Prized Possessions

PRIZED POSSESSIONS

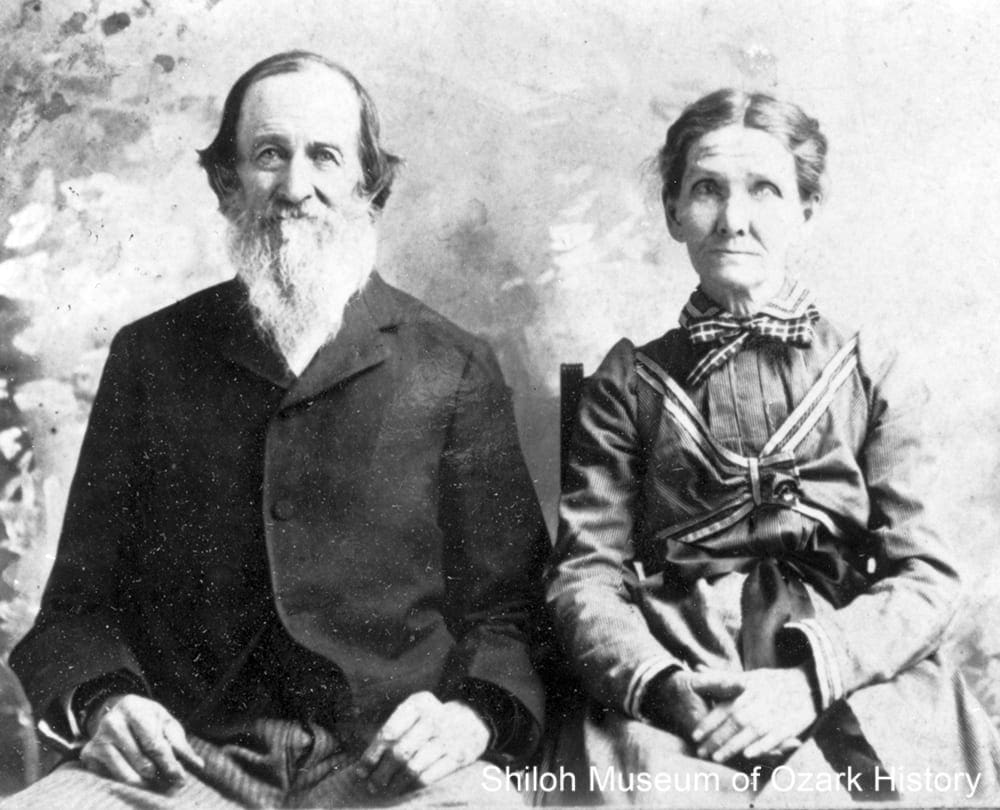

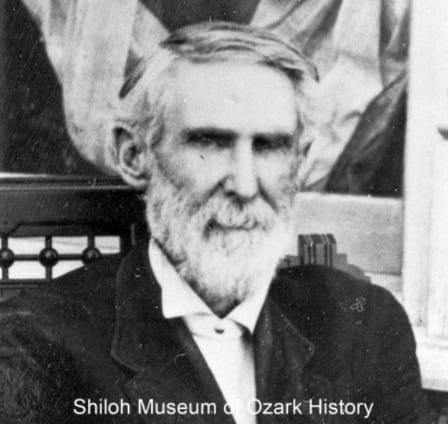

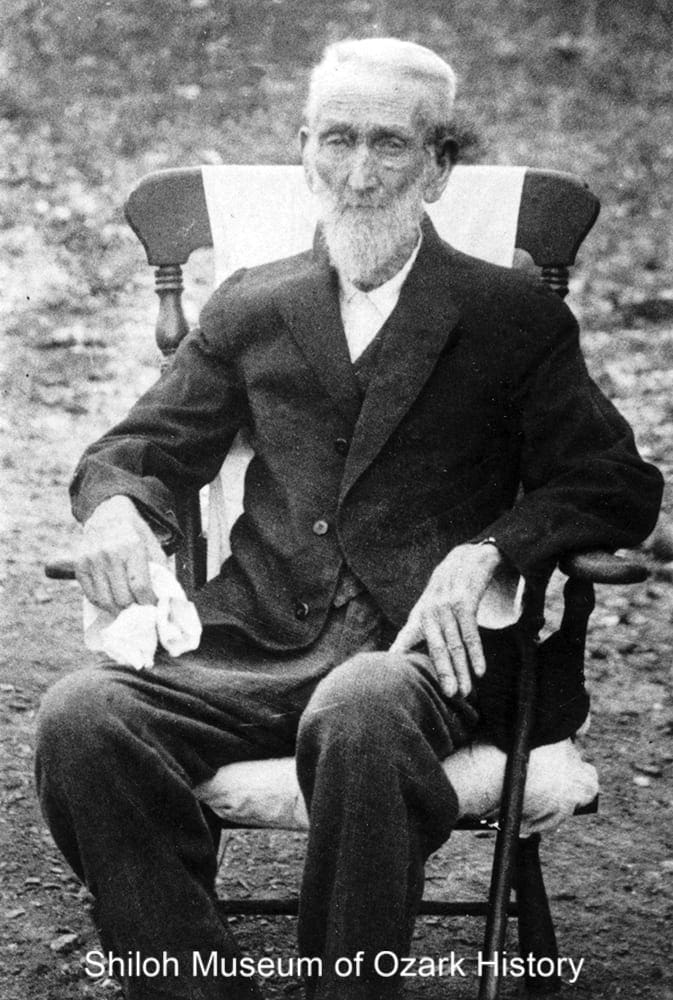

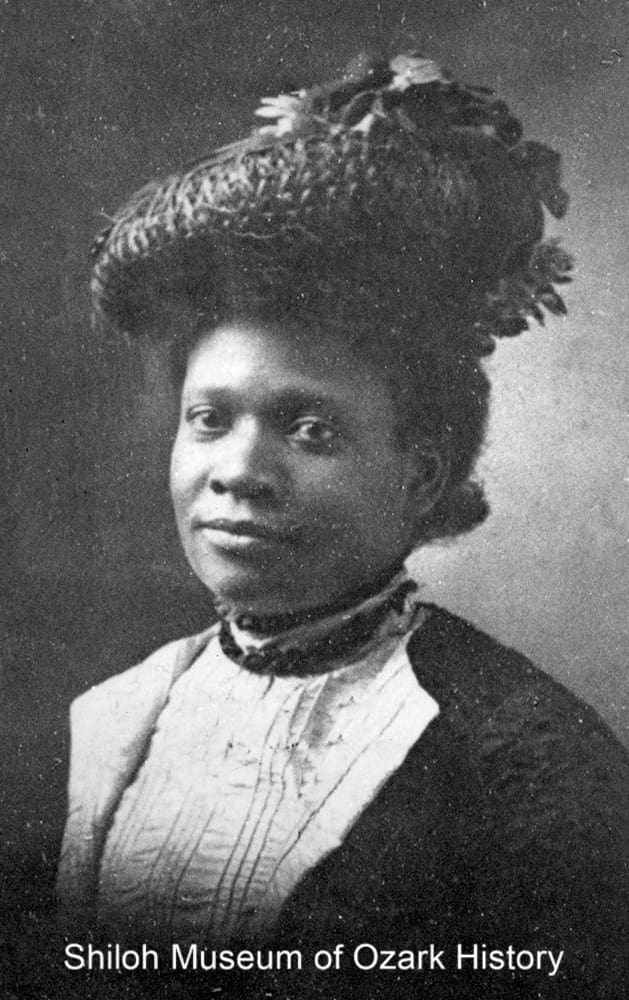

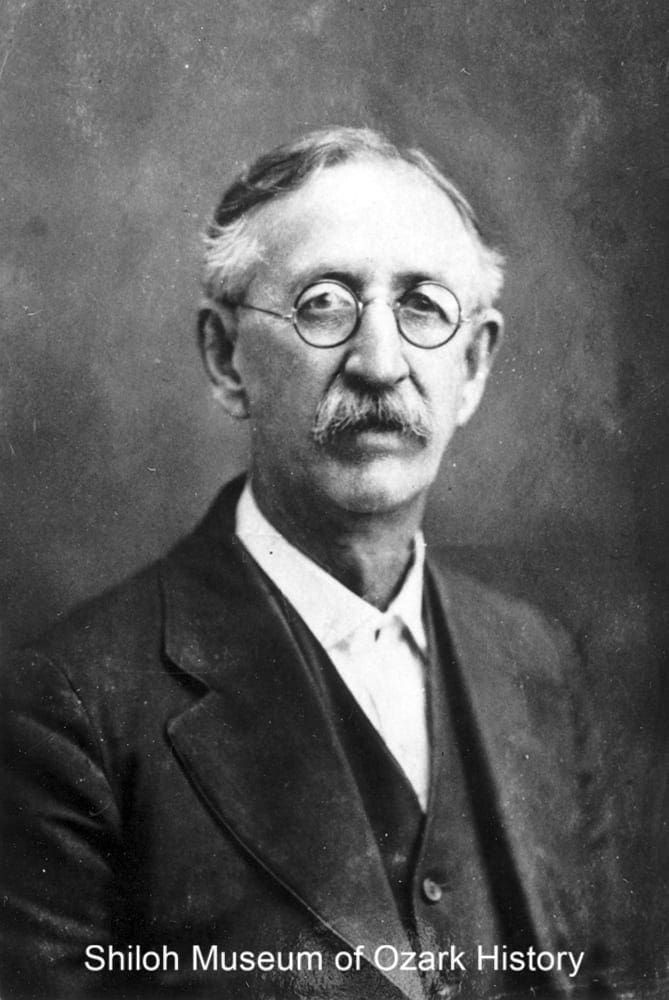

Online ExhibitWhen we sit for a formal portrait we carefully consider what we wear, where we stand, and what we pose with. Our picture is composed to tell a story, to record a moment in our lives.

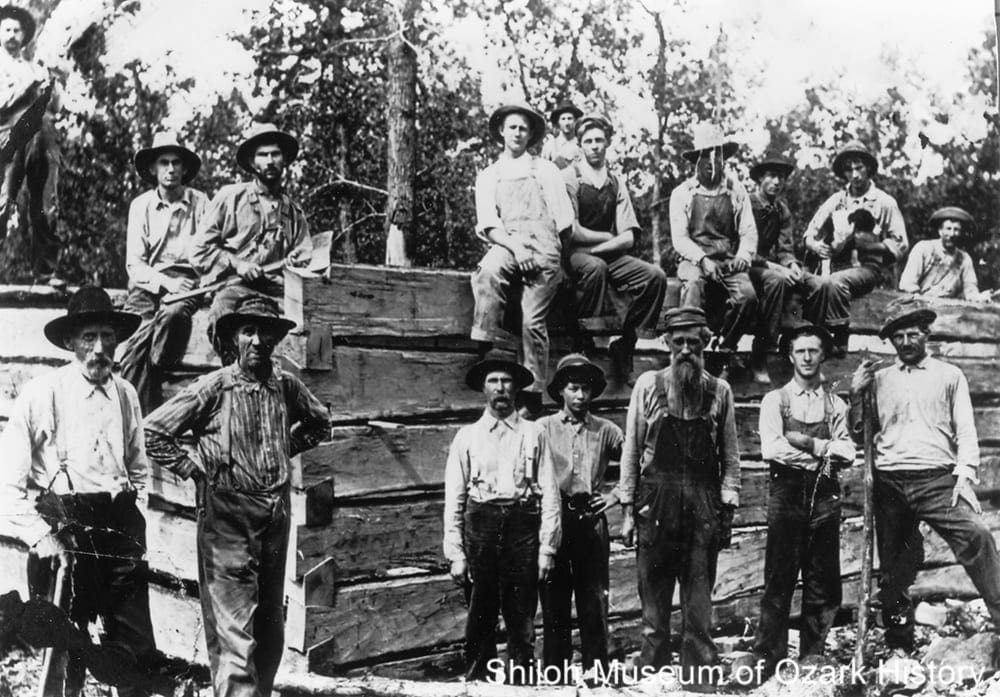

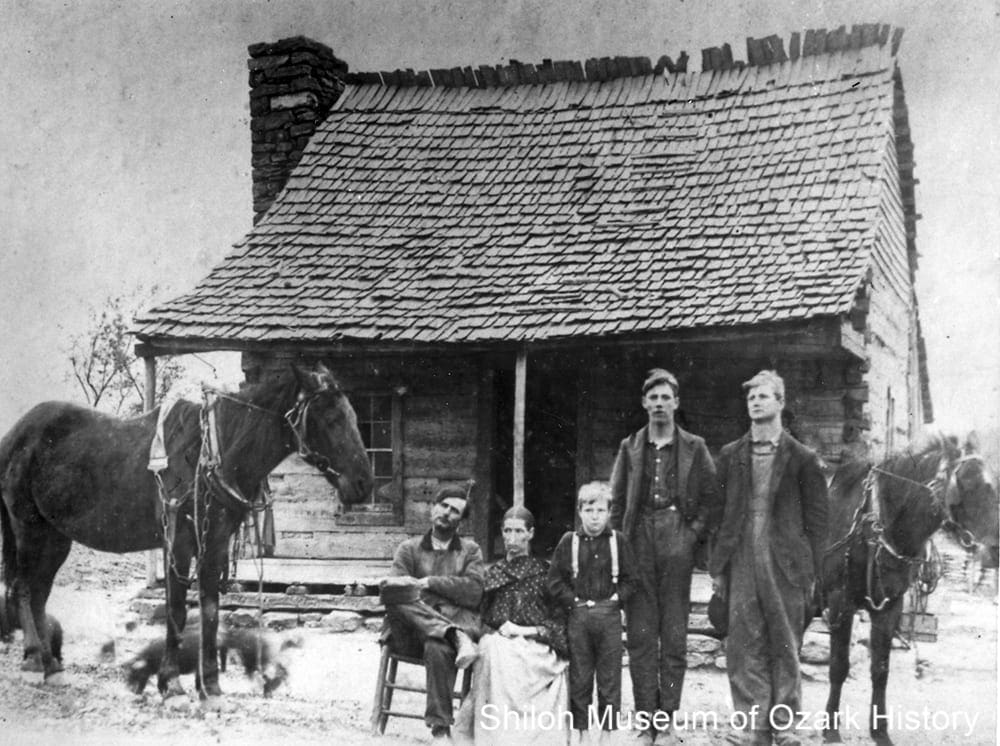

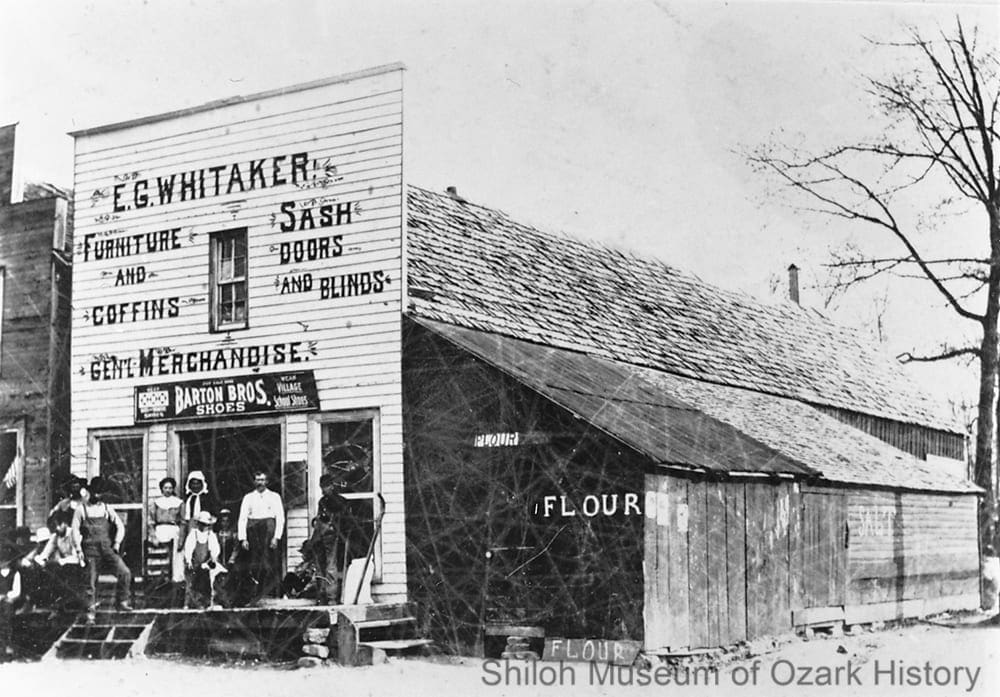

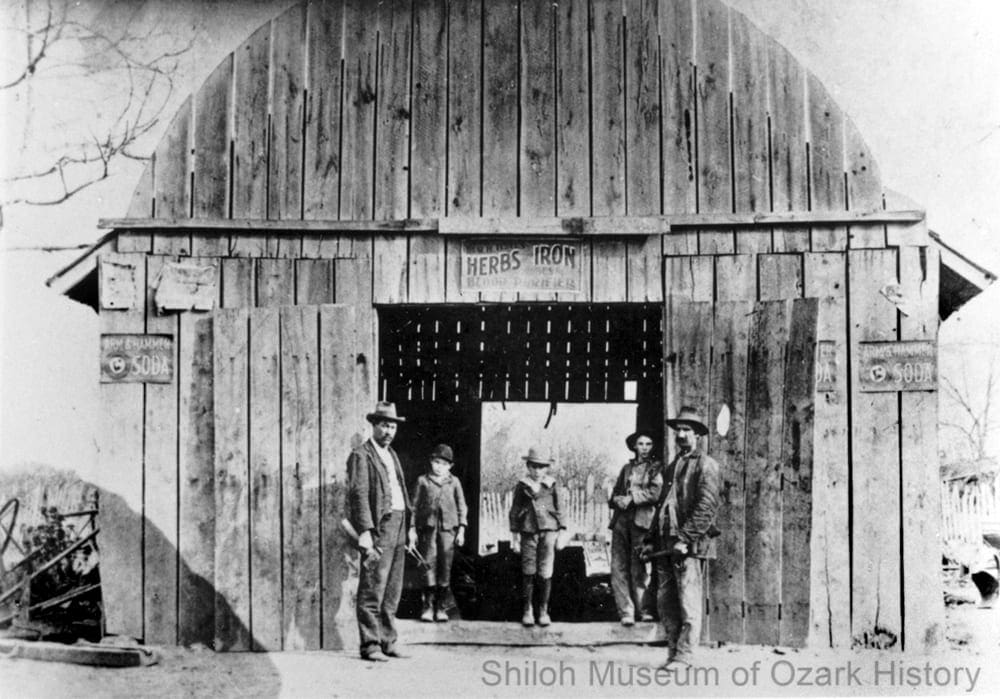

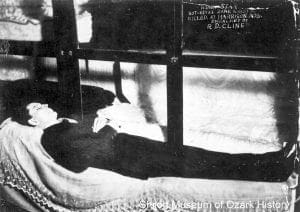

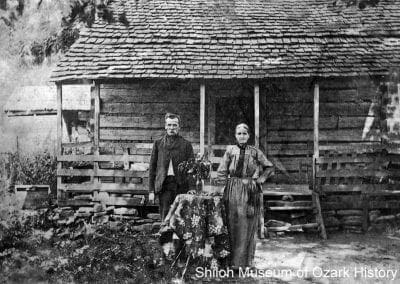

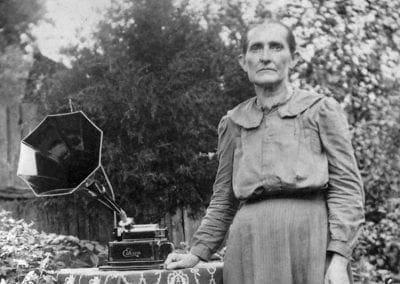

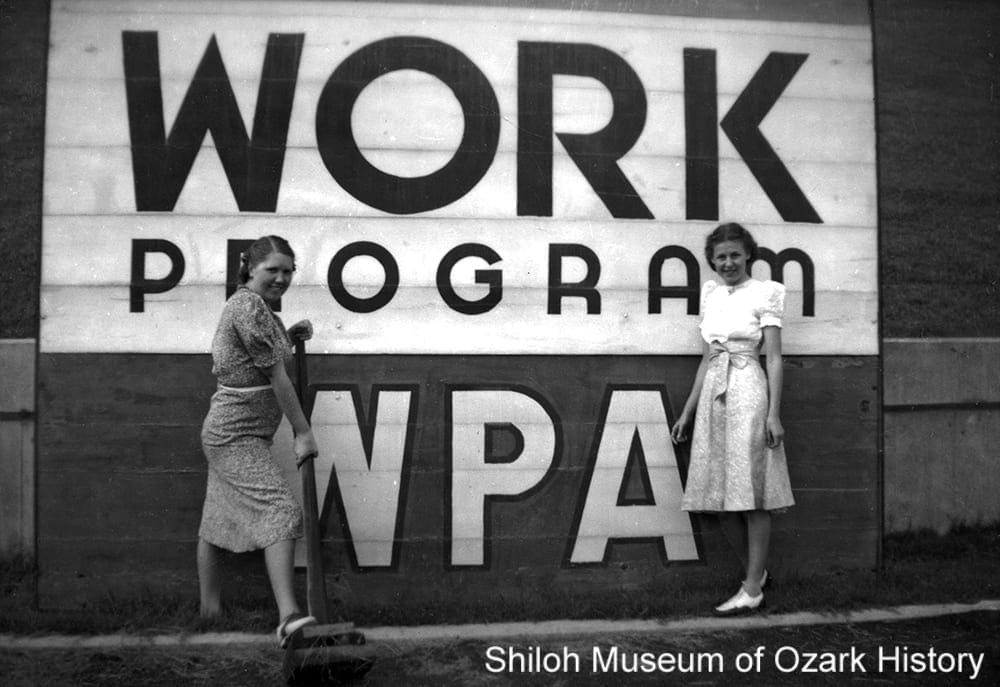

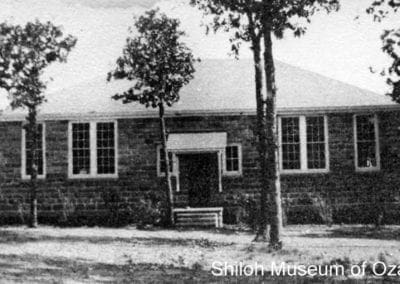

What we pose with says a lot about us. If we pose in front of our house with our horses and household goods we show our prosperity. Posing with a pretty quilt or a spinning wheel shows our talent, while posing with a Bible shows our faith. Including a framed photo of a departed loved one in a photo shows that they are still part of our lives.

In the past it was usually only the rich and powerful who had their portraits painted by artists. Once the camera was invented in the early 1800s many people could afford portraits. Traveling photographers often took pictures of folks outside their homes.

Back then low lighting and camera technology made it difficult to take photos indoors, so folks brought their treasured items outside. A favorite doll, a pack of hunting dogs, a piece of fancy furniture. Wearing their best clothing, a family posed with their prized possessions in front of their home, another source of pride. The photo could then be sent to family and friends to let them know that all was well.

Today we still pose for photos with our favorite things, although we might use our cell phone to take the shot and send it instantly around the world.

When we sit for a formal portrait we carefully consider what we wear, where we stand, and what we pose with. Our picture is composed to tell a story, to record a moment in our lives.

What we pose with says a lot about us. If we pose in front of our house with our horses and household goods we show our prosperity. Posing with a pretty quilt or a spinning wheel shows our talent, while posing with a Bible shows our faith. Including a framed photo of a departed loved one in a photo shows that they are still part of our lives.

In the past it was usually only the rich and powerful who had their portraits painted by artists. Once the camera was invented in the early 1800s many people could afford portraits. Traveling photographers often took pictures of folks outside their homes.

Back then low lighting and camera technology made it difficult to take photos indoors, so folks brought their treasured items outside. A favorite doll, a pack of hunting dogs, a piece of fancy furniture. Wearing their best clothing, a family posed with their prized possessions in front of their home, another source of pride. The photo could then be sent to family and friends to let them know that all was well.

Today we still pose for photos with our favorite things, although we might use our cell phone to take the shot and send it instantly around the world.

Photo Gallery

89-94-17

The William Ross Little family with their horses and tricycle, Summers (Washington County), early 1900s. Mary Ellen Johnson Collection (S-89-94-17)

2006-27-7

Noted horseman Carl Ownbey Sr. with his matched pair of horses, Spring Street, Springdale, early 1900s. Carl Ownbey Collection (S-2006-17-7)

84-2-12

The Alex Stockburger family with their Bible, Greenland area, (Washington County), 1910s. Robert G. Winn Collection (S-84-2-12)

89-40-12

Susan Wolfe Hubbard with her dogs, Washington County, 1916. Ruth Morris Collection (S-89-40-12)

84-50-40

James and Cynthia Secor with their quilt, LaRue (Benton County), 1920s. Doris Leak Collection (S-84-50-40)

P-2457

Ewing A. Webb and his grandson Bobby Earl Stewart with their Webb family heirlooms, Fayetteville, 1941. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2457)

2000-1-10

The Hernando A. G. Smith family with their farm wagon, Huntsville area, 1890s. Virginia Threet Collection (S-2000-1-10)

89-12-38

Unidentified woman with her cat, Grandview area (Carroll County), 1890s-1900s. Dr. Alonzo Evering Quinn, photographer. June Crane Collection (S-89-12-38)

2006-14-52

The Robert B. Reed family with their horses and wagons, Benton County, circa 1910. Daline Reed Smith Collection (S-2006-14-52)

P-1971

Lavinia Lewis Ramey and her grandson Rayman A. Reed with their horses, “Old Charley” and “Old Boston,” Washington County, circa 1910. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-1971)

2003-65-2

William Garland Ownbey and his son Julian with the family’s first automobile, Springdale, 1909. Springdale News Collection (S-2003-65-2

85-111-104

The Curtis residence with Bob Curtis and Andy Karnes and their hunting dogs, West Fork, 1900s. Washington County Observer Collection (S-85-111-104)

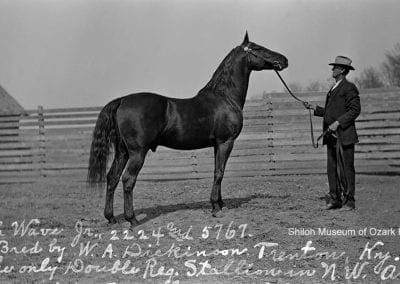

97-57-321

William Farish with his double-registered stallion, “High Wave,” Johnson, early 1900s. Marion Mason, photographer. Maudine Sanders Collection (S-97-57-321)

99-40-10

The James L. Auslam family with their horse, “Daisy,” and dolls, Huntsville, 1904. Jim Auslam Collection (S-99-40-10)

98-85-817

Ada Lee Smith Shook with her favorite toy, “Clowny,” Fayetteville, 1929. Ada Lee Shook Collection (S-98-85-817)

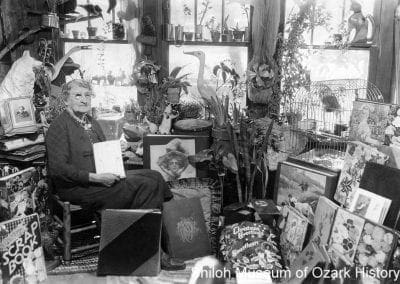

89-114-99

Maggie Glover Morgan with her scrapbooks, other mementoes, and her parrot, “Pollie,” Springdale, 1930s. Sue K. McByrde Collection (S-89-114-99)

P-398

The George N. Barton family with their special mementoes framed in the doorway, Fayetteville, early 1900s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-398)

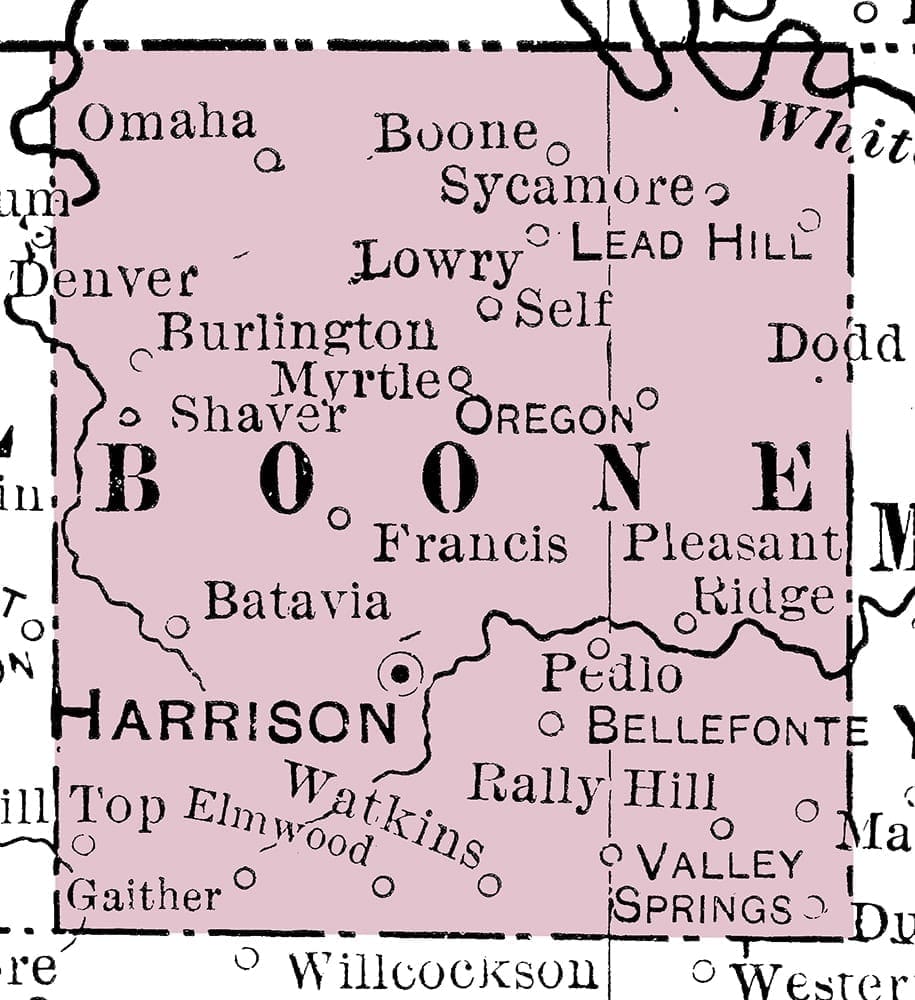

91-6-41

The Clarence Collins family with their horses and framed portrait of their deceased son, Alvie, Boone County, circa 1908. Lonnie Walker Collection (S-91-6-41)

P-4741

Martha Young with her book, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Fayetteville, early 1900s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4741)

99-32-312

Lucinda Muncie Ogden with her family Bible, Madison County, circa 1910. Earl L. Ogden Collection (S-99-32-312)

90-194-159

J. Fay Reed in his surrey, Fayetteville, about 1900. Peter Harkins Collection (S-90-194-159)

92-110-174

The Joseph M. Smith family with their spinning wheel, hunting dog and rifle, and horse, southeast Washington County, early 1900s. (S-92-110-174)

P-4662

Unidentified girl with her tricycle and doll, Fayetteville, early 1900s. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-4662)

99-1-146

Robert and Parmilla Sullins with their draped table and vase of flowers, Japton (Madison County), early 1900s. Jim Rogers Collection (S-99-1-146)

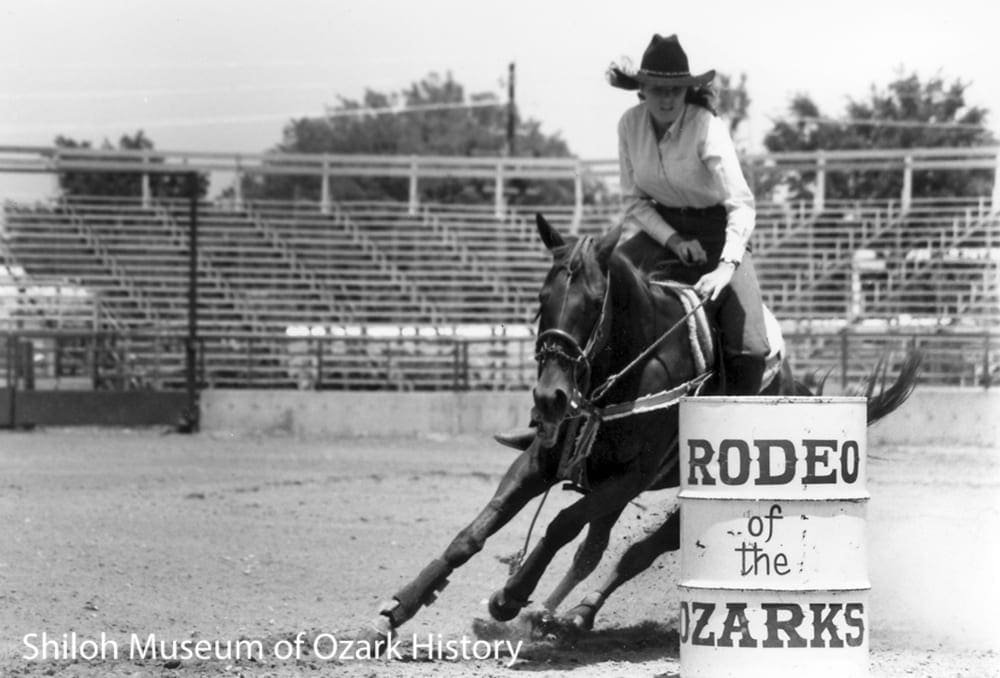

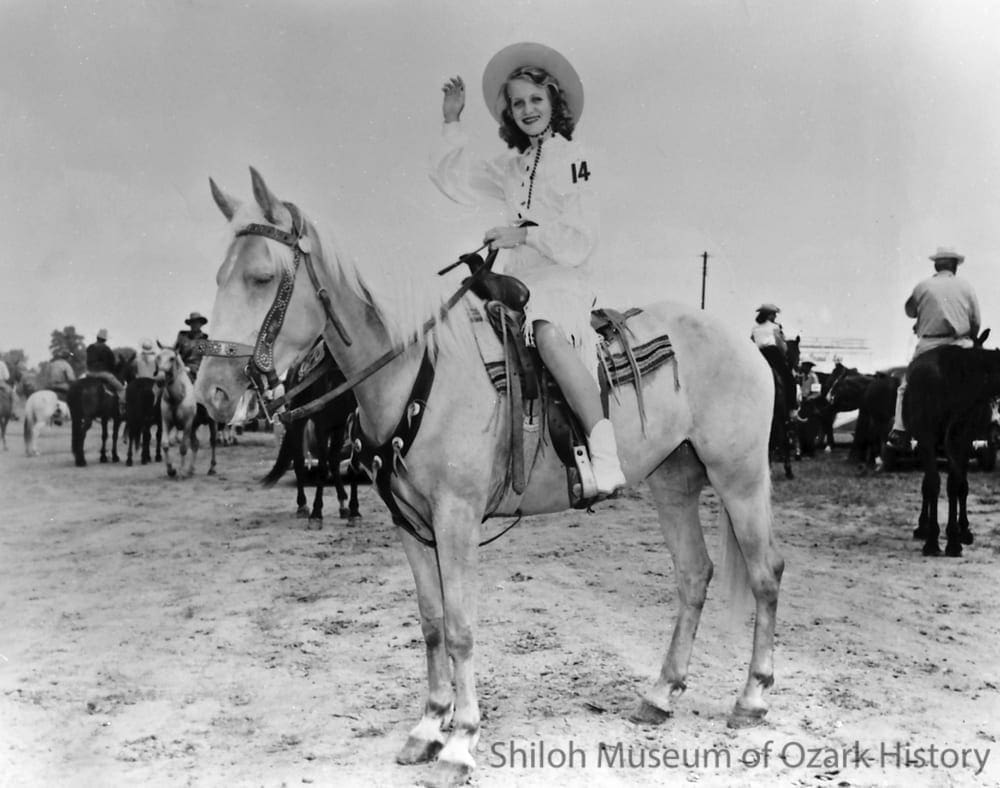

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.