Rodeo Days

Rodeo Days

Online ExhibitSpringdale’s first rodeo was held in September 1926 at the local ball park. Two Oklahomans organized the event which featured twenty performers and various livestock. Cold weather led to a low turnout and the show lost money. People may also have stayed away because of their unfamiliarity with rodeo, described by the local newspaper as a “most unusual” type of entertainment.

The notion of holding another rodeo in Springdale started with Paul Bond and T. W. “Bill” Kelley, two Oklahoma construction workers who were in town on a remodeling job. The men, both rodeo promoters on the side, approached their boss, Walter Watkins of Welch’s Grape Juice Company, about staging a rodeo. Watkins passed the idea on to Thurman “Shorty” Parsons and Dempsey Letsch, owners of the Farmer’s Livestock Sales Barn on east Emma Avenue. With their support and that of the Clarence E. Beely American Legion post, the rodeo was on!

All of this happened in 1945 at the tail end of World War II, when patriotism was high and victory was in sight. The good folks of Springdale were ready to celebrate. It’s no wonder they chose the Independence Day holiday to stage the rodeo. Springdale had a long tradition of marking the Fourth of July with elaborate parades, picnics, races, ball games, band concerts, and speeches.

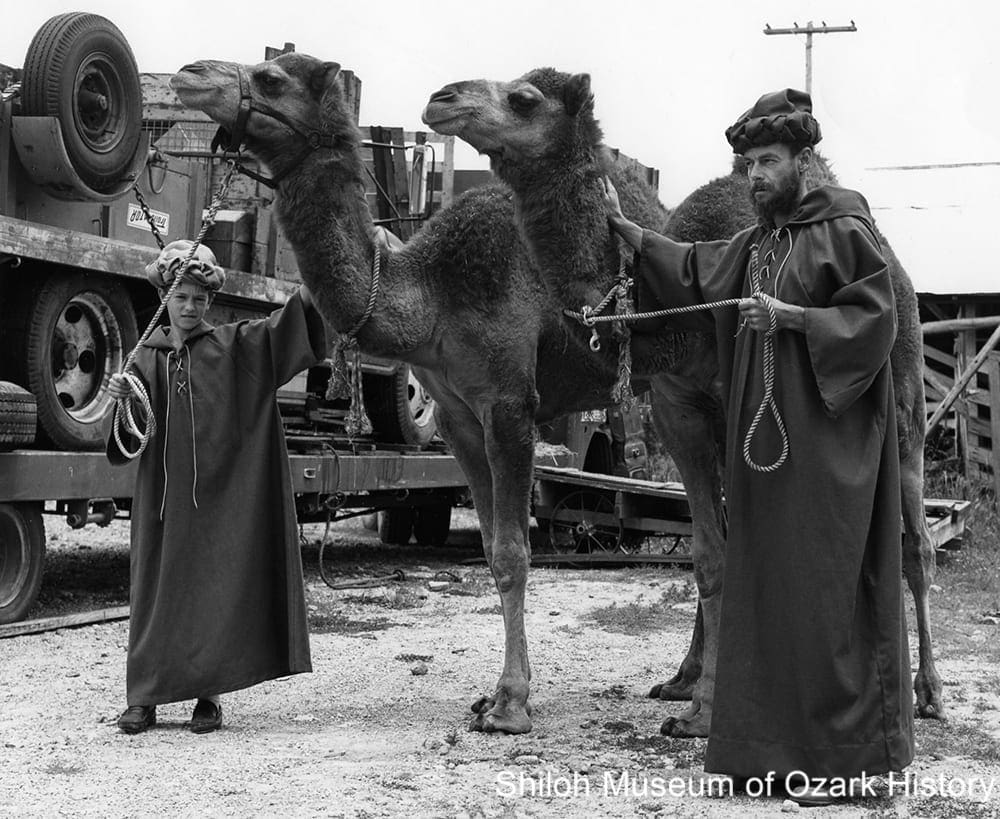

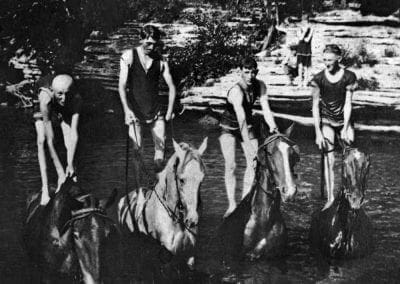

Organizers knew that they needed paying spectators in order to repay the loans necessary to bring lights, bleachers, performers, and stock to the empty lot next to Parsons and Letsch’s stockyard. Watkins organized a “goodwill caravan” to promote the rodeo. Members of the Springdale Riding Club and “Doc” Boone’s Skunk Holler Hillbilly Band hit the road, bringing horses, fancy riding gear, bluegrass, and comedy to the region’s towns. At each stop they’d perform music and boost the rodeo.

The promotion worked and tickets were sold for the three-day event. But on July 1 heavy rains fell and the rodeo’s first day was cancelled. Over the next two days good-sized crowds came to watch performers such as bronc stomper Sampson Sullivan of Oklahoma and local roper Glenn “Pup” Harp compete for $25 war bonds. Tragedy struck on the final night of the show. The wood bleachers collapsed, causing minor injuries to many spectators and severe injuries to a few. But despite bad weather and a terrible accident, the rodeo was a modest success.

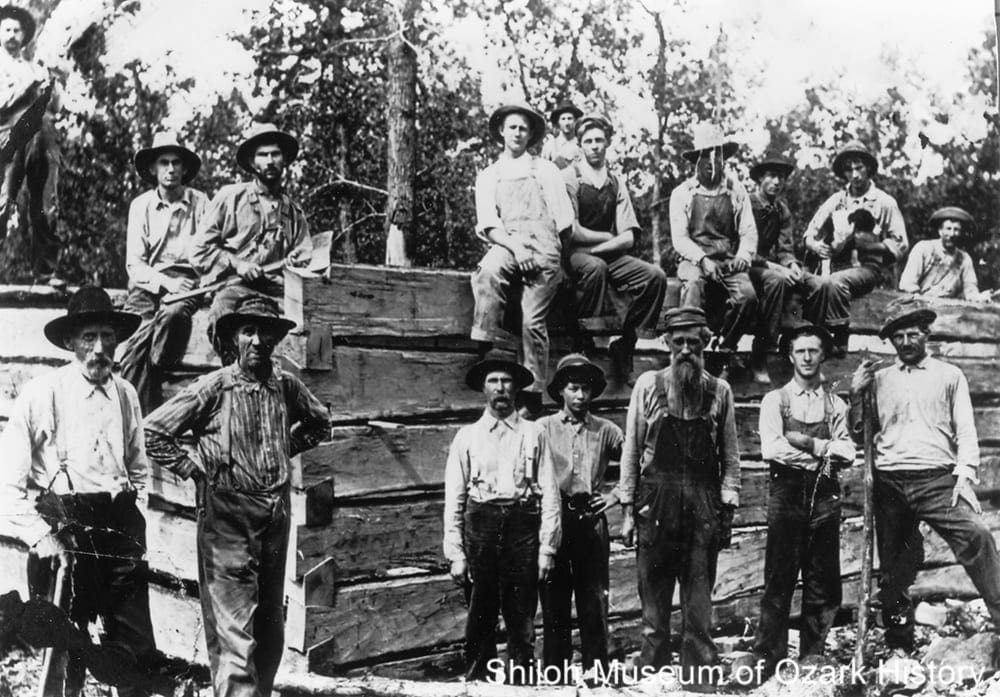

Improvements were necessary for the 1946 rodeo, now dubbed the “Rodeo of the Ozarks.” Sturdy, permanent bleachers were built and lights installed for nighttime performances. The Legion constructed box seats and the Chamber of Commerce provided financial support for advertising and prizes. Once again a rodeo caravan rode forth to spread the word. Best of all, the Rodeo Cowboys Association sanctioned the event, making it more desirable for performers to compete. The rodeo was a rousing success.

The following year the newly formed Springdale Benevolent Amusement Association bought the rodeo grounds and took over management of the rodeo. Over the years the rodeo has grown and attracted numerous visitors and top-quality performers to Parsons Stadium. These days cowboys and cowgirls compete for over $100,000 in prizes, crowds line Emma Avenue to watch the parades, and thousands of people make their way to Springdale to participate in the excitement and drama of the rodeo.

Rodeo’s Beginnings

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

After the Civil War cattle herds were increased to meet the demands of a growing country. Twice a year cowboys rounded up their free-ranging herds and drove them to market in Kansas City or Fort Worth, the end of the line for some railroads. After these long cattle drives cowboys held casual competitions to discover the best roper or rider.

By the late 1800s cattle drives were becoming a thing of the past. Barbed wire crisscrossed the range and ever-expanding railroads brought cattle cars to all points west. With the dwindling need for ranch hands and the homesteading of the plains, cowboys were at a loss on how to make a living. Enter Buffalo Bill Cody and the Wild West Show!

Designed to captivate and thrill audiences, the Wild West shows of the late 19th and early 20th centuries featured cowboys and Indians, bucking broncos, snorting bulls, and the like.The pageantry of the performers’ parade into the arena was followed by competitions of fancy riding, rope tricks, and other feats of showmanship.

During this time cowboys still held informal competitions at stock-horse shows and other venues, but now they performed in front of a paying audience. When Wild West shows fell victim to high production costs, cowboy competitions gained in popularity, often becoming the annual highlight of many a frontier town. Entry fees were added to prize purses, encouraging ropers and riders to compete for a little extra cash. As the sport grew, performers were able to earn a living on the rodeo circuit.

Rodeo soon professionalized itself. In 1929 the Rodeo Association of America was formed to set uniform competition rules. In the mid-1930s another organization was started by a group of cowboys angry about cheating rodeo promoters, poorly advertised shows, and unfair judging. Their efforts made a difference and the group became the Rodeo Cowboys Association in 1945. The modern era of rodeo had begun.

Springdale’s first rodeo was held in September 1926 at the local ball park. Two Oklahomans organized the event which featured twenty performers and various livestock. Cold weather led to a low turnout and the show lost money. People may also have stayed away because of their unfamiliarity with rodeo, described by the local newspaper as a “most unusual” type of entertainment.

The notion of holding another rodeo in Springdale started with Paul Bond and T. W. “Bill” Kelley, two Oklahoma construction workers who were in town on a remodeling job. The men, both rodeo promoters on the side, approached their boss, Walter Watkins of Welch’s Grape Juice Company, about staging a rodeo. Watkins passed the idea on to Thurman “Shorty” Parsons and Dempsey Letsch, owners of the Farmer’s Livestock Sales Barn on east Emma Avenue. With their support and that of the Clarence E. Beely American Legion post, the rodeo was on!

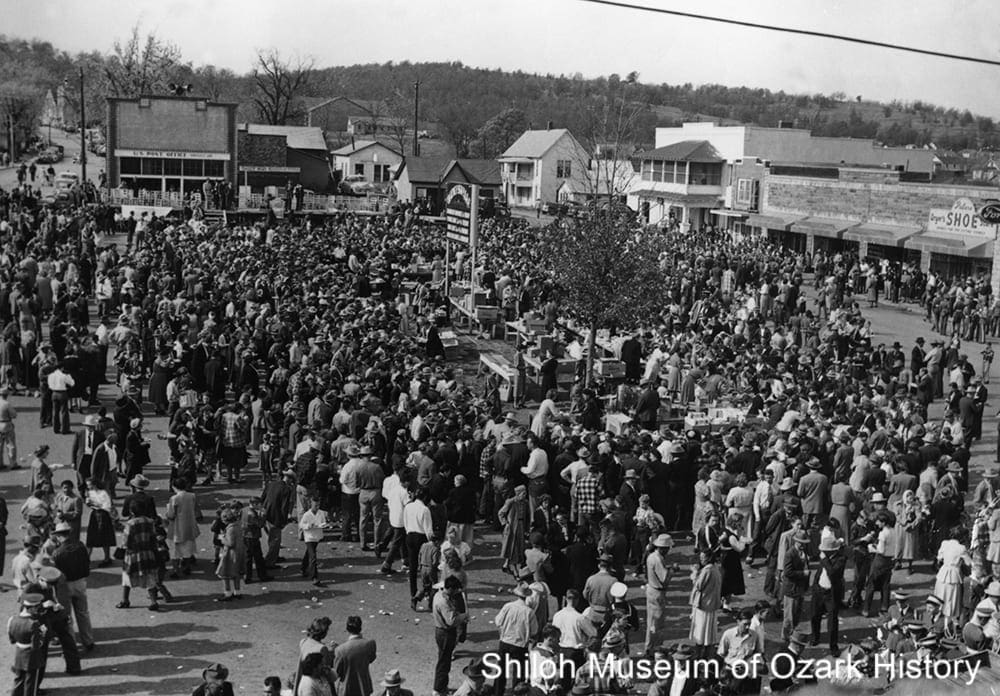

All of this happened in 1945 at the tail end of World War II, when patriotism was high and victory was in sight. The good folks of Springdale were ready to celebrate. It’s no wonder they chose the Independence Day holiday to stage the rodeo. Springdale had a long tradition of marking the Fourth of July with elaborate parades, picnics, races, ball games, band concerts, and speeches.

Organizers knew that they needed paying spectators in order to repay the loans necessary to bring lights, bleachers, performers, and stock to the empty lot next to Parsons and Letsch’s stockyard. Watkins organized a “goodwill caravan” to promote the rodeo. Members of the Springdale Riding Club and “Doc” Boone’s Skunk Holler Hillbilly Band hit the road, bringing horses, fancy riding gear, bluegrass, and comedy to the region’s towns. At each stop they’d perform music and boost the rodeo.

The promotion worked and tickets were sold for the three-day event. But on July 1 heavy rains fell and the rodeo’s first day was cancelled. Over the next two days good-sized crowds came to watch performers such as bronc stomper Sampson Sullivan of Oklahoma and local roper Glenn “Pup” Harp compete for $25 war bonds. Tragedy struck on the final night of the show. The wood bleachers collapsed, causing minor injuries to many spectators and severe injuries to a few. But despite bad weather and a terrible accident, the rodeo was a modest success.

Improvements were necessary for the 1946 rodeo, now dubbed the “Rodeo of the Ozarks.” Sturdy, permanent bleachers were built and lights installed for nighttime performances. The Legion constructed box seats and the Chamber of Commerce provided financial support for advertising and prizes. Once again a rodeo caravan rode forth to spread the word. Best of all, the Rodeo Cowboys Association sanctioned the event, making it more desirable for performers to compete. The rodeo was a rousing success.

The following year the newly formed Springdale Benevolent Amusement Association bought the rodeo grounds and took over management of the rodeo. Over the years the rodeo has grown and attracted numerous visitors and top-quality performers to Parsons Stadium. These days cowboys and cowgirls compete for over $100,000 in prizes, crowds line Emma Avenue to watch the parades, and thousands of people make their way to Springdale to participate in the excitement and drama of the rodeo.

Rodeo’s Beginnings

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

Rodeo’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1700s when Spanish missions dotted what eventually became the American West. Back then vaqueros, Spanish cattlemen, used such skills as riding, roping, branding, and herding in daily ranch life. As time went on these early cowboys’ style of dress, equipment, and ranching traditions were adopted and adapted by newcomers settling the open range.

After the Civil War cattle herds were increased to meet the demands of a growing country. Twice a year cowboys rounded up their free-ranging herds and drove them to market in Kansas City or Fort Worth, the end of the line for some railroads. After these long cattle drives cowboys held casual competitions to discover the best roper or rider.

By the late 1800s cattle drives were becoming a thing of the past. Barbed wire crisscrossed the range and ever-expanding railroads brought cattle cars to all points west. With the dwindling need for ranch hands and the homesteading of the plains, cowboys were at a loss on how to make a living. Enter Buffalo Bill Cody and the Wild West Show!

Designed to captivate and thrill audiences, the Wild West shows of the late 19th and early 20th centuries featured cowboys and Indians, bucking broncos, snorting bulls, and the like.The pageantry of the performers’ parade into the arena was followed by competitions of fancy riding, rope tricks, and other feats of showmanship.

During this time cowboys still held informal competitions at stock-horse shows and other venues, but now they performed in front of a paying audience. When Wild West shows fell victim to high production costs, cowboy competitions gained in popularity, often becoming the annual highlight of many a frontier town. Entry fees were added to prize purses, encouraging ropers and riders to compete for a little extra cash. As the sport grew, performers were able to earn a living on the rodeo circuit.

Rodeo soon professionalized itself. In 1929 the Rodeo Association of America was formed to set uniform competition rules. In the mid-1930s another organization was started by a group of cowboys angry about cheating rodeo promoters, poorly advertised shows, and unfair judging. Their efforts made a difference and the group became the Rodeo Cowboys Association in 1945. The modern era of rodeo had begun.

Fun Facts

- Although the days of the caravan are long over, Rodeo of the Ozarks board members travel to other rodeos to promote the event and invite cowboys and cowgirls to participate.

- In 1950 the Whisker Club was challenged by the men of Pea Ridge who, for some unknown reason, had begun growing beards weeks earlier. Springdale lost most of the beard-growing competitions (best groomed, most Abe-Lincoln-like), and were teased as “short beards.”

- Rodeo cowboys often wear big, flashy belt buckles. When the sport was first professionalized, many cowboys were also boxers and received similar belts as prizes in the ring.

- In 1946 Springdale’s citizens were asked to walk to the rodeo grounds or share a ride in an effort to keep parking spaces open for out-of-town visitors.

- The pointed toe in a cowboy boot makes it easy to regain a lost stirrup while a tall, tapered heel helps hold the boot in place. If a boot should get stuck in the stirrup during a wild ride, the loose top allows the cowboy to slip out of his boot and avoid injury.

- The phrase “cowboy up” means to face up to a difficult situation or challenge.

- The Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association was originally called the Cowboy Turtles Association. When they organized in 1936, these men fought cheating rodeo promoters, poorly advertised shows, and unfair judging. They said that although they were slow to band together, they had to stick their necks out for their beliefs.

- At one time fireworks were banned at the rodeo after they spooked the horses of the Springdale Riding Club, causing a stampede.

- “Biting the dust” happens when a rider is thrown from his horse. “Broomtail” is slang for a wild mare. When a bronc rider is “grabbin’ the apple,” he’s reaching for the pommel of his saddle to keep from being thrown from his horse.

- Bill Picket, an African-American cowboy who performed in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show in the late 1800s, is believed to have invented the sport of steer wrestling. His style of bulldogging included jumping from his horse onto the steer’s back, biting the animal’s lip, and twisting its horns until it fell to the ground. Today’s wrestlers don’t bite.

- The term “fishing” refers to a roper who has thrown at but missed an animal, but by chance the rope flips onto the animal’s neck.

- In 1948 Frank Autry was the Rodeo of the Ozark’s arena director. He was a cousin of movie star Gene Autry.

- A “honda” is the eye in the end of a rope through which the other rope end passes through, forming a loop.

- Bronc is short for bronco, which is Spanish for “rough” or “wild.”

- Fancy roping and trick riding were competitive events in early 1900s rodeos. Today they are paid performances.

- Each time a contestant wins a rodeo event, the prize money is tallied. A rodeo “champion” is the person who wins the most money for the year in one of seven sanctioned events at Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association-approved rodeos. The term “added money” refers to the total prize money in each event. It’s made up of the contestants’ entry fees and the purse put up by the rodeo. “Ground money” is split evenly among the contestants should no one win the event.

- In 1946 an 800-foot hitching rack was constructed at Parsons Stadium. That’s a lot of horses!

- The Professional Women’s Rodeo Association was established in 1987.

- The word “rodeo” is Spanish (pronounced ro-DAY-oh). It comes from the word rodear, meaning “to surround.”

1947 Rodeo of the Ozarks Parade

Photo Gallery

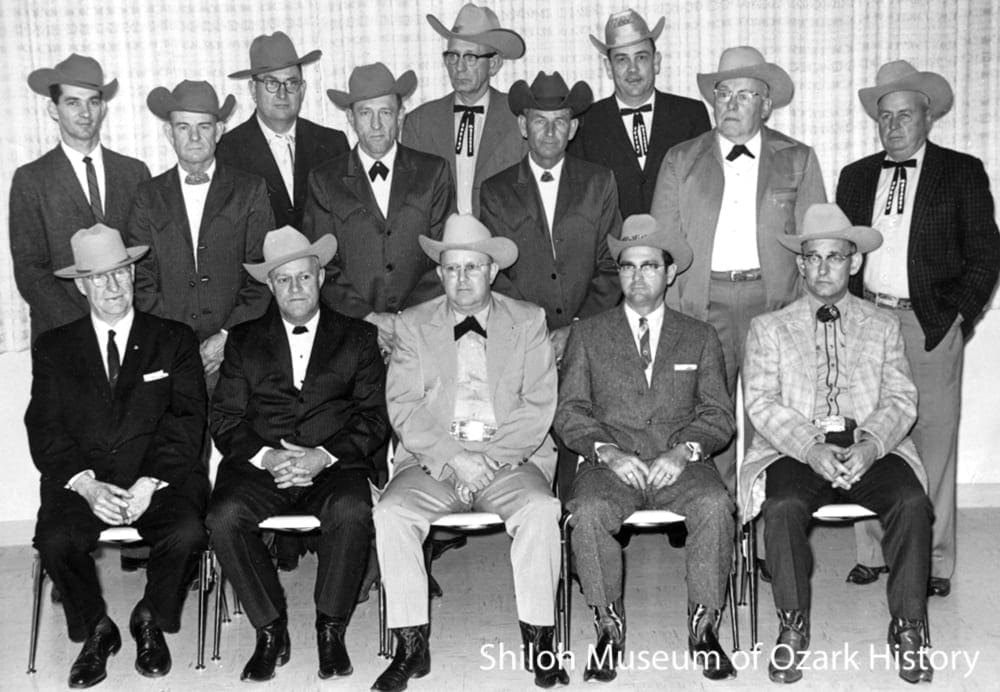

Rodeo Leaders

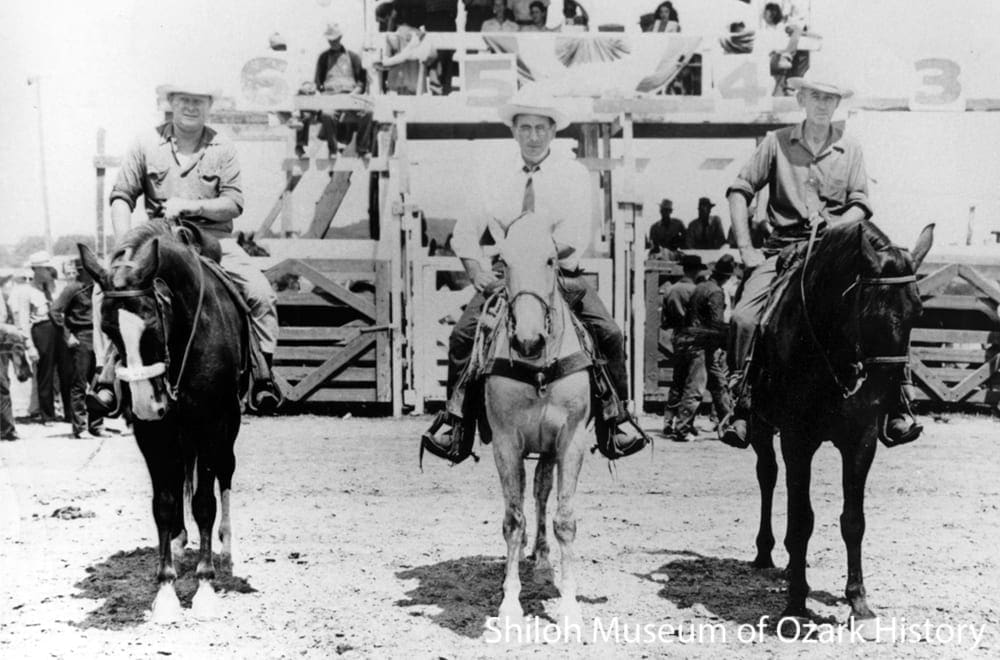

Early rodeo leaders, Parsons Stadium, Springdale, July 1946. From left: Walter Watkins, Evert Head, B. B. “Cap” Brogdon (1946 parade marshal). Springdale Chamber of Commerce Collection (S-84-157-69A)

Many noted Springdale residents and business leaders helped organize and operate the rodeo because “it was the thing to do.” The rodeo is part civic pride, part economic opportunity, and part good fun.

People like poultryman John Tyson, truckers Harvey Jones and Willis Shaw, grocer Don Harp, merchants Sandy Boone and Tex Holt, attorney Mace Howell, livestock men Shorty Parsons and Dempsey Letsch, and jeweler Mike Tatman have been among the many men and women who have contributed to the rodeo’s success.

Springdale Benevolent Amusement Association, 1963. Seated, from left: Ulysses A. Lovell, Wayne Hyden, Thurman “Shorty” Parsons, Joe Sanford “Sandy” Boone, Mace Howell. Standing, from left: Gene Thompson, Johnnie Gladden, Jerry E. Hinshaw, Howard Long, J.W. “Slim” Bayley, M. Hugh “Chick” Otwell, Wayne High, Don Hoyt, Otis Cardwell. Not pictured: Jay Martens. Ray Watson, photographer. Pat Parsons Hutter Collection (S-94-54-30)

In 1947 Shorty Parsons sold the rodeo grounds to the newly formed Springdale Benevolent Amusement Association. The Association raised funds in a number of ways, including $25 memberships. The stadium’s mortgage was paid off in 1954. Parsons served as president from 1950 to 1988.

Over the years the Association has used its proceeds for many local projects such as outfitting the Springdale High School band, developing a Babe Ruth baseball field, building a community center, and contributing to Ducks Unlimited and the Springdale National Guard Armory.

Early rodeo organizers, Shiloh Park, Springdale, 1949. Seated, from left: Velma Robinson, Murl Letsch, Gladys Reed. Back row, from left: Isabel Cloppert, Mrs. Calvin Walker, Patricia Parsons, Georgia Ritter (seated low on fence), unidentified, Marguerite Walker. Howard Clark, photographer. Howard Clark Collection (S-2002-72-2124)

In the early days, rodeo leaders and their wives took on many responsibilities to make the rodeo a success. Shorty Parsons and his family served brown beans, cornbread, and strawberry shortcake to 400 or so rodeo participants at the Parsons’ home.

Rodeo can get into a person’s blood. Parsons’ daughter, Pat Parsons Hutter, has been involved with the Rodeo of the Ozarks most of her life. She served as rodeo queen in 1950 and since 1958 has coordinated the queen’s pageant. She was a national barrel racer for forty-five years and even met her husband at the rodeo. She has never missed a parade or rodeo.

Promoting the Rodeo

Springdale’s Skunk Holler Hillbilly Band promoting the Rodeo of the Ozarks, Van Buren, Arkansas, June 1946. P. W. “Doc” Boone at the microphone, with Shelby Ford (in white hat). Don Hoyt Collection (S-86-315-39)

In the rodeo’s early days, goodwill caravans of horses, riders, and performers traveled miles and miles around Northwest Arkansas, eastern Oklahoma, and Southwest Missouri. The group put on short promotional shows. Their stage was a flat-bed trailer provided by Springdale produce broker Joe Robinson. In 1946 the caravan sold $16,000 in tickets.

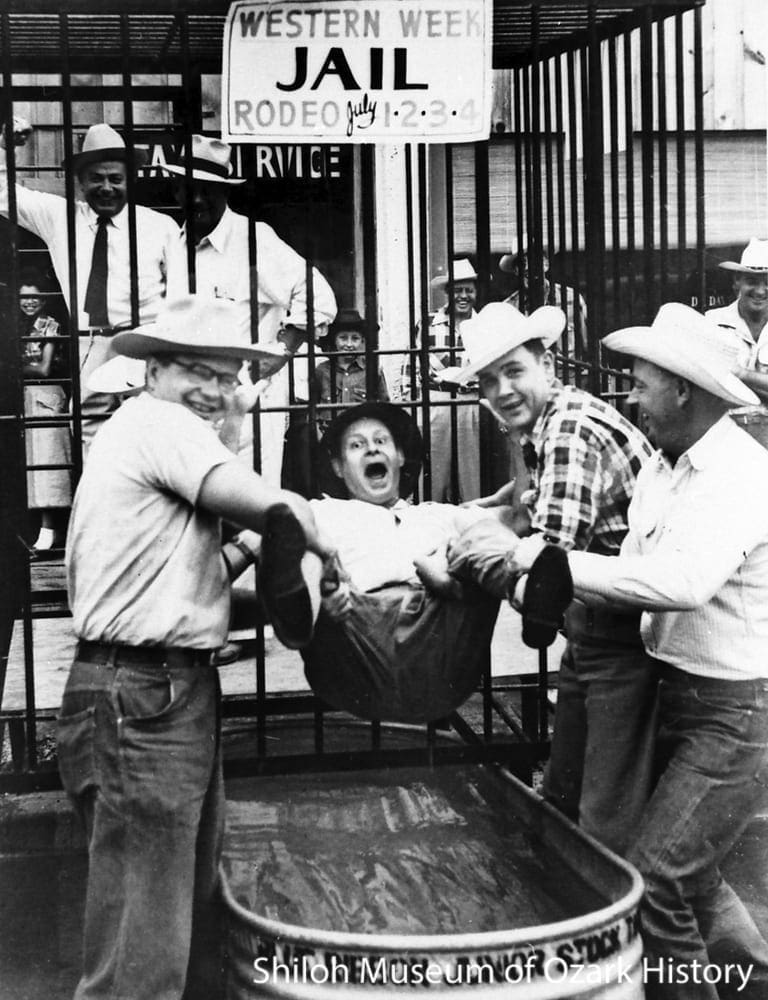

In June 1950 the caravan was ordered to “not block the streets” and “move on” in Noel, Missouri, prompting the Springdale Chamber of Commerce to declare that Noel would “not get another chance to disapprove of rodeo visitors.” A few days later two Noel businessmen came to town to be “punished” by a dunking in a stock tank full of water.

“Mac” McRoberts being dunked by Charles Tansey (left) and Wayne High, Emma Avenue, Springdale, 1952. Sandy Boone Collection (S-2006-154-18)

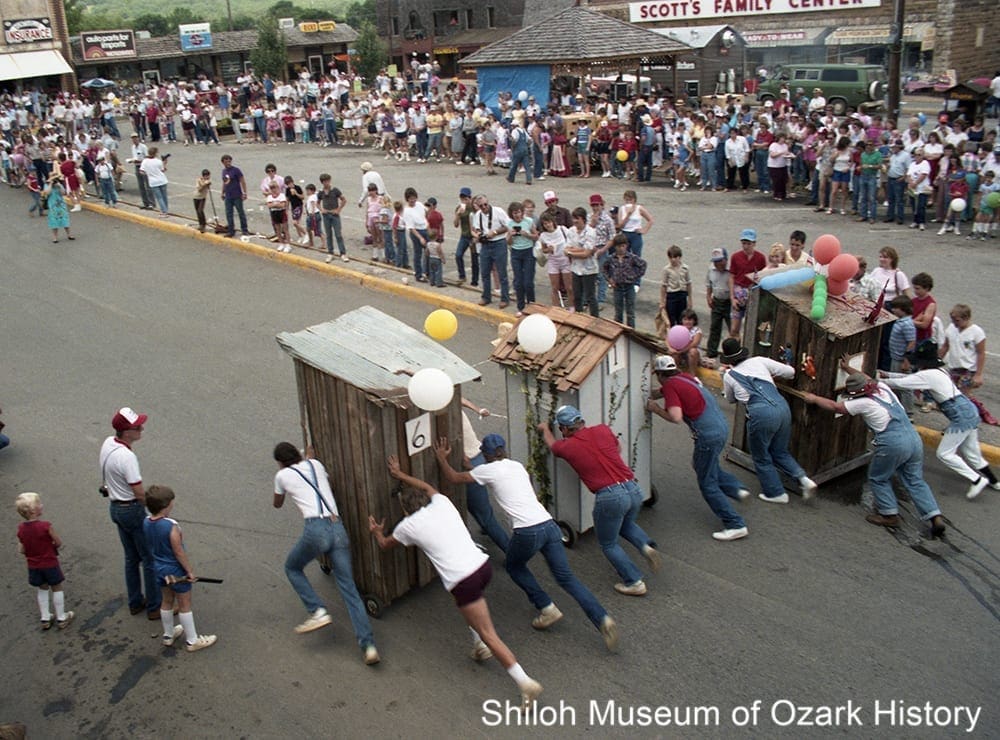

Springdale merchants decorated their businesses to promote rodeo spirit. During Western Week residents were asked to wear at least two pieces of western-style clothing. In 1950 the Whisker Club began and men were encouraged to grow beards. Those who didn’t could purchase shaving permits, with the proceeds going to rodeo festivities.

Folks who didn’t comply might be fined a small fee, dunked in a stock tank full of water, or tried by a “kangaroo court” and sent to “jail” until they were bailed out. In 1953 the guilty party might also have found himself the temporary caretaker of a “flap-eared burro.”

Parades

First Rodeo of the Ozarks parade, Emma Avenue, Springdale, July 1945. Evert and Reba Head (far left) lead the Springdale Riding Club. Sandy Boone Collection (S-2006-102-13)

Both Springdale and Fayetteville formed riding clubs in 1945. Springdale’s was Western in style while Fayetteville’s was Eastern and English—very traditional riding styles, saddles, and dress. Fayetteville’s club focused on proper horse breeding.

Fayetteville also held a horse event in 1945, but it wasn’t as well attended as Springdale’s rodeo. Some think that may have been due to the liveliness and informality of the rodeo appealing to a wide group of locals and country folks.

First National Bank’s second-place-winning float at the high school bus lot, Springdale, July 1949. From left: Georgia Mae Newton, Sarah Mitchell, Jean Kever, Mary Vaughan, Geraldine Kendrick, unidentified boy. Mary Maestri Vaughan Collection (S-99-33-6)

Hundreds of riders and their horses traveled down Emma Avenue during the first rodeo parades. Beginning in 1949 businesses and civic clubs entered floats with a western theme. Heekin Canning was famous for their “tin man” float, complete with a tin can cowboy dressed in western gear. Prizes were given for such things as best float, best dressed riding club, furthest traveled club, best large wagon and team, and best pony cart.

Rodeo of the Ozarks parade, Emma Avenue, Springdale, July 1967.

Springdale News Collection (SMN 7-1-4-67)

Each year Springdale holds two parades during the rodeo. Marching bands, stagecoaches, the Springdale Stepperettes, antique cars, riders and their horses, fire engines, rodeo officials and queens, civic groups, and even the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile have all traveled down Emma Avenue to the delight of the crowds.

Other rodeo festivities through the years have included square dance contests, barbecues, “shoot-outs,” horseshoe tournaments, pancake breakfasts, stick- horse parades, stagecoach rides, mare-colt races, chuck-wagon dinners, and “ole time mellodrammers.”

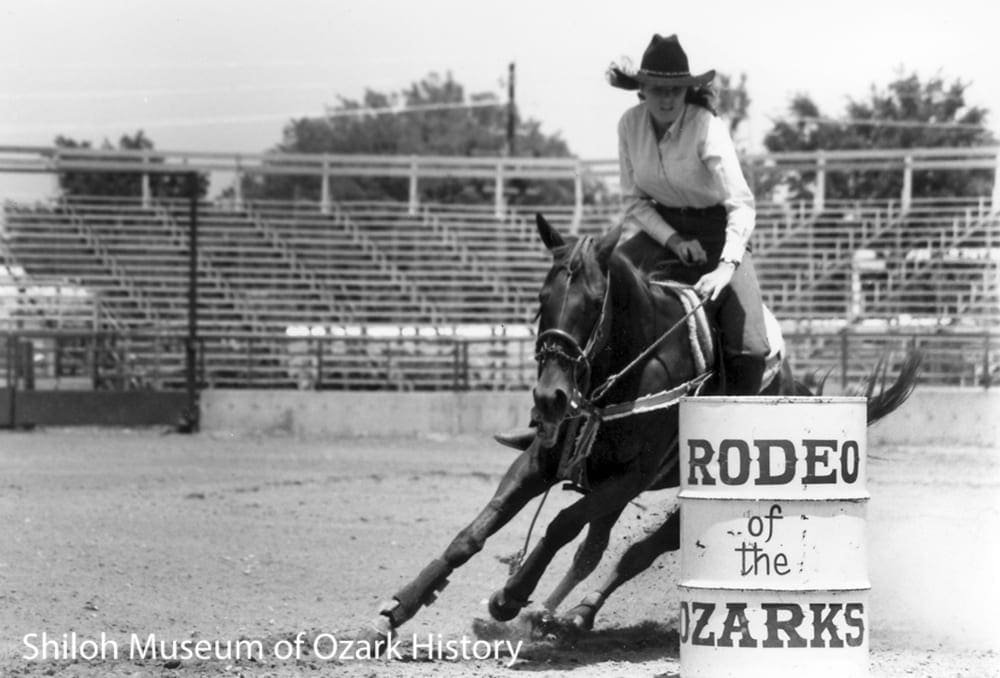

Women Rodeo Contestants

Kelli Martin of Siloam Springs, Ozarks Barrel Race Futurity-Derby, Parsons Stadium, Springdale, May 31,1985. Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 5-31-1985)

Women first competed in trick riding and bronc riding events at the 1897 rodeo in Cheyenne, Wyoming, but those days were short lived. Few competed in the early 1900s, when many thought a woman’s place was in the beauty pageant, not the rodeo arena. The tide changed in 1947 when an all-girl rodeo was staged in Amarillo, Texas. Its success proved that people would pay to watch female rodeo contestants.

Today barrel racing is a popular women’s sport. Riders and their quarter horses complete a quick cloverleaf pattern around three barrels. Penalties are given for each barrel tipped over. A good time is fourteen seconds.

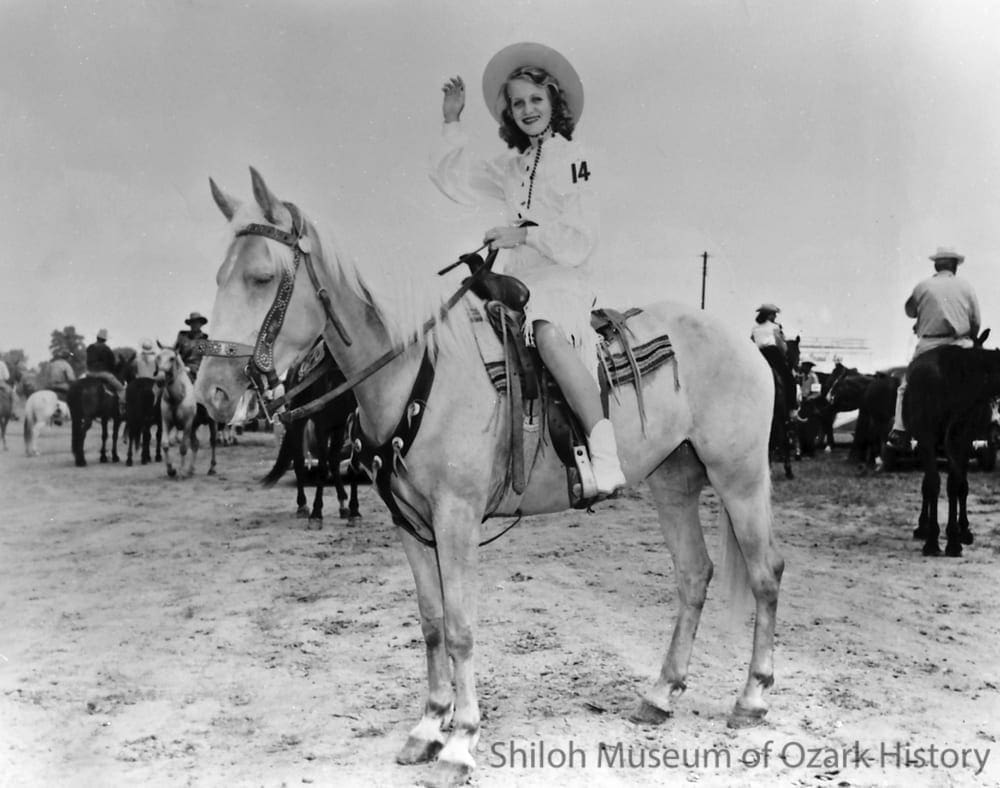

Sandra McWhorter of Rogers (Rodeo of the Ozarks queen candidate), Parsons Stadium, Springdale, July 1946. Hubert L. Musteen, photographer. Don Hoyt Collection (S-86-315-42A)

A rodeo queen’s duty is to promote the rodeo, give interviews, visit schools, and ride in parades. In 1993 candidates for queen were judged for their personality, appearance, and horsemanship. Each gave an impromptu speech about who they were, what their goals were, and what being Miss Rodeo of the Ozarks would mean to them.

The winner received roses, a crown, a custom saddle, and a photo session. The runner-up received a diamond watch while the horsemanship winner got a belt buckle and a pair of boots.

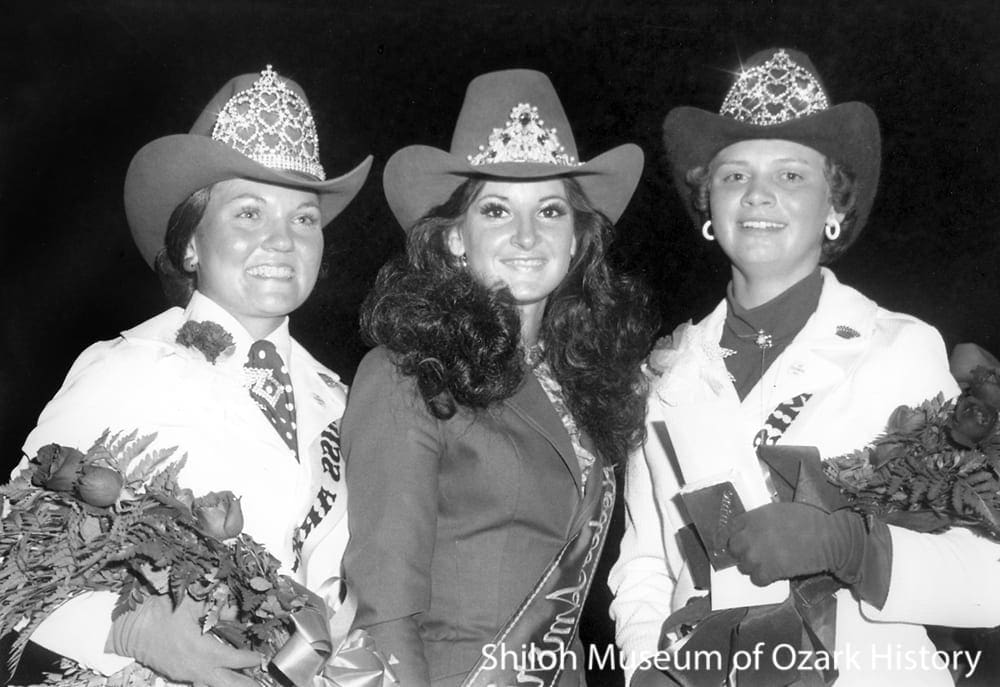

Rodeo queens, Parsons Stadium, Springdale, July 4, 1975. From left: Theresa King of Bentonville (Miss Rodeo of the Ozarks), Connie Della Lucia (Miss Rodeo America), and Debbie Garrett of Springdale (Miss Arkansas-Oklahoma Rodeo). Charles Bickford, photographer. Springdale News Collection (SN 7-4-1975)

Animal Rights

Animal-rights activists, Parsons Stadium, Springdale, July 4, 1992. Springdale News Collection (SN 7-4-1992)

The rodeo means many things to many people. To some it’s a time to have fun watching athletes test their skills against each other and their animals. To others it’s a time to worry about the treatment of animals in the chutes and the arena.

While all involved love animals and are concerned about their welfare, they don’t see eye to eye on the rights of animals or the sport of rodeo.

Credits

“15 Queens Sight for Sore Cowboy Eyes.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

“1,500 Welcome Tour Home; Program Stopped at Noel,” Springdale News, June 23, 1950.

“3,000 Witness Rodeo Parade Held Thursday,” Springdale News, July 11, 1946.

Boone, Joe Sanford “Sandy.” Interview by Kim Allen Scott, May 11, 1994.

“Chuck Wagon Feed Expected to Draw Big Crowd Tonight,” Springdale News, July 1, 1952.

Clark, Ralph. “Rodeo History.” About.com

“Complete Hitch Racks at Rodeo Grounds Tuesday,” Springdale News, June 6, 1946.

“Cousin of Gene Autry to Direct Springdale Rodeo.” Springdale News, June 28, 1948.

“Cowboy Garb is Dressy But it Has a Purpose,” Springdale News, June 29, 1959.

“Eighth Annual Show Features Varied Program,” Springdale News, July 2, 1952.

“First Annual Rodeo Draws Crowd,” Springdale News, July 5, 1947.

Haseloff, Cynthia. “Rodeo of the Ozarks Caravans Sold Tickets Around Region.” Northwest Arkansas Morning News, June 25, 2000.

“Hats, Boots Show Up,” Springdale News, June 22, 1953.

Litzinger, Beverly. “Local Entrepreneur a Rodeo Participant for More Than 50 Years.” Northwest Arkansas Times, June 30, 2000.

“Local Citizens Plan Purchase Rodeo Grounds,” Springdale News, 2-6-1947.

“Many Floats Will Be Featured in Rodeo Parade,” Springdale News, June 27, 1950.

Martinez, Diana Rowe. “The History of Rodeo.” 2000. suite101.com (web link no longer active as of February 2019).

“Miss Rodeo of the Ozarks on the Right Track.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

“Noel Men Dunked by Request in Apology for Tour Incident.” Springdale News, June 26, 1950.

“Parade Prize Winners Named.” Springdale News, May 5, 1949.

“Posses Looking for Fun, Ideas at World Famous Rodeos.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

Program. First Annual Fayetteville, Arkansas, Horse Show, June 1945.

Program. Rodeo of the Ozarks, July 1976.

“Quadrille Team Puts on Dandy Show.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

Rattenbury, Richard. “American Rodeo Gallery.” National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum website (web link no longer active as of February 2019).

Robson, Gary D. “Rodeo Terminology.” Caption Central. (web link no longer active as of February 2019).

“Rodeo of the Ozarks Action at 8 p.m. Wilder Than Shootout at High Noon.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

“Rodeo Dictionary.” Springdale News, June 28, 1948.

Scott, Kim Allen. “Let’s Rodeo! A Short History of the Rodeo of the Ozarks.” Unpublished manuscript, June 1995. Shiloh Museum research files.

“Springdale Benevolent Amusement As’sn Organized February 6, 1947.” Springdale News, June 28, 1948.

“Still in the Saddle: Parsons Family Keeps Riding with Rodeo of the Ozarks,” Northwest Arkansas Times, July 4, 2004.

Strong, Jean. “Rodeo of the Ozarks: Looking Ahead to 55 Years.” The Ketchpen, Spring 1999.

“Thousands Have Made Habit of Coming to City,” Springdale News, June 27, 1950.

“Trail Riders Drive Rodeo Spirit to Town.” Springdale News, June 20, 1993.

“Walk to Rodeo,” Springdale News, June 27, 1946.

“Welcome 7th Annual Rodeo of the Ozarks,” Springdale News, June 22, 1953.

Wells, Julie. “Women in Rodeo.” Women’s Professional Rodeo Association website (web link no longer active as of February 2019).

“Western Attire for all Residents Sought as Rodeo Time Nears,” Springdale News, June 13, 1951.

“Whisker Club Does Good Job of Advertising Local Rodeo,” Springdale News, June 27, 1950.

“Whiskers Club Funds to Provide Entertainment for Cowboys,” Springdale News, May 2, 1951.