Found, Then Lost

As a longtime employee of the museum I have driven various routes through Springdale on my way to work over the years. Occasionally I travel up (or down) North Commercial Street which fronts the west side of the train tracks between Emma and Johnson Avenues in downtown Springdale. A building there always caught my eye. It had such an unusual look about it that I wondered about its history.

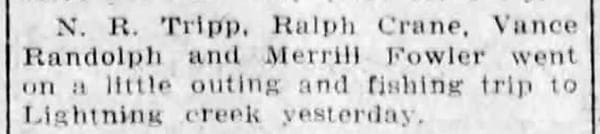

Well, a few weeks back I got my answer, and what fun! We were processing a scrapbook once kept by employees of Springdale’s old First National Bank and amongst the material on the bank’s history was tucked an undated Arkansas Gazette newspaper clipping: “State’s First ‘Stack-Sack’ Office Constructed for Springdale Lawyers.” (Research is leading me to believe the article ran sometime in November 1969.)

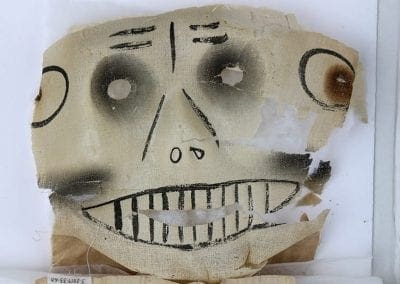

What’s that? A stack what? There in the article (with pictures) was the whole story about the building. Attorney and former Springdale mayor (1962–1966), Charles E. Davis and his partner, Joe B. Reed, decided to build a new office. They wanted something different, so they decided to use Stack-Sack construction, a new way of building walls made by filling burlap sacks with concrete, stacking them on rebar (steel rods), and then coating the exterior with masonry cement. The technique was developed by Edward T. Dicker, a Dallas builder, in 1966. By 1968 Dicker was selling licenses to contractors in the states and places like, Caracas, Venezuela, and the Pacific island of Saipan. He applied for patents in the United States and Russia and received approval from the Federal Housing Administration for FHA-insured financing. The building method had the advantage of being lower in cost and could be built in much less time than traditional construction.

In Springdale, Francis J. McCourt owned the Stack-Sack franchise for nine Northwest Arkansas counties, according to the news clipping. (McCourt, retired from the railroad and trucking business moved to Springdale about 1960, started a construction business about 1965, and developed two residential areas in town.) According to McCourt, Stack-Sack construction was “strong, fireproof, vermin-proof, sound-proof, and easy to maintain.” At the same time he was constructing the Davis-Reed law office, McCourt was also building a three-bedroom Stack-Sack home in Springdale.

I was so geeked to find the story of this building I shared it with staff and gave Marie Demeroukas, museum librarian, the original clipping for the research files. I kept a copy on my desk to remind me to do more research.

Then on Thursday, August 13, 2020, I was driving to work, heading west on Emma Avenue, and looked over to see Springdale’s Stack-Sack building—”the first ever built in Arkansas”—being demolished! After I put my jaw back in place I pulled over and took some pictures. I also grabbed a small chunk of concrete and burlap to take to the museum. I shared the news with Marie and she immediately suggested we needed a bigger example than the puny piece I had brought back. Aaron Loehndorf, museum collections specialist, overheard and volunteered to go get a bigger (and therefore heavier) relic. About that time museum photographer Bo Williams showed up and Marie asked him to go along and take pictures of remaining walls. So the three of us went over in the museum van. Bo took some great shots of the demolition and Aaron found some dandy examples of the burlap and concrete bags and stucco exterior, which are now resting on a cart in museum storage.

I came back to the museum and researched the Davis-Reed building. Old city directories revealed that Davis and Reed had an office on Mill Street until 1969. By 1970 they were installed in the Stack-Sack building on Commercial Street. Davis kept his law office there into the 1990s. The building was later owned by Jeff Watson, a Davis associate (and current Springdale City Council member). The last occupant was also a law firm. The property sold earlier this year to the same folks who bought the old Ryan’s Department Store and San José Manor buildings around the corner on Emma Avenue.

Downtown Springdale is seeing lots of changes and plans are afoot for development. I guess the old Stack-Sack building, once the first of its kind, had to give way for the future.

Here’s a link to a pdf of the original Arkansas Gazette news clipping found in the First National Bank scrapbook that set this research project in motion. Courtesy Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Here’s a link to a story about the Stack-Sack technique featured in Concrete Construction magazine, March 1971.

Postscript: The site of the former David-Reed building is now a tidy flat lot awaiting development. Francis J. McCourt sold his properties and moved out of state in the 1970s. His Stack-Sack house still stands in Springdale.

Carolyn Reno is the Shiloh Museum’s assistant director/collections manager.