Carnahan Cemetery, looking west toward Oklahoma.

NOTE: This is an update of a blog originally published in 2013.

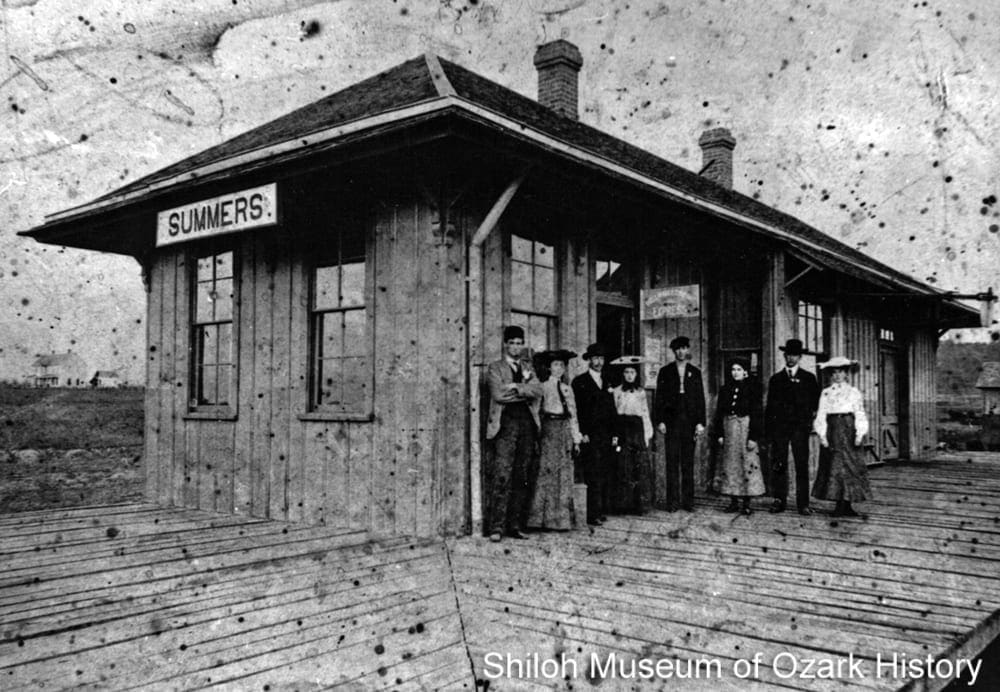

I recently participated in a driving tour of the west Washington County community of Cane Hill to get a sneak peek at preservation efforts being undertaken by the Historic Cane Hill organization. A highlight of the trip was a visit to Carnahan Cemetery, established with the burial of John Billingsley on Nov. 14, 1827. The old graveyard is high atop a windswept hill overlooking a lovely and expansive valley. To the west, seemingly just a stone’s throw away, is Oklahoma.

Immediately upon setting foot inside Carnahan Cemetery, I found myself transported back to 1837. On October 13 of that year, some 360 Cherokees led by Lt. B. B. Cannon left the Cherokee Agency in Tennessee bound for Indian Territory. They were going voluntarily as members of the “Treaty Party,” a small group of Cherokees who supported the Treaty of New Echota ceding all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River in exchange for $5 million and land in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Most Cherokees protested the Treaty of New Echota and refused to leave their ancestral homeland. This faceoff with the federal government resulted in the forced removal of thousands of Cherokees, a dark time in our history known as the Trail of Tears.

The Cannon detachment traveled overland through Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas on their trek to Indian Territory, arriving there December 27, 1837. Sickness and death accompanied them along every step of the ten-week journey. It is heartbreaking to read B. B. Cannon’s journal and his stark mentions of death along the way. Seventeen people lost their lives: fourteen children (including one “black boy”) and three adults.

For the Charles Timberlake family, the journey was horrific. Smoker Timberlake, age about eleven, was buried on December 17, 1837, after the detachment passed through Springfield, Missouri. Ten days later, on December 27, Smoker’s thirteen-year-old sister, Alsey, was buried somewhere near Cane Hill, Arkansas. The next day, December 28, another Timberlake child (whose name was unrecorded by Cannon) was buried in Indian Territory, most likely in the vicinity of present-day Stilwell, Oklahoma.

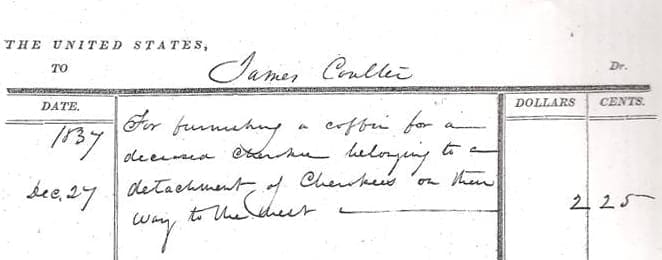

Receipt to James Coulter showing payment of $2.25 “for furnishing a coffin for a deceased Cherokee belonging to a detachment of Cherokees on their way to the west.” National Archives and Records Administration

A receipt discovered in the National Archives by members of the Oklahoma Chapter of the National Trail of Tears Association shows payment of $2.25 on December 27, 1837, to James Coulter of Cane Hill “for furnishing a coffin for a deceased Cherokee belonging to a detachment of Cherokees on their way to the west.” December 27, 1837—the day B. B. Cannon recorded the burial of Alsey Timberlake. The “deceased Cherokee” listed in the James Coulter receipt is thirteen-year-old Alsey Timberlake.

Land records show that James Coulter didn’t live too far from Carnahan Cemetery. Could this old burial ground be the final resting place of Alsey Timberlake? We’ll probably never know for sure. But I can tell you one thing for certain. On that day, in that place, high atop a hill looking west toward Oklahoma, Alsey Timberlake was right there with me.

Susan Young is the Shiloh Museum’s outreach coordinator.