Prehistoric Ozarks

Prehistoric Ozarks

Core Exhibit Indians first came to the Ozarks some 15,000 years ago, near the end of the Ice Age. They found a wet, cold climate and hills that were covered with spruce and pine trees. These prehistoric people did not settle down in one place, but instead roamed throughout the Ozarks pursuing big game animals like the mastodon and musk ox, as well as smaller game such as antelope and squirrel.

Indians first came to the Ozarks some 15,000 years ago, near the end of the Ice Age. They found a wet, cold climate and hills that were covered with spruce and pine trees. These prehistoric people did not settle down in one place, but instead roamed throughout the Ozarks pursuing big game animals like the mastodon and musk ox, as well as smaller game such as antelope and squirrel.

Over the next 2,000 years the climate in the Ozarks became warmer and drier. The large Ice Age animals became extinct, and the spruce and pine trees gave way to oak-hickory forests. These changes led to a new way of life for prehistoric Ozark Indians. The nomadic hunters settled down, and their diet began to include more plants, nuts, berries, and fish.

Diseases like smallpox and measles brought to America by Europeans may have led to the downfall of prehistoric Ozark Indians. By the time explorers and hunters made their way into Northwest Arkansas in the early 1800s, they found an area virtually uninhabited.

Indians first came to the Ozarks some 15,000 years ago, near the end of the Ice Age. They found a wet, cold climate and hills that were covered with spruce and pine trees. These prehistoric people did not settle down in one place, but instead roamed throughout the Ozarks pursuing big game animals like the mastodon and musk ox, as well as smaller game such as antelope and squirrel.

Over the next 2,000 years the climate in the Ozarks became warmer and drier. The large Ice Age animals became extinct, and the spruce and pine trees gave way to oak-hickory forests. These changes led to a new way of life for prehistoric Ozark Indians. The nomadic hunters settled down, and their diet began to include more plants, nuts, berries, and fish.

Diseases like smallpox and measles brought to America by Europeans may have led to the downfall of prehistoric Ozark Indians. By the time explorers and hunters made their way into Northwest Arkansas in the early 1800s, they found an area virtually uninhabited.

The early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They came in oxen-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a piece of land to call their own.

The early settlers were hardy, adventurous, and smart. They came in oxen-drawn wagons, bringing with them the things they needed to begin a new life. Tools, housewares, furniture, clothing and linens, livestock, seeds, and treasured heirlooms were carefully chosen. They knew how to clear land, grow crops, make and repair tools, preserve food, construct buildings, weave cloth, sew clothing, care for livestock, and doctor themselves. The work was hard, but the rewards were great—independence, a new beginning, and a piece of land to call their own. A settler’s first permanent shelter was often made of logs, such as the Lewis-Reed cabin (a portion of which is on exhibit). It was built in 1841 by Hugh Lewis in what was called “Boone’s Grove,” near present-day Elkins. Lewis came to Washington County from Missouri in 1831. By 1840, he and his wife Harriet had five children and 240 acres, including good bottom land for farming. The cabin changed hands twice more before it was bought by Alexander and Elizabeth Reed in 1866. Alexander was born in Tennessee and came to Northwest Arkansas in 1852. Elizabeth’s father William McGarrah came to Arkansas in 1826 from South Carolina and was one of Fayetteville’s first white settlers.

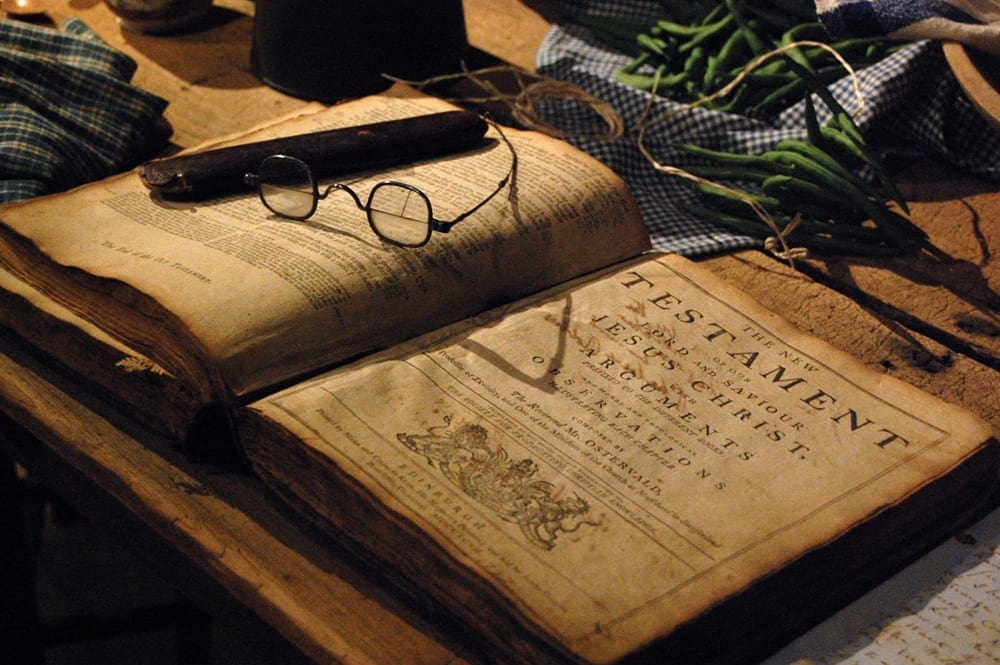

A settler’s first permanent shelter was often made of logs, such as the Lewis-Reed cabin (a portion of which is on exhibit). It was built in 1841 by Hugh Lewis in what was called “Boone’s Grove,” near present-day Elkins. Lewis came to Washington County from Missouri in 1831. By 1840, he and his wife Harriet had five children and 240 acres, including good bottom land for farming. The cabin changed hands twice more before it was bought by Alexander and Elizabeth Reed in 1866. Alexander was born in Tennessee and came to Northwest Arkansas in 1852. Elizabeth’s father William McGarrah came to Arkansas in 1826 from South Carolina and was one of Fayetteville’s first white settlers. There were no free, state-sponsored public schools in Arkansas until after the Civil War. While most children did not attend school, some were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic at home. There were a few short-term, fee-based schools scattered about, run by ministers or teachers (usually men, often with limited schooling themselves). For enslaved African Americans, education wasn’t illegal, but it wasn’t encouraged. Those few who were taught to read often learned their letters from the Bible, as a pathway towards Christianity. Well-to-do Cherokee and Choctaw families sent their children to be educated at the Fayetteville Female Seminary, along with the children of well-to-do whites. But the Indians faced prejudice, both from the community and from white parents, some of whom moved their girls to another school.

There were no free, state-sponsored public schools in Arkansas until after the Civil War. While most children did not attend school, some were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic at home. There were a few short-term, fee-based schools scattered about, run by ministers or teachers (usually men, often with limited schooling themselves). For enslaved African Americans, education wasn’t illegal, but it wasn’t encouraged. Those few who were taught to read often learned their letters from the Bible, as a pathway towards Christianity. Well-to-do Cherokee and Choctaw families sent their children to be educated at the Fayetteville Female Seminary, along with the children of well-to-do whites. But the Indians faced prejudice, both from the community and from white parents, some of whom moved their girls to another school.

By the 1870s and 1880s, the St. Louis-San Francisco (Frisco) Railway, having begun major railroad expansion, connected Missouri to Texas by going through Northwest Arkansas. The hardwood forests in the Ozarks and the labor of many men supplied more than 2,200 railroad ties per mile of track. Once rail lines were established in Northwest Arkansas, the trains were able to ship ties to other parts of the country. But the lumber industry also depleted the forests, leaving the land exposed and vulnerable to erosion.

By the 1870s and 1880s, the St. Louis-San Francisco (Frisco) Railway, having begun major railroad expansion, connected Missouri to Texas by going through Northwest Arkansas. The hardwood forests in the Ozarks and the labor of many men supplied more than 2,200 railroad ties per mile of track. Once rail lines were established in Northwest Arkansas, the trains were able to ship ties to other parts of the country. But the lumber industry also depleted the forests, leaving the land exposed and vulnerable to erosion. On April 6, 1917, after Germany had sunk three American ships, President Woodrow Wilson reluctantly issued a proclamation of war. Over 3,800 young men and women from Northwest Arkansas joined the armed forces between April 1917 and October 1918. At home, patriotism was high and most citizens supported the war. Almost every family was affected in some way by the war, so there was much rejoicing when the armistice (truce) ended the war at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918 and the “War to End All Wars” was over.

On April 6, 1917, after Germany had sunk three American ships, President Woodrow Wilson reluctantly issued a proclamation of war. Over 3,800 young men and women from Northwest Arkansas joined the armed forces between April 1917 and October 1918. At home, patriotism was high and most citizens supported the war. Almost every family was affected in some way by the war, so there was much rejoicing when the armistice (truce) ended the war at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918 and the “War to End All Wars” was over.

After World War II ended many people who had gone off to military service or to factory work in cities returned to Northwest Arkansas to take up their lives again. Soldiers who had seen their education interrupted returned to their studies at the University of Arkansas with tuition provided by the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly called the G. I. Bill.

After World War II ended many people who had gone off to military service or to factory work in cities returned to Northwest Arkansas to take up their lives again. Soldiers who had seen their education interrupted returned to their studies at the University of Arkansas with tuition provided by the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly called the G. I. Bill. When World War II veterans returned to Northwest Arkansas, the entire six-county region had a population of less than 140,000. Most people lived in small towns and rural communities. One in three had a high school education. Fruit and vegetable farming and canning factories were giving way to poultry houses and processing plants as the dominant industries.

When World War II veterans returned to Northwest Arkansas, the entire six-county region had a population of less than 140,000. Most people lived in small towns and rural communities. One in three had a high school education. Fruit and vegetable farming and canning factories were giving way to poultry houses and processing plants as the dominant industries.