extended to the school as well, which had active exercise and sports programs for boys and girls.

Huntsville Memorial Hospital under construction, Summer 1950. Roy’s Photoshop, photographer. May Reed Markley Collection (S-84-155-108)

In 1949 voters approved the construction of a county hospital in Huntsville. With the passage of an $80,000 bond issue and donations of construction materials, equipment, and labor, and cash and furnishings supplied through local clubs, the twenty-one bed Madison County Memorial Hospital soon opened. But questions about finances and management plagued the hospital and it closed around 1954. Hometown native Dr. Austin Smith opened a clinic in the building and was largely responsible for reopening the hospital in the mid-1960s. He was on hand in 1980 for groundbreaking ceremonies for the new Huntsville Memorial Hospital. But financial problems persisted. The hospital closed in 1992.

Since then several clinics and health centers have opened their doors including the Boston Mountain Rural Health Center and the Madison County Medical and Surgical Group. The latter was begun by Dr. Tom Whiting in part with community support of $40,000 in fund raisers and funding and equipment from an anonymous benefactor. The Madison County Health Coalition began in 2000 with the goal to “maintain and seek local resources to achieve better health for our community.” A recent campaign featured high school students recording anti-tobacco radio ads. The Madison County Health Unit offers many services such as family planning, vaccinations, public health preparedness, and environmental health issues such as general sanitation, water-well testing, and West-Nile virus surveillance.

“‘Everybody drank likker [liquor] then but nobody got drunk,’ Uncle George continued, ‘My daddy made us kids drink a tablespoonful of whiskey every morning before breakfast to keep the chills off. . . . I didn’t like the stuff.'”

George Hogg Brashears (as quoted by Steele T. Kennedy)

Ozarks Mountaineer, August 1961

Disaster

Aftermath of the May 29, 1925, Huntsville fire. J. C. Hawkins, photographer. Lucille Phillips Collection (S-99-1-277)

Madison County has seen its share of disasters. Major droughts in 1854, 1874, and 1901 caused much hardship and crop destruction. In 1884 sheets of rain fell for six hours, flooding Hock and Cobb creeks. A cabin housing two families was caught in the torrent and floated downstream. While the men were able to escape through the roof, the eight people trapped inside were drowned. In 1886 a heavy snow left twenty-four inches on the ground. Several years later, folks in the Drakes Creek area experienced a “black snow,” where a layer of dirt covered about fifteen inches of white snow. It was so cold that winter that the snowfall didn’t melt until April.

County records were lost each time the courthouse burned. When Huntsville was set on fire by Union forces during the Civil War, the records were taken by the Union Army to Springfield, Missouri, only to be lost or destroyed. Kingston was also destroyed during the war. Much of downtown Huntsville was lost to fire on two other occasions in the early 1900s.

A 1945 tornado caused much devastation in the southern part of the county. In Crosses, only two buildings were left standing. At Japton, two women “were left sitting on a bed [uninjured] after the walls and roof had blown away.” A bolt of lightning hit a tree stump and blasted a large hole in the ground at Mt. Pleasant (near Whitener). In Aurora, nearly all the older buildings were blown down, including the school. At Wharton’s Creek “a valuable brood mare was blown a great distance” and had to be put down because of her injuries. In all, ten people were killed and many injured. Property damage was widespread, with about one hundred buildings destroyed.

“Not a thing could be salvaged [at the Sam Doss homestead in Marble]. The bodies of the mother and [her six] children were scattered promiscuously among the ruins. . . . The wind had whipped the clothing from their bodies, one of the children had been blown to the top of a bush. Keeping a strange watch over the place was the family dog, that walked in circles about the debris.”

Madison County Record, April 19, 1945

Recreation

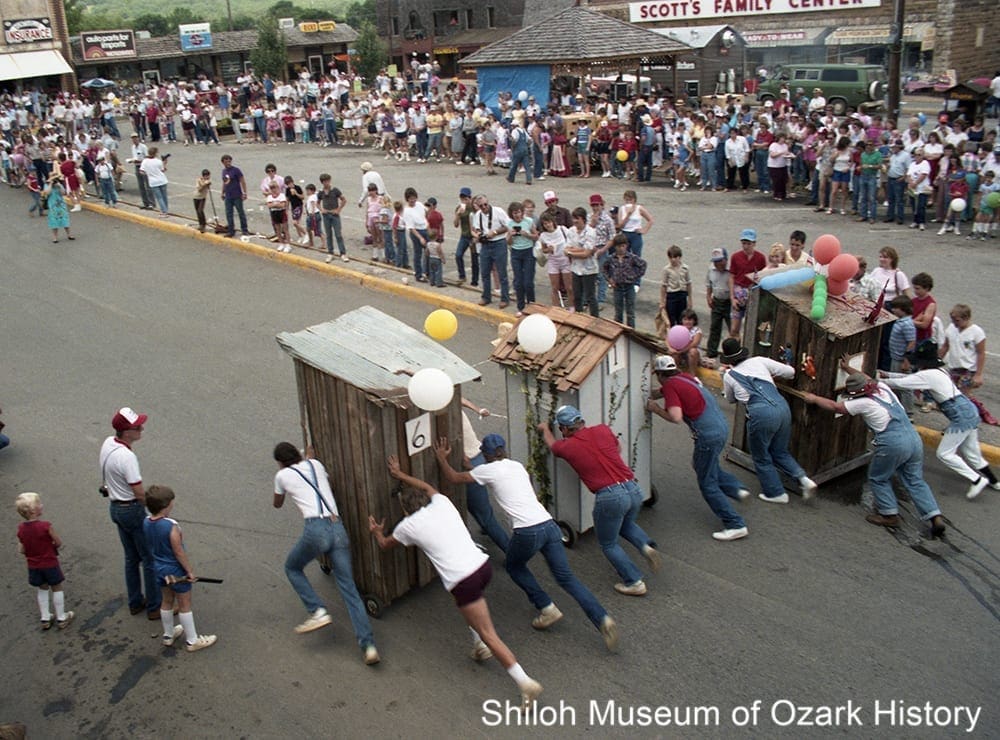

Outhouse race at Hawgfest, Huntsville, August 7, 1993. J. D. Watkins, photographer. Jay-Dee Studio Collection (86101)

Fiddlers contests were popular county-wide during the 1800s and up into the mid-1900s. Musicians competed in categories such as “old time,” stunt, jazz, or classical. Prizes included cash, merchandise, and services such as a sack of tobacco, a set of fiddle strings, or a “haircut, shave, massage, tonic, etc.” In 1926 seventy-seven-year-old John C. Calico of Drakes Creek was awarded the champion-fiddler title for Arkansas. During the 1920s and 1930s folks living in Marble gathered on the banks of the Kings River for fish fries. In 1929 a huge turkey and goose shoot was held in Huntsville, just in time for Thanksgiving. The tradition carried on there and in other communities like Alabam and Kingston for many years.

Rodeos were popular as well and included many offerings. At the two-day rodeo and picnic in Hindsville in 1927 there were speakers, races, ball games, a band concert, barbecue dinners, bronco-busting, and airplane stunt-flying by the Quinn-Willard Flying Circus. Huntsville held its first amateur rodeo in 1949. Organized by the Huntsville Riding Club, the event featured a parade with horse riders and floats and traditional rodeo contests such as calf roping and bull riding. In 1962 the new Sky-High Arena opened on Governor’s Hill. Today’s rodeo offers events for women, including barrel-racing and breakaway-roping.

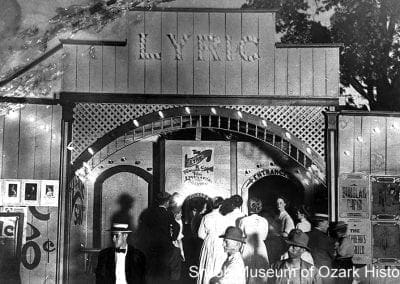

The Huntsville city park (now Polk Square) was the scene for many community activities during the 20th century. In the 1930s the park was home to turkey shoots, Easter egg hunts, celebrations of local veterans, political speeches, concerts, carnival rides and shows, Farm Bureau picnics, and reunions of former residents. In 1986 the Chamber of Commerce organized “Hawgfest,” a celebration held at the park and other venues. Over the years the event included food such as “Pig-Out Barbeques” and “Hawgdogs” and such activities as outhouse races, a rodeo, a golf tournament, arts and crafts booths, a “Hawgshoot” with muzzle-loading shotguns, music, a 5K run, contests for lip-syncing to songs, “hillbilly hawg-calling,” and the catching of greased pigs. The last festival was held in 2004.

“The canning factory at Delaney is almost completed. . . . A dance was given and two hundred and seventy-five people were present and most all took part in the dance. Even though some were opposed to this gathering, it was a very successful affair . . . there being not a bit of trouble from any cause.”

Madison County Record, April 25, 1925

Tourism

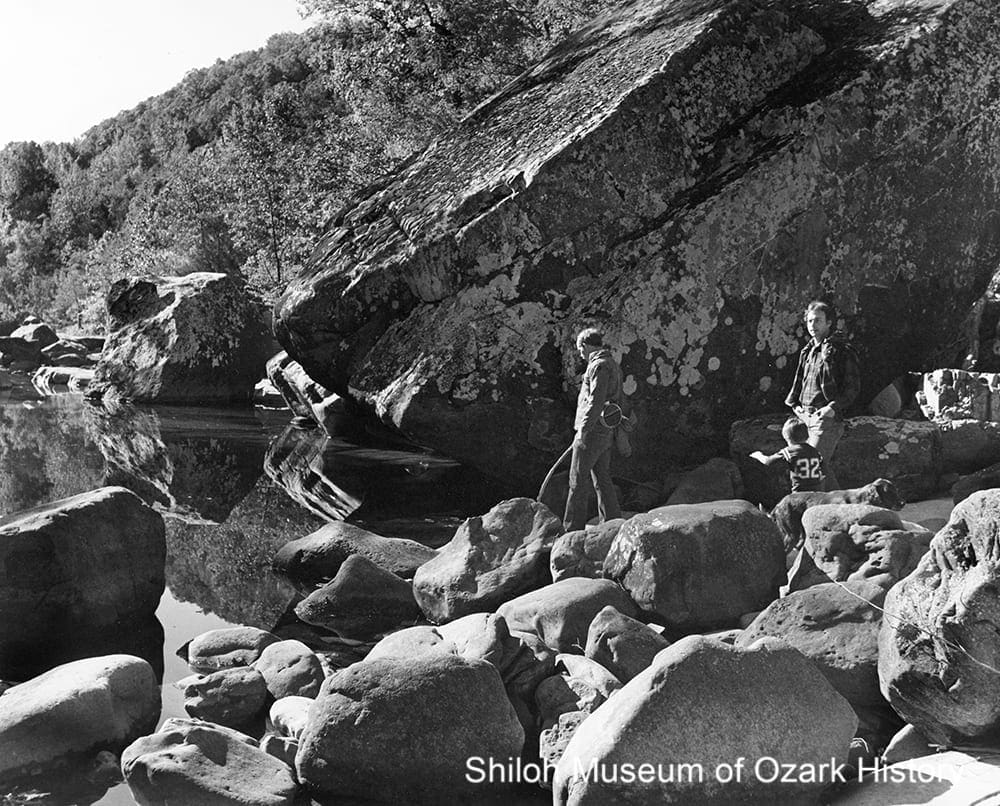

Visitors at Richland Creek, Ozark National Forest, Madison County, Arkansas, 1980s. Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism Collection (S-85-247-6)

Madison County became a member of the Ozark Playgrounds Association in the 1920s, a regional group out of Missouri which promoted tourism in the “Land of a Million Smiles.” Newspaper articles touted the charms of the county but also told about the need for better roads. Tourist camps were established in Kingston and Brashears Junction to meet the needs of the motoring public who wanted to stop and camp awhile. Although Huntsville leaders discussed creating such a camp, it appears that one was never built.

The Crossbowettes strike up a pose, Governor’s Hill, Huntsville, October 1962. From left: Beverly Alverson, Shirley Duncan Franklin, Susie McDonald Montgomery, Linda Owens Womack, Diane McKinney Johnson, and Juanita Thompson Shephard. Pat Donat, photographer. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT D-62-10)

In 1957 shooting enthusiast Arlis Coger worked to lure an annual crossbow tournament from Blanchard Springs in north-central Arkansas to Huntsville, donating land on Governor’s Hill for the festivities. Medieval-themed activities included costumed contestants, crossbow shooting, a queen and her court, and a banquet. The Crossbowettes, a high-school girls’ organization, performed archery tricks for an enthusiastic crowd. The tournament moved to Withrow Springs State Park in 1966, where the event’s pageantry lessened over time, only to resume again in the late 1990s as Renaissance festivals gained in popularity. The last tournament was held in 2003.

Swimming pool at Withrow Springs State Park near Huntsville, June 1968. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 7-1968-8)

Much of the county’s tourism is nature-based. Just north of Huntsville, Withrow Springs State Park opened in 1965, following a gift of land from timber baron Roscoe Hobbs. Featuring campsites, picnic areas, trails, and the county’s only public swimming pool, the park was a popular destination. Attendance has declined in recent years, especially with the 2018 closure of the pool because of repair costs. Other outdoor attractions include the Kings River Falls Natural Area near Venus, Sweden Creek Falls near Kingston, and the Ozark National Forest. The forest covers much of the southern part of Madison County, extending through sixteen counties in total.

The county’s small, winding roads through farmland and forests are a great draw for motorcyclists, especially in the fall. A few community events have popped up, including Huntsville’s first “Bluegrass and BBQ” event, which began in 2017. In Kingston, performers play in the downtown gazebo as part of “Music on the Square.” Realizing that tourism should be regionally based, rather than by city or county, Madison County economic development officials joined a 2012 initiative to brand four counties with the slogan, “Explore Northwest Arkansas.” A website includes such Huntsville attractions as the farmers’ market, Oakridge Golf Course, and Mitchusson Park Bike Course, designed for riders to hone their mountain-biking skills. Volunteers helped build several stunt features “designed to mimic natural elements found in the region.”

“The cotton pickin’ government is trying to take us over. . . . It’s already taken over the Buffalo (River). Now they’re trying to work down and take both sides of the Kings River. . . . Now they’re making the area a tourist attraction, so bureaucrats can come in here and lollygag and kick us out. I came out to here to get away from civilization, not to pile up in the middle of the big mucky mucks.”

Al Bergstrom

Arkansas Democrat, May 7, 1979

Credits

“Early Madison County Doctors Part 3,” Madison County Musings, Vol. XX, No. 1 (Spring 2001).

“How Noark Girl Scout Camp Program Began.” Special Collections, Mullins Library, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, circa 1970.

“Withrow Springs State Park.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 7-18-2018. (accessed 4/2019)

Abernathy, Donna. A Common Purpose: Powering Communities and Empowering Members, 1938-2013. Ozarks Electric Cooperative: Fayetteville, 2013. (accessed 4/2019)

Bernet, Brenda. “Square to draw from new bypass.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 6-21-2012.

Bowden, Bill. “Madison County to get its first stoplight.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 1-31-2016. (accessed 4/2019)

Burnett, Abby, Ellen Compton, and John D. Little. When The Presbyterians Came to Kingston: Kingston Community Church, 1917-1951. Bradshaw Mountain Publishers: Kingston, Arkansas, 2000.

Burnett, Abby. “Solid Waste, Water Projects Bring Madison County to 1993.” Springdale Morning News, 1-21-1993.

Cannon, Delores. “Huntsville: ’88 brought many business, civic improvements.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 3-19-1989.

Combs, Jasper H. “Claims Rich Deposits of Ore In Ozarks.” Madison County Record, 11-16-1950.

Community and Conflict: The Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks. “Madison County, Arkansas.” Springfield-Green County (MO) Library District, 2009. (accessed 3/2019)

Deane, Ernie. “Crossbowmen Gather for Tournament.” Springdale News, 10-11-1978.

Deane, Ernie. “Historical Relations of Two Madison Counties.” Undated and unsourced newspaper column.

Dornaus, Margaret. “Huntsville is coming to life.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 3-29-1987.

Dougan, Michael B. “Isaac Murphy (1799-1882).” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 2-11-2019. (accessed 3/2019)

Duggan, Thomas. “St. Louis and San Francisco-St. Paul Branch.” Unpublished manuscript, Shiloh Museum of Ozark History research files, 2014.

Dyer, Dorothy Roberts. “The Black Snow of 1894-1895.” Madison County Musings, Vol. XXI, No. 1 (Spring 2002).

Edmisten, Bob. “Land of Crossbow to Come Alive.” Springdale News, 10-3-1967.

Edmisten, Robert. “Legendary Town Lives On, Historic Store, Bank Remain Vital Cogs on Kingston Square.” Springdale Morning News, 4-19-2004.

Explore Northwest Arkansas. “New Mountain Bike Hotspots.” 8-30-2018. (accessed 5/2019)

Facebook. “Madison County Cowboy Church.” (accessed 4/2019)

Faubus, Orval E. “Huntsville’s Blessings, And Its Great Need.” Madison County Record, 7-11-1963.

Faubus, Orval. “A Great Day For Madison County.” Madison County Record, 11-3-1949.

Gearhart, Mary. “Thriving Huntsville the center of ‘Booger County.'” Northwest Arkansas Times, 7-25-1988.

Gittings, Misty. “Union Colonies.” Springdale News, 3-4-2012.

Haddigan, Michael. “’70s Refugees From Cities Leaving Hills.” Arkansas Gazette, 11-28-1983.

Haden, Rebecca, and Joy Russell. “Madison County.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 2-5-2019. (accessed 3/2019)

Harrington, Rod. “Assessor: Benton County residents moving to Madison County.” Madison County Record, 2-1-2018.

Harrington, Rod. “Butterball to reduce lagoon use.” Madison County Record, 9-6-2018.

Harrington, Rod. “Downtown merchants hopeful for change after tough year.” Madison County Record, 11-29-2018.

Harrington, Rod. “Hatfield: Huntsville ‘making progress’ economically.” Madison County Record, 2-1-2018.

Harrington, Rod. “Living with liquor in Madison County.” Madison County Record, 11-25-2018.

Harrington, Rod. “‘We’re desperate,’ Officials, residents plead with lawmakers to address jail problems.” Madison County Record, 2-1-2018.

Hatfield, Kevin. “Huntsville Massacre.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 6-19-2018. (accessed 3/2019)

Hatfield, Kevin. “Kingston School.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 2-3-2012. (accessed 3/2019)

Hatfield, Kevin. A Chronological History of Huntsville, Arkansas. Madison County Genealogical and Historical Society: Huntsville, 2013.

Hatfield, Kevin. The History of Education in Madison County, Arkansas, 1827-1948. PhD diss., University of Arkansas (Fayetteville), May 1991.

Head, Kenneth. “Girl Scouts to close four camps.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 2-27-2016.

Headwaters School. “The Short History.” (accessed 4/2019; no longer available 3/2020))

Hebda, Dwain. “Cowboy Churches.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 1-29-2019. (accessed 4/2019)

Heuston, John. “Withrow Spring Still Soothes the Weary Traveler.” Springdale News, 2-17-1966.

Huntsville Republican. “Huntsville To Have Electric Lights.”12-3-1914. Reprinted in Madison County Musings, Vol. XXX, No. 4 (Winter 2011).

Huntsville School District. “Huntsville Public Schools.” (accessed 4/2019)

Jackson, Bert. “Drilling Crew Starts Search for Oil on Hargis Farm East of Huntsville.” Madison County Record, 4-3-1952.

Johnson, Oscar S. “Early History of Madison County.” Madison County Record, 6-10-1965.

Johnson, Oscar. “Oscar Johnson Records Madison County History.” Madison County Record, 9-25-1986.

Kennedy, Steele T. “Historic Madison County Becomes the Country of Tomorrow.” Ozark Mountaineer, Vol. 5, No. 8 (June 1957).

Kennedy, Steele T. “‘Old Skully:’ Famous Landmark in the Boston Range.” Ozarks Mountaineer (Vol. 39, Nos. 6 & 7, August 1991), as quoted in Madison County Musings, Vol. XX, No.1 (Spring 2001).

Laking, George. “History of the Withrow Renaissance Festival.” Withrow Faire, 1998. (accessed 4/2019)

Lehovec, Bettina. “Buddhists Dedicate Center.” Benton County Daily Record, 10-29-2011.

Littrell, Ellery. “$4,200 Pledged to County Hospital by Personal Notes; $2,000 Needed.” Madison County Record, 3-5-1953.

Madison County Musings. “Early Madison County, Arkansas Doctors, Part 8.” Vol. XXVI, No. 1 (Spring 2007).

Madison County Musings. “Some Madison County Doctors.” Vol. XVII, No. 1 (Spring 1998).

Madison County Record. “2,000 Persons Attend Rodeo.” 11-28-1949.

Madison County Record. “Barbecue, Two Big Days” ad, 7-14-1927.

Madison County Record. “Bit of Kingston History: The Brick Church, Rochester, New York, 1924, More Lobbying.” 7-12-1990.

Madison County Record. “Board Recommends Sale Of Madison County Hospital.” 3-17-1966.

Madison County Record. “Closing Of Huntsville Hospital Imminent.” 12-24-1992.

Madison County Record. “Combs gold mine.” 6-17-2004.

Madison County Record. “Coming of Swift Plant Means Goal Is Reached.” 8-31-1972.

Madison County Record. “Concerned Citizens Seek Answers From Hospital Board.” 3-19-1992.

Madison County Record. “Construction Begins on Madison County Memorial Hospital.” 9-22-1949.

Madison County Record. “The County Hospital Project.” 5-12-1949.

Madison County Record.” Crosses Community.” 6-9-1938.

Madison County Record. “Dr. Smith Turns First Shovel In Ground Breaking Ceremonies.” 1-31-1980.

Madison County Record. “Fiddlers Contest Announced For Huntsville Reunion.” 7-21-1927.

Madison County Record. “The Georgetown ‘Free Oil’ Field.” 10-14-1948.

Madison County Record. “Greatest Celebration In Huntsville’s History.” 11-10-1949.

Madison County Record. “Hawgfest News.” 3-27-1986.

Madison County Record. “Highest Airport in State Dedicated.” undated (June 1986).

Madison County Record. “Hospital Investment Plan Discussed At Rally Tuesday.” 8-24-1950.

Madison County Record. “Latest Oil News.” 5-23-1929.

Madison County Record. “Lime Company Working Again on Highway 68.” 9-25-1952.

Madison County Record. “Madison County Hospital Changes Name,” 2-6-1975.

Madison County Record. “Madison County Hospital Will Remain Open, Doctors Staying,” 1-15-1953.

Madison County Record. “The Madison County Memorial Hospital—To Grow Or To Die.” 8-20-1953.

Madison County Record. “Madison County Unit of Ozarks Playgrounds.” 11-14-1929.

Madison County Record. “Madison County Voters Approve Hospital Plan.” 7-14-1949.

Madison County Record. “New Hospital To Open Doors Monday, October 2.” 9-28-1950.

Madison County Record. “NYA Resident Training Project Co-Sponsored by Public Schools.” 10-19-1939.

Madison County Record. “Oil Drilling Gets Started in Clifty Area.” 8-4-1949.

Madison County Record. “Oil Drilling in Progress on Two Wells Near Georgetown.” 7-15-1948.

Madison County Record. “Old Fiddlers Contest Proved Big Attraction.” 3-25-1926.

Madison County Record. “One Man’s Opinion On a Community Problem.” 3-15-1951.

Madison County Record. “REA Celebration, Kingston, May 10.” 5-2-1940.

Madison County Record. “Rural Electrification Now Fact for Madison County.” 5-26-1938.

Madison County Record. “Should Better Acquaint Selves With Electrical Use.” 6-2-1938.

Madison County Record. St. Paul High School basketball tournament ad, 3-28-1940.

Madison County Record. “Stave Market for Beer Barrels.” February 1933, reprinted in Madison County Musings, Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (Fall 1999).

Madison County Record. “Sutton Resigns As Hospital Board Head.” 1-1-1953.

Madison County Record. “Tomato Growers Dance.” 4-25-1925. Reprinted in Madison County Musings, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Fall 1989).

Madison County Record. “Tornado—Worst Disaster in Madison County History.” 4-19-1945. Reprinted in Madison County Musings, Vol. XII, No. 1 (Spring 1993).

Madison County Record. “Turkey Shooting Match to Become Annual Event.” 11-21-1929.

Madison County Record. “Turkeys Shipped By Thousands From County.” 11-14-1929.

Madison County Record. “Work on Highway 68 Spans Four Administrations.” 11-3-1949.

Martin, Wayne. Pettigrew, Arkansas, Hardwood Capital of the World. Shiloh Museum of Ozark History: Springdale, Arkansas, 2010.

Massey, Richard. “Madison County remains rural.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 7-26-2010.

Massey, Richard. “Mill owner rebuilding days after fire.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 12-13-2009.

Masterson, Mike. “Huntsville clinic started from zip.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 5-7-2017.

No-Ark Girl Scout Camp brochure, circa 1967. Special Collections, Mullins Library, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

Northwest Arkansas Times. “Early Alabama Visitor Killed in Accident in Madison County.” 6-14-1960.

Northwest Arkansas Times. “Pioneers Of Madison County Established Churches Early.” Undated article in Shiloh Museum research files.

Owens, J. J. “History of A Madison County Industry.” Madison County Record, 1-20-1972.

Owens, Nathan. “Hemp firm partners with UA researchers to develop cannabis.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 1-1-2019.

Ozark Natural Science Center. “Our History.” (accessed 4/2019)

Pacher, Sara. “Rural Life in Northwest Arkansas.” Mother Earth News, Sep/Oct 1986. (accessed 4/2019)

Painter, Steve. “Counties rebrand tourism effort.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 4-20-2012.

Phillips, Jared M. “Back-to-the-Land Movement.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 12-20-2016. (accessed 4/2019)

Putthoff, Flip. “Clifty landowners raise stink over Tyson sludge odor.” Rogers Morning News, 9-6-1989.

Rayburn, Otto Ernest. “Kingston Gold Mine.” Kingston Mirror, 12-7-1929. Reprinted in Madison County Record, 4-5-1990.

Rhodes, Sonny. “Tiny Ozark town a mixture of old, new.” Arkansas Democrat, 5-7-1979.

Russell, Joy, and Kevin Hatfield. “Timeline of events that shaped Madison County.” Madison County Record, 9-29-2011.

Russell, Joy. “Black History in Madison County.” Madison County Musings, Vol. XXXII, No. 1 (Spring 2013).

Russell, Joy. “Kingston, Arkansas, Part Three.” Madison County Musings, Vol. XVIII, No. 1 (Spring 1999).

Russell, Joy. “Madison County Memories.” Madison County Record, 11-30-2017.

Russell, Joy. “Madison County Memories.” Madison County Record, 4-27-2017.

Russell, Joy. “Madison County Memories.” Madison County Record, 4-13-2017.

Russell, Joy. “School integrated early.” Madison County Record, 9-29-2011.

Russell, Joy. “Split allegiances led to Massacre.” Madison County Record, 9-29-2011.

Russell, Joy. Email re: Upper Campground and present-day lumber sawmills. 4-24-2019.

Shelnutt, Matt. “Camp Noark, Girl Scout staple, likely to close.” Madison County Record, 3-10-2016.

Shelnutt, Matt. “Last 7 years will determine county’s fate for decades to come.” Madison County Record, 7-10-2014.

Shelnutt, Matt. “Willhite mill rises from the ashes.” Madison County Record, 10-7-2010.

Smith, A. T. “WWII vets learned farm training.” Madison County Record, 2-10-2005.

Snipes, Mike and Ruth Ann. “Gatherin’ at Muddy Gap,” Arkansas Democrat, 7-4-1965.

Springdale News. “Huntsville Airport: Do-It-Yourself.” 9-1-1985.

Springdale News. “Old Houses Reflect Historical Era.” 10-16-1977.

Springdale News. “Things Changing in Madison County.” 2-21-1982.

Steed, Stephen. “Poultry plant odor divides town.” Arkansas Gazette, 9-5-1989.

Sutton, Bob E. Early Days in the Ozarks, Book I of IV Books. Times-Echo Press: Eureka Springs, Arkansas, 1950.

Thompson, Henry. “Uncle Henry Thompson Writes of Old Times.” Madison County Record, 4-26-1951. Reprinted in Madison County Musings, Vol. XXXVII, No. 3 (Fall 2018).

Tibetan Cultural Institute of Arkansas. “Land of Infinite Bliss.” (accessed 4/2019)

Tolliver, Preston. “Hemp company, university to start Hindsville operation.” Madison County Record, 12-20-1918.

Tolliver, Preston. “Huntsville poised for growth, but needs help getting the ball rolling.” Madison County Record, 7-12-2018.

Tolliver, Preston. “Huntsville Schools prepping for drops in future funding.” Madison County Record, 11-2-2017.

Tolliver, Preston. “Jail housing cost county $575K in 2018.” Madison County Record, 1-10-2019.

Tolliver, Preston. “Ministerial Alliance: Finding help through fellowship.” Madison County Record, 6-24-2016.

Turnbo, Silas Claiborne. “A Way Back in the Early Days of Madison County, Ark.” Turnbo Manuscripts by Silas Claiborne Turnbo, 1844-1925, Springfield-Greene County Library. (accessed 4/2019)

Wahlquist, W. H. “Some Sixty-Year Old History of Huntsville and Vicinity,” Madison County Record, 12-24-1936. Reprinted in Madison County Musings, undated.

Walden, Kate Hudson, Dixie Hudson Roberts, and L. N. Hudson. “History of Marble, Madison County, Arkansas.” Madison County Musings, Vol. XIII, No. 3 (Fall 1994).

Walkenhorst, Emily. “Migration fuels state’s growth.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 4-18-2019.

White, Ray. “N.Y.A. Camp Swinging Into Peak of Working Power.” Madison County Record, 2-9-1939.

Wilson, Dorothy Ware. Rial Williams’ Thirty-One Children. ARC Press of Cane Hill: Cane Hill, Arkansas, 1995.

Wood, Mary. “Ozark-St. Francis National Forests.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 3-6-2014. (accessed 4/2019)

Zajicek, Anna, and Allyn Lord. “Yellowhammer.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, 11-2-2017. (accessed 4/2019)

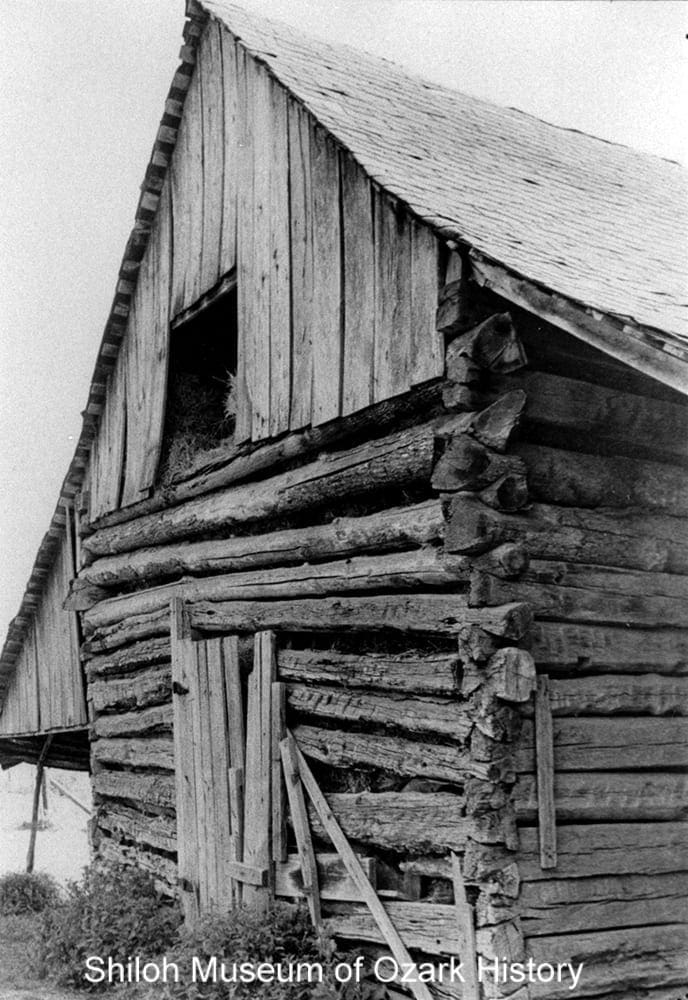

Single Pen—One pen with a front door and an exterior chimney on one end.

Single Pen—One pen with a front door and an exterior chimney on one end. Double Pen—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the two pens, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Double Pen—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the two pens, and two exterior chimneys on either end. Saddlebag—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the pens, and a central interior chimney.

Saddlebag—Two pens, side-by-side, with two front doors, an interior doorway connecting the pens, and a central interior chimney. Dogtrot—Two pens connected by a covered, central breezeway, with two or more doors on the front of the house and in the breezeway, and two exterior chimneys on either end.

Dogtrot—Two pens connected by a covered, central breezeway, with two or more doors on the front of the house and in the breezeway, and two exterior chimneys on either end.