Norwood School (Benton County, Arkansas), 2015. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

My first major research project for the Shiloh Museum was in preparation of a New Deal photo exhibit set to open in December 2015. In a discussion about the exhibit, it was casually mentioned that the New Deal included the construction of outhouses. It then became a challenge for me to locate these elusive creations.

In search of a listing of New Deal projects completed in our six-county focus area (Benton, Boone, Carroll, Madison, Newton, and Washington counties), I scoured crumbling newspapers, faded and blurred microfilm, various tomes on archaeological research of state and national parks, websites for the National Health Services, local histories, and the National Register of Historic Places. Imagine my delight when I found an article listing 505 sanitary units constructed in Washington County alone. No, you did not misread that: 505! But that was just a mention of them; not an actual listing of their locations. Still, I was not deterred. The hunt was on!

Allow me to set the stage with a little background on the Depression and the New Deal in Arkansas. In 1927, a great flood devastated much of Arkansas when the Mississippi burst its banks and caused other rivers like the Arkansas, White, and St. Francis to overflow as well. The Red Cross provided relief to those impacted by the months-long flooding. The flood was followed three short years later by a drought. While Arkansas may not have been as impacted by the stock market crash of 1929 as other states, its residents were in dire need when Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in 1933. A testimony to this can be found in the 1935 and 1936 editions of the Springdale News, which list pages and pages of folks so strapped for money that they were delinquent in paying their taxes.

Government relief was by no means a novel concept when Roosevelt took office. His predecessor, Herbert Hoover, had begun his own relief programs with limited success. Whether or not these measures would have been successful in the long run is unknown, because Hoover was not voted in for a second term.

Under Roosevelt’s New Deal, relief efforts were expanded (many of the programs were precursors to contemporary programs). He established a sort of alphabet soup of agencies like the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the WPA (Works Progress Administration/ Works Project Administration), the AAA (Agricultural Adjustment Administration), FERA (Federal Emergency Relief Administration) and many others. The Social Security Administration was born, as well as reforms and regulatory groups intended to prevent future catastrophic failures. I won’t bore you with the details or the hierarchies, but if you want more information, check out Living New Deal.

Arkansas received more aid per capita than many other states because Arkansas did not generate enough revenue to pull itself out of the mire. (For a state-by-state comparison, see the 1941 report on the WPA.) Arkansas had an agricultural base, but with plummeting prices for crops, there was no way to earn enough to support the state’s families.

Most New Deal programs focused on education and infrastructure. In Arkansas, FERA provided over $600,000 in funds for teacher salaries and schools. FERA also provided access to commodities. Distribution of these commodities led to the need for better roads for deliveries and commissaries where recipients could pick up their supplies. The WPA, NYA (National Youth Administration) and CCC built water towers, post offices, schools, roads, campgrounds, state and municipal parks, dams, canning kitchens, jails and courthouses. Some of these projects were new construction and some were extensive repairs.

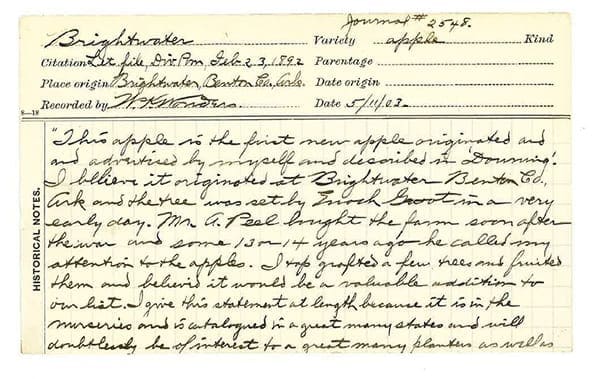

Now, back to my research. As of yet I have been unable to locate an exhaustive list of projects completed under the New Deal, so I have begun compiling my own list. (I am currently up to 151 projects that were certainly or likely completed under the New Deal in our six-county region, and I welcome any additions or corrections.) Once my list reached the one hundred mark, I began researching outhouses—or rather, sanitary privies and sanitary units—in earnest, even though I had found only one miserly mention of outhouses among the Northwest Arkansas New Deal projects.

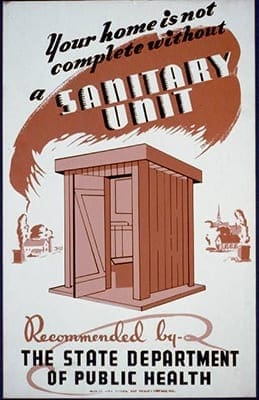

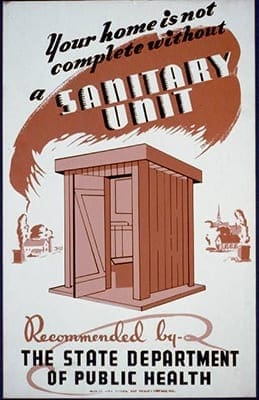

Did you know that there are government publications on the very subject of outhouses? In 1943, E.S. Tisdale, the Sanitary Engineer for the Public Health Service, along with C.H. Atkins, the assistant engineer, published The Sanitary Privy and its Relation to Public Health. Even better is the U.S. Treasury Department and Public Health Service bulletin, The Sanitary Privy, published in the 1930s. This document focuses on the types of outhouses, the pit types, bench types and even a suggested example of text for city ordinances. There are even posters and advertisements to promote the use of these structures.

WPA Poster Collection, Library of Congress

Between 1933 and 1942 over two million sanitary privies were constructed and over 110 million dollars was spent on this effort in the United States. Arkansas had 53,808 sanitary units constructed within its boundaries. And remember, Washington County, Arkansas had 505. I finally stumbled across a mention in the local newspapers of WPA outhouses in Boxley (Newton County). Unfortunately, my hopes were momentarily dashed when I could not find information about whether or not those outhouses were still in existence. I returned to the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program’s list of historic structures with outhouses in the back of my mind. I was, after all, still compiling a list of WPA construction projects. There I stumbled upon a little gem of information buried in the site description of the National Register nomination for Norwood School in Benton County: a “stone ‘outhouse’ with metal roof, contemporary to the school building, is still on the premises.'”

Still, I did not get my hopes up. It was entirely possible that the outhouse had suffered an untimely demise since the building’s nomination in the 1980s. So one evening I set off along the back roads southeast of Siloam Springs. I had grown up in this part of the world on a dairy farm only a few miles away. How had I not known about this hidden piece of history? Alas, online mapping sent me down and around to Nicodemus community instead of my destination. But I had made it this far. I was not going to give up. At last, I arrived late in the evening at my destination—Norwood School. As I parked in front of the old schoolhouse, I noticed a smaller stone structure, mostly obscured by an old tree. Cue the choir! I had found one! Finally, a New Deal outhouse!

Norwood School’s circa 1937 girls outhouse, 2015.

She was made of rougher stone than the school, more like she was thrown together from leftover pieces of the school building. A squat companion to the school for the past seventy-eight years, with a hidden opening and pieces of metal bent and slapped jauntily on top, she had stood up to the vines trying to erode her joints and also to the lack of a proper foundation. And the thrills just kept coming. I was surprised to discover that not only had one outhouse survived, but two!

The current owner of the property was kind enough to share what information he had on the school and the outhouses. The school was used as a church during the late 1970s or early 1980s, and the privies were used by the congregation. The girls privy (seen above), has since had the holes (not a single hole unit, this!) boarded over to deter pranksters and unwanted pests. It is located to the left of the school building, camouflaged from the most casual of observers. The other structure, the boys outhouse, sits somewhere to the right, hidden from view. It has been converted into a well-house.

With the use of this now-archaic structure, we moved past the diseases and germs prevalent in previous generations. Likewise, the education programs that accompanied the construction of these humble outbuildings brought a growing awareness of how disposal contaminated water supplies and food. Equally important, the construction of outhouses created jobs through programs like the WPA, CCC and CWA. We laugh now and poke fun at her, but in reality, the outhouse was an important part of the New Deal—after all, they built over two million of them.

I pulled away from Norwood School, exhilarated by my find. Indiana Jones I was not, but I had rediscovered that elusive artifact of civilization, the New Deal outhouse.

Like a kid in a candy store, I look forward to my next research project and what extraordinary ephemera I might discover along the way.

Rachel Whitaker is the Shiloh Museum’s research specialist.