Spout Spring—A Place Where People Live

The Manuel family Victory Garden on East Center Street, Fayetteville, May 1943. From left: Chris Manuel, Bayley Joiner (block chairman of the food-for-victory drive), and Lola Young Manuel. Northwest Arkansas Times, photographer. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2437)

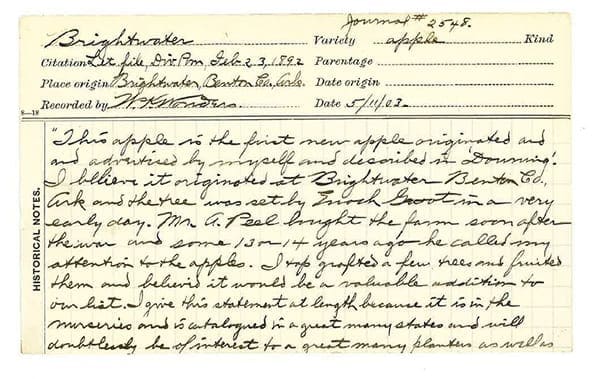

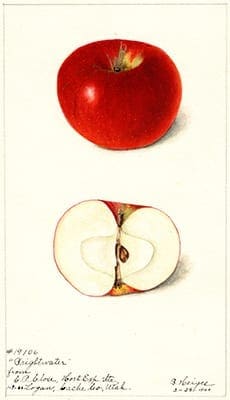

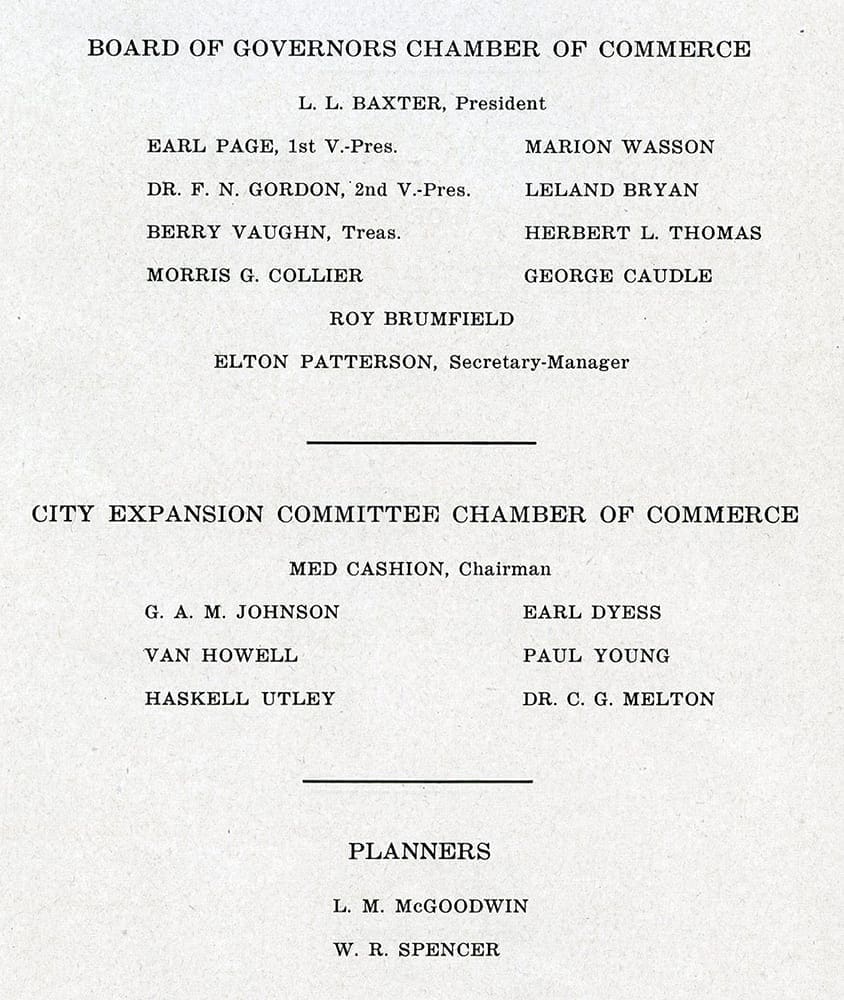

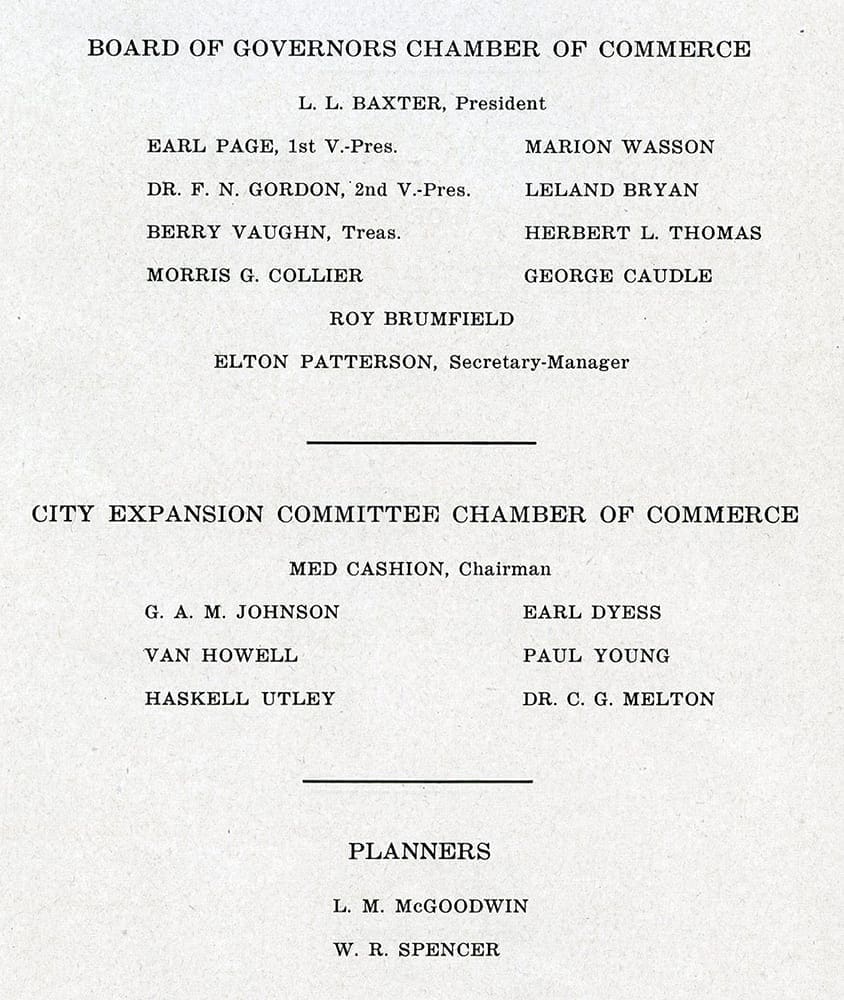

Hopeful that the end of World War II was on the horizon, in January 1945 the Fayetteville Chamber of Commerce hired two engineers to envision the “Fayetteville of Tomorrow” by positioning the town “to receive the most benefit from post-war construction programs.” Working with input from the Chamber, city government, citizen groups, church leaders, and others, the resulting document—Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan—was published that fall. Key components were the development of a civic center west of the town square, a hospital expansion, the rerouting of a major highway, and the improvement or development of through-roads, parks, schools, and utilities.

|

Authors and contributors to the Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74) |

|

Authors and contributors to the Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74) |

I came across the plan while reviewing a large donation of photographic and archival materials from Ann Wiggans Sugg. Curious, I began reading and was soon struck by how easily the plan’s proponents recommended the destruction of a long-standing, close-knit neighborhood, a neighborhood whose residents likely had no say in the matter. Despite the plan’s carefully couched reasons as to why everyone would benefit, the neighborhood’s removal would further marginalize an already marginalized population.

The report’s authors dubbed Fayetteville “A City of Homes, A Place Where People Live.” Back then the town’s boundaries stretched roughly from the veteran’s hospital in the north, to the western edge of Mount Sequoyah in the east, to U.S. Highway 62 in the south, and to North Garland Avenue on the west. With over 8,200 citizens, its economy relied largely on agricultural products (fresh and processed), the University of Arkansas, and forestry products (lumber and veneer). It was expected that population, land area, retail and trade, industry, and tourism would continue to grow.

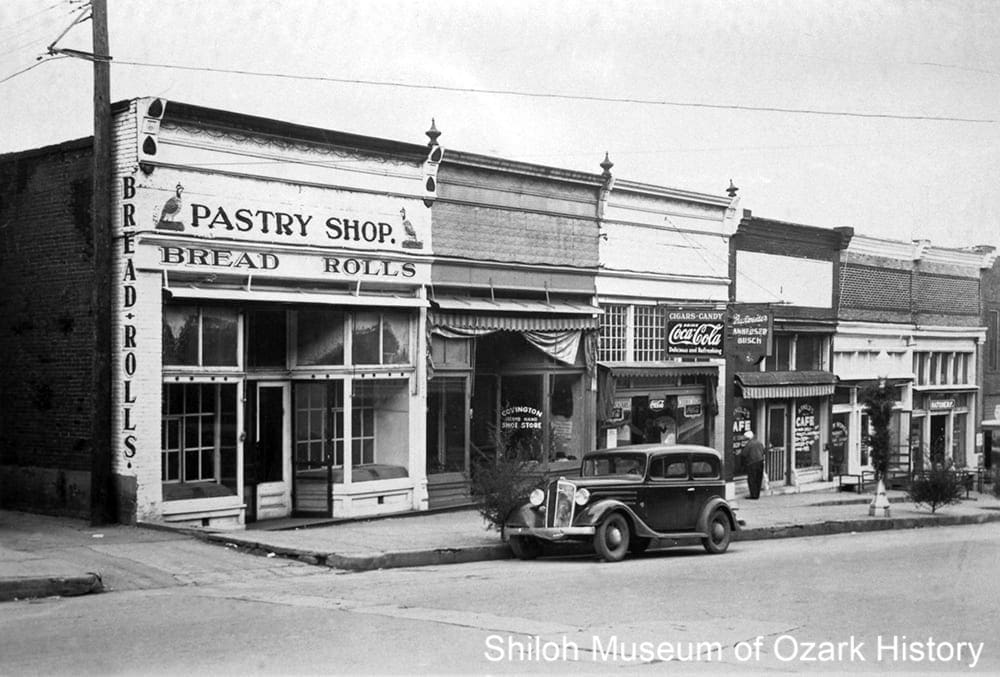

Highway 71 (College Avenue) in front of the Washington County Courthouse, about 1940. Mr. and Mrs. Sherman Hinds Collection (S-87-63-8)

Transportation needs were a concern. As a major thoroughfare, U.S. Highway 71’s narrow lanes and steep grades posed a problem for commercial trucks traveling through town. The road also cut through the business district, limiting growth and burdening in-city traffic. The solution? Reroute it to the east through Spout Spring.

Spout Spring was a neighborhood settled by formerly enslaved people and their descendants sometime after the Civil War. Encompassing a small valley with a spring-fed creek just east of what was then the Washington County Courthouse, the community core included East Meadow, Center, Mountain, and Rock Streets along with South Willow and Washington Avenues.(1) Its cornerstone institutions were the Mission School for Negroes Only (1866, renamed Henderson School in the 1890s), St. James Methodist Episcopal Church (1868), St. James Baptist Church (1885), and Lincoln Elementary School (1936), which replaced Henderson as the neighborhood school.

Susan Marshbank Manuel at her home on North Olive Avenue, Fayetteville, 1940s–early 1950s. “Mama Susie,” as she was known, offered accommodations for African-American travelers. Her home was listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book from 1939-1956.(2) Betty Hayes Davis Collection (S-2015-71-12)

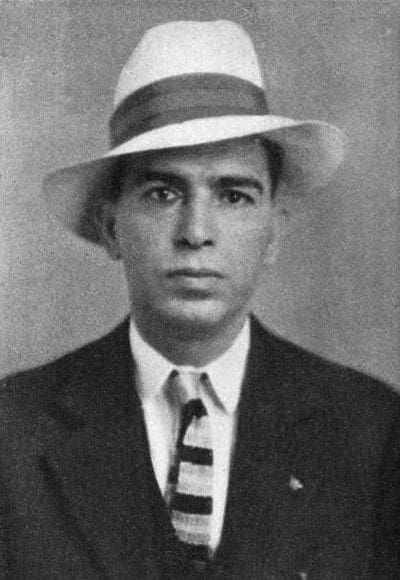

One of the first formerly enslaved African-Americans to purchase land near the core of Spout Springs was Tabitha Marshbank Taylor. In 1879 she bought a large lot on North Olive Avenue (3), which provided space for her and her descendants to build homes.(4) More folks bought property in the valley as early as the 1890s.(5) Many of Spout Spring’s residents worked as housekeepers, laborers, railroad porters, cooks, dishwashers, and shoe-shiners, in large part the only jobs that were open to them. Some operated small businesses out of their homes such as cafés, barbershops, and juke joints. Extra income was earned by renting rooms to travelling workers and, once it was integrated in 1948, University of Arkansas students. Because Fayetteville’s high school was for whites only, Black students seeking higher education were forced to move to larger Arkansas cities like Fort Smith and Pine Bluff or elsewhere to earn their diplomas.

High School graduate Betty Hayes with her mother Clara Manuel Hayes in the yard of their home on North Olive Avenue, 1945. Betty lived in St. Louis with her uncle while attending Sumner High School. Also seen is the home of Tabitha Marshbank Taylor, Betty’s great grandmother, who bought the property in 1879. Betty Hayes Davis Collection (S-2015-71-50)

Spout Spring is identified as “Tin Cup” in the plan. According to Jessie B. Bryant, civic leader and founder of Northwest Arkansas Free Health and Dental Center, the name was used by white businessmen who stopped by the area for a cup of cool spring water and a quick bite of lunch. In a 2000 article in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette she said, “That’s the misconception of it all. It wasn’t part of the Black neighborhood. . . . if you mention ‘Tin Cup’ it’s automatically a derogatory term for the people in the community. But it had nothing to do with the community.”(6) University of Arkansas professor Dr. Gordon Morgan and his wife Dr. Izola Preston Morgan said much the same in a 1975 Northwest Arkansas Times article. “The Black community has never really considered itself as having a separate identity from that of Fayetteville at large. It has resisted such names as the Can, the Hollow, Tin Cup, and even East Fayetteville. These names have been given it by outsiders . . . who have had no practical knowledge of [the] history of the community.”(7)

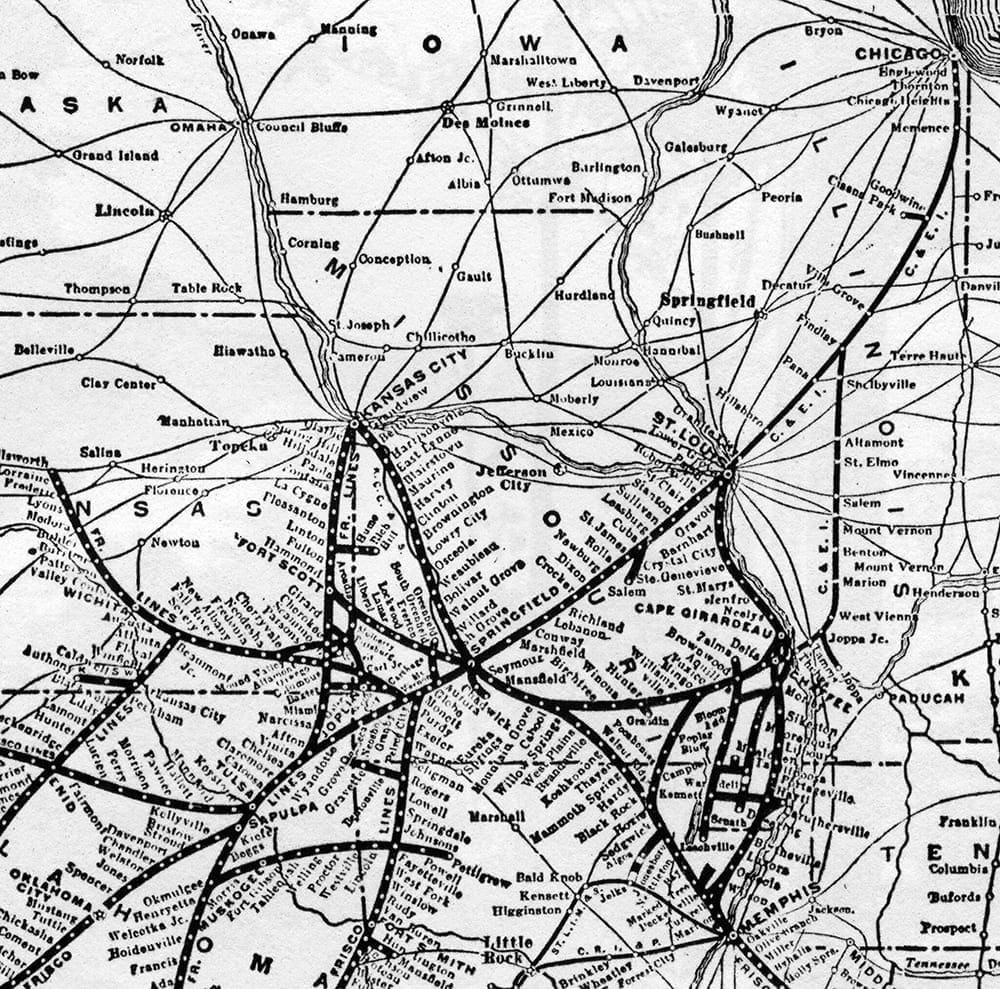

| Plate No. V depicts the proposed route change of U.S. Highway 71 through Fayetteville. A star has been added to mark the location of the Washington County Courthouse. | |

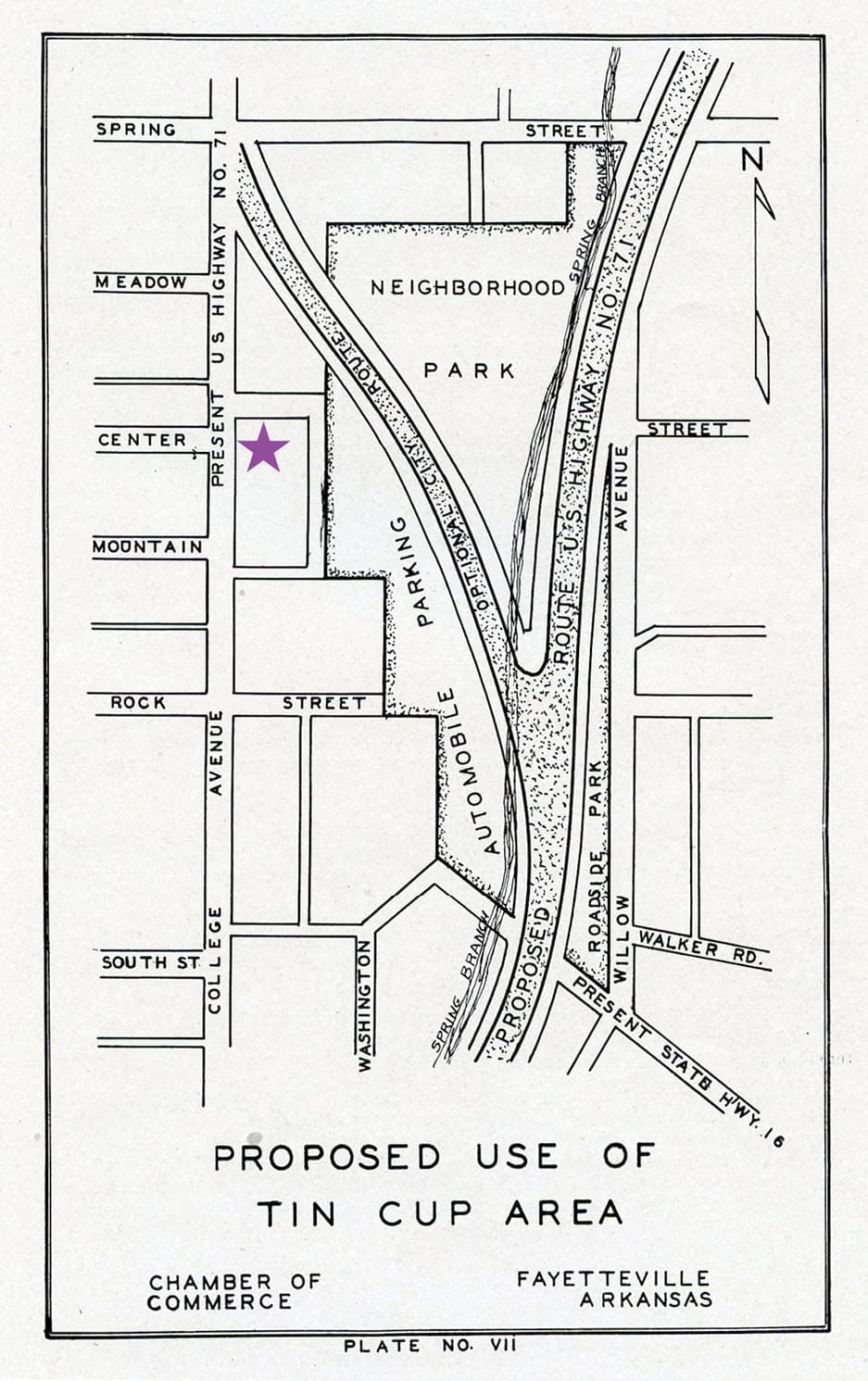

| Plate No. VII depicts a closeup of the route through the Spout Spring neighborhood, with proposed recreational parks and parking lot. A star has been added to mark the location of the Washington County Courthouse. |

The plan labeled Spout Spring as having sub-standard housing and deemed it a poor use of land. Because the area was considered a “natural beauty spot which should be preserved” and as “an area that will do much toward selling Fayetteville to the traveling public,” planners proposed rerouting Highway 71 east through Spout Spring. The adjacent land would be used to create two recreational parks and a parking lot for the use of citizens and travelers.

The suggestion was made to move the valley’s African-American residents to a federally funded, segregated “Negro Housing Project” just beyond the southeastern edge of town, in the belief that “when two races are mixed in a neighborhood all property loses value.” An adjacent ten-acre park centering on Wood Avenue would be developed “to serve the Negro population for recreation, school and church facilities.” Moving the city’s Black residents away from downtown meant that their new neighborhood would be “separate from areas of thickly settled white population” while being “close enough to the Business Section of the city as practical.” In other words, close enough for Blacks to continue to work for whites, but not so close as to impact their neighborhoods.

Government-sanctioned segregation was hardly a new idea. During the Great Depression of the 1930s the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure home mortgages in or near existing Black communities, considering the risk of falling property values too great. In urban areas, African Americans were pushed towards segregated housing projects which were often cut off from the rest of the city by major roads and highways.

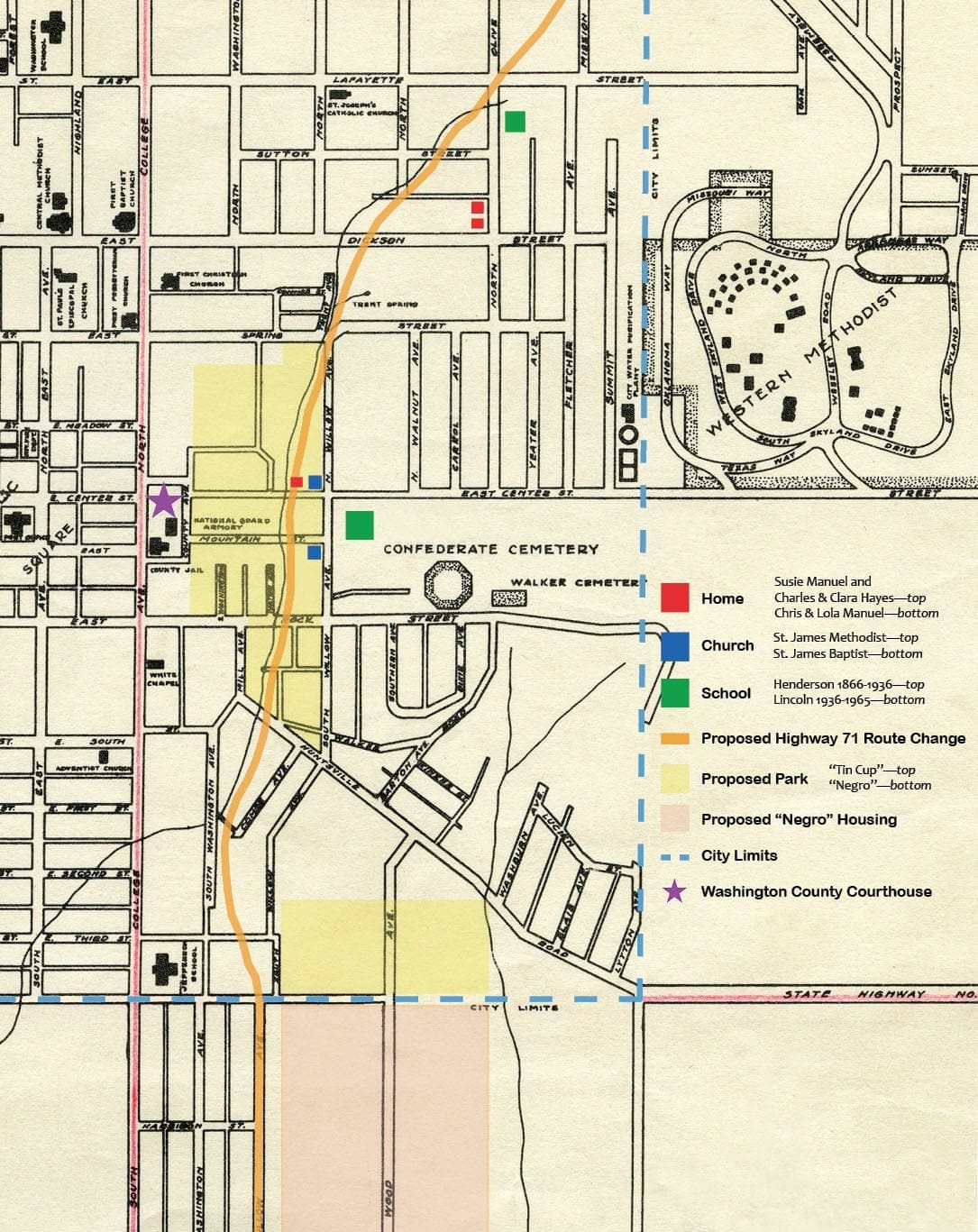

| This map depicts the locations of Spout Spring’s cornerstone institutions and the homes of some of the people pictured in this blog, contrasted against the proposed changes to the Spout Spring neighborhood and its relocation. A base map was drawn in 1936 by Fayetteville city engineer W. Carl Smith, which in turn was used as the base map for the various illustrations found in Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Neither map is to scale. |

The authors seemed confident that the “Federal Government [would] undoubtedly furnish all or part of the money for many of these projects.” Following the plan’s publication Fayetteville moved ahead with several projects, largely using city funds with some federal money for planning. Land was purchased and plans were made to expand the hospital. A new water-pumping station was built and improvements made to water distribution lines and the sewer system. In need of housing for returning World War II veterans, land adjoining City Park (now known as Wilson Park) was secured for a short-term trailer village, and later used to expand the park.

But the rerouting of Highway 71 through Spout Spring never happened. A new proposal had emerged by 1947 to build an overhead viaduct between Rock and Third Streets to overcome the steep hill south of the courthouse. Mayor George T. Sanders believed it could be done “at much less expense than condemning and buying property elsewhere.”(8) Alternate routes were later proposed but ultimately the city couldn’t secure the funds to purchase the needed right-of-way.

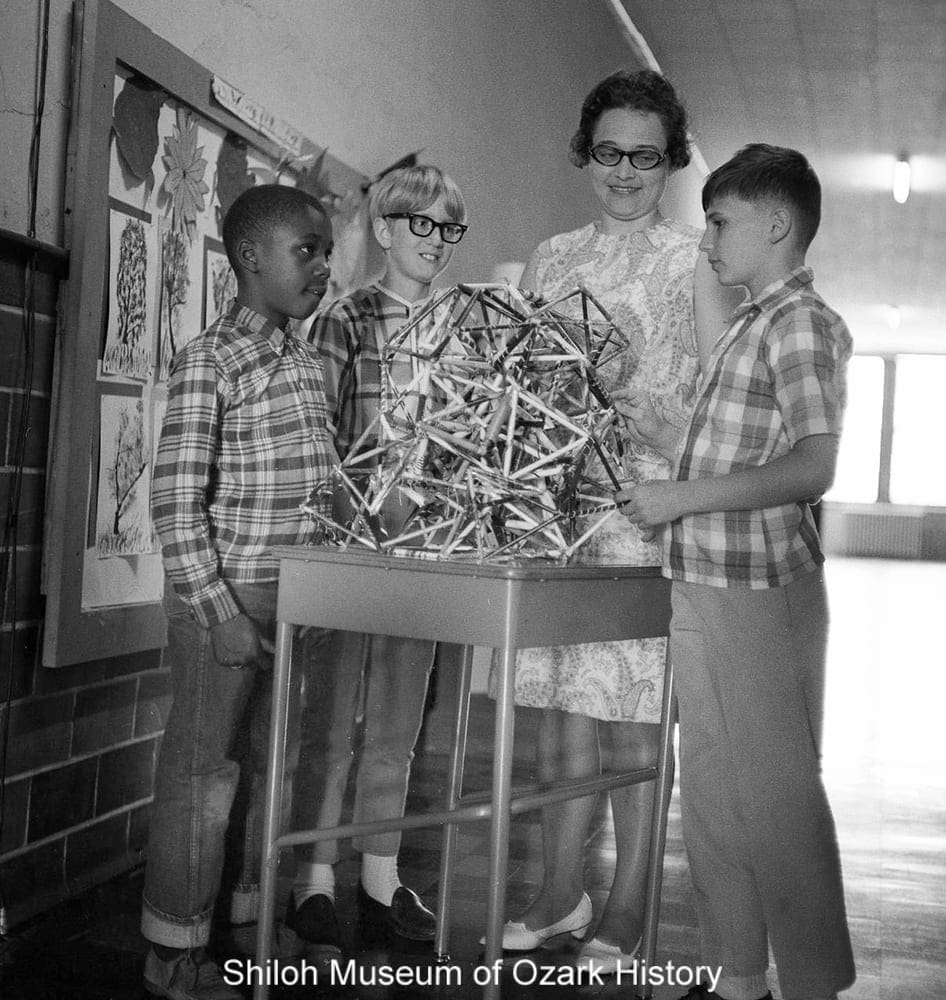

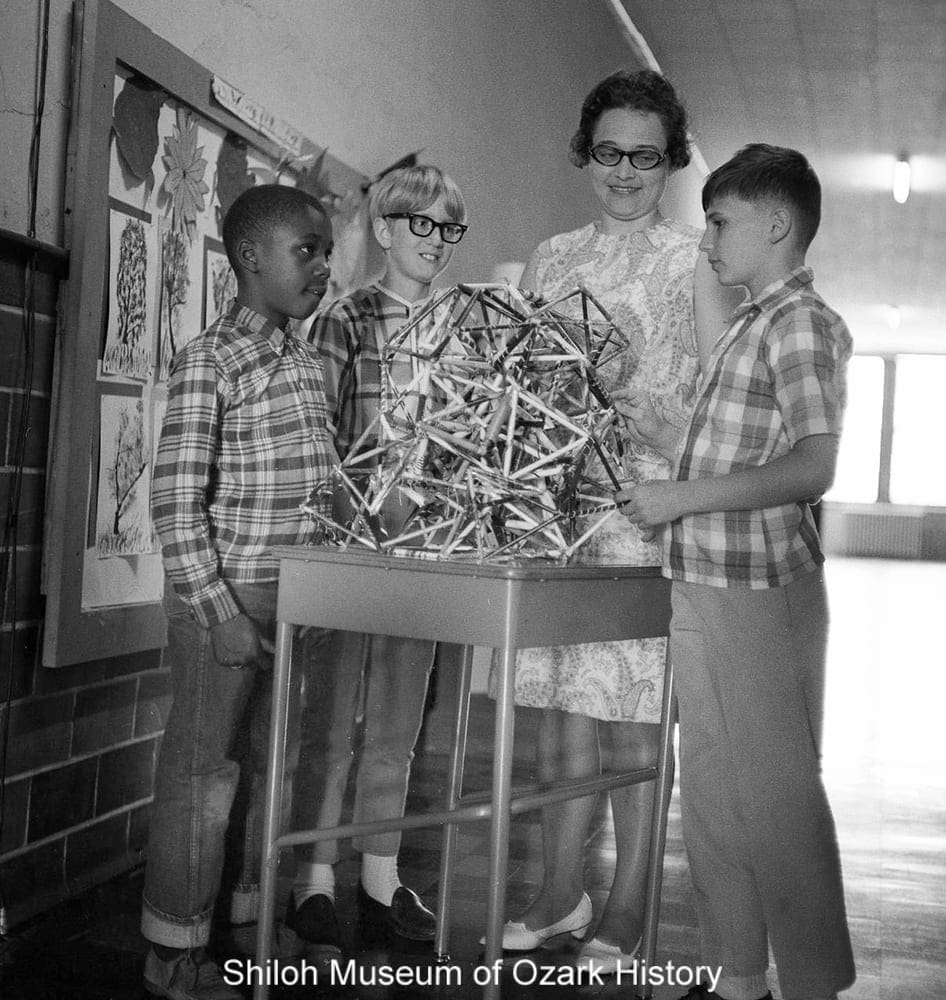

Students with their teacher at Washington Elementary School, 1966-1967. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 15 66.413)

Spout Springs continued to be “a place where people live.” While the neighborhood remained largely segregated for several more decades, its people did not. Within days of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Fayetteville’s School Board unanimously voted to integrate its high school. They considered several factors—compliance with the ruling, a concerted push by Black and white community members, and the financial burden of paying for African-American high-school students to be educated elsewhere.(9) That fall seven Black students were welcomed in what was said to be a smooth, orderly fashion. Not that there weren’t difficulties throughout the year, but they were nothing like what befell the students who attempted to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. While Fayetteville’s junior high was integrated in 1955 it took another ten years before the school board integrated the elementary schools. In response to community petitions, the city’s movie theaters and the Wilson Park swimming pool were opened to Blacks in 1963. The following year Melvin E. Dowell was the first alumnus of Lincoln Elementary and Fayetteville High to receive a degree from the University of Arkansas.

FOOTNOTES

1. Information gleaned from the 1940 U.S. Census, based on race, house number, and street name.

2. Edmark, David. “Fayetteville in the Green Book: ‘A Knit Community.’” Flashback, Fall 2019.

3. Email from Tony Wappel, 10-5-2018.

4. Interviews with Betty Hayes Davis, 2012-2016.

5. Johnson, Eric. “Spout Spring in Memory and History.” Flashback, Spring 2017.

6. Schulte, Bret. “Jessie Ballie Carr Bryant: Helping the human race.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 11-12-2000.

7. Morgan, Gordon and Izola Preston Morgan. “History Of Black Community Woven With City’s.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 7-16-1978.

8. Northwest Arkansas Times. “Rerouting of Highway 71 Up South College With Construction of Viaduct Proposed.” 4-15-1947.

9. Adams, Julianne Lewis and Thomas A. DeBlack. Civil Obedience: An Oral History of School Desegregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1954–1965. University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville: 1994.

Marie Demeroukas is the Shiloh Museum’s photo archivist/research librarian.

The Manuel family Victory Garden on East Center Street, Fayetteville, May 1943. From left: Chris Manuel, Bayley Joiner (block chairman of the food-for-victory drive), and Lola Young Manuel. Northwest Arkansas Times, photographer. Washington County Historical Society Collection (P-2437)

Hopeful that the end of World War II was on the horizon, in January 1945 the Fayetteville Chamber of Commerce hired two engineers to envision the “Fayetteville of Tomorrow” by positioning the town “to receive the most benefit from post-war construction programs.” Working with input from the Chamber, city government, citizen groups, church leaders, and others, the resulting document—Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan—was published that fall. Key components were the development of a civic center west of the town square, a hospital expansion, the rerouting of a major highway, and the improvement or development of through-roads, parks, schools, and utilities.

Authors and contributors to the Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74)

Authors and contributors to the Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74)

I came across the plan while reviewing a large donation of photographic and archival materials from Ann Wiggans Sugg. Curious, I began reading and was soon struck by how easily the plan’s proponents recommended the destruction of a long-standing, close-knit neighborhood, a neighborhood whose residents likely had no say in the matter. Despite the plan’s carefully couched reasons as to why everyone would benefit, the neighborhood’s removal would further marginalize an already marginalized population.

The report’s authors dubbed Fayetteville “A City of Homes, A Place Where People Live.” Back then the town’s boundaries stretched roughly from the veteran’s hospital in the north, to the western edge of Mount Sequoyah in the east, to U.S. Highway 62 in the south, and to North Garland Avenue on the west. With over 8,200 citizens, its economy relied largely on agricultural products (fresh and processed), the University of Arkansas, and forestry products (lumber and veneer). It was expected that population, land area, retail and trade, industry, and tourism would continue to grow.

Highway 71 (College Avenue) in front of the Washington County Courthouse, about 1940. Mr. and Mrs. Sherman Hinds Collection (S-87-63-8)

Transportation needs were a concern. As a major thoroughfare, U.S. Highway 71’s narrow lanes and steep grades posed a problem for commercial trucks traveling through town. The road also cut through the business district, limiting growth and burdening in-city traffic. The solution? Reroute it to the east through Spout Spring.

Spout Spring was a neighborhood settled by formerly enslaved people and their descendants sometime after the Civil War. Encompassing a small valley with a spring-fed creek just east of what was then the Washington County Courthouse, the community core included East Meadow, Center, Mountain, and Rock Streets along with South Willow and Washington Avenues.(1) Its cornerstone institutions were the Mission School for Negroes Only (1866, renamed Henderson School in the 1890s), St. James Methodist Episcopal Church (1868), St. James Baptist Church (1885), and Lincoln Elementary School (1936), which replaced Henderson as the neighborhood school.

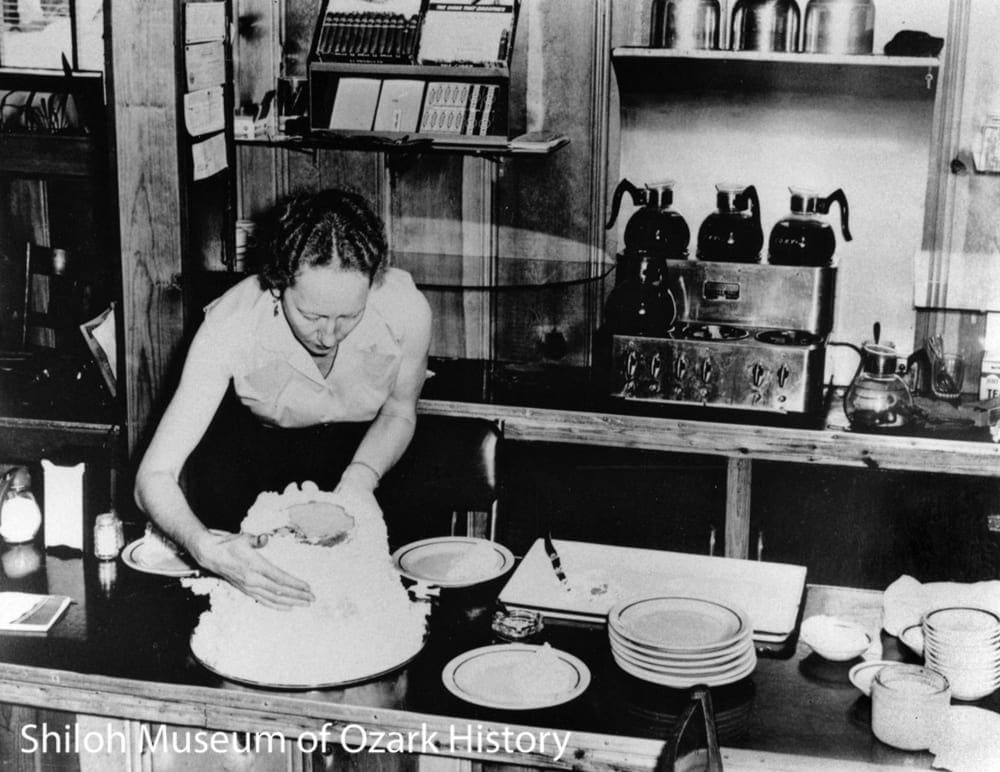

Susan Marshbank Manuel at her home on North Olive Avenue, Fayetteville, 1940s–early 1950s. “Mama Susie,” as she was known, offered accommodations for African-American travelers. Her home was listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book from 1939-1956.(2) Betty Hayes Davis Collection (S-2015-71-12)

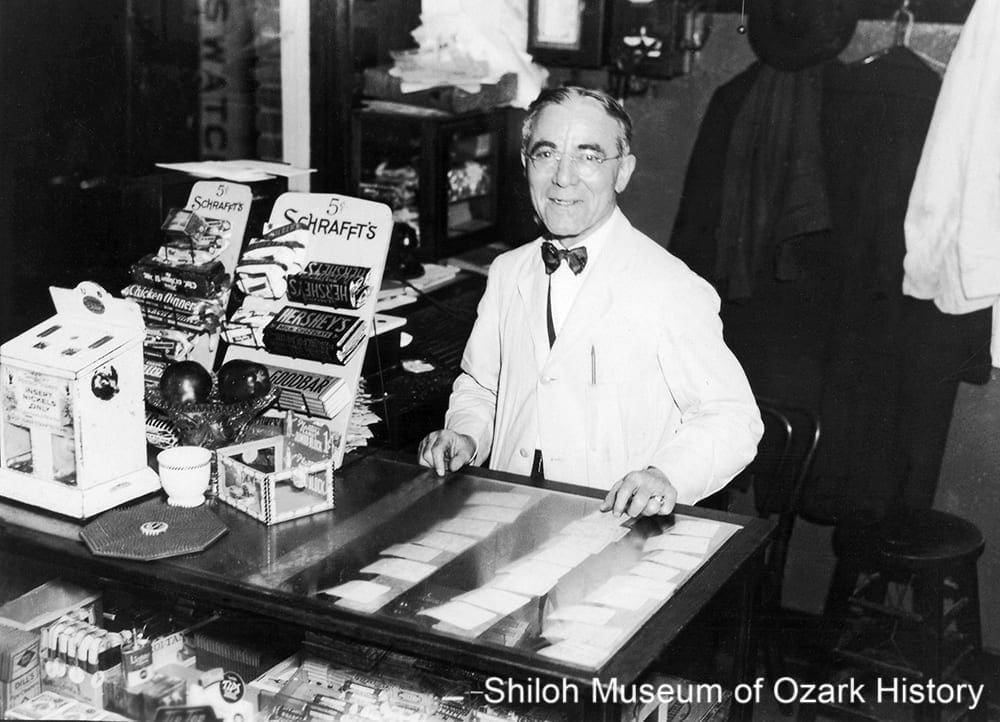

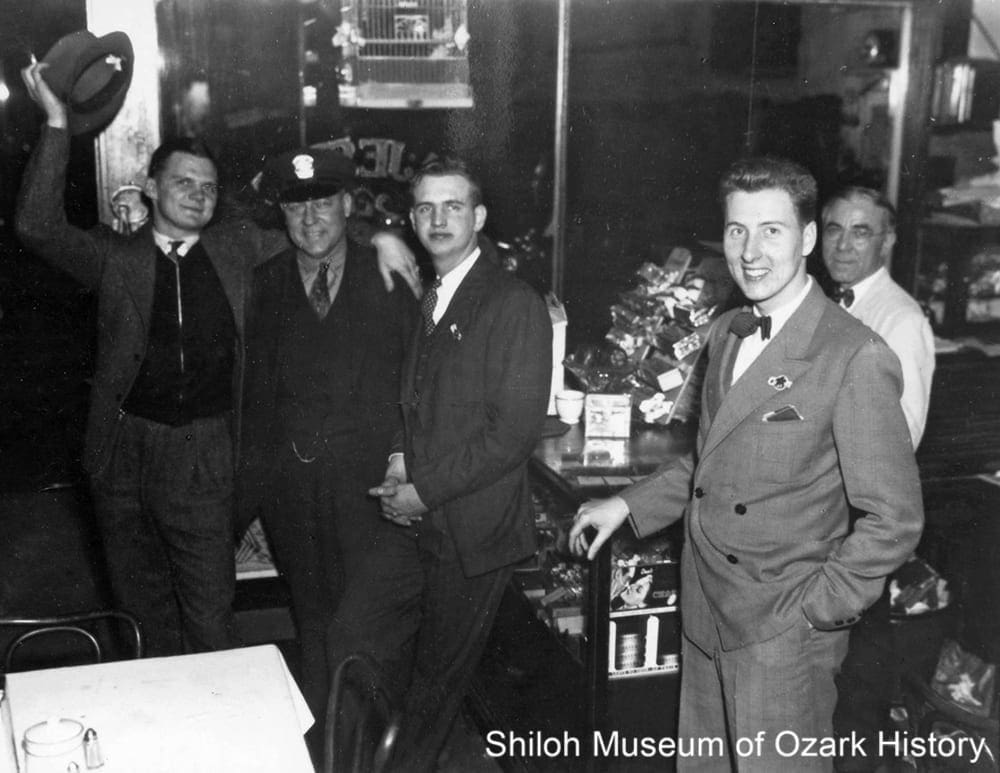

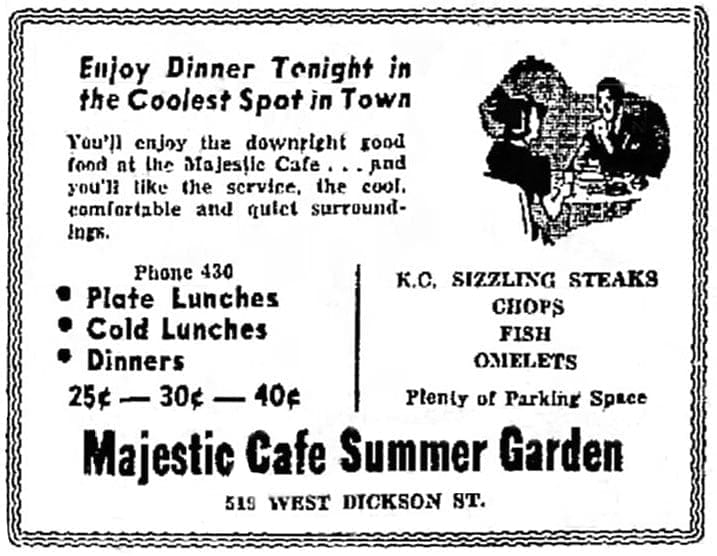

One of the first formerly enslaved African-Americans to purchase land near the core of Spout Springs was Tabitha Marshbank Taylor. In 1879 she bought a large lot on North Olive Avenue (3), which provided space for her and her descendants to build homes.(4) More folks bought property in the valley as early as the 1890s.(5) Many of Spout Spring’s residents worked as housekeepers, laborers, railroad porters, cooks, dishwashers, and shoe-shiners, in large part the only jobs that were open to them. Some operated small businesses out of their homes such as cafés, barbershops, and juke joints. Extra income was earned by renting rooms to travelling workers and, once it was integrated in 1948, University of Arkansas students. Because Fayetteville’s high school was for whites only, Black students seeking higher education were forced to move to larger Arkansas cities like Fort Smith and Pine Bluff or elsewhere to earn their diplomas.

High-school graduate Betty Hayes with her mother Clara Manuel Hayes in the yard of their home on North Olive Avenue, 1945. Betty lived in St. Louis with her uncle while attending Sumner High School. Also seen is the home of Tabitha Marshbank Taylor, Betty’s great grandmother, who bought the property in 1879. Betty Hayes Davis Collection (S-2015-71-50)

Spout Spring is identified as “Tin Cup” in the plan. According to Jessie B. Bryant, civic leader and founder of Northwest Arkansas Free Health and Dental Center, the name was used by white businessmen who stopped by the area for a cup of cool spring water and a quick bite of lunch. In a 2000 article in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette she said, “That’s the misconception of it all. It wasn’t part of the Black neighborhood. . . . if you mention ‘Tin Cup’ it’s automatically a derogatory term for the people in the community. But it had nothing to do with the community.”(6) University of Arkansas professor Dr. Gordon Morgan and his wife Dr. Izola Preston Morgan said much the same in a 1975 Northwest Arkansas Times article. “The Black community has never really considered itself as having a separate identity from that of Fayetteville at large. It has resisted such names as the Can, the Hollow, Tin Cup, and even East Fayetteville. These names have been given it by outsiders . . . who have had no practical knowledge of [the] history of the community.”(7)

Plate No. V depicts the proposed route change of U.S. Highway 71 through Fayetteville. A star has been added to mark the location of the Washington County Courthouse. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74)

Plate No. VII depicts a closeup of the route through the Spout Spring neighborhood, with proposed recreational parks and parking lot. A star has been added to mark the location of the Washington County Courthouse. Ann Wiggans Sugg Collection (S-2018-74)

The plan labeled Spout Spring as having sub-standard housing and deemed it a poor use of land. Because the area was considered a “natural beauty spot which should be preserved” and as “an area that will do much toward selling Fayetteville to the traveling public,” planners proposed rerouting Highway 71 east through Spout Spring. The adjacent land would be used to create two recreational parks and a parking lot for the use of citizens and travelers.

The suggestion was made to move the valley’s African-American residents to a federally funded, segregated “Negro Housing Project” just beyond the southeastern edge of town, in the belief that “when two races are mixed in a neighborhood all property loses value.” An adjacent ten-acre park centering on Wood Avenue would be developed “to serve the Negro population for recreation, school and church facilities.” Moving the city’s Black residents away from downtown meant that their new neighborhood would be “separate from areas of thickly settled white population” while being “close enough to the Business Section of the city as practical.” In other words, close enough for Blacks to continue to work for whites, but not so close as to impact their neighborhoods.

Government-sanctioned segregation was hardly a new idea. During the Great Depression of the 1930s the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure home mortgages in or near existing Black communities, considering the risk of falling property values too great. In urban areas, African Americans were pushed towards segregated housing projects which were often cut off from the rest of the city by major roads and highways.

This map depicts the locations of Spout Spring’s cornerstone institutions and the homes of some of the people pictured in this blog, contrasted against the proposed changes to the Spout Spring neighborhood and its relocation. A base map was drawn in 1936 by Fayetteville city engineer W. Carl Smith, which in turn was used as the base map for the various illustrations found in Six Year Public Works Program and Master City Plan, 1945. Neither map is to scale. Ada Lee Smith Shook Collection (S-97-60-35)

The authors seemed confident that the “Federal Government [would] undoubtedly furnish all or part of the money for many of these projects.” Following the plan’s publication Fayetteville moved ahead with several projects, largely using city funds with some federal money for planning. Land was purchased and plans were made to expand the hospital. A new water-pumping station was built and improvements made to water distribution lines and the sewer system. In need of housing for returning World War II veterans, land adjoining City Park (now known as Wilson Park) was secured for a short-term trailer village, and later used to expand the park.

But the rerouting of Highway 71 through Spout Spring never happened. A new proposal had emerged by 1947 to build an overhead viaduct between Rock and Third Streets to overcome the steep hill south of the courthouse. Mayor George T. Sanders believed it could be done “at much less expense than condemning and buying property elsewhere.”(8) Alternate routes were later proposed but ultimately the city couldn’t secure the funds to purchase the needed right-of-way.

Students with their teacher at Washington Elementary School, 1966-1967. Northwest Arkansas Times Collection (NWAT Box 15 66.413)

Spout Springs continued to be “a place where people live.” While the neighborhood remained largely segregated for several more decades, its people did not. Within days of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Fayetteville’s School Board unanimously voted to integrate its high school. They considered several factors—compliance with the ruling, a concerted push by Black and white community members, and the financial burden of paying for African-American high-school students to be educated elsewhere.(9) That fall seven Black students were welcomed in what was said to be a smooth, orderly fashion. Not that there weren’t difficulties throughout the year, but they were nothing like what befell the students who attempted to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. While Fayetteville’s junior high was integrated in 1955 it took another ten years before the school board integrated the elementary schools. In response to community petitions, the city’s movie theaters and the Wilson Park swimming pool were opened to Blacks in 1963. The following year Melvin E. Dowell was the first alumnus of Lincoln Elementary and Fayetteville High to receive a degree from the University of Arkansas.

FOOTNOTES

1. Information gleaned from the 1940 U.S. Census, based on race, house number, and street name.

2. Edmark, David. “Fayetteville in the Green Book: ‘A Knit Community.’” Flashback, Fall 2019.

3. Email from Tony Wappel, 10-5-2018.

4. Interviews with Betty Hayes Davis, 2012-2016.

5. Johnson, Eric. “Spout Spring in Memory and History.” Flashback, Spring 2017.

6. Schulte, Bret. “Jessie Ballie Carr Bryant: Helping the human race.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, 11-12-2000.

7. Morgan, Gordon and Izola Preston Morgan. “History Of Black Community Woven With City’s.” Northwest Arkansas Times, 7-16-1978.

8. Northwest Arkansas Times. “Rerouting of Highway 71 Up South College With Construction of Viaduct Proposed.” 4-15-1947.

9. Adams, Julianne Lewis and Thomas A. DeBlack. Civil Obedience: An Oral History of School Desegregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1954–1965. University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville: 1994.

Marie Demeroukas is the Shiloh Museum’s photo archivist/research librarian.